.gif)

History of Poland (1939–1945)

Encyclopedia

Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland can refer to:* the second phase of the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 when Soviet armies marched on Warsaw, Poland* Soviet invasion of Poland of 1939 when Soviet Union allied with Nazi Germany attacked Second Polish Republic...

through to the end of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. On 1 September 1939, without a formal declaration of war

Declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one nation goes to war against another. The declaration is a performative speech act by an authorized party of a national government in order to create a state of war between two or more states.The legality of who is competent to declare war varies...

, Germany invaded Poland. Germany's immediate pretext was the Gleiwitz incident

Gleiwitz incident

The Gleiwitz incident was a staged attack by Nazi forces posing as Poles on 31 August 1939, against the German radio station Sender Gleiwitz in Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia, Germany on the eve of World War II in Europe....

, a provocation staged by the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

claiming that Polish troops had allegedly committed "provocations" along the German-Polish border including house torching, which were all staged by the Germans. Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

also used issues like the dispute between Germany and Poland over German rights to the Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

and the freeing of a passage between East Prussia and the rest of Germany through the Polish Corridor

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia , which provided the Second Republic of Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East...

as excuses for the invasion. Pursuant to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

, Poland was attacked by the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

on 17 September 1939. Before the end of the month most of Poland was divided between Germany and the Soviets.

German and Soviet invasions

The Nazi German invasion was anticipated already since the late thirties in the Polish army order of battle in 1939Polish army order of battle in 1939

Polish OOB during the Invasion of Poland. In the late thirties Polish headquarters prepared "Plan Zachód" , a plan of mobilization of Polish Army in case of war with Germany...

, but the strategic position of the Polish armed forces

Polish Armed Forces

Siły Zbrojne Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej are the national defense forces of Poland...

to resist was nevertheless hopeless, because Poland was surrounded on three sides by the German territories: Pomerania

Pomerania

Pomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

, Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

, East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

(all parts of Germany), and German-controlled Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. The newly formed Slovak State assisted their German allies by attacking Poland from the south. The Soviet Union encroached from the east, and finally Polish forces were blockaded on the Baltic Coast by the German and Soviet navies. The German "concept of annihilation" (Vernichtungsgedanke

Vernichtungsgedanke

Vernichtungsgedanke, literally meaning "concept of annihilation" in German and generally taken to mean "the concept of fast annihilation of enemy forces" is a tactical doctrine dating back to Frederick the Great. It emphasizes rapid, fluid movement to unbalance an enemy, allowing the attacker to...

) that later evolved into the Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg

For other uses of the word, see: Blitzkrieg Blitzkrieg is an anglicized word describing all-motorised force concentration of tanks, infantry, artillery, combat engineers and air power, concentrating overwhelming force at high speed to break through enemy lines, and, once the lines are broken,...

("lightning war") provided for rapid advance of Panzer

Panzer

A Panzer is a German language word that, when used as a noun, means "tank". When it is used as an adjective, it means either tank or "armoured" .- Etymology :...

(armoured) divisions, dive bombing (to break up troop concentrations), and aerial bombing of undefended cities to sap civilian morale. The Polish Army and Air Force had insufficient new equipment to match the onslaught.

German forces were numerically and technologically superior to Polish armed forces. The Germans threw 85% of their armed forces at Poland. They commanded 1.6 million men, 250,000 trucks and other motor vehicles, 11,000 artillery pieces, 2,500 tanks and a cavalry division. Some of the Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

pilots were the veterans of the elite Condor Legion

Condor Legion

The Condor Legion was a unit composed of volunteers from the German Air Force and from the German Army which served with the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legion developed methods of terror bombing which were used widely in the Second World War...

, which had seen action during the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

(1936–39). The Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

comprised 1,180 fighter aircraft (mainly Messerschmitt Bf 109

Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109, often called Me 109, was a German World War II fighter aircraft designed by Willy Messerschmitt and Robert Lusser during the early to mid 1930s...

s), 290 Ju 87 Stuka

Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka was a two-man German ground-attack aircraft...

dive bombers, 290 conventional bombers (mainly He 111 type), and 240 assorted naval aircraft. The German navy positioned its old battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

to shell Westerplatte

Westerplatte

Westerplatte is a peninsula in Gdańsk, Poland, located on the Baltic Sea coast mouth of the Dead Vistula , in the Gdańsk harbour channel...

, a section of Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

, an exclave separate from the main city and awarded to Poland by Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

in 1919.

The Polish forces found themselves severely outnumbered and outclassed. They consisted of 800,000 troops, including 11 cavalry brigades, two motorized brigades, 4,000 artillery pieces, and 880 tanks: 120 of them of the advanced 7-TP-type. The Polish airforce included 400 fighter aircraft: 160 PZL P.11

PZL P.11

The PZL P.11 was a Polish fighter aircraft, designed in the early 1930s by PZL in Warsaw. It was briefly considered to be the most advanced fighter aircraft design in the world...

c fighter aircraft, 31 PZL P.7

PZL P.7

-References:NotesBibliography* Cynk, Jerzy B. History of the Polish Air Force 1918-1968. Reading, Berkshire, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 1972.* Cynk, Jerzy B. Polish Aircraft, 1893-1939. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1971. ISBN 0-370-00085-4....

a and 20 P.11a fighters, 120 PZL.23 Karaś

PZL.23 Karas

|-Specifications :-See also:-References:NotesBibliography* Angelucci, Enzo and Paolo Matricardi. World War II Airplanes . Chicago: Rand McNally, 1978. ISBN 0-52888-170-1....

reconnaissance-bombers, and 45 PZL.37 Łoś medium bombers. The navy that did not participate in the withdrawal to United Kingdom and the linking up with the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

(known as Peking Plan

Peking Plan

The Peking PlanThe "Peking" in the name is the traditional English spelling of the former name of the city that is now the capital of China, which is now spelled in the pinyin system 'Beijing'. At the time, the city was not the capital, and its name was Peiping. Before the Second World War in the...

