Geology of Scotland

Encyclopedia

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

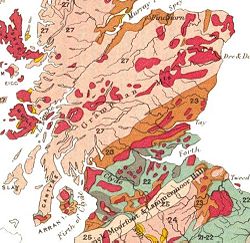

is unusually varied for a country of its size, with a large number of differing geological

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

features. There are three main geographical sub-divisions: the Highlands and Islands

Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands of Scotland are broadly the Scottish Highlands plus Orkney, Shetland and the Hebrides.The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 applied...

is a diverse area which lies to the north and west of the Highland Boundary Fault

Highland Boundary Fault

The Highland Boundary Fault is a geological fault that traverses Scotland from Arran and Helensburgh on the west coast to Stonehaven in the east...

; the Central Lowlands

Central Lowlands

The Central Lowlands or Midland Valley is a geologically defined area of relatively low-lying land in southern Scotland. It consists of a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and the Southern Uplands Fault to the south...

is a rift valley

Rift valley

A rift valley is a linear-shaped lowland between highlands or mountain ranges created by the action of a geologic rift or fault. This action is manifest as crustal extension, a spreading apart of the surface which is subsequently further deepened by the forces of erosion...

mainly comprising Paleozoic

Paleozoic

The Paleozoic era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic eon, spanning from roughly...

formations; and the Southern Uplands

Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas . The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to collectively denote the various ranges of hills within this region...

, which lie south of the Southern Uplands Fault

Southern Uplands Fault

The Southern Uplands Fault is a fault in Scotland that runs from Girvan to Dunbar on the East coast. It marks the southern boundary of the Scottish Midland Valley....

, are largely composed of Silurian

Silurian

The Silurian is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Ordovician Period, about 443.7 ± 1.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Devonian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya . As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period's start and end are well identified, but the...

deposits.

The existing bedrock includes very ancient Archean

Archean

The Archean , also spelled Archeozoic or Archæozoic) is a geologic eon before the Paleoproterozoic Era of the Proterozoic Eon, before 2.5 Ga ago. Instead of being based on stratigraphy, this date is defined chronometrically...

gneiss

Gneiss

Gneiss is a common and widely distributed type of rock formed by high-grade regional metamorphic processes from pre-existing formations that were originally either igneous or sedimentary rocks.-Etymology:...

, metamorphic

Metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rock is the transformation of an existing rock type, the protolith, in a process called metamorphism, which means "change in form". The protolith is subjected to heat and pressure causing profound physical and/or chemical change...

beds interspersed with granite

Granite

Granite is a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Granite usually has a medium- to coarse-grained texture. Occasionally some individual crystals are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic...

intrusions created during the Caledonian mountain building period (the Caledonian orogeny

Caledonian orogeny

The Caledonian orogeny is a mountain building era recorded in the northern parts of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Mountains, Svalbard, eastern Greenland and parts of north-central Europe. The Caledonian orogeny encompasses events that occurred from the Ordovician to Early Devonian, roughly...

), commercially important coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

, oil

Oil

An oil is any substance that is liquid at ambient temperatures and does not mix with water but may mix with other oils and organic solvents. This general definition includes vegetable oils, volatile essential oils, petrochemical oils, and synthetic oils....

and iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

bearing carboniferous

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Devonian Period, about 359.2 ± 2.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Permian Period, about 299.0 ± 0.8 Mya . The name is derived from the Latin word for coal, carbo. Carboniferous means "coal-bearing"...

deposits and the remains of substantial tertiary

Tertiary

The Tertiary is a deprecated term for a geologic period 65 million to 2.6 million years ago. The Tertiary covered the time span between the superseded Secondary period and the Quaternary...

volcano

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

es. During their formation, tectonic movements created climatic conditions ranging from polar to desert to tropical and a resultant diversity of fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

remains.

Scotland has also had a role to play in many significant discoveries such as plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

and the development of theories about the formation of rocks

Petrology

Petrology is the branch of geology that studies rocks, and the conditions in which rocks form....

and was the home of important figures in the development of the science including James Hutton

James Hutton

James Hutton was a Scottish physician, geologist, naturalist, chemical manufacturer and experimental agriculturalist. He is considered the father of modern geology...

, (the "father of modern geology") Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller was a self-taught Scottish geologist and writer, folklorist and an evangelical Christian.- Life and work :Born in Cromarty, he was educated in a parish school where he reportedly showed a love of reading. At 17 he was apprenticed to a stonemason, and his work in quarries, together with...

and Archibald Geikie

Archibald Geikie

Sir Archibald Geikie, OM, KCB, PRS, FRSE , was a Scottish geologist and writer.-Early life:Geikie was born in Edinburgh in 1835, the eldest son of musician and music critic James Stuart Geikie...

