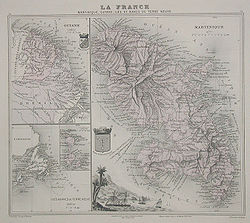

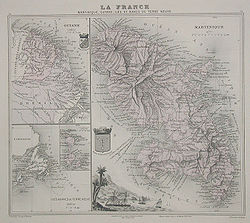

History of Martinique

Encyclopedia

This is a page on the history of the island of Martinique

.

resulted in the decimation of the island's population. Around 400 CE, the Arawaks returned and repopulated the island. Around 600 CE, the Caribs arrived. They exterminated the Arawaks and proceeded to settle on the island over the next few centuries.

charted the island in 1493, making the region known to European interests, but it was not until June 15, 1502, on his fourth voyage, that he actually landed, leaving several pigs and goats on the island. However, the Spaniards ignored the island as other parts of the New World were of greater interest to them.

(Company of the Isles of America, the successor to the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe

). The company contracted with Messrs l'Olive and Duplessis to occupy and govern on its behalf the Caribbean islands belonging to the French crown. This led on September 1, 1635, to Pierre Bélain d'Esnambuc

landing on Martinique with eighty to one hundred French settlers from Saint Cristophe

. They met some resistance that they were able to dispatch quickly because of their far superior weaponry and armor. They settled in the northwestern region that later became known as St. Pierre

at the mouth of the Roxelane River, where they built Fort Saint Pierre.

The following year, d'Esnambuc fell ill and passed the command of the settlement to his nephew, Jacques Dyel du Parquet. At this time the colony's population numbered some 700 men. The settlers cleared the land around St. Pierre to grow crops. They grew manioc and potatoes were grown to live on and rocou, indigo

, tobacco

, and later cacao and cotton

, for export. French and foreign merchants frequently came to the island to buy these exotic products, transforming Martinique into a modestly prosperous colony. The colonists also established another fort, Fort Saint Louis

in 1638. This fort, like Fort Saint Pierre, was little more than a wooden stockade. In 1640, the fort was improved to include a ditch, high stone walls and 26 cannons.

Over the next quarter of a century the French established full control of the island. They systematically killed the fiercely resisting Caribs as they expanded, forcing the survivors back to the Caravelle Peninsula in the Cabesterre (the leeward side of the island).

Although labor-intensive, sugar was a lucrative product to trade, and cultivation on Martinique soon focused only on growing and trading sugar. In 1685, King Louis XIV

Although labor-intensive, sugar was a lucrative product to trade, and cultivation on Martinique soon focused only on growing and trading sugar. In 1685, King Louis XIV

proclaimed "La Traite des Noirs", which authorized the forcible removal of Africans from their homeland and their transport to work as slaves

on the French sugar plantations. Ever since, a strong theme of Martiniquan culture

has been creolization

or interaction between the French colonial settlers, known locally as békés, and the Africans they imported. For over two hundred years, slavery, and slave revolts, would be a major influence on the economy and politics of the island.

The French colonial settlers were peasants attracted by propaganda promising fortune and a life under the sun. The "volunteers" were indentured servants who had to work for their master for three years, after which they were promised their own land. However, the tiring work and hot climate resulted in few of the workers surviving their three years, with the result that constant immigration was necessary for maintaining the workforce. Still, under the directorship of du Parquet, Martinique's economy developed as it exported products to France and the neighboring English and Dutch colonies. In 1645, the Sovereign council was established with several powers, among them the right to grant titles of nobility to families in the islands. In 1648, the Company of the Isles of America started to wind up its affairs and in 1650 du Parquet bought the island.

In 1650 Father Jacques du Tetre built a still for converting the waste from the sugarcane

mills into molasses, which became a major export industry.

In 1654, du Parquet allowed 250 Dutch

Jews

, who were fleeing Brazil

following the Portuguese

conquest, to settle Martinique, where they engaged in the sugar trade. This was by far the most sought after product in Europe and the crop soon became Martinique's biggest export.

After the death of du Parquet, his widow ruled on behalf of his children until 1658, when Louis XIV resumed sovereignty over the island, paying an indemnity of £120,000 to the du Parquet children. At this time, Martinique's population numbered some 5,000 settlers and a few surviving Carib Indians. The Caribs

were eventually exterminated or exiled in 1660.

In 1658, Dominican Fathers

built an estate at Fonds Saint-Jacques. From 1693 to 1705, this was the home of Père Labat, the French Dominican priest who improved the distillery. A colorful character, he was also an explorer, architect, engineer, and historian, and fought as a soldier against the English.

In 1664, Louis transferred the island, this time to the newly-established Compagnie des Indes Occidentales. The next year, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War

, a Dutch fleet under Admiral Michel de Ruyter retired to Martinique to refit after the fleet's indecisive encounter with an English force off Barbados

. Two years later a hurricane devastated Martinique and Guadelope, killing some 2,000 people. This was the first of several natural disasters that would devastate the population of Martinique over the next few centuries.

In 1666 and 1667 the English unsuccessfully attacked. The Treaty of Breda (1667) ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War

and hence the hostilities.

In 1672, Louis XIV ordered the construction of a citadel, Fort Saint Louis

, at Fort Royal Bay to defend Martinique. The next year, the Compagnie des Indes Occidentales decided to establish a town at Fort Royal, even though the location was a malarial swamp. The Compagnie des Indes Occidentales failed in 1674, and the colony reverted to the direct administration of the French crown. Martinique's administration was in the hands of council. The King appointed two members: the Lieutenant-general and the administrator. They chose the other council members (the governor, the Attorney General and the ordinary judge). This organization lasted until 1685.

During the Third Anglo-Dutch War

, de Ruyter returned to Martinique in 1674, this time with the intent to capture Fort Royal. Calm winds and French booms prevented him from sailing his fleet of 30 warships, nine supply ships, and 15 transports into the harbor. The French repulsed his attempt to land his 3,400 troops, causing him to loose 143 men, at a cost of 15 French lives.

In 1675 the first Governor General of the West Indies, Jean-Charles de Baas-Castelmore, arrived in Martinique and served until 1677. His successor was Charles de La Roche-Courbon, comte de Blénac, who served for the first time from 1677 to 1683. He drew up a plan for the city of Fort Royal and improving the fortifications of Fort Saint Louis

. de Blénac was responsible for the 10-year effort that resulted in the building of a 487 meter wall around the peninsula on which the Fort stood, the wall being four meters high and two meters thick, and cutting a ditch that separated from the town. de Blénac served as Governor General again from June 1684 to February 1691, and again from 24 Nov 1691 until his death in 1696.

The growth of the town resulted in the progressive clearing and draining of the mangrove

swamp. By 1681, Fort-Royal was the administrative, military and political capital of Martinique. Still, Saint Pierre, with its better harbor, remained the commercial capital.

In 1685, in France Jean-Baptiste Colbert

promulgated the "Code des Noires" (Code concerning the Blacks), whose 60 articles would regulate slavery in the colonies. The code forbade some cruel acts, but institutionalized others and slavery itself, relegating the status of slaves to that of chattel.

