Haymarket affair

Encyclopedia

The Haymarket affair was a demonstration and unrest that took place on Tuesday May 4, 1886, at the Haymarket Square in Chicago

. It began as a rally in support of striking

workers. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb

at police

as they dispersed the public meeting. The bomb blast and ensuing gunfire

resulted in the deaths of eight police officers, mostly from friendly fire

, and an unknown number of civilians. In the internationally publicized legal proceedings that followed, eight anarchists

were tried for murder. Five men were convicted, of whom four were executed and one committed suicide

in prison, although the prosecution conceded none of the defendants had thrown the bomb.

The Haymarket affair is generally considered significant for the origin of international May Day

observances for workers. In popular literature, this event inspired the caricature of "a bomb-throwing anarchist." The causes of the incident are still controversial. The deeply polarized attitudes separating business and working class

people in late 19th-century Chicago are generally acknowledged as having precipitated the tragedy and its aftermath. The site of the incident was designated a Chicago Landmark

on March 25, 1992. The Haymarket Martyrs' Monument in nearby Forest Park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

and designated a National Historic Landmark

on February 18, 1997.

unanimously set May 1, 1886, as the date by which the eight-hour work day

would become standard. As the chosen date approached, U.S. labor unions prepared for a general strike

in support of the eight-hour day.

On Saturday, May 1, rallies were held throughout the United States. There were an estimated 10,000 demonstrators in New York City

and 11,000 in Detroit. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin

, some 10,000 workers turned out. The movement's center was in Chicago, where an estimated 40,000 workers went on strike. Albert Parsons

was an anarchist

and founder of the International Working People's Association

(IWPA). Parsons, with his wife Lucy

and their children, led a march of 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue

. Another 10,000 men employed in the lumber yards held a separate march in Chicago. Estimates of the number of striking workers across the U.S. range from 300,000 to half a million.

On May 3, striking workers in Chicago met near the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company plant. Union molders at the plant had been locked out

since early February and the predominantly Irish-American workers at McCormick had come under attack from Pinkerton

guards during an earlier strike action in 1885. This event, along with the eight-hour militancy of McCormick workers, had gained the strikers some respect and notoriety around the city. By the time of the 1886 general strike, strikebreaker

s entering the McCormick plant were under protection from a garrison of 400 police officers. Although half of the replacement workers defected to the general strike on May 1, McCormick workers continued to harass strikebreaker

s as they crossed the picket lines.

Speaking to a rally outside the plant on May 3, August Spies

advised the striking workers to "hold together, to stand by their union, or they would not succeed." Well-planned and coordinated, the general strike to this point had remained largely nonviolent. When the end-of-the-workday bell sounded, however, a group of workers surged to the gates to confront the strikebreakers. Despite calls by Spies for the workers to remain calm, gunfire erupted as police fired on the crowd. In the end, two McCormick workers were killed (although some newspaper accounts said there were six fatalities). Spies would later testify, "I was very indignant. I knew from experience of the past that this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement."

Outraged by this act of police violence, local anarchists quickly printed and distributed fliers calling for a rally the following day at Haymarket Square (also called the Haymarket), which was then a bustling commercial center near the corner of Randolph Street and Desplaines Street. Printed in German

and English, the fliers alleged police had murdered the strikers on behalf of business interests and urged workers to seek justice. The first batch of fliers contain the words Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force! When Spies saw the line, he said he would not speak at the rally unless the words were removed from the flier. All but a few hundred of the fliers were destroyed, and new fliers were printed without the offending words. More than 20,000 copies of the revised flier were distributed.

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies

spoke to the large crowd while standing in an open wagon on Des Plaines Street while a large number of on-duty police officers watched from nearby. According to witnesses, Spies began by saying the rally was not meant to incite violence. Historian Paul Avrich

records Spies as saying "[t]here seems to prevail the opinion in some quarters that this meeting has been called for the purpose of inaugurating a riot, hence these warlike preparations on the part of so-called 'law and order.' However, let me tell you at the beginning that this meeting has not been called for any such purpose. The object of this meeting is to explain the general situation of the eight-hour movement and to throw light upon various incidents in connection with it."

The crowd was so calm that Mayor Carter Harrison, Sr.

, who had stopped by to watch, walked home early. Samuel Fielden

, the last speaker, was finishing his speech at about 10:30 when police ordered the rally to disperse and began marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon. A pipe bomb

was thrown at the police line and exploded, killing policeman Mathias J. Degan. The police immediately opened fire. Some workers were armed, but accounts vary widely as to how many shot back. The incident lasted less than five minutes.

Aside from Degan, several police officers appear to have been injured by the bomb, but most of the police casualties were caused by bullets, largely from friendly fire

. In his report on the incident, John Bonfield wrote that he "gave the order to cease firing, fearing that some of our men, in the darkness might fire into each other". An anonymous police official told the Chicago Tribune

, "A very large number of the police were wounded by each other's revolvers. ... It was every man for himself, and while some got two or three squares away, the rest emptied their revolvers, mainly into each other."

About 60 officers were wounded in the incident, along with an unknown number of civilians. In all, eight policemen and at least four workers were killed, including one policeman who died more than two years after the incident from injuries received that day. It is unclear how many civilians were wounded since many were afraid to seek medical attention, fearing arrest. Police captain Michael Schaack wrote the number of wounded workers was "largely in excess of that on the side of the police". The Chicago Herald described a scene of "wild carnage" and estimated at least fifty dead or wounded civilians lay in the streets.

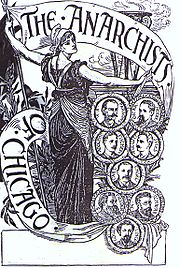

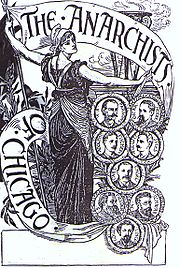

Eight people connected directly or indirectly with the rally and its anarchist organizers were arrested afterward and charged with Degan's murder: August Spies

Eight people connected directly or indirectly with the rally and its anarchist organizers were arrested afterward and charged with Degan's murder: August Spies

, Albert Parsons

, Adolph Fischer

, George Engel

, Louis Lingg

, Michael Schwab

, Samuel Fielden

and Oscar Neebe

. Five (Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg and Schwab) were German

immigrants and a sixth, Neebe, was a U.S. citizen of German descent. The other men, Parsons and Fielden, were born in the U.S. and England, respectively. Two other individuals, William Seliger and Rudolph Schnaubelt, were indicted, but never brought to trial. Seliger turned state's evidence and testified for the prosecution, and Schnaubelt fled the country before he could be brought to trial.

The trial started on June 21 and was presided over by Judge Joseph Gary

. The defense counsel included Sigmund Zeisler

, William Perkins Black

, William Foster, and Moses Salomon. The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, did not offer credible evidence

connecting the defendants with the bombing but argued that the person who had thrown the bomb was not discouraged to do so by the defendants, who as conspirators were therefore equally responsible. Albert Parsons' brother claimed there was evidence linking the Pinkertons

to the bomb.

