History of ferrous metallurgy

Encyclopedia

Prehistory

Prehistory is the span of time before recorded history. Prehistory can refer to the period of human existence before the availability of those written records with which recorded history begins. More broadly, it refers to all the time preceding human existence and the invention of writing...

. The earliest surviving iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

artifacts, from the 5th millennium BC in Iran

Iran

Iran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

and 2nd millennium BC in China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, were made from meteoritic

Meteorite

A meteorite is a natural object originating in outer space that survives impact with the Earth's surface. Meteorites can be big or small. Most meteorites derive from small astronomical objects called meteoroids, but they are also sometimes produced by impacts of asteroids...

iron-nickel

Nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with the chemical symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel belongs to the transition metals and is hard and ductile...

. It is not known when or where the smelting

Smelting

Smelting is a form of extractive metallurgy; its main use is to produce a metal from its ore. This includes iron extraction from iron ore, and copper extraction and other base metals from their ores...

of iron from ore

Ore

An ore is a type of rock that contains minerals with important elements including metals. The ores are extracted through mining; these are then refined to extract the valuable element....

s began, but by the end of the 2nd millennium BC iron was being produced from iron ores from China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

to Sub-Saharan Africa. The use of wrought iron

Wrought iron

thumb|The [[Eiffel tower]] is constructed from [[puddle iron]], a form of wrought ironWrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon...

was known in the 1st millennium BC. During the medieval period, means were found in Europe of producing wrought iron from cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

(in this context known as pig iron

Pig iron

Pig iron is the intermediate product of smelting iron ore with a high-carbon fuel such as coke, usually with limestone as a flux. Charcoal and anthracite have also been used as fuel...

) using finery forge

Finery forge

Iron tapped from the blast furnace is pig iron, and contains significant amounts of carbon and silicon. To produce malleable wrought iron, it needs to undergo a further process. In the early modern period, this was carried out in a finery forge....

s. For all these processes, charcoal

Charcoal

Charcoal is the dark grey residue consisting of carbon, and any remaining ash, obtained by removing water and other volatile constituents from animal and vegetation substances. Charcoal is usually produced by slow pyrolysis, the heating of wood or other substances in the absence of oxygen...

was required as fuel.

Steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

(with a smaller carbon content than pig iron but more than wrought iron) was first produced in antiquity. New methods of producing it by carburizing bars of iron in the cementation process

Cementation process

The cementation process is an obsolete technique for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcote Steel Furnace, built in 1720, is the earliest surviving example...

were devised in the 17th century AD. In the Industrial Revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

, new methods of producing bar iron without charcoal were devised and these were later applied to produce steel. In the late 1850s

1850s

- Wars :* Crimean war fought between Imperial Russia and an alliance consisting of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Second French Empire, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Ottoman Empire...

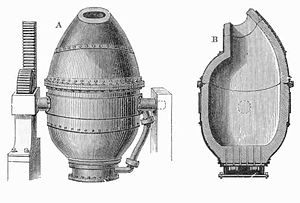

, Henry Bessemer

Henry Bessemer

Sir Henry Bessemer was an English engineer, inventor, and businessman. Bessemer's name is chiefly known in connection with the Bessemer process for the manufacture of steel.-Anthony Bessemer:...

invented a new steelmaking process

Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass-production of steel from molten pig iron. The process is named after its inventor, Henry Bessemer, who took out a patent on the process in 1855. The process was independently discovered in 1851 by William Kelly...

, involving blowing air through molten pig iron, to produce mild steel. This and other 19th century and later processes have led to wrought iron no longer being produced.

Hematitic and meteoric iron

Hematite

Hematite, also spelled as haematite, is the mineral form of iron oxide , one of several iron oxides. Hematite crystallizes in the rhombohedral system, and it has the same crystal structure as ilmenite and corundum...

, among the Khormusans of Egypt

Predynastic Egypt

The Prehistory of Egypt spans the period of earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt in ca. 3100 BC, starting with King Menes/Narmer....

, c. 35,000 BC.

Much later, metal was extracted from iron-nickel meteorites, which comprise about 6% of all meteorites that fall on the earth. That source can often be identified with certainty because of the unique crystalline

Crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions. The scientific study of crystals and crystal formation is known as crystallography...

features ("Widmanstatten figures") of that material, which are preserved when the metal is worked cold or at low temperature. Those artifacts include, for example, a bead

Bead

A bead is a small, decorative object that is usually pierced for threading or stringing. Beads range in size from under to over in diameter. A pair of beads made from Nassarius sea snail shells, approximately 100,000 years old, are thought to be the earliest known examples of jewellery. Beadwork...

from the 5th millennium BC found in Iran

Iran

Iran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

and spear tips and ornaments from Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

and Sumer

Sumer

Sumer was a civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age....

around 4000 BC. Meteoric iron has been identified also in a Chinese

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

axe head from the middle of the 2nd millennium BC.

These early uses appear to be largely ceremonial or ornamental. Meteoritic iron is very rare, and the metal was probably very expensive, perhaps more expensive than gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

. The early Hittites

Hittites

The Hittites were a Bronze Age people of Anatolia.They established a kingdom centered at Hattusa in north-central Anatolia c. the 18th century BC. The Hittite empire reached its height c...

are known to have barter

Barter

Barter is a method of exchange by which goods or services are directly exchanged for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. It is usually bilateral, but may be multilateral, and usually exists parallel to monetary systems in most developed countries, though to a...

ed iron (meteoritic or smelted) for silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

, at a rate of 40 times the iron's weight, with Assyria

Assyria

Assyria was a Semitic Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid–23rd century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia , that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur...

.