Colbert also ordered the expulsion of the Jews from all the French islands. These Jews then moved to the Dutch island of Curaçao

, where they prospered. In 1692, Charles de La Roche-Courbon, Count of Blénac, the Governor and Lieutenant General of the French colonies in America, named Fort Royal as the capital city of Martinique.

In 1693 the English again unsuccessfully attacked Martinique.

in Paris and transported it to Martinique. He transplanted it on the slopes of Mount Pelee

and was able to harvest his first crop in 1726, or shortly thereafter. By 1736, the number of slaves in Martinique had risen to 60,000 people. In 1750, Saint Pierre had about 15,000 inhabitants, and Fort Royal only about 4,000.

Britain captured the island

during the Seven Years' War

, holding it from 1762 to 1763. Following Britain's victory in the war

there was a strong possibility the island would be annexed by them. However, the sugar trade made the island so valuable to the royal French government that at the Treaty of Paris (1763)

, which ended the Seven Years War, they gave up all of Canada in order to regain Martinique as well as the neighboring island of Guadeloupe

. During the British occupation, Marie Josèph Rose Tascher de la Pagerie, the future Empress Josephine was born to a noble family living on Trois Ilets across the bay from Fort Royal. Also, 1762 saw a yellow fever

epidemic

and in 1763 the French established separate governments for Martinique and Guadeloupe

.

August 2, 1766 saw the birth of Saint-Pierre de Louis Delgrès, a mixed-race free black who would serve in the French army and fight the British in 1794, before becoming the leader of the unsuccessful resistance in Guadeloupe

against General Richepance, whom Napoléon had sent to restore slavery to that colony. On August 13 (in either 1766 or 1767) a hurricane - apparently accompanied by an earthquake - struck the island; 600-1600 were killed. Monsieur de la Pagerie, the father of the future Empress, was almost ruined. At the time, there were some 450 sugar mills in Martinique, and molasses was a major export. Four years later an earthquake shook the island. By 1774, when a decree ended indentured servitude for whites, there were some 18 to 19 million coffee trees on the island. In 1776, one of the most damaging hurricanes in Western history struck the island, killing 6000. Over 100 French and Dutch merchantmen were lost.

In 1779, the future Joséphine de Beauharnais

, first Empress of the French, sailed for France to meet her husband for the first time. In 1782, Admiral de Grasse sailed from Martinique to rendezvous with Spanish forces in order to attack Jamaica

. The subsequent battle of the Saintes

resulted in a massive defeat for the French at the hands of the Royal Navy

.

(1789) also had an impact on Trinidad

when Martiniquan planters and their slaves emigrated there and started to grow sugar and cocoa. In Martinique, there was a small, unsuccessful slave rebellion in Saint Pierre. The French executed six of the ringleaders. On February 4, 1793, Jean Baptiste Dubuc signed an accord in Whitehall

, London, putting Martinique under British jurisdiction until the French Monarchy could be re-established. In doing so he forestalled the spread of the French Revolution

to Martinique by giving the English an excuse to intervene. Notably, the accord guaranteed the continuation of slavery.

In 1794 the French Convention abolished slavery. However, before this decree could get to Martinique and be implemented, the British attacked the island and captured it. A British force under Admiral Sir John Jervis

and Lieutenant General Sir Charles Grey

captured Fort Royal and Fort Saint Louis

on March 22, and Fort Bourbon

two days later. At that point all resistance ceased. On March 30, 1794, the British occupation reinstated the Old Regime, including the Monarchy's Supreme Council and the seneschal

's courts of Trinité, Marin

, and St Pierre

. The Royalists regained possession of their properties and positions, slaves were returned to their masters, and emancipation was forbidden. The government also promulgated an ordinance banning all gatherings of blacks or meetings by slaves, and banned Carnival

. However, the British did require an oath of allegiance to the King of England.

Six years later, in 1800, Jean Kina, an ex-slave from Dominica

and aide-de-camp to a British officer, fled to Morne Lemaître and called on free blacks and slaves to join him in a rebellion in support of the rights of the free blacks. A number did so, leading Kina to occupy his position for over a year. When he marched on Port Royal

though, a British force took over the position and negotiated his surrender in return for amnesty. The British transported Kina to England, where they held him in Newgate Prison

.

In 1802, the British returned the island to the French with the Treaty of Amiens

. When France regained control of Martinique, Napoléon Bonaparte

reinstated slavery. Two years later, he married Martiniquan Josephine de Beauharnais

and crowned her Empress of France.

During the Napoleonic Wars

, in 1804 the British established a fort at Diamond Rock

, outside Fort de France, and garrisoned it with some 120 sailors and five cannons. The Royal Navy

commissioned the fort HMS Diamond Rock and from there were able for 17 months to harass vessels coming into the port. The French eventually sent a fleet of sixteen vessels that retook the island after a fierce bombardment.

The British again captured Martinique in 1809

, and held it until 1814. In 1813, a hurricane killed 3,000 people in Martinique. During Napoleon's 100 Days

in 1815, he abolished the slave trade. At the same time the British briefly re-occupied Martinique. The British, who had abolished the slave trade in their empire in 1807, forced Napoleon's successor, Louis XVIII

to retain the proscription, though it did not become truly effective until 1831.

Martinique has suffered from earthquake

s as well as hurricanes. In 1839, an earthquake believed to have measured 6.5 on the Richter

scale killed some 400 to 700 people, caused severe damage in Saint Pierre, and almost totally destroyed Fort Royal. Fort Royal was rebuilt in wood, reducing the risk from earthquakes, but increasing the risk from fire. That same year, there were 495 sugar producers in Martinique, who produced some 25,900 tons of "white gold".

In February 1848, François Auguste Perrinon

became head of the Committee of Colonists of Martinique. He was a member of the Commission for the abolition of slavery, led by Victor Schoelcher

. On April 27, Schoelcher obtained a decree abolishing slavery in the French Empire. Perrinon was appointed Commissioner General of Martinique, and charged with the task of abolishing slavery there. However, he and the decree did not arrive in Martinique until June 3, by which time Governor Claude Rostoland had already abolished slavery. The imprisonment of a slave at Le Prêcheur

had led to a slave revolt on May 20; two days later Rostoland, under duress, had abolished slavery on the island to quell the revolt. That same year, following the establishment of the Second Republic

, Fort Royal became Fort de France.

In 1851 a law was passed authorizing the creation of two colonial banks with the authority to issue banknotes. This led to the founding of the Bank of Martinique in Saint Pierre, and the Bank of Guadeloupe. (These banks would merge in 1967 to form the present-day Banque des Antilles Française).

Indentured laborers from India started to arrive in Martinique in 1853. Plantation owners recruited the Indians to replace the slaves, who once free, had fled the plantations. This led to the creation of the small but continuing Indian

community in Martinique. This immigration repeated on a smaller scale the importation of Indians to such British colonies as British Guiana

and Trinidad and Tobago

following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833. Towards the end of the century, 1000 Chinese also came as earlier they had come to Cuba

.

The city government in 1857-58 cleared and filled the flood channel encircling Fort de France. The channel had become an open sewer and hence a health hazard. The filled-in channel, La Levee, marked the northern boundary of the city.