The jury returned guilty verdicts for all eight defendants death sentences for seven of the men, and a sentence of 15 years in prison for Neebe. The sentencing sparked outrage from budding labor and workers' movements, resulted in protests around the world, and elevated the defendants as international political celebrities and heroes within labor and radical political circles. Meanwhile the press published often sensationalized accounts and opinions about the Haymarket affair, which polarized public reaction. In an article titled "Anarchy’s Red Hand", The New York Times

described the incident as the "bloody fruit" of "the villainous teachings of the Anarchists." The Chicago Times described the defendants as "arch counselors of riot, pillage, incendiarism and murder"; other reporters described them as "bloody brutes", "red ruffians", "dynamarchists", "bloody monsters", "cowards", "cutthroats", "thieves", "assassins", and "fiends". The journalist

George Frederic Parsons wrote a piece for The Atlantic Monthly

in which he identified the fears of middle-class Americans concerning labor radicalism, and asserted that the workers had only themselves to blame for their troubles. Edward Aveling

, Karl Marx

's son-in-law, remarked, "If these men are ultimately hanged, it will be the Chicago Tribune that has done it."

The case was appealed in 1887 to the Supreme Court of Illinois

, then to the United States Supreme Court

where the defendants were represented by John Randolph Tucker

, Roger Atkinson Pryor

, General Benjamin F. Butler

and William P. Black

. The petition for certiorari

was denied.

After the appeals had been exhausted, Illinois Governor Richard James Oglesby

After the appeals had been exhausted, Illinois Governor Richard James Oglesby

commuted Fielden's and Schwab's sentences to life in prison on November 10, 1887. On the eve of his scheduled execution, Lingg committed suicide in his cell with a smuggled dynamite cap which he reportedly held in his mouth like a cigar (the blast blew off half his face and he survived in agony for six hours).

The next day (November 11, 1887) Spies, Parsons, Fischer and Engel were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the Marseillaise

, then the anthem of the international revolutionary movement. Family members including Lucy Parsons

, who attempted to see them for the last time, were arrested and searched for bombs (none were found). According to witnesses, in the moments before the men were hanged, Spies shouted, "The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!" Witnesses reported that the condemned men did not die immediately when they dropped, but strangled to death slowly, a sight which left the spectators visibly shaken.

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the German Waldheim Cemetery

(later merged with Forest Home Cemetery) in Forest Park, Illinois

, a suburb of Chicago. Schwab and Neebe were also buried at Waldheim when they died, reuniting the "Martyrs." In 1893, the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument by sculptor Albert Weinert

was raised at Waldheim. Over a century later, it was designated a National Historic Landmark

by the United States Department of the Interior

, the only cemetery memorial to be noted as such.

The trial has been characterized as one of the most serious miscarriages of justice

in United States history. Most working people believed Pinkerton agents had provoked the incident. On June 26, 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld

signed pardons for Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab after having concluded all eight defendants were innocent. The governor said the reason for the bombing was the city of Chicago's failure to hold Pinkerton guards responsible for shooting workers. The pardons ended his political career.

The police commander who ordered the dispersal was later convicted of police corruption

. The bomb thrower was never identified.

(AFL) in 1888, the union decided to campaign for the shorter workday again. May 1, 1890, was agreed upon as the date on which workers would strike for an eight-hour work day.

In 1889, AFL president Samuel Gompers

In 1889, AFL president Samuel Gompers

wrote to the first congress of the Second International

, which was meeting in Paris

. He informed the world's socialists of the AFL's plans and proposed an international fight for a universal eight-hour work day. In response to Gompers's letter, the Second International adopted a resolution calling for "a great international demonstration" on a single date so workers everywhere could demand the eight-hour work day. In light of the Americans' plan, the International adopted May 1, 1890 as the date for this demonstration.

A secondary purpose behind the adoption of the resolution by the Second International was to honor the memory of the Haymarket martyrs and other workers who had been killed in association with the strikes on May 1, 1886. Historian Philip Foner

writes "[t]here is little doubt that everyone associated with the resolution passed by the Paris Congress knew of the May 1st demonstrations and strikes for the eight-hour day in 1886 in the United States ... and the events associated with the Haymarket tragedy."

The first international May Day was a spectacular success. The front page of the New York World

on May 2, 1890, was devoted to coverage of the event. Two of its headlines were "Parade of Jubilant Workingmen in All the Trade Centers of the Civilized World" and "Everywhere the Workmen Join in Demands for a Normal Day." The Times

of London listed two dozen European cities in which demonstrations had taken place, noting there had been rallies in Cuba, Peru and Chile. Commemoration of May Day became an annual event the following year.

The association of May Day with the Haymarket martyrs has remained strong in Mexico

. Mary Harris "Mother" Jones was in Mexico on May 1, 1921, and wrote of the "day of 'fiestas'" that marked "the killing of the workers in Chicago for demanding the eight-hour day". In 1929 The New York Times

referred to the May Day parade in Mexico City

as "the annual demonstration glorifying the memory of those who were killed in Chicago in 1886." The New York Times described the 1936 demonstration as a commemoration of "the death of the martyrs in Chicago." In 1939 Oscar Neebe's grandson attended the May Day parade in Mexico City and was shown, as his host told him, "how the world shows respect to your grandfather". An American visitor in 1981 wrote that she was embarrassed to explain to knowledgeable Mexican workers that American workers were ignorant of the Haymarket affair and the origins of May Day.

The influence of the Haymarket affair was not limited to the celebration of May Day. Emma Goldman

was attracted to anarchism after reading about the incident and the executions, which she later described as "the events that had inspired my spiritual birth and growth." She considered the Haymarket martyrs to be "the most decisive influence in my existence". Alexander Berkman

also described the Haymarket anarchists as "a potent and vital inspiration." Others whose commitment to anarchism crystallized as a result of the Haymarket affair included Voltairine de Cleyre and "Big Bill" Haywood

, a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World

. Goldman wrote to Max Nettlau

that the Haymarket affair had awakened the social consciousness of "hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people".

Several activists, including Dyer Lum

, Voltairine de Cleyre

and Robert Reitzel, later hinted they knew who the bomber was. Writers and other commentators have speculated about many possible suspects:

. The statue was unveiled on May 30, 1889, by Frank Degan, the son of Officer Mathias Degan. On May 4, 1927, the 41st anniversary of the Haymarket affair, a streetcar

jumped its tracks and crashed into the monument. The motorman said he was "sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised". The city restored the statue in 1928 and moved it to Union Park. During the 1950s, construction of the Kennedy Expressway

erased about half of the old, run-down market square, and in 1956, the statue was moved to a special platform built for it overlooking the freeway, near its original location.

