History of the Left in France

Encyclopedia

The Left in France at the beginning of the 20th century was represented by two main political parties

, the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party and the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), created in 1905 as a merger of various Marxist parties. But in 1914, after the assassination of the leader of the SFIO, Jean Jaurès

, who had upheld an internationalist

and anti-militarist line, the SFIO accepted to join the Union Sacrée national front. In the aftermaths of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the Spartacist

insurrection in Germany

, the French Left divided itself in reformists and revolutionaries during the 1920 Tours Congress

, which saw the majority of the SFIO spin-out to form the French Section of the Communist International

(SFIC).

The distinction between left and right wings in politics derives from the seating arrangements which began during the Assemblee Nationale in 1789 (The more radical Jacobin or Montagnard deputies sat on the upper left benches). Throughout the 19th century, the main line dividing Left and Right in France

The distinction between left and right wings in politics derives from the seating arrangements which began during the Assemblee Nationale in 1789 (The more radical Jacobin or Montagnard deputies sat on the upper left benches). Throughout the 19th century, the main line dividing Left and Right in France

was between supporters of the Republic and those of the Monarchy. On the right, the Legitimists held counter-revolutionary views and rejected any compromise with modern ideologies while the Orleanist

s hoped to create a constitutional monarchy

, under their preferred branch of the royal family, a brief reality after the 1830 July Revolution

. The Republic itself, or, as it was called by Radical Republicans

, the Democratic and Social Republic (la République démocratique et sociale), was the objective of the French workers' movement, and the lowest common denominator

of the French Left. The June Days Uprising

during the Second Republic

was the attempt by the left to assert itself after the 1848 Revolution, that foundered on its own divided radicalism which too few of the (still predominantly rural) population shared.

Following Napoleon III's 1851 coup

and the subsequent establishment of the Second Empire

, the Left was excluded from the political arena and focused on organising the workers. The growing French workers movement consisted of diverse strands; Marxism

began to rival Radical Republicanism and the "utopian socialism

" of Auguste Comte and Charles Fourier with whom Karl Marx

had become disillusioned. Socialism fused with the jacobin ideals of Radical Republicanism leading to a unique political posture embracing nationalism, socialist measures, democracy and anti-clericalism

(opposition to the role of the church in controlling French social and cultural life) all of which remain distinctive features of the French Left. Most practicing Catholics continue to vote conservative while areas which were receptive to the revolution in 1789 continue to vote socialist.

was throughout the 19th century the permanent theater of insurrectionary movements and headquarters of European revolutionaries. Following the French Revolution

of 1789 and the First French Empire

, the former royal family returned to power in the Bourbon Restoration

. The Restoration was dominated by the Counter-revolutionaries who refused all inheritance of the Revolution and aimed at re-establishing the divine right of kings

. The White Terror

struck the Left, while the ultra-royalist

s tried to bypass their king on his right. This intransigeance of the Legitimist monarchists, however, finally led to Charles X's downfall during the Three Glorious Days, or July Revolution

of 1830. The House of Orléans

, cadet branch of the Bourbon, then came to power with Louis-Philippe, marking the new influence of the second, important right-wing tradition of France (according to the historian René Rémond

's famous classification), the Orleanist

s. More liberal

than the aristocratic supporters of the Bourbon, the Orleanists aimed at achieving a form of national reconciliation, symbolized by Louis-Philippe's famous statement in January 1831: "We will attempt to remain in a juste milieu (the just middle), in an equal distance from the excesses of popular power and the abuses of royal power."

and of census suffrage, the right-wing opposition to the regime (the Legitimists) and the left-wing opposition (the Republicans

and Socialists). The loyalists were divided into two parties, the conservative, center-right, Parti de la résistance (Party of the Resistance), and the reformist center-left Parti du mouvement (Party of the Movement). Republicans and Socialists, who requested social and political reforms, including universal suffrage

and the "right to work

" (droit du travail), were then at the far-left of the political board. The Parti du mouvement supported the "nationalities

" in Europe, which were trying, all over of Europe, to shake the grip of the various Empires in order to create nation-states. Its mouthpiece was Le National. The center-right was conservative and supported peace with European monarchs, and had as mouthpiece Le Journal des débats.

The only social law of the bourgeois July Monarchy was been to outlaw, in 1841, labor to children

under eight years of age, and night labor for those of less than 13 years. The law, however, was almost never implemented. Christians imagined a "charitable economy", while the ideas of Socialism, in particular Utopian Socialism

(Saint-Simon

, Charles Fourier

, etc.) diffused themselves. Blanqui

theorized Socialist coup d'états, the socialist and anarchist

thinker Proudhon theorized mutualism, while Karl Marx

arrived in Paris in 1843, and met there Friedrich Engels

.

Marx had come to Paris to work with Arnold Ruge

, another revolutionary from Germany, on the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, while Engels had come especially to meet Marx. There, he showed him his work, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844

. Marx wrote for the Vorwärts

revolutionary newspaper, established and run by the secret society called League of the Just, founded by German workers in Paris in 1836 and inspired by the revolutionary Gracchus Babeuf and his ideal of social equality

. The League of the Just was a splinter group from the League of Outlaws (Bund der Geaechteten) created in Paris two years before by Theodore Schuster

, Wilhelm Weitling

and others German emigrants, mostly journeymen. Schusterr was inspired by the works of Philippe Buonarroti

. The latter league had a pyramidal structure inspired by the secret society

of the Republican Carbonari

, and shared ideas with Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier

's utopian socialism. Their aim was to establish a "Social Republic" in the German states which would respect "freedom", "equality" and "civic virtue".

The League of the Just participated in the Blanquist

The League of the Just participated in the Blanquist

uprising of May 1839 in Paris. Hereafter expelled from France, the League of the Just moved to London, where they would transform themselves into the Communist League

.

In his spare time, Marx studied Proudhon, whom he would later criticize in The Poverty of Philosophy

(1847). He developed his theory of alienation

in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

, published posthumously, as well as his theory of ideology

in The German Ideology

(1845), in which he criticized the Young Hegelians

: "It has not occurred to any one of these philosophers to inquire into the connection of German philosophy

with German reality, the relation of their criticism to their own material surroundings.". For the first time, Marx related history of ideas with economic history, linking the "ideological superstructure" with the "economical infrastructure", and thus tying together philosophy and economics. Inspired both by Friedrich Hegel and Adam Smith

, he imagined an original theory based on the key Marxist notion of class struggle

, which appeared to him self-evident in the Parisian context of insurrection and permanent turmoil. "The dominant ideology is the ideology of the dominant class," did he conclude in his essay, setting up the program for the years to come, a program which would be further explicated in The Communist Manifesto

, published on 21 February 1848, as the manifesto of the Communist League, three days before the proclamation of the Second Republic. Arrested and expelled to Belgium, Marx was then invited by the new regime back to Paris, where he was able to witness the June Days Uprising

first hand.