. Various locations such as 'Hutton's Unconformity

Hutton's Unconformity

Hutton's Unconformity is any of various famous geological sites in Scotland. These are places identified by 18th-century Scottish geologist James Hutton as an unconformity, which provided evidence for his Plutonist theories of uniformitarianism and about the age of the Earth.-Theory of rock...

' at Siccar Point

Siccar Point

Siccar Point is a rocky promontory in the county of Berwickshire on the east coast of Scotland.It is famous in the history of geology for Hutton's Unconformity found in 1788, which James Hutton regarded as conclusive proof of his uniformitarian theory of geological development.-History:Siccar...

in Berwickshire and the Moine Thrust

Moine Thrust Belt

The Moine Thrust Belt is a linear geological feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast 190 km south-west to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye...

in the north west were also important in the development of geological science.

Overview

_named_(hr).png)

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

and geomorphological

Geomorphology

Geomorphology is the scientific study of landforms and the processes that shape them...

perspective the country has three main sub-divisions all of which were affected by Pleistocene

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene is the epoch from 2,588,000 to 11,700 years BP that spans the world's recent period of repeated glaciations. The name pleistocene is derived from the Greek and ....

glaciations.

Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands lie to the north and west of the Highland Boundary FaultHighland Boundary Fault

The Highland Boundary Fault is a geological fault that traverses Scotland from Arran and Helensburgh on the west coast to Stonehaven in the east...

, which runs from Arran

Isle of Arran

Arran or the Isle of Arran is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, and with an area of is the seventh largest Scottish island. It is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire and the 2001 census had a resident population of 5,058...

to Stonehaven

Stonehaven

Stonehaven is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It lies on Scotland's northeast coast and had a population of 9,577 in 2001 census.Stonehaven, county town of Kincardineshire, grew around an Iron Age fishing village, now the "Auld Toon" , and expanded inland from the seaside...

. This part of Scotland largely comprises ancient rocks, from the Cambrian

Cambrian

The Cambrian is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, lasting from Mya ; it is succeeded by the Ordovician. Its subdivisions, and indeed its base, are somewhat in flux. The period was established by Adam Sedgwick, who named it after Cambria, the Latin name for Wales, where Britain's...

and Precambrian

Precambrian

The Precambrian is the name which describes the large span of time in Earth's history before the current Phanerozoic Eon, and is a Supereon divided into several eons of the geologic time scale...

eras, that were uplifted to form a mountain chain during the later Caledonian orogeny

Orogeny

Orogeny refers to forces and events leading to a severe structural deformation of the Earth's crust due to the engagement of tectonic plates. Response to such engagement results in the formation of long tracts of highly deformed rock called orogens or orogenic belts...

. These foundations are interspersed with many igneous

Igneous rock

Igneous rock is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic rock. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava...

intrusions of a more recent age, the remnants of which have formed mountain massifs such as the Cairngorms

Cairngorms

The Cairngorms are a mountain range in the eastern Highlands of Scotland closely associated with the mountain of the same name - Cairn Gorm.-Name:...

and Skye

Skye

Skye or the Isle of Skye is the largest and most northerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate out from a mountainous centre dominated by the Cuillin hills...

Cuillins. A significant exception to the above are the fossil-bearing beds of Old Red Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is a British rock formation of considerable importance to early paleontology. For convenience the short version of the term, 'ORS' is often used in literature on the subject.-Sedimentology:...

s found principally along the Moray Firth

Moray Firth

The Moray Firth is a roughly triangular inlet of the North Sea, north and east of Inverness, which is in the Highland council area of north of Scotland...

coast and in the Orkney islands. These rocks are around 400 million years old, and were laid down in the Devonian

Devonian

The Devonian is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic Era spanning from the end of the Silurian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya , to the beginning of the Carboniferous Period, about 359.2 ± 2.5 Mya...

period. The Highlands

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

are generally mountainous and are bisected by the Great Glen Fault

Great Glen Fault

The Great Glen Fault is a long strike-slip fault that runs through its namesake the Great Glen in Scotland. However, the fault is actually much longer and over 400 million years old.-Location:...

. The highest elevations in the British Isles

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

are found here, including Ben Nevis

Ben Nevis

Ben Nevis is the highest mountain in the British Isles. It is located at the western end of the Grampian Mountains in the Lochaber area of the Scottish Highlands, close to the town of Fort William....