The Haymarket statue was vandalized with black paint on May 4, 1968, the 82nd anniversary of the Haymarket affair, following a confrontation between police and demonstrators at a protest against the Vietnam War

. On October 6, 1969, shortly before the "Days of Rage

" protests, the statue was destroyed when a bomb was placed between its legs. Weatherman

took credit for the blast, which broke nearly 100 windows in the neighborhood and scattered pieces of the statue onto the Kennedy Expressway below. The statue was rebuilt and unveiled on May 4, 1970, then blown up again by Weathermen on October 6, 1970. The statue was again rebuilt, and Mayor Richard J. Daley

posted a 24-hour police guard at the statue. In 1972 it was moved to the lobby of the Central Police Headquarters, and in 1976 to the enclosed courtyard of the Chicago police academy. For another three decades the statue's empty, graffiti-marked pedestal stood on its platform in the run-down remains of Haymarket Square where it was known as an anarchist landmark. On June 1, 2007 the statue was rededicated at Chicago Police Headquarters with a new pedestal, unveiled by Geraldine Doceka, Officer Mathias Degan's great-granddaughter.

During the late 20th century, scholars doing research into the Haymarket affair were surprised to learn that much of the primary source documentation relating to the incident (beside materials concerning the trial) was not in Chicago, but had been transferred to then-communist

East Berlin

.

In 1992, the site of the speakers' wagon was marked by a bronze plaque set into the sidewalk, reading:

A decade of strife between labor and industry culminated here in a confrontation that resulted in the tragic death of both workers and policemen. On May 4, 1886, spectators at a labor rally had gathered around the mouth of Crane's Alley. A contingent of police approaching on Des Plaines Street were met by a bomb thrown from just south of the alley. The resultant trial of eight activists gained worldwide attention for the labor movement, and initiated the tradition of "May Day" labor rallies in many cities.

On September 14, 2004, Daley and union leaders—including the president of Chicago's police union—unveiled a monument by Chicago artist Mary Brogger, a fifteen-foot speakers' wagon sculpture echoing the wagon on which the labor leaders stood in Haymarket Square to champion the eight-hour day. The bronze sculpture, intended to be the centerpiece of a proposed "Labor Park", is meant to symbolize both the rally at Haymarket and free speech. The planned site was to include an international commemoration wall, sidewalk plaques, a cultural pylon, a seating area, and banners, but as of 2007 construction had not yet begun.

The plaques on the monument read as follows:

SITE OF THE HAYMARKET TRAGEDY

On the evening of May 4th, 1886, a tragedy of international significance unfolded on this site in Chicago's Haymarket produce district. An outdoor meeting had been hastily organized by anarchist activists to protest the violent death of workers during a labor lockout the previous day in another area of the city. Spectators gathered in the street as speakers addressed political, social, and labor issues from atop a wagon that stood at the location of this monument. When approximately 175 policemen approached with an order to disperse the meeting, a dynamite bomb was thrown into their ranks.

The identity and affiliation of the person who threw the bomb have never been determined, but this anonymous act had many victims. From the blast and panic that followed, seven policemen and at least four civilian bystanders lost their lives, but victims of the incident were not limited to those who died as a result of the bombing. In the aftermath, the people who organized and spoke at the meeting, and others who held unpopular political viewpoints were arrested and unfairly tried, even though none could be tied to the bombing itself.

Meeting organizers George Engle and Adolph Fischer, along with speakers August Spies and Albert Parsons were put to death by hanging. Activist Louis Lingg died violently in jail prior to his scheduled execution. Meeting speaker Samuel Fielden, and activists Oscar Neebe and Michael Schwab were sentenced to prison, but later pardoned in 1893 by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, citing the injustices of their trial.

Over the years, the site of the Haymarket bombing has become a powerful symbol for a diverse cross-section of people, ideals and movements. Its significance touches on the issues of free speech, the right of public assembly, organized labor, the fight for the eight-hour work day, law enforcement, justice, anarchy, and the right of every human being to pursue an equitable and prosperous life. For all, it is a poignant lesson in the rewards and consequences in such human pursuits.

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

. It began as a rally in support of striking

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

workers. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb

Bomb

A bomb is any of a range of explosive weapons that only rely on the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy...

at police

Chicago Police Department

The Chicago Police Department, also known as the CPD, is the principal law enforcement agency of Chicago, Illinois, in the United States, under the jurisdiction of the Mayor of Chicago. It is the largest police department in the Midwest and the second largest local law enforcement agency in the...

as they dispersed the public meeting. The bomb blast and ensuing gunfire

Shooting

Shooting is the act or process of firing rifles, shotguns or other projectile weapons such as bows or crossbows. Even the firing of artillery, rockets and missiles can be called shooting. A person who specializes in shooting is a marksman...

resulted in the deaths of eight police officers, mostly from friendly fire

Friendly fire

Friendly fire is inadvertent firing towards one's own or otherwise friendly forces while attempting to engage enemy forces, particularly where this results in injury or death. A death resulting from a negligent discharge is not considered friendly fire...

, and an unknown number of civilians. In the internationally publicized legal proceedings that followed, eight anarchists

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

were tried for murder. Five men were convicted, of whom four were executed and one committed suicide

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair or attributed to some underlying mental disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or drug abuse...

in prison, although the prosecution conceded none of the defendants had thrown the bomb.

The Haymarket affair is generally considered significant for the origin of international May Day

May Day

May Day on May 1 is an ancient northern hemisphere spring festival and usually a public holiday; it is also a traditional spring holiday in many cultures....

observances for workers. In popular literature, this event inspired the caricature of "a bomb-throwing anarchist." The causes of the incident are still controversial. The deeply polarized attitudes separating business and working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

people in late 19th-century Chicago are generally acknowledged as having precipitated the tragedy and its aftermath. The site of the incident was designated a Chicago Landmark

Chicago Landmark

Chicago Landmark is a designation of the Mayor of Chicago and the Chicago City Council for historic buildings and other sites in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Listed sites are selected after meeting a combination of criteria, including historical, economic, architectural, artistic, cultural,...

on March 25, 1992. The Haymarket Martyrs' Monument in nearby Forest Park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation...

and designated a National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

on February 18, 1997.

May Day parade and strikes

In October 1884, a convention held by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor UnionsFederation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada was a federation of labor unions created on November 15, 1881, in Pittsburgh...

unanimously set May 1, 1886, as the date by which the eight-hour work day

Eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement or 40-hour week movement, also known as the short-time movement, had its origins in the Industrial Revolution in Britain, where industrial production in large factories transformed working life and imposed long hours and poor working conditions. With working conditions...

would become standard. As the chosen date approached, U.S. labor unions prepared for a general strike

General strike

A general strike is a strike action by a critical mass of the labour force in a city, region, or country. While a general strike can be for political goals, economic goals, or both, it tends to gain its momentum from the ideological or class sympathies of the participants...

in support of the eight-hour day.

