History of New South Wales

Encyclopedia

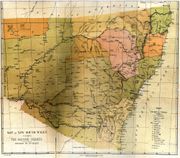

The history of New South Wales refers to the history of the Australia

n State of New South Wales

and its preceding Indigenous and British colonial societies. The Mungo Lake remains indicate occupation of New South Wales by Aboriginal Australians for at least 40,000 years. The English navigator James Cook

became the first European to map the coast in 1770 and a First Fleet

of British convicts followed to establish a penal colony

at Sydney

in 1788. The colony established an autonomous Parliamentary democracy from the 1840s and became a state

of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 following a vote to Federate with the other British colonies of Australia. Through the 20th century, the state was a major destination for an increasingly diverse collection of migrants from many nations. In the 21st century, the state is the most populous in Australia, and its capital, Sydney is a major financial capital and host to international cultural and economic events.

The first people to occupy the area now known as New South Wales were Australian Aborigines

. Their presence in Australia began around 40,000–60,000 years ago with the arrival of the first of their ancestors by boat from what is now Indonesia

. Their descendants moved south and, though never large in numbers, occupied all areas of Australia, including the future New South Wales.

Mungo Man and other remains have been found at the dried up Lake Mungo

in New South Wales, some 3000 km south of the North Coast of Australia, and have been dated to approximately 40,000 years ago. These early humans appear to have been buried with ceremonial accompaniment and have been found close to stone tools and the bones of now extinct mega fauna (such as giant kangaroos and wombats). These are the earliest human remains yet found in Australia, though precise dating is difficult and debated. They nevertheless appear to confirm that New South Wales was populated some tens of thousands of years before the arrival of the British First Fleet

at a time when the climate was far wetter and humans were conducting some of their earliest religious and artistic practices. Examples of Aboriginal stone tools and Aboriginal art (often recording the stories of the Dreamtime

religion) can be found throughout New South Wales: even within the metropolis of modern Sydney, as in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

.

, in command of the HMS Endeavour

, sailed along the east coast of Australia

, becoming the first known Europeans to do so. On 19 April 1770, the crew of the Endeavour sighted the east coast of Australia and ten days later landed at a bay in what is now southern Sydney. The ship's naturalist, Sir Joseph Banks

, was so impressed by the volume of flora and fauna hitherto unknown to European science, that Cook named the inlet Botany Bay

. Cook charted the East coast to its northern extent and, on 22 August, at Possession Island in the Torres Strait

, Cook wrote in his journal: "I now once more hoisted English Coulers [sic] and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third

, took possession of the whole Eastern Coast from the above Latitude 38°S

down to this place by the name of New South Wales

." Cook and Banks then reported favourably to London on the possibilities of establishing a British colony at Botany Bay.

Britain thereby became the first European power to officially claim any area on the Australian mainland. "New South Wales", as defined by Cook's proclamation, covered most of eastern Australia, from 38°S 145°E (near the later site of Mordialloc, Victoria

), to the tip of Cape York

, with an unspecified western boundary. By implication, the proclamation excluded: Van Diemen's Land

(later Tasmania), which had been claimed for the Netherlands

by Abel Tasman

in 1642; a small part of the mainland south of 38° (later southern Victoria) and; the west coast of the continent

(later Western Australia), which Louis de Saint Aloüarn

officially claimed for France

in 1772 — even though it had been mapped previously by Dutch mariners.

The British claim remained theoretical until January 1788, when Arthur Phillip

The British claim remained theoretical until January 1788, when Arthur Phillip

arrived with the First Fleet

to found a convict settlement at what is now Sydney

. Phillip, as Governor of New South Wales, exercised nominal authority over all of Australia east of the 135th meridian east

between the latitudes of 10°37'S and 43°39'S, which included most of New Zealand

except for the southern part of South Island

.

The First Fleet

The First Fleet

of 11 vessels consisted of over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts (192 women and 586 men). A few days after arrival at Botany Bay

the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson

where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove

on 26 January 1788. This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day

. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and a safe harbour, which Philip famously described as:

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Enlightened for his Age, Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers - most notably Watkin Tench

– left behind journals and accounts of which tell of immense hardships during the first years of settlement. Often Phillip's officers despaired for the future of New South Wales. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were few and far between. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney – many "professional criminals" with few of the skills required for the establishment of a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick or unfit for work and the conditions of healthy convicts only deteriorated with hard labour and poor sustenance in the settlement. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its 'passengers' through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791 however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils and fixed on the Parramatta region as a promising area for expansion and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life, leaving Sydney Cove as an important port and focus of social life. Poor equipment and unfamiliar soils and climate continued to hamper the expansion of farming from Farm Cove to Parramatta and Toongabbie, but a building programme, assisted by convict labour, advanced steadily. Between 1788–92, convicts and their gaolers made up the majority of the population - but after this, a population of emancipated convicts began to grow who could be granted land and these people pioneered a non-government private sector economy and were later joined by soldiers whose military service had expired - and finally, free settlers who began arriving from Britain. Governor Phillip departed the colony for England on 11 December 1792, with the new settlement having survived near starvation and immense isolation for four years

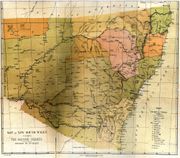

For the next 40 years the history of New South Wales was identical with the History of Australia

, since it was not until 1803 that any settlements were made outside the current boundaries of New South Wales, and these, at Hobart

and Launceston

in Van Diemen's Land

(Tasmania), were at first dependencies of New South Wales. It was not until 1825 that Van Diemen's Land became a separate colony. Also that year, on 16 July, the border of New South Wales was set further west at the Western Australia

border (129th meridian

) to encompass the short lived settlement on Melville Island. In 1829 this border became the border with Western Australia

, which was proclaimed a colony.

The indigenous Australians

or Aboriginal people had lived in what is now New South Wales for at least 50,000 years, making their living through hunting, gathering and fishing. The impact of European settlement on these people was immediate and devastating. They had no natural resistance to European diseases, and epidemics of measles

and smallpox

spread far ahead of the frontier of settlement, radically reducing population and fatally disrupting indigenous society. Although there was some resistance to European occupation, in general the indigenous people were evicted from their lands without difficulty. Dispossession, disease, violence and alcohol reduced them to a remnant within a generation in most areas.