, the highest peak at 1,344 metres (4,409 ft). Scotland has over 790 islands, divided into four main groups: Shetland

Shetland Islands

Shetland is a subarctic archipelago of Scotland that lies north and east of mainland Great Britain. The islands lie some to the northeast of Orkney and southeast of the Faroe Islands and form part of the division between the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the North Sea to the east. The total...

, Orkney

Orkney Islands

Orkney also known as the Orkney Islands , is an archipelago in northern Scotland, situated north of the coast of Caithness...

, and the Hebrides

Hebrides

The Hebrides comprise a widespread and diverse archipelago off the west coast of Scotland. There are two main groups: the Inner and Outer Hebrides. These islands have a long history of occupation dating back to the Mesolithic and the culture of the residents has been affected by the successive...

, further sub-divided into the Inner Hebrides

Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides is an archipelago off the west coast of Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which enjoy a mild oceanic climate. There are 36 inhabited islands and a further 43 uninhabited Inner Hebrides with an area greater than...

and Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

.

St Kilda, Scotland

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago west-northwest of North Uist in the North Atlantic Ocean. It contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom and three other islands , were also used for...

is composed of Tertiary

Tertiary

The Tertiary is a deprecated term for a geologic period 65 million to 2.6 million years ago. The Tertiary covered the time span between the superseded Secondary period and the Quaternary...

igneous formations of granites and gabbro

Gabbro

Gabbro refers to a large group of dark, coarse-grained, intrusive mafic igneous rocks chemically equivalent to basalt. The rocks are plutonic, formed when molten magma is trapped beneath the Earth's surface and cools into a crystalline mass....

, heavily weathered by the elements. These islands represent the remnants of a long extinct ring volcano rising from a seabed plateau approximately 40 m (130 ft) below sea level.

The geology of Shetland is complex with numerous faults and fold axes. These islands are the northern outpost of the Caledonian orogeny

Caledonian orogeny

The Caledonian orogeny is a mountain building era recorded in the northern parts of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Mountains, Svalbard, eastern Greenland and parts of north-central Europe. The Caledonian orogeny encompasses events that occurred from the Ordovician to Early Devonian, roughly...

and there are outcrops of Lewisian, Dalriadan and Moine metamorphic rocks with similar histories to their equivalents on the Scottish mainland. Similarly, there are also Old Red Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is a British rock formation of considerable importance to early paleontology. For convenience the short version of the term, 'ORS' is often used in literature on the subject.-Sedimentology:...

deposits and granite

Granite

Granite is a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Granite usually has a medium- to coarse-grained texture. Occasionally some individual crystals are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic...

intrusions. The most distinctive feature is the ultrabasic ophiolite

Ophiolites

An ophiolite is a section of the Earth's oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle that has been uplifted and exposed above sea level and often emplaced onto continental crustal rocks...

peridotite

Peridotite

A peridotite is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock, consisting mostly of the minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium, reflecting the high proportions of magnesium-rich olivine, with appreciable iron...

and gabbro

Gabbro

Gabbro refers to a large group of dark, coarse-grained, intrusive mafic igneous rocks chemically equivalent to basalt. The rocks are plutonic, formed when molten magma is trapped beneath the Earth's surface and cools into a crystalline mass....

on Unst

Unst

Unst is one of the North Isles of the Shetland Islands, Scotland. It is the northernmost of the inhabited British Isles and is the third largest island in Shetland after the Mainland and Yell. It has an area of .Unst is largely grassland, with coastal cliffs...

and Fetlar

Fetlar

Fetlar is one of the North Isles of Shetland, Scotland, with a population of 86 at the time of the 2001 census. Its main settlement is Houbie on the south coast, home to the Fetlar Interpretive Centre...

, which are remnants of the Iapetus Ocean

Iapetus Ocean

The Iapetus Ocean was an ocean that existed in the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic eras of the geologic timescale . The Iapetus Ocean was situated in the southern hemisphere, between the paleocontinents of Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia...

floor. Much of Shetland's economy depends on the oil-bearing sediments in the surrounding seas.

Midland Valley

Often referred to as the Central LowlandsCentral Lowlands

The Central Lowlands or Midland Valley is a geologically defined area of relatively low-lying land in southern Scotland. It consists of a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and the Southern Uplands Fault to the south...