), consisted of four destroyers, one torpedo boat, one minelayer, two gunboats, six minesweepers, and five submarines.

The Poles believed that the invasion was intended from the beginning as a war of extermination. Hitler allegedly said to his commanders: "I have issued the command — and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad — that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formations in readiness — for the present only in the East — with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish race and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?" (There are some doubts about the authenticity of this quotation; see Armenian quote

Armenian quote

The Armenian quote is a paragraph understood to have been included in a speech by Adolf Hitler to Wehrmacht commanders at his Obersalzberg home on August 22, 1939, a week before the German invasion of Poland...

.)

Although the UK and France declared war on Germany, no direct military action was rendered. France was in direct violation of the Franco-Polish Military Alliance

Franco-Polish Military Alliance

The Franco-Polish alliance was the military alliance between Poland and France that was active between 1921 and 1940.-Background:Already during the France-Habsburg rivalry that started in the 16th century, France had tried to find allies to the east of Austria, namely hoping to ally with Poland...

that was signed in 19 May 1939, where France promised to attack Germany if Poland was attacked. Great Britain also refused to attack Germany, even though they had sworn to do so in the case of a German invasion. The Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

was tied up in the attack on Poland, and the French Army enjoyed decisive numerical advantage on their border with Germany, but the Allies failed to contribute solid assistance. Nine divisions of the French army (out of 102 that were ready for action) entered the German area in Saarland

Saarland

Saarland is one of the sixteen states of Germany. The capital is Saarbrücken. It has an area of 2570 km² and 1,045,000 inhabitants. In both area and population, it is the smallest state in Germany other than the city-states...

. They advanced only to a depth of eight kilometers and took over about 20 abandoned villages, without any resistance. The Saar Offensive

Saar Offensive

The Saar Offensive was a French operation into Saarland on the German 1st Army defence sector in the early stages of World War II. The purpose of the attack was to assist Poland, which was then under attack...

caused no German soldiers to be brought from Poland to the west. At the same time, the British Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

limited itself to dropping pamphlet

Pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound booklet . It may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths , or it may consist of a few pages that are folded in half and saddle stapled at the crease to make a simple book...

s on German cities. Shortly after their attack, the French General Staff ordered a retreat from German territory; and, on October 4 the French forces returned to their original positions. Many historians believe that, had the Great Britain and France honoured their pledge to Poland, the Nazis would have been contained and the war would not have had such a devastating impact on all European nations.

In the meanwhile, to the east of Poland, the Soviet Union was preparing its own military advance to occupy the eastern part of Poland in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

concluded between the USSR and Germany in August 1939, just weeks before the German invasion.

With Britain and France unwilling to follow on their military commitment to Poland, the Soviet Union, having its own reasons to fear the German expansionism further East, made various offers to Poland of an anti-German alliance, similar to the earlier one made to Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. Regardless of Stalin's true intentions, such alliances backed by the Soviet military force would have been a likely deterrent to Hitler's plans. However, the Poles feared Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's Communism nearly as much as they feared Hitler's Nazism, and throughout 1939 they refused to agree to any arrangement which would allow Soviet troops to freely enter Poland. The Polish refusal to accept the Soviet offer is best illustrated by the famous quote of Marshall Edward Rydz-Śmigły, the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish armed forces, who is quoted to have said: "With the Germans we run the risk of losing our liberty. With the Russians we will lose our soul". The Soviets then turned to concluding the treaty with Germany (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

) which was signed in August 1939.

The Polish government feared that Germany would launch only a limited war, to seize the territories which it claimed, and then ask France and Britain for a ceasefire. To defend these territories, the Polish military command compounded their strategic weakness by massing their forces along their western border, in defence of Poland's main industrial areas around Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

and Łódź, where they could be easily surrounded and cut off. By the time the Polish command decided to withdraw to the line of the Vistula

Vistula

The Vistula is the longest and the most important river in Poland, at 1,047 km in length. The watershed area of the Vistula is , of which lies within Poland ....

, it was too late. By 28 September, Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

was surrounded.

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

, Germany asked the Soviet Union on 3 September to engage its troops against the Polish state. The Soviet Union assured Germany that the Red Army advance into Poland would soon follow under the pretext of aiding the Ukrainians and the Belarusians threatened by Germany.

On 17 September, the Red Army marched its troops into Poland, which the Soviet Union now claimed to be non-existent. Also, concerns about the Soviets' own security were used to justify the invasion. The Red Army advance was coordinated with the movement of the German forces and met little resistance from the Polish forces (such as Battle of Szack

Battle of Szack

Battle of Szack was one of the major battles between the Polish Army and the Red Army fought in 1939 in the beginning the Second World War.- Eve of the Battle :...

fought by the Border Defence Corps or Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza), who were ordered to avoid engagement into the armed fights with the Soviets although some fighting between Soviet and Polish units took place.