Accounts of early encounters between Sydney's Aboriginal people and the British are provided by the author Watkin Tench

, who was an officer on the First Fleet

and the writer of one of the first works of literature about New South Wales. The colony struggled in its early days for economic self-sufficiency, since supplies from Britain were few and inadequate. The whaling

industry provided some early revenue, but it was the development of the wool

industry by John MacArthur

and his wife Elizabeth Macarthur

and other enterprising settlers that created the colony's first major export industry. For the first half of the 19th century New South Wales was essentially a sheep run, supported by the port of Sydney and a few subsidiary towns such as Newcastle

(where a permanent settlement was established in 1804) and Bathurst

(1815). Newcastle, north of Sydney, was named after the English coal mining city and would grow to be a major industrial centre and the State's second largest city, but it was initially established as a severe punishment camp for troublesome convicts following the Castle Hill Rebellion. The State's third city, Wollongong, south of Sydney, began in 1829 as an outpost for a contingent of soldiers sent in response to conflict between local Aborigines and the unruly timber-getters who had established themselves in the area. Agriculture soon established itself and dairy and coal mining had begun by the 1840s and the city also grew to become a major industrial centre.

Constitutionally, New South Wales was founded as an autocracy run by the Governor, although he nearly always exercised his powers within the restraints of British law. In practice the early Governors ruled by consent, with the advice of military officers, officials and leading settlers. The New South Wales Corps

was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment to relieve the marines who had accompanied the First Fleet

. Officers of the Corps soon became involved in the corrupt and lucrative rum trade in the colony. In the Rum Rebellion

of 1808, the Corps, working closely with the newly established wool trader John Macarthur

, staged the only successful armed takeover of government in Australian history, deposing Governor

William Bligh

and instigating a brief period of military rule in the colony prior to the arrival from Britain of Governor Lachlan Macquarie

in 1810.

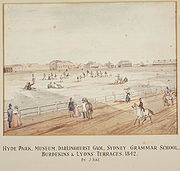

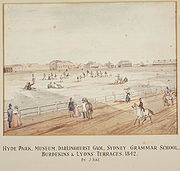

Macquarie served as the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales, from 1810 to 1821 and had a leading role in the social and economic development of New South Wales which saw it transition from a penal colony

to a budding free society. He established public works, a bank

, churches, and charitable institutions and sought good relations with the Aborigines. In 1813 he sent Blaxland

, Wentworth

and Lawson across the Blue Mountains, where they found the great plains of the interior. Central, however to Macquarie's policy was his treatment of the emancipist

s, whom he decreed should be treated as social equals to free-settlers in the colony. Against opposition, he appointed emancipists to key government positions including Francis Greenway

as colonial architect and William Redfern

as a magistrate. London judged his public works to be too expensive and society was scandalised by his treatment of emancipists. His legacy lives on with Macquarie Street, Sydney

bearing his name as the well as the New South Wales Parliament and various buildings designed during his tenure including the UNESCO

listed Hyde Park Barracks

.

In 1821 there were still only 36,000 Europeans in the country. Although the number of free settlers began to increase rapidly after the end of the Napoleonic Wars

in 1815, convicts were still 40% of the population in 1820, and it was not until the 1820s that free settlers began to occupy most of what is now rural New South Wales. An inland settlement was established at Bathurst

, west of the Blue Mountains, on the banks of the Macquarie River. It was proclaimed a town in 1815 and properties across the plains began to support cattle and grow wheat, vegetables and fruit and produce fine wool for export to the knitting mills of industrial Britain. The period from 1820 to 1850 is regarded as the golden age of the squatters

.

In 1825 the New South Wales Legislative Council

, Australia's oldest legislative body, was established, as an appointed body to advise the Governor. In the same year trial by jury

was introduced, ending the military's judicial power. In 1842 the Council was made partly elective, through the agitation of democrats like William Wentworth

. This development was made possible by the abolition of transportation of convicts to New South Wales in 1840, by which time 150,000 convicts had been sent to Australia. After 1840 the settlers saw themselves as a free people and demanded the same rights they would have had in Britain.

In October 1795 George Bass

In October 1795 George Bass

and Matthew Flinders

, accompanied by William Martin sailed the boat Tom Thumb out of Port Jackson

to Botany Bay

and explored the Georges River

further upstream than had been done previously by the colonists. Their reports on their return led to the settlement of Banks' Town

. In March 1796 the same party embarked on a second voyage in a similar small boat, which they also called the Tom Thumb. During this trip they travelled as far down the coast as Lake Illawarra

, which they called Tom Thumb Lagoon. They discovered and explored Port Hacking

. In 1798-99, Bass and Flinders set out in a sloop and circumnavigated Tasmania

, thus proving it to be an island.

Aboriginal guides and assistance in the European exploration of the colony were common and often vital to the success of missions. In 1801-02 Matthew Flinders in The Investigator lead the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree

, of the Sydney district, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Bennelong

and a companion had become the first people born in the area of New South Wales to sail for Europe, when, in 1792 they accompanied Governor Phillip to England and were presented to King George III.

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland

, William Lawson and William Wentworth

succeeded in crossing the formidable barrier of forested gulleys and shere cliffs presented by the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, by following the ridges instead of looking for a route through the valleys. At Mount Blaxland they looked out over "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years", and expansion of the British settlement into the interior could begin.

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane

, commissioned Hamilton Hume

and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell

to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales's western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824-25, Hume and Hovell

journeyed to Port Phillip and back. They made many important discoveries including the Murray River

(which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales

and Corio Bay, Victoria.

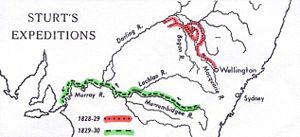

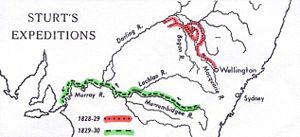

Charles Sturt

led an expedition along the Macquarie River in 1828 and discovered the Darling River

. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River

into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party then followed this river to its junction with the Darling River

, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued down river on to Lake Alexandrina

, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia

. Suffering greatly, the party had to then row back upstream hundreds of kilometers for the return journey.

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps

in 1839 and became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko

in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko

.