, this is a rift valley

Rift valley

A rift valley is a linear-shaped lowland between highlands or mountain ranges created by the action of a geologic rift or fault. This action is manifest as crustal extension, a spreading apart of the surface which is subsequently further deepened by the forces of erosion...

mainly comprising Paleozoic

Paleozoic

The Paleozoic era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic eon, spanning from roughly...

formations. Many of these sediments have economic significance for it is here that the coal and iron bearing rocks that fuelled Scotland's industrial revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

are to be found. This area has also experienced intense vulcanism

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

, Arthur’s Seat

Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh

Arthur's Seat is the main peak of the group of hills which form most of Holyrood Park, described by Robert Louis Stevenson as "a hill for magnitude, a mountain in virtue of its bold design". It is situated in the centre of the city of Edinburgh, about a mile to the east of Edinburgh Castle...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

being the remnant of a once much larger volcano

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

active in the Carboniferous

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Devonian Period, about 359.2 ± 2.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Permian Period, about 299.0 ± 0.8 Mya . The name is derived from the Latin word for coal, carbo. Carboniferous means "coal-bearing"...

period some 300 million years ago. This area is relatively low-lying, although even here hills such as the Ochils

Ochil Hills

The Ochil Hills is a range of hills in Scotland north of the Forth valley bordered by the towns of Stirling, Alloa, Kinross and Perth. The only major roads crossing the hills pass through Glen Devon/Glen Eagles and Glenfarg, the latter now largely replaced except for local traffic by the M90...

and Campsie Fells

Campsie Fells

The Campsie Fells are a range of hills in central Scotland, stretching east to west, from Denny Muir to Dumgoyne, in Stirlingshire. . The highest point in the range is Earl's Seat which is 578 m high...

are rarely far from view.

Southern Uplands

Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas . The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to collectively denote the various ranges of hills within this region...

are a range of hills almost 200 km (124.3 mi) long, interspersed with broad valleys. They lie south of a second fault line running from Ballantrae

Ballantrae

Ballantrae is a community in Carrick, South Ayrshire, Scotland. The name probably comes from the Scottish Gaelic Baile na Tràgha, meaning the "town by the beach"....

towards Dunbar

Dunbar

Dunbar is a town in East Lothian on the southeast coast of Scotland, approximately 28 miles east of Edinburgh and 28 miles from the English Border at Berwick-upon-Tweed....

. The geological foundations largely comprise Silurian

Silurian

The Silurian is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Ordovician Period, about 443.7 ± 1.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Devonian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya . As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period's start and end are well identified, but the...

deposits laid down some 4-500 million years ago.

Post-glacial events

The whole of Scotland was covered by ice sheets during the PleistocenePleistocene

The Pleistocene is the epoch from 2,588,000 to 11,700 years BP that spans the world's recent period of repeated glaciations. The name pleistocene is derived from the Greek and ....

ice ages and the landscape is much affected by glaciation, and to a lesser extent by subsequent sea level changes. In the post-glacial epoch, circa 6100 BC, Scotland and the Faeroe Islands experienced a tsunami

Tsunami

A tsunami is a series of water waves caused by the displacement of a large volume of a body of water, typically an ocean or a large lake...

up to 20 metres high caused by the Storegga Slide

Storegga Slide

The three Storegga Slides are considered to be amongst the largest known landslides. They occurred under water, at the edge of Norway's continental shelf , in the Norwegian Sea, 100 km north-west of the Møre coast, causing a very large tsunami in the North Atlantic Ocean...

s, an immense underwater landslip off the coast of Norway. Earth tremors are infrequent and usually slight. The Great Glen is the most seismically active area of Britain, but the last event of any size was in 1901.

Archean and Proterozoic eons

The oldest rocks of Scotland are the Lewisian gneissesLewisian complex

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian Gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic age, ranging from 3.0–1.7 Ga. They form the basement on which the...

, which were formed in the Precambrian

Precambrian

The Precambrian is the name which describes the large span of time in Earth's history before the current Phanerozoic Eon, and is a Supereon divided into several eons of the geologic time scale...

period, up to 3,000 Ma (million years ago). They are the oldest in Europe and amongst the oldest rocks in the world. They form the basement to the west of the Moine Thrust

Moine Thrust Belt

The Moine Thrust Belt is a linear geological feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast 190 km south-west to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye...

on the mainland, in the Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

and on the islands of Coll

Coll

Coll is a small island, west of Mull in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Coll is known for its sandy beaches, which rise to form large sand dunes, for its corncrakes, and for Breachacha Castle.-Geography and geology:...

and Tiree

Tiree

-History:Tiree is known for the 1st century BC Dùn Mòr broch, for the prehistoric carved Ringing Stone and for the birds of the Ceann a' Mhara headland....

. These rocks are largely igneous in origin, mixed with metamorphosed marble

Marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite.Geologists use the term "marble" to refer to metamorphosed limestone; however stonemasons use the term more broadly to encompass unmetamorphosed limestone.Marble is commonly used for...

