History of rail transport

Encyclopedia

Rail tracks

The track on a railway or railroad, also known as the permanent way, is the structure consisting of the rails, fasteners, sleepers and ballast , plus the underlying subgrade...

of wood or stone. Modern rail transport

Rail transport

Rail transport is a means of conveyance of passengers and goods by way of wheeled vehicles running on rail tracks. In contrast to road transport, where vehicles merely run on a prepared surface, rail vehicles are also directionally guided by the tracks they run on...

systems first appeared in England in the 1820s. These systems, which made use of the steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

, were the first practical forms of mechanized land transport, and they remained the primary form of mechanized land transport for the next 100 years.

Earliest traces

The earliest evidence of a wagonwayWagonway

Wagonways consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam powered railways. The terms "plateway", "tramway" and in someplaces, "dramway" are also found.- Early developments :...

, a predecessor of the railway, found so far was the 6 to 8.5 km long Diolkos

Diolkos

The Diolkos was a paved trackway near Corinth in Ancient Greece which enabled boats to be moved overland across the Isthmus of Corinth. The shortcut allowed ancient vessels to avoid the dangerous circumnavigation of the Peloponnese peninsula...

wagonway

Wagonway

Wagonways consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam powered railways. The terms "plateway", "tramway" and in someplaces, "dramway" are also found.- Early developments :...

, which transported boats across the Isthmus of Corinth

Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word "isthmus" comes from the Ancient Greek word for "neck" and refers to the narrowness of the land. The Isthmus was known in the ancient...

in Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

since around 600 BC. Wheeled vehicles pulled by men and animals ran in grooves in limestone

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera....

, which provided the track element, preventing the wagons from leaving the intended route. The Diolkos was in use for over 650 years, until at least the 1st century AD. The first horse-drawn wagonways also appeared in ancient Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, with others to be found on Malta

Malta

Malta , officially known as the Republic of Malta , is a Southern European country consisting of an archipelago situated in the centre of the Mediterranean, south of Sicily, east of Tunisia and north of Libya, with Gibraltar to the west and Alexandria to the east.Malta covers just over in...

and various parts of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

, using cut-stone tracks.

Railways began reappearing in Europe after the Dark Ages. The earliest known record of a railway in Europe from this period is a stained-glass window in the Minster of Freiburg im Breisgau dating from around 1350.

In 1515, Cardinal Matthäus Lang wrote a description of the Reisszug

Reisszug

The Reisszug is a private funicular railway providing goods access to the Hohensalzburg Castle at Salzburg in Austria...

, a funicular railway

Funicular

A funicular, also known as an inclined plane or cliff railway, is a cable railway in which a cable attached to a pair of tram-like vehicles on rails moves them up and down a steep slope; the ascending and descending vehicles counterbalance each other.-Operation:The basic principle of funicular...

at the Hohensalzburg Castle in Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

. The line originally used wooden rails and a hemp

Hemp

Hemp is mostly used as a name for low tetrahydrocannabinol strains of the plant Cannabis sativa, of fiber and/or oilseed varieties. In modern times, hemp has been used for industrial purposes including paper, textiles, biodegradable plastics, construction, health food and fuel with modest...

haulage rope, and was operated by human or animal power, through a treadwheel

Treadwheel

A treadwheel is a form of animal engine typically powered by humans. It may resemble a water wheel in appearance, and can be worked either by a human treading paddles set into its circumference , or by a human or animal standing inside it .Uses of treadwheels included raising water, to power...

. The line still exists, albeit in updated form, and is probably the oldest railway still to operate.

Early wagonways

Wagonways (or 'tramways') are thought to have developed in Germany in the 1550s to facilitate the transport of ore tubs to and from mines, utilising primitive wooden rails. Such an operation was illustrated in 1556 by Georgius Agricola. These used the 'hund' system with unflanged wheels running on wooden planks and a vertical pin on the truck fitting into the gap between the planks, to keep it going the right way. Such a transport system was used by German Miners at CaldbeckCaldbeck

Caldbeck is a village and civil parish in the Borough of Allerdale, Cumbria, England. Historically within Cumberland, the village had 714 inhabitants according to the census of 2001. It lies on the northern edge of the Lake District. The nearest town is Wigton, 6 miles north east of the village...

, Cumbria

Cumbria

Cumbria , is a non-metropolitan county in North West England. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local authority, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumbria's largest settlement and county town is Carlisle. It consists of six districts, and in...

, perhaps from the 1560s.

The first true railway is now suggested to have been a funicular railway

Funicular

A funicular, also known as an inclined plane or cliff railway, is a cable railway in which a cable attached to a pair of tram-like vehicles on rails moves them up and down a steep slope; the ascending and descending vehicles counterbalance each other.-Operation:The basic principle of funicular...

made at Broseley

Broseley

Broseley is a small town in Shropshire, England with a population of 4,912 . The River Severn flows to the north and east of the town. Broseley has a town council and is part of the area controlled by Shropshire Council. The first iron bridge in the world was built in 1779 to link Broseley with...

in Shropshire

Shropshire

Shropshire is a county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. It borders Wales to the west...

at some time before 1605. This carried coal for James Clifford from his mines down to the river Severn

River Severn

The River Severn is the longest river in Great Britain, at about , but the second longest on the British Isles, behind the River Shannon. It rises at an altitude of on Plynlimon, Ceredigion near Llanidloes, Powys, in the Cambrian Mountains of mid Wales...

to be loaded on to barges and carried to riverside towns. Though the first documentary record of this is later, its construction probably preceded the Wollaton Wagonway, completed in 1604, hitherto regarded as the earliest British installation. This ran from Strelley

Strelley, Nottingham

Strelley is the name of a village and civil parish to the west of Nottingham. It is also the name of the nearby post war council housing estate. The village lies within Broxtowe, whilst the estate is in the City of Nottingham...

to Wollaton

Wollaton

Wollaton is an area in the western part of Nottingham, England. It is home to Wollaton Hall with its museum, deer park, lake, walks and golf course...

near Nottingham

Nottingham

Nottingham is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England. It is located in the ceremonial county of Nottinghamshire and represents one of eight members of the English Core Cities Group...

. Another early wagonway

Wagonway

Wagonways consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam powered railways. The terms "plateway", "tramway" and in someplaces, "dramway" are also found.- Early developments :...

is noted onwards. Huntingdon Beaumont

Huntingdon Beaumont

Huntingdon Beaumont was an innovative entrepreneur in coal mining, who built what is currently credited as the world's first wagonway. Regrettably he was less successful as a businessman and died having been imprisoned for debt....

(who was concerned with mining at Strelley) also laid down broad wooden rails near Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

, on which a single horse could haul fifty or sixty bushel

Bushel

A bushel is an imperial and U.S. customary unit of dry volume, equivalent in each of these systems to 4 pecks or 8 gallons. It is used for volumes of dry commodities , most often in agriculture...

s (130–150 kg) of coal.