A golden age of a new kind began in 1851 with the announcement of the discovery of payable gold

A golden age of a new kind began in 1851 with the announcement of the discovery of payable gold

near Bathurst

by Edward Hargraves

. In that year New South Wales had about 200,000 people, a third of them within a day's ride of Sydney, the rest scattered along the coast and through the pastoral districts, from the Port Phillip District

in the south to Moreton Bay

in the north. In 1836 a new colony of South Australia

had been established, and its territory separated from New South Wales. The gold rushes of the 1850s brought a huge influx of settlers, although initially the majority of them went to the richest gold fields at Ballarat

and Bendigo

, in the Port Phillip District, which in 1851 was separated to become the colony of Victoria

.

Victoria soon had a larger population than New South Wales, and its upstart capital, Melbourne

, outgrew Sydney. But the New South Wales gold fields also attracted a flood of prospectors, and by 1857 the colony had more than 300,000 people. Inland towns like Bathurst, Goulburn

, Orange

and Young

flourished. Gold brought great wealth but also new social tensions. Multiethnic migrants came to New South Wales in large numbers for the first time. Young became the site of an infamous anti-Chinese miner riot in 1861 and the official Riot Act

was read to the miners on the 14th July – the only official reading in the history of New South Wales. Despite some tension, the influx of migrants also brought fresh ideas from Europe and North America to New South Wales – Norwegians introduced Skiing in Australia

to the hills above the Snowy Mountains

gold rush town of Kiandra around 1861. A famous Australian son was also born to a Norwegian miner in 1867, when the bush ballad

eer Henry Lawson

was born at the Grenfell goldfields

.

In 1858, a new gold rush began in the far north, which led in 1859 to the separation of Queensland

as a new colony. New South Wales thus attained its present borders, although what is now the Northern Territory

remained part of the colony until 1863, when it was handed over to South Australia.

The separation and rapid growth of Victoria and Queensland mark the real beginning of New South Wales as a political and economic entity distinct from the other Australian colonies. Rivalry between New South Wales and Victoria was intense throughout the second half of the 19th century, and the two colonies developed in radically different directions. Once the easy gold ran out by about 1860, Victoria absorbed the surplus labour

force from the gold fields in manufacturing, protected by high tariff

walls. Victoria became the Australian stronghold of protectionism

, liberalism

and radicalism

. New South Wales, which was less radically affected demographically by the gold rushes, remained more conservative, still dominated politically by the squatter class and its allies in the Sydney business community. New South Wales, as a trading and exporting colony, remained wedded to free trade

.

At Broken Hill, New South Wales

in the 1880s, BHP Billiton

(now a major global mining and gas company) began as a silver, lead and zinc mine operation. By 1891, the population of the Outback town had passed 21,000, making Broken Hill the third largest town in the colony of New South Wales.

In the course of the 19th century the increasingly ambitious colony established many of its major cultural institutions. The first Sydney Royal Easter Show

In the course of the 19th century the increasingly ambitious colony established many of its major cultural institutions. The first Sydney Royal Easter Show

, an agricultural exhibition and New South Wales cultural institution, began in 1823. Alexander Macleay

started collecting the exhibits of Australia's oldest museum - Sydney's Australian Museum

– in 1826 and the current building opened to the public in 1857. The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper began printing in 1831. The University of Sydney

commenced in 1850. The Royal National Park

, south of Sydney opened in 1879 (second only to Yellowstone National Park

in the USA). An academy of art formed in 1870 and the present Art Gallery of New South Wales

building began construction in 1896.

The New South Wales Rugby Union

(or then, The Southern RU – SRU) was established in 1874, and the very first club competition took place in Sydney that year. In 1882 the first New South Wales team

was selected to play Queensland

in a two-match series (initially popular, the sport would became secondary in popularity in New South Wales after the creation of the New South Wales Rugby League

as a professional code in 1907). In 1878 the inaugural first class cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground

was played between New South Wales and Victoria.

The Sydney International Exhibition of 1879 showcased the colonial capital to the world. Some exhibits from this event were kept to constitute the original collection of the new Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum of New South Wales (today's Powerhouse Museum

).

Two Sydney journalists, J.F. Archibald and John Haynes

, founded The Bulletin

magazine: the first edition appeared on 31 January 1880. It was intended to be a journal of political and business commentary, with some literary content. Initially radical, nationalist, democratic and racist, it gained wide influence and became a celebrated entry-point to publication for Australian writers and cartoonists such as Henry Lawson

, Banjo Paterson

, Miles Franklin

, and the illustrator and novelist Norman Lindsay

. A celebrated literary debate

played out on the pages of the Bulletin about the nature of life in the Australian bush featuring the conflicting views of such as Paterson (called romantic) and Lawson (who saw bush life as exceedingly harsh) and notions of an Australian 'national character' were taking firmer root.

William Wentworth

William Wentworth

established the Australian Patriotic Association (Australia's first political party) in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales. The reformist attorney general, John Plunkett

, sought to apply Enlightenment

principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, first by extending jury rights to emancipist

s, then by extendeding legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and Aborigines

. Plunkett twice charged the colonist perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre

of Aborigines with murder, resulting in a conviction and his landmark Church Act of 1836 disestablished

the Church of England

and established legal equality between Anglicans

, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.

In 1838, the celebrated humanitarian Caroline Chisolm arrived at Sydney and soon after began her work to alleviate the conditions for the poor women migrants of the colony. She met every immigrant ship at the docks, found positions for immigrant girls and established a Female Immigrants' Home. Later she began campaiging for legal reform to alleviate poverty and assist female immigration and family support in the colonies.

In 1838, the celebrated humanitarian Caroline Chisolm arrived at Sydney and soon after began her work to alleviate the conditions for the poor women migrants of the colony. She met every immigrant ship at the docks, found positions for immigrant girls and established a Female Immigrants' Home. Later she began campaiging for legal reform to alleviate poverty and assist female immigration and family support in the colonies.

In 1840, the Sydney City Council was established. Men who possessed 1000 pounds worth of property were able to stand for election and wealthy landowners were permitted up to four votes each in elections. Australia's first parliamentary elections were conducted for the New South Wales Legislative Council

in 1843, again with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership or financial capacity. The Australian Colonies Government Act [1850] was a landmark development which granted representative constitutions to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania and the colonies enthusiastically set about writing constitutions which produced democratically progressive parliaments – though the constitutions generally maintained the role of the colonial upper houses as representative of social and economic "interests" and all established Constitutional Monarchies

with the British monarch as the symbolic head of state.