Martinique got its second enduring financial institution in 1863 when the Crédit Foncier Colonial opened its doors in Saint Pierre. Its objective was to make long-term loans for the construction or modernization of sugar factories. It replaced the Crédit Colonial, which had been established in 1860, but seems hardly to have gotten going.

In 1868 construction work on the Radoub Basin port facilities at Fort de France finally was completed. The improvements to the port would enable Fort de France better to compete in trade and commerce with Saint Pierre

.

In 1870, rising racial tensions led to the short-lived insurrection in southern Martinique and proclamation in Fort-de-France

of a Martiniquan Republic. The insurrection started with an altercation between a local béké (white) and a black tradesman. A crowd lynched the béke and during the insurrection many sugar factories were torched. The authorities restored order by temporarily imprisoning some 500 rebels in Martinique's forts. Seventy four were tried and found guilty, and the twelve principal leaders were shot to death. The authorities deported the rest to French Guiana

or New Caledonia

.

By this time sugar cane fields covered some 57% of Martinique's arable land. Unfortunately, falling prices for sugar forced many small sugar works to merge. Producers turned to rum production in an attempt to improve their fortunes.

When France established the Third Republic

in 1871, the colonies, Martinique among them, gained representation in the National Assembly.

In 1887, after visiting Panama

, Paul Gauguin

spent some months with his friend Charles Laval

, also a painter, in a cabin some two kilometers south of Saint Pierre. During this period Gauguin produced several paintings featuring Martinique. There is now a small Gauguin museum in Le Carbet

that has reproductions of his Martinique paintings. That same year Harper's Weekly

sent the author and translator Lafcadio Hearn

to Martinique for a short visit; he ended up staying for some two years. After his return to the United States he would publish two books, one an account of his daily life in Martinique and the other the story of a slave.

By 1888, the population of Martinique had risen from about 163,000 people a decade earlier to 176,000. At the same time, natural disasters continued to plague the island. Much of Fort de France was devastated by a fire in 1890, and then the next year a hurricane killed some 400 people.

In the 1880s, the Paris architect Pierre-Henri Picq built the Schoelcher Library, an iron and glass structure that was exhibited in the Tuileries Gardens during the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle

, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. After the Exposition the building was shipped to Fort de France and reassembled there, the work being completed by 1893. Initially, the library contained the 10,000 books that Victor Schoelcher

had donated to the island. Today it houses over 250,000 and stands as a tribute to the man who led the movement to abolish slavery in Martinique. In 1895, Picq also built the Saint-Louis Cathedral in Fort-de-France.

destroyed the town of St. Pierre, killing almost all of its 29,000 inhabitants. The only survivors were a shoemaker and a prisoner who was saved by his position in a jail dungeon with only a single window. Because Saint Pierre was the commercial capital of the island, there were four banks in the city—the Banque de la Martinique, Banque Transatlantique

, a branch of the Colonial Bank of London, and the Crédit Foncier Colonial. All were destroyed. The town had to be completely rebuilt and lost its status as the commercial capital, a title which shifted to Fort-de-France

in 1906 caused further damage in Martinique, but mercifully no deaths. As construction began on the Panama Canal

, more than 5,000 Martiniquans left to work on the project.

Resettlement of Saint Pierre began in 1908. Even so, two years later the City of Saint Pierre was removed from the map of France with jurisdiction over the ruins transferring to Le Carbet

. Elsewhere, political opponents assassinated the mayor of Fort de France, Antoine Seger in 1908.

With war with Germany looming, in 1913 France enacted compulsory military service in the colony, and called on Martinique to send 1,100 men per year to France for training. When World War I finally came, 18,000 Martiniquans took part, of whom 1,306 died. During the war, the French government requisitioned Martinique's rum production for the use of the French Army

. Production doubled as sugar mills converted to distilleries, helping the recovery of the local economy.

With the collapse of the world market for sugar in 1921-22, cultivators sought a new crop. In 1928 they introduced bananas.

Mont Pelée became active in 1929, forcing the temporary evacuation of Saint Pierre. The Volcanological Observatory there did not get its first seismometer until some three years later.

In 1931, the Martiniquan Aimé Césaire

moved to Paris to attend the Lycée Louis-le-Grand

, the École Normale Supérieure

, and finally the Sorbonne

. While in Paris, Césaire met Léopold Senghor, then a poet but later Senegal

's first President. Césaire, Senghor, and Léon Damas

, with whom Césaire had gone to school in Martinique at the Lycée Schoelcher, together formulated the concept of négritude

, defined as an affirmation of pride in being black, and promoted it as a movement.

In 1933, André Aliker, the editor of Justice, the Communist newspaper, documented that a M. Aubéry, the wealthy, white owner of the Lareinty Company, had bribed the judges of the Court of Appeal to dismiss charges of tax fraud against him. That same year, Félix Eboué became the Acting Governor of the island, and an American, Frank Perret, established Le Musée Volcanologique at Saint Pierre.

In 1934, persons unknown kidnapped and murdered André Aliker; his body washed up on the beach with his arms tied behind him. Aimé Césaire, Senghor, Damas, and others, founded L'Etudiant, a Black student review.

In 1939, the French cruiser Jeanne d'Arc arrived late in the year with Admiral Georges Robert, High Commissioner of the Republic to the Antilles and Guiana. Aimé Césaire returned to Martinique. He became a teacher at the Lycee Schoelcher in Fort de France, where his students included Franz Fanon and Édouard Glissant

.

, with the US and Great Britain seeking to limit any impact of that stance on the war. The US did prepare plans for an invasion by an expeditionary force to capture the island, and at various times the US and Britain established blockades. For instance, from July to November 1940, the British cruisers and maintained a watch to ensure that the French aircraft carrier Béarn

and the other French naval vessels in Martinique did not slip away to Europe.

In June 1940, the French cruiser Émile Bertin

arrived in Martinique with 286 tons of gold from the Bank of France. The original intent was that Bank's gold reserve go to Canada for safekeeping, and a first shipment did go there. When France signed an armistice with Germany, plans changed and the second shipment was rerouted to Martinique. When it arrived in Martinique, Admiral Robert arranged for the storage of the gold in Fort Desaix

. Émile Bertin then stayed at Fort de France until Martinique declared for Charles de Gaulle

and the Free French forces. Essentially, in late 1941, Admiral Robert agreed to keep the French naval vessels immobilized, in return for the Allies not bombarding and invading the French Antilles.

In mid-1943, Admiral Robert returned to France via Puerto Rico

and Lisbon

, and Free French sympathizers took control of the gold at Fort Desaix and the French fleet.

In 1944, the American film director Howard Hawks

directed Humphrey Bogart

, Lauren Bacall

, Hoagy Carmichael

and Walter Brennan

in the film To Have and Have Not

. Hawks more-or-less based the film on a novel that Ernest Hemingway

had written in 1937. The essence of the plot is the conversion from neutrality to the Free French side of an American fishing boat captain operating out of Vichy-controlled Fort de France in 1940.

In 1945, Aimé Césaire

succeeded in getting elected Mayor of Fort de France and Deputy from Martinique to the French National Assembly

as a member of the Communist Party

. Césaire went on to remain mayor for 56 years. However, the Communist suppression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 disillusioned him, causing him to quit the Communist Party. As a member of the Assembly, he was one of the principal drafters of the 1946 law on departmentalizing former colonies, a role for which politicians favoring independence have often criticized him.

