.gif)

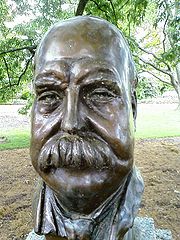

George Reid (Australian politician)

Encyclopedia

Sir George Houstoun Reid, GCB

, GCMG

, KC (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australia

n politician, Premier of New South Wales and the fourth Prime Minister of Australia

.

Reid was the last leader of the Liberal tendency in New South Wales

, led by Charles Cowper

and Henry Parkes

and which Reid organised as the Free Trade and Liberal Association

in 1889. He was more effective as Premier of New South Wales from 1894 to 1899 than he was as Prime Minister in 1904 and 1905. This partly reflected the disappearance of the rationale of the Free Trade Party with the imposition of tariffs by the federal government and the disappearance of the political centre ground with the rise of the Australian Labor Party

. Although a supporter of Federation, he took an equivocal position on it during the campaign for the first referendum in June 1898, earning himself the nickname of "Yes-No Reid."

, Renfrewshire

, Scotland

, son of a Church of Scotland

minister, migrated to Victoria

with his family in 1852. His family was one of many Presbyterian families brought out from Scotland by Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang

, with whom his father worked at Scots' Church, Sydney. He was educated at Scotch College

, where he said he could "read, write and count fairly well", but had "a lazy horror of Greek" and no appetite for the "wide range of metaphysical propositions" which formed part of the curriculum.

At the age of 13, Reid and his family moved to Sydney

, and obtained a job as a clerk. At the age of 15 he joined the School of Arts Debating Society, and according to his autobiography, a more crude novice than he was never began the practise of public speaking. He became an assistant accountant in the Colonial Treasury in 1864 and rose rapidly and became head of the Attorney-General's department in 1878. In 1875 he had published his Five Essays on Free Trade, which brought him an honorary membership of the Cobden Club

, and in 1878 the government published his New South Wales, the Mother Colony of the Australians, for distribution in Europe. In 1876 he began to study law seriously, which would the independent income necessary to pursue a parliamentary career (given that parliamentary service was unpaid at the time). In 1879, Reid qualified as a barrister

.

detested Reid, describing him as "inordinately vain and resolutely selfish" and their cold relationship would affect both their later careers.

Reid was elected top of the poll to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

as a member for the four-member electoral district of East Sydney

in 1880. He was not active at first, as he was building up his legal practice, although he was concerned to reform the Robertson Land Acts

, which had not prevented 96 land holders from controlling eight million acres (32,000 km²) between them. Henry Parkes

and John Robertson attempted to make minor amendments to the land acts but were defeated and at the subsequent election Parkes' party lost many seats.

The new premier, Alexander Stuart

, offered Reid the position of Colonial Treasurer in January 1883, but he thought it wiser to accept the junior office of Minister for Public Instruction. He was 14 months in office and succeeded in passing a much improved Education Act, which included the establishment of the first government high schools in the leading towns, technical schools (which became a model for the other colonies) and the provision of evening lectures at the university.

In February 1884, Reid lost his seat in parliament owing to a technicality; the necessary notice had not appeared in the Government Gazette declaring that the Minister for Public Instruction was a position that a parliamentarian could hold instead of being excluded from parliament for holding an "office of profit" . At the by-election Reid was defeated by a small majority as a result of the government's financial harships due to the loss of revenue as a result of the suspension of land sales. In 1885 he was re-elected in East Sydney and took a great part in the free trade or protection issue. He supported Sir Henry Parkes on the free trade side but, when Parkes came into power in 1887, declined a seat in his ministry. Parkes offered him a portfolio two years later and Reid again refused. He did not like Parkes personally and felt he would be unable to work with him. When payment of members of parliament was passed Reid, who had always opposed it, paid the amount of his salary into the treasury. Reid had become Sydney's leading barrister by impressing juries by his cross-examinations and was made a Queen's Counsel

in 1898.