The end of transportation and the rapid growth of population following the gold rush led to a demand for "British institutions" in New South Wales, which meant an elected parliament and responsible government

. In 1851 the franchise for the Legislative Council was expanded, but this did not satisfy the settlers, many of whom (such as the young Henry Parkes

) had been Chartists

in Britain in the 1840s. Successive Governors warned the Colonial Office of the dangers of republicanism

if the demands for self-government were not met. There was, however, a prolonged battle between the conservatives, now led by Wentworth, and the democrats as to what kind of constitution New South Wales would have. The key issue was control of the pastoral lands, which the democrats wanted to take away from the squatters and break up into farms for settlers. Wentworth wanted a hereditary upper house controlled by the squatters to prevent any such possibility. The radicals, led by rising politicians like Parkes and journalists like Daniel Deniehy

, ridiculed suggestions of a "bunyip

aristocracy."

1855 saw the granting of the right to vote to all male British subjects 21 years or over in South Australia

. This right was extended to Victoria in 1857 and New South Wales the following year (the other colonies followed until, in 1896, Tasmania became the last colony to grant universal male suffrage).

The New South Wales Constitution Act of 1855, steered through the British Parliament

by the veteran radical Lord John Russell

, who wanted a constitution which balanced democratic elements against the interests of property, as did the Parliamantary system in Britain at this time. The Act created a bicameral

Parliament of New South Wales

, with a lower house, the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

, consisting of 54 members elected by adult males who met a moderate property qualification (anyone who owned property worth a hundred pounds, or earned a hundred pounds a year, or held a pastoral licence, or who paid ten pounds a year for lodgings, could vote). The Assembly was heavily malapportioned in favour of the rural areas. The Legislative Council was to consist of at least 21 members (but with no upper limit) appointed for life by the Governor, and Council members had to meet a higher property qualification.

These seemed like formidable barriers to democracy, but in practice they did not prove so, because the Constitution Act could be modified by simple majorities of both Houses. In 1858 the property franchise for the Assembly was abolished, and the secret ballot

introduced. Since the principle that the Governor should always act on the advice of his ministers was soon established, a Premier whose bills were rejected by the Council could simply advise the Governor to appoint more members until the opposition was "flooded": usually the threat of "flooding" was enough. The ministry of Charles Cowper

marked the victory of colonial liberalism, although New South Wales liberals were never as radical as those in Victoria or South Australia. The major battle for the liberals, unlocking the lands from the squatters, was more or less won by John Robertson, five times Premier during the 1860s, who passed the Robertson Land Acts

to break up the squatters' estates.

From the 1860s onwards government in New South Wales became increasingly stable and assured. Fears of class conflict faded as the population bulge resulting from the gold rushes was accommodated on the newly available farmlands and in the rapidly growing towns. The last British troops left the colony in 1870, and law and order was maintained by the police and a locally raised militia, which had little to do apart from catching a few bushranger

From the 1860s onwards government in New South Wales became increasingly stable and assured. Fears of class conflict faded as the population bulge resulting from the gold rushes was accommodated on the newly available farmlands and in the rapidly growing towns. The last British troops left the colony in 1870, and law and order was maintained by the police and a locally raised militia, which had little to do apart from catching a few bushranger

s. The only issue which really excited political passions in this period was education, which was the source of bitter conflict between Catholics

, Protestants

, and secularists

, who all had conflicting views on how schools should be operated, funded and supervised. This was a major preoccupation for Henry Parkes, the dominant politician of the period (he was Premier five times between 1872 and 1889). In 1866 Parkes, as Education Minister, brought in a compromise Schools Act that brought all religious schools under the supervision of public boards, in exchange for state subsidies. But in 1880 the secularists won out when Parkes withdrew all state aid for church schools and established a statewide system of free secular schools.

New South Wales and Victoria continued to develop along divergent paths. Parkes and his successor as leader of the New South Wales liberals, George Reid

, were Gladstonian liberals

committed to free trade, which they saw as both economically beneficial and as necessary for the unity of the British Empire

. They regarded Victorian protectionism as economically foolish and narrowly parochial. It was this hostility between the two largest colonies, symbolised by Victorian customs posts along the Murray River

, which prevented any moves towards uniting the Australian colonies, even after the advent of the railways and the telegraph made travel and communication between the colonies much easier by the 1870s. So long as Victoria was larger and richer than New South Wales, the mother colony (as it liked to see itself) would never agree to surrender its free trade principles to a national or federal government which would be dominated by Victorians.

into the south-west Pacific area made colonial defence an urgent question, which became more urgent with the rise of Japan

as an expansionist power. Finally the issue of Chinese and other non-European immigration made federation of the colonies an important issue, with advocates of a White Australia policy

arguing the necessity of a national immigration policy.

As a result the movement for federation was initiated by Parkes with his Tenterfield Oration

of 1889 (earning him the title "Father of Federation"), and carried forward after Parkes' death by another New South Wales politician, Edmund Barton

. Opinion in New South Wales about federation remained divided through the 1890s. The northern and southern border regions, which were most inconvenienced by the colonial borders and the system of intercolonial tariffs, were strongly in favour, while many in the Sydney commercial community were sceptical, fearing that a national Parliament would impose a national tariff (which was indeed what happened). The first attempt at federation in 1891 failed, mainly as a result of the economic crisis of the early '90s. It was the federalists of the border regions who revived the federal movement in the later '90s, leading up to the Constitutional Convention

of 1897-98 which adopted a draft Australian Constitution.

When the draft was put to referendum

in New South Wales in 1899, Reid (Free Trade Premier from 1894 to 1899), adopted an equivocal position, earning him the nickname "Yes-No Reid." The draft was rejected, mainly because New South Wales voters thought it gave the proposed Senate

, which would dominated by the smaller states, too much power. Reid was able to bargain with the other Premiers to modify the draft so that it suited New South Wales interests, and the draft was then approved. On 1 January 1901, following a proclamation

by Queen Victoria

, New South Wales ceased to be a self-governing colony and became a state of the Commonwealth of Australia. Although the new Governor-General

and Prime Minister

were sworn in Sydney, Melbourne was to be the temporary seat of government until the permanent seat of government was established. This was to be in New South Wales, but at least 100 miles (160 km) from Sydney. The first Prime Minister (Barton) the first Opposition Leader (Reid) and the first Labor

leader (Chris Watson

) were all from New South Wales.