In 1947 the High Court of Justice in Versailles tried Admiral Robert for collaboration

. He received a sentence of 100 years at hard labor and national degradation for life. The Court released him from the hard labor after six months, and he received a pardon in 1957.

or DOM. Along with its fellow DOMs of Guadeloupe

, Réunion

, and French Guiana

, Martinique was intended to be legally identical to any department in the metropole. However, in reality, several key differences remained, particularly within social security payments and unemployment benefits.

French funding to the DOM has somewhat made up for the social and economic devastation of the slave trade and sugar crop monoculture. With French funding to Martinique, the island had one of the highest standards of living in the Caribbean. However, it remained dependent upon French aid, as when measured by what Martinique actually produced, it was one of the poorer islands in the region.

Martinique

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, with a land area of . Like Guadeloupe, it is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. To the northwest lies Dominica, to the south St Lucia, and to the southeast Barbados...

.

100-1450

The island was originally inhabited by Arawak and Carib peoples. Circa 130 CE, the first Arawaks are believed to have arrived from South America. In 295 CE, an eruption of Mount PeléeMount Pelée

Mount Pelée is an active volcano at the northern end of the island and French overseas department of Martinique in the Lesser Antilles island arc of the Caribbean. Its volcanic cone is composed of layers of volcanic ash and hardened lava....

resulted in the decimation of the island's population. Around 400 CE, the Arawaks returned and repopulated the island. Around 600 CE, the Caribs arrived. They exterminated the Arawaks and proceeded to settle on the island over the next few centuries.

1450-1599

Christopher ColumbusChristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

charted the island in 1493, making the region known to European interests, but it was not until June 15, 1502, on his fourth voyage, that he actually landed, leaving several pigs and goats on the island. However, the Spaniards ignored the island as other parts of the New World were of greater interest to them.

17th century

In 1635, Cardinal Richelieu created the Compagnie des Îles de l'AmériqueCompagnie des Îles de l'Amérique

The Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique, French for Company of the American Islands, was a French chartered company that in 1635 took over the administration of the French portion Saint-Christophe island from Compagnie de Saint-Christophe which was the only French settlement in the Caribbean at that...

(Company of the Isles of America, the successor to the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe

Compagnie de Saint-Christophe

The Compagnie de Saint-Christophe was a company created and chartered by French adventurers to exploit the island of Saint-Christophe, the present-day Saint Kitts and Nevis. In 1625, a French adventurer, Pierre Bélain sieur d'Esnambuc, landed on Saint-Christophe with a band of adventurers and some...

). The company contracted with Messrs l'Olive and Duplessis to occupy and govern on its behalf the Caribbean islands belonging to the French crown. This led on September 1, 1635, to Pierre Bélain d'Esnambuc

Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc

thumb|220px|Pierre Belain d'EsnambucPierre Bélain, Sieur d'Esnambuc was a French trader and adventurer in the Caribbean, who established the first permanent French colony, Saint-Pierre, on the island of Martinique in 1635....

landing on Martinique with eighty to one hundred French settlers from Saint Cristophe

Saint Kitts and Nevis

The Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis , located in the Leeward Islands, is a federal two-island nation in the West Indies. It is the smallest sovereign state in the Americas, in both area and population....

. They met some resistance that they were able to dispatch quickly because of their far superior weaponry and armor. They settled in the northwestern region that later became known as St. Pierre

Saint-Pierre, Martinique

Saint-Pierre is a town and commune of France's Caribbean overseas department of Martinique, founded in 1635 by Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc. Before the total destruction of Saint-Pierre in 1902 by a volcanic eruption, it was the most important city of Martinique culturally and economically, being known...

at the mouth of the Roxelane River, where they built Fort Saint Pierre.

The following year, d'Esnambuc fell ill and passed the command of the settlement to his nephew, Jacques Dyel du Parquet. At this time the colony's population numbered some 700 men. The settlers cleared the land around St. Pierre to grow crops. They grew manioc and potatoes were grown to live on and rocou, indigo

Indigo

Indigo is a color named after the purple dye derived from the plant Indigofera tinctoria and related species. The color is placed on the electromagnetic spectrum between about 420 and 450 nm in wavelength, placing it between blue and violet...

, tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

, and later cacao and cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

, for export. French and foreign merchants frequently came to the island to buy these exotic products, transforming Martinique into a modestly prosperous colony. The colonists also established another fort, Fort Saint Louis

Fort Saint Louis (Martinique)

Fort Saint Louis is a fortress on a peninsula at Fort-de-France, Martinique. Today the Fort is both a naval base and an Historic Monument. There are daily tours of the fort, though the portion that is still a naval base is off-limits.-Naval Base:...

in 1638. This fort, like Fort Saint Pierre, was little more than a wooden stockade. In 1640, the fort was improved to include a ditch, high stone walls and 26 cannons.

Over the next quarter of a century the French established full control of the island. They systematically killed the fiercely resisting Caribs as they expanded, forcing the survivors back to the Caravelle Peninsula in the Cabesterre (the leeward side of the island).

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

proclaimed "La Traite des Noirs", which authorized the forcible removal of Africans from their homeland and their transport to work as slaves

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

on the French sugar plantations. Ever since, a strong theme of Martiniquan culture

Culture of Martinique

As an overseas départment of France, Martinique's culture is French and Caribbean. Its former capital, Saint-Pierre , was often referred to as the Paris of the Lesser Antilles. Following French custom, many businesses close at midday, then reopen later in the afternoon. The official language is...

has been creolization

Creole peoples

The term Creole and its cognates in other languages — such as crioulo, criollo, créole, kriolu, criol, kreyol, kreol, kriulo, kriol, krio, etc. — have been applied to people in different countries and epochs, with rather different meanings...

or interaction between the French colonial settlers, known locally as békés, and the Africans they imported. For over two hundred years, slavery, and slave revolts, would be a major influence on the economy and politics of the island.

The French colonial settlers were peasants attracted by propaganda promising fortune and a life under the sun. The "volunteers" were indentured servants who had to work for their master for three years, after which they were promised their own land. However, the tiring work and hot climate resulted in few of the workers surviving their three years, with the result that constant immigration was necessary for maintaining the workforce. Still, under the directorship of du Parquet, Martinique's economy developed as it exported products to France and the neighboring English and Dutch colonies. In 1645, the Sovereign council was established with several powers, among them the right to grant titles of nobility to families in the islands. In 1648, the Company of the Isles of America started to wind up its affairs and in 1650 du Parquet bought the island.

In 1650 Father Jacques du Tetre built a still for converting the waste from the sugarcane

Sugarcane

Sugarcane refers to any of six to 37 species of tall perennial grasses of the genus Saccharum . Native to the warm temperate to tropical regions of South Asia, they have stout, jointed, fibrous stalks that are rich in sugar, and measure two to six metres tall...

mills into molasses, which became a major export industry.

In 1654, du Parquet allowed 250 Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

Jews

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

, who were fleeing Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

following the Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

conquest, to settle Martinique, where they engaged in the sugar trade. This was by far the most sought after product in Europe and the crop soon became Martinique's biggest export.

