Georges Boulanger

Encyclopedia

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

general

General

A general officer is an officer of high military rank, usually in the army, and in some nations, the air force. The term is widely used by many nations of the world, and when a country uses a different term, there is an equivalent title given....

and reactionary

Reactionary

The term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

. At the apogee of his popularity in January 1889 many republicans including Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

feared the threat of a coup d'état by Boulanger and the establishment of a dictatorship.

Early life and career

Born in RennesRennes

Rennes is a city in the east of Brittany in northwestern France. Rennes is the capital of the region of Brittany, as well as the Ille-et-Vilaine department.-History:...

, Boulanger graduated from Saint-Cyr

École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr

The École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr is the foremost French military academy. Its official name is . It is often referred to as Saint-Cyr . Its motto is "Ils s'instruisent pour vaincre": literally "They study to vanquish" or "Training for victory"...

and entered regular service in the French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

in 1856. He fought in the Austro-Sardinian War (he was wounded at Robecchetto, where he received the Légion d'honneur

Légion d'honneur

The Legion of Honour, or in full the National Order of the Legion of Honour is a French order established by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Consulat which succeeded to the First Republic, on 19 May 1802...

), and in the occupation of Cochin China, after which he became a captain and instructor

Drill instructor

A drill instructor is a non-commissioned officer or Staff Non-Commissioned Officer in the armed forces or police forces with specific duties that vary by country. In the U.S. armed forces, they are assigned the duty of indoctrinating new recruits entering the military into the customs and...

at Saint-Cyr. During the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

, Georges Boulanger was noted for his bravery, and soon promoted to chef de bataillon

Major

Major is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

; he was again wounded while fighting at Champigny-sur-Marne

Champigny-sur-Marne

Champigny-sur-Marne is a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris.-Name:Champigny-sur-Marne was originally called simply Champigny...

(during the Siege of Paris

Siege of Paris

The Siege of Paris, lasting from September 19, 1870 – January 28, 1871, and the consequent capture of the city by Prussian forces led to French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of the German Empire as well as the Paris Commune....

). Subsequently, Boulanger was among the Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

military leaders who crushed the Paris Commune

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that briefly ruled Paris from March 18 to May 28, 1871. It existed before the split between anarchists and Marxists had taken place, and it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class during the Industrial Revolution...

in April-May 1871. He was wounded a third time as he led troops to the siege of the Panthéon

Panthéon, Paris

The Panthéon is a building in the Latin Quarter in Paris. It was originally built as a church dedicated to St. Genevieve and to house the reliquary châsse containing her relics but, after many changes, now functions as a secular mausoleum containing the remains of distinguished French citizens...

, and was promoted commandeur of the Légion d'honneur by Patrice Mac-Mahon

Patrice MacMahon, duc de Magenta

Marie Edme Patrice Maurice de Mac-Mahon, 1st Duke of Magenta was a French general and politician with the distinction Marshal of France. He served as Chief of State of France from 1873 to 1875 and as the first president of the Third Republic, from 1875 to 1879.-Early life:Born in Sully , in the...

. However, he was soon demoted (as his position was considered provisional), and his resignation in protest was rejected.

With backing from his direct superior, Henri d'Orléans, duc d'Aumale

Henri d'Orléans, duc d'Aumale

-Bibliophile:He was a noted collector of old manuscripts and books. His library remains at Chantilly.-Death:By his will of the June 3, 1884, however, he had bequeathed to the Institute of France his Chantilly estate, including the Château de Chantilly, with all the art-collection he had collected...

(incidentally, one of the sons of former king Louis-Philippe

Louis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I was King of the French from 1830 to 1848 in what was known as the July Monarchy. His father was a duke who supported the French Revolution but was nevertheless guillotined. Louis Philippe fled France as a young man and spent 21 years in exile, including considerable time in the...