At the time of federation the New South Wales economy was still heavily based on agriculture, particularly wool growing, although mining - coal from the Hunter Valley

At the time of federation the New South Wales economy was still heavily based on agriculture, particularly wool growing, although mining - coal from the Hunter Valley

and silver, lead and zinc from Broken Hill

- was also important. Federation was followed by the imposition of protective tariffs just as the Sydney Free Traders had feared, and this boosted domestic manufacturing. Farmers, however, suffered from increased costs, as well as from the prolonged drought that afflicted the state at the turn of the century. A further boost to both manufacturing and farming came from the increased demand during World War I

. By the 1920s New South Wales was overtaking Victoria as the centre of Australian heavy industry, symbolised by the Broken Hill Proprietary

(BHP) steelworks at Newcastle, opened in 1915, and another steel mill at Port Kembla

in 1928.

The growth of manufacturing and mining brought with it the growth of an industrial working class. Trade union

s had been formed in New South Wales as early as the 1850s, but it was great labour struggles of the 1890s that led them to move into politics. The most important was the Australian Workers' Union

(AWU), formed from earlier unions by William Spence

and others in 1894. The defeat of the great shearers' and maritime strikes in the 1890s led the AWU to reject direct action and to take the lead in forming the Labor Party

. Labor had its first great success in 1891, when it won 35 seats in the Legislative Assembly, mainly in the pastoral and mining areas. This first parliamentary Labor Party, led by Joseph Cook

, supported Reid's Free Trade government, but broke up over the issue of free trade versus protection, and also over the "pledge" which the unions required Labor members to take always to vote in accordance with majority decisions. After federation, Labor, led by James McGowen

, soon recovered, and won its first majority in the Assembly in 1910, when McGowen became the state's first Labor Premier.

This early experience of government, plus the social base of New South Wales party in the rural areas rather than in the militant industrial working class of the cities, made New South Wales Labor notably more moderate than its counterparts in other states, and this in turn made it more successful at winning elections. The growth of the coal, iron, steel and shipbuilding industries gave Labor new "safe" areas in Newcastle and Wollongong

, while the mining towns of Broken Hill and the Hunter also became Labor strongholds. As a result of these factors, Labor has ruled New South Wales for 59 of the 96 years since 1910, and every leader of the New South Wales Labor Party except one has become Premier of the state.

But Labor came to grief in New South Wales as elsewhere during World War I

, when the Premier, William Holman

, supported the Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes

in his drive to introduce conscription

. New South Wales voters rejected both attempts by Hughes to pass a referendum

authorising conscription, and in 1916 Hughes, Holman, Watson, McGowen, Spence and many other founders of the party were expelled, forming the Nationalist Party

under Hughes and Holman. Federal Labor did not recover from this split for many years, but New South Wales Labor was back in power by 1920, although this government lasted only 18 months, and again from 1925 under Jack Lang

.

In the years after World War I it was the farmers rather than the workers who were the most discontented and militant class in New South Wales. The high prices enjoyed during the war fell with the resumption of international trade, and farmers became increasingly discontented with the fixed prices paid by the compulsory marketing authorities set up as a wartime measure by the Hughes government. In 1919 the farmers formed the Country Party

, led at national level by Earle Page

, a doctor from Grafton

, and at state level by Michael Bruxner

, a small farmer from Tenterfield

. The Country Party used its reliable voting base to make demands on successive non-Labor governments, mainly to extract subsidies and other benefits for farmers, as well as public works in rural areas.

The Great Depression

which began in 1929 ushered a period of unprecedented political and class conflict in New South Wales. The mass unemployment and collapse of commodity prices brought ruin to both city workers and to farmers. The beneficiary of the resultant discontent was not the Communist Party

, which remained small and weak, but Jack Lang's Labor populism. Lang's second government was elected in November 1930 on a policy of repudiating New South Wales' debt to British bondholders and using the money instead to help the unemployed through public works. This was denounced as illegal by conservatives, and also by James Scullin

's federal Labor government. The result was that Lang's supporters in the federal Caucus brought down Scullin's government, causing a second bitter split in the Labor Party. in May 1932 the Governor, Sir Philip Game

, convinced that Lang was acting illegally, dismissed his government, and Labor spent the rest of the 1930s in opposition.

In a Sheffield Shield cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground

in 1930, Don Bradman, a young New South Welshman of just 21 years of age wrote his name into the record books at by smashing the previous highest batting score in first-class cricket with 452 runs not out in just 415 minutes. Although Bradman would later transfer to play for South Australia, his world beating performances provided much needed joy to Australians through the emerging Great Depression

.

The 1938 British Empire Games

were held in Sydney from February 5–12, timed to coincide with Sydney's sesqui-centenary (150 years since the foundation of British settlement in Australia).

By the outbreak of World War II

By the outbreak of World War II

in 1939, the differences between New South Wales and the other states that had emerged in the 19th century had faded as a result of federation and economic development behind a wall of protective tariffs. New South Wales continued to outstrip Victoria as the centre of industry, and increasingly of finance and trade as well.

The radicalism of the Lang period subsided as the Depression eased, and his removal as Labor Leader in 1939 marked the permanent (as it turned out) defeat of the left of the New South Wales Labor Party. Labor returned to office under the moderate leadership of William McKell

in 1941 and stayed in power for 24 years.

World War II saw another surge in industrial development to meet the needs of a war economy, and also the elimination of unemployment. When Ben Chifley

, a railwayman from Bathurst, became Prime Minister in 1945, New South Wales Labor assumed what it saw as its rightful position of national leadership.

After launching their Pacific War

, the Imperial Japanese Navy

managed to infiltrate New South Wales waters

and in late May and early June 1942, Japanese submarines made a series of attacks

on the cities of Sydney and Newcastle. Though casualties were light, the population feared Japanese invasion. The main Japanese naval advance towards Australian territory was however halted with the assistance of the United States Navy

, in May 1942, at the Battle of the Coral Sea

. The Cowra Breakout

of 1944 saw Japanese prisoners of war launch a suicidal escape attempt from their camp in the Central West of New South Wales. This is considered the only fighting within New South Wales of the war.