(1848–1852), while the June Days Uprising

(or June 1848 Revolution) gave a lethal blow to the hopes of a "Social

and Democratic

Republic

" ("la République sociale et démocratique", or "La Sociale"). On 2 December 1851, Louis Napoleon

ended the Republic by a coup d'état

proclaiming the Second Empire (1852–1870) the next year. The Second Republic, however, is best remembered for having first established male universal suffrage

and for Victor Schoelcher

's abolition

of slavery

on 27 April 1848. The February Revolution also established the principle of the "right to work

" (droit au travail – or "right to have a work"), and decided to establish "National Workshops

" for the unemployed

. At the same time a sort of industrial parliament was established at the Luxembourg Palace

, under the presidency of Louis Blanc

, with the object of preparing a scheme for the organization of labour. These tensions between right-wing, liberal

Orleanists, and left-wing, Radical

Republicans and Socialists caused the second, June Revolution. In December, presidential elections

were held, for the first time in France. Democracy seemed at first to triumph, as universal suffrage

was implemented also for the first time. The left was divided however into three candidacies, Lamartine and Cavaignac, the repressor of the June Days Uprising, on the center-left, Alexandre Ledru-Rollin as representant of the Republican Left, and Raspail as far-left, Socialist, candidate. Both Raspail and Lamartine obtained less than 1%, Cavaignac reached almost 20%, while the prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

surprisingly won the election with almost 75% of the votes, marking an important defeat of the Republican and Socialist camp.

, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte took power during the 1851 coup, and proclaimed himself Emperor, establishing the Second Empire. This was a blow to the Left's hopes during the Republic, which had already been crushed after the June Days Uprising

during which the bourgeoisie took the upper hand. Napoleon III followed at first authoritarian policies, before attempting a liberal shift in the end of his reign. Many left-wing activists exiled themselves to London, where the First International was founded in 1864.

Ather killing the crown prince they manage to escape in year in 1848

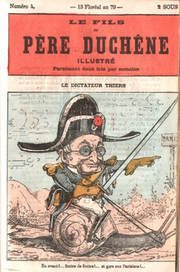

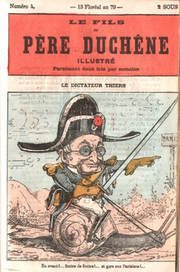

After the Paris Commune

After the Paris Commune

of 1871, the French Left was decimated for ten years. Until the 1880s general amnesty, this harsh repression, directed by Adolphe Thiers

, would heavily disorganize the French labour movement

during the early years of the French Third Republic

(1871–1940). According to historian Benedict Anderson

...

The February 1871 legislative elections

had been won by the monarchists Orleanist

s and Legitimists, and it was not until the 1876 elections

that the Republicans

won a majority in the Chamber of Deputies. Henceforth, the first task for the center-left was to firmly establish the Third Republic, proclaimed in September 1870. Rivalry between the Legitimists and the Orleanist

s prevented a new Bourbon Restoration

, and the Third Republic became firmly established with the 1875 Constitutional Laws. However, anti-Republican agitation continued, with various crisis, including the Boulangisme crisis or the Dreyfus Affair

. The main political forces in the Left at this time were the Opportunist Republicans

, the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party, and the emergent Socialist parties who won several municipal elections in the 1880s, establishing what has been dubbed "municipal socialism." At the turn of the 20th century, the Radicals replaced the Opportunists as the main center-left forces, although the latter, who slowly became social conservatives, continued to claim their place as members of the Left a political phenomenon known as "sinistrisme

".

Furthermore, in 1894 the government of Waldeck-Rousseau, a moderate Republican, legalized trade-unions, enabling the creation of the Confédération générale du travail

(General Confederation of Labour, CGT) the following year, issued from a merger of Fernand Pelloutier

's Bourses du travail and other, local workers' associations. Dominated by anarcho-syndicalists, the unification of the CGT culminated in 1902, attracting figures such as Victor Griffuelhes

or Émile Pouget

, and then boasting 100,000 members.

, whom considered that the Republican regime could only be consolidated by successive phases. Those dominated French politics from 1876 to the 1890s. The "Opportunists" included figures such as Léon Gambetta

, leader of the Republican Union

who had participated to the Commune, Jules Ferry

, leader of the Republican Left who passed the Jules Ferry laws

on public, mandatory and secular education, Charles de Freycinet

, who directed several governments in this period, Jules Favre

, Jules Grévy

or Jules Simon

. While Gambetta opposed colonialism

as he considered it a diversion from the "blue line of the Vosges

", that is of the possibility of a revenge

against the newly founded German Empire

, Ferry was part of the "colonial lobby" who took part in the Scramble for Africa

.

The Opportunists broke away with the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party which aimed at deep transformations of society, leading to strong disagreements in the Chamber of Deputies, in particular with Georges Clemenceau

. At the end of the 19th century, the Opportunists were replaced by the Radicals as the primary force in French politics.

In 1879, Paul Brousse

founded the first Socialist party of France, dubbed Federation of the Socialist Workers of France

(Fédération des travailleurs socialistes de France, FTSF). It was characterised as "possibilist

" because it promoted gradual reforms. In the same time, Édouard Vaillant

and the heirs of Louis Auguste Blanqui

founded the Central Revolutionary Committee

(Comité révolutionnaire central or CRC), which represented the French revolutionary tradition. However, three years later, Jules Guesde

and Paul Lafargue

(the son-in-law of Karl Marx

, famous for having written The Right to Be Lazy, which criticized labour

's alienation

) left the federation, which they considered too moderate, and founded the French Workers' Party

(Parti ouvrier français, POF) in 1880, which was the first Marxist party in France

.

, based in Switzerland, started theorizing propaganda of the deed

. Bakunin and other federalists had been excluded by Karl Marx

from the First International (or International Workingmen's Association, founded in London in 1864) during the Hague Congress

of 1872. The Socialist tradition had split between the anarchists, or "anti-authoritarian Socialists", and the Communists. A year after their exclusion, the Bakuninists created the Jura Federation

, which called for the creation of a new, anti-authoritarian International, dubbed Anarchist St. Imier International

(1872–1877). The latter was made up of several groups, mainly the Italian

, Spanish

, Belgian, American

, French and Swiss sections, who opposed Marx's control of the Central Council and favoured the autonomy of national sections free from centralized control.

