History of Zionism

Encyclopedia

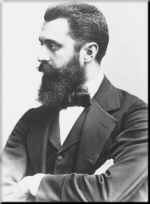

Zionism as an organized movement is generally considered to have been fathered by Theodor Herzl

in 1897; however the history of Zionism began earlier and related to Judaism

and Jewish history

. The Hovevei Zion

, or the Lovers of Zion, were responsible for the creation of 20 new Jewish settlements in Palestine between 1870 and 1897.

Before the Holocaust

the movement's central aims were the creation of a Jewish National Home and cultural centre in Palestine by facilitating Jewish migration

. After the Holocaust, the movement focussed on creation of a "Jewish state

" (usually defined as a secular state with a Jewish majority), attaining its goal in 1948 with the creation of Israel

.

Since the creation of Israel, the importance of the Zionist movement as an organization has declined, as the Israeli state has grown stronger.

The Zionist movement continues to exist, working to support Israel, assist persecuted Jews and encourage Jewish emigration to Israel

. While most Israeli political parties continue to define themselves as Zionist, modern Israeli political thought is no longer formulated within the Zionist movement.

The success of Zionism has meant that the percentage of the world's Jewish population

who live in Israel has steadily grown over the years and today 40% of the world's Jews live in Israel. There is no other example in human history of a "nation

" being restored after such a long period of existence as a Diaspora

.

, and thus later adopted in the Christian

Old Testament

. After Jacob

and his sons had gone down to Egypt to escape a drought, they were enslaved and became a nation. Later, as commanded by God, Moses

went before Pharaoh, demanded, "Let my people go!", and foretold severe consequences

, if this was not done. Most of the Torah is devoted to the story of the plagues and the Exodus

from Egypt, which is estimated at about 1400 BCE. These are celebrated annually during Passover

, and the Passover meal traditionally ends with the words "Next Year in Jerusalem."

The theme of return to their traditional homeland came up again after the Babylon

ians conquered Judea in 641 BCE and the Judeans were exiled to Babylon. In the book of Psalms

(Psalm 137

), Jews lamented their exile while Prophets like Ezekiel

foresaw their return. The Bible recounts how, in 538 BCE Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon and issued a proclamation

granting the people of Judah their freedom. 50,000 Judeans, led by Zerubbabel

returned. A second group of 5000, led by Ezra

and Nehemiah

, returned to Judea

in 456 BCE.

led a Jewish uprising in Kurdistan which aimed to reconquer the promised land. In 1648 Sabbatai Zevi

from modern Turkey claimed he would lead the Jews back to Israel. In 1868 Judah ben Shalom

led a large movement of Yemenite Jews

to Israel. A dispatch from the British Consulate in Jerusalem in 1839 reported that "the Jews of Algiers and its dependencies, are numerous in Palestine. . . ." There was also significant migration from Central Asia (Bukharan Jews

).

In addition to Messianic movements, the population of the Holy Land was slowly bolstered by Jews fleeing Christian persecution

especially after the Reconquista

of Al-Andalus

(the Muslim name of the Iberian Peninsula

). Safed became an important center of Kabbalah

. Jerusalem, Hebron

and Tiberias also had significant Jewish populations.

Eretz Israel was revered in a religious sense. They thought of a return to it in a future messianic age. Return remained a recurring theme among generations, particularly in Passover

and Yom Kippur

prayers which traditionally concluded with, "Next year in Jerusalem", and in the thrice-daily Amidah

(Standing prayer).

Jewish daily prayers include many references to "your people Israel", "your return to Jerusalem" and associate salvation with a restored presence in Israel and Jerusalem (usually accompanied by a Messiah); for example the prayer Uva Letzion

(Isiah 59"20): "And a redeemer shall come to Zion..." Aliyah (immigration to Israel) has always been considered a praiseworthy act for Jews according to Jewish law

and some Rabbis consider it one of the core 613 commandments

in Judaism. From the Middle Ages

and onwards, many famous rabbis (and often their followers) immigrated to the Land of Israel. These included Nahmanides

, Yechiel of Paris

with several hundred of his students, Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk

and 300 of his followers, and over 500 disciples (and their families) of the Vilna Gaon

known as Perushim

, among others.

Jews in Catholic states were banned from owning land and from pursuing a variety of professions. From the 13th century Jews were required to wear identifying clothes such as special hats or stars on their clothing

. This form of persecution originated in tenth century Baghdad and was copied by Christian rulers. Constant expulsions and insecurity led Jews to adopt artisan professions that were easily transferable between locations (such as furniture making or tailoring).

Persecution in Spain and Portugal led large number of Jews there to convert to Christianiy, however many continued to secretly practice Jewish

rituals. The Church responded by creating the Inquisition

in 1478 and by expelling all remaining Jews in 1492

. In 1542 the inquisition expanded to include the Papal States

. Inquisitors could arbitrarily torture suspects and many victims were burnt alive.

In 1516 the state of Venice decreed that Jews would only be allowed to reside in a walled area adjacent to Venice

called the Ghetto

. Ghetto residents had to pay a daily poll tax

and could only stay a limited amount of time. In 1555 the Pope decreed that Jews in Rome were to face similar restrictions. The requirement for Jews to live in Ghettos spread across Europe and Ghettos were frequently highly overcrowded and heavily taxed. They also provided a convenient target for mobs (pogrom

).

Jews were expelled from England

in 1290. A ban remained in force that was only lifted when Oliver Cromwell

overthrew

the Catholic monarchy in 1649 (see Resettlement of the Jews in England

).

Persecution of Jews began to decline following Napoleon

's conquest of Europe after the French Revolution

although the short lived Nazi Empire resurrected most practices.

In 1965 the Catholic Church formally ended

the doctrine of holding Jews collectively responsible for the death of Jesus.

in Europe led to an 18th and 19th century Jewish enlightenment movement in Europe, called the Haskalah

. In 1791, the French Revolution

led France to become the first country in Europe to grant Jews legal equality. Britain gave Jews equal rights in 1856, Germany in 1871. The spread of western liberal ideas among newly emancipated Jews created for the first time a class of secular Jews who absorbed the prevailing ideas of enlightenment, including rationalism

, romanticism

, and nationalism

.

However, the formation of modern nations in Europe accompanied changes in the prejudices against Jews. What had previously been religious persecution now became a new phenomenon, Racial antisemitism and acquired a new name: antisemitism. Antisemites saw Jews as an alien religious, national and racial group and actively tried to prevent Jews from acquiring equal rights and citizenship. The Catholic press was at the forefront of these efforts and was quietly encouraged by the Vatican which saw its own decline in status as linked to the equality granted to Jews. By the late 19th century, the more extreme nationalist movements in Europe often promoted physical violence against Jews who they regarded as interlopers and exploiters threatening the well-being of their nations.

s and persecution in Tzarist Russia. From 1791 they were only allowed to live in the Pale of Settlement

. In response to the Jewish drive for integration and modern education (Haskalah

) and the movement for emancipation, the Tzars imposed tight quotas

on schools, universities and cities to prevent entry by Jews.

From 1827 to 1917 Russian Jewish boys were required to serve 25 years in the Russian army, starting at the age of 12. The intention was to forcibly destroy their ethnic identity, however the move severely radicalized Russia's Jews and familiarized them with nationalism and socialism.

The tsar's chief adviser Konstantin Pobedonostsev

, was reported as saying that one-third of Russia's Jews was expected to emigrate, one-third to accept baptism, and one-third to starve.

Famous incidents includes the 1913 Menahem Mendel Beilis

trial (Blood libel against Jews) and the 1903 Kishinev pogrom

.

Between 1880 and 1928, two million Jews left Russia; most emigrated to the United States

, a minority chose Palestine.