), Boulanger was made a brigadier-general in 1880, and in 1882 War Minister Jean-Baptiste Billot

Jean-Baptiste Billot

Jean-Baptiste Billot - 31 May 1907, Paris) was a French general and politician.-Life:Jean-Baptiste Billot entered the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr in 1847, and on leaving it in 1849 joined the staff with the rank of sous-lieutenant...

appointed him director of infantry at the war office, enabling him to make a name as a military reformer (he took measures to improve morale

Morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps when discussing the morale of a group, is an intangible term used to describe the capacity of people to maintain belief in an institution or a goal, or even in oneself and others...

and efficiency). In 1884 he was appointed to command the army occupying Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

, but was recalled owing to his differences of opinion with Pierre-Paul Cambon, the political resident. He returned to Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, and began to take part in politics under the aegis of Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

and the Radicals

Liberalism and radicalism in France

Liberalism and radicalism in France do not form the same type of ideology. In fact, the main line of conflict in France during the 19th century was between monarchist opponents of the Republic and supporters of the Republic...

. In January 1886, when Charles de Freycinet

Charles de Freycinet

Charles Louis de Saulces de Freycinet was a French statesman and Prime Minister during the Third Republic; he belonged to the Opportunist Republicans faction. He was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences, and in 1890, the fourteen member to occupy seat the Académie française.-Early years:He...

was brought into power, Clemenceau used his influence to secure Boulanger's appointment as War Minister (replacing Jean-Baptiste-Marie Campenon). Clemenceau assumed Boulanger was a republican, because he was known not to attend Mass. However Boulanger would soon prove himself a conservative and monarchist.

Minister

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

- in doing so, came to be regarded as the man destined to serve that revenge (nicknamed Général Revanche). He also managed to quell the major workers' strike

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

in Decazeville

Decazeville

Decazeville is a commune in the Aveyron department in the Midi-Pyrénées region in southern France.The commune was created in the 19th century because of the Industrial Revolution and was named after the Duke of Decazes , the founder of the factory that created the town.-History:The town is built...

. A minor scandal arose when Philippe, comte de Paris

Philippe, Comte de Paris

Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris was the grandson of Louis Philippe I, King of the French. He was a claimant to the French throne from 1848 until his death.-Early life:...

, the nominal inheritor of the French throne in the eyes of Orléanist

Orléanist

The Orléanists were a French right-wing/center-right party which arose out of the French Revolution. It governed France 1830-1848 in the "July Monarchy" of king Louis Philippe. It is generally seen as a transitional period dominated by the bourgeoisie and the conservative Orleanist doctrine in...

monarchists

Monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the establishment, preservation, or restoration of a monarchy as a form of government in a nation. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government out of principle, independent from the person, the Monarch.In this system, the Monarch may be the...

, married his daughter Amélie to Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

's Carlos I

Carlos I of Portugal

-Assassination:On 1 February 1908 the royal family returned from the palace of Vila Viçosa to Lisbon. They travelled by train to Barreiro and, from there, they took a steamer to cross the Tagus River and disembarked at Cais do Sodré in central Lisbon. On their way to the royal palace, the open...

, in a lavish wedding that provoked fears of anti-Republican ambitions. The French Parliament hastily passed a law expelling all possible claimants to the crown from French territories. Boulanger found himself in the unusual posture of a monarchist sympathiser forced to communicate to d'Aumale his expulsion from the armed forces. He received the adulation of the public and press after the Sino-French War

Sino-French War

The Sino–French War was a limited conflict fought between August 1884 and April 1885 to decide whether France should replace China in control of Tonkin . As the French achieved their war aims, they are usually considered to have won the war...

, when France's victory added Tonkin

Tonkin

Tonkin , also spelled Tongkin, Tonquin or Tongking, is the northernmost part of Vietnam, south of China's Yunnan and Guangxi Provinces, east of northern Laos, and west of the Gulf of Tonkin. Locally, it is known as Bắc Kỳ, meaning "Northern Region"...

to its colonial empire

French colonial empires

The French colonial empire was the set of territories outside Europe that were under French rule primarily from the 17th century to the late 1960s. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the colonial empire of France was the second-largest in the world behind the British Empire. The French colonial empire...