On Saturday, May 1, rallies were held throughout the United States. There were an estimated 10,000 demonstrators in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

and 11,000 in Detroit. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee is the largest city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin, the 28th most populous city in the United States and 39th most populous region in the United States. It is the county seat of Milwaukee County and is located on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan. According to 2010 census data, the...

, some 10,000 workers turned out. The movement's center was in Chicago, where an estimated 40,000 workers went on strike. Albert Parsons

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons was a pioneer American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist...

was an anarchist

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

and founder of the International Working People's Association

International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association , sometimes known as the "Black International," was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a convention held in London, England...

(IWPA). Parsons, with his wife Lucy

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was an American labor organizer and radical socialist. She is remembered as a powerful orator.-Life:...

and their children, led a march of 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue

Michigan Avenue (Chicago)

Michigan Avenue is a major north-south street in Chicago which runs at 100 east south of the Chicago River and at 132 East north of the river from 12628 south to 950 north in the Chicago street address system...

. Another 10,000 men employed in the lumber yards held a separate march in Chicago. Estimates of the number of striking workers across the U.S. range from 300,000 to half a million.

On May 3, striking workers in Chicago met near the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company plant. Union molders at the plant had been locked out

Lockout (industry)

A lockout is a work stoppage in which an employer prevents employees from working. This is different from a strike, in which employees refuse to work.- Causes :...

since early February and the predominantly Irish-American workers at McCormick had come under attack from Pinkerton

Pinkerton National Detective Agency

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, usually shortened to the Pinkertons, is a private U.S. security guard and detective agency established by Allan Pinkerton in 1850. Pinkerton became famous when he claimed to have foiled a plot to assassinate president-elect Abraham Lincoln, who later hired...

guards during an earlier strike action in 1885. This event, along with the eight-hour militancy of McCormick workers, had gained the strikers some respect and notoriety around the city. By the time of the 1886 general strike, strikebreaker

Strikebreaker

A strikebreaker is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who are not employed by the company prior to the trade union dispute, but rather hired prior to or during the strike to keep the organisation running...

s entering the McCormick plant were under protection from a garrison of 400 police officers. Although half of the replacement workers defected to the general strike on May 1, McCormick workers continued to harass strikebreaker

Strikebreaker

A strikebreaker is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who are not employed by the company prior to the trade union dispute, but rather hired prior to or during the strike to keep the organisation running...

s as they crossed the picket lines.

Speaking to a rally outside the plant on May 3, August Spies

August Spies

August Vincent Theodore Spies was an anarchist labor activist who was found guilty of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police at the Haymarket affair.-Background:...

advised the striking workers to "hold together, to stand by their union, or they would not succeed." Well-planned and coordinated, the general strike to this point had remained largely nonviolent. When the end-of-the-workday bell sounded, however, a group of workers surged to the gates to confront the strikebreakers. Despite calls by Spies for the workers to remain calm, gunfire erupted as police fired on the crowd. In the end, two McCormick workers were killed (although some newspaper accounts said there were six fatalities). Spies would later testify, "I was very indignant. I knew from experience of the past that this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement."

Outraged by this act of police violence, local anarchists quickly printed and distributed fliers calling for a rally the following day at Haymarket Square (also called the Haymarket), which was then a bustling commercial center near the corner of Randolph Street and Desplaines Street. Printed in German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

and English, the fliers alleged police had murdered the strikers on behalf of business interests and urged workers to seek justice. The first batch of fliers contain the words Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force! When Spies saw the line, he said he would not speak at the rally unless the words were removed from the flier. All but a few hundred of the fliers were destroyed, and new fliers were printed without the offending words. More than 20,000 copies of the revised flier were distributed.

Rally at Haymarket Square

August Spies

August Vincent Theodore Spies was an anarchist labor activist who was found guilty of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police at the Haymarket affair.-Background:...

spoke to the large crowd while standing in an open wagon on Des Plaines Street while a large number of on-duty police officers watched from nearby. According to witnesses, Spies began by saying the rally was not meant to incite violence. Historian Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich was a professor and historian. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for most of his life and was vital in preserving the history of the anarchist movement in Russia and the United States....

records Spies as saying "[t]here seems to prevail the opinion in some quarters that this meeting has been called for the purpose of inaugurating a riot, hence these warlike preparations on the part of so-called 'law and order.' However, let me tell you at the beginning that this meeting has not been called for any such purpose. The object of this meeting is to explain the general situation of the eight-hour movement and to throw light upon various incidents in connection with it."

The crowd was so calm that Mayor Carter Harrison, Sr.

Carter Harrison, Sr.

Carter Henry Harrison, Sr. was an American politician who served as mayor of Chicago, Illinois from 1879 until 1887; he was subsequently elected to a fifth term in 1893 but was assassinated before completing his term. He previously served two terms in the United States House of Representatives...

, who had stopped by to watch, walked home early. Samuel Fielden

Samuel Fielden

Samuel Fielden was a socialist, anarchist and labor activist who was one of eight convicted in the 1886 Haymarket bombing.-Early life:...

, the last speaker, was finishing his speech at about 10:30 when police ordered the rally to disperse and began marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon. A pipe bomb

Pipe bomb

A pipe bomb is an improvised explosive device, a tightly sealed section of pipe filled with an explosive material. The containment provided by the pipe means that simple low explosives can be used to produce a relatively large explosion, and the fragmentation of the pipe itself creates potentially...

was thrown at the police line and exploded, killing policeman Mathias J. Degan. The police immediately opened fire. Some workers were armed, but accounts vary widely as to how many shot back. The incident lasted less than five minutes.

Aside from Degan, several police officers appear to have been injured by the bomb, but most of the police casualties were caused by bullets, largely from friendly fire

Friendly fire

Friendly fire is inadvertent firing towards one's own or otherwise friendly forces while attempting to engage enemy forces, particularly where this results in injury or death. A death resulting from a negligent discharge is not considered friendly fire...

. In his report on the incident, John Bonfield wrote that he "gave the order to cease firing, fearing that some of our men, in the darkness might fire into each other". An anonymous police official told the Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune

The Chicago Tribune is a major daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, and the flagship publication of the Tribune Company. Formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" , it remains the most read daily newspaper of the Chicago metropolitan area and the Great Lakes region and is...

, "A very large number of the police were wounded by each other's revolvers. ... It was every man for himself, and while some got two or three squares away, the rest emptied their revolvers, mainly into each other."

About 60 officers were wounded in the incident, along with an unknown number of civilians. In all, eight policemen and at least four workers were killed, including one policeman who died more than two years after the incident from injuries received that day. It is unclear how many civilians were wounded since many were afraid to seek medical attention, fearing arrest. Police captain Michael Schaack wrote the number of wounded workers was "largely in excess of that on the side of the police". The Chicago Herald described a scene of "wild carnage" and estimated at least fifty dead or wounded civilians lay in the streets.

Trial, executions, and pardons

August Spies

August Vincent Theodore Spies was an anarchist labor activist who was found guilty of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police at the Haymarket affair.-Background:...