In September 1891, the Parkes ministry was defeated, the Dibbs

In September 1891, the Parkes ministry was defeated, the Dibbs

government succeeded it, and Parkes retired from the leadership of the Free Trade Party

. Reid was elected leader of the opposition in his place. In 1891, he married Florence (Flora) Ann Brumby

, who was 23 years old to his 46. He managed to form his party into a coherent group although it "ran the whole gamut from conservative Sydney merchants through middle-class intellectuals to reformers who wished to replace indirect by direct taxation for social reasons."

At the 1894 election he made the establishment of a real free trade tariff with a system of direct taxation the main item of his policy, and had a great victory. Edmund Barton

and other well-known protectionists lost their seats, the Labor

following was reduced from 30 to 18, and Reid formed his first cabinet. One of his earliest measures was a new lands bill which provided for the division of pastoral leases into two halves, one of which was to be open to the free selector, while the pastoral lessee got some security of tenure for the other half. Classification of crown lands according to their value was provided for, and the free selector, or his transferee, had to reside on the property.

Parkes at an early stage of the session raised the question of federation again, and Reid invited the premiers of the other colonies to meet in conference on 29 January 1895. As a consequence of this conference an improved bill was drafted which ensured that both the people and the parliaments of the various colonies should be consulted. Meanwhile Reid had great trouble in passing his land and income tax bills. When he did get them through the Assembly the Council

threw them out. Reid obtained a dissolution, was victorious at the polls, and heavily defeated Parkes for the new single-member electoral district of Sydney-King

. He eventually succeeded in passing his acts, which were moderate, but strenuously opposed by the Council, and it was only the fear that the chamber might be swamped with new appointments that eventually wore down the opposition. Reid was also successful in bringing in reforms in the keeping of public accounts and in the civil service generally. Other acts dealt with the control of inland waters, and much needed legislation relating to public health, factories, and mining, was also passed. In five years he had achieved more than any of his predecessors.

Reid supported the federation of the Australian colonies, but since the campaign was led by his Protectionist

Reid supported the federation of the Australian colonies, but since the campaign was led by his Protectionist

opponent Edmund Barton

he did not take a leading role. He was dissatisfied by the draft constitution, especially the power of a Senate, elected on the basis of States rather than population, to reject money bills. In the referendum campaign after the close of the Australasian Federal Convention, Reid, on 28 March 1898, made his famous "Yes-No" speech at the Sydney town hall. He told his audience that he intended to deal with the bill "with the deliberate impartiality of a judge addressing a jury". After speaking for an hour and three-quarters the audience was still uncertain about his verdict. He ended up by saying that while he felt he could not become a deserter to the cause he would not recommend any course to the electors. He consistently kept this attitude until the poll was taken on 3 June 1898. This earned him the nickname "Yes-No Reid." The referendum in New South Wales resulted in a small majority in favour, but the yes votes fell about 8000 below the required number of 80,000. Subsequently Reid was able to secure greater concessions for New South Wales.

At the general election held soon after, Barton accepted Reid's challenge to contest the East Sydney seat and Reid defeated him, but his party came back with a reduced majority. Reid fought for federation at the second referendum and it was carried in New South Wales by a majority of nearly 25,000, 107,420 Votes being cast in favour of it. "A bizarre combination of the Labor Party, protectionists, Federation enthusiasts and die-hard anti-Federation free traders" censured Reid for paying the expenses of J. C. Neild

who had been commissioned to report on old-age pensions, prior to parliamentary approval. Governor Beauchamp

refused Reid a dissolution and he resigned. By this time Reid had grown extremely overweight and sported a walrus moustache and a monocle, but his buffoonish image concealed a shrewd political brain.

at the 1901 election. The Free Trade Party won 28 out of 75 seats in the House of Representatives

, and 17 out of 36 seats in the Senate

. Labor no longer trusted Reid and gave their support to the Edmund Barton

Protectionist Party

government, so Reid became the first Leader of the Opposition

, a position well-suited to his robust debating style and rollicking sense of humour. In the long tariff debate Reid was at a disadvantage as parliament was sitting in Melbourne

and he could not entirely neglect his practice as a barrister in Sydney, as his parliamentary income was less than a tenth of his income from his legal practice. With the rise of the Labor Party, the Free Trade Party had lost much of the middle ground to Barton and his followers, and it was increasingly dependent on conservatives, including militant Protestants.