The postwar years, however, saw renewed industrial conflict, culminating in the 1949 coal strike

The postwar years, however, saw renewed industrial conflict, culminating in the 1949 coal strike

, largely fomented by the Communist Party of Australia

, which crippled the state's industry. This contributed to the defeat of the Chifley government

at the 1949 election

s and the beginning of the long rule at a Federal level of Robert Menzies

, a politician from Victoria, of the newly founded Liberal Party of Australia

. The postwar years also saw massive immigration to Australia, begun by Chifley's Immigration Minister, Arthur Calwell

, and continued under the Liberals. Sydney, hitherto an almost entirely British and Irish city by origin (apart from a small Chinese community), became increasingly multi-cultural, with many immigrants from Italy

, Greece

, Malta

and eastern Europe (including many Jews

), and later from Lebanon

and Vietnam

, permanently changing its character.

The Snowy Mountains Scheme

began construction in the state's south. This hydroelectricity

and irrigation

complex in the Snowy Mountains

called for the construction of sixteen major dams and seven power stations between 1949 and 1974. It remains the largest engineering project undertaken in Australia and necessitated the employment of 100,000 people from over 30 countries

. Socially this project symbolises a period during which Australia became an ethnic "melting pot" of the twentieth century but which also changed Australia's character and increased its appreciation for a wide range of cultural diversity. The Scheme built several temporary towns for its construction workers, several of which have become permanent: notably Cabramurra

, which became highest town in Australia. The sleepy rural town of Cooma

became a bustling construction economy, while small rural townships like Adaminaby and Jindabyne had to make way for the construction of Lakes Eucumbene

and Jindabyne

. Improved vehicular access to the High Country enabled ski-resort villages to be constructed at Thredbo and Guthega in the 1950s by ex-Snowy Scheme workers who realised the potential for expansion of Skiing in Australia

.

Labor stayed in power in New South Wales until 1965, growing increasingly conservative and (according to its critics) lazy and even corrupt in office. In 1965 a vigorous Liberal leader, Robert Askin

, finally broke Labor's long grip on power, and stayed in office for ten years. During these years Sydney began its transformation into a world city and a centre of the arts, with the building of the Sydney Opera House

as the great symbol of the period. The rest of the state, however, began a gradual decline, demographically and economically, as Australia lost some of its traditional export markets for primary products in Britain and as New South Wales' iron, steel and shipbuilding industries became increasingly uncompetitive in the face of competition from Japan

and other new entrants. Sydney's share of the state's population and wealth grew steadily. One consequence of this was a strong secessionist movement in the New England

region of northern New South Wales, which for a time looked as though it might succeed in forming a new state, but which faded away in the late 1960s.

Since the 1970s New South Wales has undergone an increasingly rapid economic and social transformation. Old industries such as steel and shipbuilding have largely disappeared, and although agriculture remains important, its share of the state's income is smaller than ever before. New industries such as information technology, education, financial services and the arts, largely centred in Sydney, have risen to take their place. Coal exports to China are increasingly important to the state's economy. Tourism has also become hugely important, with Sydney as its centre but also stimulating growth on the North Coast, around Coffs Harbour

Since the 1970s New South Wales has undergone an increasingly rapid economic and social transformation. Old industries such as steel and shipbuilding have largely disappeared, and although agriculture remains important, its share of the state's income is smaller than ever before. New industries such as information technology, education, financial services and the arts, largely centred in Sydney, have risen to take their place. Coal exports to China are increasingly important to the state's economy. Tourism has also become hugely important, with Sydney as its centre but also stimulating growth on the North Coast, around Coffs Harbour

and Byron Bay

. As aviation has replaced shipping, most new migrants to Australia have arrived in Sydney by air rather than in Melbourne by ship, and Sydney now gets the lion's share of new arrivals, mostly from Asia, Latin America and the Middle East.

.jpg) Although generally of mild climate, the State endured several notable natural disasters around the turn of the century. In 1989, an earthquake struck Newcastle. It was a Richter magnitude

Although generally of mild climate, the State endured several notable natural disasters around the turn of the century. In 1989, an earthquake struck Newcastle. It was a Richter magnitude

5.6 earthquake

and one of Australia's most serious natural disaster

s, killing 13 people and injuring more than 160. The damage bill has been estimated at A$

4 billion (including an insured loss of about $1 billion). The Newcastle earthquake was the first Australian earthquake in recorded history to claim human lives. The following, year, 1990, saw major flooding in the State's central west, with Nyngan suffering a devasting innundation. In 1993-4, the State suffered a serious bushfire season

, causing destruction even within urban areas of Sydney. Agricultural production was severely curtailed by prolonged drought

during the late 1990s and early 2000s, particularly in the Murray-Darling basin

. The drought was followed by sever flooding in 2010.

In 1973, after a long period of planning and construction, the Sydney Opera House

was officially opened. The building was from a design by Joern Utzon. It became a symbol not only of Sydney, but of the Australian nation and was inscribed by UNESCO

in 2007. Sydney has maintained extensive political, economic and cultural influence over Australia as well as international renown in recent decades. The city hosted the 2000 Olympic Games

, the 2003 Rugby World Cup

and the APEC Leaders conference of 2007

. From 1991-2007, Sydney-siders governed as Prime Minister of Australia

- first Paul Keating

(1991-1996) and later John Howard

(1996-2007).

In recent decades Sydney has also undergone a major social liberalisation, with huge entertainment and gambling industries. Though there has been a decline in the dominance of Christianity

through increased secularisation and the growing presence of an increasingly diverse migrant population, Sydney's two outspoken Archbishops, George Pell

(Catholic) and Peter Jensen (Anglican

) remain vocal in national debates and the hosting of Catholic World Youth Day 2008

, led by Pope Benedict XVI

, drew huge crowds of worshipers to the city. An evangelical Christian "bible belt" has developed in the north-western suburbs. Buddhist and Muslim

communities in particular are growing, but so is irreligiosity. While a grant from the State government permitted the final completion of the spires of St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney

in 2000 (the foundation stone was laid in 1868), construction of the present structure of the large Auburn Gallipoli Mosque

began in 1986 and at Wollongong, south of Sydney, Nan Tien Temple

opened in 1995 as one of the southern hemisphere

's largest Buddhist temples. Sydney has gained a reputation for secularism and hedonism, with the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras

becoming a world-famous event. Star City Casino

opened in the mid 1990s as Sydney's only legal casino.