, (Russian) Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk

, (Bosnian) Rabbi Judah Alkalai

and (German) Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer

. Other advocates of Jewish independence include (American) Mordecai Manuel Noah

, (Russian) Leon Pinsker and (German) Moses Hess

.

In 1862 Moses Hess

In 1862 Moses Hess

, an associate of Karl Marx, wrote Rome and Jerusalem. The Last National Question calling for the Jews to create a socialist state in Palestine

as a means of settling the Jewish question

. Also in 1862, German Orthodox Rabbi Kalischer published his tractate Derishat Zion, arguing that the salvation of the Jews, promised by the Prophets, can come about only by self-help. In 1882, after the Odessa pogrom

, Judah Leib Pinsker published the pamphlet Auto-Emancipation

, arguing that Jews could only be truly free (automatically emancipated) in their own country and analyzing the persistent tendency of Europeans to regard Jews as aliens:

Pinsker established the Hibbat Zion

movement to actively promote Jewish settlement in Palestine. In 1890, the "Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Eretz Israel" (better known as the Odessa Committee

) was officially registered as a charitable organization

in the Russian Empire

, and by 1897, it counted over 4,000 members.

public discourse in the early 19th century, at about the same time as the British Protestant Revival.

Not all such attitudes were favorable towards the Jews; they were shaped in part by a variety of Protestant beliefs,

or by a streak of philo-Semitism

among the classically educated British elite, or by hopes to extend the Empire. (See The Great Game

)

At the urging of Lord Shaftesbury, Britain established a consulate in Jerusalem in 1838, the first diplomatic appointment in the city. In 1839, the Church of Scotland

sent Andrew Bonar

and Robert Murray M'Cheyne

to report on the condition of the Jews there. The report was widely published and was followed by a "Memorandum to Protestant Monarchs of Europe for the restoration of the Jews to Palestine." In August 1840, The Times reported that the British government was considering Jewish restoration. Correspondence in 1841-42 between Moses Montefiore

, the President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews

and Charles Henry Churchill

, the British consul in Damascus, is seen as the first recorded plan proposed for political Zionism.

Lord Lindsay wrote in 1847: "The soil of Palestine still enjoys her sabbaths, and only waits for the return of her banished children, and the application of industry, commensurate with her agricultural capabilities, to burst once more into universal luxuriance, and be all that she ever was in the days of Solomon."

In 1851, correspondence between Lord Stanley

, whose father became British Prime Minister the following year, and Benjamin Disraeli, who became Chancellor of the Exchequer

alongside him, records Disraeli's proto-Zionist views: "He then unfolded a plan of restoring the nation to Palestine

- said the country was admirably suited for them - the financiers all over Europe might help - the Porte

is weak - the Turks/holders of property could be bought out - this, he said, was the object of his life...."Coningsby

was merely a feeler - my views were not fully developed at that time - since then all I have written has been for one purpose. The man who should restore the Hebrew race to their country would be the Messiah - the real saviour of prophecy!" He did not add formally that he aspired to play this part, but it was evidently implied. He thought very highly of the capabilities of the country, and hinted that his chief object in acquiring power here would be to promote the return". 26 years later, Disraeli wrote in his article entitled "The Jewish Question is the Oriental Quest" (1877) that within fifty years, a nation of one million Jews would reside in Palestine under the guidance of the British.

Moses Montefiore

visited the Land of Israel seven times and fostered its development.

In 1842, Mormon leader Joseph Smith, Jr. sent a representative, Orson Hyde

, to dedicate the land of Israel for the return of the Jews. Protestant theologian William Eugene Blackstone

submitted a petition to the US president in 1891; the Blackstone Memorial

called for the return of Palestine to the Jews.

and the Rothschild

s responded to the persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe by sponsoring agricultural settlements for Russian Jews in Palestine. The Jews who migrated in this period are known as the First Aliyah

. Aliyah is a Hebrew word meaning "ascent," referring to the act of spiritually "ascending" to the Holy Land and a basic tenet of Zionism.

The movement of Jews to Palestine was opposed by the Haredi communities who lived in the Four Holy Cities

, since they were very poor and lived off charitable donations from Europe, which they feared would be used by the newcomers. However from 1800 there was a movement of Sephardi businessmen from North Africa and the Balkans to Jaffa and the growing community there perceived modernity and Aliyah as the key to salvation. Unlike the Haredi communities, the Jaffa community did not maintain separate Ashkenazi and Sephardi institutions and functioned as a single unified community.

Founded in 1878, Rosh Pinna

and Petah Tikva

were the first modern Jewish settlements.

In 1881-1882 the Tzar sponsored a huge wave of progroms in the Russian Empire

and a massive wave of Jews began leaving, mainly for America. So many Russian Jews arrived in Jaffa that the town ran out of accommodation and the local Jews began forming communities outside the Jaffa city walls. However the migrants faced difficulty finding work (the new settlements mainly needed farmers and builders) and 70% ultimately left, mostly moving on to America. One of the migrants in this period, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda

set about modernizing Hebrew so that it could be used as a national language.

Rishon LeZion was founded on 31 July 1882 by a group of ten members of Hovevei Zion

from Kharkov (today's Ukraine

). In 1887 Neve Tzedek

was built just outside Jaffa. Over 50 Jewish settlements were established in this period.

In 1890, Palestine, which was part of the Ottoman Empire

, was inhabited by about half a million people, mostly Muslim

and Christian Arabs, but also some dozens of thousands Jews.

, 19 years old, founded Kadimah, the first Jewish student association in Vienna and printed Pinsker's pamphlet Auto-Emancipation

.

The Dreyfus Affair

, which erupted in France

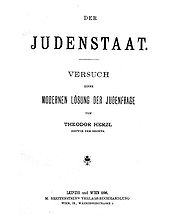

in 1894, profoundly shocked emancipated Jews. The depth of antisemitism in the first country to grant Jews equal rights led many to question their future prospects among Christians. Among those who witnessed the Affair was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist, Theodor Herzl

. Herzl was born in Budapest

and lived in Vienna (Jews were only allowed to live in Vienna from 1848), who published his pamphlet Der Judenstaat

("The Jewish State") in 1896 and Altneuland

("The Old New Land") in 1897. He described the Affair as a personal turning point, Herzl argued that the creation of a Jewish state would enable the Jews to join the family of nations and escape antisemitism.

Herzl

infused political Zionism with a new and practical urgency. He brought the World Zionist Organization

into being and, together with Nathan Birnbaum, planned its First Congress at Basel

in 1897.

, the following agreement, commonly known as the Basel Program, was reached:

"Under public law" is generally understood to mean seeking legal permission from the Ottoman rulers for Jewish migration. In this text the word "home" was substituted for "state" and "public law" for "international law" so as not to alarm the Ottoman Sultan.

(WZO) met every year, then, up to the Second World War, they gathered every second year. Since the creation of Israel, the Congress has met every four years.

Congress delegates were elected by the membership. Members were required to pay dues known as a "shekel," At the congress, delegates elected a 30-man executive council, which in turn elected the movement's leader. The movement was democratic and women had the right to vote, which was still absent in Great Britain in 1914.

The WZO's initial strategy was to obtain permission from the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II

to allow systematic Jewish settlement in Palestine. The support of the German Emperor, Wilhelm II, was sought, but unsuccessfully. Instead, the WZO pursued a strategy of building a homeland through persistent small-scale immigration and the founding of such bodies as the Jewish National Fund

(1901 - a charity which bought land for Jewish settlement) and the Anglo-Palestine Bank (1903 - provided loans for Jewish businesses and farmers).