The Polish government and high command retreated to the southeast Romanian bridgehead

Romanian Bridgehead

The Romanian Bridgehead was an area in southeastern Poland, now located in Ukraine. During the Polish Defensive War of 1939 , on September 14 the Polish Commander in Chief Marshal of Poland Edward Rydz-Śmigły ordered all Polish troops fighting east of the Vistula to withdraw towards Lwów, and...

and eventually crossed into neutral Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

. There was no formal surrender, and resistance continued in many places. Warsaw was bombed into submission, (the event that served as a trigger for the surrender was an accidental damage caused by one of the German bombs to the water supply system and subsequent lack of water) on 27 September, and some Army units fought until well into October (Battle of Kock

Battle of Kock (1939)

The Battle of Kock, was the final battle in the Invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II. It took place between 2–5 October 1939, near the town of Kock, in Poland....

). In the more mountainous parts of the country, Army units began underground resistance almost at once. The Polish army lost 65,000 troops, 400 air crew, and 110 navy crew. The German losses were 16,000 troops, 365 air crew, and 126 navy crew. 285 German aircraft were destroyed, with 126 claimed by Polish fighter pilots. Ninety were shot down by anti-aircraft fire, and, due to the modesty of Polish pilots, there is a deficit of 70 unclaimed kills. Three hundred more German aircraft were so badly damaged they were written off. The Polish Air Force lost 327 aircraft, 260 of which were lost due to direct or indirect enemy action, with around 70 in air-to-air fighting. Anti-aircraft fire claimed the other 67.

Occupation and dismemberment of Poland

About of Polish citizens lost their lives in the war, most of the civilians targeted by various deliberate actions. The German plan involved not only the annexation of Polish territory, but also the total destruction of Polish culture and the Polish nation (Generalplan OstGeneralplan Ost

Generalplan Ost was a secret Nazi German plan for the colonization of Eastern Europe. Implementing it would have necessitated genocide and ethnic cleansing to be undertaken in the Eastern European territories occupied by Germany during World War II...

).

Treatment of Polish citizens under German occupation

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

, such as the Polish Corridor

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia , which provided the Second Republic of Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East...

, West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

and Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

, but also a large area of indisputably Polish territory east of these territories, including the city of Łódź.

The Germans provided for the division of the annexed areas of Poland into the following administrative units:

- Reichsgau WarthelandReichsgau WarthelandReichsgau Wartheland was a Nazi German Reichsgau formed from Polish territory annexed in 1939. It comprised the Greater Poland and adjacent areas, and only in part matched the area of the similarly named pre-Versailles Prussian province of Posen...

(initially Reichsgau PosenPoznanPoznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

), which included the entire Poznań voivodship, most of the Łódź voivodship, five counties of the PomeraniaPomeraniaPomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

n voivodship, and one county of the WarsawWarsawWarsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

voivodship; - the remaining area of Pomeranian voivodship, which was incorporated into the Reichsgau Danzig-Westpreussen (initially Reichsgau Westpreussen);

- CiechanówCiechanówCiechanów is a town in north-central Poland with 45,900 inhabitants . It is situated in Masovian Voivodeship . It was previously the capital of Ciechanów Voivodeship.-History:The grad numbered approximately 3,000 armed men....

District (Regierungsbezirk Zichenau) consisting of the five northern counties of Warsaw voivodship (Płock, Płońsk, SierpcSierpcSierpc is a town in Poland, in the north-west part of the Masovian Voivodeship, about 125 km northwest of Warsaw. It is the capital of Sierpc County. Its population is 18,777 . It is located near the national road No 10, which connects Warsaw and Toruń...

, Ciechanów and Mława), which became a part of East PrussiaEast PrussiaEast Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

; - Katowice District (Regierungsbezirk Kattowitz) or, unofficially, East Upper SilesiaUpper SilesiaUpper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

(Ost-Oberschlesien), which included Silesian Voivodeship, SosnowiecSosnowiecSosnowiec is a city in Zagłębie Dąbrowskie in southern Poland, near Katowice. It is one of the central districts of the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union - a metropolis with a combined population of over two million people located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Brynica river .It is situated in...

, BędzinBedzinBędzin is a city in Zagłębie Dąbrowskie in southern Poland. Located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Czarna Przemsza river , the city borders the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union - a metro area with a population of about 2 million.It has been situated in the Silesian Voivodeship since its...

, ChrzanówChrzanówChrzanów is a town in south Poland with 39,704 inhabitants . It is situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship and is the capital of Chrzanów County.- To 1809:...

, OświęcimOswiecimOświęcim is a town in the Lesser Poland province of southern Poland, situated west of Kraków, near the confluence of the rivers Vistula and Soła.- History :...

, and ZawiercieZawiercieZawiercie is a city in the Silesian Voivodeship of southern Poland with 55,800 inhabitants . It is situated in the Kraków-Częstochowa highland near the source of the Warta River...

Counties, and parts of OlkuszOlkuszOlkusz is a town in south Poland with 37,696 inhabitants . Situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship , previously in Katowice Voivodeship , it is the capital of Olkusz County...

and ŻywiecZywiecŻywiec is a town in south-central Poland with 32,242 inhabitants . Between 1975 and 1998, it was located within the Bielsko-Biała Voivodeship, but has since become part of the Silesian Voivodeship....

Counties, which became a part of Province of Upper SilesiaProvince of Upper SilesiaThe Province of Upper Silesia was a province of the Free State of Prussia created in the aftermath of World War I. It comprised much of the region of Upper Silesia and was eventually divided into two administrative regions , Kattowitz and Oppeln...

.

The area of these annexed territories was 94,000 square kilometres and the population was about 10 million, the great majority of whom were Poles.