, quartzite

Quartzite

Quartzite is a hard metamorphic rock which was originally sandstone. Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tectonic compression within orogenic belts. Pure quartzite is usually white to gray, though quartzites often occur in various shades of pink...

and mica schist and intruded by later basaltic dykes and granite magma. One of these intrusions forms the summit plateau of the mountain Roineabhal

Roineabhal

Roineabhal is a hill on the Isle of Harris, in the Western Isles of Scotland. The granite on the summit plateau of the mountain is anorthosite, and is similar in composition to rocks found in the mountains of the Moon....

in Harris. The granite here is anorthosite

Anorthosite

Anorthosite is a phaneritic, intrusive igneous rock characterized by a predominance of plagioclase feldspar , and a minimal mafic component...

, and is similar in composition to rocks found in the mountains of the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

.

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera....

s muds and lava

Lava

Lava refers both to molten rock expelled by a volcano during an eruption and the resulting rock after solidification and cooling. This molten rock is formed in the interior of some planets, including Earth, and some of their satellites. When first erupted from a volcanic vent, lava is a liquid at...

s were deposited in what is now the Highlands of Scotland

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

.

Cambrian period

Further sedimentary deposits were formed through the CambrianCambrian

The Cambrian is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, lasting from Mya ; it is succeeded by the Ordovician. Its subdivisions, and indeed its base, are somewhat in flux. The period was established by Adam Sedgwick, who named it after Cambria, the Latin name for Wales, where Britain's...

period, (542–488 Ma) some of which, along with the earlier Precambrian sediments, metamorphosed

Metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rock is the transformation of an existing rock type, the protolith, in a process called metamorphism, which means "change in form". The protolith is subjected to heat and pressure causing profound physical and/or chemical change...

into the Dalradian

Dalradian

Dalradian in geology describes a series of metamorphic rocks, typically developed in the high ground which lies southeast of the Great Glen of Scotland...

series. This is composed of a wide variety of materials, including mica schist, biotite

Biotite

Biotite is a common phyllosilicate mineral within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . More generally, it refers to the dark mica series, primarily a solid-solution series between the iron-endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more aluminous endmembers...

gneiss schist, schistose grit, greywacke

Greywacke

Greywacke or Graywacke is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lithic fragments set in a compact, clay-fine matrix. It is a texturally immature sedimentary rock generally found...

and quartzite

Quartzite

Quartzite is a hard metamorphic rock which was originally sandstone. Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tectonic compression within orogenic belts. Pure quartzite is usually white to gray, though quartzites often occur in various shades of pink...

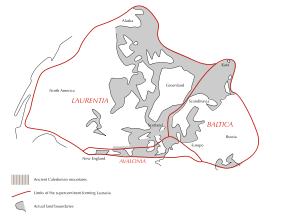

. The area that would become Scotland was at this time close to the south pole and part of Laurentia

Laurentia

Laurentia is a large area of continental craton, which forms the ancient geological core of the North American continent...

. Fossils from the north-west Highlands indicate the presence of trilobite

Trilobite

Trilobites are a well-known fossil group of extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the Atdabanian stage of the Early Cambrian period , and they flourished throughout the lower Paleozoic era before...

s and other primitive forms of life.

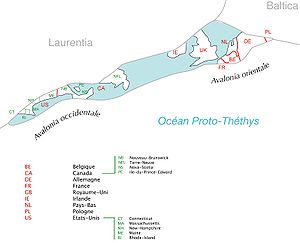

Ordovician period

The proto-Scotland landmass moved northwards and from 460–430 Ma sandstoneSandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

, mudstone

Mudstone

Mudstone is a fine grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Grain size is up to 0.0625 mm with individual grains too small to be distinguished without a microscope. With increased pressure over time the platey clay minerals may become aligned, with the...

and limestone

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera....

was deposited in the area that is now the Midland Valley

Central Lowlands

The Central Lowlands or Midland Valley is a geologically defined area of relatively low-lying land in southern Scotland. It consists of a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and the Southern Uplands Fault to the south...

. This occurred in shallow tropical seas at the margins of the Iapetus Ocean

Iapetus Ocean

The Iapetus Ocean was an ocean that existed in the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic eras of the geologic timescale . The Iapetus Ocean was situated in the southern hemisphere, between the paleocontinents of Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia...