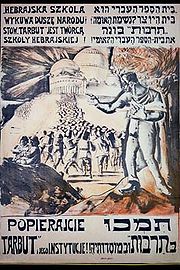

While Herzl believed that the Jews needed to return to their historic homeland as a refuge from antisemitism, the opposition, led by Ahad Ha'am, believed that the Jews must revive and foster a Jewish national culture and, in particular strove to revive the Hebrew language. Many also adopted Hebraized surnames.

The opposition became known as Cultural Zionists.

Important Cultural Zionists include Ahad Ha'am, Chaim Weizmann

, Nahum Sokolow

and Menachem Ussishkin.

, suggested the British Uganda Programme, land for a Jewish state in "Uganda

" (in today's Uasin Gishu District

, Eldoret

, Kenya

). Herzl initially rejected the idea, preferring Palestine, but after the April 1903 Kishinev pogrom

, Herzl introduced a controversial proposal to the Sixth Zionist Congress to investigate the offer as a temporary measure for Russian Jews in danger. Despite its emergency and temporary nature, the proposal proved very divisive, and widespread opposition to the plan was fueled by a walkout led by the Russian Jewish delegation to the Congress. Nevertheless, a committee was established to investigate the possibility, which was eventually dismissed in the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905. After that, Palestine became the sole focus of Zionist aspirations.

Israel Zangwill

left the main Zionist movement over this decision and founded the Jewish Territorialist Organization

(ITO). The territorialists

were willing to establish a Jewish homeland anywhere, but failed to attract significant support and were dissolved in 1925.

In 1903, following the Kishinev Pogrom

, a variety of Russian antisemities, including the Black Hundreds and the Tsarist Secret Police, began combining earlier works alleging a Jewish plot to take control of the world into new formats. One particular version of these allegations, "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

" (subtitle "Protocols extracted from the secret archives of the central chancery of Zion"), arranged by Sergei Nilus

, achieved global notability. In 1903, the editor claimed that the protocols revealed the menace of Zionism:

The book contains fictional minutes of an imaginary

meeting in which alleged Jewish leaders plotted to take over the world. Nilus later claimed they were presented to the elders by Herzl (the "Prince of Exile") at the first Zionist congress. A Polish edition claimed they were taken from Herzl's flat in Austria and a 1920 German version renamed them "The Zionist Protocols".

, who led the movement until 1911. During this period, the movement was based in Berlin (Germany's Jews were the most assimilated

) and made little progress, failing to win support among the Young Turks

after the collapse of the Ottoman Regime. From 1911 to 1921, the movement was led by Dr. Otto Warburg

.

. However, as the cultural and socialist Zionists increasingly broke with tradition and used language contrary to the outlook of most religious Jewish communities, many orthodox religious organizations began opposing Zionism. Their opposition was based on its secularism and on the grounds that only the Messiah

could re-establish Jewish rule in Israel. Therefore, most Orthodox Jews maintained the traditional Jewish belief that while the Land of Israel was given to the ancient Israelites by God

, and the right of the Jews to that land was permanent and inalienable, the Messiah must appear before the land could return to Jewish control.

While Zionism aroused Ashkenazi

orthodox antagonism in Europe (probably due to Modernist European antagonism to organized religion), and also in the United States, it aroused no such antagonism in the Islamic world.

Prior to the Holocaust

, Reform Judaism

rejected Zionism as inconsistent with the requirements of Jewish citizenship in the diaspora.

, Leon Trotsky

provided arms so the Zionists could protect the Jewish community and this prevented a pogrom. Zionist leader Jabotinsky eventually led the Jewish resistance in Odessa. During his subsequent trial Trotsky produced evidence that the Police had organized the effort to create a pogrom in Odessa.

The vicious pogroms led to a wave of immigrants to Palestine. This new wave expanded the Revival of the Hebrew language. In 1909 a group of 65 Zionists laid the foundations for a modern city in Palestine. The city was named after the Hebrew title of Herzl's book "The Old New Land

" - Tel-Aviv. Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv

had a modern "scientific" school, the Herzliya Hebrew High School

, the first such school to teach only in Hebrew. All the cities affairs were conducted in Hebrew.

In Jerusalem, foundations were laid for a Jewish University (the Hebrew University), one which would teach only in Hebrew and which the Zionists hoped would help them prove their usefulness to the Turks (this did not come to fruition until 1918). In Haifa, the cornerstone was laid for a Jewish Technical school, the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology.

Jewish migrants and organizations began making large land purchases, in particular buying malarial swamps (of which there were many) and draining them to produce highly fertile land.

In 1911 a socialist commune was given some land near the Sea of Galilee, forming the first Kibbutz

, Degania.

, Karl Marx

wrote "Money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist." Concluding with the words: "the emancipation of the Jews is the emancipation of mankind from Judaism". Marx specifically stated that there would be no Jews in a socialist paradise and Marxist Jews were often highly anxious to reject their association with orthodox Jews and make a new start.

In Eastern Europe the General Jewish Labour Bund called for Jewish autonomy

within Eastern Europe and promoted Yiddish as the Jewish language. Like Zionism, the Bund was founded in 1897. It also claimed national rights for Jews, but within Eastern Europe. The Bund was part of the socialist movement and claimed Jewish national rights within the socialist movement, which recognized various national groups but not Jews. The socialist movement had failed to publicly condemn the pogroms. The Bund leadership opposed Zionism and Orthodox Judaism. Socialist Zionism competed with the Bund (and other socialist parties) for the hearts and minds of Jewish socialists.

In 1917 there was a Russian revolution and the Bolsheviks took power. At this point the Bund had 30,000 members in Russia, compared to 300,000 Zionist members (about 10% of these were Marxists). Antisemites assumed the Bolsheviks were largely Jewish (calling it Jewish Bolshevism

) and the Bolsheviks did give Jews equal rights as individuals, however they were intolerant of religious Judaism and of Zionism, both of which were eventually banned.

The Bund disbanded and most members joined the Yevsektsia, a Jewish section of the Bolshevik organization created by Stalin who was People's Commissariat of Nationalities.The Yevsektsia worked to end Jewish communal and religious life:

The 1918 - 1923 Russian civil war

followed the revolution and saw terrible atrocities against Jews, particularly in the Ukraine:

During the Civil War, the Marxist Zionist movement, Poale Zion

led by Ber Borochov

, requested to form Jewish Brigades within the Red Army. Trotsky supported the request but opposition from the Yevsektsia led to the proposal's failure. Poale Zion continued to exist in the USSR until 1928. The future Israeli Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion was a member of the Israeli branch of the movement.

In 1924 Stalin became the ruler of the USSR and in 1928 Trotsky was sent into exile. In 1928 a Jewish Autonomous Oblast

was created in the Russian Far East

and Hebrew was outlawed (the only language to be outlawed in the USSR). Few Jews were tempted by the Soviet Jewish Republic and as of 2002 Jews constitute only about 1.2% of its population.

mentality" among the Jewish people and established rural communes in Israel called "Kibbutz

im". Major theoreticians of Socialist Zionism included Moses Hess

, Nachman Syrkin

, Ber Borochov

and A. D. Gordon

, and leading figures in the movement included David Ben-Gurion

and Berl Katznelson

. Socialist Zionists rejected Yiddish as a language of exile, embracing Hebrew as the common Jewish tongue.

Gordon believed that the Jews lacked a "normal" class structure and that the various classes that constitute a nation had to be created artificially. Socialist Zionists therefore set about becoming Jewish peasants and proletarians and focused on settling land and working on it. According to Gordon "the land if Israel is bought with labour: not with blood and not with fire".

Socialist Zionism became a dominant force in Israel. However, it exacerbated the schism between Zionism and Orthodox Judaism

.