Meteoric iron was also fashioned into tools in precontact North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

. Beginning around the year 1000, the Thule people

Thule people

The Thule or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by AD 1000 and expanded eastwards across Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region...

of Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

began making harpoon

Harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument used in fishing to catch fish or large marine mammals such as whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal, allowing the fishermen to use a rope or chain attached to the butt of the projectile to catch the animal...

s, knives, ulo

Ülo

Ülo is an Estonian masculine given name.People named Ülo include:*Ülo Altermann , soldier and forest brother*Ülo Jõgi , war historian, nationalist and activist*Ülo Kaevats , statesman, academic, and philosopher...

s and other edged tools from pieces of the Cape York meteorite

Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite is named for Cape York, the location of its discovery in Savissivik, Greenland, and is one of the largest iron meteorites in the world.-History:The meteorite collided with Earth nearly 10,000 years ago...

. Typically pea-size bits of metal were cold-hammered into disks that were fitted into a bone handle. These artifacts were also used as trade goods with other Arctic peoples: tools made from the Cape York meteorite have been found in archaeological sites more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) away. When the American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

polar explorer Robert Peary

Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary, Sr. was an American explorer who claimed to have been the first person, on April 6, 1909, to reach the geographic North Pole...

shipped the largest piece of the meteorite to the American Museum of Natural History

American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History , located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City, United States, is one of the largest and most celebrated museums in the world...

in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

in 1897, it still weighed over 33 ton

Ton

The ton is a unit of measure. It has a long history and has acquired a number of meanings and uses over the years. It is used principally as a unit of weight, and as a unit of volume. It can also be used as a measure of energy, for truck classification, or as a colloquial term.It is derived from...

s. Another example of a late use of meteoritic iron is an adze

Adze

An adze is a tool used for smoothing or carving rough-cut wood in hand woodworking. Generally, the user stands astride a board or log and swings the adze downwards towards his feet, chipping off pieces of wood, moving backwards as they go and leaving a relatively smooth surface behind...

from around 1000 AD found in Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

.

Because meteorites fall from the sky, some linguists have conjectured that the English word iron (OE īsern), which has cognates in many northern and Western European languages, derives from the Etruscan

Etruscan language

The Etruscan language was spoken and written by the Etruscan civilization, in what is present-day Italy, in the ancient region of Etruria and in parts of Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna...

aisar which means "the gods". Even if this is not the case, the word is likely a loan into pre-Proto-Germanic from Celtic

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

or Italic

Italic languages

The Italic subfamily is a member of the Indo-European language family. It includes the Romance languages derived from Latin , and a number of extinct languages of the Italian Peninsula, including Umbrian, Oscan, Faliscan, and Latin.In the past various definitions of "Italic" have prevailed...

. Krahe compares Old Irish, Illyrian

Illyrian languages

The Illyrian languages are a group of Indo-European languages that were spoken in the western part of the Balkans in former times by groups identified as Illyrians: Ardiaei, Delmatae, Pannonii, Autariates, Taulanti...

, Venetic and Messapic forms).

Native iron

NativeNative Metal

A native metal is any metal that is found in its metallic form, either pure or as an alloy, in nature. Metals that can be found as native deposits singly and/or in alloys include aluminium, antimony, arsenic, bismuth, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, indium, iron, nickel, selenium, tantalum, tellurium,...

iron in the metallic state occurs rarely as small inclusions in certain basalt

Basalt

Basalt is a common extrusive volcanic rock. It is usually grey to black and fine-grained due to rapid cooling of lava at the surface of a planet. It may be porphyritic containing larger crystals in a fine matrix, or vesicular, or frothy scoria. Unweathered basalt is black or grey...

rocks. Besides meteoritic iron, Thule people of Greenland have used native iron from the Disko

Disko

Disko may refer to:*Disko Island or Qeqertarsuaq, in Baffin Bay, Greenland*Disko, Indiana, a small town in the United States*The character Disko Troop in the book Captains Courageous*Disk'O, a type of amusement ride manufactured by Zamperla...

region.

Iron smelting and the Iron Age

Iron smelting — the extraction of usable metal from oxidized iron ores — is more difficult than tinTin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

and copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

smelting. While these metals and their alloys can be cold-worked or melted in relatively simple furnaces (such as the kilns used for pottery

Pottery

Pottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

) and cast into molds, smelted iron requires hot-working and can be melted only in specially designed furnaces. Thus it is not surprising that humans only mastered the technology of smelted iron after several millennia of bronze metallurgy.

The place and time for the discovery of iron smelting is not known, partly because of the difficulty of distinguishing metal extracted from nickel-containing ores from hot-worked meteoritic iron. The archaeological evidence seems to point to the Middle East area, during the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

in the 3rd millennium BC. However iron artifacts remained a rarity until the 12th century BC.

The Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

is conventionally defined by the widespread use of steel weapons and tools, alongside or in replacement to bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

ones. That transition happened at different times in different places, as the technology spread through the Old World

Old World

The Old World consists of those parts of the world known to classical antiquity and the European Middle Ages. It is used in the context of, and contrast with, the "New World" ....

. Mesopotamia was fully into the Iron Age by 900 BC. Although Egypt produced iron artifacts, bronze remained dominant there until the conquest by Assyria in 663 BC. The Iron Age started in Central Europe around 500 BCE, and in India and China sometime between 1200 and 500 BC. Around 500 BCE, Nubia

Nubia

Nubia is a region along the Nile river, which is located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.There were a number of small Nubian kingdoms throughout the Middle Ages, the last of which collapsed in 1504, when Nubia became divided between Egypt and the Sennar sultanate resulting in the Arabization...

became a major manufacturer and exporter of iron. This was after being expelled from Egypt by Assyrians, who used iron weapons.