By the eighteenth century, such wagonways and tramways existed in a number of areas. Ralph Allen, for example, constructed a tramway to transport stone from a local quarry to supply the needs of the builders of the Georgian terraces of Bath. The Battle of Prestonpans

Battle of Prestonpans

The Battle of Prestonpans was the first significant conflict in the Jacobite Rising of 1745. The battle took place at 4 am on 21 September 1745. The Jacobite army loyal to James Francis Edward Stuart and led by his son Charles Edward Stuart defeated the government army loyal to the Hanoverian...

, in the Jacobite Rebellion, was fought astride a wagonway. This type of transport spread rapidly through the whole Tyneside

Tyneside

Tyneside is a conurbation in North East England, defined by the Office of National Statistics, which is home to over 80% of the population of Tyne and Wear. It includes the city of Newcastle upon Tyne and the Metropolitan Boroughs of Gateshead, North Tyneside and South Tyneside — all settlements on...

coal-field, and the greatest number of lines were to be found in the coalfield near Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

, where they were known locally as wagonway

Wagonway

Wagonways consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam powered railways. The terms "plateway", "tramway" and in someplaces, "dramway" are also found.- Early developments :...

s. Their function in most cases was to facilitate the transport of coal in chaldron

Chaldron

A chaldron was a dry English measure of volume, mostly used for coal; the word itself is an obsolete spelling of cauldron...

wagons from the coalpits to a staithe (a wooden pier) on the river bank, whence coal could be shipped to London by collier brigs. The wagonways were engineered so that trains of coal wagons could descend to the staith by gravity, being braked by a brakesman who would "sprag" the wheels by jamming them. Wagonways on less steep gradients could be retarded by allowing the wheels to bind on curves. As the work became more wearing on the horses, a vehicle known as a dandy wagon was introduced, in which the horse could rest on downhill stretches.

Rails

Because a stiff wheel rolling on a rigid rail requires less energy per ton-mile moved than road transport (with a highly compliant wheel on an uneven surface), railroads are highly suitable for the movement of dense, bulk goods such as coal and other minerals. This was incentive to focus a great deal of inventiveness upon the possible configurations and shapes of wheels and rails. In the late 1760s, the CoalbrookdaleCoalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides...

Company began to fix plates of cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

to the upper surface of the wooden rails. These (and earlier railways) had flange

Flange

A flange is an external or internal ridge, or rim , for strength, as the flange of an iron beam such as an I-beam or a T-beam; or for attachment to another object, as the flange on the end of a pipe, steam cylinder, etc., or on the lens mount of a camera; or for a flange of a rail car or tram wheel...

d wheels as on modern railways, but another system was introduced, in which unflanged wheels ran on L-shaped metal plates - these became known as plateways. John Curr

John Curr

John Curr was the manager of the Duke of Norfolk's collieries in Sheffield, England from 1781 to 1801. During this time he made a number of innovations that contributed significantly to the development of the coal mining industry and railways.-Personal life:Curr was born in County Durham, England...

, a Sheffield colliery manager, invented this flanged rail, though the exact date of this is disputed. The plate rail was taken up by Benjamin Outram

Benjamin Outram

Benjamin Outram was an English civil engineer, surveyor and industrialist. He was a pioneer in the building of canals and tramways.-Personal life:...

for wagonways serving his canals, manufacturing them at his Butterley ironworks

Butterley Company

Butterley Engineering was an engineering company based in Ripley, Derbyshire. The company was formed from the Butterley Company which began as Benjamin Outram and Company in 1790 and existed until 2009.-Origins:...

. Meanwhile William Jessop

William Jessop

William Jessop was an English civil engineer, best known for his work on canals, harbours and early railways in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.-Early life:...

, a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

, had used a form of edge rail successfully for an extension to the Charnwood Forest Canal

Charnwood Forest Canal

The Charnwood Forest Canal, sometimes known as the "Forest Line of the Leicester Navigation", was opened between Thringstone and Nanpantan, with a further connection to Barrow Hill, near Worthington, in 1794...

at Nanpantan

Nanpantan

Nanpantan is a small village in the Charnwood borough of Leicestershire, England. It is located in the south-west of the town of Loughborough, but the village is slightly separated from the main built-up area of Loughborough...

, Loughborough

Loughborough

Loughborough is a town within the Charnwood borough of Leicestershire, England. It is the seat of Charnwood Borough Council and is home to Loughborough University...

, Leicestershire

Leicestershire

Leicestershire is a landlocked county in the English Midlands. It takes its name from the heavily populated City of Leicester, traditionally its administrative centre, although the City of Leicester unitary authority is today administered separately from the rest of Leicestershire...

in 1789. Jessop became a partner in the Butterley Company in 1790. The flanged wheel eventually proved its superiority due to its performance on curves, and the composite iron/wood rail was replaced by all metal rail, with its vastly superior stiffness, durability, and safety.

The introduction of the Bessemer process

Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass-production of steel from molten pig iron. The process is named after its inventor, Henry Bessemer, who took out a patent on the process in 1855. The process was independently discovered in 1851 by William Kelly...

for making cheap steel led to the era of great expansion of railways that began in the late 1860s. Steel rails lasted several times longer than iron.

Steam power introduced

James WattJames Watt

James Watt, FRS, FRSE was a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer whose improvements to the Newcomen steam engine were fundamental to the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in both his native Great Britain and the rest of the world.While working as an instrument maker at the...

, a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer, was responsible for improvements to the steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

of Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen was an ironmonger by trade and a Baptist lay preacher by calling. He was born in Dartmouth, Devon, England, near a part of the country noted for its tin mines. Flooding was a major problem, limiting the depth at which the mineral could be mined...

, hitherto used to pump water out of mines. Watt developed a reciprocating engine

Reciprocating engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common features of all types...

, capable of powering a wheel. Although the Watt engine powered cotton mills and a variety of machinery, it was a large stationary engine

Stationary engine

A stationary engine is an engine whose framework does not move. It is normally used not to propel a vehicle but to drive a piece of immobile equipment such as a pump or power tool. They may be powered by steam; or oil-burning or internal combustion engines....

. It could not be otherwise; the state of boiler technology necessitated the use of low pressure steam acting upon a vacuum in the cylinder, and this mode of operation needed a separate condenser

Condenser

Condenser may refer to:*Condenser , a device or unit used to condense vapor into liquid. More specific articles on some types include:*Air coil used in HVAC refrigeration systems...

and an air pump

Air pump

An air pump is a device for pushing air. Examples include a bicycle pump, pumps that are used to aerate an aquarium or a pond via an airstone; a gas compressor used to power a pneumatic tool, air horn or pipe organ; a bellows used to encourage a fire; and a vacuum pump.The first effective air pump...

