Historic recurrence

Encyclopedia

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

. In the extreme, the concept hypothetically assumes the form of the Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence

Eternal return

Eternal return is a concept which posits that the universe has been recurring, and will continue to recur, in a self-similar form an infinite number of times across infinite time or space. The concept initially inherent in Indian philosophy was later found in ancient Egypt, and was subsequently...

, which has been written about in various forms since antiquity and was described in the 19th century by Heinrich Heine

Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine was one of the most significant German poets of the 19th century. He was also a journalist, essayist, and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of Lieder by composers such as Robert Schumann...

and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

.

Nevertheless, while it is often remarked that "History repeats itself," in cycles of less than cosmological

Physical cosmology

Physical cosmology, as a branch of astronomy, is the study of the largest-scale structures and dynamics of the universe and is concerned with fundamental questions about its formation and evolution. For most of human history, it was a branch of metaphysics and religion...

duration this cannot be strictly true. That was appreciated by Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

, who has been quoted as saying that "History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme."

In this interpretation of recurrence, as opposed perhaps to the Nietzschean interpretation, there is no metaphysics. Recurrences take place due to ascertainable circumstances and chains of causality

Causality

Causality is the relationship between an event and a second event , where the second event is understood as a consequence of the first....

. An example of the mechanism is the ubiquitous phenomenon of multiple independent discovery in science and technology, which has been described by Robert K. Merton

Robert K. Merton

Robert King Merton was a distinguished American sociologist. He spent most of his career teaching at Columbia University, where he attained the rank of University Professor...

and Harriet Zuckerman

Harriet Zuckerman

Harriet Zuckerman is an American sociologist who specializes in the sociology of science. She is Senior Vice President of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and professor emerita of Columbia University.-Life:...

.

In The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, G.W. Trompf traces historically recurring patterns of political thought and behavior in the west since antiquity. If history has lessons to impart, they are to be found par excellence in such recurring patterns.

Historic recurrences can sometimes induce a sense of "convergence," "resonance" or déjà vu

Déjà vu

Déjà vu is the experience of feeling sure that one has already witnessed or experienced a current situation, even though the exact circumstances of the prior encounter are uncertain and were perhaps imagined...

. Three examples are given under "Striking similarity."

Authors

Prior to PolybiusPolybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

' theory of historic recurrence, ancient western thinkers who had thought about recurrence had largely been concerned with cosmological rather than historic recurrence.

Western philosophers and historians who have discussed various concepts of historic recurrence include Polybius

Polybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

(ca. 200–118 BCE), Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Caesar Augustus. His literary style was Attistic — imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.-Life:...

(ca. 60–7 BCE), Saint Luke, Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli was an Italian historian, philosopher, humanist, and writer based in Florence during the Renaissance. He is one of the main founders of modern political science. He was a diplomat, political philosopher, playwright, and a civil servant of the Florentine Republic...

(1469–1527), Giambattista Vico

Giambattista Vico

Giovanni Battista ' Vico or Vigo was an Italian political philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist....

(1668–1744), Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee CH was a British historian whose twelve-volume analysis of the rise and fall of civilizations, A Study of History, 1934–1961, was a synthesis of world history, a metahistory based on universal rhythms of rise, flowering and decline, which examined history from a global...

(1889–1975).

An eastern concept that bears a kinship to western concepts of historic recurrence is the Chinese

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

concept of the Mandate of Heaven

Mandate of Heaven

The Mandate of Heaven is a traditional Chinese philosophical concept concerning the legitimacy of rulers. It is similar to the European concept of the divine right of kings, in that both sought to legitimaze rule from divine approval; however, unlike the divine right of kings, the Mandate of...

, by which an unjust ruler will lose the support of Heaven and be overthrown.

Paradigms

G.W. Trompf summarizes major views and paradigmParadigm

The word paradigm has been used in science to describe distinct concepts. It comes from Greek "παράδειγμα" , "pattern, example, sample" from the verb "παραδείκνυμι" , "exhibit, represent, expose" and that from "παρά" , "beside, beyond" + "δείκνυμι" , "to show, to point out".The original Greek...

s of historic recurrence:

Lessons

One such recurring theme was early offered by Poseidonius (ca. 135–51 BCE), who argued that dissipation of the old Roman

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

virtues had followed the removal of the Carthaginian

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

challenge to Rome's supremacy in the Mediterranean world. The theme that civilization

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

s flourish or fail according to their responses to the human and environment

Natural environment

The natural environment encompasses all living and non-living things occurring naturally on Earth or some region thereof. It is an environment that encompasses the interaction of all living species....

al challenges that they face, would be picked up two thousand years later by Toynbee

Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee CH was a British historian whose twelve-volume analysis of the rise and fall of civilizations, A Study of History, 1934–1961, was a synthesis of world history, a metahistory based on universal rhythms of rise, flowering and decline, which examined history from a global...