On 18 August 1903, Reid resigned (the first member of the House of Representatives to do so) and challenged the government to oppose his re-election on the issue of its refusal to accept a system of equal electoral districts. He contested the by-election for East Sydney

on 4 September, and won it back. He is the only person in Australian federal parliamentary history to win back his seat at a by-election triggered by his own resignation.

Alfred Deakin

took over from Barton as Prime Minister and leader of the Protectionists. At the 1903 election, the Free Trade Party won 24 seats, with the Labor vote increasing mainly at the expense of the Protectionists. In August 1904, when the Watson

government resigned, he became Prime Minister. He was the first former state premier to become Prime Minister (the only other to date being Joseph Lyons

). Reid did not have a majority in either House, and he knew it would be only a matter of time before the Protectionists patched up their differences with Labor, so he enjoyed himself in office while he could. In July 1905 the other two parties duly voted him out, and he left office with a good grace. The Protectionist vote dropped again with more seats lost at the 1906 election. By this time, Reid had renamed the Free Trade Party the Anti-Socialist Party, and at the election won 26 seats (up two), to Labor on 26 seats (up three). The Deakin government continued with Labor support for the time being, despite only holding 16 seats after losing 10, although with another 5 independent Protectionists.

In 1907-08, Reid strenuously resisted Deakin's commitment to increase tariff rates. In 1908, when Deakin proposed the Commonwealth Liberal Party

, a "Fusion" of the two non-Labor parties, Reid stood aside from the leadership. Joseph Cook

was made leader until the parties merged.

On 24 December 1909 he resigned from Parliament (he was the first Member to have resigned twice), however his seat was left vacant until the 1910 election

. His seat of East Sydney

was won by Labor's John West

, in an election which saw Labor win 42 of 75 seats, against the CLP on 31 seats. Labor also won a majority in the Senate.

In 1910, Reid was appointed as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

Reid was extremely popular in Britain, and in 1916, when his term as High Commissioner ended, he was returned unopposed to the House of Commons for the seat of St George, Hanover Square

Reid was extremely popular in Britain, and in 1916, when his term as High Commissioner ended, he was returned unopposed to the House of Commons for the seat of St George, Hanover Square

as a Unionist

candidate, where he acted as a spokesman for the self-governing Dominion

s in supporting the war effort. He died suddenly in London in September 1918, aged 73 of cerebral thrombosis, survived by his wife and their two sons and daughter. She had become Dame Flora Reid

GBE in 1917. He is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery

.

Reid's posthumous reputation suffered from the general acceptance of protectionist policies by other parties, as well as from his buffoonish public image. In 1989 W. G. McMinn published George Reid (Melbourne University Press), a serious biography designed to rescue Reid from his reputation as a clownish reactionary and attempt to show his Free Trade policies as having been vindicated by history.

In 1897 Reid was made an Honorary Doctor of Civil Law (DCL) by Oxford University

In 1897 Reid was made an Honorary Doctor of Civil Law (DCL) by Oxford University

. Reid was also appointed a member of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (1904), a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

(1911) and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

(1916).

In 1969 he was honoured on a postage stamp

bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

.

|-

|-

|-

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, GCMG

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

, KC (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n politician, Premier of New South Wales and the fourth Prime Minister of Australia

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

.

Reid was the last leader of the Liberal tendency in New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

, led by Charles Cowper

Charles Cowper

Sir Charles Cowper, KCMG was an Australian politician and the Premier of New South Wales on five different occasions from 1856 to 1870....

and Henry Parkes

Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, GCMG was an Australian statesman, the "Father of Federation." As the earliest advocate of a Federal Council of the colonies of Australia, a precursor to the Federation of Australia, he was the most prominent of the Australian Founding Fathers.Parkes was described during his...

and which Reid organised as the Free Trade and Liberal Association

Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states and renamed the Anti-Socialist Party in 1906, was an Australian political party, formally organised between 1889 and 1909...

in 1889. He was more effective as Premier of New South Wales from 1894 to 1899 than he was as Prime Minister in 1904 and 1905. This partly reflected the disappearance of the rationale of the Free Trade Party with the imposition of tariffs by the federal government and the disappearance of the political centre ground with the rise of the Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

. Although a supporter of Federation, he took an equivocal position on it during the campaign for the first referendum in June 1898, earning himself the nickname of "Yes-No Reid."