Ancient Near East

One of the earliest smelted iron artifacts known is a dagger with an iron blade found in a HattiHattians

The Hattians were an ancient people who inhabited the land of Hatti in present-day central part of Anatolia, Turkey, noted at least as early as the empire of Sargon of Akkad , until they were gradually displaced and absorbed ca...

c tomb in Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

, dating from 2500 BC. About 1500 BC, increasing numbers of non-meteoritic, smelted iron objects appear in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

, Anatolia, and Egypt. An iron dagger with golden hilt was found in the tomb

Tomb

A tomb is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes...

of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

ian ruler Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun , Egyptian , ; approx. 1341 BC – 1323 BC) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty , during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom...

, died in 1323 BC. An Ancient Egyptian sword

Sword

A sword is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. The precise definition of the term varies with the historical epoch or the geographical region under consideration...

bearing the name of pharaoh

Pharaoh

Pharaoh is a title used in many modern discussions of the ancient Egyptian rulers of all periods. The title originates in the term "pr-aa" which means "great house" and describes the royal palace...

Merneptah

Merneptah

Merneptah was the fourth ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. He ruled Egypt for almost ten years between late July or early August 1213 and May 2, 1203 BC, according to contemporary historical records...

as well as a battle axe

Battle axe

A battle axe is an axe specifically designed for combat. Battle axes were specialized versions of utility axes...

with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit

Ugarit

Ugarit was an ancient port city in the eastern Mediterranean at the Ras Shamra headland near Latakia, Syria. It is located near Minet el-Beida in northern Syria. It is some seven miles north of Laodicea ad Mare and approximately fifty miles east of Cyprus...

.

Although iron objects from the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

were found all across the Eastern Mediterranean, they are statistically insignificant compared to the quantity of bronze objects during this time. However, by the 12th century BC iron smelting and forging, for weapons and tools, was common from Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa as a geographical term refers to the area of the African continent which lies south of the Sahara. A political definition of Sub-Saharan Africa, instead, covers all African countries which are fully or partially located south of the Sahara...

through India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

. As the technology spread, iron came to replace bronze as the dominant metal used for tools and weapons across the Eastern Mediterranean (the Levant

Levant

The Levant or ) is the geographic region and culture zone of the "eastern Mediterranean littoral between Anatolia and Egypt" . The Levant includes most of modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories, and sometimes parts of Turkey and Iraq, and corresponds roughly to the...

, Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

, Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

, Anatolia, and Egypt).

Iron smelting was originally produced in bloomeries

Bloomery

A bloomery is a type of furnace once widely used for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. A bloomery's product is a porous mass of iron and slag called a bloom. This mix of slag and iron in the bloom is termed sponge iron, which...

, furnaces where bellows

Bellows

A bellows is a device for delivering pressurized air in a controlled quantity to a controlled location.Basically, a bellows is a deformable container which has an outlet nozzle. When the volume of the bellows is decreased, the air escapes through the outlet...

were used to force air through a pile of iron ore and burning charcoal

Charcoal

Charcoal is the dark grey residue consisting of carbon, and any remaining ash, obtained by removing water and other volatile constituents from animal and vegetation substances. Charcoal is usually produced by slow pyrolysis, the heating of wood or other substances in the absence of oxygen...

. The carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide , also called carbonous oxide, is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas that is slightly lighter than air. It is highly toxic to humans and animals in higher quantities, although it is also produced in normal animal metabolism in low quantities, and is thought to have some normal...

produced by the charcoal reduced the iron oxide

Iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. All together, there are sixteen known iron oxides and oxyhydroxides.Iron oxides and oxide-hydroxides are widespread in nature, play an important role in many geological and biological processes, and are widely utilized by humans, e.g.,...

from the ore to metallic iron. However, the bloomery was not hot enough to melt the iron, so the metal collected in the bottom of the furnace as a spongy mass, or "bloom", whose pores were filled with ash

Wood ash

Wood ash is the residue powder left after the combustion of wood. Main producers of wood ash are wood industries and power plants.-Composition:...

and slag

Slag

Slag is a partially vitreous by-product of smelting ore to separate the metal fraction from the unwanted fraction. It can usually be considered to be a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. However, slags can contain metal sulfides and metal atoms in the elemental form...

. The bloom then had to be reheated to soften the iron and melt the slag, and then repeatedly beaten and folded to force the molten slag out of it. The result of this time-consuming and laborious process was wrought iron

Wrought iron

thumb|The [[Eiffel tower]] is constructed from [[puddle iron]], a form of wrought ironWrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon...

, a malleable but fairly soft alloy.

Concurrent with the transition from bronze to iron was the discovery of carburization

Carburization

Carburizing, spelled carburising in the UK, is a heat treatment process in which iron or steel is heated in the presence of another material which liberates carbon as it decomposes. Depending on the amount of time and temperature, the affected area can vary in carbon content...

, the process of adding carbon to wrought iron. While the iron bloom contained some carbon, the subsequent hot-working oxidized most of it. Smiths in the Middle East discovered that wrought iron could be turned into a much harder product by heating the shaped piece in a bed of charcoal for some time, and then quench

Quench

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece to obtain certain material properties. It prevents low-temperature processes, such as phase transformations, from occurring by only providing a narrow window of time in which the reaction is both thermodynamically favorable and...

ing it in water or oil. This procedure turned the outer layers of the piece into steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

, an alloy of iron and iron carbides, which was harder and less brittle than the bronze it began to replace.

Theories on the origin of iron smelting

The development of iron smelting was traditionally attributed to the HittitesHittites

The Hittites were a Bronze Age people of Anatolia.They established a kingdom centered at Hattusa in north-central Anatolia c. the 18th century BC. The Hittite empire reached its height c...

of Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

. It was believed that they maintained a monopoly on ironworking, and that their empire had been based on that advantage. According to that theory, the ancient Sea Peoples

Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a confederacy of seafaring raiders of the second millennium BC who sailed into the eastern Mediterranean, caused political unrest, and attempted to enter or control Egyptian territory during the late 19th dynasty and especially during year 8 of Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty...