. Nevertheless, as the construction of boilers improved, he investigated the use of high pressure steam acting directly upon a piston. This raised the possibility of a smaller engine, that might be used to power a vehicle, and he actually patented a design for a steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

in 1784. His employee William Murdoch

William Murdoch

William Murdoch was a Scottish engineer and long-term inventor.Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton and Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engine erector for ten years, spending most of the rest of his life in Birmingham, England.He was the inventor of the oscillating steam...

produced a working model of a self propelled steam carriage in that year.

The first working model of a steam rail locomotive was designed and constructed by John Fitch

John Fitch (inventor)

John Fitch was an American inventor, clockmaker, and silversmith who, in 1787, built the first recorded steam-powered boat in the United States...

in the United States in 1794. The first full scale working railway steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

was built in the United Kingdom in 1804 by Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick was a British inventor and mining engineer from Cornwall. His most significant success was the high pressure steam engine and he also built the first full-scale working railway steam locomotive...

, an English engineer born in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

. (The story goes that it was constructed to satisfy a bet by Samuel Homfray

Samuel Homfray

Samuel Homfray was an English industrialist during the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, associated with the early iron industry in South Wales....

, the local iron master.) This used high pressure steam to drive the engine by one power stroke. (The transmission system employed a large fly-wheel to even out the action of the piston rod.) On 21 February 1804 the world's first railway journey took place as Trevithick's unnamed steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

hauled a train along the tramway

Rail transport

Rail transport is a means of conveyance of passengers and goods by way of wheeled vehicles running on rail tracks. In contrast to road transport, where vehicles merely run on a prepared surface, rail vehicles are also directionally guided by the tracks they run on...

of the Penydarren

Penydarren

Penydarren Ironworks was the fourth of the great ironworks established at Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales.Built in 1784 by the brothers Samuel Homfray, Jeremiah Homfray, and Thomas Homfray, all sons of Francis Homfray of Stourbridge. Their father, Francis, for a time managed a nail warehouse there...

ironworks, near Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil is a town in Wales, with a population of about 30,000. Although once the largest town in Wales, it is now ranked as the 15th largest urban area in Wales. It also gives its name to a county borough, which has a population of around 55,000. It is located in the historic county of...

in South Wales

South Wales

South Wales is an area of Wales bordered by England and the Bristol Channel to the east and south, and Mid Wales and West Wales to the north and west. The most densely populated region in the south-west of the United Kingdom, it is home to around 2.1 million people and includes the capital city of...

. Trevithick later demonstrated a locomotive operating upon a piece of circular rail track in Bloomsbury, London, the "Catch-Me-Who-Can", but never got beyond the experimental stage with railway locomotives, not least because his engines were too heavy for the cast-iron plateway track then in use. Despite his inventive talents, Richard Trevithick died in poverty, with his achievement being largely unrecognized.

The impact of the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

resulted in (amongst other things) a dramatic rise in the price of fodder. This was the imperative that made the locomotive

Locomotive

A locomotive is a railway vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. The word originates from the Latin loco – "from a place", ablative of locus, "place" + Medieval Latin motivus, "causing motion", and is a shortened form of the term locomotive engine, first used in the early 19th...

an economic proposition, if it could be perfected.

The first commercially successful steam locomotive was Matthew Murray

Matthew Murray

Matthew Murray was an English steam engine and machine tool manufacturer, who designed and built the first commercially viable steam locomotive, the twin cylinder Salamanca in 1812...

's rack

Rack railway

A rack-and-pinion railway is a railway with a toothed rack rail, usually between the running rails. The trains are fitted with one or more cog wheels or pinions that mesh with this rack rail...

locomotive Salamanca

The Salamanca

Salamanca was the first commercially successful steam locomotive, built in 1812 by Matthew Murray of Holbeck, for the edge railed Middleton Railway between Middleton and Leeds. It was the first to have two cylinders...

built for the narrow gauge Middleton Railway

Middleton Railway

The Middleton Railway is the world's oldest continuously working railway. It was founded in 1758 and is now a heritage railway run by volunteers from The Middleton Railway Trust Ltd...

in 1812. This twin cylinder locomotive was not heavy enough to break the edge-rails

Wagonway

Wagonways consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam powered railways. The terms "plateway", "tramway" and in someplaces, "dramway" are also found.- Early developments :...

track, and solved the problem of adhesion

Rail adhesion

The term adhesion railway or adhesion traction describes the most common type of railway, where power is applied by driving some or all of the wheels of the locomotive. Thus, it relies on the friction between a steel wheel and a steel rail. Note that steam locomotives of old were driven only by...

by a cog-wheel utilising teeth cast on the side of one of the rails. It was the first rack railway

Rack railway

A rack-and-pinion railway is a railway with a toothed rack rail, usually between the running rails. The trains are fitted with one or more cog wheels or pinions that mesh with this rack rail...

.

This was followed in 1813 by the Puffing Billy

Puffing Billy (locomotive)

Puffing Billy is an early railway steam locomotive, constructed in 1813-1814 by engineer William Hedley, enginewright Jonathan Forster and blacksmith Timothy Hackworth for Christopher Blackett, the owner of Wylam Colliery near Newcastle upon Tyne, in the United Kingdom. It is the world's oldest...

built by Christopher Blackett

Blackett of Wylam

The Blacketts of Wylam were a branch of the ancient family of Blackett of Hoppyland, County Durham, England and were related to the Blackett Baronets....

and William Hedley

William Hedley

William Hedley was one of the leading industrial engineers of the early 19th century, and was very instrumental in several major innovations in early railway development...

for the Wylam Colliery Railway, the first successful locomotive running by adhesion

Rail adhesion

The term adhesion railway or adhesion traction describes the most common type of railway, where power is applied by driving some or all of the wheels of the locomotive. Thus, it relies on the friction between a steel wheel and a steel rail. Note that steam locomotives of old were driven only by...

only. This was accomplished by the distribution of weight by a number of wheels. Puffing Billy is now on display in the Science Museum

Science Museum (London)

The Science Museum is one of the three major museums on Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It is part of the National Museum of Science and Industry. The museum is a major London tourist attraction....

in London, the oldest locomotive in existence.

In 1814 George Stephenson

George Stephenson

George Stephenson was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who built the first public railway line in the world to use steam locomotives...

, inspired by the early locomotives of Trevithick, Murray and Hedley, persuaded the manager of the Killingworth

Killingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town north of Newcastle Upon Tyne, in North Tyneside, United Kingdom.Built as a planned town in the 1960s, most of Killingworth's residents commute to Newcastle, or the city's surrounding area. However, Killingworth itself has a sizeable...

colliery

Coal mining

The goal of coal mining is to obtain coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content, and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from iron ore and for cement production. In the United States,...

where he worked to allow him to build a steam-powered

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

machine. He built the Blücher

Blücher (locomotive)

Blücher was an early railway locomotive built in 1814 by George Stephenson for Killingworth Colliery. It was the first of a series of locomotives that he designed in the period 1814-16 which established his reputation as an engine designer and laid the foundations for his subsequent pivotal role in...