, Albert Parsons

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons was a pioneer American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist...

, Adolph Fischer

Adolph Fischer

Adolph Fischer was an anarchist and labor union activist tried and executed after the Haymarket Riot.-Early life:...

, George Engel

George Engel

George Engel was an anarchist and labor union activist executed after the Haymarket riot, along with Albert Parsons, August Spies, and Adolph Fischer.-Early life:...

, Louis Lingg

Louis Lingg

Louis Lingg was a German anarchist who committed suicide while in jail, after being arrested as an agitator during the Haymarket Square bombing.-Birth:...

, Michael Schwab

Michael Schwab

Michael Schwab was a German-American labor organizer and one of the defendants in the Haymarket Square incident.-Early years:...

, Samuel Fielden

Samuel Fielden

Samuel Fielden was a socialist, anarchist and labor activist who was one of eight convicted in the 1886 Haymarket bombing.-Early life:...

and Oscar Neebe

Oscar Neebe

Oscar William Neebe I was an anarchist, labor activist and one of the defendants in the Haymarket bombing trial.-Early life:...

. Five (Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg and Schwab) were German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

immigrants and a sixth, Neebe, was a U.S. citizen of German descent. The other men, Parsons and Fielden, were born in the U.S. and England, respectively. Two other individuals, William Seliger and Rudolph Schnaubelt, were indicted, but never brought to trial. Seliger turned state's evidence and testified for the prosecution, and Schnaubelt fled the country before he could be brought to trial.

The trial started on June 21 and was presided over by Judge Joseph Gary

Joseph Gary

Joseph E. Gary was judge who presided over the trial of eight anarchists tried for their alleged role in the Haymarket Riot. Born in Potsdam, New York, USA, he worked as a carpenter, then moved to St. Louis in 1843 to study law. He was admitted to the bar in 1844 and practiced for five years in...

. The defense counsel included Sigmund Zeisler

Sigmund Zeisler

Sigmund Zeisler was a German-Jewish U.S. attorney born in Austria and known for his defense of radicals in Chicago in the 1880s. His wife was the famed concert pianist Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler.-Childhood, marriage and legal education:...

, William Perkins Black

William P. Black

William Perkins Black was a lawyer and veteran of the American Civil War. He received America's highest military decoration - the Medal of Honor - for his actions at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in 1862.-Biography:...

, William Foster, and Moses Salomon. The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, did not offer credible evidence

Evidence (law)

The law of evidence encompasses the rules and legal principles that govern the proof of facts in a legal proceeding. These rules determine what evidence can be considered by the trier of fact in reaching its decision and, sometimes, the weight that may be given to that evidence...

connecting the defendants with the bombing but argued that the person who had thrown the bomb was not discouraged to do so by the defendants, who as conspirators were therefore equally responsible. Albert Parsons' brother claimed there was evidence linking the Pinkertons

Pinkerton National Detective Agency

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, usually shortened to the Pinkertons, is a private U.S. security guard and detective agency established by Allan Pinkerton in 1850. Pinkerton became famous when he claimed to have foiled a plot to assassinate president-elect Abraham Lincoln, who later hired...

to the bomb.

The jury returned guilty verdicts for all eight defendants death sentences for seven of the men, and a sentence of 15 years in prison for Neebe. The sentencing sparked outrage from budding labor and workers' movements, resulted in protests around the world, and elevated the defendants as international political celebrities and heroes within labor and radical political circles. Meanwhile the press published often sensationalized accounts and opinions about the Haymarket affair, which polarized public reaction. In an article titled "Anarchy’s Red Hand", The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

described the incident as the "bloody fruit" of "the villainous teachings of the Anarchists." The Chicago Times described the defendants as "arch counselors of riot, pillage, incendiarism and murder"; other reporters described them as "bloody brutes", "red ruffians", "dynamarchists", "bloody monsters", "cowards", "cutthroats", "thieves", "assassins", and "fiends". The journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

George Frederic Parsons wrote a piece for The Atlantic Monthly

The Atlantic Monthly

The Atlantic is an American magazine founded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1857. It was created as a literary and cultural commentary magazine. It quickly achieved a national reputation, which it held for more than a century. It was important for recognizing and publishing new writers and poets,...

in which he identified the fears of middle-class Americans concerning labor radicalism, and asserted that the workers had only themselves to blame for their troubles. Edward Aveling

Edward Aveling

Edward Bibbins Aveling was a prominent English biology instructor and popular spokesman for Darwinian evolution and atheism. He later met and moved in with Eleanor Marx, the youngest daughter of Karl Marx and became a socialist activist...

, Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

's son-in-law, remarked, "If these men are ultimately hanged, it will be the Chicago Tribune that has done it."

The case was appealed in 1887 to the Supreme Court of Illinois

Supreme Court of Illinois

The Supreme Court of Illinois is the state supreme court of Illinois. The court's authority is granted in Article VI of the current Illinois Constitution, which provides for seven justices elected from the five appellate judicial districts of the state: Three justices from the First District and...

, then to the United States Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

where the defendants were represented by John Randolph Tucker

John Randolph Tucker (1823-1897)

John Randolph Tucker was an American lawyer, author, and politician from Virginia. He was a member of the Tucker family, which was influential in the legal and political affairs of the state of Virginia and the United States for many years.-Early Life and Family:Tucker was born in Winchester,...

, Roger Atkinson Pryor

Roger Atkinson Pryor

Roger Atkinson Pryor was both an American politician and a Confederate politician serving as a congressman on both sides. He was also a jurist, serving in the New York Supreme Court, a lawyer, and newspaper editor...

, General Benjamin F. Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (politician)

Benjamin Franklin Butler was an American lawyer and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 33rd Governor of Massachusetts....

and William P. Black

William P. Black

William Perkins Black was a lawyer and veteran of the American Civil War. He received America's highest military decoration - the Medal of Honor - for his actions at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in 1862.-Biography:...

. The petition for certiorari

Certiorari

Certiorari is a type of writ seeking judicial review, recognized in U.S., Roman, English, Philippine, and other law. Certiorari is the present passive infinitive of the Latin certiorare...

was denied.

Richard James Oglesby

Richard James Oglesby was an Illinois statesman and U.S. Army officer. He served in the Mexican-American War and was a major general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He also served Illinois in the legislature. Near the end of the civil war, he was elected the 14th Governor of...

commuted Fielden's and Schwab's sentences to life in prison on November 10, 1887. On the eve of his scheduled execution, Lingg committed suicide in his cell with a smuggled dynamite cap which he reportedly held in his mouth like a cigar (the blast blew off half his face and he survived in agony for six hours).

The next day (November 11, 1887) Spies, Parsons, Fischer and Engel were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the Marseillaise

La Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. The song, originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin" was written and composed by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in 1792. The French National Convention adopted it as the Republic's anthem in 1795...