After the death of du Parquet, his widow ruled on behalf of his children until 1658, when Louis XIV resumed sovereignty over the island, paying an indemnity of £120,000 to the du Parquet children. At this time, Martinique's population numbered some 5,000 settlers and a few surviving Carib Indians. The Caribs

Carib Expulsion

The Carib Expulsion was the French-led ethnic cleansing that removed most of the Carib population in 1660 from present-day Martinique. This followed the French invasion in 1635 invasion and conquest of the Caribbean island that made it part of the French colonial empire.-History:The Carib people...

were eventually exterminated or exiled in 1660.

In 1658, Dominican Fathers

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

built an estate at Fonds Saint-Jacques. From 1693 to 1705, this was the home of Père Labat, the French Dominican priest who improved the distillery. A colorful character, he was also an explorer, architect, engineer, and historian, and fought as a soldier against the English.

In 1664, Louis transferred the island, this time to the newly-established Compagnie des Indes Occidentales. The next year, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo–Dutch War was part of a series of four Anglo–Dutch Wars fought between the English and the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries for control over the seas and trade routes....

, a Dutch fleet under Admiral Michel de Ruyter retired to Martinique to refit after the fleet's indecisive encounter with an English force off Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

. Two years later a hurricane devastated Martinique and Guadelope, killing some 2,000 people. This was the first of several natural disasters that would devastate the population of Martinique over the next few centuries.

In 1666 and 1667 the English unsuccessfully attacked. The Treaty of Breda (1667) ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo–Dutch War was part of a series of four Anglo–Dutch Wars fought between the English and the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries for control over the seas and trade routes....

and hence the hostilities.

In 1672, Louis XIV ordered the construction of a citadel, Fort Saint Louis

Fort Saint Louis (Martinique)

Fort Saint Louis is a fortress on a peninsula at Fort-de-France, Martinique. Today the Fort is both a naval base and an Historic Monument. There are daily tours of the fort, though the portion that is still a naval base is off-limits.-Naval Base:...

, at Fort Royal Bay to defend Martinique. The next year, the Compagnie des Indes Occidentales decided to establish a town at Fort Royal, even though the location was a malarial swamp. The Compagnie des Indes Occidentales failed in 1674, and the colony reverted to the direct administration of the French crown. Martinique's administration was in the hands of council. The King appointed two members: the Lieutenant-general and the administrator. They chose the other council members (the governor, the Attorney General and the ordinary judge). This organization lasted until 1685.

During the Third Anglo-Dutch War

Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo–Dutch War or Third Dutch War was a military conflict between England and the Dutch Republic lasting from 1672 to 1674. It was part of the larger Franco-Dutch War...

, de Ruyter returned to Martinique in 1674, this time with the intent to capture Fort Royal. Calm winds and French booms prevented him from sailing his fleet of 30 warships, nine supply ships, and 15 transports into the harbor. The French repulsed his attempt to land his 3,400 troops, causing him to loose 143 men, at a cost of 15 French lives.

In 1675 the first Governor General of the West Indies, Jean-Charles de Baas-Castelmore, arrived in Martinique and served until 1677. His successor was Charles de La Roche-Courbon, comte de Blénac, who served for the first time from 1677 to 1683. He drew up a plan for the city of Fort Royal and improving the fortifications of Fort Saint Louis

Fort Saint Louis (Martinique)

Fort Saint Louis is a fortress on a peninsula at Fort-de-France, Martinique. Today the Fort is both a naval base and an Historic Monument. There are daily tours of the fort, though the portion that is still a naval base is off-limits.-Naval Base:...

. de Blénac was responsible for the 10-year effort that resulted in the building of a 487 meter wall around the peninsula on which the Fort stood, the wall being four meters high and two meters thick, and cutting a ditch that separated from the town. de Blénac served as Governor General again from June 1684 to February 1691, and again from 24 Nov 1691 until his death in 1696.

The growth of the town resulted in the progressive clearing and draining of the mangrove

Mangrove

Mangroves are various kinds of trees up to medium height and shrubs that grow in saline coastal sediment habitats in the tropics and subtropics – mainly between latitudes N and S...

swamp. By 1681, Fort-Royal was the administrative, military and political capital of Martinique. Still, Saint Pierre, with its better harbor, remained the commercial capital.

In 1685, in France Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert was a French politician who served as the Minister of Finances of France from 1665 to 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His relentless hard work and thrift made him an esteemed minister. He achieved a reputation for his work of improving the state of French manufacturing...

promulgated the "Code des Noires" (Code concerning the Blacks), whose 60 articles would regulate slavery in the colonies. The code forbade some cruel acts, but institutionalized others and slavery itself, relegating the status of slaves to that of chattel.

Colbert also ordered the expulsion of the Jews from all the French islands. These Jews then moved to the Dutch island of Curaçao

Curaçao

Curaçao is an island in the southern Caribbean Sea, off the Venezuelan coast. The Country of Curaçao , which includes the main island plus the small, uninhabited island of Klein Curaçao , is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands...

, where they prospered. In 1692, Charles de La Roche-Courbon, Count of Blénac, the Governor and Lieutenant General of the French colonies in America, named Fort Royal as the capital city of Martinique.

In 1693 the English again unsuccessfully attacked Martinique.

1700-1788

In 1720, a French naval officer, Gabriel de Clieu, procured a coffee plant seedling from the Royal Botanical GardensJardin des Plantes

The Jardin des Plantes is the main botanical garden in France. It is one of seven departments of the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. It is situated in the 5ème arrondissement, Paris, on the left bank of the river Seine and covers 28 hectares .- Garden plan :The grounds of the Jardin des...

in Paris and transported it to Martinique. He transplanted it on the slopes of Mount Pelee

Mount Pelée

Mount Pelée is an active volcano at the northern end of the island and French overseas department of Martinique in the Lesser Antilles island arc of the Caribbean. Its volcanic cone is composed of layers of volcanic ash and hardened lava....

and was able to harvest his first crop in 1726, or shortly thereafter. By 1736, the number of slaves in Martinique had risen to 60,000 people. In 1750, Saint Pierre had about 15,000 inhabitants, and Fort Royal only about 4,000.

Britain captured the island

British expedition against Martinique

The British expedition against Martinique was a military action from January to February 1762, as part of the Seven Years' War.- Prelude :...

during the Seven Years' War

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

, holding it from 1762 to 1763. Following Britain's victory in the war

Great Britain in the Seven Years War

The Kingdom of Great Britain was one of the major participants in the Seven Years' War which lasted between 1756 and 1763. Britain emerged from the war as the world's leading colonial power having gained a number of new territories at the Treaty of Paris in 1763 and established itself as the...

there was a strong possibility the island would be annexed by them. However, the sugar trade made the island so valuable to the royal French government that at the Treaty of Paris (1763)

Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, often called the Peace of Paris, or the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763, by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement. It ended the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

, which ended the Seven Years War, they gave up all of Canada in order to regain Martinique as well as the neighboring island of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an archipelago located in the Leeward Islands, in the Lesser Antilles, with a land area of 1,628 square kilometres and a population of 400,000. It is the first overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. As with the other overseas departments, Guadeloupe...