.

Dionysius, while praising Rome at the expense of her predecessors — Assyria

Assyria

Assyria was a Semitic Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid–23rd century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia , that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur...

, Media

Medes

The MedesThe Medes...

, Persia, and Macedonia — anticipated Rome's eventual decay. He thus implied the idea of recurring decay in the history of world empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

s — an idea that was to be developed by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

(1st century BCE) and Pompeius Trogus (1st century BCE).

By the late 5th century, Zosimus

Zosimus

Zosimus was a Byzantine historian, who lived in Constantinople during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I . According to Photius, he was a comes, and held the office of "advocate" of the imperial treasury.- Historia Nova :...

could see the writing on the Roman wall, and asserted that empires fell through internal disunity. He gave examples from the histories of Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

and Macedonia. In the case of each empire, growth had resulted from consolidation against an external enemy; Rome herself, in response to Hannibal's threat posed at Cannae

Cannae

Cannae is an ancient village of the Apulia region of south east Italy. It is a frazione of the comune of Barletta.-Geography:It is situated near the river Aufidus , on a hill on the right Cannae (mod. Canne della Battaglia) is an ancient village of the Apulia region of south east Italy. It is a...

, had risen to great-power status within a mere five decades. With Rome's world dominion, however, aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

had been supplanted by a monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

, which in turn tended to decay into tyranny; after Augustus Caesar, good rulers had alternated with tyrannical ones. The Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

, in its western and eastern sectors, had become a contending ground between contestants for power, while outside powers acquired an advantage. In Rome's decay, Zosimus saw history repeating itself in its general movements.

The ancients developed an enduring metaphor

Metaphor

A metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her eyes were glistening jewels." Metaphor may also be used for any rhetorical figures of speech that achieve their effects via...

for a polity

Polity

Polity is a form of government Aristotle developed in his search for a government that could be most easily incorporated and used by the largest amount of people groups, or states...

's evolution: they drew an analogy

Analogy

Analogy is a cognitive process of transferring information or meaning from a particular subject to another particular subject , and a linguistic expression corresponding to such a process...

between an individual human's life cycle

Life history theory

Life history theory posits that the schedule and duration of key events in an organism's lifetime are shaped by natural selection to produce the largest possible number of surviving offspring...

, and developments undergone by a body politic

Body politic

A polity is a state or one of its subordinate civil authorities, such as a province, prefecture, county, municipality, city, or district. It is generally understood to mean a geographic area with a corresponding government. Thomas Hobbes considered bodies politic in this sense in Leviathan...

. This metaphor was offered, in varying iterations, by Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

(106–43 BCE), Seneca

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and in one work humorist, of the Silver Age of Latin literature. He was tutor and later advisor to emperor Nero...

(ca. 1 BCE – 65 CE), Florus

Florus

Florus, Roman historian, lived in the time of Trajan and Hadrian.He compiled, chiefly from Livy, a brief sketch of the history of Rome from the foundation of the city to the closing of the temple of Janus by Augustus . The work, which is called Epitome de T...

(who lived in the times of Emperors Trajan

Trajan

Trajan , was Roman Emperor from 98 to 117 AD. Born into a non-patrician family in the province of Hispania Baetica, in Spain Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperor Domitian. Serving as a legatus legionis in Hispania Tarraconensis, in Spain, in 89 Trajan supported the emperor against...

and Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

), and Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus was a fourth-century Roman historian. He wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from Antiquity...

(between 325 and 330 – after 391 CE). This social-organism

Social organism

In sociology, the social organism is theoretical concept in which a society or social structure is viewed as a “living organism.” From this perspective, typically, the relation of social features, e.g. law, family, crime, etc., are examined as they interact with other features of society to meet...

metaphor would recur centuries later in the works of Émile Durkheim

Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim was a French sociologist. He formally established the academic discipline and, with Karl Marx and Max Weber, is commonly cited as the principal architect of modern social science and father of sociology.Much of Durkheim's work was concerned with how societies could maintain...

(1858–1917) and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer was an English philosopher, biologist, sociologist, and prominent classical liberal political theorist of the Victorian era....

(1820–1903).

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli was an Italian historian, philosopher, humanist, and writer based in Florence during the Renaissance. He is one of the main founders of modern political science. He was a diplomat, political philosopher, playwright, and a civil servant of the Florentine Republic...

, about to analyze the vicissitudes of Florentine and Italian

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

politics between 1434 and 1494, described recurrent oscillations between "order" and "disorder" within states:

Machiavelli accounts for this oscillation by arguing that virtù (valor and political effectiveness) produces peace, peace brings idleness (ozio), idleness disorder, and disorder rovina (ruin). In turn, from rovina springs order, from order virtù, and from this, glory and good fortune.