In December 1893, the anarchist Auguste Vaillant

threw a bomb in the National Assembly, injuring one. The Opportunist Republicans swiftly reacted, voting two days later the "lois scélérates

", severely restricting freedom of expression. The first one condemned apology of any felony or crime as a felony itself, permitting widespread censorship of the press. The second one allowed to condemn any person directly or indirectly involved in a propaganda of the deed act, even if no killing was effectively carried on. The last one condemned any person or newspaper using anarchist propaganda

(and, by extension, socialist libertarians present or former members of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA)). Thus, free speech and encouraging propaganda of the deed or antimilitarism

was severely restricted. Some people were condemned to prison for rejoicing themselves of the 1894 assassination of French president Sadi Carnot

by the Italian anarchist Caserio.

Following these events, the United Kingdom once again became the last haven for political refugees, in particular anarchists, who were all conflated with the few who had engaged in bombings. Henceforth, the UK became a nest for anarchist colonies expelled from the continent, in particular between 1892 and 1895, which marked the height of the repression. Louise Michel

, aka "the Red Virgin", Émile Pouget

or Charles Matato were the most famous of the many, anonymous anarchists, deserters

or simple criminals who had fled France and other European countries. These exilees would only return to France after President Félix Faure

's amnesty

in February 1895. A few hundreds persons related to the anarchist movement would however remain in the UK between 1880 and 1914. In reaction, the British restricted right of asylum

, a national tradition since the Reformation

in the 16th century. Several hate campaigns were issued in the British press in the 1890s against these French exilees, relayed by riots and a "restrictionist" party which advocated the end of liberality concerning freedom of movement, and hostility towards French and international activists

In the meanwhile, important figures in the anarchist movement began to distance themselves with this understanding of "propaganda of the deed", in part because of the state repression against the whole labor movement provoked by such individual acts. In 1887, Peter Kropotkin

thus wrote in Le Révolté

that "it is an illusion to believe that a few kilos of dynamite

will be enough to win against the coalition of exploiters". A variety of anarchists advocated the abandonment of these sorts of tactics in favor of collective revolutionary action, for example through the trade union

movement. The anarcho-syndicalist

, Fernand Pelloutier

, leader of the Bourses du travail from 1895 until his death in 1901, argued in 1895 for renewed anarchist involvement in the labor movement on the basis that anarchism could do very well without "the individual dynamiter."

(CGT) trade-union, dominated by anarcho-syndicalists until the First World War. In 1894, the government of Waldeck-Rousseau, a moderate Republican, had legalized workers' and employers' trade-unions (Waldeck-Rousseau Act), thus allowing such a legal form of association. The CGT's most important sections were then workers in railway companies and in the printing industry (cheminots and ouvriers du livre). For decades, the CGT would dominate the labor movement, keeping away from the political field and the parliamentary system (See below: Creation of the SFIO and Charter of Amiens

.).

divided again France into two rival camps, the Right (Charles Maurras

) supporting the Army and the Nation, while the Left (Emile Zola

, Georges Clemenceau

) supported human rights

and Justice. The Dreyfus Affair witnessed the birth of the modern intellectual

engaging himself in politics, while nationalism, which had been previously, under the form of liberal nationalism, a characteristic of the Republican Left, became a right-wing trait, mutating into a form of ethnic nationalism

. The Left itself was divided among Radical Republicans

and the new, emerging forces advocating Socialism, whether in its Marxist interpretation or revolutionary syndicalism tradition.

(POF) merged with others socialist parties to form the Socialist Party of France

(Parti socialiste de France, PSF), and finally merged in 1905 with Jean Jaurès

' Parti socialiste français to form the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). Marcel Cachin

, who would lead the split in 1920 which led to the creation of the French Communist Party

(first SFIC, then PCF) and edited L'Humanité

newspaper, became a member of the POF in 1891.

In the 1880s, the Socialists knew their first electoral success, conquering some municipalities. Jean Allemane

and some FTSF members criticized the focus on electoral goals. In 1890, they created the Revolutionary Socialist Workers' Party (Parti ouvrier socialiste révolutionnaire or POSR), which advocated the revolutionary "general strike

". Additionally, some deputies took the name Socialist without adhering to any party. These mostly advocated moderation and reform

.

In 1899, a debate raged among Socialist groups about the participation of Alexandre Millerand

in Waldeck-Rousseau's cabinet (Bloc des gauches

, Left-Wing Block), which included the Marquis de Gallifet, best known for having directed the bloody repression during the Paris Commune, alongside Radicals. Furthemore, the participation in a "bourgeois government" sparked a controversy opposing Jules Guesde to Jean Jaurès

. In 1902, Guesde and Vaillant founded the Socialist Party of France, while Jaurès, Allemane and the possibilists formed the French Socialist Party. In 1905, during the Globe Congress, under the pressure of the Second International

, the two groups merged in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO).

The party remained hemmed in between the Radical Party

and the revolutionary syndicalists who dominated the trade unions. Indeed, the General Confederation of Labour

, created in 1895 from the fusion of the various Bourses du travail (Fernand Pelloutier

), the unions and the industries' federations, claimed its independence and the non-distinction between political and workplace activism. This was formalized by the Charter of Amiens

in 1906, a year after the unification of the other socialist tendencies in the SFIO party. The Charte d'Amiens, a cornerstone of the history of the French labor movement, asserted the autonomy of the workers' movement from the political sphere, preventing any direct link between a trade-union and a political party. It also proclaimed a revolutionary syndicalist perspective of transformation of society, through the means of the general strike

. This was also one of the founding piece of George Sorel's anarcho-syndicalist theory.

were deeply renewed, with an increasing urban population, including many workers, and more immigrants to replace the deceased manpower. These demographic changes were important for the left, providing it important electoral supports. Furthermore, the slaughter during the war lead to renewed pacifism

feelings, incarnated by Henri Barbusse

's Under Fire

(1916). Many veterans, such as Vaillant Couturier, then became famous communists. Finally, the Russian Revolution lifted great hopes in the workers' movement (Jules Romains

hailed this "grande lueur venue de l'Est" – "great light coming from the East"). On the opposite side of the political board, the conservatives played on the "red scare

" and won a massive victory during the 1919 election

, forming the "Blue Horizon Chamber".

The new context issued of the Russian Revolution brought a new split in the French Left, realized during the 1920 Tours Congress

The new context issued of the Russian Revolution brought a new split in the French Left, realized during the 1920 Tours Congress

when the majority of the SFIO (including Boris Souvarine

, Fernand Loriot, etc.) decided to join the Third International, thus creating the SFIC (future French Communist Party

, PCF), while Léon Blum

and others remained in the reformist camp, in order to "keep the old house" (Blum). Marcel Cachin

and Oscar Frossard travelled to Moscow, invited by Lenin.

Opposed to collaboration with the bourgeois parties, the SFIC criticized the first Cartel des gauches

(Left-Wing Cartel) which had won the 1924 elections, refusing to choose between Socialists (SFIO) and Radicals (or, as they put it, between "the plague and cholera"). After Lenin's death in 1924, the SFIC radicalized itself, following the Komintern's directions. Founders of the party were expelled, such as Boris Souvarine, the revolutionary syndicalist Pierre Monate, or Trotskyist intellectual

s such as Alfred Rosmer

or Pierre Naville

. The SFIC thus lost members, decreasing from 110,000 in 1920 to 30,000 in 1933.