, who invaded the Eastern Mediterranean and destroyed the Hittite empire at the end of the Late Bronze Age, were responsible for spreading the knowledge through that region. This theory is no longer held in the mainstream of scholarship, since there is no archaeological evidence of the alleged Hittite monopoly. While there are some iron objects from Bronze Age Anatolia, the number is comparable to iron objects found in Egypt and other places of the same time period; and only a small number of these objects are weapons.

A more recent theory claims that the development of iron technology was driven by the disruption of the copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

and tin

Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

trade routes, due to the collapse of the empires at the end of the Late Bronze Age. These metals, especially tin, were not widely available and needed to be transported over long distances; whereas iron ores are widely available. However, there is no archaeological evidence that would suggest a shortage of bronze or tin in the Early Iron Age. Bronze objects continued to be abundant, and these objects have the same percentage of tin as those from the Late Bronze Age.

Indian Sub-Continent

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh abbreviation U.P. , is a state located in the northern part of India. With a population of over 200 million people, it is India's most populous state, as well as the world's most populous sub-national entity...

have yielded iron implements dated between 1800 BC - 1200 BC . Some scholars believe that by the early 13th century BC

13th century BC

The 13th century BC was the period from 1300 to 1201 BC.-Events:*1300 BC: Cemetery H culture comes to an end.*1292 BC: End of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, start of the Nineteenth Dynasty....

iron smelting was practiced in a large scale in India. In Southern India (present day Mysore) iron appeared as early as 11th

11th century BC

The 11th century BC comprises all years from 1100 BC to 1001 BC. Although many human societies were literate in this period, some of the individuals mentioned below may be considered legendary rather than fully historical.-Events:...

to 12th centuries BC. The technology of iron metallurgy advanced during a period of peaceful settlements in the 1st millennium BC. and the politically stable Maurya

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in ancient India, ruled by the Mauryan dynasty from 321 to 185 BC...

period.

Iron artifacts such as spikes, knives

Knife

A knife is a cutting tool with an exposed cutting edge or blade, hand-held or otherwise, with or without a handle. Knives were used at least two-and-a-half million years ago, as evidenced by the Oldowan tools...

, dagger

Dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a sharp point designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon. The design dates to human prehistory, and daggers have been used throughout human experience to the modern day in close combat confrontations...

s, arrow

Arrow

An arrow is a shafted projectile that is shot with a bow. It predates recorded history and is common to most cultures.An arrow usually consists of a shaft with an arrowhead attached to the front end, with fletchings and a nock at the other.- History:...

-heads, bowls

Bowl (vessel)

A bowl is a common open-top container used in many cultures to serve food, and is also used for drinking and storing other items. They are typically small and shallow, although some, such as punch bowls and salad bowls, are larger and often intended to serve many people.Bowls have existed for...

, spoon

Spoon

A spoon is a utensil consisting of a small shallow bowl, oval or round, at the end of a handle. A type of cutlery , especially as part of a place setting, it is used primarily for serving. Spoons are also used in food preparation to measure, mix, stir and toss ingredients...

s, saucepans, axe

Axe

The axe, or ax, is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood; to harvest timber; as a weapon; and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol...

s, chisel

Chisel

A chisel is a tool with a characteristically shaped cutting edge of blade on its end, for carving or cutting a hard material such as wood, stone, or metal. The handle and blade of some types of chisel are made of metal or wood with a sharp edge in it.In use, the chisel is forced into the material...

s, tong

Tong

-Chinese:*Tang Dynasty, a dynasty in Chinese history when transliterated from Cantonese*Tong , a type of social organization found in Chinese immigrant communities*tong, pronunciation of several Chinese characters*See:...

s, door fittings etc. ranging from 600 to 200 BC have been discovered from several archaeological sites of India. The Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

wrote the first western

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

account of the use of iron in India. The Indian mythological texts, the Upnishads, have mentions of weaving, pottery, and metallurgy as well. The Romans

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

had high regard for the chemical excellence of cast iron from India in the time of the Gupta Empire

Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed approximately from 320 to 550 CE and covered much of the Indian Subcontinent. Founded by Maharaja Sri-Gupta, the dynasty was the model of a classical civilization. The peace and prosperity created under leadership of Guptas enabled the...

.

Crucible steel

Crucible steel describes a number of different techniques for making steel in a crucible. Its manufacture is essentially a refining process which is dependent on preexisting furnace products...

. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon. Iron chain was used in Indian suspension bridge

Suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck is hung below suspension cables on vertical suspenders. Outside Tibet and Bhutan, where the first examples of this type of bridge were built in the 15th century, this type of bridge dates from the early 19th century...

s as early as the 4th century.

Wootz steel

Wootz steel

Wootz steel is a steel characterized by a pattern of bands or sheets of micro carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix. It was developed in India around 300 BCE...

was produced in India and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is a country off the southern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Known until 1972 as Ceylon , Sri Lanka is an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait, and lies in the vicinity of India and the...

from around 300 BC. Wootz steel was famous since Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

for its durability and ability to hold an edge. When asked by Alexander to select a gift, King Porus is said to have chosen, instead of gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

or silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

, thirty pounds of steel. Wootz steel was originally a complex alloy with iron as its main component together with various trace element

Trace element

In analytical chemistry, a trace element is an element in a sample that has an average concentration of less than 100 parts per million measured in atomic count, or less than 100 micrograms per gram....

s. Recent studies have suggested that its qualities may have been due to the formation of carbon nanotubes in the metal. According to Will Durant

Will Durant

William James Durant was a prolific American writer, historian, and philosopher. He is best known for The Story of Civilization, 11 volumes written in collaboration with his wife Ariel Durant and published between 1935 and 1975...