Machiavelli, as had the ancient Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

historian Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

, saw human nature

Human nature

Human nature refers to the distinguishing characteristics, including ways of thinking, feeling and acting, that humans tend to have naturally....

as remarkably stable—steady enough for the formulation of rules of political behavior. Machiavelli wrote in his Discorsi:

A recurring theme in world history

World History

World History, Global History or Transnational history is a field of historical study that emerged as a distinct academic field in the 1980s. It examines history from a global perspective...

is the rise and fall of great power

Great power

A great power is a nation or state that has the ability to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength and diplomatic and cultural influence which may cause small powers to consider the opinions of great powers before taking actions...

s and empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

s; even many, if not all, now medium-size or small countries have experienced expansionist periods in their histories. British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

historian Paul Kennedy

Paul Kennedy

Paul Michael Kennedy CBE, FBA , is a British historian at Yale University specialising in the history of international relations, economic power and grand strategy. He has published prominent books on the history of British foreign policy and Great Power struggles...

, in his study of The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict From 1500 to 2000, by Paul Kennedy, first published in 1987, explores the politics and economics of the Great Powers from 1500 to 1980 and the reason for their decline...

, concludes that

The Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana

George Santayana

George Santayana was a philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. A lifelong Spanish citizen, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States and identified himself as an American. He wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters...

observed that "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." Which raises the question whether those who can remember are not doomed, anyway, to be swept along by the majority who cannot.

Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

, having in mind the respective coups d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

of Napoleon I

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

(1799) and his nephew Napoleon III (1851), wrote acerbically in 1852: "Hegel remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history

World History

World History, Global History or Transnational history is a field of historical study that emerged as a distinct academic field in the 1980s. It examines history from a global perspective...

occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy

Tragedy

Tragedy is a form of art based on human suffering that offers its audience pleasure. While most cultures have developed forms that provoke this paradoxical response, tragedy refers to a specific tradition of drama that has played a unique and important role historically in the self-definition of...

, the second time as farce

Farce

In theatre, a farce is a comedy which aims at entertaining the audience by means of unlikely, extravagant, and improbable situations, disguise and mistaken identity, verbal humour of varying degrees of sophistication, which may include word play, and a fast-paced plot whose speed usually increases,...

."

British historian Niall Ferguson

Niall Ferguson

Niall Campbell Douglas Ferguson is a British historian. His specialty is financial and economic history, particularly hyperinflation and the bond markets, as well as the history of colonialism.....

, in Civilization: The West and the Rest (2011), warns that the rise and fall of civilizations "isn't one smooth, parabolic curve after another. Its shape is more like an exponentially steepening slope that quite suddenly drops off like a cliff.... [A] striking feature [of the history of past civilizations] is the speed with which most of them collapsed, regardless of the cause." Ferguson cites examples of such historic tipping points: the collapse of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

within a few decades in the early 5th century; the fall of the Inca Empire

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire , was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century...

within less than a decade in the early 16th century; the Ming Dynasty

Ming Dynasty

The Ming Dynasty, also Empire of the Great Ming, was the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty. The Ming, "one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history", was the last dynasty in China ruled by ethnic...

's fall in China over little more than a decade in the mid-17th century; the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

in 1991; the implosion of North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

n and Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

ern dictatorships in 2011. Similar catastrophic "tipping" processes occur in financial markets. "In the realm of power, as in the domain of the bond vigilantes, you're fine until you're not fine — and when you're not fine, you're suddenly in a terrifying death spiral."

Ferguson notes that in 1500 the average Chinese

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

was richer than the average North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

n, but by the late 1970s the American was over 20 times richer than the Chinese. "By the early 20th century, just a dozen Western empires — including the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

— controlled 58 percent of the world's land surface and population, and a staggering 74 percent of the global economy."

According to Ferguson, the West first surged ahead of the rest of the world after about 1500 thanks to a series of institutional innovations: competition among fragmented Europe's multiple monarchies and republics, which were in turn internally divided into competing corporate entities; the Scientific Revolution

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

, whose major 17th-century breakthroughs occurred in Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

; the rule of law and representative government; modern medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

; the consumer society; and the work ethic

Work ethic

Work ethic is a set of values based on hard work and diligence. It is also a belief in the moral benefit of work and its ability to enhance character. An example would be the Protestant work ethic...

, and higher savings rates, permitting sustained capital accumulation

Capital accumulation

The accumulation of capital refers to the gathering or amassing of objects of value; the increase in wealth through concentration; or the creation of wealth. Capital is money or a financial asset invested for the purpose of making more money...

.

Ferguson details the decline in the functioning of these institutions in the United States in recent decades and warns of the possibility of "imminent collapse." "Is there anything we can do to prevent such disasters? Social scientist Charles Murray calls for a 'civic great awakening' — a return to the original values of the American republic."