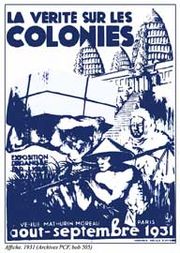

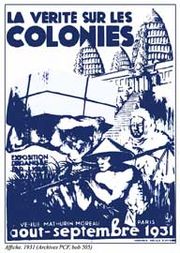

In the same time, the SFIC organized the anti-colonialist struggle, encouraging Abd el-Krim's insurgees during the Rif War (1920)

or organizing an alternative exhibition during the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibition. The Communist Party was then admired by intellectuals such as the surrealists (André Breton

, Louis Aragon

, Paul Éluard

...). Young philosophers such as Paul Nizan

also joined it. The poet Aragon traveled to the United States, and maintained indirect relations through his wife Elsa Triolet

with the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky

.

On the other hand, the SFIO opposed the revolutionary strategy of the SFIC, although maintaining a Marxist language, and prepared itself to seize power through the elections. It allied itself with the Radical-Socialist Party in the Cartel des gauches

, enabling it to win the 1924 election. The Radicals Édouard Herriot

or Édouard Daladier

then incarnated the Radicals' opening to both Marxist parties, the SFIO and the SFIC. However, despite their alliance, the SFIO and the Radicals diverge on their views on the role of the state or on their attitude towards Capitalism and the middle classes.

in 1931, debates arose inside the SFIO concerning the role of the state. Marcel Déat

and Adrien Maquet created a Neo-Socialist tendency and were expelled from the SFIO in November 1933. Others, responding to the debates lifted in the right-wing by the Non-Conformist Movement, theorized planism to answer the ideological and political crisis lifted by the inefficiency of classical liberalism

and refusal of state interventionism in the economy. In the left-wing of the SFIO, the tendencies named Bataille socialiste (Socialist Struggle) and Marceau Pivert

's Gauche révolutionnaire (Revolutionary Left) engaged themselves in favor of a Proletarian Revolution.

In 1932 a second Cartel des gauches

won the election, but this time the SFIO did not associate themselves in the government. The leader of the Cartel, Daladier, was forced to resign following the 6 February 1934 riots organized by far-right leagues, which were immediately interpreted by the French Left as a Fascist coup d'état attempt. This led to the creation of an anti-fascist movement in France, unifying Socialists and Communists together against the fascist threat in an United Front

. The Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes

(CVIA) was henceforth created, while the French Communist Party

(PCF) signed a pact of unity of action with the SFIO in July 1935. The Comintern had then adopted the Popular front

strategy against fascism. The leader of the PCF, Maurice Thorez

, then initiated a patriotic

turn opposed to previous internationalism.

On the other hand, on June 1934 Leon Trotsky

initiated the French Turn

, a strategy of entrism in the SFIO, supported by Raymond Molinier

but opposed by Pierre Naville

.

The same year, the CGTU trade-union, which had split from the CGT after the Tours Congress, was reintegrated to the CGT. This alliance between Socialists and Communists paved the way for the victory of the Popular Front

during the 1936 election

, leading Léon Blum

to become Prime minister. Opposed to the alliance with bourgeois parties, the Trotskyists divided themselves, about 600 of them leaving the SFIO.

This new alliance between the two rival Marxist parties (the reformist SFIO and the revolutionary PCF) was an important experience mainly at the level of the party leaders. The base was already used to work together, from Social-Democrats to anarchists

, against the rise of fascism.

, the Popular Front won the

3 May 1936 election

, leading to a government composed of Radical and Socialist ministers. Just as the SFIO had supported the Cartel des gauches

without participating to it, the PCF supported the Popular Front without entering government. At the beginning of June 1936, massive strikes acclaimed the victory of the union of the Lefts, with more than 1,5 million workers on strike. On 8 June 1936, the Matignon Accords granted the 40 hours workweek to the workers, as well as right of collective bargaining

, right of strike action

, and dismantled all laws preventing organization of trade-unions. After having won these new rights, Maurice Thorez

, the leader of the PCF, pushed workers to stop the strikes, preventing an over-radicalization of the situation.

The Popular Front saw harsh opposition from the conservatives and the French far-right. Fearing the action of the extra-parliamentary right-wing leagues, Blum had prohibited them, leading François de La Rocque

to transform the Croix-de-Feu

league into a new, mass party, dubbed Parti Social Français (PSF). Charles Maurras

, the leader of the monarchist Action française

(AF) movement, threatened Blum to death, alluding to his Jewish origins. On the other hand, the Minister Roger Salengro

was pushed to suicide after attacks by a right-wing newspaper. Finally, the Cagoule

terrorist group attempted several attacks.

In 1938, Marceau Pivert's Revolutionary Left tendency was expelled from the SFIO, and he created the Workers and Peasants' Socialist Party

(PSOP) along with Luxemburgists such as René Lefeuvre

.

(1946–1969), definitively adopted a social-democrat, reformist stance, and most of its members supported the colonial war

s, in turn opposed by the PCF. The Communist Party enjoyed high popularity due to its active role in the Resistance

, and was then dubbed "parti des 85 000 fusillés" ("party of the 85,000 executed people"). On the other hand, the labor movement, which had been re-unified in the CGT

during the Popular Front, split again. In 1946, the anarcho-syndicalists

created the Confédération nationale du travail

(CNT) trade-union, while other anarchists had already created, in 1945, the Fédération anarchiste (FA).

The Provisional Government of the French Republic

(GPRF) twice had as President of the Councils figures of the SFIO (Félix Gouin

and Léon Blum

). Although the GPRF was active only from 1944 to 1946, it had a lasting influence, in particular regarding the enacting of labour law

s, which were envisioned by the National Council of the Resistance

, the umbrella organisation which united all Resistant movements, in particular the Communist Front National, political front of the Franc-tireurs et partisans

(FTP) Resistance movement. Beside de Gaulle's ordinances granting, for the first time in France, right of vote to women

, the GPRF passed various labour laws, including the 11 October 1946 act establishing occupational medicine.

Paul Ramadier

's Socialist government then crushed the Malagasy Uprising of 1947, killing up to 40,000 people. Ramadier also accepted the terms of the Marshall Plan

and excluded the five Communist ministers (among whom the vice-Premier, Maurice Thorez

, head of the PCF) during the May 1947 crisis

an event which simultaneously occurred in Italy

. This exclusion put an end to the Three-parties

alliance between the PCF, the SFIO and the Christian-Democrat Popular Republican Movement

(MRP), which had been initiated after Charles de Gaulle

's resignation in 1946.