. The Ballantrae Complex near Girvan

Girvan

Girvan is a burgh in Carrick, South Ayrshire, Scotland, with a population of about 8000 people. Originally a fishing port, it is now also a seaside resort with beaches and cliffs. Girvan dates back to 1668 when is became a municipal burgh incorporated by by charter...

was formed from this ocean floor and is similar in composition to rocks found at The Lizard

The Lizard

The Lizard is a peninsula in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The most southerly point of the British mainland is near Lizard Point at ....

in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

. Nonetheless, northern and southern Britain were far apart at the beginning of this period, although the gap began to close as the continent of Avalonia

Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent underlie south-west Great Britain, and the eastern coast of North America. It is the source of many of the older rocks of Western Europe, Atlantic Canada, and parts of the coastal United States...

broke away from Gondwana

Gondwana

In paleogeography, Gondwana , originally Gondwanaland, was the southernmost of two supercontinents that later became parts of the Pangaea supercontinent. It existed from approximately 510 to 180 million years ago . Gondwana is believed to have sutured between ca. 570 and 510 Mya,...

, collided with Baltica

Baltica

Baltica is a name applied by geologists to a late-Proterozoic, early-Palaeozoic continent that now includes the East European craton of northwestern Eurasia. Baltica was created as an entity not earlier than 1.8 billion years ago. Before this time, the three segments/continents that now comprise...

and drifted towards Laurentia. The Caledonian orogeny

Caledonian orogeny

The Caledonian orogeny is a mountain building era recorded in the northern parts of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Mountains, Svalbard, eastern Greenland and parts of north-central Europe. The Caledonian orogeny encompasses events that occurred from the Ordovician to Early Devonian, roughly...

began forming a mountain chain from Norway to the Appalachians. There was an ice age in the southern hemisphere, and the first mass extinction of life on Earth took place at the end of this period.

Silurian period

Silurian

The Silurian is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Ordovician Period, about 443.7 ± 1.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Devonian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya . As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period's start and end are well identified, but the...

period (443–416 Ma) the continent of Laurentia

Laurentia

Laurentia is a large area of continental craton, which forms the ancient geological core of the North American continent...

gradually collided with Baltica, joining Scotland to the area that would become England and Europe. Sea levels rose as the Ordovician

Ordovician

The Ordovician is a geologic period and system, the second of six of the Paleozoic Era, and covers the time between 488.3±1.7 to 443.7±1.5 million years ago . It follows the Cambrian Period and is followed by the Silurian Period...

ice sheets melted, and tectonic movements created major faults which assembled the outline of Scotland from previously scattered fragments. These faults are the Highland Boundary Fault

Highland Boundary Fault

The Highland Boundary Fault is a geological fault that traverses Scotland from Arran and Helensburgh on the west coast to Stonehaven in the east...

, separating the Lowlands from the Highlands, the Great Glen Fault

Great Glen Fault

The Great Glen Fault is a long strike-slip fault that runs through its namesake the Great Glen in Scotland. However, the fault is actually much longer and over 400 million years old.-Location:...

that divides the North-west Highlands from the Grampians, the Southern Uplands Fault and the Iapetus Suture

Iapetus Suture

The Iapetus Suture is one of several major geological faults caused by the collision of several ancient land masses forming a suture. It represents in part the remains of what was once the Iapetus Ocean. Iapetus was the father of Atlas in Greek mythology, making his an appropriate name for what...

, which runs from the Solway Firth

Solway Firth

The Solway Firth is a firth that forms part of the border between England and Scotland, between Cumbria and Dumfries and Galloway. It stretches from St Bees Head, just south of Whitehaven in Cumbria, to the Mull of Galloway, on the western end of Dumfries and Galloway. The Isle of Man is also very...

to Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne is a tidal island off the north-east coast of England. It is also known as Holy Island and constitutes a civil parish in Northumberland...

and which marks the close of the Iapetus Ocean

Iapetus Ocean

The Iapetus Ocean was an ocean that existed in the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic eras of the geologic timescale . The Iapetus Ocean was situated in the southern hemisphere, between the paleocontinents of Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia...

and the joining of northern and southern Britain.

Silurian rocks form the Southern Uplands

Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas . The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to collectively denote the various ranges of hills within this region...

of Scotland, which were pushed up from the sea bed during the collision with Baltica/Avalonia. The majority of the rocks are weakly metamorphosed coarse greywacke

Greywacke

Greywacke or Graywacke is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lithic fragments set in a compact, clay-fine matrix. It is a texturally immature sedimentary rock generally found...

. The Highlands were also affected by these collisions, creating a series of thrust fault

Thrust fault

A thrust fault is a type of fault, or break in the Earth's crust across which there has been relative movement, in which rocks of lower stratigraphic position are pushed up and over higher strata. They are often recognized because they place older rocks above younger...

s in the northwest Highlands including the Moine Thrust

Moine Thrust Belt

The Moine Thrust Belt is a linear geological feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast 190 km south-west to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye...