,the technology passed to the Persians

Persian people

The Persian people are part of the Iranian peoples who speak the modern Persian language and closely akin Iranian dialects and languages. The origin of the ethnic Iranian/Persian peoples are traced to the Ancient Iranian peoples, who were part of the ancient Indo-Iranians and themselves part of...

and from them to Arab

Arab

Arab people, also known as Arabs , are a panethnicity primarily living in the Arab world, which is located in Western Asia and North Africa. They are identified as such on one or more of genealogical, linguistic, or cultural grounds, with tribal affiliations, and intra-tribal relationships playing...

s who spread it through the Middle East. In the 16th century the Dutch

Dutch Empire

The Dutch Empire consisted of the overseas territories controlled by the Dutch Republic and later, the modern Netherlands from the 17th to the 20th century. The Dutch followed Portugal and Spain in establishing an overseas colonial empire, but based on military conquest of already-existing...

carried the technology from South India to Europe, where it came to be mass produced.

Steel was being produced in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is a country off the southern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Known until 1972 as Ceylon , Sri Lanka is an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait, and lies in the vicinity of India and the...

since 300 BC by furnaces blown by the monsoon winds. The furnaces were dug into the crests of hills, and the wind was diverted into the air vents by long trenches. This arrangement created a zone of high pressure at the entrance and a zone of low pressure at the top of the furnace. The flow is believed to have allowed higher temperatures than those which were possible with bellows-driven furnaces, resulting in better-quality iron. Steel made in Sri Lanka were traded extensively within the region and in the Islamic world.

One of the world's foremost metallurgical curiosities is an iron pillar located in the Qutb complex

Qutb complex

The Qutb complex , also spelled Qutab or Qutub, is an array of monuments and buildings at Mehrauli in Delhi, India. The construction of Qutb Minar was intended as a Victory Tower, to celebrate the victory of Mohammed Ghori over Rajput king, Prithviraj Chauhan, in 1192 AD, by his then viceroy,...

, Delhi

Delhi

Delhi , officially National Capital Territory of Delhi , is the largest metropolis by area and the second-largest by population in India, next to Mumbai. It is the eighth largest metropolis in the world by population with 16,753,265 inhabitants in the Territory at the 2011 Census...

. The pillar is made of wrought iron (98% Fe

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

), is almost seven meters high and weights more than six tonnes. The pillar was erected by Chandragupta II

Chandragupta II

Chandragupta II the Great, very often referred to as Vikramaditya or Chandragupta Vikramaditya in Sanskrit; was one of the most powerful emperors of the Gupta empire in northern India. His rule spanned c...

Vikramaditya and has withstood 1,600 years of exposure to heavy rains with relatively little corrosion

Corrosion

Corrosion is the disintegration of an engineered material into its constituent atoms due to chemical reactions with its surroundings. In the most common use of the word, this means electrochemical oxidation of metals in reaction with an oxidant such as oxygen...

.

Iron Age Europe

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

in the late 11th century BC. The earliest marks of Iron Age in Central Europe are artifacts from the Hallstatt C culture (8th century BC

8th century BC

The 8th century BC started the first day of 800 BC and ended the last day of 701 BC.-Overview:The 8th century BC was a period of great changes in civilizations. In Egypt, the 23rd and 24th dynasties led to rule from Nubia in the 25th Dynasty...

). Throughout the 7th to 6th centuries BC, iron artifacts remained luxury items reserved for an elite. This changes dramatically shortly after 500 BC with the rise of the La Tène culture

La Tène culture

The La Tène culture was a European Iron Age culture named after the archaeological site of La Tène on the north side of Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland, where a rich cache of artifacts was discovered by Hansli Kopp in 1857....

, from which time iron metallurgy also becomes common in Northern Europe and Britain. The spread of ironworking in Central and Western Europe is associated with Celtic expansion. By the 1st century BC, Noric steel

Noric steel

Noric steel was a famously high quality steel from Noricum during the time of the Roman Empire.The proverbial hardness of Noric steel is expressed by Ovid: "...durior [...] ferro quod noricus excoquit ignis..." and it was largely used for the weapons of the Roman military.The iron ore was...

was famous for its quality and sought-after by the Roman military.

The annual iron output of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

is estimated at 84,750 t, while the similarly populous Han China produced around 5,000 t.

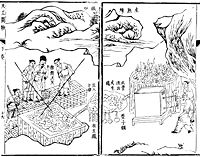

China

Casting

In metalworking, casting involves pouring liquid metal into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowing it to cool and solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or broken out of the mold to complete the process...

into molds

Molding (process)

Molding or moulding is the process of manufacturing by shaping pliable raw material using a rigid frame or model called a pattern....

, a method far less laborious than individually forging each piece of iron from a bloom. This technology would be known in Europe from early medieval times on.

Cast iron is rather brittle and unsuitable for striking implements. It can, however, be decarburized to steel or wrought iron by heating it in air for several days. In China, these ironworking methods spread northward, and by 300 BC, iron was the material of choice throughout China for most tools and weapons. A mass grave in Hebei

Hebei

' is a province of the People's Republic of China in the North China region. Its one-character abbreviation is "" , named after Ji Province, a Han Dynasty province that included what is now southern Hebei...

province, dated to the early third century BC, contains several soldiers buried with their weapons and other equipment. The artifacts recovered from this grave are variously made of wrought iron, cast iron, malleabilized cast iron, and quench-hardened steel, with only a few, probably ornamental, bronze weapons.

Han Dynasty

The Han Dynasty was the second imperial dynasty of China, preceded by the Qin Dynasty and succeeded by the Three Kingdoms . It was founded by the rebel leader Liu Bang, known posthumously as Emperor Gaozu of Han. It was briefly interrupted by the Xin Dynasty of the former regent Wang Mang...

(202 BC

202 BC

Year 202 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Geminus and Nero...

–AD 220

220

Year 220 was a leap year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Antonius and Eutychianus...