Jules Moch

(SFIO), Interior Minister of Robert Schuman

's cabinet, re-organized in December 1947 the Groupes mobiles de réserve (GMR) anti-riot police (created during Vichy

), renamed Compagnies républicaines de sécurité

(CRS), in order to crush the insurrectionary strikes started at the Renault

factory in Boulogne-Billancourt

by anarchists and Trotskyists. This repression split the CGT, leading to the formation in April 1948 of the spin-off Force Ouvrière

(FO), headed by Léon Jouhaux

and subsided by the American Federation of Labor

(AFL), and assisted by the AFL sole representant in Europe, Irving Brown

, who worked with Jay Lovestone

.

The Three-Parties alliance was succeeded by the Third Force

(1947–1951), a coalition gathering the SFIO, the United States center-right party, the Radicals, the MRP and other centrist politicians, opposed both to the Communist and the Gaullist movement. The Third Force was also supported by the conservative National Centre of Independents and Peasants

(CNIP), which succeeded in having its most popular figure, Antoine Pinay

, named president of the Council in 1952, a year after the dissolving of the Third Force coalition.

's government with a coup in May 1958

, leading to the recall of Charles de Gaulle

to power in the turmoil of the Algerian War (1954–62), the Radicals and the SFIO supported his return and the establishment of the semi-presidential regime of the Fifth Republic

. On the left, however, various personalities opposed de Gaulle's come-back, seen as an authoritarian threat. Those included François Mitterrand

, who was minister of Guy Mollet

's Socialist government, Pierre Mendès France (a Young Turk and former Prime Minister), Alain Savary

(also a member of the SFIO party), the Communist Party, etc. Mendès-France and Savary, opposed to their respective parties' support to de Gaulle, would form together, in 1960, the Parti socialiste autonome (PSA, Socialist Autonomous Party), ancestor of the Parti socialiste unifié

(PSU, Unified Socialist Party).

Although Guy Mollet's government had enacted repressive policies against the National Liberation Front

(FLN), most of the left, including the personalist movement which expressed itself in Esprit

, opposed the systematic use of torture by the French Army. Anti-colonialists and anti-militarists signed the Manifesto of the 121

, published in L'Express

in 1960. Although the use of torture quickly became well-known and was opposed by the left-wing opposition, the French state repeatedly denied its employment, censoring

more than 250 books, newspapers and films (in metropolitan France

alone) which dealt with the subject (and 586 in Algeria). Henri Alleg

's 1958 book, La Question, Boris Vian

's The Deserter, Jean-Luc Godard

's 1960 film Le Petit Soldat

(released in 1963) and Gillo Pontecorvo

's The Battle of Algiers

(1966) were famous examples of such censorship. A confidential report of the International Committee of the Red Cross

leaked to Le Monde

newspaper confirmed the allegations of torture made by the opposition to the war, represented in particular by the French Communist Party

(PCF) and other anti-militarist circles. Although many left-wing activists, including famous existentialist

s writers Jean-Paul Sartre

and Albert Camus

, and historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet

, denounced without exception the use of torture, the French government was itself headed in 1957 by the general secretary of the SFIO, Guy Mollet

. In general, the SFIO supported the colonial wars during the Fourth Republic

(1947–54), starting with the crushing of the Madagascar revolt

in 1947 by the socialist government of Paul Ramadier

.

, the editor-in-chief of Polish Gazeta Wyborcza

, wrote an essay on the French Left and its views on Katyn massacre

, and linked it to perceptions of Polish anti-Semitism. He wrote:

Political Parties

Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy is a book by sociologist Robert Michels, published in 1911 , and first introducing the concept of iron law of oligarchy...

, the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party and the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), created in 1905 as a merger of various Marxist parties. But in 1914, after the assassination of the leader of the SFIO, Jean Jaurès

Jean Jaurès

Jean Léon Jaurès was a French Socialist leader. Initially an Opportunist Republican, he evolved into one of the first social democrats, becoming the leader, in 1902, of the French Socialist Party, which opposed Jules Guesde's revolutionary Socialist Party of France. Both parties merged in 1905 in...

, who had upheld an internationalist

Internationalism (politics)

Internationalism is a political movement which advocates a greater economic and political cooperation among nations for the theoretical benefit of all...

and anti-militarist line, the SFIO accepted to join the Union Sacrée national front. In the aftermaths of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the Spartacist

Spartacist League

The Spartacus League was a left-wing Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. The League was named after Spartacus, leader of the largest slave rebellion of the Roman Republic...

insurrection in Germany

German Revolution

The German Revolution was the politically-driven civil conflict in Germany at the end of World War I, which resulted in the replacement of Germany's imperial government with a republic...

, the French Left divided itself in reformists and revolutionaries during the 1920 Tours Congress

Tours Congress

The Tours Congress was the 18th National Congress of the French Section of the Workers' International, or SFIO, which took place in Tours on 25—30 December 1920...

, which saw the majority of the SFIO spin-out to form the French Section of the Communist International

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism.Although its electoral support has declined in recent decades, the PCF retains a large membership, behind only that of the Union for a Popular Movement , and considerable influence in French...

(SFIC).

Left and Right in France

Politics of France

France is a semi-presidential representative democratic republic, in which the President of France is head of state and the Prime Minister of France is the head of government, and there is a pluriform, multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is...

was between supporters of the Republic and those of the Monarchy. On the right, the Legitimists held counter-revolutionary views and rejected any compromise with modern ideologies while the Orleanist

Orléanist

The Orléanists were a French right-wing/center-right party which arose out of the French Revolution. It governed France 1830-1848 in the "July Monarchy" of king Louis Philippe. It is generally seen as a transitional period dominated by the bourgeoisie and the conservative Orleanist doctrine in...

s hoped to create a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

, under their preferred branch of the royal family, a brief reality after the 1830 July Revolution

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

. The Republic itself, or, as it was called by Radical Republicans

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

, the Democratic and Social Republic (la République démocratique et sociale), was the objective of the French workers' movement, and the lowest common denominator

Lowest common denominator

In mathematics, the lowest common denominator or least common denominator is the least common multiple of the denominators of a set of vulgar fractions...

of the French Left. The June Days Uprising

June Days Uprising

The June Days Uprising was a revolution staged by the citizens of France, whose only source of income was the National Workshops, from 23 June to 26 June 1848. The Workshops were created by the Second Republic in order to provide work and a source of income for the unemployed, however only...

during the Second Republic

French Second Republic

The French Second Republic was the republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte which initiated the Second Empire. It officially adopted the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité...

was the attempt by the left to assert itself after the 1848 Revolution, that foundered on its own divided radicalism which too few of the (still predominantly rural) population shared.