, then the anthem of the international revolutionary movement. Family members including Lucy Parsons

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was an American labor organizer and radical socialist. She is remembered as a powerful orator.-Life:...

, who attempted to see them for the last time, were arrested and searched for bombs (none were found). According to witnesses, in the moments before the men were hanged, Spies shouted, "The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!" Witnesses reported that the condemned men did not die immediately when they dropped, but strangled to death slowly, a sight which left the spectators visibly shaken.

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the German Waldheim Cemetery

German Waldheim Cemetery

German Waldheim Cemetery, also known as Waldheim Cemetery, was a cemetery in Forest Park, a suburb of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois. It was originally founded in 1873 as a non-religion specific cemetery, where Freemasons, Roma, and German-speaking immigrants to Chicago could be buried without...

(later merged with Forest Home Cemetery) in Forest Park, Illinois

Forest Park, Illinois

Forest Park is a village in Cook County, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago in the United States. The population was 15,688 at the 2000 census...

, a suburb of Chicago. Schwab and Neebe were also buried at Waldheim when they died, reuniting the "Martyrs." In 1893, the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument by sculptor Albert Weinert

Albert Weinert

Albert Weinert American sculptor Born in Leipzig, Germany, Weinert attended the Royal Academy there and then the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, Belgium. In 1886 he immigrated to the United States, settling first in San Francisco and then New York...

was raised at Waldheim. Over a century later, it was designated a National Historic Landmark

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation...

by the United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior is the United States federal executive department of the U.S. government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land and natural resources, and the administration of programs relating to Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native...

, the only cemetery memorial to be noted as such.

The trial has been characterized as one of the most serious miscarriages of justice

Miscarriage of justice

A miscarriage of justice primarily is the conviction and punishment of a person for a crime they did not commit. The term can also apply to errors in the other direction—"errors of impunity", and to civil cases. Most criminal justice systems have some means to overturn, or "quash", a wrongful...

in United States history. Most working people believed Pinkerton agents had provoked the incident. On June 26, 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld was the 20th Governor of the U.S. state of Illinois from 1893 until 1897. He was the first Democratic governor of that state since the 1850s...

signed pardons for Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab after having concluded all eight defendants were innocent. The governor said the reason for the bombing was the city of Chicago's failure to hold Pinkerton guards responsible for shooting workers. The pardons ended his political career.

The police commander who ordered the dispersal was later convicted of police corruption

Police corruption

Police corruption is a specific form of police misconduct designed to obtain financial benefits, other personal gain, or career advancement for a police officer or officers in exchange for not pursuing, or selectively pursuing, an investigation or arrest....

. The bomb thrower was never identified.

Effects on the labor movement and May Day

The Haymarket affair was a setback for American labor and its fight for the eight-hour day. At the convention of the American Federation of LaborAmerican Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor was one of the first federations of labor unions in the United States. It was founded in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions disaffected from the Knights of Labor, a national labor association. Samuel Gompers was elected president of the Federation at its...

(AFL) in 1888, the union decided to campaign for the shorter workday again. May 1, 1890, was agreed upon as the date on which workers would strike for an eight-hour work day.

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers was an English-born American cigar maker who became a labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor , and served as that organization's president from 1886 to 1894 and from 1895 until his death in 1924...

wrote to the first congress of the Second International

Second International

The Second International , the original Socialist International, was an organization of socialist and labour parties formed in Paris on July 14, 1889. At the Paris meeting delegations from 20 countries participated...

, which was meeting in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. He informed the world's socialists of the AFL's plans and proposed an international fight for a universal eight-hour work day. In response to Gompers's letter, the Second International adopted a resolution calling for "a great international demonstration" on a single date so workers everywhere could demand the eight-hour work day. In light of the Americans' plan, the International adopted May 1, 1890 as the date for this demonstration.

A secondary purpose behind the adoption of the resolution by the Second International was to honor the memory of the Haymarket martyrs and other workers who had been killed in association with the strikes on May 1, 1886. Historian Philip Foner

Philip Foner

Philip S. Foner was an American Marxist labor historian and teacher. The author and editor of more than 100 books, the prolific Foner wrote extensively on what were at the time academically unpopular themes, such as the role of radicals, blacks, and women in American history...

writes "[t]here is little doubt that everyone associated with the resolution passed by the Paris Congress knew of the May 1st demonstrations and strikes for the eight-hour day in 1886 in the United States ... and the events associated with the Haymarket tragedy."

The first international May Day was a spectacular success. The front page of the New York World

New York World

The New York World was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers...

on May 2, 1890, was devoted to coverage of the event. Two of its headlines were "Parade of Jubilant Workingmen in All the Trade Centers of the Civilized World" and "Everywhere the Workmen Join in Demands for a Normal Day." The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

of London listed two dozen European cities in which demonstrations had taken place, noting there had been rallies in Cuba, Peru and Chile. Commemoration of May Day became an annual event the following year.

The association of May Day with the Haymarket martyrs has remained strong in Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

. Mary Harris "Mother" Jones was in Mexico on May 1, 1921, and wrote of the "day of 'fiestas'" that marked "the killing of the workers in Chicago for demanding the eight-hour day". In 1929 The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

referred to the May Day parade in Mexico City

Mexico City

Mexico City is the Federal District , capital of Mexico and seat of the federal powers of the Mexican Union. It is a federal entity within Mexico which is not part of any one of the 31 Mexican states but belongs to the federation as a whole...

as "the annual demonstration glorifying the memory of those who were killed in Chicago in 1886." The New York Times described the 1936 demonstration as a commemoration of "the death of the martyrs in Chicago." In 1939 Oscar Neebe's grandson attended the May Day parade in Mexico City and was shown, as his host told him, "how the world shows respect to your grandfather". An American visitor in 1981 wrote that she was embarrassed to explain to knowledgeable Mexican workers that American workers were ignorant of the Haymarket affair and the origins of May Day.

The influence of the Haymarket affair was not limited to the celebration of May Day. Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century....

was attracted to anarchism after reading about the incident and the executions, which she later described as "the events that had inspired my spiritual birth and growth." She considered the Haymarket martyrs to be "the most decisive influence in my existence". Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman was an anarchist known for his political activism and writing. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century....

also described the Haymarket anarchists as "a potent and vital inspiration." Others whose commitment to anarchism crystallized as a result of the Haymarket affair included Voltairine de Cleyre and "Big Bill" Haywood

Bill Haywood

William Dudley Haywood , better known as "Big Bill" Haywood, was a founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World , and a member of the Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of America...

, a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World is an international union. At its peak in 1923, the organization claimed some 100,000 members in good standing, and could marshal the support of perhaps 300,000 workers. Its membership declined dramatically after a 1924 split brought on by internal conflict...

. Goldman wrote to Max Nettlau

Max Nettlau

Max Heinrich Hermann Reinhardt Nettlau was a German anarchist and historian. Although born in Neuwaldegg and raised in Vienna he retained his Prussian nationality throughout his life. A student of the Welsh language he spent time in London where he joined the Socialist League where he met...

that the Haymarket affair had awakened the social consciousness of "hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people".