Striking similarity

One of the paradigms of recurrence thinking identified by G.W. Trompf involves "the isolation of any two specific events which bear a very striking similarity".Such events need not be separated remotely in time. Indeed, historians of science and technology such as Robert K. Merton

Robert K. Merton

Robert King Merton was a distinguished American sociologist. He spent most of his career teaching at Columbia University, where he attained the rank of University Professor...

and Harriet Zuckerman

Harriet Zuckerman

Harriet Zuckerman is an American sociologist who specializes in the sociology of science. She is Senior Vice President of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and professor emerita of Columbia University.-Life:...

have concluded that multiple independent identical discoveries

Multiple discovery

The concept of multiple discovery is the hypothesis that most scientific discoveries and inventions are made independently and more or less simultaneously by multiple scientists and inventors...

, carried out simultaneously or very nearly so by more than one researcher or group of researchers, are much more the rule than the exception.

Similar patterns have also been found in the social sciences

Social sciences

Social science is the field of study concerned with society. "Social science" is commonly used as an umbrella term to refer to a plurality of fields outside of the natural sciences usually exclusive of the administrative or managerial sciences...

and humanities

Humanities

The humanities are academic disciplines that study the human condition, using methods that are primarily analytical, critical, or speculative, as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences....

. In the film

Film

A film, also called a movie or motion picture, is a series of still or moving images. It is produced by recording photographic images with cameras, or by creating images using animation techniques or visual effects...

world, there are many instances of two or more films with similar plots or themes having been released within a close period of time.

Below are three examples of recurrence drawn from general history

World History

World History, Global History or Transnational history is a field of historical study that emerged as a distinct academic field in the 1980s. It examines history from a global perspective...

.

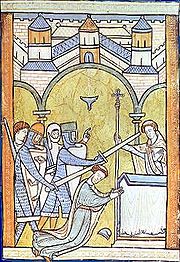

Kings kill bishops, create saints

Conflict between churchReligion-supporting organization

Religious activities generally need some infrastructure to be conducted. For this reason, there generally exist religion-supporting organizations, which are some form of organization that manage:* the upkeep of places of worship, e.g...

and state

State (polity)

A state is an organized political community, living under a government. States may be sovereign and may enjoy a monopoly on the legal initiation of force and are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union...

is an ancient theme, with examples found in civilizations as widely scattered in time and space as ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

(as with Akhenaten

Akhenaten

Akhenaten also spelled Echnaton,Ikhnaton,and Khuenaten;meaning "living spirit of Aten") known before the fifth year of his reign as Amenhotep IV , was a Pharaoh of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt who ruled for 17 years and died perhaps in 1336 BC or 1334 BC...

), medieval Europe and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

.

The story of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

’s Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion...

, and of his martyrdom in 1170 at the behest of King Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

, is familiar to the world. A pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England and forms part of a World Heritage Site....

provided the ostensible occasion for Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

’s Canterbury Tales. Becket’s martyrdom was reprised in T.S. Eliot’s verse drama, Murder in the Cathedral

Murder in the Cathedral

Murder in the Cathedral is a verse drama by T. S. Eliot that portrays the assassination of Archbishop Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170, first performed in 1935...

. In 1964 Jean Anouilh

Jean Anouilh

Jean Marie Lucien Pierre Anouilh was a French dramatist whose career spanned five decades. Though his work ranged from high drama to absurdist farce, Anouilh is best known for his 1943 play Antigone, an adaptation of Sophocles' Classical drama, that was seen as an attack on Marshal Pétain's...

’s play, Becket

Becket

Becket or The Honor of God is a play written in French by Jean Anouilh. It is a depiction of the conflict between Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England leading to Becket's murder in 1170. It contains many historical inaccuracies, which the author acknowledged.-Background:Anouilh's...

, was adapted as a film starring Richard Burton

Richard Burton

Richard Burton, CBE was a Welsh actor. He was nominated seven times for an Academy Award, six of which were for Best Actor in a Leading Role , and was a recipient of BAFTA, Golden Globe and Tony Awards for Best Actor. Although never trained as an actor, Burton was, at one time, the highest-paid...

and Peter O’Toole.

Less familiar to the world is the story of Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

’s Saint Stanisław Szczepanowski and of his martyrdom nine decades earlier, in 1079, personally by King Bolesław the Generous

Bolesław II the Generous

Bolesław II the Generous, also known as the Bold and the Cruel , was Duke of Poland and third King of Poland .He was the eldest son of Casimir I the Restorer and Maria Dobroniega, daughter of Grand Duke Vladimir I of Kiev....

.

In 1071, Stanisław of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów, or Stanisław Szczepanowski, was a Bishop of Kraków known chiefly for having been martyred by the Polish king Bolesław II the Bold...

became one of the earliest native Polish

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

s of the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

, as Bishop of Kraków, and an advisor to Bolesław

Bolesław II the Generous

Bolesław II the Generous, also known as the Bold and the Cruel , was Duke of Poland and third King of Poland .He was the eldest son of Casimir I the Restorer and Maria Dobroniega, daughter of Grand Duke Vladimir I of Kiev....