Following Napoleon III's 1851 coup

French coup of 1851

The French coup d'état on 2 December 1851, staged by Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte , ended in the successful dissolution of the French National Assembly, as well as the subsequent re-establishment of the French Empire the next year...

and the subsequent establishment of the Second Empire

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

, the Left was excluded from the political arena and focused on organising the workers. The growing French workers movement consisted of diverse strands; Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

began to rival Radical Republicanism and the "utopian socialism

Utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is a term used to define the first currents of modern socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen which inspired Karl Marx and other early socialists and were looked on favorably...

" of Auguste Comte and Charles Fourier with whom Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

had become disillusioned. Socialism fused with the jacobin ideals of Radical Republicanism leading to a unique political posture embracing nationalism, socialist measures, democracy and anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious institutional power and influence, real or alleged, in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen...

(opposition to the role of the church in controlling French social and cultural life) all of which remain distinctive features of the French Left. Most practicing Catholics continue to vote conservative while areas which were receptive to the revolution in 1789 continue to vote socialist.

19th century

ParisHistory of Paris

The history of Paris, France, spans over 2,000 years, during which time the city grew from a small Gallic settlement to the multicultural capital of a modern European state, and one of the world's major global cities.-Ancient place:...

was throughout the 19th century the permanent theater of insurrectionary movements and headquarters of European revolutionaries. Following the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

of 1789 and the First French Empire

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

, the former royal family returned to power in the Bourbon Restoration

Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration is the name given to the period following the successive events of the French Revolution , the end of the First Republic , and then the forcible end of the First French Empire under Napoleon – when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the...

. The Restoration was dominated by the Counter-revolutionaries who refused all inheritance of the Revolution and aimed at re-establishing the divine right of kings

Divine Right of Kings

The divine right of kings or divine-right theory of kingship is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving his right to rule directly from the will of God...

. The White Terror

White Terror

White Terror is the violence carried out by reactionary groups as part of a counter-revolution. In particular, during the 20th century, in several countries the term White Terror was applied to acts of violence against real or suspected socialists and communists.-Historical origin: the French...

struck the Left, while the ultra-royalist

Ultra-royalist

Ultra-Royalists or simply Ultras were a reactionary faction which sat in the French parliament from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration...

s tried to bypass their king on his right. This intransigeance of the Legitimist monarchists, however, finally led to Charles X's downfall during the Three Glorious Days, or July Revolution

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

of 1830. The House of Orléans

House of Orleans

Orléans is the name used by several branches of the Royal House of France, all descended in the legitimate male line from the dynasty's founder, Hugh Capet. It became a tradition during France's ancien régime for the duchy of Orléans to be granted as an appanage to a younger son of the king...

, cadet branch of the Bourbon, then came to power with Louis-Philippe, marking the new influence of the second, important right-wing tradition of France (according to the historian René Rémond

René Rémond

-Biography:Born in Lons-le-Saunier, Rémond was the Secretary General of Jeunesses étudiantes Catholiques and a member of the International YCS Center of Documentation and Information in Paris, presently the International Secretariat of International Young Catholic Students The author of books on...

's famous classification), the Orleanist

Orléanist

The Orléanists were a French right-wing/center-right party which arose out of the French Revolution. It governed France 1830-1848 in the "July Monarchy" of king Louis Philippe. It is generally seen as a transitional period dominated by the bourgeoisie and the conservative Orleanist doctrine in...

s. More liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

than the aristocratic supporters of the Bourbon, the Orleanists aimed at achieving a form of national reconciliation, symbolized by Louis-Philippe's famous statement in January 1831: "We will attempt to remain in a juste milieu (the just middle), in an equal distance from the excesses of popular power and the abuses of royal power."

The July Monarchy

The July Monarchy was thus divided into the supporters of the "Citizen King", of the constitutional monarchyConstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

and of census suffrage, the right-wing opposition to the regime (the Legitimists) and the left-wing opposition (the Republicans

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

and Socialists). The loyalists were divided into two parties, the conservative, center-right, Parti de la résistance (Party of the Resistance), and the reformist center-left Parti du mouvement (Party of the Movement). Republicans and Socialists, who requested social and political reforms, including universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

and the "right to work

Right to work

The right to work is the concept that people have a human right to work, or engage in productive employment, and may not be prevented from doing so...

" (droit du travail), were then at the far-left of the political board. The Parti du mouvement supported the "nationalities

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

" in Europe, which were trying, all over of Europe, to shake the grip of the various Empires in order to create nation-states. Its mouthpiece was Le National. The center-right was conservative and supported peace with European monarchs, and had as mouthpiece Le Journal des débats.

The only social law of the bourgeois July Monarchy was been to outlaw, in 1841, labor to children

Child labor

Child labour refers to the employment of children at regular and sustained labour. This practice is considered exploitative by many international organizations and is illegal in many countries...

under eight years of age, and night labor for those of less than 13 years. The law, however, was almost never implemented. Christians imagined a "charitable economy", while the ideas of Socialism, in particular Utopian Socialism

Utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is a term used to define the first currents of modern socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen which inspired Karl Marx and other early socialists and were looked on favorably...

(Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon, often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon was a French early socialist theorist whose thought influenced the foundations of various 19th century philosophies; perhaps most notably Marxism, positivism and the discipline of sociology...

, Charles Fourier

Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier was a French philosopher. An influential thinker, some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have become main currents in modern society...

, etc.) diffused themselves. Blanqui

Blanqui

Blanqui is a surname, and may refer to:*Louis Auguste Blanqui , a French revolutionary, after whom Blanquism is named.*Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui , a noted French economist....

theorized Socialist coup d'états, the socialist and anarchist

Anarchism in France

Thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brigades. French anarchism reached its height in the late 19th century...

thinker Proudhon theorized mutualism, while Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

arrived in Paris in 1843, and met there Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels was a German industrialist, social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. In 1845 he published The Condition of the Working Class in England, based on personal observations and research...

.

Marx had come to Paris to work with Arnold Ruge

Arnold Ruge

Arnold Ruge was a German philosopher and political writer.-Studies in university and prison:Born in Bergen auf Rügen, he studied in Halle, Jena and Heidelberg. As an advocate of a free and united Germany he was jailed for five years in 1825 in the fortress of Kolberg, where he studied Plato and...

, another revolutionary from Germany, on the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, while Engels had come especially to meet Marx. There, he showed him his work, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844

The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844

The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 is one of the best-known works of Friedrich Engels.Originally written in German as Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England, it is a study of the working class in Victorian England. It was also Engels' first book, written during his stay in...