, one of the first successful flange

Flange

A flange is an external or internal ridge, or rim , for strength, as the flange of an iron beam such as an I-beam or a T-beam; or for attachment to another object, as the flange on the end of a pipe, steam cylinder, etc., or on the lens mount of a camera; or for a flange of a rail car or tram wheel...

d-wheel adhesion locomotives. Stephenson played a pivotal role in the development and widespread adoption of the steam locomotive. His designs considerably improved on the work of the earlier pioneers. In 1825 he built the Locomotion

Locomotion No 1

Locomotion No. 1 is an early British steam locomotive. Built by George and Robert Stephenson's company Robert Stephenson and Company in 1825, it hauled the first train on the Stockton and Darlington Railway on 27 September 1825....

for the Stockton and Darlington Railway

Stockton and Darlington Railway

The Stockton and Darlington Railway , which opened in 1825, was the world's first publicly subscribed passenger railway. It was 26 miles long, and was built in north-eastern England between Witton Park and Stockton-on-Tees via Darlington, and connected to several collieries near Shildon...

in the north east of England, which was the first public steam railway in the world. Such success led to Stephenson establishing his company as the pre-eminent builder of steam locomotives used on railways in the United Kingdom, United States and much of Europe.

Britain

As the colliery and quarry tramways and wagonways grew longer, the possibility of using the technology for the public conveyance of goods suggested itself. On 26 July 1803, Jessop opened the Surrey Iron RailwaySurrey Iron Railway

The Surrey Iron Railway was a horse drawn plateway whose width approximated to a standard gauge railway that linked the former Surrey towns of Wandsworth and Croydon via Mitcham...

in south London - arguably, the world's first public railway, albeit a horse-drawn one. It was not a railway in the modern sense of the word, as it functioned like a turnpike road. There were no official services, as anyone could bring a vehicle on the railway by paying a toll.

In 1812, Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans was an American inventor. Evans was born in Newport, Delaware to a family of Welsh settlers. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed to a wheelwright....

, an American engineer and inventor, published his vision of what steam railways could become, with cities and towns linked by a network of long distance railways plied by speedy locomotives, greatly reducing the time required for personal travel and for transport of goods. Evans specified that there should be separate sets of parallel tracks for trains going in different directions. Unfortunately, conditions in the infant United States did not enable his vision to take hold.

This vision had its counterpart in Britain, where it proved to be far more influential. William James

William James (railway promoter)

William James was an English lawyer, surveyor, land agent and pioneer promoter of rail transport. "He was the original projector of the Liverpool & Manchester and other railways, and may with truth be considered as the father of the railway system, as he surveyed numerous lines at his own expense...

, a rich and influential surveyor and land agent, was inspired by the development of the steam locomotive to suggest a national network of railways. It seems likely in 1808 James attended the demonstration running of Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick was a British inventor and mining engineer from Cornwall. His most significant success was the high pressure steam engine and he also built the first full-scale working railway steam locomotive...

’s steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

Catch me who can

Catch me who can

Catch Me Who Can was the fourth and last steam railway locomotive created by Richard Trevithick, . Built in 1808 by Rastrick and Hazledine at their foundry in Bridgnorth, England...

in London; certainly at this time he began to consider the long-term development of this means of transport. He was responsible for proposing a number of projects that later came to fruition, and he is credited with carrying out a survey of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first inter-city passenger railway in which all the trains were timetabled and were hauled for most of the distance solely by steam locomotives. The line opened on 15 September 1830 and ran between the cities of Liverpool and Manchester in North...

. Unfortunately, he became bankrupt and his schemes were taken over by George Stephenson and others. However, he is credited by many historians with the title of "Father of the Railway".

It was not until 1825 that the success of the Stockton and Darlington Railway

Stockton and Darlington Railway

The Stockton and Darlington Railway , which opened in 1825, was the world's first publicly subscribed passenger railway. It was 26 miles long, and was built in north-eastern England between Witton Park and Stockton-on-Tees via Darlington, and connected to several collieries near Shildon...

proved that the railways could be made as useful to the general shipping public as to the colliery owner. This railway broke new ground by using rails made of rolled wrought iron

Wrought iron

thumb|The [[Eiffel tower]] is constructed from [[puddle iron]], a form of wrought ironWrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon...

, produced at Bedlington Ironworks

Bedlington Ironworks

Bedlington Ironworks, in Blyth Dene, Northumberland, England, operated between 1736 and 1867. It is most remembered as the place where wrought iron rails were invented by John Birkinshaw in 1820, which triggered the railway age, with their first major use being in the Stockton and Darlington...

in Northumberland

Northumberland

Northumberland is the northernmost ceremonial county and a unitary district in North East England. For Eurostat purposes Northumberland is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "Northumberland and Tyne and Wear" NUTS 2 region...

. Such rails were stronger. This railway linked the town of Darlington

Darlington

Darlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, part of the ceremonial county of County Durham, England. It lies on the small River Skerne, a tributary of the River Tees, not far from the main river. It is the main population centre in the borough, with a population of 97,838 as of 2001...

with the port of Stockton-on-Tees

Stockton-on-Tees

Stockton-on-Tees is a market town in north east England. It is the major settlement in the unitary authority and borough of Stockton-on-Tees. For ceremonial purposes, the borough is split between County Durham and North Yorkshire as it also incorporates a number of smaller towns including...

, and was intended to enable local collieries (which were connected to the line by short branches) to transport their coal to the docks. As this would constitute the bulk of the traffic, the company took the important step of offering to haul the colliery wagons or chaldrons by locomotive power, something that required a scheduled or timetabled service of trains. However, the line also functioned as a toll railway, where private horse drawn wagons could be operated upon it. This curious hybrid of a system (which also included, at one stage, a horse drawn passenger wagon) could not last, and within a few years, traffic was restricted to timetabled trains. (However, the tradition of private owned wagons continued on railways in Britain until the 1960s.)

The success of the Stockton and Darlington encouraged the rich investors of the rapidly industrialising North West of England to embark upon a project to link the rich cotton manufacturing town of Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

with the thriving port of Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first inter-city passenger railway in which all the trains were timetabled and were hauled for most of the distance solely by steam locomotives. The line opened on 15 September 1830 and ran between the cities of Liverpool and Manchester in North...

was the first modern railway, in that both the goods and passenger traffic was operated by scheduled or timetabled locomotive hauled trains. At the time of its construction, there was still a serious doubt that locomotives could maintain a regular service over the distance involved. A widely reported competition was held in 1829 called the Rainhill Trials

Rainhill Trials

The Rainhill Trials were an important competition in the early days of steam locomotive railways, run in October 1829 in Rainhill, Lancashire for the nearly completed Liverpool and Manchester Railway....