The Australian Labor Party

has had long periods of governance in New South Wales in recent decades, holding power under Neville Wran

and Barrie Unsworth

from 1976 to 1988. A period of Liberal-National Coalition

rule followed under Nick Greiner

and John Fahey

from 1988 to 1995, but the Labor Party was led back to power by Bob Carr

in 1995 and has remained in office ever since. Carr retired and was succeeded by a series of Labor premiers between 2005-2011: Morris Iemma

won the 2007 Election but his party replaced him with Nathan Rees

in 2007, who was, in turn, replaced by Kristina Keneally

in 2008. Two recent Premiers have been of non-British background: Greiner (Liberal 1988-92), who is of Hungarian descent, and Iemma whose parents are Italian. The current Governor of New South Wales, Marie Bashir

, is of Lebanese origin and is the first woman to be appointed to the office of Governor. The current Premier of New South Wales, Kristina Keneally

, was born and raised in the United States and became the first female Premier when her party selected her as leader in 2008. Elections to the 55th Parliament of New South Wales

are fixed to be held on Saturday, 26 March 2011.

Most commentators predict that Sydney and the coast areas of northern New South Wales will continue to grow in the coming decades, although Bob Carr and others have argued that Sydney (which by 2006 had over 4 million people) cannot grow any bigger without putting intolerable strain on its environment and infrastructure. The southern coastal areas around Canberra are also expected to grow, although less rapidly. The rest of the state, however, is expected to continue to decline, as traditional industries disappear. Already many small towns in western New South Wales have lost so many services and businesses that they are no longer viable, causing population to consolidate in regional centres like Dubbo and Wagga Wagga.

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n State of New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

and its preceding Indigenous and British colonial societies. The Mungo Lake remains indicate occupation of New South Wales by Aboriginal Australians for at least 40,000 years. The English navigator James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

became the first European to map the coast in 1770 and a First Fleet

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

of British convicts followed to establish a penal colony

Penal colony

A penal colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general populace by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory...

at Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

in 1788. The colony established an autonomous Parliamentary democracy from the 1840s and became a state

States and territories of Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia is a union of six states and various territories. The Australian mainland is made up of five states and three territories, with the sixth state of Tasmania being made up of islands. In addition there are six island territories, known as external territories, and a...

of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 following a vote to Federate with the other British colonies of Australia. Through the 20th century, the state was a major destination for an increasingly diverse collection of migrants from many nations. In the 21st century, the state is the most populous in Australia, and its capital, Sydney is a major financial capital and host to international cultural and economic events.

Ancient history

The first people to occupy the area now known as New South Wales were Australian Aborigines

Australian Aborigines

Australian Aborigines , also called Aboriginal Australians, from the latin ab originem , are people who are indigenous to most of the Australian continentthat is, to mainland Australia and the island of Tasmania...

. Their presence in Australia began around 40,000–60,000 years ago with the arrival of the first of their ancestors by boat from what is now Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

. Their descendants moved south and, though never large in numbers, occupied all areas of Australia, including the future New South Wales.

Mungo Man and other remains have been found at the dried up Lake Mungo

Lake Mungo

Lake Mungo is a dry lake in south-western New South Wales, Australia. It is located about 760 km due west of Sydney and 90 km north-east of Mildura. The lake is the central feature of Mungo National Park, and is one of seventeen lakes in the World Heritage listed Willandra Lakes Region...

in New South Wales, some 3000 km south of the North Coast of Australia, and have been dated to approximately 40,000 years ago. These early humans appear to have been buried with ceremonial accompaniment and have been found close to stone tools and the bones of now extinct mega fauna (such as giant kangaroos and wombats). These are the earliest human remains yet found in Australia, though precise dating is difficult and debated. They nevertheless appear to confirm that New South Wales was populated some tens of thousands of years before the arrival of the British First Fleet

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

at a time when the climate was far wetter and humans were conducting some of their earliest religious and artistic practices. Examples of Aboriginal stone tools and Aboriginal art (often recording the stories of the Dreamtime

Dreamtime

In the animist framework of Australian Aboriginal mythology, The Dreaming is a sacred era in which ancestral Totemic Spirit Beings formed The Creation.-The Dreaming of the Aboriginal times:...

religion) can be found throughout New South Wales: even within the metropolis of modern Sydney, as in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Ku-ring-gai Chase is a national park in New South Wales, Australia, 25 km north of Sydney located largely within the Ku-ring-gai, Hornsby, Warringah and Pittwater municipal areas. Ku-ring-gai Chase is also officially classed as a suburb by the Geographical Names Board of New South Wales...

.

1770 James Cook's proclamation

In 1770 Lieutenant (later Captain) James CookJames Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

, in command of the HMS Endeavour

HMS Endeavour

HMS Endeavour may refer to one of the following ships:In the Royal Navy:, a 36-gun ship purchased in 1652 and sold in 1656, a 4-gun bomb vessel purchased in 1694 and sold in 1696, a fire ship purchased in 1694 and sold in 1696, a storeship hoy purchased in 1694 and sold in 1705, a storeship...

, sailed along the east coast of Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, becoming the first known Europeans to do so. On 19 April 1770, the crew of the Endeavour sighted the east coast of Australia and ten days later landed at a bay in what is now southern Sydney. The ship's naturalist, Sir Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

, was so impressed by the volume of flora and fauna hitherto unknown to European science, that Cook named the inlet Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

. Cook charted the East coast to its northern extent and, on 22 August, at Possession Island in the Torres Strait

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait is a body of water which lies between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is approximately wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost continental extremity of the Australian state of Queensland...

, Cook wrote in his journal: "I now once more hoisted English Coulers [sic] and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

, took possession of the whole Eastern Coast from the above Latitude 38°S

38th parallel south

The 38th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 38 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific Ocean, and the southern end of South America, including the Andes Mountains and Patagonia.At this latitude...

down to this place by the name of New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

." Cook and Banks then reported favourably to London on the possibilities of establishing a British colony at Botany Bay.

Britain thereby became the first European power to officially claim any area on the Australian mainland. "New South Wales", as defined by Cook's proclamation, covered most of eastern Australia, from 38°S 145°E (near the later site of Mordialloc, Victoria

Mordialloc, Victoria

Mordialloc is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 24 km south-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Kingston...

), to the tip of Cape York

Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in northern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth...