. He also vigorously pressed for the accelerated adoption, in 1886, of the new and technically revolutionary Lebel rifle which introduced for the first time smokeless powder

Smokeless powder

Smokeless powder is the name given to a number of propellants used in firearms and artillery which produce negligible smoke when fired, unlike the older gunpowder which they replaced...

high-velocity ammunition.

On Freycinet's defeat in December of the same year, Boulanger was retained by René Goblet

René Goblet

René Goblet was a French politician, Prime Minister of France for a period in 1886–1887.He was born at Aire-sur-la-Lys, Pas-de-Calais and was trained in law. Under the Second Empire, he helped found a Liberal journal, Le Progrès de la Somme, and in July 1871 he was sent by the département of the...

at the war office. Confident of political support, the general began provoking the Germans: he ordered military facilities to be built in the border region of Belfort

Belfort

Belfort is a commune in the Territoire de Belfort department in Franche-Comté in northeastern France and is the prefecture of the department. It is located on the Savoureuse, on the strategically important natural route between the Rhine and the Rhône – the Belfort Gap or Burgundian Gate .-...

, forbade the export of horses to German markets, and even instigated a ban on representations of Lohengrin

Lohengrin (opera)

Lohengrin is a romantic opera in three acts composed and written by Richard Wagner, first performed in 1850. The story of the eponymous character is taken from medieval German romance, notably the Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach and its sequel, Lohengrin, written by a different author, itself...

. Germany responded by calling to arms more than 70,000 reservist

Reservist

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person is usually a former active-duty member of the armed...

s in February 1887; after the Schnaebele incident (April 1887), war was averted, but Boulanger was perceived by his supporters as coming out on top against Bismarck. For the Goblet government, Boulanger was an embarrassment and risk, and became engaged in a dispute with Foreign Minister

Minister of Foreign Affairs (France)

Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs ), is France's foreign affairs ministry, with the headquarters located on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris close to the National Assembly of France. The Minister of Foreign and European Affairs in the government of France is the cabinet minister responsible for...

Émile Flourens

Émile Flourens

Émile Flourens was a French politician.He was the younger brother of Gustave Flourens....

. On May 17, Goblet was voted out of office and replaced by Maurice Rouvier

Maurice Rouvier

Maurice Rouvier was a French statesman.He was born in Aix-en-Provence, and spent his early career in business at Marseille. He supported Léon Gambetta's candidature there in 1867, and in 1870 he founded an anti-imperial journal, L'Egalité. Becoming secretary general of the prefecture of...

. The latter sacked Boulanger, and replaced him with Théophile Adrien Ferron on May 30.

The rise of Boulangisme

The government was astonished by the revelation that Boulanger had received around 100,000 votes for the partial election in SeineSeine (département)

Seine was a département of France encompassing Paris and its immediate suburbs. Its préfecture was Paris and its official number was 75. The Seine département was abolished in 1968 and its territory divided among four new départements....

, without him even being a candidate. He was removed from the Paris region and sent to the provinces, appointed commander of the troops stationed in Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand is a city and commune of France, in the Auvergne region, with a population of 140,700 . Its metropolitan area had 409,558 inhabitants at the 1999 census. It is the prefecture of the Puy-de-Dôme department...

. Upon his departure on July 8, a crowd of ten thousand took the Gare de Lyon

Gare de Lyon

Paris Lyon is one of the six large railway termini in Paris, France. It is the northern terminus of the Paris–Marseille railway. It is named after the city of Lyon, a stop for many long-distance trains departing here, most en route to the south of France. In general the station's SNCF services run...

by storm, covering his train with poster

Poster

A poster is any piece of printed paper designed to be attached to a wall or vertical surface. Typically posters include both textual and graphic elements, although a poster may be either wholly graphical or wholly text. Posters are designed to be both eye-catching and informative. Posters may be...

s titled Il reviendra ("He will come back"), and blocking the railway, but he was smuggled through on a switch engine.