Under the terms of the Nazi-Soviet pact, adjusted by agreement on 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union, annexed all Polish territory east of the line of the rivers Pisa, Narew

Narew

The Narew River , in western Belarus and north-eastern Poland, is a left tributary of the Vistula river...

, Bug

Bug River

The Bug River is a left tributary of the Narew river flows from central Ukraine to the west, passing along the Ukraine-Polish and Polish-Belarusian border and into Poland, where it empties into the Narew river near Serock. The part between the lake and the Vistula River is sometimes referred to as...

and San

San River

The San is a river in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine, a tributary of the Vistula River, with a length of 433 km and a basin area of 16,861 km2...

, except for the area around Vilnius

Vilnius

Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania, and its largest city, with a population of 560,190 as of 2010. It is the seat of the Vilnius city municipality and of the Vilnius district municipality. It is also the capital of Vilnius County...

(known in Polish as Wilno), which was given to Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, and the Suwałki region, which was annexed by Germany. These territories were largely inhabited by Ukrainians

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

and Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

ians, with minorities of Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

and Jews (see exact numbers in Curzon line

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was put forward by the Allied Supreme Council after World War I as a demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and Bolshevik Russia and was supposed to serve as the basis for a future border. In the wake of World War I, which catalysed the Russian Revolution of 1917, the...

). The total area, including the area given to Lithuania, was 201,000 square kilometres, with a population of 13.5 million. A small strip of land that was part of Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

before 1914, was also given to Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

.

After the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Polish territories previously occupied by the Soviet were organized as follows:

- Bezirk Białystok' (district of Białystok), which included the Białystok, Bielsk PodlaskiBielsk Podlaski-Roads and Highways:Bielsk Podlaski is at the intersection of two National Road and a Voivodeship Road:* National Road 19 - Kuźnica Białystoka Border Crossing - Kuźnica - Białystok - Bielsk Podlaski - Siemiatycze - Międzyrzec Podlaski - Kock - Lubartów - Lublin - Kraśnik - Janów Lubelski - Nisko...

, GrajewoGrajewoGrajewo , is a town in north-eastern Poland with 23,302 inhabitants .It is situated in the Podlaskie Voivodeship ; previously, it was in Łomża Voivodeship...

, Łomża, Sokółka, Volkovysk, and Grodno counties, was "attached" to (but not incorporated into) East Prussia; - Bezirke Litauen und Weißrussland — the Polish part of White Russia (today western BelarusBelarusBelarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

), including the Vilna province (VilniusVilniusVilnius is the capital of Lithuania, and its largest city, with a population of 560,190 as of 2010. It is the seat of the Vilnius city municipality and of the Vilnius district municipality. It is also the capital of Vilnius County...

was incorporated into the Reichskommissariat OstlandReichskommissariat OstlandReichskommissariat Ostland, literally "Reich Commissariat Eastland", was the civilian occupation regime established by Nazi Germany in the Baltic states and much of Belarus during World War II. It was also known as Reichskommissariat Baltenland initially...

); - Bezirk Wolhynien-Podolien — the Polish province of VolhyniaVolhyniaVolhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

, which was incorporated into the Reichskommissariat UkraineUkraineUkraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

; and - East Galicia, which was incorporated into the General-Government and became its fifth district.

The future fate of Poland and Poles was decided in Generalplan Ost

Generalplan Ost

Generalplan Ost was a secret Nazi German plan for the colonization of Eastern Europe. Implementing it would have necessitated genocide and ethnic cleansing to be undertaken in the Eastern European territories occupied by Germany during World War II...

, a Nazi plan to ethnically cleanse

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic orreligious group from certain geographic areas....

the territories occupied by Germany in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

. The remaining block of territory was placed under a German administration called the General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

(in German Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete), with its capital at Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

. The General Government was subdivided into four districts, Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, Lublin

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth largest city in Poland. It is the capital of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 350,392 . Lublin is also the largest Polish city east of the Vistula river...

, Radom

Radom

Radom is a city in central Poland with 223,397 inhabitants . It is located on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship , having previously been the capital of Radom Voivodeship ; 100 km south of Poland's capital, Warsaw.It is home to the biennial Radom Air Show, the largest and...

, and Kraków. (For more detail on the territorial division of this area see General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

.)

A German lawyer and prominent Nazi, Hans Frank

Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank was a German lawyer who worked for the Nazi party during the 1920s and 1930s and later became a high-ranking official in Nazi Germany...

, was appointed Governor-General of the occupied territories on 26 October. Frank oversaw the segregation of the Jews into ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

s in the larger cities, particularly Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, and the use of Polish civilians as forced and compulsory labour in German war industries.

The population in the General Government's territory was initially about 12 million in an area of 94,000 km², but this increased as about 860,000 Poles and Jews were expelled from the German-annexed areas and "resettled" in the General Government. Offsetting this was the German campaign of extermination of the Polish intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

and other elements thought likely to resist (e.g. Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg was the codename for one of the extermination actions directed at the Polish people during World War II, part of the Generalplan Ost...

and Action AB). From 1941, disease and hunger also began to reduce the population. Poles were also deported in large numbers to work as forced labour in Germany: eventually about a million were deported, and many died in Germany.

According to recent (2009) estimates by IPN

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance — Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation is a Polish government-affiliated research institute with lustration prerogatives and prosecution powers founded by specific legislation. It specialises in the legal and historical sciences and...

, between 5.62 million and 5.82 million Polish citizens (including Polish Jews) died as a result of the German occupation.