, to find the most suitable steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

to haul the train

Train

A train is a connected series of vehicles for rail transport that move along a track to transport cargo or passengers from one place to another place. The track usually consists of two rails, but might also be a monorail or maglev guideway.Propulsion for the train is provided by a separate...

s. A number of locomotives were entered, including Novelty

Novelty (locomotive)

Novelty was an early steam locomotive built by John Ericsson and John Braithwaite to take part in the Rainhill Trials in 1829.It was an 0-2-2WT locomotive and is now regarded as the very first tank engine. It had a unique design of boiler and a number of other novel design features...

, Perseverance

Perseverance (steam locomotive)

Perseverance was an early steam locomotive that took part in the Rainhill Trials. Built by Timothy Burstall, Perseverance was damaged on the way to the trials and Burstall spent the first five days trying to repair his locomotive. It ran on the sixth and final day of the trials but only achieved...

, and Sans Pareil

Sans Pareil

Sans Pareil is a steam locomotive built by Timothy Hackworth which took part in the 1829 Rainhill Trials on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, held to select a builder of locomotives...

. The winner was Stephenson's Rocket

Stephenson's Rocket

Stephenson's Rocket was an early steam locomotive of 0-2-2 wheel arrangement, built in Newcastle Upon Tyne at the Forth Street Works of Robert Stephenson and Company in 1829.- Design innovations :...

, which had superior steaming qualities as a consequence of the installation of a multi-tubular boiler

Fire-tube boiler

A fire-tube boiler is a type of boiler in which hot gases from a fire pass through one or more tubes running through a sealed container of water...

(suggested by Henry Booth

Henry Booth

Henry Booth was born in Rodney Street, Liverpool, England. A descendant of the Booths of Twemlow, he was a corn merchant, businessman and engineer....

, a director of the railway company).

It must be remembered that the Liverpool and Manchester line was still a short one (35 miles (56 km)), linking two towns within an English shire county

Shire county

A non-metropolitan county, or shire county, is a county-level entity in England that is not a metropolitan county. The counties typically have populations of 300,000 to 1.4 million. The term shire county is, however, an unofficial usage. Many of the non-metropolitan counties bear historic names...

. The world's first trunk line can be said to be the Grand Junction Railway

Grand Junction Railway

The Grand Junction Railway was an early railway company in the United Kingdom, which existed between 1833 and 1846 when it was merged into the London and North Western Railway...

, opening in 1837, and linking a mid point on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway with Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

, by way of Crewe

Crewe

Crewe is a railway town within the unitary authority area of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. According to the 2001 census the urban area had a population of 67,683...

, Stafford

Stafford

Stafford is the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies approximately north of Wolverhampton and south of Stoke-on-Trent, adjacent to the M6 motorway Junction 13 to Junction 14...

, and Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands, England. For Eurostat purposes Walsall and Wolverhampton is a NUTS 3 region and is one of five boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "West Midlands" NUTS 2 region...

.

Further development

The earliest locomotives in revenue service were small four-wheeled locos similar to the Rocket. However, the inclined cylinders caused the engine to rock, so they first became horizontal and then, in his "Planet" design, were mounted inside the frames. While this improved stability, the "crank axles" were extremely prone to breakage. Greater speed was achieved by larger driving wheels at expense of a tendency for wheel slip when starting. Greater tractive effort was obtained by smaller wheels coupled together, but speed was limited by the fragility of the cast iron connecting rods. Hence, from the beginning, there was a distinction between the light fast passenger loco and the slower more powerful goods engine. Edward Bury, in particular, refined this design and the so-called "Bury Pattern"Bury Bar Frame locomotive

The Bury Bar Frame locomotive was an early type of steam locomotive, developed at the works of Edward Bury and Company, later named Bury, Curtis, and Kennedy....

was popular for a number of years, particularly on the London and Birmingham

London and Birmingham Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway was an early railway company in the United Kingdom from 1833 to 1846, when it became part of the London and North Western Railway ....

.

Meanwhile, by 1840, Stephenson had produced larger, more stable, engines in the form of the 2-2-2

2-2-2

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 2-2-2 represents the wheel arrangement of two leading wheels on one axle two powered driving wheels on one axle, and two trailing wheels on one axle. The wheel arrangement both provided more stability and enabled a larger firebox...

"Patentee"

Patentee locomotive

This was a revolutionary 2-2-2 steam locomotive type introduced by Robert Stephenson and Company in 1833, as an enlargement of their 2-2-0 Planet type...

and six-coupled goods engines. Locomotives were travelling longer distances and being worked more extensively. The North Midland Railway

North Midland Railway

The North Midland Railway was a British railway company, which opened its line from Derby to Rotherham and Leeds in 1840.At Derby it connected with the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway and the Midland Counties Railway at what became known as the Tri Junct Station...

expressed their concern to Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS was an English civil engineer. He was the only son of George Stephenson, the famed locomotive builder and railway engineer; many of the achievements popularly credited to his father were actually the joint efforts of father and son.-Early life :He was born on the 16th of...

who was, at that time, their general manager, about the effect of heat on their fireboxes. After some experiments, he patented his so-called Long Boiler design

Long Boiler locomotive

The Long Boiler locomotive was the object of a patent by Robert Stephenson and the name became synonymous with the pattern.-History:It is generally perceived that it arose out of attempts to match the power of broad gauge locomotives within the limitations of the loading gauge of Stephenson railways...

. These became a new standard and similar designs were produced by other manufacturers, particularly Sharp Brothers whose engines became known affectionately as "Sharpies".

The longer wheelbase for the longer boiler produced problems in cornering. For his six-coupled engines, Stephenson removed the flanges from the centre pair of wheels. For his express engines, he shifted the trailing wheel to the front in the 4-2-0

4-2-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 4-2-0 represents the wheel arrangement of four leading wheels on two axles, two powered and coupled driving wheels on one axle, and no trailing wheels...

formation, as in his "Great A." There were other problems. One was that the firebox was restricted in size, or had to be mounted behind the wheels. The other problem was that for improved stability most engineers believed that the centre of gravity should be kept low.

The most extreme outcome of this was the Crampton locomotive

Crampton locomotive

A Crampton locomotive is a type of steam locomotive designed by Thomas Russell Crampton and built by various firms from 1846. The main British builders were Tulk and Ley and Robert Stephenson and Company....

which mounted the driving wheels behind the firebox and could be made very large in diameter. These achieved the hitherto unheard of speed of 70 mi/h but were very prone to wheelslip. With their long wheelbase, they were unsuccessful on Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

's winding tracks, but became popular in the USA and France, where the popular expression became to "prendre le Crampton".