The general decided to gather support for his own movement, an eclectic one that capitalized on the frustrations of French conservatism

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

, advocating the three principles of Revanche (Revenge on Germany), Révision (Revision of the Constitution), Restoration (the return to monarchy). The common reference to it has become Boulangisme, a term used by its partisans and adversaries alike. Immediately, the option was backed by notable conservative figures such as Henri Rochefort, Count

Count

A count or countess is an aristocratic nobleman in European countries. The word count came into English from the French comte, itself from Latin comes—in its accusative comitem—meaning "companion", and later "companion of the emperor, delegate of the emperor". The adjective form of the word is...

Arthur Dillon, Alfred Joseph Naquet

Alfred Joseph Naquet

Alfred Joseph Naquet , French chemist and politician, was born at Carpentras , on the 6th of October 1834. He became professor in the faculty of medicine in Paris in 1863, and in the same year professor of chemistry at Palermo, where he delivered his lectures in Italian.He lost his professorship in...

, Anne de Mortemart-Rochechouart (Duchess of Uzès, who financed him with immense sums), Arthur Meyer

Arthur Meyer (journalist)

Arthur Meyer was a French press baron. He was director of Le Gaulois, a notable conservative French daily newspaper that was eventually taken over by Le Figaro in 1929...

, Paul Déroulède

Paul Déroulède

- Early life :Déroulède was born in Paris. He was published first as a poet in the magazine Revue nationale, with the pseudonym "Jean Rebel". In 1869 he produced, at the Théâtre Français, a one-act drama in verse named Juan Strenner.- Military career :...

(and his Ligue des Patriotes

Ligue des Patriotes

The Ligue des Patriotes was a French far right league, founded in 1882 by the nationalist poet Paul Déroulède, historian Henri Martin, and Felix Faure. The Ligue began as a non-partisan nationalist league calling for 'revanche' against Germany, and literally means "League of Patriots"...

).

After the political corruption

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

scandal surrounding the President's son-in-law Daniel Wilson, who was secretly selling Legion of Honor medals to anyone who wanted one, the Republican government was brought into disrepute and Boulanger's popular appeal rose in contrast. His position became essential after President

President of the French Republic

The President of the French Republic colloquially referred to in English as the President of France, is France's elected Head of State....

Jules Grévy

Jules Grévy

François Paul Jules Grévy was a President of the French Third Republic and one of the leaders of the Opportunist Republicans faction. Given that his predecessors were monarchists who tried without success to restore the French monarchy, Grévy is seen as the first real republican President of...

was forced to resign due to the scandal: in January 1888, the boulangistes promised to back any candidate for the presidency that would in turn offer his support to Boulanger for the post of War Minister (France was a parliamentary republic

Parliamentary system

A parliamentary system is a system of government in which the ministers of the executive branch get their democratic legitimacy from the legislature and are accountable to that body, such that the executive and legislative branches are intertwined....

). The crisis was cut short by the election of Marie François Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot was a French statesman and the fourth president of the Third French Republic. He served as the President of France from 1887 until his assassination in 1894.-Early life:...

and the appointment of Pierre Tirard

Pierre Tirard

Pierre Emmanuel Tirard was a French politician.He was born to French parents in Geneva, Switzerland. After studying in his native town, Tirard became a civil engineer. After five years of government service he resigned to become a jewel merchant...

as Prime Minister - Tirard refused to include Boulanger in his cabinet. During the period, Boulanger was in Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

, where he met with Jérôme Napoleon Bonaparte II

Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte II

Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte II was a son of Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte and Susan May Williams.-Biography:...

, technically a Bonapartist

Bonapartist

In French political history, Bonapartism has two meanings. In a strict sense, this term refers to people who aimed to restore the French Empire under the House of Bonaparte, the Corsican family of Napoleon Bonaparte and his nephew Louis...

, who offered his full support to the cause. The Bonapartists had attached themselves to the general, and even the Comte de Paris encouraged his followers to support him. Once seen as a republican, Boulanger showed his true colors in the camp of the conservative monarchists. On March 26, 1888 he was expelled from the army. The day after, Daniel Wilson had his imprisonment repealed. It seemed to the French people that honorable generals were punished while corrupt politicians were spared, further increasing Boulanger's popularity.