Treatment of Polish citizens under Soviet occupation

By the end of Polish Defensive War, the Soviet Union took over 52,1% of the territory of Poland (circa 200,000 km²), with over 13,700,000 people. Although estimates vary, the most thorough analysis gives the following numbers in regards to the ethnic composition of these areas: 38% Poles (ca. 5,1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14,5% Belarusians, 8,4% Jews, 0,9% Russians and 0,6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees from areas occupied by Germany, most of them Jews (198,000). Areas occupied by USSR were annexed to Soviet territoryPolish areas annexed by the Soviet Union

Immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II, the Soviet Union invaded the eastern regions of the Second Polish Republic, which Poles referred to as the "Kresy," and annexed territories totaling 201,015 km² with a population of 13,299,000...

, with the exception of area of Vilnius

Vilnius region

Vilnius Region , refers to the territory in the present day Lithuania, that was originally inhabited by ethnic Baltic tribes and was a part of Lithuania proper, but came under East Slavic and Polish cultural influences over time,...

, which was transferred to Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, although soon attached to USSR, when Lithuania

Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic , also known as the Lithuanian SSR, was one of the republics that made up the former Soviet Union...

became a Soviet republic

Republics of the Soviet Union

The Republics of the Soviet Union or the Union Republics of the Soviet Union were ethnically-based administrative units that were subordinated directly to the Government of the Soviet Union...

.

While Germans enforced their policies based on racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

, the Soviet administration used slogans about class struggle

Class struggle

Class struggle is the active expression of a class conflict looked at from any kind of socialist perspective. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote "The [written] history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle"....

, and dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

, which in Soviet reality were equal to Stalinism

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

and Sovietization

Sovietization

Sovietization is term that may be used with two distinct meanings:*the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets .*the adoption of a way of life and mentality modelled after the Soviet Union....

. Immediately after their conquest of eastern Poland, the Soviet authorities started a campaign of sovietization

Sovietization

Sovietization is term that may be used with two distinct meanings:*the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets .*the adoption of a way of life and mentality modelled after the Soviet Union....

of the newly-acquired areas. No later than several weeks after the last Polish units surrendered, on October 22, the Soviets organized staged elections

Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus

Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, which took place on October 22, 1939, were an attempt to legitimate territorial gains of the Soviet Union, at the expense of the Second Polish Republic...

to the Moscow-controlled Supreme Soviet

Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union was the Supreme Soviet in the Soviet Union and the only one with the power to pass constitutional amendments...

s (legislative body) of Western Belarus and Western Ukraine. The result of the staged voting was to become a legitimization of Soviet partition of Poland.

Subsequently, all institutions of the dismantled Polish state were being closed down and reopened with new mostly Russian directors and in rare cases Ukrainian or Polish ones. Lviv University

Lviv University

The Lviv University or officially the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv is the oldest continuously operating university in Ukraine...

and other schools restarted anew as Soviet institutions. Studies were simply devoted to Soviet propaganda. Polish literature and language studies were dissolved by Soviet authorities.

Simultaneously, Soviet authorities attempted to remove all signs of Polish existence in the area by eliminating much of what had any connection to the Polish state or even Polish culture in general, as well as removing the Polish population On 21 December, the Polish currency was withdrawn from circulation without any exchange to the newly-introduced rouble, which meant that the entire population of the area lost all of their life-time savings overnight. In schools, Polish language books were burned down.

All the media became controlled by Moscow. Soviet occupation implemented a political regime similar to police state

Police state

A police state is one in which the government exercises rigid and repressive controls over the social, economic and political life of the population...

, based on terror. All Polish parties and organisations were disbanded. Only the Communist Party

Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine is a political party in Ukraine, currently led by Petro Symonenko.The party fights the Ukrainian national self-determination by identifying any Ukrainian national parties as the National-Fascist ones The Communist Party of Ukraine is a political party in Ukraine,...

was allowed to exist with organisations subordinated to it. Soviet teachers in schools encouraged children to spy on their parents proposing money as bribes.

All organized religions were persecuted. Most churches were closed; priests and ministers were discriminated against by authorities regardless of their faith, with forms of discrimination including high taxes, forced drafts into military service, arrests and deportations. Children were told that they should pray to paintings of Stalin instead of the cross, and were rewarded with sweets and candy for this.

All enterprises were taken over by the state, while agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

was made collective

Collective farming

Collective farming and communal farming are types of agricultural production in which the holdings of several farmers are run as a joint enterprise...

. The results of Soviet economic policy were quickly seen, in winter locals faced new problems, as shops lacked goods, there was scarce food and they had to face famine

Famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including crop failure, overpopulation, or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every continent in the world has...

.

According to the Soviet law, all residents of the annexed area, dubbed by the Soviets as citizens of former Poland, automatically acquired Soviet citizenship. However, since actual conferral of citizenship still required the consent of the individual, residents were strongly pressured for such consent and the refugees who opted out were threatened with repatriation to Nazi controlled territories of Poland.

In addition, the Soviets exploited past ethnic tensions between Poles and other ethnic groups, inciting and encouraging violence against Poles by calling upon the minorities to "rectify the wrongs they had suffered during twenty years of Polish rule". Pre-war Poland was portrayed as a capitalist state based on exploitation of the working people and ethnic minorities. Soviet officials openly incited mobs to perform killings and robberies against the Polish population, going as far as stating that the Red Army would help to kill and pillage. A brutal bloodbath ensued. Such events made an everlasting influence on the Polish attitude towards Soviet occupation.

Some parts of the Ukrainian population initially welcomed the end of Polish rule. This was even strengthened by a land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

in which the owners of large lots of land were labeled "kulak

Kulak

Kulaks were a category of relatively affluent peasants in the later Russian Empire, Soviet Russia, and early Soviet Union...

s" and dispossessed of their land which was then divided among poorer peasants.