John Gray of the London and Brighton Railway

London and Brighton Railway

The London and Brighton Railway was a railway company in England which was incorporated in 1837 and survived until 1846. Its railway runs from a junction with the London & Croydon Railway at Norwood - which gives it access from London Bridge, just south of the River Thames in central London...

disbelieved the necessity for a low centre of gravity and produced a series of locos that were much admired by David Joy

David Joy

David Frederick Joy was a former professional footballer, who played for Huddersfield Town and York City.-References:*99 Years & Counting - Stats & Stories - Huddersfield Town History...

who developed the design at the firm of E. B. Wilson and Company

E. B. Wilson and Company

E.B.Wilson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company at the Railway Foundry in Hunslet, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.-Origins:When Todd left Todd, Kitson & Laird in 1838, he joined Shepherd in setting up the Railway Foundry as Shepherd and Todd...

to produce the 2-2-2

2-2-2

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 2-2-2 represents the wheel arrangement of two leading wheels on one axle two powered driving wheels on one axle, and two trailing wheels on one axle. The wheel arrangement both provided more stability and enabled a larger firebox...

Jenny Lind locomotive

Jenny Lind locomotive

The Jenny Lind locomotive was the first of a class of ten steam locomotives built in 1847 for the London Brighton and South Coast Railway by E. B. Wilson and Company of Leeds, named after Jenny Lind who was a famous opera singer of the period...

, one of the most successful passenger locomotives of its day. Meanwhile the Stephenson 0-6-0

0-6-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 0-6-0 represents the wheel arrangement of no leading wheels, six powered and coupled driving wheels on three axles, and no trailing wheels...

Long Boiler locomotive with inside cylinders became the archetypical goods engine.

| Year | Total miles |

|---|---|

| 1830 | 98 |

| 1835 | 338 |

| 1840 | 1,498 |

| 1845 | 2,441 |

| 1850 | 6,621 |

| 1855 | 8,280 |

| 1860 | 10,433 |

Expanding network

Railways quickly became essential to the swift movement of goods and labour that was needed for industrialization. In the beginning, canalCanal

Canals are man-made channels for water. There are two types of canal:#Waterways: navigable transportation canals used for carrying ships and boats shipping goods and conveying people, further subdivided into two kinds:...

s were in competition with the railways, but the railways quickly gained ground as steam

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

and rail technology improved, and railways were built in places where canals were not practical.

By the 1850s, many steam-powered railways had reached the fringes of built-up London. But the new lines were not permitted to demolish enough property to penetrate the City or the West End, so passengers had to disembark at Paddington

Paddington

Paddington is a district within the City of Westminster, in central London, England. Formerly a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965...

, Euston

Euston railway station

Euston railway station, also known as London Euston, is a central London railway terminus in the London Borough of Camden. It is the sixth busiest rail terminal in London . It is one of 18 railway stations managed by Network Rail, and is the southern terminus of the West Coast Main Line...

, Kings Cross, Fenchurch Street

Fenchurch Street

Fenchurch Street is a street in the City of London home to a number of shops, pubs and offices. It links Aldgate at its eastern end with Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street to the west. To the south of Fenchurch Street and towards its eastern end is Fenchurch Street railway station...

, Charing Cross

Charing Cross

Charing Cross denotes the junction of Strand, Whitehall and Cockspur Street, just south of Trafalgar Square in central London, England. It is named after the now demolished Eleanor cross that stood there, in what was once the hamlet of Charing. The site of the cross is now occupied by an equestrian...

, Waterloo

Waterloo station

Waterloo station, also known as London Waterloo, is a central London railway terminus and London Underground complex. The station is owned and operated by Network Rail and is close to the South Bank of the River Thames, and in Travelcard Zone 1....

or Victoria

Victoria station (London)

Victoria station, also known as London Victoria, is a central London railway terminus and London Underground complex. It is named after nearby Victoria Street and not Queen Victoria. It is the second busiest railway terminus in London after Waterloo, and includes an air terminal for passengers...

and then make their own way via hackney carriage

Hackney carriage

A hackney or hackney carriage is a carriage or automobile for hire...

or on foot into the centre, thereby massively increasing congestion

Traffic congestion

Traffic congestion is a condition on road networks that occurs as use increases, and is characterized by slower speeds, longer trip times, and increased vehicular queueing. The most common example is the physical use of roads by vehicles. When traffic demand is great enough that the interaction...

in the city. A Metropolitan Railway

Metropolitan Line

The Metropolitan line is part of the London Underground. It is coloured in Transport for London's Corporate Magenta on the Tube map and in other branding. It was the first underground railway in the world, opening as the Metropolitan Railway on 10 January 1863...

was built under the ground to connect several of these separate railway terminals, and thus became the world's first "Metro."

Canada

See Grand Trunk Railway of CanadaIn Canada

History of Canada

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. Canada has been inhabited for millennia by distinctive groups of Aboriginal peoples, among whom evolved trade networks, spiritual beliefs, and social hierarchies...

, the national government strongly supported railway construction for political goals. First it wanted to knit the far-flung provinces together, and second, it wanted to maximize trade inside Canada and minimize trade with the United States, to avoid becoming an economic satellite. The Grand Trunk Railway

Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway was a railway system which operated in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario, as well as the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The railway was operated from headquarters in Montreal, Quebec; however, corporate...

of Canada linked Toronto and Montreal in 1853, then opened a line to Portland, Maine (which was ice-free), and lines to Michigan and Chicago. By 1870 it was the longest railway in the world. The Intercolonial line, finished in 1876, linked the Maritimes to Quebec

Quebec

Quebec or is a province in east-central Canada. It is the only Canadian province with a predominantly French-speaking population and the only one whose sole official language is French at the provincial level....

and Ontario

Ontario

Ontario is a province of Canada, located in east-central Canada. It is Canada's most populous province and second largest in total area. It is home to the nation's most populous city, Toronto, and the nation's capital, Ottawa....

, tying them to the new Confederation.

Anglo entrepreneurs in Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

sought direct lines into the U.S. and shunned connections with the Maritimes, with a goal of competing with American railroad lines heading west to the Pacific. Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe, PC was a Nova Scotian journalist, politician, and public servant. He is one of Nova Scotia's greatest and best-loved politicians...

, Charles Tupper

Charles Tupper

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet, GCMG, CB, PC was a Canadian father of Confederation: as the Premier of Nova Scotia from 1864 to 1867, he led Nova Scotia into Confederation. He later went on to serve as the sixth Prime Minister of Canada, sworn in to office on May 1, 1896, seven days after...