Although he was not in fact a legal candidate for the French Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of deputies is the name given to a legislative body such as the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or can refer to a unicameral legislature.-Description:...

(since he was a military man), Boulanger ran with Bonapartist backing in seven separate départements during the remainder of 1888. Boulangiste candidates were present in every département. Consequently, he and many of his supporters were voted to the Chamber, and accompanied by a large crowd on July 12, the day of their swearing in - the general himself was elected in the constituency of Nord. The boulangistes were, nonetheless, a minority in the Chamber. Since Boulanger could not pass legislation, his actions were directed to maintaining his public image. Neither his failure as an orator nor his defeat in a duel with Charles Thomas Floquet, then an elderly civilian and the minister of the interior, reduced the enthusiasm of his popular following.

During 1888 his personality was the dominating feature of French politics, and, when he resigned his seat as a protest against the reception given by the Chamber to his proposals, constituencies vied with one another in selecting him as their representative. His name was the theme of the popular song C'est Boulanger qu'il nous faut ("Boulanger is the One We Need"), he and his black horse became the idol of the Parisian population, and he was urged to run for the presidency. The general agreed, but his personal ambitions soon alienated his republican supporters, who recognised in him a potential military dictator

Military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a form of government where in the political power resides with the military. It is similar but not identical to a stratocracy, a state ruled directly by the military....

. Numerous monarchists continued to give him financial aid, even though Boulanger saw himself as a leader rather than a restorer of kings.

Decline

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

seemed probable and desirable among his supporters. Boulanger had now become a threat to the parliamentary Republic. Had he immediately placed himself at the head of a revolt he might have effected the coup which many of his partisans had worked for, and might even have governed France; but the opportunity passed with his procrastination on January 27. According to Lady Randolph Churchill "[a]ll his thoughts were centred in and controlled by her who was the mainspring of his life. After the plebiscite...he rushed off to Madame Bonnemain's house and could not be found."

Boulanger decided that it would be better to contest the general election and take power legally. This, however, gave his enemies the time they needed to strike back. Ernest Constans, the Minister of the Interior

Minister of the Interior (France)

The Minister of the Interior in France is one of the most important governmental cabinet positions, responsible for the following:* The general interior security of the country, with respect to criminal acts or natural catastrophes...

, decided to investigate the matter, and attacked the Ligue des Patriotes using the law banning the activities of secret societies

Secret society

A secret society is a club or organization whose activities and inner functioning are concealed from non-members. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence agencies or guerrilla insurgencies, which hide their...

.

Shortly afterward the French government issued a warrant for Boulanger's arrest for conspiracy

Conspiracy (political)

In a political sense, conspiracy refers to a group of persons united in the goal of usurping or overthrowing an established political power. Typically, the final goal is to gain power through a revolutionary coup d'état or through assassination....

and treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

able activity. To the astonishment of his supporters, on April 1 he fled from Paris before it could be executed, going first to Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

and then to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. On April 4, the Parliament stripped him of his immunity from prosecution

Parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity, also known as legislative immunity, is a system in which members of the parliament or legislature are granted partial immunity from prosecution. Before prosecuting, it is necessary that the immunity be removed, usually by a superior court of justice or by the parliament itself...

; the French Senate

French Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Parliament of France, presided over by a president.The Senate enjoys less prominence than the lower house, the directly elected National Assembly; debates in the Senate tend to be less tense and generally enjoy less media coverage.-History:France's first...

condemned him, Rochefort, and Count Dillon for treason, sentencing all three to deportation

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

and confinement.