Socialist Zionists formed youth movements which became influential organizations in their own right including Habonim Dror

, Hashomer Hatzair

, Machanot Halolim and HaNoar HaOved VeHaLomed

. During British rule the lack of available immigration permits to Palestine, led the youth movements to operate training programs in Europe which prepared Jews for migration to Palestine. As a result most Socialist-Zionist immigrants arrived already speaking Hebrew, trained in agriculture and prepared for life in Palestine.

In 1911, Zionist activist Hannah Meisel Shochat established Havat Ha'Almot (the girl's farm) to train Zionist women in farming so as to assist in the Zionist program of developing the land for mass settlement. The famous poet Rachel Bluwstein

was one of the graduates. Zionist settlers were usually young and far from their families so a relatively permissive culture was able to develop. Within the Kibbutz movement child rearing was done communally thus freeing women to work (and fight) alongside the men.

Roza Pomerantz-Meltzer

was the first woman elected to the Sejm

, the Parliament of Poland

. She was elected in 1919 as a member of a Zionist party.

In Mandatory Palestine women in Jewish towns could vote in elections before women won the right to vote in Britain.

noted the movement's spread: "not only in the number of Jews affiliated with the Zionist organization and congress, but also in the fact that there is hardly a nook or corner of the Jewish world in which Zionistic societies are not to be found."

Support for Zionism was not a purely European and Ashkenazi phenomenon. In the Arab world, the first Zionist branches opened in Morocco

only a few years after the Basel conference, and the movement became popular among Jews living within the Arab and Muslim world. Although levels of persecution were generally lower there, Jewish residents still faced some religious persecution, prejudice and occasional violence. A number of the founders of the city of Tel Aviv

were Moroccan Jewish immigrants. Ottoman Salonika had a vigorous Zionist movement by 1908.

While Zionist leaders and advocates followed conditions in the land of Israel and travelled there regularly, their concern before 1917 was with the future of the small Jewish settlement. A Jewish state seemed highly unlikely at this point and realistic aspirations focussed on creating a new centre for Jewish life. The future of the land's Arab inhabitants concerned them as little as the welfare of the Jews concerned Arab leaders.

became involved in Zionism, just before the First World War, that Zionism gained significant support. By 1917, the American Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist Affairs, which Brandeis chaired had increased American Zionist membership ten times to 200,000 members, and “thenceforth became the financial center for the world Zionist movement”.

As in the US, England had experienced a rapid growth in their Jewish minority. About 150,000 Jews migrated there from Russia in the period 1881–1914. With this immigration influx, pressure grew from British voters to halt it; added to the established knowledge in British society of Old Testament

scripture, Zionism became an attractive solution for both Britain and the Empire.

In the search for support, Herzl, before his death, had made the most progress with the German Kaiser, joining him on his 1898 trip to Palestine. At the outbreak of war in 1914, the offices of the Zionist Organization were located in Berlin and led by Otto Warburg

, a German citizen. With different national sections of the movement supporting different sides in the war, Zionist policy was to maintain strict neutrality and "to demonstrate complete loyalty to Turkey," the German ally controlling Palestine.

Following Turkey's entry into World War I

in August however, the Zionists were expelled from Tel Aviv and its environs. When the war started in 1914, most Jews viewed Tsarist Russia

, on the Allied side, as the historic enemy of the Jewish people and there was tremendous support for Germany. In much of Eastern Europe the advancing Germans were regarded as liberators by the Jews. Russian Jewish immigrants to Britain avoided the draft. In England the Polish Zionist, Ze'ev Jabotinsky, worked to create a Jewish division in the British army. For the British, the Jewish Legion

, was a means of recruiting Russian immigrants to the British war effort. The legion was dominated by Zionist volunteers.

In the United States, still officially neutral, most Russian and German Jews supported the Germans as did much of the large Irish American

community. Britain was anxious to win US support for its war effort, and winning over Jewish financial and popular support in the US was considered vital.

The most prominent Russian-Zionist migrant in Britain was chemist Chaim Weizmann

. Weizmann developed a new process to produce Acetone

, a critical ingredient in manufacturing explosives that Britain was unable to manufacture in sufficient quantity. In 1915, the British government fell as a result of its inability to manufacture enough artillery shells

for the war effort. In the new Government, David Lloyd George

became the minister responsible for armaments, and asked Weizmann to develop his process for mass production.

Lloyd George was an evangelical Christian and pro-Zionist. According to Lloyd George when he asked Weizmann about payment for his efforts to help Britain, Weizmann told him that he wanted no money, just the rights over Palestine. Weizmann became a close associate of Lloyd George (Prime Minister from 1916) and the First Lord of the Admiralty (Foreign Secretary from 1916), Arthur Balfour

.

In 1916 Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca

(in Arabia), began an "Arab Revolt

" hoping to create an Arab state in the Middle East. In the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence British representatives promised they would allow him to create such a state. They also provided him with large sums of money to fund his revolt.

In February 1917 the Tsar was overthrown

and Alexander Kerensky

became Prime Minister of the Russian Empire. Jews were prominent in the new government and the British hoped that Jewish support would help keep Russia in the war. In June 1917 the British army, led by Edmund Allenby, invaded Palestine. The Jewish Legion

participated in the invasion and Jabotinsky was awarded for bravery. Arab forces conquered Transjordan

and later took over Damascus.

In August 1917, as the British cabinet discussed the Balfour Declaration, Edwin Samuel Montagu

, the only Jew in the British Cabinet and a staunch anti-Zionist, "was passionately opposed to the declaration on the grounds that (a) it was a capitulation to anti-Semitic bigotry, with its suggestion that Palestine was the natural destination of the Jews, and that (b) it would be a grave cause of alarm to the Muslim world.". Additional references to the future rights of non-Jews in Palestine and the status of Jews worldwide, were thus inserted by the British cabinet, reflecting the opinion of the only Jew within it. As the draft was finalized, the term "state" was replaced with "home", and comments were sought from Zionists abroad. Louis Brandeis, a member of the US Supreme Court, influenced the style of the text and changed the words "Jewish race" to "Jewish people".

On November 2, the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour

, made his landmark Balfour Declaration of 1917, expressing the government's view in favour of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people", and specifically noting that its establishment must not "prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

As the declaration was being finalized, the Bolsheviks took over

Russia. On 23 November, they released a copy of the previously secret Sykes–Picot Agreement, among others, publishing its full text in Izvestia

and Pravda

, and it was subsequently printed in the Manchester Guardian on November 26. This caused Britain great embarrassment, because of the conflicting plans and promises it revealed.

(who had also spent the first world war in Britain). Weizmann resumed presidency of the WZO in 1935 and led it until 1946.

After the defeat and dismantling of the Ottoman Empire by European colonial powers in 1918, the League of Nations

After the defeat and dismantling of the Ottoman Empire by European colonial powers in 1918, the League of Nations

endorsed the full text of the Balfour Declaration and established the British Mandate

for Palestine (Full text:).

In addition to accepting the Balfour Declaration policy statement, the League included that “[a]n appropriate Jewish agency

shall be recognised as a public body for the purpose of advising and co-operating with the Administration of Palestine..." This inclusion paralleled a similar proposal made by the Zionist Organization

during the Paris Peace Conference

.

The Zionist movement entered a new phase of activity. Its priorities were encouraging Jewish settlement in Palestine, building the institutional foundations of a Jewish state and raising funds for these purposes. The 1920s did see a steady growth in the Jewish population and the construction of state-like Jewish institutions, but also saw the emergence of Palestinian Arab nationalism and growing resistance to Jewish immigration.