. During the British occupation, Marie Josèph Rose Tascher de la Pagerie, the future Empress Josephine was born to a noble family living on Trois Ilets across the bay from Fort Royal. Also, 1762 saw a yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

epidemic

Epidemic

In epidemiology, an epidemic , occurs when new cases of a certain disease, in a given human population, and during a given period, substantially exceed what is expected based on recent experience...

and in 1763 the French established separate governments for Martinique and Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an archipelago located in the Leeward Islands, in the Lesser Antilles, with a land area of 1,628 square kilometres and a population of 400,000. It is the first overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. As with the other overseas departments, Guadeloupe...

.

August 2, 1766 saw the birth of Saint-Pierre de Louis Delgrès, a mixed-race free black who would serve in the French army and fight the British in 1794, before becoming the leader of the unsuccessful resistance in Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an archipelago located in the Leeward Islands, in the Lesser Antilles, with a land area of 1,628 square kilometres and a population of 400,000. It is the first overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. As with the other overseas departments, Guadeloupe...

against General Richepance, whom Napoléon had sent to restore slavery to that colony. On August 13 (in either 1766 or 1767) a hurricane - apparently accompanied by an earthquake - struck the island; 600-1600 were killed. Monsieur de la Pagerie, the father of the future Empress, was almost ruined. At the time, there were some 450 sugar mills in Martinique, and molasses was a major export. Four years later an earthquake shook the island. By 1774, when a decree ended indentured servitude for whites, there were some 18 to 19 million coffee trees on the island. In 1776, one of the most damaging hurricanes in Western history struck the island, killing 6000. Over 100 French and Dutch merchantmen were lost.

In 1779, the future Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joséphine de Beauharnais was the first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, and thus the first Empress of the French. Her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais had been guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she had been imprisoned in the Carmes prison until her release five days after Alexandre's...

, first Empress of the French, sailed for France to meet her husband for the first time. In 1782, Admiral de Grasse sailed from Martinique to rendezvous with Spanish forces in order to attack Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

. The subsequent battle of the Saintes

Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes took place over 4 days, 9 April 1782 – 12 April 1782, during the American War of Independence, and was a victory of a British fleet under Admiral Sir George Rodney over a French fleet under the Comte de Grasse forcing the French and Spanish to abandon a planned...

resulted in a massive defeat for the French at the hands of the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

.

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

The French RevolutionFrench Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

(1789) also had an impact on Trinidad

Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands and numerous landforms which make up the island nation of Trinidad and Tobago. It is the southernmost island in the Caribbean and lies just off the northeastern coast of Venezuela. With an area of it is also the fifth largest in...

when Martiniquan planters and their slaves emigrated there and started to grow sugar and cocoa. In Martinique, there was a small, unsuccessful slave rebellion in Saint Pierre. The French executed six of the ringleaders. On February 4, 1793, Jean Baptiste Dubuc signed an accord in Whitehall

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road in Westminster, in London, England. It is the main artery running north from Parliament Square, towards Charing Cross at the southern end of Trafalgar Square...

, London, putting Martinique under British jurisdiction until the French Monarchy could be re-established. In doing so he forestalled the spread of the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

to Martinique by giving the English an excuse to intervene. Notably, the accord guaranteed the continuation of slavery.

In 1794 the French Convention abolished slavery. However, before this decree could get to Martinique and be implemented, the British attacked the island and captured it. A British force under Admiral Sir John Jervis

John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent

Admiral of the Fleet John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent GCB, PC was an admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom...

and Lieutenant General Sir Charles Grey

Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey

Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey, KB PC was one of the most important British generals of the 18th century. He was the fourth son of Sir Henry Grey, 1st Baronet, of Howick in Northumberland. He served in the Seven Years' War, American War of Independence and French Revolutionary War...

captured Fort Royal and Fort Saint Louis

Fort Saint Louis (Martinique)

Fort Saint Louis is a fortress on a peninsula at Fort-de-France, Martinique. Today the Fort is both a naval base and an Historic Monument. There are daily tours of the fort, though the portion that is still a naval base is off-limits.-Naval Base:...

on March 22, and Fort Bourbon

Fort Desaix

Fort Desaix is a Vauban fort and one of four forts that protects Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique. The fort was built from 1768 to 1772 and sits on a hill, Morne Garnier, overlooking what was then Fort Royal...

two days later. At that point all resistance ceased. On March 30, 1794, the British occupation reinstated the Old Regime, including the Monarchy's Supreme Council and the seneschal

Seneschal

A seneschal was an officer in the houses of important nobles in the Middle Ages. In the French administrative system of the Middle Ages, the sénéchal was also a royal officer in charge of justice and control of the administration in southern provinces, equivalent to the northern French bailli...

's courts of Trinité, Marin

Marin

-Places:*Marin, Haute-Savoie, a commune in France*Le Marin, a commune in the French overseas department of Martinique*Marín, Nuevo León, a town and municipality in Mexico*Marín, Pontevedra, a municipality in Galicia, Spain*Marin County, California...

, and St Pierre

Saint-Pierre, Martinique

Saint-Pierre is a town and commune of France's Caribbean overseas department of Martinique, founded in 1635 by Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc. Before the total destruction of Saint-Pierre in 1902 by a volcanic eruption, it was the most important city of Martinique culturally and economically, being known...

. The Royalists regained possession of their properties and positions, slaves were returned to their masters, and emancipation was forbidden. The government also promulgated an ordinance banning all gatherings of blacks or meetings by slaves, and banned Carnival

Carnival

Carnaval is a festive season which occurs immediately before Lent; the main events are usually during February. Carnaval typically involves a public celebration or parade combining some elements of a circus, mask and public street party...

. However, the British did require an oath of allegiance to the King of England.

Six years later, in 1800, Jean Kina, an ex-slave from Dominica

Dominica

Dominica , officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island nation in the Lesser Antilles region of the Caribbean Sea, south-southeast of Guadeloupe and northwest of Martinique. Its size is and the highest point in the country is Morne Diablotins, which has an elevation of . The Commonwealth...

and aide-de-camp to a British officer, fled to Morne Lemaître and called on free blacks and slaves to join him in a rebellion in support of the rights of the free blacks. A number did so, leading Kina to occupy his position for over a year. When he marched on Port Royal

Port Royal

Port Royal was a city located at the end of the Palisadoes at the mouth of the Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1518, it was the centre of shipping commerce in the Caribbean Sea during the latter half of the 17th century...

though, a British force took over the position and negotiated his surrender in return for amnesty. The British transported Kina to England, where they held him in Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

.

In 1802, the British returned the island to the French with the Treaty of Amiens

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens temporarily ended hostilities between the French Republic and the United Kingdom during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was signed in the city of Amiens on 25 March 1802 , by Joseph Bonaparte and the Marquess Cornwallis as a "Definitive Treaty of Peace"...

. When France regained control of Martinique, Napoléon Bonaparte

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

reinstated slavery. Two years later, he married Martiniquan Josephine de Beauharnais

Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joséphine de Beauharnais was the first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, and thus the first Empress of the French. Her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais had been guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she had been imprisoned in the Carmes prison until her release five days after Alexandre's...

and crowned her Empress of France.