Suspected bombers

While admitting none of the defendants was involved in the bombing, the prosecution made a weak argument that Lingg had built the bomb and two prosecution witnesses (Harry Gilmer and Malvern Thompson) tried to imply the bomb thrower was helped by Spies, Fischer and Schwab. The defendants claimed they had no knowledge of the bomber at all.Several activists, including Dyer Lum

Dyer Lum

Dyer Daniel Lum was a 19th-century American anarchist labor activist and poet. A leading anarcho-syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.Lum was a prolific writer who wrote a number of...

, Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre was an American anarchist writer and feminist. She was a prolific writer and speaker, opposing the state, marriage, and the domination of religion in sexuality and women's lives. She began her activist career in the freethought movement...

and Robert Reitzel, later hinted they knew who the bomber was. Writers and other commentators have speculated about many possible suspects:

- Rudolph Schnaubelt (1863–1901) was an activist and the brother-in law of Michael Schwab. He was at the Haymarket when the bomb exploded. Schnaubelt was indicted with the other defendants but fled the city and later the country before he could be brought to trial. The prosecution assumed he was the bomb thrower. State witness Gilmer claimed to have seen him throw the bomb, but Schnaubelt did not resemble Gilmer's description of the bomber. Schnaubelt later wrote two letters from London disclaiming all responsibility. He is the most generally accepted and widely known suspect mainly because of The Bomb, Frank HarrisFrank HarrisFrank Harris was a Irish-born, naturalized-American author, editor, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day...

's 1908 fictionalization of the tragedy. Written from Schnaubelt's point of view, the story opens with him confessing on his deathbed. However, Harris's description was fictional and those who knew Schnaubelt vehemently criticized the book. - George Schwab was a German shoemaker who died in 1924. German anarchist Carl Nold claimed he learned Schwab was the bomber through correspondence with other activists but no proof ever emerged. Historian Paul AvrichPaul AvrichPaul Avrich was a professor and historian. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for most of his life and was vital in preserving the history of the anarchist movement in Russia and the United States....

also suspected him but noted that while Schwab was in Chicago, he had only arrived days before. This contradicted statements by others that the bomber was a well-known figure in Chicago. - George Meng (b. around 1840) was a German anarchist and teamster who owned a small farm outside of Chicago where he had settled in 1883 after emigrating from BavariaBavariaBavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

. Like Parsons and Spies, he was a delegate at the Pittsburgh Congress and a member of the IWPA. Meng's granddaughter, Adah Maurer, wrote Paul Avrich a letter in which she said that her mother, who was 15 at the time of the bombing, told her that her father was the bomber. Meng died sometime before 1907 in a saloon fire. Based on his correspondence with Maurer, Avrich concluded that there was a "strong possibility" that the little-known Meng may have been the bomber. - An agent provocateurAgent provocateurTraditionally, an agent provocateur is a person employed by the police or other entity to act undercover to entice or provoke another person to commit an illegal act...

was suggested by some members of the anarchist movement. Albert Parsons believed the bomber was a member of the police or the Pinkertons trying to undermine the labor movement. However, this contradicts the statements of several activists who said the bomber was one of their own. Lucy Parsons and Johann MostJohann MostJohann Joseph Most was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed". His grandson was Boston Celtics radio play-by-play man Johnny Most...

rejected this notion. Dyer Lum said it was "puerile" to ascribe "the Haymarket bomb to a Pinkerton." - A disgruntled worker was widely suspected. When Adolph Fischer was asked if he knew who threw the bomb, he answered, "I suppose it was some excited workingman." Oscar Neebe said it was a "crank." Governor Altgeld speculated the bomb thrower might have been a disgruntled worker who was not associated with the defendants or the anarchist movement but had a personal grudge against the police. In his pardoning statement, Altgeld said the record of police brutality towards the workers had invited revenge adding, "Capt. Bonfield is the man who is really responsible for the deaths of the police officers."

- Klemana Schuetz was identified as the bomber by Franz Mayhoff, a New York anarchist and fraudster, who claimed in an affidavit that Schuetz had once admitted throwing the Haymarket bomb. August Wagener, Mayhoff's attorney, sent a telegram from New York to defense attorney Captain William Black the day before the executions claiming knowledge of the bomber's identity. Black tried to delay the execution with this telegram but Governor Oglesby refused. It was later learned that Schuetz was the primary witness against Mayhoff at his trial for insurance fraud, so Mayhoff's affidavit has never been regarded as credible by historians.

- Thomas Owen was a carpenter from PennsylvaniaPennsylvaniaThe Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

. Severely injured in an accident a week before the executions, Owen reportedly confessed to the bombing on his deathbed by saying, "I was at the Haymarket riot and am an anarchist and say that I threw a bomb in that riot." He was an anarchist and apparently had been in Chicago at the time but other accounts note that long before his accident he had said he was at the Haymarket and saw the bomb thrower. Owen may have been trying to save the condemned men. - Reinold "Big" Krueger was killed by police either in the melee after the bombing or in a separate disturbance the next day and has been named as a suspect but there is no supporting evidence.

- A mysterious outsider was reported by John Philip Deluse, a saloon keeper in IndianapolisIndianapolisIndianapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Indiana, and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population is 839,489. It is by far Indiana's largest city and, as of the 2010 U.S...

who claimed he encountered a stranger in his saloon the day before the bombing. The man was carrying a satchel and on his way from New York to Chicago. According to Deluse, the stranger was interested in the labor situation in Chicago, repeatedly pointed to his satchel and said, "You will hear of some trouble there very soon." Parsons used Deluse's testimony to suggest the bomb thrower was sent by eastern capitalists. Nothing more was ever learned about Deluse's claim.

Haymarket Square in the aftermath

In 1889, a commemorative nine-foot (2.7 meter) bronze statue of a Chicago policeman by sculptor Johannes Gelert was erected in the middle of Haymarket Square with private funds raised by the Union League Club of ChicagoUnion League Club of Chicago

The Union League Club of Chicago is a prominent social club located in downtown Chicago.-History:The Club can trace its roots to 1862, when radical southern sympathizers in the north were plotting an insurrection in Lincoln’s home state...

. The statue was unveiled on May 30, 1889, by Frank Degan, the son of Officer Mathias Degan. On May 4, 1927, the 41st anniversary of the Haymarket affair, a streetcar

Tram

A tram is a passenger rail vehicle which runs on tracks along public urban streets and also sometimes on separate rights of way. It may also run between cities and/or towns , and/or partially grade separated even in the cities...

jumped its tracks and crashed into the monument. The motorman said he was "sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised". The city restored the statue in 1928 and moved it to Union Park. During the 1950s, construction of the Kennedy Expressway

Kennedy Expressway

The John F. Kennedy Expressway is a long highway that travels northwest from the Chicago Loop to O'Hare International Airport. The expressway is named for the 35th U.S. President, John F. Kennedy. The Interstate 90 portion of the Kennedy is a part of the much longer I-90...

erased about half of the old, run-down market square, and in 1956, the statue was moved to a special platform built for it overlooking the freeway, near its original location.