, Duke of Poland. Bishop Stanisław's achievements included re-establishing a metropolitan see at Gniezno

Gniezno

Gniezno is a city in central-western Poland, some 50 km east of Poznań, inhabited by about 70,000 people. One of the Piasts' chief cities, it was mentioned by 10th century A.D. sources as the capital of Piast Poland however the first capital of Piast realm was most likely Giecz built around...

. This was a precondition for Duke Bolesław's coronation

Coronation

A coronation is a ceremony marking the formal investiture of a monarch and/or their consort with regal power, usually involving the placement of a crown upon their head and the presentation of other items of regalia...

as King of Poland, which took place in 1076 — the first Polish coronation held at Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

, the country's capital from 1038.

Over the next three years, relations between Bishop Stanisław and King Bolesław II the Bold soured over a dispute concerning Church property and over the Bishop's criticism of the King's conduct in office. Eventually the Bishop excommunicated

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

the King. The King retaliated by accusing the Bishop of treason and in 1079 — when the King's henchmen dared not touch the Bishop — personally slew him as the Bishop celebrated mass.

Stanislaus of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów, or Stanisław Szczepanowski, was a Bishop of Kraków known chiefly for having been martyred by the Polish king Bolesław II the Bold...

's murder stirred outrage throughout Poland and led to the dethronement of King Bolesław II the Bold, who was forced to seek refuge in Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

. In 1253, 174 years after Bishop Stanisław's martyrdom, he was canonized, becoming Poland's first native saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

— St. Stanisław Szczepanowski

Stanislaus of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów, or Stanisław Szczepanowski, was a Bishop of Kraków known chiefly for having been martyred by the Polish king Bolesław II the Bold...

.

Nine decades after the martyrdom of Saint Stanisław, in 1170, something similar happened in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

:

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion...

had carried out important missions to Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

for Theobald

Theobald of Bec

Theobald was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 to 1161. He was a Norman; his exact birth date is unknown. Some time in the late 11th or early 12th century Theobald became a monk at the Abbey of Bec, rising to the position of abbot in 1137. King Stephen of England chose him to be Archbishop of...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, who subsequently recommended him to England's King Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

for the post of Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

. Upon his appointment, Becket became a boon companion to the King and enforced the Danegeld

Danegeld

The Danegeld was a tax raised to pay tribute to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the geld or gafol in eleventh-century sources; the term Danegeld did not appear until the early twelfth century...

taxes, creating resentment among affected English churchmen.

After Becket's patron, Archbishop Theobald, died in 1161, King Henry raised his friend Becket to the primacy

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

on the assumption that Becket would support him in curtailing church power. But no sooner had Becket been installed as England's primate

Primate (religion)

Primate is a title or rank bestowed on some bishops in certain Christian churches. Depending on the particular tradition, it can denote either jurisdictional authority or ceremonial precedence ....

than he switched loyalties and became as zealous in protecting the privileges of the Church as he had previously been in enforcing King Henry's prerogatives.

King Henry sought to abolish certain of the clergy's privileges that exempted them from the jurisdiction of the civil courts, and to introduce some royal control over the decisions of ecclesiastic courts. Archbishop Becket withheld his agreement to this

Constitutions of Clarendon

The Constitutions of Clarendon were a set of legislative procedures passed by Henry II of England in 1164. The Constitutions were composed of 16 articles and represent an attempt to restrict ecclesiastical privileges and curb the power of the Church courts and the extent of Papal authority in England...

. After several years, the tensions between them culminated on December 29, 1170, in the Archbishop's murder by four of the King's knights at Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England and forms part of a World Heritage Site....

as Becket attended Vespers

Vespers

Vespers is the evening prayer service in the Western Catholic, Eastern Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran liturgies of the canonical hours...

.

Henry II, unlike Poland's King Bolesław II the Bold, did not lose his throne over the Archbishop's murder. Becket came to be venerated as a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

, and within three years had been canonized a saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

. In 1174, during the Revolt of 1173–1174, King Henry humbled himself with public penance

Penance

Penance is repentance of sins as well as the proper name of the Roman Catholic, Orthodox Christian, and Anglican Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation/Confession. It also plays a part in non-sacramental confession among Lutherans and other Protestants...

at Becket's tomb. In 1189 the King was defeated in battle by his own son, Richard the Lionheart, and died two days later.

Islands repel invaders, hurricanes defeat fleets

Two islandIsland

An island or isle is any piece of sub-continental land that is surrounded by water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, cays or keys. An island in a river or lake may be called an eyot , or holm...

monarchies

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

, Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

and England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, have often been characterized as insular, xenophobic

Xenophobia

Xenophobia is defined as "an unreasonable fear of foreigners or strangers or of that which is foreign or strange". It comes from the Greek words ξένος , meaning "stranger," "foreigner" and φόβος , meaning "fear."...