), the government established ironworking as a state monopoly (yet repealed during the latter half of the dynasty, returned to private entrepreneurship) and built a series of large blast furnaces in Henan

Henan

Henan , is a province of the People's Republic of China, located in the central part of the country. Its one-character abbreviation is "豫" , named after Yuzhou , a Han Dynasty state that included parts of Henan...

province, each capable of producing several tons of iron per day. By this time, Chinese metallurgists had discovered how to fine molten pig iron, stirring it in the open air until it lost its carbon and became wrought iron. (In modern Mandarin-Chinese

Chinese language

The Chinese language is a language or language family consisting of varieties which are mutually intelligible to varying degrees. Originally the indigenous languages spoken by the Han Chinese in China, it forms one of the branches of Sino-Tibetan family of languages...

, this process is now called chao, literally, stir frying

Stir frying

Stir frying is an umbrella term used to describe two Chinese cooking techniques for preparing food in a wok: chǎo and bào . The term stir-fry was introduced into the English language by Buwei Yang Chao, in her book How to Cook and Eat in Chinese, to describe the chǎo technique...

.) By the 1st century BC, Chinese metallurgists had found that wrought iron and cast iron could be melted together to yield an alloy of intermediate carbon content, that is, steel. According to legend, the sword of Liu Bang, the first Han emperor, was made in this fashion. Some texts of the era mention "harmonizing the hard and the soft" in the context of ironworking; the phrase may refer to this process. Also, the ancient city of Wan (Nanyang

Nanyang, Henan

Nanyang is a prefecture-level city in the southwest of Henan province, People's Republic of China. The city with the largest administrative area in Henan, Nanyang borders Xinyang to the southeast, Zhumadian to the east, Pingdingshan to the northeast, Luoyang to the north, Sanmenxia to the...

) from the Han period forward was a major center of the iron and steel industry. Along with their original methods of forging steel, the Chinese had also adopted the production methods of creating Wootz steel, an idea imported from India to China by the 5th century AD. The Chinese during the ancient Han Dynasty were also the first to apply hydraulic power (i.e. a waterwheel) in working the inflatable bellows of the blast furnace. This was recorded in the year 31 AD, an innovation of the engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

Du Shi

Du Shi

Du Shi was a Chinese governmental Prefect of Nanyang in 31 AD and a mechanical engineer of the Eastern Han Dynasty in ancient China. Du Shi is credited with being the first to apply hydraulic power to operate bellows in metallurgy...

, Prefect

Prefect

Prefect is a magisterial title of varying definition....

of Nanyang. Although Du Shi was the first to apply water power to bellows in metallurgy, the first drawn and printed illustration of its operation with water power came in 1313 AD, in the Yuan Dynasty era text called the Nong Shu. In the 11th century, there is evidence of the production of steel in Song China

Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was a ruling dynasty in China between 960 and 1279; it succeeded the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, and was followed by the Yuan Dynasty. It was the first government in world history to issue banknotes or paper money, and the first Chinese government to establish a...

using two techniques: a "berganesque" method that produced inferior, heterogeneous steel and a precursor to the modern Bessemer process that utilized partial decarbonization via repeated forging under a cold blast. By the 11th century, there was also a large amount of deforestation in China due to the iron industry's demands for charcoal. However, by this time the Chinese had figured out how to use bituminous coke

Coke (fuel)

Coke is the solid carbonaceous material derived from destructive distillation of low-ash, low-sulfur bituminous coal. Cokes from coal are grey, hard, and porous. While coke can be formed naturally, the commonly used form is man-made.- History :...

to replace the use of charcoal, and with this switch in resources many acres of prime timberland in China were spared. This switch in resources from charcoal to coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

was pioneered in Roman Britain

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

by the 2nd century AD, although it was also practised in the continental Rhineland

Rhineland

Historically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

at the time.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Inhabitants at Termit, in eastern Niger

Niger

Niger , officially named the Republic of Niger, is a landlocked country in Western Africa, named after the Niger River. It borders Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north and Chad to the east...

became the first iron smelting people in West Africa and among the first in the world around 1500 BC. Iron and copper working then continued to spread southward through the continent, reaching the Cape

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

around AD 200. The widespread use of iron revolutionized the Bantu

Bantu languages

The Bantu languages constitute a traditional sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages. There are about 250 Bantu languages by the criterion of mutual intelligibility, though the distinction between language and dialect is often unclear, and Ethnologue counts 535 languages...

-speaking farming communities who adopted it, driving out and absorbing the rock tool using hunter-gatherer societies they encountered as they expanded to farm wider areas of savanna

Savanna

A savanna, or savannah, is a grassland ecosystem characterized by the trees being sufficiently small or widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to support an unbroken herbaceous layer consisting primarily of C4 grasses.Some...

h. The technologically superior Bantu-speakers spread across southern Africa and became wealthy and powerful, producing iron for tools and weapons in large, industrial quantities.

In the region of the Aïr Mountains

Aïr Mountains

The Aïr Mountains is a triangular massif, located in northern Niger, within the Sahara desert...

in Niger

Niger

Niger , officially named the Republic of Niger, is a landlocked country in Western Africa, named after the Niger River. It borders Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north and Chad to the east...

we have the development of independent copper smelting between 3000–2500 BC. The process was not in a developed state, indication smelting was not foreign. It became mature about the 1500 BC.

Medieval Islamic world

Iron technology was further advanced by several inventions in medieval Islam, during the so-called Islamic Golden AgeIslamic Golden Age

During the Islamic Golden Age philosophers, scientists and engineers of the Islamic world contributed enormously to technology and culture, both by preserving earlier traditions and by adding their own inventions and innovations...