, with an unspecified western boundary. By implication, the proclamation excluded: Van Diemen's Land

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

(later Tasmania), which had been claimed for the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

by Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

in 1642; a small part of the mainland south of 38° (later southern Victoria) and; the west coast of the continent

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

(later Western Australia), which Louis de Saint Aloüarn

Louis Aleno de St Aloüarn

Louis Francois Marie Aleno de Saint Aloüarn was a notable French naval officer and explorer.St Aloüarn was the first European to make a formal claim of sovereignty — on behalf of France — over the west coast of Australia, which was known at the time as "New Holland"...

officially claimed for France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

in 1772 — even though it had been mapped previously by Dutch mariners.

1788: Establishment of the colony

Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip RN was a British admiral and colonial administrator. Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales, the first European colony on the Australian continent, and was the founder of the settlement which is now the city of Sydney.-Early life and naval career:Arthur Phillip...

arrived with the First Fleet

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

to found a convict settlement at what is now Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

. Phillip, as Governor of New South Wales, exercised nominal authority over all of Australia east of the 135th meridian east

135th meridian east

The meridian 135° east of Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, Australasia, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole....

between the latitudes of 10°37'S and 43°39'S, which included most of New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

except for the southern part of South Island

South Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

.

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

of 11 vessels consisted of over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts (192 women and 586 men). A few days after arrival at Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson

Port Jackson

Port Jackson, containing Sydney Harbour, is the natural harbour of Sydney, Australia. It is known for its beauty, and in particular, as the location of the Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge...

where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove is a small bay on the southern shore of Port Jackson , on the coast of the state of New South Wales, Australia....

on 26 January 1788. This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day

Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia...

. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and a safe harbour, which Philip famously described as:

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Enlightened for his Age, Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers - most notably Watkin Tench

Watkin Tench

Lieutenant-General Watkin Tench was a British Marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first settlement in Australia in 1788...

– left behind journals and accounts of which tell of immense hardships during the first years of settlement. Often Phillip's officers despaired for the future of New South Wales. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were few and far between. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney – many "professional criminals" with few of the skills required for the establishment of a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick or unfit for work and the conditions of healthy convicts only deteriorated with hard labour and poor sustenance in the settlement. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its 'passengers' through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791 however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils and fixed on the Parramatta region as a promising area for expansion and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life, leaving Sydney Cove as an important port and focus of social life. Poor equipment and unfamiliar soils and climate continued to hamper the expansion of farming from Farm Cove to Parramatta and Toongabbie, but a building programme, assisted by convict labour, advanced steadily. Between 1788–92, convicts and their gaolers made up the majority of the population - but after this, a population of emancipated convicts began to grow who could be granted land and these people pioneered a non-government private sector economy and were later joined by soldiers whose military service had expired - and finally, free settlers who began arriving from Britain. Governor Phillip departed the colony for England on 11 December 1792, with the new settlement having survived near starvation and immense isolation for four years

For the next 40 years the history of New South Wales was identical with the History of Australia

History of Australia

The History of Australia refers to the history of the area and people of Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding Indigenous and colonial societies. Aboriginal Australians are believed to have first arrived on the Australian mainland by boat from the Indonesian archipelago between 40,000 to...

, since it was not until 1803 that any settlements were made outside the current boundaries of New South Wales, and these, at Hobart

Hobart

Hobart is the state capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Founded in 1804 as a penal colony,Hobart is Australia's second oldest capital city after Sydney. In 2009, the city had a greater area population of approximately 212,019. A resident of Hobart is known as...

and Launceston

Launceston, Tasmania

Launceston is a city in the north of the state of Tasmania, Australia at the junction of the North Esk and South Esk rivers where they become the Tamar River. Launceston is the second largest city in Tasmania after the state capital Hobart...

in Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

(Tasmania), were at first dependencies of New South Wales. It was not until 1825 that Van Diemen's Land became a separate colony. Also that year, on 16 July, the border of New South Wales was set further west at the Western Australia

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

border (129th meridian

129th meridian east

The meridian 129° east of Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, Asia, Australia, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole....

) to encompass the short lived settlement on Melville Island. In 1829 this border became the border with Western Australia

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

, which was proclaimed a colony.

The indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. The Aboriginal Indigenous Australians migrated from the Indian continent around 75,000 to 100,000 years ago....

or Aboriginal people had lived in what is now New South Wales for at least 50,000 years, making their living through hunting, gathering and fishing. The impact of European settlement on these people was immediate and devastating. They had no natural resistance to European diseases, and epidemics of measles

Measles

Measles, also known as rubeola or morbilli, is an infection of the respiratory system caused by a virus, specifically a paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus. Morbilliviruses, like other paramyxoviruses, are enveloped, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses...

and smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

spread far ahead of the frontier of settlement, radically reducing population and fatally disrupting indigenous society. Although there was some resistance to European occupation, in general the indigenous people were evicted from their lands without difficulty. Dispossession, disease, violence and alcohol reduced them to a remnant within a generation in most areas.

Accounts of early encounters between Sydney's Aboriginal people and the British are provided by the author Watkin Tench

Watkin Tench

Lieutenant-General Watkin Tench was a British Marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first settlement in Australia in 1788...

, who was an officer on the First Fleet

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

and the writer of one of the first works of literature about New South Wales. The colony struggled in its early days for economic self-sufficiency, since supplies from Britain were few and inadequate. The whaling

Whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales mainly for meat and oil. Its earliest forms date to at least 3000 BC. Various coastal communities have long histories of sustenance whaling and harvesting beached whales...

industry provided some early revenue, but it was the development of the wool

Wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and certain other animals, including cashmere from goats, mohair from goats, qiviut from muskoxen, vicuña, alpaca, camel from animals in the camel family, and angora from rabbits....

industry by John MacArthur

John Macarthur (wool pioneer)

John Macarthur was a British army officer, entrepreneur, politician, architect and pioneer of settlement in Australia. Macarthur is recognised as the pioneer of the wool industry that was to boom in Australia in the early 19th century and become a trademark of the nation...

and his wife Elizabeth Macarthur

Elizabeth Macarthur

Elizabeth Macarthur was born in Devon, England, the daughter of provincial farmers, Richard and Grace Veale, of Cornish origin. Her father died when she was 7; her mother remarried when she was 11, leaving Elizabeth in the care of her grandfather John and friends. Elizabeth married Plymouth...