During the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, in 1804 the British established a fort at Diamond Rock

Diamond Rock

Diamond Rock is a 175 meter high basalt island located south of Fort-de-France, the main port of the Caribbean island of Martinique. The uninhabited island is about three kilometers from Pointe Diamant. The island gets its name from the reflections that its sides cast at certain hours of the day,...

, outside Fort de France, and garrisoned it with some 120 sailors and five cannons. The Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

commissioned the fort HMS Diamond Rock and from there were able for 17 months to harass vessels coming into the port. The French eventually sent a fleet of sixteen vessels that retook the island after a fierce bombardment.

The British again captured Martinique in 1809

Invasion of Martinique (1809)

The invasion of Martinique of 1809 was a successful British amphibious operation against the French West Indian island of Martinique that took place between 30 January and 24 February 1809 during the Napoleonic Wars...

, and held it until 1814. In 1813, a hurricane killed 3,000 people in Martinique. During Napoleon's 100 Days

Hundred Days

The Hundred Days, sometimes known as the Hundred Days of Napoleon or Napoleon's Hundred Days for specificity, marked the period between Emperor Napoleon I of France's return from exile on Elba to Paris on 20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII on 8 July 1815...

in 1815, he abolished the slave trade. At the same time the British briefly re-occupied Martinique. The British, who had abolished the slave trade in their empire in 1807, forced Napoleon's successor, Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII of France

Louis XVIII , known as "the Unavoidable", was King of France and of Navarre from 1814 to 1824, omitting the Hundred Days in 1815...

to retain the proscription, though it did not become truly effective until 1831.

1815-1899

A slave insurrection in 1822 resulted in two dead and seven injured. The government condemned 19 slaves to death, 10 to the galleys, six to whipping, and eight to helping with the executions.Martinique has suffered from earthquake

Earthquake

An earthquake is the result of a sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust that creates seismic waves. The seismicity, seismism or seismic activity of an area refers to the frequency, type and size of earthquakes experienced over a period of time...

s as well as hurricanes. In 1839, an earthquake believed to have measured 6.5 on the Richter

Richter

Richter can refer to:* the Richter magnitude scale, a scale measuring the strength of earthquakes.* Richter , an electro-rock band from Buenos Aires, Argentina.-Richter as a surname:...

scale killed some 400 to 700 people, caused severe damage in Saint Pierre, and almost totally destroyed Fort Royal. Fort Royal was rebuilt in wood, reducing the risk from earthquakes, but increasing the risk from fire. That same year, there were 495 sugar producers in Martinique, who produced some 25,900 tons of "white gold".

In February 1848, François Auguste Perrinon

François Perrinon

François Auguste Perrinon was born at St.-Pierre into a free black family during the slavery period of the colony, but sent to mainland France for his education. He enrolled in the École Polytechnique, with a specialization in naval artillery.In 1842, he was sent back to the Caribbean as part of...

became head of the Committee of Colonists of Martinique. He was a member of the Commission for the abolition of slavery, led by Victor Schoelcher

Victor Schoelcher

Victor Schoelcher was a French abolitionist writer in the 19th century and the main spokesman for a group from Paris who worked for the abolition of slavery, and formed an abolition society in 1834...

. On April 27, Schoelcher obtained a decree abolishing slavery in the French Empire. Perrinon was appointed Commissioner General of Martinique, and charged with the task of abolishing slavery there. However, he and the decree did not arrive in Martinique until June 3, by which time Governor Claude Rostoland had already abolished slavery. The imprisonment of a slave at Le Prêcheur

Le Prêcheur

Le Prêcheur is a village and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.-External links:*...

had led to a slave revolt on May 20; two days later Rostoland, under duress, had abolished slavery on the island to quell the revolt. That same year, following the establishment of the Second Republic

Second Republic

-Europe:* French Second Republic * Second Polish Republic * Second Hellenic Republic * Second Spanish Republic * Portuguese Second Republic, known as Estado Novo * Czechoslovak Second Republic...

, Fort Royal became Fort de France.

In 1851 a law was passed authorizing the creation of two colonial banks with the authority to issue banknotes. This led to the founding of the Bank of Martinique in Saint Pierre, and the Bank of Guadeloupe. (These banks would merge in 1967 to form the present-day Banque des Antilles Française).

Indentured laborers from India started to arrive in Martinique in 1853. Plantation owners recruited the Indians to replace the slaves, who once free, had fled the plantations. This led to the creation of the small but continuing Indian

Hinduism in Martinique

The history of Hinduism in Martinique sort of began with the importation of Indian laborers in the mid-19th century, and, although Hindus now comprise only 0.5% of the population, the religion is still practiced on the island today....

community in Martinique. This immigration repeated on a smaller scale the importation of Indians to such British colonies as British Guiana

Guyana

Guyana , officially the Co-operative Republic of Guyana, previously the colony of British Guiana, is a sovereign state on the northern coast of South America that is culturally part of the Anglophone Caribbean. Guyana was a former colony of the Dutch and of the British...

and Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago is an archipelagic state in the southern Caribbean, lying just off the coast of northeastern Venezuela and south of Grenada in the Lesser Antilles...

following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833. Towards the end of the century, 1000 Chinese also came as earlier they had come to Cuba

Chinese Cuban

A Chinese Cuban is a Cuban of Chinese ancestry who was born in or has immigrated to Cuba. They are part of the ethnic Chinese diaspora .-History:...

.

The city government in 1857-58 cleared and filled the flood channel encircling Fort de France. The channel had become an open sewer and hence a health hazard. The filled-in channel, La Levee, marked the northern boundary of the city.

Martinique got its second enduring financial institution in 1863 when the Crédit Foncier Colonial opened its doors in Saint Pierre. Its objective was to make long-term loans for the construction or modernization of sugar factories. It replaced the Crédit Colonial, which had been established in 1860, but seems hardly to have gotten going.

In 1868 construction work on the Radoub Basin port facilities at Fort de France finally was completed. The improvements to the port would enable Fort de France better to compete in trade and commerce with Saint Pierre

Saint-Pierre, Martinique

Saint-Pierre is a town and commune of France's Caribbean overseas department of Martinique, founded in 1635 by Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc. Before the total destruction of Saint-Pierre in 1902 by a volcanic eruption, it was the most important city of Martinique culturally and economically, being known...

.

In 1870, rising racial tensions led to the short-lived insurrection in southern Martinique and proclamation in Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France is the capital of France's Caribbean overseas department of Martinique. It is also one of the major cities in the Caribbean. Exports include sugar, rum, tinned fruit, and cacao.-Geography:...

of a Martiniquan Republic. The insurrection started with an altercation between a local béké (white) and a black tradesman. A crowd lynched the béke and during the insurrection many sugar factories were torched. The authorities restored order by temporarily imprisoning some 500 rebels in Martinique's forts. Seventy four were tried and found guilty, and the twelve principal leaders were shot to death. The authorities deported the rest to French Guiana

French Guiana

French Guiana is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department located on the northern Atlantic coast of South America. It has borders with two nations, Brazil to the east and south, and Suriname to the west...

or New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

.