, reserved and formal. Both these countries have been the first to industrialize, off the coasts of their respective continents. Both have experienced invasion

Invasion

An invasion is a military offensive consisting of all, or large parts of the armed forces of one geopolitical entity aggressively entering territory controlled by another such entity, generally with the objective of either conquering, liberating or re-establishing control or authority over a...

s, have been threatened by formidable empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

s, and have gone on to establish their own empires.

Emperor of China

The Emperor of China refers to any sovereign of Imperial China reigning between the founding of Qin Dynasty of China, united by the King of Qin in 221 BCE, and the fall of Yuan Shikai's Empire of China in 1916. When referred to as the Son of Heaven , a title that predates the Qin unification, the...

, Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan , born Kublai and also known by the temple name Shizu , was the fifth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire from 1260 to 1294 and the founder of the Yuan Dynasty in China...

, grandson of the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan , born Temujin and occasionally known by his temple name Taizu , was the founder and Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, which became the largest contiguous empire in history after his death....

, demanded that Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

submit to Mongol rule. Having met with rebuffs, in 1274 he sent out a fleet of 300 large vessels and perhaps 500 smaller ones, carrying 15,000 Mongol and Chinese

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, and 8,000 Korea

Korea

Korea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

n, warriors. On November 19, 1274, they landed at Hakata Bay on the Japanese island of Kyūshū

Kyushu

is the third largest island of Japan and most southwesterly of its four main islands. Its alternate ancient names include , , and . The historical regional name is referred to Kyushu and its surrounding islands....

, and next day fought the Battle of Bun'ei

Battle of Bun'ei

The , also known as the First Battle of Hakata Bay was the first attempt by the Yuan Dynasty founded by the Mongols to invade Japan. After conquering the Tsushima Island and Iki, Kublai Khan's fleet moved on to Japan proper, landing at Hakata Bay, a short distance from Kyūshū's administrative...

, also known as the "Battle of Hakata Bay." The Mongols, though outnumbered, held out all day but that night were persuaded by a storm to retreat.

In the spring of 1281, Kublai Khan made a second attempt to conquer Japan. After a poorly-coordinated false start, in the summer the combined Korean and Chinese fleet captured Iki-shima and proceeded on to Kyūshū. In several skirmishes known as the Battle of Kōan

Battle of Koan

The ', also known as the Second Battle of Hakata Bay, was the second attempt by the Yuan Dynasty founded by the Mongols to invade Japan...

, or the Second Battle of Hakata Bay, the Mongol forces were driven back to their ships. A massive typhoon—the famous kamikaze

Kamikaze

The were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, designed to destroy as many warships as possible....

("divine wind")—now assaulted Kyūshū for two days, destroying much of the Mongol fleet.

Three centuries later, storms again intervened to seal the fate of an attempt to subjugate an island monarchy at the opposite end of the Eurasian landmass

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

:

Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

's King Philip II

Philip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

was intent on stopping English

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

depredations against his treasure fleet

Spanish treasure fleet

The Spanish treasure fleets was a convoy system adopted by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to 1790...

s from Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

and Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

, and English assistance to Dutch rebels against Spanish rule in the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

. The Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

, in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

, gave his blessing to an undertaking that promised to restore Anglican England to the Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

fold.

On May 28, 1588, a Spanish Armada

Spanish Armada

This article refers to the Battle of Gravelines, for the modern navy of Spain, see Spanish NavyThe Spanish Armada was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia in 1588, with the intention of overthrowing Elizabeth I of England to stop English...

of 130 ships set sail from Spanish-controlled Lisbon

Lisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

for the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

. The Armada's charge was to protect a fleet of barges that were to carry a 16,000-strong invasion force to England. At midnight of July 28, 1588, as the Armada lay at anchor off Calais

Calais

Calais is a town in Northern France in the department of Pas-de-Calais, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's capital is its third-largest city of Arras....

, not far from the Spanish army at Dunkirk, the English set eight pitch-and gunpowder-filled ships alight and sent them downwind among the tightly-packed Spanish fleet. Many Spanish ships cut their cables in order to escape. The 55 lighter, more maneuverable English ships, armed with new longer-range artillery, could now engage the scattered Spanish ships individually.

Next day the English attacked. In the wake of the ensuing indecisive Battle of Gravelines, the Spanish, unaware that the English were short of ammunition, sailed north, pursued by the bluffing English fleet. The English followed the Armada well up the Scottish

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

coast before disengaging for lack of ammunition.

The Spanish fleet sailed on around Scotland and Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

into the North Atlantic. There it ran into a hurricane, which scattered the fleet and drove two dozen ships onto the Irish coast. Ultimately 67 ships—a mere half of the original Spanish Armada—survived to limp back to Spain.

The Spanish army never crossed the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

to invade England. Much as Kublai Khan might have, King Philip lamented: "I sent the Armada against men, not [the] winds and waves."