The Haymarket statue was vandalized with black paint on May 4, 1968, the 82nd anniversary of the Haymarket affair, following a confrontation between police and demonstrators at a protest against the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

. On October 6, 1969, shortly before the "Days of Rage

Days of Rage

The Days of Rage demonstrations were a series of direct actions taken over a course of three days in October 1969 in Chicago organized by the Weatherman faction of the Students for a Democratic Society...

" protests, the statue was destroyed when a bomb was placed between its legs. Weatherman

Weatherman (organization)

Weatherman, known colloquially as the Weathermen and later the Weather Underground Organization , was an American radical left organization. It originated in 1969 as a faction of Students for a Democratic Society composed for the most part of the national office leadership of SDS and their...

took credit for the blast, which broke nearly 100 windows in the neighborhood and scattered pieces of the statue onto the Kennedy Expressway below. The statue was rebuilt and unveiled on May 4, 1970, then blown up again by Weathermen on October 6, 1970. The statue was again rebuilt, and Mayor Richard J. Daley

Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley served for 21 years as the mayor and undisputed Democratic boss of Chicago and is considered by historians to be the "last of the big city bosses." He played a major role in the history of the Democratic Party, especially with his support of John F...

posted a 24-hour police guard at the statue. In 1972 it was moved to the lobby of the Central Police Headquarters, and in 1976 to the enclosed courtyard of the Chicago police academy. For another three decades the statue's empty, graffiti-marked pedestal stood on its platform in the run-down remains of Haymarket Square where it was known as an anarchist landmark. On June 1, 2007 the statue was rededicated at Chicago Police Headquarters with a new pedestal, unveiled by Geraldine Doceka, Officer Mathias Degan's great-granddaughter.

During the late 20th century, scholars doing research into the Haymarket affair were surprised to learn that much of the primary source documentation relating to the incident (beside materials concerning the trial) was not in Chicago, but had been transferred to then-communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

East Berlin

East Berlin

East Berlin was the name given to the eastern part of Berlin between 1949 and 1990. It consisted of the Soviet sector of Berlin that was established in 1945. The American, British and French sectors became West Berlin, a part strongly associated with West Germany but a free city...

.

In 1992, the site of the speakers' wagon was marked by a bronze plaque set into the sidewalk, reading:

A decade of strife between labor and industry culminated here in a confrontation that resulted in the tragic death of both workers and policemen. On May 4, 1886, spectators at a labor rally had gathered around the mouth of Crane's Alley. A contingent of police approaching on Des Plaines Street were met by a bomb thrown from just south of the alley. The resultant trial of eight activists gained worldwide attention for the labor movement, and initiated the tradition of "May Day" labor rallies in many cities.

- Designated on March 25, 1992

- Richard M. DaleyRichard M. DaleyRichard Michael Daley is a United States politician, member of the national and local Democratic Party, and former Mayor of Chicago, Illinois. He was elected mayor in 1989 and reelected in 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, and 2007. He was the longest serving Chicago mayor, surpassing the tenure of his...

, Mayor

On September 14, 2004, Daley and union leaders—including the president of Chicago's police union—unveiled a monument by Chicago artist Mary Brogger, a fifteen-foot speakers' wagon sculpture echoing the wagon on which the labor leaders stood in Haymarket Square to champion the eight-hour day. The bronze sculpture, intended to be the centerpiece of a proposed "Labor Park", is meant to symbolize both the rally at Haymarket and free speech. The planned site was to include an international commemoration wall, sidewalk plaques, a cultural pylon, a seating area, and banners, but as of 2007 construction had not yet begun.

The plaques on the monument read as follows:

SITE OF THE HAYMARKET TRAGEDY

On the evening of May 4th, 1886, a tragedy of international significance unfolded on this site in Chicago's Haymarket produce district. An outdoor meeting had been hastily organized by anarchist activists to protest the violent death of workers during a labor lockout the previous day in another area of the city. Spectators gathered in the street as speakers addressed political, social, and labor issues from atop a wagon that stood at the location of this monument. When approximately 175 policemen approached with an order to disperse the meeting, a dynamite bomb was thrown into their ranks.

The identity and affiliation of the person who threw the bomb have never been determined, but this anonymous act had many victims. From the blast and panic that followed, seven policemen and at least four civilian bystanders lost their lives, but victims of the incident were not limited to those who died as a result of the bombing. In the aftermath, the people who organized and spoke at the meeting, and others who held unpopular political viewpoints were arrested and unfairly tried, even though none could be tied to the bombing itself.

Meeting organizers George Engle and Adolph Fischer, along with speakers August Spies and Albert Parsons were put to death by hanging. Activist Louis Lingg died violently in jail prior to his scheduled execution. Meeting speaker Samuel Fielden, and activists Oscar Neebe and Michael Schwab were sentenced to prison, but later pardoned in 1893 by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, citing the injustices of their trial.

Over the years, the site of the Haymarket bombing has become a powerful symbol for a diverse cross-section of people, ideals and movements. Its significance touches on the issues of free speech, the right of public assembly, organized labor, the fight for the eight-hour work day, law enforcement, justice, anarchy, and the right of every human being to pursue an equitable and prosperous life. For all, it is a poignant lesson in the rewards and consequences in such human pursuits.

Gallery

See also

- Bay View Massacre (in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, May 5, 1886)

- Days of RageDays of RageThe Days of Rage demonstrations were a series of direct actions taken over a course of three days in October 1969 in Chicago organized by the Weatherman faction of the Students for a Democratic Society...

- Dyer LumDyer LumDyer Daniel Lum was a 19th-century American anarchist labor activist and poet. A leading anarcho-syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.Lum was a prolific writer who wrote a number of...

, close associate of the defendants who wrote an account of the case in 1891. - First Red ScareFirst Red ScareIn American history, the First Red Scare of 1919–1920 was marked by a widespread fear of Bolshevism and anarchism. Concerns over the effects of radical political agitation in American society and alleged spread in the American labor movement fueled the paranoia that defined the period.The First Red...

of 1917-1920 - May Day Riots of 1894May Day Riots of 1894The May Day Riots of 1894 were a series of violent demonstrations that occurred throughout Cleveland, Ohio on May 1 , 1894 . Cleveland's unemployment rate increased dramatically during the Panic of 1893...

- May Day Riots of 1919May Day Riots of 1919The May Day Riots of 1919 were a series of violent demonstrations that occurred throughout Cleveland, Ohio on May 1 , 1919. The riots began when Socialist leader, Charles Ruthenberg organized a May Day parade of local trade unionists, socialists, communists, and anarchists to protest the jailing...