By this time sugar cane fields covered some 57% of Martinique's arable land. Unfortunately, falling prices for sugar forced many small sugar works to merge. Producers turned to rum production in an attempt to improve their fortunes.

When France established the Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

in 1871, the colonies, Martinique among them, gained representation in the National Assembly.

In 1887, after visiting Panama

Panama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

, Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin was a leading French Post-Impressionist artist. He was an important figure in the Symbolist movement as a painter, sculptor, print-maker, ceramist, and writer...

spent some months with his friend Charles Laval

Charles Laval

Charles Laval was a French painter born March 17, 1862 in Paris and who died April 27, 1894. He is associated with the Synthetic movement and Pont-Aven School, and he was a contemporary and friend of Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh. Gauguin created a portrait of him in 1886 looking at one of...

, also a painter, in a cabin some two kilometers south of Saint Pierre. During this period Gauguin produced several paintings featuring Martinique. There is now a small Gauguin museum in Le Carbet

Le Carbet

Le Carbet is a village and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.-External links:*...

that has reproductions of his Martinique paintings. That same year Harper's Weekly

Harper's Weekly

Harper's Weekly was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor...

sent the author and translator Lafcadio Hearn

Lafcadio Hearn

Patrick Lafcadio Hearn , known also by the Japanese name , was an international writer, known best for his books about Japan, especially his collections of Japanese legends and ghost stories, such as Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things...

to Martinique for a short visit; he ended up staying for some two years. After his return to the United States he would publish two books, one an account of his daily life in Martinique and the other the story of a slave.

By 1888, the population of Martinique had risen from about 163,000 people a decade earlier to 176,000. At the same time, natural disasters continued to plague the island. Much of Fort de France was devastated by a fire in 1890, and then the next year a hurricane killed some 400 people.

In the 1880s, the Paris architect Pierre-Henri Picq built the Schoelcher Library, an iron and glass structure that was exhibited in the Tuileries Gardens during the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle

Exposition Universelle (1889)

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 was a World's Fair held in Paris, France from 6 May to 31 October 1889.It was held during the year of the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, an event traditionally considered as the symbol for the beginning of the French Revolution...

, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. After the Exposition the building was shipped to Fort de France and reassembled there, the work being completed by 1893. Initially, the library contained the 10,000 books that Victor Schoelcher

Victor Schoelcher

Victor Schoelcher was a French abolitionist writer in the 19th century and the main spokesman for a group from Paris who worked for the abolition of slavery, and formed an abolition society in 1834...

had donated to the island. Today it houses over 250,000 and stands as a tribute to the man who led the movement to abolish slavery in Martinique. In 1895, Picq also built the Saint-Louis Cathedral in Fort-de-France.

20th century

The abolition of slavery did not end racially charged labor strife. In 1900, a strike at a sugar factory owned by a Frenchman led to the police shooting dead 10 agricultural workers.Mount Pelée eruption

On May 8, 1902, a blast from the volcano Mont PeléeMount Pelée

Mount Pelée is an active volcano at the northern end of the island and French overseas department of Martinique in the Lesser Antilles island arc of the Caribbean. Its volcanic cone is composed of layers of volcanic ash and hardened lava....

destroyed the town of St. Pierre, killing almost all of its 29,000 inhabitants. The only survivors were a shoemaker and a prisoner who was saved by his position in a jail dungeon with only a single window. Because Saint Pierre was the commercial capital of the island, there were four banks in the city—the Banque de la Martinique, Banque Transatlantique

Banque Transatlantique

Banque Transatlantique is one of France's oldest private banks. It is unusual among private banks in having a strong focus on serving expatriates, diplomats and international civil servants apart from being the wealth management arm of its parent group...

, a branch of the Colonial Bank of London, and the Crédit Foncier Colonial. All were destroyed. The town had to be completely rebuilt and lost its status as the commercial capital, a title which shifted to Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France is the capital of France's Caribbean overseas department of Martinique. It is also one of the major cities in the Caribbean. Exports include sugar, rum, tinned fruit, and cacao.-Geography:...

Return to normality

A hurricane in 1903 killed 31 people and damaged the sugar crop and a strong earthquake off Saint LuciaSaint Lucia

Saint Lucia is an island country in the eastern Caribbean Sea on the boundary with the Atlantic Ocean. Part of the Lesser Antilles, it is located north/northeast of the island of Saint Vincent, northwest of Barbados and south of Martinique. It covers a land area of 620 km2 and has an...

in 1906 caused further damage in Martinique, but mercifully no deaths. As construction began on the Panama Canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

, more than 5,000 Martiniquans left to work on the project.

Resettlement of Saint Pierre began in 1908. Even so, two years later the City of Saint Pierre was removed from the map of France with jurisdiction over the ruins transferring to Le Carbet

Le Carbet

Le Carbet is a village and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.-External links:*...

. Elsewhere, political opponents assassinated the mayor of Fort de France, Antoine Seger in 1908.

With war with Germany looming, in 1913 France enacted compulsory military service in the colony, and called on Martinique to send 1,100 men per year to France for training. When World War I finally came, 18,000 Martiniquans took part, of whom 1,306 died. During the war, the French government requisitioned Martinique's rum production for the use of the French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

. Production doubled as sugar mills converted to distilleries, helping the recovery of the local economy.

Between the World Wars

In 1923 Saint Pierre was reestablished as a municipality. Two years later, in Fort de France, the municipal council approved the Mayor's proposal to redevelop the slum district of Terres Sainvilles as a "workers city". The council would sell the new housing to the residents for 40 semi-annual interest-free payments.With the collapse of the world market for sugar in 1921-22, cultivators sought a new crop. In 1928 they introduced bananas.

Mont Pelée became active in 1929, forcing the temporary evacuation of Saint Pierre. The Volcanological Observatory there did not get its first seismometer until some three years later.

In 1931, the Martiniquan Aimé Césaire

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire was a French poet, author and politician from Martinique. He was "one of the founders of the négritude movement in Francophone literature".-Student, educator, and poet:...

moved to Paris to attend the Lycée Louis-le-Grand

Lycée Louis-le-Grand

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand is a public secondary school located in Paris, widely regarded as one of the most rigorous in France. Formerly known as the Collège de Clermont, it was named in king Louis XIV of France's honor after he visited the school and offered his patronage.It offers both a...

, the École Normale Supérieure

École Normale Supérieure

The École normale supérieure is one of the most prestigious French grandes écoles...

, and finally the Sorbonne

Sorbonne

The Sorbonne is an edifice of the Latin Quarter, in Paris, France, which has been the historical house of the former University of Paris...

. While in Paris, Césaire met Léopold Senghor, then a poet but later Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

's first President. Césaire, Senghor, and Léon Damas

Léon Damas

Léon-Gontran Damas was a French poet and politician. He was one of the founders of the Négritude movement.-Biography:...

, with whom Césaire had gone to school in Martinique at the Lycée Schoelcher, together formulated the concept of négritude

Négritude

Négritude is a literary and ideological movement, developed by francophone black intellectuals, writers, and politiciansin France in the 1930s by a group that included the future Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor, Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, and the Guianan Léon Damas.The Négritude...

, defined as an affirmation of pride in being black, and promoted it as a movement.