Gods return, civilizations fall

The peoples that inhabited areas of the world outside the three conjoined continents of AfricaAfrica

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, Asia

Asia

Asia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

and Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

had not taken part in the peaceful and warlike exchanges of people, goods, technologies

Technology

Technology is the making, usage, and knowledge of tools, machines, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or perform a specific function. It can also refer to the collection of such tools, machinery, and procedures. The word technology comes ;...

and idea

Idea

In the most narrow sense, an idea is just whatever is before the mind when one thinks. Very often, ideas are construed as representational images; i.e. images of some object. In other contexts, ideas are taken to be concepts, although abstract concepts do not necessarily appear as images...

s that had been going on for thousands of years in the "Old World

Old World

The Old World consists of those parts of the world known to classical antiquity and the European Middle Ages. It is used in the context of, and contrast with, the "New World" ....

." Hence these peoples, isolated from the tri-continental system, were particularly vulnerable to conquest and devastation by guns, germs and steel. There was, however, yet another factor that may have added to their vulnerability: their religious

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

belief

Belief

Belief is the psychological state in which an individual holds a proposition or premise to be true.-Belief, knowledge and epistemology:The terms belief and knowledge are used differently in philosophy....

s.

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

's governor, the Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

conquistador

Conquistador

Conquistadors were Spanish soldiers, explorers, and adventurers who brought much of the Americas under the control of Spain in the 15th to 16th centuries, following Europe's discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492...

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca was a Spanish Conquistador who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of mainland Mexico under the rule of the King of Castile in the early 16th century...

set sail with 11 ships and 600 men for Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

in search of gold and empire. In Yucatán

Yucatán

Yucatán officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Yucatán is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 106 municipalities and its capital city is Mérida....

he found two interpreters — one, the Doña Marina who has come down in Mexican history as La Malinche

La Malinche

La Malinche , known also as Malintzin, Malinalli or Doña Marina, was a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, who played a role in the Spanish conquest of Mexico, acting as interpreter, advisor, lover and intermediary for Hernán Cortés...

, and who was to play a crucial role in Cortés' career.

On Good Friday

Good Friday

Good Friday , is a religious holiday observed primarily by Christians commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and his death at Calvary. The holiday is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum on the Friday preceding Easter Sunday, and may coincide with the Jewish observance of...

, 1519, the expedition put in at a harbor where Cortés founded, as a base of operations, a town appropriately named La Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz ("The Rich City of the True Cross"—now Veracruz

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave , is one of the 31 states that, along with the Federal District, comprise the 32 federative entities of Mexico. It is divided in 212 municipalities and its capital city is...

). Soon ambassadors arrived from Tenochtitlán, the capital of Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II

Moctezuma II

Moctezuma , also known by a number of variant spellings including Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma and referred to in full by early Nahuatl texts as Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, was the ninth tlatoani or ruler of Tenochtitlan, reigning from 1502 to 1520...

, who hoped to keep Cortés at bay with gifts of gold. Cortés subsequently claimed to have learned at this time that he was suspected of being the feathered-serpent god Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl is a Mesoamerican deity whose name comes from the Nahuatl language and has the meaning of "feathered serpent". The worship of a feathered serpent deity is first documented in Teotihuacan in the first century BCE or first century CE...

or an emissary of that legendary god-king, who was predicted to return one day to reclaim his city in a One-Reed year of the Mexica

Mexica

The Mexica were a pre-Columbian people of central Mexico.Mexica may also refer to:*Mexica , a board game designed by Wolfgang Kramer and Michael Kiesling*Mexica , a 2005 novel by Norman Spinrad...

calendar—which year chanced, in that particular 52-year period, to be the current year, 1519.

To ensure the loyalty of his expedition's members, Cortés scuttled all but one of his ships, then in August led his band inland toward Tenochtitlán, then one of the greatest cities on earth. Having learned that many of the peoples who had been subjugated by the Aztecs hated their overlords, Cortés hoped to recruit them to his cause.

Ultimately, aided by his polyglot

Polyglot (person)

A polyglot is someone with a high degree of proficiency in several languages. A bilingual person can speak two languages fluently, whereas a trilingual three; above that the term multilingual may be used.-Hyperpolyglot:...

political adviser La Malinche

La Malinche

La Malinche , known also as Malintzin, Malinalli or Doña Marina, was a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, who played a role in the Spanish conquest of Mexico, acting as interpreter, advisor, lover and intermediary for Hernán Cortés...

, by the Aztecs' vassal tribes which Cortés terrorized into lending him military support, by his European firearms and other steel weapons, by his horses and war dogs, by smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

previously unknown to the Western Hemisphere

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere or western hemisphere is mainly used as a geographical term for the half of the Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian and east of the Antimeridian , the other half being called the Eastern Hemisphere.In this sense, the western hemisphere consists of the western portions...