Early life

Reid was born in JohnstoneJohnstone

Johnstone is a town in the council area of Renfrewshire and larger historic county of the same name in the west central Lowlands of Scotland.The town lies three miles west of neighbouring Paisley and twelve miles west of the centre of the city of Glasgow...

, Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire is one of 32 council areas used for local government in Scotland. Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Renfrewshire, the others being Inverclyde to the west and East Renfrewshire to the east...

, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, son of a Church of Scotland

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland, known informally by its Scots language name, the Kirk, is a Presbyterian church, decisively shaped by the Scottish Reformation....

minister, migrated to Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

with his family in 1852. His family was one of many Presbyterian families brought out from Scotland by Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang

John Dunmore Lang

John Dunmore Lang , Australian Presbyterian clergyman, writer, politician and activist, was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian republicanism.-Background and Family:...

, with whom his father worked at Scots' Church, Sydney. He was educated at Scotch College

Scotch College, Melbourne

Scotch College, Melbourne is an independent, Presbyterian, day and boarding school for boys, located in Hawthorn, an inner-eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia....

, where he said he could "read, write and count fairly well", but had "a lazy horror of Greek" and no appetite for the "wide range of metaphysical propositions" which formed part of the curriculum.

At the age of 13, Reid and his family moved to Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

, and obtained a job as a clerk. At the age of 15 he joined the School of Arts Debating Society, and according to his autobiography, a more crude novice than he was never began the practise of public speaking. He became an assistant accountant in the Colonial Treasury in 1864 and rose rapidly and became head of the Attorney-General's department in 1878. In 1875 he had published his Five Essays on Free Trade, which brought him an honorary membership of the Cobden Club

Cobden Club

The Cobden Club was a political gentlemen's club in London founded in 1866 for believers in Free Trade doctrine, and named in honour of Richard Cobden, who had died the year before....

, and in 1878 the government published his New South Wales, the Mother Colony of the Australians, for distribution in Europe. In 1876 he began to study law seriously, which would the independent income necessary to pursue a parliamentary career (given that parliamentary service was unpaid at the time). In 1879, Reid qualified as a barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

.

Political career

Reid's career was aided by his quick wit and entertaining oratory; he was described as being "perhaps the best platform speaker in the Empire", both amusing and informing to his audiences "who flocked to his election meetings as to popular entertainment". In one particular incident his sense quick wit and affinity for humour were demonstrated when a heckler pointed to his ample paunch and exclaimed "What are you going to call it, George?" to which Reid replied: "If it's a boy, I'll call it after myself. If it's a girl I'll call it Victoria. But if, as I strongly suspect, it's nothing but piss and wind, I'll name it after you." His humour however was not universally appreciated. Alfred DeakinAlfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin , Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including the...

detested Reid, describing him as "inordinately vain and resolutely selfish" and their cold relationship would affect both their later careers.

Reid was elected top of the poll to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The other chamber is the Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament House in the state capital, Sydney...

as a member for the four-member electoral district of East Sydney

Electoral district of East Sydney

East Sydney was an electoral district for the Legislative Assembly in the Australian State of New South Wales created in 1859 from part of the electoral district of Sydney, covering the eastern part of the current Sydney central business district, Woolloomooloo, Potts Point, Elizabeth Bay and...

in 1880. He was not active at first, as he was building up his legal practice, although he was concerned to reform the Robertson Land Acts

Robertson Land Acts

The Crown Lands Acts 1861 were introduced by the New South Wales Premier, John Robertson, in 1861 to reform land holdings and in particular to break the squatters' domination of land tenure...

, which had not prevented 96 land holders from controlling eight million acres (32,000 km²) between them. Henry Parkes

Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, GCMG was an Australian statesman, the "Father of Federation." As the earliest advocate of a Federal Council of the colonies of Australia, a precursor to the Federation of Australia, he was the most prominent of the Australian Founding Fathers.Parkes was described during his...

and John Robertson attempted to make minor amendments to the land acts but were defeated and at the subsequent election Parkes' party lost many seats.