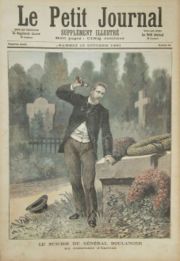

Death

After his flight, support for him dwindled, and the Boulangists were defeated in the general elections of July 1889 (after the government forbade Boulanger from running). Boulanger himself went to live in JerseyJersey

Jersey, officially the Bailiwick of Jersey is a British Crown Dependency off the coast of Normandy, France. As well as the island of Jersey itself, the bailiwick includes two groups of small islands that are no longer permanently inhabited, the Minquiers and Écréhous, and the Pierres de Lecq and...

before returning to the Ixelles Cemetery

Ixelles Cemetery

The Ixelles Cemetery , located in Ixelles in the southern part of Brussels, is one of the major cemeteries in Belgium....

in Brussels in September 1891 to commit suicide by a bullet to the head on the grave of his mistress, Madame de Bonnemains (née Marguerite Crouzet

Marguerite Crouzet

Marguerite Crouzet was the mistress of Georges Boulanger. She died in July 1891. A few months later Georges Boulanger was to commit suicide on her grave....

) who had died the preceding July. He was interred in the same grave.

Several incidents followed Boulanger's death, including an armed attack carried out by a boulangiste against the Republican politician Jules Ferry

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry was a French statesman and republican. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion.- Early life :Born in Saint-Dié, in the Vosges département, France, he studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to...

, in December of the same year. Although largely discredited, the trend started by Boulanger was still visible inside the far right

Far right

Far-right, extreme right, hard right, radical right, and ultra-right are terms used to discuss the qualitative or quantitative position a group or person occupies within right-wing politics. Far-right politics may involve anti-immigration and anti-integration stances towards groups that are...

(the anti-Dreyfusards) during France's next major scandal, the Dreyfus Affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

. Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

i historian Zeev Sternhell

Zeev Sternhell

Zeev Sternhell is an Israeli historian and one of the world's leading experts on Fascism. Sternhell headed the Department of Political Science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and writes for Haaretz newspaper.-Biography:...

cites boulangisme as a major influence on Fascism

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

, alongside Anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a branch of anarchism which focuses on the labour movement. The word syndicalism comes from the French word syndicat which means trade union , from the Latin word syndicus which in turn comes from the Greek word σύνδικος which means caretaker of an issue...

and the Cercle Proudhon

Cercle Proudhon

The Cercle Proudhon was a political group founded in France on December 16, 1911 by George Valois and Édouard Berth. It was to include such people as French writer Pierre Drieu La Rochelle.-History:...

.

Quotes

- "We can finally renounce our unfortunate defensive policy [towards Germany]; France ought to increasingly follow the offensive policy." (1886, during a speech in LibourneLibourneLibourne is a commune in the Gironde department in Aquitaine in southwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.It is the wine-making capital of northern Gironde and lies near Saint-Émilion and Pomerol.-Geography:...

) - "Boulangisme: (...) 'a vague and mysticalMysticismMysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

aspiration of a nation towards a democraticDemocracyDemocracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

, authoritarianAuthoritarianismAuthoritarianism is a form of social organization characterized by submission to authority. It is usually opposed to individualism and democracy...

, liberating ideal; the state of mind of a country that is searching, after the various deceptions to which she was exposed by the established parties which she had trusted up to then, and outside the usual ways, something else altogether, without knowing either what or how, and summoning all those who are dissatisfied and vanquished in its search for the unknown.' (...) 'General Boulanger was born out of this state of mind. He did not create the boulangisme, it is boulangisme that created him. He had the chance to arrive at the psychological and spiritual moment from which he profits." (Arthur MeyerArthur Meyer (journalist)Arthur Meyer was a French press baron. He was director of Le Gaulois, a notable conservative French daily newspaper that was eventually taken over by Le Figaro in 1929...

in Le GauloisLe GauloisLe Gaulois was a French daily newspaper, founded in 1868 by Edmond Tarbe and Henri de Pene. After a printing stoppage, it was revived by Arthur Meyer in 1882 with notable collaborators Paul Bourget, Alfred Grévin, Abel Hermant, and Ernest Daudet...

, October 11, 1889) - "A Saint ArnaudJacques Leroy de Saint ArnaudArmand-Jacques Leroy de Saint-Arnaud was a French soldier and Marshal of France during the 19th century...

of the café-concertCabaretCabaret is a form, or place, of entertainment featuring comedy, song, dance, and theatre, distinguished mainly by the performance venue: a restaurant or nightclub with a stage for performances and the audience sitting at tables watching the performance, as introduced by a master of ceremonies or...