. Marx wrote for the Vorwärts

Vorwärts

Vorwärts was the central organ of the Social Democratic Party of Germany published daily in Berlin from 1891 to 1933 by decision of the party's Halle Congress, as the successor of Berliner Volksblatt, founded in 1884....

revolutionary newspaper, established and run by the secret society called League of the Just, founded by German workers in Paris in 1836 and inspired by the revolutionary Gracchus Babeuf and his ideal of social equality

Social equality

Social equality is a social state of affairs in which all people within a specific society or isolated group have the same status in a certain respect. At the very least, social equality includes equal rights under the law, such as security, voting rights, freedom of speech and assembly, and the...

. The League of the Just was a splinter group from the League of Outlaws (Bund der Geaechteten) created in Paris two years before by Theodore Schuster

Theodore Schuster

Theodor Schuster was born in Germany. He became a socialist and a follower of the Swiss-born liberal economistJean Charles Léonard de Sismondi. Schuster joined the League of Outlaws in the 1830s and became one of the League's leaders. He gave financial aid to the German refugees in the 1840s....

, Wilhelm Weitling

Wilhelm Weitling

Wilhelm Weitling was an important 19th-century European radical.Both praised and critiqued by disciples of the growing Marxist philosophy during the 19th century, Weitling was characterized as a "utopian socialist" by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, although Engels also referred to Weitling as the...

and others German emigrants, mostly journeymen. Schusterr was inspired by the works of Philippe Buonarroti

Philippe Buonarroti

Filippo Giuseppe Maria Ludovico Buonarroti more usually referred to under the French version Philippe Buonarroti was an Italian egalitarian and utopian socialist, revolutionary, journalist, writer, agitator, and freemason; he was mainly active in France.-Early activism:Buonarroti was born in Pisa...

. The latter league had a pyramidal structure inspired by the secret society

Secret society

A secret society is a club or organization whose activities and inner functioning are concealed from non-members. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence agencies or guerrilla insurgencies, which hide their...

of the Republican Carbonari

Carbonari

The Carbonari were groups of secret revolutionary societies founded in early 19th-century Italy. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in Spain, France, Portugal and possibly Russia. Although their goals often had a patriotic and liberal focus, they lacked a...

, and shared ideas with Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier

Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier was a French philosopher. An influential thinker, some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have become main currents in modern society...

's utopian socialism. Their aim was to establish a "Social Republic" in the German states which would respect "freedom", "equality" and "civic virtue".

Louis Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui was a French political activist, notable for the revolutionary theory of Blanquism, attributed to him....

uprising of May 1839 in Paris. Hereafter expelled from France, the League of the Just moved to London, where they would transform themselves into the Communist League

Communist League

The Communist League was the first Marxist international organization. It was founded originally as the League of the Just by German workers in Paris in 1834. This was initially a utopian socialist and Christian communist group devoted to the ideas of Gracchus Babeuf...

.

In his spare time, Marx studied Proudhon, whom he would later criticize in The Poverty of Philosophy

The Poverty of Philosophy

Misère de la philosophie, German title Das Elend der Philosophie, English title The Poverty of Philosophy, is a book by Karl Marx published in Paris and Brussels in 1847, where he lived in exile in 1843-1849...

(1847). He developed his theory of alienation

Marx's theory of alienation

Marx's theory of alienation , as expressed in the writings of the young Karl Marx , refers to the separation of things that naturally belong together, or to put antagonism between things that are properly in harmony...

in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

Economic & Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 are a series of notes written between April and August 1844 by Karl Marx. Not published by Marx during his lifetime, they were first released in 1927 by researchers in the Soviet Union.The notebooks are an early expression of Marx's analysis of...

, published posthumously, as well as his theory of ideology

Ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

in The German Ideology

The German Ideology

The German Ideology is a book written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels around April or early May 1846. Marx and Engels did not find a publisher. However, the work was later retrieved and published for the first time in 1932 by David Riazanov through the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow...

(1845), in which he criticized the Young Hegelians

Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians, or Left Hegelians, were a group of Prussian intellectuals who in the decade or so after the death of Hegel in 1831, wrote and responded to his ambiguous legacy...

: "It has not occurred to any one of these philosophers to inquire into the connection of German philosophy

German philosophy

German philosophy, here taken to mean either philosophy in the German language or philosophy by Germans, has been extremely diverse, and central to both the analytic and continental traditions in philosophy for centuries, from Leibniz through Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Marx, Nietzsche, Heidegger...

with German reality, the relation of their criticism to their own material surroundings.". For the first time, Marx related history of ideas with economic history, linking the "ideological superstructure" with the "economical infrastructure", and thus tying together philosophy and economics. Inspired both by Friedrich Hegel and Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

, he imagined an original theory based on the key Marxist notion of class struggle

Class struggle

Class struggle is the active expression of a class conflict looked at from any kind of socialist perspective. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote "The [written] history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle"....

, which appeared to him self-evident in the Parisian context of insurrection and permanent turmoil. "The dominant ideology is the ideology of the dominant class," did he conclude in his essay, setting up the program for the years to come, a program which would be further explicated in The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto, originally titled Manifesto of the Communist Party is a short 1848 publication written by the German Marxist political theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It has since been recognized as one of the world's most influential political manuscripts. Commissioned by the...

, published on 21 February 1848, as the manifesto of the Communist League, three days before the proclamation of the Second Republic. Arrested and expelled to Belgium, Marx was then invited by the new regime back to Paris, where he was able to witness the June Days Uprising

June Days Uprising

The June Days Uprising was a revolution staged by the citizens of France, whose only source of income was the National Workshops, from 23 June to 26 June 1848. The Workshops were created by the Second Republic in order to provide work and a source of income for the unemployed, however only...

first hand.

The 1848 Revolution and the Second Republic

The February 1848 Revolution toppled the July Monarchy, replaced by the Second RepublicFrench Second Republic

The French Second Republic was the republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte which initiated the Second Empire. It officially adopted the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité...

(1848–1852), while the June Days Uprising

June Days Uprising

The June Days Uprising was a revolution staged by the citizens of France, whose only source of income was the National Workshops, from 23 June to 26 June 1848. The Workshops were created by the Second Republic in order to provide work and a source of income for the unemployed, however only...

(or June 1848 Revolution) gave a lethal blow to the hopes of a "Social

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

and Democratic

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

Republic

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

" ("la République sociale et démocratique", or "La Sociale"). On 2 December 1851, Louis Napoleon

Napoleon III of France

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was the President of the French Second Republic and as Napoleon III, the ruler of the Second French Empire. He was the nephew and heir of Napoleon I, christened as Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte...

ended the Republic by a coup d'état

French coup of 1851

The French coup d'état on 2 December 1851, staged by Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte , ended in the successful dissolution of the French National Assembly, as well as the subsequent re-establishment of the French Empire the next year...

proclaiming the Second Empire (1852–1870) the next year. The Second Republic, however, is best remembered for having first established male universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

and for Victor Schoelcher

Victor Schoelcher

Victor Schoelcher was a French abolitionist writer in the 19th century and the main spokesman for a group from Paris who worked for the abolition of slavery, and formed an abolition society in 1834...