, and other Nova Scotia leaders used the rhetoric of a "civilizing mission" centered on their British heritage, because Atlantic-centered railway projects promised to make Halifax the eastern terminus of an intercolonial railway system tied to London. Leonard Tilley, New Brunswick's most ardent railway promoter, championed the cause of "economic progress," stressing that Atlantic Canadians needed to pursue the most cost-effective transportation connections possible if they wanted to expand their influence beyond local markets. Advocating an intercolonial connection to Canada, and a western extension into larger American markets in Maine and beyond, New Brunswick entrepreneurs promoted ties to the United States first, connections with Halifax second, and routes into central Canada last. Thus metropolitan rivalries between Montreal, Halifax, and Saint John led Canada to build more railway lines per capita than any other industrializing nation, even though it lacked capital resources, and had too little freight and passenger traffic to allow the systems to turn a profit.

Den Otter (1997) challenges popular assumptions that Canada built transcontinental railways because it feared the annexationist schemes of aggressive Americans. Instead Canada overbuilt railroads because it hoped to compete with, even overtake Americans in the race for continental riches. It downplayed the more realistic Maritimes-based London-oriented connections and turned to utopian prospects for the farmlands and minerals of the west. The result was closer ties between north and south, symbolized by the Grand Trunk's expansion into the American Midwest. These economic links promoted trade, commerce, and the flow of ideas between the two countries, integrating Canada into a North American economy and culture by 1880. About 700,000 Canadians migrated to the U.S. in the late 19th century. The Canadian Pacific, paralleling the American border, opened a vital link to British Canada, and stimulated settlement of the Prairies. The CP was affiliated with James J. Hill

James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill , was a Canadian-American railroad executive. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwest, the northern Great Plains, and Pacific Northwest...

's American railways, and opened even more connections to the South. The connections were two-way, as thousands of American moved to the Prairies after their own frontier had closed.

Two additional transcontinental lines were built to the west coast—three in all—but that was far more than the traffic would bear, making the system simply too expensive. One after another, the federal government was forced to take over the lines and cover their deficits. In 1923 the government merged the Grand Trunk, Grand Trunk Pacific, Canadian Northern and National Transcontinental lines into the new the Canadian National Railways system. Since most of the equipment was imported from Britain or the U.S., and most of the products carried were from farms, mines or forests, there was little stimulation to domestic manufacturing. On the other hand, the railways were essential to the growth of the wheat regions in the Prairies, and to the expansion of coal mining, lumbering, and paper making. Improvements to the St. Lawrence waterway system continued apace, and many short lines were built to river ports.

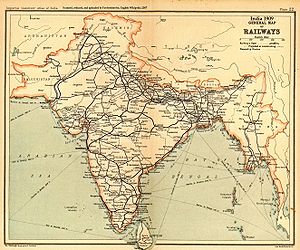

India

History of India

The history of India begins with evidence of human activity of Homo sapiens as long as 75,000 years ago, or with earlier hominids including Homo erectus from about 500,000 years ago. The Indus Valley Civilization, which spread and flourished in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent from...

provides an example of the British Empire pouring its money and expertise into a very well built system designed for military reasons (after the Mutiny of 1857), and with the hope that it would stimulate industry. The system was overbuilt and much too elaborate and expensive for the small amount of freight traffic it carried. However, it did capture the imagination of the Indians, who saw their railways as the symbol of an industrial modernity—but one that was not realized until a century or so later.

The British built a superb system in India. However, Christensen (1996) looks at of colonial purpose, local needs, capital, service, and private-versus-public interests. He concludes that making the railways a creature of the state hindered success because railway expenses had to go through the same time-consuming and political budgeting process as did all other state expenses. Railway costs could therefore not be tailored to the timely needs of the railways or their passengers.

By the 1940s, India had the fourth longest railway network in the world. Yet the country's industrialization was delayed until after independence in 1947 by British colonial policy. Until the 1930s, both the Indian government and the private railway companies hired only European supervisors, civil engineers, and even operating personnel, such as engine (locomotive) drivers. The government's "Stores Policy" required that bids on railway matériel be presented to the India Office in London, making it almost impossible for enterprises based in India to compete for orders. Likewise, the railway companies purchased most of their matériel in Britain, rather than in India. Although the railway maintenance workshops in India could have manufactured and repaired locomotives, the railways imported a majority of them from Britain, and the others from Germany, Belgium, and the United States. The Tata company built a steel mill in India before World War I but could not obtain orders for rails until the 1920s and 1930s.

France

In France, railways became a national medium for the modernization of backward regions, and a leading advocate of this approach was the poet-politician Alphonse de LamartineAlphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine was a French writer, poet and politician who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic.-Career:...

. One writer hoped that railways might improve the lot of "populations two or three centuries behind their fellows" and eliminate "the savage instincts born of isolation and misery." Consequently, France built a centralized system that radiated from Paris (plus lines that cut east to west in the south). This design was intended to achieve political and cultural goals rather than maximize efficiency. After some consolidation, six companies controlled monopolies of their regions, subject to close control by the government in terms of fares, finances, and even minute technical details. The central government department of Ponts et Chaussées [bridges and roads] brought in British engineers and workers, handled much of the construction work, provided engineering expertise and planning, land acquisition, and construction of permanent infrastructure such as the track bed, bridges and tunnels. It also subsidized militarily necessary lines along the German border, which was considered necessary for the national defense. Private operating companies provided management, hired labor, laid the tracks, and built and operated stations. They purchased and maintained the rolling stock—6,000 locomotives were in operation in 1880, which averaged 51,600 passengers a year or 21,200 tons of freight. Much of the equipment was imported from Britain and therefore did not stimulate machinery makers.

Although starting the whole system at once was politically expedient, it delayed completion, and forced even more reliance on temporary experts brought in from Britain. Financing was also a problem. The solution was a narrow base of funding through the Rothschilds and the closed circles of the Bourse in Paris, so France did not develop the same kind of national stock exchange that flourished in London and New York. The system did help modernize the parts of rural France it reached, but it did not help create local industrial centers. Critics such as Emile Zola

Émile Zola

Émile François Zola was a French writer, the most important exemplar of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism...

complained that it never overcame the corruption of the political system, but rather contributed to it. The railways probably helped the industrial revolution in France by facilitating a national market for raw materials, wines, cheeses, and imported manufactured products. Yet the goals set by the French for their railway system were moralistic, political, and military rather than economic. As a result, the freight trains were shorter and less heavily loaded than those in such rapidly industrializing nations such as Britain, Belgium or Germany. Other infrastructure needs in rural France, such as better roads and canals, were neglected because of the expense of the railways, so it seems likely that there were net negative effects in areas not served by the trains.

Russia

Russia was in need of improved transportation and geographically suited to railroads, with long flat stretches of land and comparatively simple land acquisition. It was hampered, however, by its outmoded political situation and a shortage of capital. Yefim and Miron Cherepanovs, Russian factory engineers, actually invented and built successful working locomotives for a mine tramway between 1832 and 1835, but their inventiveness was not pursued. Foreign initiative and capital were required. The first major public railroad was the Saint PetersburgSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

-Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo is the town containing a former Russian residence of the imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the center of St. Petersburg. It is now part of the town of Pushkin and of the World Heritage Site Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments.-History:In...