(the first Chief Rabbi of Palestine) and his son Zevi Judah, began to develop the concept of Religious Zionism

. At the time, Kook was concerned that growing secularism of Zionist supporters and increasing antagonism towards the movement from the largely non-Zionist Orthodox community might lead to a schism between them. He therefore sought to create a brand of Zionism which would serve as a bridge between Jewish Orthodoxy and secular Jewish Zionists, for the benefit of the overall Zionist endeavor.

The Religious Zionists established a youth movement called Bnei Akiva

in 1929, and a number of Religious Kibbutzim

.

, the British banned Jabotinsky from re-entering Palestine, and until his death in 1940, he advocated the more militant revisionist ideology in Europe and America. In 1935, he and the Revisionists left the mainstream Zionist Organization

and formed the New Zionist Organization. Following mainstream Zionism's' acceptance of their earlier militant demand for a Jewish state they eventually rejoined in 1946.

During this period, Revisionist Zionism was detested by the competing Socialist Zionist movement, which saw them as being capitalist and influenced by Fascism

; the movement also caused a great deal of concern among Arab Palestinians.

Revisionism was popular in Poland but lacked large support in Palestine. The Revisionists refused to comply with British quotas on Jewish migration, and, following the election of Hitler in Germany, the Revisionist youth movements HeHalutz

and Beitar began to organize illegal Jewish migration to Palestine. In Europe and America they advocated pressing Britain to allow mass Jewish emigration and the formation of a Jewish Army in Palestine. The army would force the Arab population to accept mass Jewish migration and promote British interests in the region.

" program. The latter was an effort to increase Jewish immigrant employment, secure the creation of a Jewish proletariat, and to prevent Zionist settlement from turning into a standard colonial enterprise. Initially, it sought to develop separate settlements and economies and campaigned for the exclusive employment of Jews; it later campaigned against the employment of Arabs. Its adverse effects on the Arab majority were increasingly noted by the mandatory administration.

In 1919 Hashemite

Emir Faisal

, signed the Faisal–Weizmann Agreement. He wrote:

In their first meeting in June 1918 Weizmann had assured Faisal that

Initially Palestinian Arabs looked to the Arab-nationalist leaders to create a single Arab state, however Faisal's agreement with Weizmann led Palestinian-Arabs to develop their own brand of nationalism and call for Palestine to become a state governed by the Arab majority, in particular they demanded an elected assembly.

Zionist supporters were by now aware of Arab opposition, and this led the movement in 1921 to pass a motion calling on the leadership to "forge a true understanding with the Arab nation".

In 1921, Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

In 1921, Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

was appointed as Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

by the Palestine High Commissioner Herbert Samuel

, after he had been pardoned for his role in the 1920 Palestine riots

. During the following decades, he became the focus of Palestinian opposition to Zionism.

The Mufti believed that Jews were seeking to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem

on the site of the Dome of the Rock

and Al-Aqsa Mosque

. This led to a long confrontation over the use of the Kotel

, also known as the Wailing Wall, which was owned by the Moslem authorities

but was sacred to Jews.

Religious tension, an international economic crisis (affecting crop prices) and nationalist tension (over Zionist immigration) led to the 1929 Palestine riots

. In these religious-nationalist riots Jews were massacred in Hebron

and the survivors forced to leave the town. Devastation also took place in Safed

and Jerusalem.

In 1936 an Arab uprising occurred, which lasted for three years. The Supreme Muslim Council

in Palestine, led by the Mufti, organized the revolt. During the revolt the Mufti was forced to flee to Iraq, where he was involved in a pro-Nazi coup during which the Jewish areas of Baghdad were subjected to a pogrom

.

In 1939 he rejected as insufficient the British White Paper

which imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration and land acquisition by Jews.

After the British reoccupied Iraq the Mufti joined the Nazis. He worked with Himmler

and aided the SS

his main role was broadcasting propaganda and recruiting Moslems, primarily for the Waffen SS in Bosnia

. There is also evidence that he was implicated in the Nazi extermination program.

In 1948 the Mufti returned to Egypt. He was involved in the short-lived All-Palestine Government

sponsored by Egypt but was sidelined by most of the Arab countries.

expressed his concern in a letter to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt

lest the US support for Zionism will infringe on the rights of the Arabs of Palestine. On April 5, 1945, the President replied in a letter to the King that

Following Roosevelt's death, the Truman administration publicly adhered to the policy announced in the letter in an official statement released on October 18, 1945.

Churchill also restricted Jewish migration to an annual quota decided by the British. Certificates allowing migration were distributed by the Jewish Agency. Jews with 1000 Pounds in cash or Jewish professionals with 500 Pounds in cash could emigrate freely. Churchill's reforms made it hard for Arab Jews

, Orthodox Jews and Revisionist Zionists from Poland to migrate to Palestine as the Jewish Agency was dominated by European Zionists, and increasingly by Socialist Zionists.

Immigration restrictions did, however mean that Jewish immigrants to Palestine had to prove their loyalty and dedication by spending years preparing for migration. Many immigrants arrived after rigorous preparation including agricultural and ideological training and learning Hebrew.

The rise to power of Adolf Hitler

in Germany in 1933 produced a powerful new impetus for increased Zionist support and immigration to Palestine. The long-held assimilationist and non-Zionist view that Jews could live securely as minorities in European societies was deeply undermined, since Germany had been regarded previously as the country in which Jews had been most successfully integrated. With nearly all other countries closed to Jewish immigration, a new wave of migrants headed for Palestine. Those unable to pay the fees required for immediate entry by the British had to join the waiting lists.

Nazi efforts to induce Jews to leave Germany were made, but were undermined by their refusal to allow them to take their property also. In response, Haim Arlozorov of the Jewish Agency negotiated the Haavara Agreement

with the Nazis, whereby German Jews could buy and then export German manufactured goods to Palestine. In Palestine the goods were later sold and the income returned to the migrants. As a result of this agreement, the influx of capital gave a much-needed economic boost in the midst of the great depression

. Arlozorov, however, was assassinated shortly after his return, it was generally believed by members of the Irgun

(in recent years it has been suggested that Nazi propaganda Minister Goebbels

may have ordered the assassination to hide Arlozorov's connection with his wife

).

Starting in 1934, the Revisionists also began organizing illegal immigration, and combined, the Jewish population of Palestine rose rapidly. While these conditions also led to increased Arab immigration, the rapid rise in Jewish immigrants eventually led to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine.

By 1938, the increasing pressure put on European Jews also led mainstream Zionists to organize illegal immigration.

, established a new party, the British Union of Fascists

, which claimed that "the Jews" were leading Britain to war and campaigned for peace with Germany. British support for Zionism was further undermined by the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine and concern that millions of Jews would soon be seeking entry to Palestine. The Nuremberg Laws

effectively revoked the citizenship of the 500,000 Jews of Germany, making them refugees in their own country. In March 1938 Hitler annexed Austria

making its 200,000 Jews stateless refugees. In September the British agreed to Nazi annexation

of the Sudetenland

making a further 100,000 Jews refugees.

In the absence of alternative destinations

, over 100,000 German Jews headed for Palestine.

In 1939 the British issued a White Paper

, in which they declared that a Jewish National Home now existed and that their obligations under the mandate were fulfilled. Further migration would be harmful to the Arab population.

A further 10,000 Jews a year were to be admitted from 1939 to 1944 as well as a one-time allowance of 25,000 in view of the situation in Europe. After that Jewish migration would require (the extremely unlikely) agreement of the Arab majority (by this time Jews were about a third of the population). The British promised Palestinians independence by 1949 and imposed restrictions on land purchases by Jews.

The British were concerned about maintaining Arab support as Italian Fascist and German Nazi propaganda was targeting the Arab world (and winning support). Jewish support in the fight against Fascism was guaranteed. In Palestine, Zionists increasingly viewed the British as an enemy, but they deemed the fight against the Nazis more important. In 1940 a group led by Avraham Stern

, later known as Lehi

, left the Irgun

over its refusal to fight the British.