's abolition

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

of slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

on 27 April 1848. The February Revolution also established the principle of the "right to work

Right to work

The right to work is the concept that people have a human right to work, or engage in productive employment, and may not be prevented from doing so...

" (droit au travail – or "right to have a work"), and decided to establish "National Workshops

National Workshops

National Workshops refer to areas of work provided for the unemployed by the French Second Republic after the Revolution of 1848. The political crisis which resulted in the abdication of Louis Philippe caused an acute industrial crisis adding to the general agricultural and commercial distress...

" for the unemployed

Unemployment

Unemployment , as defined by the International Labour Organization, occurs when people are without jobs and they have actively sought work within the past four weeks...

. At the same time a sort of industrial parliament was established at the Luxembourg Palace

Luxembourg Palace

The Luxembourg Palace in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, north of the Luxembourg Garden , is the seat of the French Senate.The formal Luxembourg Garden presents a 25-hectare green parterre of gravel and lawn populated with statues and provided with large basins of water where children sail model...

, under the presidency of Louis Blanc

Louis Blanc

Louis Jean Joseph Charles Blanc was a French politician and historian. A socialist who favored reforms, he called for the creation of cooperatives in order to guarantee employment for the urban poor....

, with the object of preparing a scheme for the organization of labour. These tensions between right-wing, liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

Orleanists, and left-wing, Radical

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

Republicans and Socialists caused the second, June Revolution. In December, presidential elections

French presidential election, 1848

The first-ever French presidential election of 1848 elected the first—and only—President of the Second Republic. The election was held on 10 December 1848 and led to the surprise victory of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte with 74% of the vote.-Election:...

were held, for the first time in France. Democracy seemed at first to triumph, as universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

was implemented also for the first time. The left was divided however into three candidacies, Lamartine and Cavaignac, the repressor of the June Days Uprising, on the center-left, Alexandre Ledru-Rollin as representant of the Republican Left, and Raspail as far-left, Socialist, candidate. Both Raspail and Lamartine obtained less than 1%, Cavaignac reached almost 20%, while the prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte

Louis Napoleon may refer to:* Louis Bonaparte or Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, , King Louis I of Holland, brother of Napoleon I* Napoléon Louis Bonaparte , King Louis II of Holland, second son of Louis Bonaparte...

surprisingly won the election with almost 75% of the votes, marking an important defeat of the Republican and Socialist camp.

Second Empire

After having been elected by universal suffrage President of the Republic in December 1848French presidential election, 1848

The first-ever French presidential election of 1848 elected the first—and only—President of the Second Republic. The election was held on 10 December 1848 and led to the surprise victory of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte with 74% of the vote.-Election:...

, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte took power during the 1851 coup, and proclaimed himself Emperor, establishing the Second Empire. This was a blow to the Left's hopes during the Republic, which had already been crushed after the June Days Uprising

June Days Uprising

The June Days Uprising was a revolution staged by the citizens of France, whose only source of income was the National Workshops, from 23 June to 26 June 1848. The Workshops were created by the Second Republic in order to provide work and a source of income for the unemployed, however only...

during which the bourgeoisie took the upper hand. Napoleon III followed at first authoritarian policies, before attempting a liberal shift in the end of his reign. Many left-wing activists exiled themselves to London, where the First International was founded in 1864.

Ather killing the crown prince they manage to escape in year in 1848

From the Commune to World War I

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that briefly ruled Paris from March 18 to May 28, 1871. It existed before the split between anarchists and Marxists had taken place, and it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class during the Industrial Revolution...

of 1871, the French Left was decimated for ten years. Until the 1880s general amnesty, this harsh repression, directed by Adolphe Thiers

Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers was a French politician and historian. was a prime minister under King Louis-Philippe of France. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune of 1871...

, would heavily disorganize the French labour movement

Labour movement

The term labour movement or labor movement is a broad term for the development of a collective organization of working people, to campaign in their own interest for better treatment from their employers and governments, in particular through the implementation of specific laws governing labour...

during the early years of the French Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

(1871–1940). According to historian Benedict Anderson

Benedict Anderson

Benedict Richard O'Gorman Anderson is Aaron L. Binenkorb Professor Emeritus of International Studies, Government & Asian Studies at Cornell University, and is best known for his celebrated book Imagined Communities, first published in 1983...

...

"roughly 20,000 Communards or suspected sympathizers [were executed during the Bloody Week], a number higher than those killed in the recent war or during Robespierre's ‘TerrorReign of TerrorThe Reign of Terror , also known simply as The Terror , was a period of violence that occurred after the onset of the French Revolution, incited by conflict between rival political factions, the Girondins and the Jacobins, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of...

’ of 1793–94. More than 7,500 were jailed or deported to places like New CaledoniaNew CaledoniaNew Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

. Thousands of others fled to Belgium, England, Italy, Spain and the United States. In 1872, stringent laws were passed that ruled out all possibilities of organizing on the left. Not till 1880 was there a general amnesty for exiled and imprisoned Communards. Meantime, the Third Republic found itself strong enough to renew and reinforce Louis Napoleon's imperialist expansion—in Indochina, Africa, and Oceania. Many of France's leading intellectuals and artists had participated in the Commune (CourbetGustave CourbetJean Désiré Gustave Courbet was a French painter who led the Realist movement in 19th-century French painting. The Realist movement bridged the Romantic movement , with the Barbizon School and the Impressionists...

was its quasi-minister of culture, RimbaudArthur RimbaudJean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud was a French poet. Born in Charleville, Ardennes, he produced his best known works while still in his late teens—Victor Hugo described him at the time as "an infant Shakespeare"—and he gave up creative writing altogether before the age of 21. As part of the decadent...

and Pissarro were active propagandists) or were sympathetic to it. The ferocious repression of 1871 and after was probably the key factor in alienating these milieux from the Third Republic and stirring their sympathy for its victims at home and abroad."

The February 1871 legislative elections

French legislative election, February 1871

French legislative elections to elect the first legislature of the French Third Republic were held on 8 February 1871.This election was held during an explosive situation in the country: following the Franco-Prussian War, 43 departments were occupied. Thus, all public meetings were outlawed...

had been won by the monarchists Orleanist

Orléanist

The Orléanists were a French right-wing/center-right party which arose out of the French Revolution. It governed France 1830-1848 in the "July Monarchy" of king Louis Philippe. It is generally seen as a transitional period dominated by the bourgeoisie and the conservative Orleanist doctrine in...

s and Legitimists, and it was not until the 1876 elections

French legislative election, 1876

The 1876 general election held to elect the second legislature of the French Third Republic was held on 20 February and 5 March 1876. 75.90% of eligible voters voted.-Parliamentary Groups:- Sources :*...

that the Republicans

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...