, and by his own ruthless perfidy, Cortés conquered Mexico. For Moctezuma

Moctezuma II

Moctezuma , also known by a number of variant spellings including Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma and referred to in full by early Nahuatl texts as Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, was the ninth tlatoani or ruler of Tenochtitlan, reigning from 1502 to 1520...

had hesitated until too late to act decisively against the pale-skinned, bearded supposed god Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl is a Mesoamerican deity whose name comes from the Nahuatl language and has the meaning of "feathered serpent". The worship of a feathered serpent deity is first documented in Teotihuacan in the first century BCE or first century CE...

, had been taken hostage

Hostage

A hostage is a person or entity which is held by a captor. The original definition meant that this was handed over by one of two belligerent parties to the other or seized as security for the carrying out of an agreement, or as a preventive measure against certain acts of war...

by Cortés, and had been killed by his own people as but one of the early victims of his country's conquest.

Two and a half centuries later, a similar story would begin to play itself out in Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

:

Hawaii

Hawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

an mythology

Mythology

The term mythology can refer either to the study of myths, or to a body or collection of myths. As examples, comparative mythology is the study of connections between myths from different cultures, whereas Greek mythology is the body of myths from ancient Greece...

, the fertility god Lono

Lono

In Hawaiian mythology, the deity Lono is associated with fertility, agriculture, rainfall, and music. In one of the many Hawaiian legends of Lono, he is a fertility and music god who descended to Earth on a rainbow to marry Laka. In agricultural and planting traditions, Lono was identified with...

had descended to Earth on a rainbow to marry the fertility goddess Laka

Laka

In Hawaiian mythology, Laka is the name of a popular hero from Polynesian mythology....

. Lono was also the god of peace

Peace

Peace is a state of harmony characterized by the lack of violent conflict. Commonly understood as the absence of hostility, peace also suggests the existence of healthy or newly healed interpersonal or international relationships, prosperity in matters of social or economic welfare, the...

, and it was in his honor that the annual four-month Makahiki

Makahiki

The Makahiki season was the ancient Hawaiian New Year festival, in honor of the god Lono of the Hawaiian religion.It was a holiday covering four consecutive lunar months, approximately from October or November through February or March. Thus it might be thought of as including the equivalent of...

festival was held, during which war

War

War is a state of organized, armed, and often prolonged conflict carried on between states, nations, or other parties typified by extreme aggression, social disruption, and usually high mortality. War should be understood as an actual, intentional and widespread armed conflict between political...

was kapu

Kapu

Kapu refers to the ancient Hawaiian code of conduct of laws and regulations. The kapu system was universal in lifestyle, gender roles, politics, religion, etc. An offense that was kapu was often a corporal offense, but also often denoted a threat to spiritual power, or theft of mana. Kapus were...

(taboo). Lono eventually left Hawaii, promising to return on a floating island.

The first Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an to visit the Hawaiian Islands

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets, and undersea seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some 1,500 miles from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll...

, Captain James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

, during his third great voyage of exploration

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

, landed in 1778 at Kauai

Kauai

Kauai or Kauai, known as Tauai in the ancient Kaua'i dialect, is geologically the oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands. With an area of , it is the fourth largest of the main islands in the Hawaiian archipelago, and the 21st largest island in the United States. Known also as the "Garden Isle",...

. Departing the Hawaiian Islands, which he named the "Sandwich Islands," Cook proceeded to explore the coast of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

from California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

to the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

.

In 1779 Cook returned to the Hawaiian Islands. He arrived at the "Big Island" of Hawaii during the annual Makahiki

Makahiki

The Makahiki season was the ancient Hawaiian New Year festival, in honor of the god Lono of the Hawaiian religion.It was a holiday covering four consecutive lunar months, approximately from October or November through February or March. Thus it might be thought of as including the equivalent of...

peace festival. His ship, HMS Resolution

HMS Resolution (Cook)

HMS Resolution was a sloop of the Royal Navy, and the ship in which Captain James Cook made his second and third voyages of exploration in the Pacific...

— more particularly, its mast formation, sails and rigging — put some Hawaiians in mind of their god Lono

Lono

In Hawaiian mythology, the deity Lono is associated with fertility, agriculture, rainfall, and music. In one of the many Hawaiian legends of Lono, he is a fertility and music god who descended to Earth on a rainbow to marry Laka. In agricultural and planting traditions, Lono was identified with...

returning on a floating island. Moreover, Cook's route around the island before making landfall paralleled that of the processions that took place around the island during the Lono festival. Consequently some Hawaiians took Captain Cook for the returning god Lono, and he and his men were fêted accordingly.

After a couple weeks' sojourn, Cook set sail to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after the departure from Hawaii Island, the Resolutions foremast broke and Cook's two ships, Resolution and Discovery, returned to Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona.Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples, and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places listings on...

for repairs in what was now the "war

War