. Zionism and Orthodox Judaism were banned and Jews were prominent among the victims of the Soviet genocide. These figures suggest Zionism was very popular among Jews.

The following figures relate to the last pre-war Zionist congress in Geneva, 1939. Elections for the congress were held in 48 countries and 529 delegates attended. Members of the movement voted for the parties. Each party submitted a delegate list. Seats were distributed to the parties according to the number of votes they obtained and candidates elected in the order in which they were named on the list. This system today forms the basis for Israeli elections.

, a group of 1213 Jews who survived the whole war while making trouble for the Nazis. Nazi allies Hungary

, Romania

, Slovakia

and Croatia

(mainly Romania) were responsible for the deaths of at least 10% of the 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust. Axis governments, local police forces and local volunteers across Europe played a critical role in rounding up or executing Jews for the Nazis.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

of January and April 1943 included the participation of both right- and left-leaning Zionist organizations. Zionists of all political spectra played a leading role in the struggle. The uprising's left-leaning survivors eventually made their way to Palestine and founded two Kibbutzim, Lohamei HaGeta'ot and Yad Mordechai

.

In Palestine the Zionist leadership instructed all able-bodied Jews to volunteer for the British Army. In addition there was an effort to parachute fighters into Europe, though little came of this. Fearing a Nazi invasion, the Jewish community prepared for a final stand to be made against the Nazis.

Overall the yishuv leaders had not done enough in publicizing and trying to stop the Holocaust. While they could have succeeded in saving thousands of Jews if rescuing Jews had been their top priority, rather than state creation, they had no power to "stop" the Holocaust. In the words of Tom Segev

:

Efforts were made to offer the Nazis money for the release of Jews. However, these efforts were systematically (and, according to Segev, cynically) destroyed by the British.

The 1942 Zionist conference could not be held because of the war. Instead 600 Jewish leaders (not just Zionists) met at the Biltmore Hotel in New York and adopted a statement known as the Biltmore Program. They agreed that the Zionist movement would seek the creation of a Jewish state after the war and that all Jewish organizations would fight to ensure free Jewish migration into Palestine.

This calamity led to important changes in Jewish and Zionist politics:

, to investigate the situation of the Jewish survivors ("Sh'erit ha-Pletah

") in Europe. Harrison reported that

Despite winning the 1945 British election with a manifesto promising to create a Jewish state in Palestine, the Labour Government succumbed to Foreign Office pressure and kept Palestine closed to Jewish migration.

In Europe former Jewish partisans

led by Abba Kovner

began to organize escape routes ("Berihah

") taking Jews from Eastern Europe down to the Mediterranean where the Jewish Agency organized ships ("Aliyah Bet") to illegally carry them to Palestine.

The British government responded by trying to force Jews to return to their places of origin. Holocaust survivors entering the British Zone were denied assistance or forced to live in hostels with former Nazi collaborators (Britain gave asylum to a large number of Belorussian Nazi collaborators

after the war). In American-controlled zones, political pressure from Washington allowed Jews to live in their own quarters and meant the US Army helped Jews trying to escape the centres of genocide.

Despite the death of almost a third of the world's Jews during the Second World War, the number of fee paying members of the Zionist movement continued to grow. The December 1946 Zionist congress in Basle (Switzerland) attracted 375 delegates from 43 countries representing two million fee paying members. As before the largest parties were the Socialist Zionist parties although these lacked a full majority. Only ten of the delegates were British Jews.

investigated the situation and offered two solutions :

From the Zionist point of view, the second option corresponded to their goal and they gave full support to this.

On 29 November the United Nations General Assembly

voted to partition Palestine into an Arab state and a Jewish state (with Jerusalem becoming an international enclave). Amid public rejoicing in Jewish communities in Palestine, the Jewish Agency accepted the plan. The Palestinian Arab leadership and the Arab League rejected the decision and announced that they would not abide by it. Civil conflict between the Arabs and Jews in Palestine

ensued immediately.

.

David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel objected to the Zionist Organization's more moderate approach in attaining Jewish statehood, and later objected to its continued existence, which he saw as competition and largely irrelevant following the formation of the state; he clashed with the leadership of the international Zionist Organization. The ZO's main activities at this point were relegated to assisting persecuted Jews, usually in countries where Zionism was illegal, and assisting immigration to Israel in countries where Jews faced little persecution, plus raising awareness and encouraging support for Israel.

Most Diaspora Jews identify with Zionism and have done so since the 1930s, in the sense that they support the State of Israel, even if they do not choose to emigrate; the Zionist movement also has undertaken a variety of roles to encourage support for Israel. These have included encouraging immigration and assisting immigrants in absorption and integration, fund-raising on behalf of needs and development, encouraging private capital investment, and mobilizing public opinion support for Israel internationally. Worldwide Jewish political and financial support has been of vital importance for Israel.

The 1967 war between Israel and the Arab states (the "Six-Day War

") marked a major turning point in the history of both Israel and of Zionism. Israeli forces captured the eastern half of Jerusalem, including the holiest of Jewish religious sites, the Western Wall

of the ancient Temple. They also took over the remaining territories of pre-1948 Palestine, the West Bank

(from Jordan) the Gaza Strip

(from Egypt

) as well as the Golan Heights (from Syria).

The 28th Zionist Congress (Jerusalem, 1968) adopted the following five principles, known as the "Jerusalem Program", as the aims of contemporary Zionism:

The election of 1977

, characterized as “the revolution”, brought the nationalistic, right-wing, Revisionist Zionist

, Likud

Party to power, after thirty years in opposition to the dominant Labor party and indicated further movement to the political right. Joel Greenburg, writing in The New York Times

twenty years after the election, notes its significance and that of related events; he writes:

Control of the West Bank and Gaza placed Israel in the position of control over a large population of Palestinian Arabs. Over the years this has generated conflict between competing core Zionist ideals of an egalitarian democratic state on the one hand, and territorial loyalty to historic Jewish areas, particularly the old city of Jerusalem, on the other. Zionism and its ideological underpinnings have become less important in Israeli politics, except for on-going national debate over the nature of what is meant by a "Jewish State," and the geographic limits of the State of Israel. These debates however, have largely taken place outside Zionist organizations, and within Israeli national politics.

In 1975 the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 was passed. It stated that "zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination." Resolution 3379 was rescinded in 1991 by the Resolution 4686.

In 2001, the first ever environmental Zionist organization, the Green Zionist Alliance

, was founded by a group of American and Israeli environmentalists led by Dr. Alon Tal, Rabbi Michael Cohen and Dr. Eilon Schwartz. The Green Zionist Alliance

focuses on the environment of Israel and its region.

Soviet propaganda backfired in 1967 and led to a major spurt of Jews applying to leave for Israel. The Zionist movement mounted a major campaign to pressure the USSR to allow Soviet Jews to migrate to Israel.

Zionist activists in the USSR studied Hebrew (illegal in the USSR), held clandestine religious ceremonies (circumcision was illegal) and monitored Human Rights

abuses on behalf of western organizations. The most prominent activist was Anatoly Sharansky, who was sentenced to 15 years in prison for his actions before being exchanged for a Soviet spy.

Over the years a number of Israeli and American Jewish organizations, most notably SSSJ

and NCSJ

, mounted a political campaign to free Soviet Jews. Aided with the efforts of Reagan administration

, this campaign eventually succeeded in 1987 when most refusniks we released from prison and allowed to immigrate to Israel.