, the understanding of which played an important role in 19th century geological thinking. Volcanic activity

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

occurred across Scotland as a result of the collision of the tectonic plates, with volcano

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

es in southern Scotland, and magma chamber

Magma chamber

A magma chamber is a large underground pool of molten rock found beneath the surface of the Earth. The molten rock in such a chamber is under great pressure, and given enough time, that pressure can gradually fracture the rock around it creating outlets for the magma...

s in the north, which today form the granite

Granite

Granite is a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Granite usually has a medium- to coarse-grained texture. Occasionally some individual crystals are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic...

mountains such as the Cairngorms

Cairngorms

The Cairngorms are a mountain range in the eastern Highlands of Scotland closely associated with the mountain of the same name - Cairn Gorm.-Name:...

.

Devonian period

Euramerica

Euramerica was a minor supercontinent created in the Devonian as the result of a collision between the Laurentian, Baltica, and Avalonia cratons .300 million years ago in the Late Carboniferous tropical rainforests lay over the equator of Euramerica...

and lay some 25 degrees south

25th parallel south

The 25th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 25 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane, just south of the Tropic of Capricorn...

of the equator, moving slowly north during this period to 10 degrees south

10th parallel south

The 10th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 10 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, Africa, the Indian Ocean, Australasia, the Pacific Ocean and South America....

. The accumulations of Old Red Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is a British rock formation of considerable importance to early paleontology. For convenience the short version of the term, 'ORS' is often used in literature on the subject.-Sedimentology:...

laid down from 408 to 370 million years ago were created as earlier Silurian

Silurian

The Silurian is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Ordovician Period, about 443.7 ± 1.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Devonian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya . As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period's start and end are well identified, but the...

rocks, uplifted by the formation of Pangaea

Pangaea

Pangaea, Pangæa, or Pangea is hypothesized as a supercontinent that existed during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras about 250 million years ago, before the component continents were separated into their current configuration....

, eroded and were deposited into a body of fresh water

Water

Water is a chemical substance with the chemical formula H2O. A water molecule contains one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms connected by covalent bonds. Water is a liquid at ambient conditions, but it often co-exists on Earth with its solid state, ice, and gaseous state . Water also exists in a...

(probably a series of large river deltas). A huge freshwater lake - the Orcadian Lake

Orcadian Lakes

The Orcadian Lakes are a series of lakes which existed during the Devonian period in the region which is now northern Scotland, Orkney and Shetland. The sedimentary rocks they left behind have been studied since the 1830's...

- existed on the edges of the eroding mountains stretching from Shetland to the southern Moray Firth. The formations are extremely thick, up to 11,000 metres in places, and can be subdivided into three categories "Lower", "Middle", and "Upper" from oldest to youngest. As a result, the Old Red Sandstone is an important source of fish fossils and it was the object of intense geological studies in the 19th century. In Scotland these rocks are found predominantly in the Moray Firth basin and Orkney Archipelago, and along the southern margins of the Highland Boundary Fault.

Elsewhere volcanic activity, possibly as a result of the closing of the Iapetus Suture, created the Cheviot Hills

Cheviot Hills

The Cheviot Hills is a range of rolling hills straddling the England–Scotland border between Northumberland and the Scottish Borders.There is a broad split between the northern and the southern Cheviots...

, Ochil Hills

Ochil Hills

The Ochil Hills is a range of hills in Scotland north of the Forth valley bordered by the towns of Stirling, Alloa, Kinross and Perth. The only major roads crossing the hills pass through Glen Devon/Glen Eagles and Glenfarg, the latter now largely replaced except for local traffic by the M90...

, Sidlaw Hills

Sidlaw Hills

The Sidlaws are a range of hills of volcanic origin in the counties of Perthshire and Angus in Scotland that extend for 30 miles from Kinnoull Hill, near Perth, northeast to Forfar. Law is a Lowland Scots word of Old English origin meaning a hill which rises sharply from the surrounding land...

, parts of the Pentland Hills

Pentland Hills

The Pentland Hills are a range of hills to the south-west of Edinburgh, Scotland. The range is around 20 miles in length, and runs south west from Edinburgh towards Biggar and the upper Clydesdale.Some of the peaks include:* Scald Law...

and Scurdie Ness on the Angus

Angus

Angus is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland, a registration county and a lieutenancy area. The council area borders Aberdeenshire, Perth and Kinross and Dundee City...

coast.