The new premier, Alexander Stuart

Alexander Stuart

Alexander Stuart may refer to:*Alexander Stuart , scientist, winner of the Copley Medal*Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart , United States Secretary of the Interior between 1850 and 1853...

, offered Reid the position of Colonial Treasurer in January 1883, but he thought it wiser to accept the junior office of Minister for Public Instruction. He was 14 months in office and succeeded in passing a much improved Education Act, which included the establishment of the first government high schools in the leading towns, technical schools (which became a model for the other colonies) and the provision of evening lectures at the university.

In February 1884, Reid lost his seat in parliament owing to a technicality; the necessary notice had not appeared in the Government Gazette declaring that the Minister for Public Instruction was a position that a parliamentarian could hold instead of being excluded from parliament for holding an "office of profit" . At the by-election Reid was defeated by a small majority as a result of the government's financial harships due to the loss of revenue as a result of the suspension of land sales. In 1885 he was re-elected in East Sydney and took a great part in the free trade or protection issue. He supported Sir Henry Parkes on the free trade side but, when Parkes came into power in 1887, declined a seat in his ministry. Parkes offered him a portfolio two years later and Reid again refused. He did not like Parkes personally and felt he would be unable to work with him. When payment of members of parliament was passed Reid, who had always opposed it, paid the amount of his salary into the treasury. Reid had become Sydney's leading barrister by impressing juries by his cross-examinations and was made a Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel , known as King's Counsel during the reign of a male sovereign, are lawyers appointed by letters patent to be one of Her [or His] Majesty's Counsel learned in the law...

in 1898.

Premier

George Dibbs

Sir George Richard Dibbs KCMG was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales on three occasions.-Early years:Dibbs was born in Sydney, son of Captain John Dibbs, who disappeared in the same year...

government succeeded it, and Parkes retired from the leadership of the Free Trade Party

Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states and renamed the Anti-Socialist Party in 1906, was an Australian political party, formally organised between 1889 and 1909...

. Reid was elected leader of the opposition in his place. In 1891, he married Florence (Flora) Ann Brumby

Flora Reid

Dame Florence "Flora" Reid GBE was the wife of the Prime Minister of Australia Sir George Reid.-Biodata:...

, who was 23 years old to his 46. He managed to form his party into a coherent group although it "ran the whole gamut from conservative Sydney merchants through middle-class intellectuals to reformers who wished to replace indirect by direct taxation for social reasons."

At the 1894 election he made the establishment of a real free trade tariff with a system of direct taxation the main item of his policy, and had a great victory. Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

and other well-known protectionists lost their seats, the Labor

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

following was reduced from 30 to 18, and Reid formed his first cabinet. One of his earliest measures was a new lands bill which provided for the division of pastoral leases into two halves, one of which was to be open to the free selector, while the pastoral lessee got some security of tenure for the other half. Classification of crown lands according to their value was provided for, and the free selector, or his transferee, had to reside on the property.

Parkes at an early stage of the session raised the question of federation again, and Reid invited the premiers of the other colonies to meet in conference on 29 January 1895. As a consequence of this conference an improved bill was drafted which ensured that both the people and the parliaments of the various colonies should be consulted. Meanwhile Reid had great trouble in passing his land and income tax bills. When he did get them through the Assembly the Council

New South Wales Legislative Council

The New South Wales Legislative Council, or upper house, is one of the two chambers of the parliament of New South Wales in Australia. The other is the Legislative Assembly. Both sit at Parliament House in the state capital, Sydney. The Assembly is referred to as the lower house and the Council as...

threw them out. Reid obtained a dissolution, was victorious at the polls, and heavily defeated Parkes for the new single-member electoral district of Sydney-King

Electoral district of Sydney-King

Sydney-King was an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales, created in 1894 in central Sydney from part of the electoral district of East Sydney and named after Governor King. It was initially east of George Street, north of Liverpool Street and...