However, soon afterwards the Soviet authorities started a campaign of forced collectivisation, which largely nullified the earlier gains from the land reform as the peasants generally did not want to join the Kolkhoz

Kolkhoz

A kolkhoz , plural kolkhozy, was a form of collective farming in the Soviet Union that existed along with state farms . The word is a contraction of коллекти́вное хозя́йство, or "collective farm", while sovkhoz is a contraction of советское хозяйство...

farms, nor to give away their crops for free to fulfill the state imposed quotas. At the same time, there were large groups of pre-war Polish citizens, notably Jewish youth and, to a lesser extent, the Ukrainian peasants, who saw the Soviet power as an opportunity to start political or social activity outside of their traditional ethnic or cultural groups. Their enthusiasm however faded with time as it became clear that the Soviet repressions were aimed at all groups equally, regardless of their political stance. The organisation of Ukrainians desiring independent Ukraine (the OUN) was persecuted as "anti-soviet".

An inherent part of the Sovietization was a rule of terror started by the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

and other Soviet agencies. The first victims of the new order were approximately 250,000 Polish prisoners of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

captured by the USSR during and after the Polish Defensive War. As the Soviet Union did not sign any international convention on rules of war, they were denied the status of prisoners of war and instead almost all of the captured officers and a large number of ordinary soldiers were then murdered (see Katyn massacre

Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre , was a mass execution of Polish nationals carried out by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs , the Soviet secret police, in April and May 1940. The massacre was prompted by Lavrentiy Beria's proposal to execute all members of...

) or sent to Gulag

Gulag

The Gulag was the government agency that administered the main Soviet forced labor camp systems. While the camps housed a wide range of convicts, from petty criminals to political prisoners, large numbers were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas and other instruments of...

. Of the 10,000-12,000 Poles sent to Kolyma

Kolyma

The Kolyma region is located in the far north-eastern area of Russia in what is commonly known as Siberia but is actually part of the Russian Far East. It is bounded by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Sea of Okhotsk to the south...

in 1940–41, most POWs, only 583 men survived, released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East

Polish Armed Forces in the East

Polish Armed Forces in the East refers to military units composed of Poles created in the Soviet Union at the time when the territory of Poland was occupied by both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the Second World War....

. Out of Anders's 80,000 evacuees from Soviet Union gathered in Great Britain only 310 volunteered to return to Poland in 1947.

Similar policies were applied to the civilian population as well. The Soviet authorities regarded service for the pre-war Polish state as a "crime against revolution" and "counter-revolutionary activity", and subsequently started arresting large numbers of Polish intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

, politicians, civil servants and scientists, but also ordinary people suspected of posing a threat to the Soviet rule. Schoolchildren as young as 10 or 12 years old that laughed at Soviet propaganda presented in schools were sent into prisons, sometimes for as long as 10 years.

The prisons soon got severely overcrowded with detainees suspected of anti-Soviet activities and the NKVD had to open dozens of ad-hoc prison sites in almost all towns of the region. The wave of arrests led to forced resettlement of large categories of people (kulak

Kulak

Kulaks were a category of relatively affluent peasants in the later Russian Empire, Soviet Russia, and early Soviet Union...

s, Polish civil servants, forest workers, university professors or osadnik

Osadnik

Osadniks was the Polish loanword used in Soviet Union for veterans of the Polish Army that were given land in the Kresy territory ceded to Poland by Polish-Soviet Riga Peace Treaty of 1921 .-Colonization process:Shortly before the battle of Warsaw on August 7, 1920, the Premier of Poland,...

s, for instance) to the Gulag

Gulag

The Gulag was the government agency that administered the main Soviet forced labor camp systems. While the camps housed a wide range of convicts, from petty criminals to political prisoners, large numbers were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas and other instruments of...

labour camps. Altogether, roughly a half a million people were sent to the east in four major waves of deportations. Many of them were dead by the time the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement

Sikorski-Mayski Agreement

The Sikorski–Mayski Agreement was a treaty between the Soviet Union and Poland signed in London on 30 July 1941. Its name was coined after the two most notable signatories: Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Mayski.- Details :After signing...

had been signed in 1941.

According to recent (2009) estimates by IPN

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance — Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation is a Polish government-affiliated research institute with lustration prerogatives and prosecution powers founded by specific legislation. It specialises in the legal and historical sciences and...

, around 150,000 thousand Polish citizens died as a result of the Soviet occupation. Those estimates also suggest a much smaller number of deportees (around 320,000)..

Resistance in Poland

Resistance to the German occupation began almost at once, although there is little terrain in Poland suitable for guerrilla operations. The Home ArmyArmia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

(in Polish Armia Krajowa or AK), loyal to the Polish government in exile

Polish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

in London and a military arm of the Polish Secret State

Polish Secret State

The Polish Underground State is a collective term for the World War II underground resistance organizations in Poland, both military and civilian, that remained loyal to the Polish Government in Exile in London. The first elements of the Underground State were put in place in the final days of the...

, was formed from a number of smaller groups in 1942. From 1943, the AK was in competition with the People's Army

People's Army

People's Army was a title of several communist armed forces:* Czechoslovak People's Army* People's Army of Poland* Vietnam People's Army* National People's Army, of East Germany* Yugoslav People's Army* Korean People's Army...

(Polish Armia Ludowa or AL), backed by the Soviet Union and controlled by the Polish Workers' Party

Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland, and merged with the Polish Socialist Party in 1948 to form the Polish United Workers' Party.-History:...