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl , born Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl was an Ashkenazi Jew Austro-Hungarian journalist and the father of modern political Zionism and in effect the State of Israel.-Early life:...

in 1897; however the history of Zionism began earlier and related to Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

and Jewish history

Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, their religion and culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions and cultures. Since Jewish history is over 4000 years long and includes hundreds of different populations, any treatment can only be provided in broad strokes...

. The Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion , also known as Hibbat Zion , refers to organizations that are now considered the forerunners and foundation-builders of modern Zionism....

, or the Lovers of Zion, were responsible for the creation of 20 new Jewish settlements in Palestine between 1870 and 1897.

Before the Holocaust

The Holocaust

The Holocaust , also known as the Shoah , was the genocide of approximately six million European Jews and millions of others during World War II, a programme of systematic state-sponsored murder by Nazi...

the movement's central aims were the creation of a Jewish National Home and cultural centre in Palestine by facilitating Jewish migration

Aliyah

Aliyah is the immigration of Jews to the Land of Israel . It is a basic tenet of Zionist ideology. The opposite action, emigration from Israel, is referred to as yerida . The return to the Holy Land has been a Jewish aspiration since the Babylonian exile...

. After the Holocaust, the movement focussed on creation of a "Jewish state

Jewish state

A homeland for the Jewish people was an idea that rose to the fore in the 19th century in the wake of growing anti-Semitism and Jewish assimilation. Jewish emancipation in Europe paved the way for two ideological solutions to the Jewish Question: cultural assimilation, as envisaged by Moses...

" (usually defined as a secular state with a Jewish majority), attaining its goal in 1948 with the creation of Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

.

Since the creation of Israel, the importance of the Zionist movement as an organization has declined, as the Israeli state has grown stronger.

The Zionist movement continues to exist, working to support Israel, assist persecuted Jews and encourage Jewish emigration to Israel

Aliyah

Aliyah is the immigration of Jews to the Land of Israel . It is a basic tenet of Zionist ideology. The opposite action, emigration from Israel, is referred to as yerida . The return to the Holy Land has been a Jewish aspiration since the Babylonian exile...

. While most Israeli political parties continue to define themselves as Zionist, modern Israeli political thought is no longer formulated within the Zionist movement.

The success of Zionism has meant that the percentage of the world's Jewish population

Jewish population

Jewish population refers to the number of Jews in the world. Precise figures are difficult to calculate because the definition of "Who is a Jew" is a source of controversy.-Total population:...

who live in Israel has steadily grown over the years and today 40% of the world's Jews live in Israel. There is no other example in human history of a "nation

Nation

A nation may refer to a community of people who share a common language, culture, ethnicity, descent, and/or history. In this definition, a nation has no physical borders. However, it can also refer to people who share a common territory and government irrespective of their ethnic make-up...

" being restored after such a long period of existence as a Diaspora

Diaspora

A diaspora is "the movement, migration, or scattering of people away from an established or ancestral homeland" or "people dispersed by whatever cause to more than one location", or "people settled far from their ancestral homelands".The word has come to refer to historical mass-dispersions of...

.

Biblical precedents

The precedence for Jews to return to their ancestral homeland, motivated by strong divine intervention, first appears in the TorahTorah

Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five books of the bible—Genesis , Exodus , Leviticus , Numbers and Deuteronomy Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five...

, and thus later adopted in the Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

. After Jacob

Jacob

Jacob "heel" or "leg-puller"), also later known as Israel , as described in the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, the New Testament and the Qur'an was the third patriarch of the Hebrew people with whom God made a covenant, and ancestor of the tribes of Israel, which were named after his descendants.In the...

and his sons had gone down to Egypt to escape a drought, they were enslaved and became a nation. Later, as commanded by God, Moses

Moses

Moses was, according to the Hebrew Bible and Qur'an, a religious leader, lawgiver and prophet, to whom the authorship of the Torah is traditionally attributed...

went before Pharaoh, demanded, "Let my people go!", and foretold severe consequences

Plagues of Egypt

The Plagues of Egypt , also called the Ten Plagues or the Biblical Plagues, were ten calamities that, according to the biblical Book of Exodus, Israel's God, Yahweh, inflicted upon Egypt to persuade Pharaoh to release the ill-treated Israelites from slavery. Pharaoh capitulated after the tenth...

, if this was not done. Most of the Torah is devoted to the story of the plagues and the Exodus

The Exodus

The Exodus is the story of the departure of the Israelites from ancient Egypt described in the Hebrew Bible.Narrowly defined, the term refers only to the departure from Egypt described in the Book of Exodus; more widely, it takes in the subsequent law-givings and wanderings in the wilderness...

from Egypt, which is estimated at about 1400 BCE. These are celebrated annually during Passover

Passover

Passover is a Jewish holiday and festival. It commemorates the story of the Exodus, in which the ancient Israelites were freed from slavery in Egypt...

, and the Passover meal traditionally ends with the words "Next Year in Jerusalem."

The theme of return to their traditional homeland came up again after the Babylon

Babylon

Babylon was an Akkadian city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which are found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers south of Baghdad...

ians conquered Judea in 641 BCE and the Judeans were exiled to Babylon. In the book of Psalms

Psalms

The Book of Psalms , commonly referred to simply as Psalms, is a book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Bible...

(Psalm 137

Psalm 137

Psalm 137 is one of the best known of the Biblical psalms. Its opening lines, "By the rivers of Babylon..." have been set to music on several occasions....

), Jews lamented their exile while Prophets like Ezekiel

Ezekiel

Ezekiel , "God will strengthen" , is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible. In Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Ezekiel is acknowledged as a Hebrew prophet...

foresaw their return. The Bible recounts how, in 538 BCE Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon and issued a proclamation

Proclamation

A proclamation is an official declaration.-England and Wales:In English law, a proclamation is a formal announcement , made under the great seal, of some matter which the King in Council or Queen in Council desires to make known to his or her subjects: e.g., the declaration of war, or state of...

granting the people of Judah their freedom. 50,000 Judeans, led by Zerubbabel

Zerubbabel

Zerubbabel was a governor of the Persian Province of Judah and the grandson of Jehoiachin, penultimate king of Judah. Zerubbabel led the first group of Jews, numbering 42,360, who returned from the Babylonian Captivity in the first year of Cyrus, King of Persia . The date is generally thought to...

returned. A second group of 5000, led by Ezra

Ezra

Ezra , also called Ezra the Scribe and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra. According to the Hebrew Bible he returned from the Babylonian exile and reintroduced the Torah in Jerusalem...

and Nehemiah

Nehemiah

Nehemiah ]]," Standard Hebrew Nəḥemya, Tiberian Hebrew Nəḥemyāh) is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work rebuilding Jerusalem and purifying the Jewish community. He was the son of Hachaliah, Nehemiah ]]," Standard Hebrew Nəḥemya, Tiberian Hebrew Nəḥemyāh) is the...

, returned to Judea

Judea

Judea or Judæa was the name of the mountainous southern part of the historic Land of Israel from the 8th century BCE to the 2nd century CE, when Roman Judea was renamed Syria Palaestina following the Jewish Bar Kokhba revolt.-Etymology:The...

in 456 BCE.