. He eventually succeeded in passing his acts, which were moderate, but strenuously opposed by the Council, and it was only the fear that the chamber might be swamped with new appointments that eventually wore down the opposition. Reid was also successful in bringing in reforms in the keeping of public accounts and in the civil service generally. Other acts dealt with the control of inland waters, and much needed legislation relating to public health, factories, and mining, was also passed. In five years he had achieved more than any of his predecessors.

Federation

Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

opponent Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

he did not take a leading role. He was dissatisfied by the draft constitution, especially the power of a Senate, elected on the basis of States rather than population, to reject money bills. In the referendum campaign after the close of the Australasian Federal Convention, Reid, on 28 March 1898, made his famous "Yes-No" speech at the Sydney town hall. He told his audience that he intended to deal with the bill "with the deliberate impartiality of a judge addressing a jury". After speaking for an hour and three-quarters the audience was still uncertain about his verdict. He ended up by saying that while he felt he could not become a deserter to the cause he would not recommend any course to the electors. He consistently kept this attitude until the poll was taken on 3 June 1898. This earned him the nickname "Yes-No Reid." The referendum in New South Wales resulted in a small majority in favour, but the yes votes fell about 8000 below the required number of 80,000. Subsequently Reid was able to secure greater concessions for New South Wales.

At the general election held soon after, Barton accepted Reid's challenge to contest the East Sydney seat and Reid defeated him, but his party came back with a reduced majority. Reid fought for federation at the second referendum and it was carried in New South Wales by a majority of nearly 25,000, 107,420 Votes being cast in favour of it. "A bizarre combination of the Labor Party, protectionists, Federation enthusiasts and die-hard anti-Federation free traders" censured Reid for paying the expenses of J. C. Neild

John Neild

John Cash Neild was an English-born Australian politician who served as a Senator from New South Wales from 1901 to 1910....

who had been commissioned to report on old-age pensions, prior to parliamentary approval. Governor Beauchamp

William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp

William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp KG, KCMG, PC , styled Viscount Elmley until 1891, was a British Liberal politician. He was Governor of New South Wales between 1899 and 1901, a member of the Liberal administrations of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H. H...

refused Reid a dissolution and he resigned. By this time Reid had grown extremely overweight and sported a walrus moustache and a monocle, but his buffoonish image concealed a shrewd political brain.

Federal politics

Reid was elected to the first federal Parliament as the Member for East SydneyDivision of East Sydney

The Division of East Sydney was anAustralian Electoral Division in New South Wales. The division was created in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It was abolished in 1969. It was named for the suburb of East Sydney. It was located in the inner...

at the 1901 election. The Free Trade Party won 28 out of 75 seats in the House of Representatives

Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

, and 17 out of 36 seats in the Senate

Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives. Senators are popularly elected under a system of proportional representation. Senators are elected for a term that is usually six years; after a double dissolution, however,...

. Labor no longer trusted Reid and gave their support to the Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

Protectionist Party

Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

government, so Reid became the first Leader of the Opposition

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest party not in government in a Westminster System of parliamentary government...

, a position well-suited to his robust debating style and rollicking sense of humour. In the long tariff debate Reid was at a disadvantage as parliament was sitting in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

and he could not entirely neglect his practice as a barrister in Sydney, as his parliamentary income was less than a tenth of his income from his legal practice. With the rise of the Labor Party, the Free Trade Party had lost much of the middle ground to Barton and his followers, and it was increasingly dependent on conservatives, including militant Protestants.

On 18 August 1903, Reid resigned (the first member of the House of Representatives to do so) and challenged the government to oppose his re-election on the issue of its refusal to accept a system of equal electoral districts. He contested the by-election for East Sydney

East Sydney by-election, 1903

A by-election was held for the Australian House of Representatives electorate of East Sydney in New South Wales on 4 September 1903, a Friday. It was triggered by the resignation of George Reid on 18 August 1903...

on 4 September, and won it back. He is the only person in Australian federal parliamentary history to win back his seat at a by-election triggered by his own resignation.