(Polish Polska Partia Robotnicza or PPR). By 1944, the AK had some 380,000 men, although few arms: the AL was much smaller.

In August 1943 and March 1944, the Polish Secret State announced their long-term plan, partially designed to counter attractivness of some of the Communists' proposals. Their plan promised land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

, nationalisation of the industrial base, demands for territorial compensation from Germany, as well as re-establishment of the pre-1939 eastern border. Thus, the main difference between the Secret State and the Communists, in terms of politics, amounted not to radical economic and social reforms, which were advocated by both sides, but to their attitudes towards national sovereignty, borders, and Polish-Soviet relations.

In April 1943, the Germans began deporting the remaining Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

, provoking the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the Jewish resistance that arose within the Warsaw Ghetto in German occupied Poland during World War II, and which opposed Nazi Germany's effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to Treblinka extermination camp....

from 19 April-16 May one of the first armed uprisings against the Germans in Poland. The Polish-Jewish leaders knew that the rising would be crushed but they preferred to die fighting than wait to be deported to their deaths in the camps.

In 1943, the Home Army built up its forces in preparation for a national uprising. The plan was code-named Operation Tempest

Operation Tempest

Operation Tempest was a series of uprisings conducted during World War II by the Polish Home Army , the dominant force in the Polish resistance....

and began in late 1943. Its most widely known elements were Operation Ostra Brama and the Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

. In August 1944, as the Soviet armed forces approached Warsaw, the government in exile called for an uprising in the city, so that they could return to a liberated Warsaw and try to prevent a Communist takeover. The AK, led by Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski

Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski

General Count Tadeusz Komorowski , better known by the name Bór-Komorowski was a Polish military leader....

, launched the Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

. Soviet forces were less than 20 km (12.4 mi) away, but on the orders of Soviet High Command, they gave little assistance. Stalin described the rising as a "criminal adventure." The Poles appealed for the western Allies for help. The Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

, and the Polish Air Force based in Italy, dropped some arms but, as in 1939, it was almost impossible for the Allies to help the Poles without Soviet assistance.

The fighting in Warsaw was desperate, with selfless valour being displayed in street-to-street fighting. The AK had between 12,000 and 20,000 armed soldiers, most with only small arms, against a well-equipped German Army of 20,000 SS and regular Army units. Bór-Komorowski's hope that the AK could take and hold Warsaw for the return of the London government was never likely to be achieved. After 63 days of savage fighting, the city was reduced to rubble, and German reprisals were savage. The SS and auxiliary units recruited from Soviet Army deserters were particularly brutal.

After Bór-Komorowski's surrender, the AK fighters were treated as prisoners-of-war by the Germans, much to the outrage of Stalin, but the civilian population were ruthlessly punished. Overall, Polish casualties are estimated to be between 150,000 and 300,000 killed, with 90,000 civilians being sent to labour camps in the Reich

Reich

Reich is a German word cognate with the English rich, but also used to designate an empire, realm, or nation. The qualitative connotation from the German is " sovereign state." It is the word traditionally used for a variety of sovereign entities, including Germany in many periods of its history...

, while 60,000 were shipped to death and concentration camps such as Ravensbrück, Auschwitz, Mauthausen

Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

Mauthausen Concentration Camp grew to become a large group of Nazi concentration camps that was built around the villages of Mauthausen and Gusen in Upper Austria, roughly east of the city of Linz.Initially a single camp at Mauthausen, it expanded over time and by the summer of 1940, the...

, and others. The city was almost totally destroyed after German bombers systematically demolished the city. The Warsaw Rising allowed the Germans to destroy the AK as a fighting force, but the main beneficiary was Stalin, who was able to impose a Communist government on postwar Poland with little fear of armed resistance.

Rare instances of collaboration with the occupiers

Polish resistance movement in World War II

The Polish resistance movement in World War II, with the Home Army at its forefront, was the largest underground resistance in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, covering both German and Soviet zones of occupation. The Polish defence against the Nazi occupation was an important part of the European...

was the largest in all of occupied Europe. As a result, Polish citizens were unlikely to be given positions of any significant authority. The vast majority of the pre-war citizenry collaborating with the Nazis was the German minority in Poland

German minority in Poland

The registered German minority in Poland consists of 152,900 people, according to a 2002 census.The German language is used in certain areas in Opole Voivodeship , where most of the minority resides...

which was offered one of several possible grades of the German citizenship (Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche - "German in terms of people/folk" -, defined ethnically, is a historical term from the 20th century. The words volk and volkische conveyed in Nazi thinking the meanings of "folk" and "race" while adding the sense of superior civilization and blood...

). During the war there were about 3 million former Polish citizens of German origin who signed the official list of the Volksdeutsche. People who became Volksdeutsche were treated by Poles with special contempt, and the fact of them having signed the Volksliste

Volksliste

The Deutsche Volksliste was a Nazi institution whose purpose was the classification of inhabitants of German occupied territories into categories of desirability according to criteria systematized by Heinrich Himmler. The institution was first established in occupied western Poland...

constituted high treason according to the Polish underground law.

Depending on a definition of collaboration (and of a Polish citizen, based on ethnicity and minority status), scholars estimate number of "Polish collaborators" at around several thousand in a population of about 35 million (that number is supported by the Israeli War Crimes Commission). The estimate is based primarily on the number of death sentences for treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

by the Special Courts

Special Courts

Special Courts were the underground courts organized by the Polish Government in Exile during World War II in occupied Poland. The courts determined punishments for the citizens of Poland who were subject to the Polish law before the war.-History:After the Polish Defense War of 1939...

of the Polish Underground State. John Connelly quoted a Polish historian (Leszek Gondek) calling the phenomenon of Polish collaboration "marginal" and wrote that "only relatively small percentage of Polish population engaged in activities that may be described as collaboration when seen against the backdrop of European and world history".