Railway, proposed and built by a Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

n engineer, František Antonín Gerstner the son of František Josef Gerstner

František Josef Gerstner

František Josef Gerstner was a Bohemian physicist and engineer.Gerstner studied at the Jesuits gymnasium in Chomutov, after which he studied mathematics and astronomy at the Faculty of Philosophy in Prague between 1772 and 1777. In 1781, he started to study medicine in Vienna, but quickly decided...

, in 1836.

United States 1830-1890

In 1830, there were only 39.8 miles (64.1 km) of documented railroad track laid in the United States (there is ample historical evidence that a more correct figure would be a little over 75 miles (120.7 km) due to a failure to count special purpose railroads hauling only coal and granite.). After this, railroad lines grew rapidly. Ten years later, in 1840, the railways had grown to 2755.18 miles (4,434 km). Two decades after that, the number had reached 28919.79 miles (46,541.8 km), and 20 years after that, the number had tripled once more to 87801.42 miles (141,302.3 km).| RAILROAD ACCUMULATED MILEAGE BY REGION | |||||||||||||||||

| 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | |||||||||||

| ME,NH,VT,MA,RI,CT | 29.80 | 513.34 | 2,595.57 | 3,644.24 | 4,326.73 | 5,888.09 | 6,718.19 | ||||||||||

| NY,PA,OH,MI,IN,MD,DE,NJ,DC | 1,483.76 | 3,740.36 | 11,927.21 | 18,291.93 | 28,154.73 | 40,825.60 | |||||||||||

| VA,WV,KY,TN,MS,AL,GA,FL,NC,SC | 10.00 | 737.33 | 2,082.07 | 7,907.79 | 10,609.60 | 14,458.33 | 27,833.15 | ||||||||||

| IL,IA,WI,MO,MN | 46.48 | 4,951.47 | 11,030.85 | 22,212.98 | 35,579.80 | ||||||||||||

| LA,AR & OK (Indian) Territory | 20.75 | 107.00 | 250.23 | 331.23 | 1,621.11 | 5,153.91 | |||||||||||

| (Terr.)ND/SD,NM,WY,MT,ID,UT,AZ,WA (States)NE,KS,TX,CO,CA,NV,OR | 238.85 | 4,577.99 | 15,466.18 | 47,451.47 | |||||||||||||

| TOTAL USA | 39.80 | 2,755.18 | 8,571.48 | 28,919.79 | 49,168.33 | 87,801.42 | 163,562.12 | ||||||||||

In 1869, the symbolically important transcontinental railroad was completed in the United States with the driving of a golden spike (near the city of Ogden

Ogden, Utah

Ogden is a city in Weber County, Utah, United States. Ogden serves as the county seat of Weber County. The population was 82,825 according to the 2010 Census. The city served as a major railway hub through much of its history, and still handles a great deal of freight rail traffic which makes it a...

).

Electric railways revolutionize urban transport

Prior to the development of electric railways, most overland transport aside from the railways had consisted primarily of horse powered vehicles. Placing a horse car on rails had enabled a horse to move twice as many people, and so street railways were born. The world's first electric tram line opened in Lichterfelde near Berlin, Germany, in 1881. It was built by Werner von Siemens (see Gross-Lichterfelde TramwayGross-Lichterfelde Tramway

The Gross Lichterfelde Tramway was the world's first electric tramway. It was built by the Siemens & Halske company in Lichterfelde, a suburb of Berlin, and went in service on 16 May 1881....

). Seven years later, in January 1888, Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

served as American proving grounds for electric railways as Frank Sprague

Frank J. Sprague

Frank Julian Sprague was an American naval officer and inventor who contributed to the development of the electric motor, electric railways, and electric elevators...

built an electric streetcar system there. By the 1890s, electric power became practical and more widespread, allowing extensive underground railways. Large cities such as London, New York, and Paris built subway systems. When electric propulsion became practical, most street railways were electrified. These then became known as "streetcars," "trolleys," "trams" and "Strassenbahn." They can be found around the world.

In many countries, these electric street railways grew beyond the metropolitan areas to connect with other urban centers. In the USA, "electric interurban" railroad networks connected most urban areas in the states of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York. In Southern California, the Pacific Electric Railway

Pacific Electric Railway

The Pacific Electric Railway , also known as the Red Car system, was a mass transit system in Southern California using streetcars, light rail, and buses...

connected most cities in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, and the Inland Empire

Inland Empire (California)

The Inland Empire is a region in Southern California. The region sits directly east of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The Inland Empire most commonly is used in reference to the U.S. Census Bureau's federally-defined Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario metropolitan area, which covers more than...

. There were similar systems in Europe. One of the more notable rail systems connected every town and city in Belgium. One of the more notable tramway systems in Asia is the Hong Kong Tramways

Hong Kong Tramways

Hong Kong Tramways is a tram system in Hong Kong and one of the earliest forms of public transport in Hong Kong. Owned and operated by Veolia Transport, the tramway runs on Hong Kong Island between Shau Kei Wan and Kennedy Town, with a branch circulating Happy Valley...

, which started operation in 1904 and run exclusively on double-decker trams.

The remnants of these systems still exist, and in many places they have been modernized to become part of the urban "rapid transit" system in their respective areas. In the past thirty years increasing numbers of cities have restored electric rail service by building "light rail" systems to replace the tram system they removed during the mid-20th century.

Diesel power

Diesel-electric locomotives could be described as electric locomotives with an on-board generator powered by a diesel engine. The first diesel locomotives were low-powered machines, diesel-mechanical types used in switching yards. Diesel and electric locomotives are cleaner, more efficient, and require less maintenance than steam locomotives. They also required less specialized skills in operation and their introduction diminished the power of railway unions in the United States (one of the earliest countries to adopt diesel power on a wide scale). After working through technical difficulties in the early 1900s, diesel locomotives became mainstream after World War II. By the 1970s, diesel and electric power had replaced steam power on most of the world's railroads.In the 20th century, road transport

Road transport

Road transport or road transportation is transport on roads of passengers or goods. A hybrid of road transport and ship transport is the historic horse-drawn boat.-History:...

and air travel replaced railroads for most long-distance passenger travel in the United States, but railroads remain important for hauling freight in the United States, and for passenger transport in many other countries.

High-speed rail

Starting with the opening of the first ShinkansenShinkansen

The , also known as THE BULLET TRAIN, is a network of high-speed railway lines in Japan operated by four Japan Railways Group companies. Starting with the Tōkaidō Shinkansen in 1964, the network has expanded to currently consist of of lines with maximum speeds of , of Mini-shinkansen with a...

line between Tokyo and Osaka

Osaka