Precursors

In 1160 David AlroyDavid Alroy

David Alroy was a Jewish pseudo-Messiah born in Amadiya, Iraq. David Alroy studied Torah and Talmud under Hisdai the Exilarch, and Ali, the head of the Academy in Baghdad. He was also well-versed in Muslim literature and known as a worker of magic....

led a Jewish uprising in Kurdistan which aimed to reconquer the promised land. In 1648 Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi, , was a Sephardic Rabbi and kabbalist who claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah. He was the founder of the Jewish Sabbatean movement...

from modern Turkey claimed he would lead the Jews back to Israel. In 1868 Judah ben Shalom

Judah ben Shalom

Judah ben Shalom , also known as Mori Shooker Kohail II or Shukr Kuhayl II , was a Yemenite messianic pretender of the mid-19th century....

led a large movement of Yemenite Jews

Yemenite Jews

Yemenite Jews are those Jews who live, or whose recent ancestors lived, in Yemen . Between June 1949 and September 1950, the overwhelming majority of Yemen's Jewish population was transported to Israel in Operation Magic Carpet...

to Israel. A dispatch from the British Consulate in Jerusalem in 1839 reported that "the Jews of Algiers and its dependencies, are numerous in Palestine. . . ." There was also significant migration from Central Asia (Bukharan Jews

Bukharan Jews

Bukharan Jews, also Bukharian Jews or Bukhari Jews, or яҳудиёни Бухоро Yahūdieni Bukhoro , Bukhori Hebrew Script: יהודיאני בוכאראי and יהודיאני בוכארי), also called the Binai Israel, are Jews from Central Asia who speak Bukhori, a dialect of the Tajik-Persian language...

).

In addition to Messianic movements, the population of the Holy Land was slowly bolstered by Jews fleeing Christian persecution

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

especially after the Reconquista

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period of almost 800 years in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus...

of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

(the Muslim name of the Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

). Safed became an important center of Kabbalah

Kabbalah

Kabbalah/Kabala is a discipline and school of thought concerned with the esoteric aspect of Rabbinic Judaism. It was systematized in 11th-13th century Hachmei Provence and Spain, and again after the Expulsion from Spain, in 16th century Ottoman Palestine...

. Jerusalem, Hebron

Hebron

Hebron , is located in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judean Mountains, it lies 930 meters above sea level. It is the largest city in the West Bank and home to around 165,000 Palestinians, and over 500 Jewish settlers concentrated in and around the old quarter...

and Tiberias also had significant Jewish populations.

Aliyah and the ingathering of the exiles

Among Jews in the DiasporaJewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora is the English term used to describe the Galut גלות , or 'exile', of the Jews from the region of the Kingdom of Judah and Roman Iudaea and later emigration from wider Eretz Israel....

Eretz Israel was revered in a religious sense. They thought of a return to it in a future messianic age. Return remained a recurring theme among generations, particularly in Passover

Passover

Passover is a Jewish holiday and festival. It commemorates the story of the Exodus, in which the ancient Israelites were freed from slavery in Egypt...

and Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur , also known as Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most solemn day of the year for the Jews. Its central themes are atonement and repentance. Jews traditionally observe this holy day with a 25-hour period of fasting and intensive prayer, often spending most of the day in synagogue...

prayers which traditionally concluded with, "Next year in Jerusalem", and in the thrice-daily Amidah

Amidah

The Amidah , also called the Shmoneh Esreh , is the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy. This prayer, among others, is found in the siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer book...

(Standing prayer).

Jewish daily prayers include many references to "your people Israel", "your return to Jerusalem" and associate salvation with a restored presence in Israel and Jerusalem (usually accompanied by a Messiah); for example the prayer Uva Letzion

Uva Letzion

Uva letzion are the Hebrew opening words, and colloquially the name, of the closing prayer of the weekday morning service, before which one should not leave the synagogue...

(Isiah 59"20): "And a redeemer shall come to Zion..." Aliyah (immigration to Israel) has always been considered a praiseworthy act for Jews according to Jewish law

Halakha

Halakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

and some Rabbis consider it one of the core 613 commandments

613 mitzvot

The 613 commandments is a numbering of the statements and principles of law, ethics, and spiritual practice contained in the Torah or Five Books of Moses...

in Judaism. From the Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

and onwards, many famous rabbis (and often their followers) immigrated to the Land of Israel. These included Nahmanides

Nahmanides

Nahmanides, also known as Rabbi Moses ben Naḥman Girondi, Bonastruc ça Porta and by his acronym Ramban, , was a leading medieval Jewish scholar, Catalan rabbi, philosopher, physician, kabbalist, and biblical commentator.-Name:"Nahmanides" is a Greek-influenced formation meaning "son of Naḥman"...

, Yechiel of Paris

Yechiel of Paris

Yechiel ben Joseph of Paris was a major Talmudic scholar and Tosafist from northern France, father-in-law of Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil. He was a disciple of Rabbi Judah Messer Leon, and succeeded him in 1225 as head of the Yeshiva of Paris, which then boasted some 300 students; his best known...

with several hundred of his students, Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk

Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk

Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk , also known as Menachem Mendel of Horodok, was an early leader of Hasidic Judaism. Part of the third generation of Hasidic leaders, he was the primary disciple of the Maggid of Mezeritch...

and 300 of his followers, and over 500 disciples (and their families) of the Vilna Gaon

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Shlomo Zalman Kramer, known as the Vilna Gaon or Elijah of Vilna and simply by his Hebrew acronym Gra or Elijah Ben Solomon, , was a Talmudist, halachist, kabbalist, and the foremost leader of non-hasidic Jewry of the past few centuries...

known as Perushim

Perushim

The Perushim were disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, then under Ottoman rule...

, among others.

Persecution of the Jews

Persecution of Jews played a key role in preserving Jewish identity and keeping Jewish communities transient, it would later provide a key role in inspiring Zionists to reject European forms of identity.Jews in Catholic states were banned from owning land and from pursuing a variety of professions. From the 13th century Jews were required to wear identifying clothes such as special hats or stars on their clothing

Yellow badge

The yellow badge , also referred to as a Jewish badge, was a cloth patch that Jews were ordered to sew on their outer garments in order to mark them as Jews in public. It is intended to be a badge of shame associated with antisemitism...

. This form of persecution originated in tenth century Baghdad and was copied by Christian rulers. Constant expulsions and insecurity led Jews to adopt artisan professions that were easily transferable between locations (such as furniture making or tailoring).

Persecution in Spain and Portugal led large number of Jews there to convert to Christianiy, however many continued to secretly practice Jewish

Marrano

Marranos were Jews living in the Iberian peninsula who converted to Christianity rather than be expelled but continued to observe rabbinic Judaism in secret...

rituals. The Church responded by creating the Inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

in 1478 and by expelling all remaining Jews in 1492

Alhambra decree

The Alhambra Decree was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ordering the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Spain and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.The edict was formally revoked on 16 December 1968, following the Second...

. In 1542 the inquisition expanded to include the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

. Inquisitors could arbitrarily torture suspects and many victims were burnt alive.

In 1516 the state of Venice decreed that Jews would only be allowed to reside in a walled area adjacent to Venice

Venetian Ghetto

The Venetian Ghetto was the area of Venice in which Jews were compelled to live under the Venetian Republic. It is from its name in Italian , that the English word "ghetto" is derived: in the Venetian language it was named "ghèto".-Etymology:...

called the Ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

. Ghetto residents had to pay a daily poll tax

Poll tax

A poll tax is a tax of a portioned, fixed amount per individual in accordance with the census . When a corvée is commuted for cash payment, in effect it becomes a poll tax...

and could only stay a limited amount of time. In 1555 the Pope decreed that Jews in Rome were to face similar restrictions. The requirement for Jews to live in Ghettos spread across Europe and Ghettos were frequently highly overcrowded and heavily taxed. They also provided a convenient target for mobs (pogrom

Pogrom

A pogrom is a form of violent riot, a mob attack directed against a minority group, and characterized by killings and destruction of their homes and properties, businesses, and religious centres...

).

Jews were expelled from England

Edict of Expulsion

In 1290, King Edward I issued an edict expelling all Jews from England. Lasting for the rest of the Middle Ages, it would be over 350 years until it was formally overturned in 1656...

in 1290. A ban remained in force that was only lifted when Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

overthrew

English Civil War