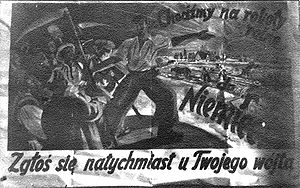

In October 1939, the Nazis ordered the mobilization

Mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and making both troops and supplies ready for war. The word mobilization was first used, in a military context, in order to describe the preparation of the Prussian army during the 1850s and 1860s. Mobilization theories and techniques have continuously changed...

of the pre-war Polish police to the service of the occupational authorities. The policemen were to report for duty or face death penalty. Blue Police

Blue Police

The Blue Police, more correctly translated as The Navy-Blue Police was the popular name of the collaborationist police in the German occupied area of the Second Polish Republic, known as General Government during the Second World War...

was formed. At its peak in 1943, it numbered around 16,000. Its primary task was to act as a regular police

Police

The police is a personification of the state designated to put in practice the enforced law, protect property and reduce civil disorder in civilian matters. Their powers include the legitimized use of force...

force and to deal with criminal activities, but were also used by the Germans in combating smuggling, and patrolling the ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

s. Nonetheless many individuals in the Blue Police followed German orders reluctantly, often disobeyed German orders or even risked death acting against them. Many members of the Blue Police were in fact double agent

Double agent

A double agent, commonly abbreviated referral of double secret agent, is a counterintelligence term used to designate an employee of a secret service or organization, whose primary aim is to spy on the target organization, but who in fact is a member of that same target organization oneself. They...

s for the Polish resistance. Some of its officers were ultimately awarded the Righteous among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous among the Nations of the world's nations"), also translated as Righteous Gentiles is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis....

awards for saving Jews.

Following Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

in June 1941, German forces quickly overran the territory of Poland controlled by the Soviets since their joint invasion. However, there are no known joint Polish-German actions, and the Germans were unsuccessful in their attempt to turn the Poles toward fighting exclusively against Soviet partisans.Tadeusz Piotrowski

Tadeusz Piotrowski (sociologist)

Tadeusz Piotrowski or Thaddeus Piotrowski is a Polish-American sociologist. He is a Professor of Sociology in the Social Science Division of the University of New Hampshire at Manchester in Manchester, New Hampshire, where he lives....

quotes Joseph Rothschild

Joseph Rothschild

Joseph Rothschild was an American Jewish professor of history and political science at Columbia University, specializing in Central European and Eastern European history....

saying "The Polish Home Army was by and large untainted by collaboration" and adds that "the honor of AK as a whole is beyond reproach". In 1944, Germans clandestinely armed a few regional Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

(AK) units operating in the area of Vilnius

Vilnius

Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania, and its largest city, with a population of 560,190 as of 2010. It is the seat of the Vilnius city municipality and of the Vilnius district municipality. It is also the capital of Vilnius County...

in order to encourage them to act against the Soviet partisans

Soviet partisans in Poland

Poland was annexed and partitioned by Germany and the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the invasion of Poland in 1939. In the pre-war Polish territories annexed by the Soviets the first Soviet partisan groups were formed in 1941, soon after Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet...

in the region; in Nowogrodek district and to a lesser degree in Vilnius district (AK turned these weapons against the Nazis during Operation Ostra Brama). Such arrangements were purely tactical and did not evidence the type of ideological collaboration as shown by Vichy regime in France or Quisling regime

Quisling regime

The Quisling regime, or the Quisling government are common names used to refer to the collaborationist government led by Vidkun Quisling in occupied Norway during the Second World War. The official name of the regime from 1 February 1942 until its dissolution in May 1945 was Nasjonale regjering...

in Norway. The Poles main motivation was to gain intelligence on German morale and preparedness and to acquire much needed equipment.

Gunnar S. Paulsson

Gunnar S. Paulsson

Gunnar Svante Paulsson is a Swedish-born Canadian historian who has taught in Britain and Canada.Paulsson graduated Oxford University with a D.Phil. in 1998...

estimates that in Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

the number of Polish citizens collaborating with the Nazis during occupation might have been around "1 or 2 percent" (p. 113). However, the damage that these criminals did was substantial. Most were interested in money. Blackmailers significantly increased the danger facing Jews and their chances of getting caught and killed. They harassed rescuers, stripped Jews of assets needed for food and bribes, raised the overall level of insecurity, and forced hidden Jews to seek out safer accommodations. Some individuals took advantage of a hiding person's desperation by collecting money, then reneging on their promise of aid—or worse, turning them over to the Germans for an additional reward. Individuals who turned in Jews in hiding to the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

received a standard payment consisting of some cash, liquor, sugar and cigarettes. Many Jews were robbed and handed over to the Germans by "szmalcownik

Szmalcownik

Szmalcownik is a pejorative Polish slang word used during World War II that denoted a person blackmailing Jews who were hiding, or blackmailing Poles who protected Jews during the Nazi occupation...

"s many of whom practiced blackmail as an "occupation". Those criminals were condemned by the Polish Underground State and a fight against these informers was organized by Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

(Underground State's military arm), with the death sentence being meted out on a scale unknown in the occupied countries of Western Europe.

A number of people collaborating with the Soviet NKVD

NKVD