. These included a variety of water-powered

Watermill

A watermill is a structure that uses a water wheel or turbine to drive a mechanical process such as flour, lumber or textile production, or metal shaping .- History :...

and wind-powered

Windmill

A windmill is a machine which converts the energy of wind into rotational energy by means of vanes called sails or blades. Originally windmills were developed for milling grain for food production. In the course of history the windmill was adapted to many other industrial uses. An important...

industrial mills for metal production, including geared gristmill

Gristmill

The terms gristmill or grist mill can refer either to a building in which grain is ground into flour, or to the grinding mechanism itself.- Early history :...

s and forge

Forge

A forge is a hearth used for forging. The term "forge" can also refer to the workplace of a smith or a blacksmith, although the term smithy is then more commonly used.The basic smithy contains a forge, also known as a hearth, for heating metals...

s. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Muslim world

Muslim world

The term Muslim world has several meanings. In a religious sense, it refers to those who adhere to the teachings of Islam, referred to as Muslims. In a cultural sense, it refers to Islamic civilization, inclusive of non-Muslims living in that civilization...

had these industrial mills in operation, from Islamic Spain

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

and North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

in the west to the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

and Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

in the east. There are also 10th-century references to cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

, as well as archeological evidence of blast furnace

Blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally iron.In a blast furnace, fuel and ore and flux are continuously supplied through the top of the furnace, while air is blown into the bottom of the chamber, so that the chemical reactions...

s being used in the Ayyubid and Mamluk

Mamluk

A Mamluk was a soldier of slave origin, who were predominantly Cumans/Kipchaks The "mamluk phenomenon", as David Ayalon dubbed the creation of the specific warrior...

empires from the 11th century, thus suggesting a diffusion of Chinese metal technology to the Islamic world.

Gear

Gear

A gear is a rotating machine part having cut teeth, or cogs, which mesh with another toothed part in order to transmit torque. Two or more gears working in tandem are called a transmission and can produce a mechanical advantage through a gear ratio and thus may be considered a simple machine....

ed gristmills were invented by Muslim engineers, and were used for crushing metallic ores before extraction. Gristmills in the Islamic world were often made from both watermill

Watermill

A watermill is a structure that uses a water wheel or turbine to drive a mechanical process such as flour, lumber or textile production, or metal shaping .- History :...

s and windmills. In order to adapt water wheel

Water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of free-flowing or falling water into useful forms of power. A water wheel consists of a large wooden or metal wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving surface...

s for gristmilling purposes, cam

Cam

A cam is a rotating or sliding piece in a mechanical linkage used especially in transforming rotary motion into linear motion or vice-versa. It is often a part of a rotating wheel or shaft that strikes a lever at one or more points on its circular path...

s were used for raising and releasing trip hammer

Trip hammer

A trip hammer, also known as a helve hammer, is a massive powered hammer used in:* agriculture to facilitate the labor of pounding, decorticating and polishing of grain;...

s to fall on a material. The first forge

Forge

A forge is a hearth used for forging. The term "forge" can also refer to the workplace of a smith or a blacksmith, although the term smithy is then more commonly used.The basic smithy contains a forge, also known as a hearth, for heating metals...

to be driven by a hydropower

Hydropower

Hydropower, hydraulic power, hydrokinetic power or water power is power that is derived from the force or energy of falling water, which may be harnessed for useful purposes. Since ancient times, hydropower has been used for irrigation and the operation of various mechanical devices, such as...

ed water mill rather than manual labour was invented in the 12th century Islamic Spain.

One of the most famous steels produced in the medieval Near East was Damascus steel

Damascus steel

Damascus steel was a term used by several Western cultures from the Medieval period onward to describe a type of steel used in swordmaking from about 300 BCE to 1700 CE. These swords are characterized by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water...

used for swordmaking, and mostly produced in Damascus

Damascus

Damascus , commonly known in Syria as Al Sham , and as the City of Jasmine , is the capital and the second largest city of Syria after Aleppo, both are part of the country's 14 governorates. In addition to being one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Damascus is a major...

, Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

, in the period from 900 to 1750. This was produced using the crucible steel

Crucible steel

Crucible steel describes a number of different techniques for making steel in a crucible. Its manufacture is essentially a refining process which is dependent on preexisting furnace products...

method, based on the earlier Indian wootz steel

Wootz steel

Wootz steel is a steel characterized by a pattern of bands or sheets of micro carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix. It was developed in India around 300 BCE...

. This process was adopted in the Middle East using locally produced steels. The exact process remains unknown, but allowed carbide

Carbide

In chemistry, a carbide is a compound composed of carbon and a less electronegative element. Carbides can be generally classified by chemical bonding type as follows: salt-like, covalent compounds, interstitial compounds, and "intermediate" transition metal carbides...

s to precipitate out as micro particles arranged in sheets or bands within the body of a blade. The carbides are far harder than the surrounding low carbon steel, allowing the swordsmith to make an edge which would cut hard materials with the precipitated carbides, while the bands of softer steel allowed the sword as a whole to remain tough and flexible. A team of researchers based at the Technical University of Dresden

Dresden

Dresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

that uses x-ray

X-ray

X-radiation is a form of electromagnetic radiation. X-rays have a wavelength in the range of 0.01 to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30 petahertz to 30 exahertz and energies in the range 120 eV to 120 keV. They are shorter in wavelength than UV rays and longer than gamma...

s and electron microscopy to examine Damascus steel discovered the presence of cementite

Cementite

Cementite, also known as iron carbide, is a chemical compound of iron and carbon, with the formula Fe3C . By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, brittle material, normally classified as a ceramic in its pure form, though it is more...

nanowires and carbon nanotube

Carbon nanotube

Carbon nanotubes are allotropes of carbon with a cylindrical nanostructure. Nanotubes have been constructed with length-to-diameter ratio of up to 132,000,000:1, significantly larger than for any other material...

s. Peter Paufler, a member of the Dresden team, says that these nanostructures give Damascus steel its distinctive properties and are a result of the forging

Forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which it is performed: '"cold," "warm," or "hot" forging. Forged parts can range in weight from less than a kilogram to 580 metric tons...

process.