." (Jules FerryJules FerryJules François Camille Ferry was a French statesman and republican. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion.- Early life :Born in Saint-Dié, in the Vosges département, France, he studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to...

on Boulanger) - "Five minutes past midnight, gentlemen. It's been five minutes since boulangisme has started to decrease." (a boulangiste on January 27, immediately after Boulanger's refusal to lead a coup)

- "He died as he has lived: a second lieutenantSecond LieutenantSecond lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

." (Georges ClemenceauGeorges ClemenceauGeorges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

upon hearing news of Boulanger's suicide)

In popular culture

Général Boulanger inspired the Jean RenoirJean Renoir

Jean Renoir was a French film director, screenwriter, actor, producer and author. As a film director and actor, he made more than forty films from the silent era to the end of the 1960s...

movie Elena and Her Men

Elena and Her Men

Elena and Her Men is a 1956 film directed by Jean Renoir and starring Ingrid Bergman, and was her first film after leaving husband Roberto Rossellini. The film's original French title was Elena et les Hommes and in English-speaking countries, the title was Paris Does Strange Things.-External links:*...

, a musical fantasy loosely based on the end of his political career. The role of Général François Rollan, a Boulanger-like character, was played by Jean Marais

Jean Marais

-Biography:A native of Cherbourg, France, Marais starred in several movies directed by Jean Cocteau, for a time his lover, most famously Beauty and the Beast and Orphée ....

.

IMDB notes that there was also a French television programme about Boulanger in the early 1980s, La Nuit du général Boulanger, where Boulanger is played by Maurice Ronet

Maurice Ronet

Maurice Ronet was a French film actor, director and writer.-Biography:Maurice Ronet was born Maurice Julien Marie Robinet in Nice, Alpes Maritimes, the only child of professional stage actors Émile Robinet and Gilberte Dubreuil. He made his stage debut in 1941, along side his parents, in Sacha...

.

He is quoted as the one who authorised the institution of the "Suicide Bureau" in Guy de Maupassant

Guy de Maupassant

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant was a popular 19th-century French writer, considered one of the fathers of the modern short story and one of the form's finest exponents....

's short story "The Magic Couch", reportedly "the only good thing he did".

Sources

- Michael Burns, Rural Society and French Politics, Boulangism and the Dreyfus Affair, 1886-1900, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Adrien Dansette, Le Boulangisme, De Boulanger à la Révolution Dreyfusienne, 1886-1890, Paris: Libraire Academique Perrin, 1938.

- Raoul Girardet, Le Nationalisme français, 1871-1914, Paris: A. Colin, 1966.

- Patrick Hutton, "The Impact of the Boulangist Crisis on the Guesdist Party at Bordeaux," French Historical Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 1973, pp. 226–44.

- Patrick Hutton, "Popular Boulangism and the Advent of Mass Politics in France, 1886-90," Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 11, no. 1, 1976, pp. 85–106.

- William D. Irvine, The Boulanger Affair Reconsidered, Royalism, Boulangism, and the Origins of the Radical Right in France, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Jacques Néré, Le Boulangisme et la Presse, Paris: A. Colin, 1964.

- René Rémond, The Right Wing in France from 1815 to de Gaulle, translated by James M. Laux, 2nd American ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969.

- Odile Rudelle, La République Absolue, Aux origines de l'instabilité constitutionelle de la France républicaine, 1870-1889, Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1982.

- Peter M. Rutkoff, Revanche and Revision, The Ligue des Patriotes and the Origins of the Radical Right in France, 1882-1900, Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981.

- Frederic Seager, The Boulanger Affair, Political Crossroads of France, 1886-1889, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1969.

- Zeev Sternhell, La Droite Révolutionnaire, 1885–1914; Les Origines Françaises du Fascisme, Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

- Zeev Sternhell, Maurice Barrès et le Nationalisme Français, Paris: A. Colin, 1972.