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin , Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including the...

took over from Barton as Prime Minister and leader of the Protectionists. At the 1903 election, the Free Trade Party won 24 seats, with the Labor vote increasing mainly at the expense of the Protectionists. In August 1904, when the Watson

Chris Watson

John Christian Watson , commonly known as Chris Watson, Australian politician, was the third Prime Minister of Australia...

government resigned, he became Prime Minister. He was the first former state premier to become Prime Minister (the only other to date being Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

). Reid did not have a majority in either House, and he knew it would be only a matter of time before the Protectionists patched up their differences with Labor, so he enjoyed himself in office while he could. In July 1905 the other two parties duly voted him out, and he left office with a good grace. The Protectionist vote dropped again with more seats lost at the 1906 election. By this time, Reid had renamed the Free Trade Party the Anti-Socialist Party, and at the election won 26 seats (up two), to Labor on 26 seats (up three). The Deakin government continued with Labor support for the time being, despite only holding 16 seats after losing 10, although with another 5 independent Protectionists.

In 1907-08, Reid strenuously resisted Deakin's commitment to increase tariff rates. In 1908, when Deakin proposed the Commonwealth Liberal Party

Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Commonwealth Liberal Party was a political movement active in Australia from 1909 to 1916, shortly after federation....

, a "Fusion" of the two non-Labor parties, Reid stood aside from the leadership. Joseph Cook

Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook, GCMG was an Australian politician and the sixth Prime Minister of Australia. Born as Joseph Cooke and working in the coal mines of Silverdale, Staffordshire during his early life, he emigrated to Lithgow, New South Wales during the late 1880s, and became General-Secretary of the...

was made leader until the parties merged.

On 24 December 1909 he resigned from Parliament (he was the first Member to have resigned twice), however his seat was left vacant until the 1910 election

Australian federal election, 1910

Federal elections were held in Australia on 13 April 1910. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

. His seat of East Sydney

Division of East Sydney

The Division of East Sydney was anAustralian Electoral Division in New South Wales. The division was created in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It was abolished in 1969. It was named for the suburb of East Sydney. It was located in the inner...

was won by Labor's John West

John West (Australian politician)

John Edward West was an English-born Australian trade unionist and politician, and a key figure in the establishment of the Australian Labor Party.-Early life:...

, in an election which saw Labor win 42 of 75 seats, against the CLP on 31 seats. Labor also won a majority in the Senate.

In 1910, Reid was appointed as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

High Commissioner

Westminster St George's (UK Parliament constituency)

Westminster St George's, originally named St George's, Hanover Square, was a parliamentary constituency in Central London. It returned one Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, elected by the first past the post system of election.-History:The...

as a Unionist

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

candidate, where he acted as a spokesman for the self-governing Dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

s in supporting the war effort. He died suddenly in London in September 1918, aged 73 of cerebral thrombosis, survived by his wife and their two sons and daughter. She had become Dame Flora Reid

Flora Reid

Dame Florence "Flora" Reid GBE was the wife of the Prime Minister of Australia Sir George Reid.-Biodata:...

GBE in 1917. He is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery

Putney Vale Cemetery

Putney Vale Cemetery and Crematorium in London is surrounded by Wimbledon Common and Richmond Park, and is located within forty-seven acres of parkland. The cemetery was opened in 1891 and the crematorium in 1938...

.

Reid's posthumous reputation suffered from the general acceptance of protectionist policies by other parties, as well as from his buffoonish public image. In 1989 W. G. McMinn published George Reid (Melbourne University Press), a serious biography designed to rescue Reid from his reputation as a clownish reactionary and attempt to show his Free Trade policies as having been vindicated by history.

Honours

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

. Reid was also appointed a member of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (1904), a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

(1911) and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

(1916).

In 1969 he was honoured on a postage stamp

Postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post

Australia Post is the trading name of the Australian Government-owned Australian Postal Corporation .-History:...

.

Further reading

- Hughes, Colin AColin HughesColin Anfield Hughes is an Australian academic specializing in electoral politics and government.He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees from Columbia University and his Ph.D from the London School of Economics. In 1966, along with John S...

(1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901-1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.5. ISBN 0 19 550471 2

External links

- Archival records and sources held at the National Archives of Australia

- Audio lecture on the life of George Reid, National Museum of Australia

- Undated photo of George Reid and Mrs. Oliver T. Johnston from Library of Congress collection

|-

|-

|-