Medieval and Early Modern Europe

There was no fundamental change in the technology of iron production in Europe for many centuries. Iron continued to be made in bloomeries. However there were two separate developments in the Medieval period. One was the application of water power to the bloomery process in various places (as outlined above). The other was the first European production in cast iron.Powered bloomeries

Sometime in the medieval period, water power was applied to the bloomery process. It is possible that this was at the Cistercian Abbey of ClairvauxClairvaux

Clairvaux can mean the following:*Clairvaux, a former commune in France, now part of Ville-sous-la-Ferté. It is the home of**Clairvaux Abbey in France**Clairvaux Prison, France, on the site of the abbey*Saint Bernard of Clairvaux...

as early as 1135, but it was certainly in use in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

by the early 13th century there and in Sweden. In England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, the first clear documentary evidence for this is the accounts of a forge of the Bishop of Durham, near Bedburn

Bedburn

Bedburn is a village in County Durham, in England. It is situated near Hamsterley and Hamsterley Forest, and the River Wear.-External links:...

in 1408, but that was certainly not the first such ironworks. In the Furness

Furness

Furness is a peninsula in south Cumbria, England. At its widest extent, it is considered to cover the whole of North Lonsdale, that part of the Lonsdale hundred that is an exclave of the historic county of Lancashire, lying to the north of Morecambe Bay....

district of England, powered bloomeries were in use into the beginning of the 18th century, and near Garstang

Garstang

Garstang is a town and civil parish within the Wyre borough of Lancashire, England. It is ten miles north-northwest of the city of Preston and eleven miles south of Lancaster, and had a total resident population of 4,074 in 2001....

until about 1770.

The Catalan Forge was a variety of powered bloomery. Bloomeries with hot blast

Hot blast

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. This has the result of considerably reducing the fuel consumed in the process...

were used in upstate New York in the mid 19th century.

Blast furnace

Cast iron development lagged in Europe, as the smelters could only achieve temperatures of about 1000 C; or perhaps they did not want hotter temperatures, as they were seeking to produce bloom

Bloom

Bloom or blooming may refer to:-Science and nature:* Bloom, one or more flowers on a flowering plant* Algal bloom, a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in an aquatic system...

s as a precursor of wrought iron, not cast iron. Through a good portion of the Middle Ages, in Western Europe, iron was thus still being made by the working of iron blooms into wrought iron. Some of the earliest casting of iron in Europe occurred in Sweden, in two sites, Lapphyttan

Lapphyttan

Lapphyttan in Norberg Municipality, Sweden, may be regarded as the type site for the Medieval Blast Furnace. Its date is probably between 1150 and 1350. It produced cast iron, which was then fined to make balls of iron known as osmonds. Osmonds occur in English Customs records in the 1250s and...

and Vinarhyttan, between 1150 and 1350 AD. Some scholars have speculated the practice followed the Mongols across Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

to these sites, but there is no clear proof of this hypothesis, and it would certainly not explain the pre-Mongol datings of many of these iron-production centres. In any event, by the late 14th century, a market for cast iron goods began to form, as a demand developed for cast iron cannonballs.

Osmond process

Iron from furnaces such as Lapphyttan was refined into wrought iron by the osmond processOsmond iron

Osmond iron was wrought iron made by a particular process. This is associated with the first European production of cast iron in furnaces such as Lapphyttan in Sweden....

. The pig iron from the furnace was melted in front of a blast of air and the droplets caught on a staff (which was spun). This formed a ball of iron, known as an osmond. This was probably a traded commodity by c. 1200.

Finery process

An alternative method of decarburising pig iron was the finery processFinery forge

Iron tapped from the blast furnace is pig iron, and contains significant amounts of carbon and silicon. To produce malleable wrought iron, it needs to undergo a further process. In the early modern period, this was carried out in a finery forge....

, which seems to have been devised in the region around Namur

Namur (city)

Namur is a city and municipality in Wallonia, in southern Belgium. It is both the capital of the province of Namur and of Wallonia....

in the 15th century. By the end of that century, this Walloon process spread to the Pay de Bray on the eastern boundary of Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

, and then to England, where it became the main method of making wrought iron by 1600. It was introduced to Sweden by Louis de Geer

Louis De Geer

Louis De Geer may refer to:People:*Louis De Geer , industrial entrepreneur of Walloon origin*Louis De Geer , industrial entrepreneur*Louis Gerhard De Geer , baron, Prime Minister of Sweden 1876–80...

in the early 17th century and was used to make the oregrounds iron

Oregrounds iron

Oregrounds iron was a grade of iron that was regarded as the best grade available in 18th century England. The term was derived from the small Swedish city of Öregrund. The process to create it is known as the Walloon method....

favoured by English steelmakers.

A variation on this was the German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

process. This became the main method of producing bar iron in Sweden.

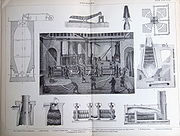

Cementation steel

In the early 17th century, ironworkers in Western Europe had developed the cementation processCementation process

The cementation process is an obsolete technique for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcote Steel Furnace, built in 1720, is the earliest surviving example...

for carburizing wrought iron. Wrought iron bars and charcoal were packed into stone boxes, then held at a red heat for up to a week. During this time, carbon diffused into the iron, producing a product called cement steel or blister steel. One of the earliest places where this was used in England was at Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides...

, where Sir Basil Brooke had two cementation furnaces (recently excavated). For a time in the 1610s, he owned a patent on the process, but had to surrender this in 1619. He probably used Forest of Dean

Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. The forest is a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and north, the River Severn to the south, and the City of Gloucester to the east.The...

iron as his raw material, but it was soon found that oregrounds iron was more suitable. The quality of the steel could be improved by faggoting

Faggoting (metalworking)