Carboniferous period

During the CarboniferousCarboniferous

The Carboniferous is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Devonian Period, about 359.2 ± 2.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Permian Period, about 299.0 ± 0.8 Mya . The name is derived from the Latin word for coal, carbo. Carboniferous means "coal-bearing"...

period (359–299 Ma), Scotland lay close to the equator. Several changes in sea level occurred and the coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

deposits of Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire or the County of Lanark ) is a Lieutenancy area, registration county and former local government county in the central Lowlands of Scotland...

and West Lothian

West Lothian

West Lothian is one of the 32 unitary council areas in Scotland, and a Lieutenancy area. It borders the City of Edinburgh, Falkirk, North Lanarkshire, the Scottish Borders and South Lanarkshire....

and limestones of Fife

Fife

Fife is a council area and former county of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries to Perth and Kinross and Clackmannanshire...

and Dunbar

Dunbar

Dunbar is a town in East Lothian on the southeast coast of Scotland, approximately 28 miles east of Edinburgh and 28 miles from the English Border at Berwick-upon-Tweed....

date from this time. There are oil shales

Oil shale geology

Oil shale geology is a branch of geologic sciences which studies the formation and composition of oil shales–fine-grained sedimentary rocks containing significant amounts of kerogen, and belonging to the group of sapropel fuels. Oil shale formation takes place in a number of depositional...

near Bathgate

Bathgate

Bathgate is a town in West Lothian, Scotland, on the M8 motorway west of Livingston. Nearby towns are Blackburn, Armadale, Whitburn, Livingston, and Linlithgow. Edinburgh Airport is away...

around which the 19th century oil-processing industry developed, and elsewhere in the Midland Valley there are ironstones and fire clay deposits that had significance in the early Industrial Revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

. Fossil Grove

Fossil Grove

The Fossil Grove is located within Victoria Park, Glasgow, Scotland. It was discovered in 1887 and contains the fossilised stumps of eleven extinct Lepidodendron trees, which are sometimes described as "giant club mosses" but they may be more closely related to quillworts...

in Victoria Park, Glasgow

Victoria Park, Glasgow

-Description:Victoria Park is set in western Glasgow, adjacent to the districts of Scotstoun, Whiteinch, Jordanhill and Broomhill. The park was created and named for Queen Victoria's jubilee in 1886. The main entrances to the park are from Westland Drive, Victoria Park Drive North, and Balshagray...

contains the preserved remains of a Carboniferous forest. More volcanic activity formed Arthur's Seat

Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh

Arthur's Seat is the main peak of the group of hills which form most of Holyrood Park, described by Robert Louis Stevenson as "a hill for magnitude, a mountain in virtue of its bold design". It is situated in the centre of the city of Edinburgh, about a mile to the east of Edinburgh Castle...

and the Salisbury Crags in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

and the nearby Bathgate Hills

Bathgate

Bathgate is a town in West Lothian, Scotland, on the M8 motorway west of Livingston. Nearby towns are Blackburn, Armadale, Whitburn, Livingston, and Linlithgow. Edinburgh Airport is away...

.

Permian period

Pangaea

Pangaea, Pangæa, or Pangea is hypothesized as a supercontinent that existed during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras about 250 million years ago, before the component continents were separated into their current configuration....

in the Permian

Permian

The PermianThe term "Permian" was introduced into geology in 1841 by Sir Sir R. I. Murchison, president of the Geological Society of London, who identified typical strata in extensive Russian explorations undertaken with Edouard de Verneuil; Murchison asserted in 1841 that he named his "Permian...

(299–251 Ma), during which proto-Britain continued to drift northwards. Scotland's climate was arid at this time and some fossils of reptiles have been recovered. However, Permian sandstones are found in only a few places - principally in the south west, on the island of Arran, and on the Moray coast. Stone quarried from Hopeman

Hopeman

Hopeman is a seaside village in Moray, Scotland, on the coast of the Moray Firth, founded in 1805 to house and re-employ people displaced during the Highland clearances. The population is around 1 000 people in approximately 670 households.-The village:...

in Moray has been used in the National Museum

National Museum of Scotland

The National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, was formed in 2006 with the merger of the Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, and the Royal Museum next door, with collections covering science and technology, natural history, and world...

and Scottish Parliament building

Scottish Parliament Building

The Scottish Parliament Building is the home of the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, within the UNESCO World Heritage Site in central Edinburgh. Construction of the building commenced in June 1999 and the Members of the Scottish Parliament held their first debate in the new building on 7...

s in Edinburgh.

At the close of this period came the Permian–Triassic extinction event in which 96% of all marine

Marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of organisms in the ocean or other marine or brackish bodies of water. Given that in biology many phyla, families and genera have some species that live in the sea and others that live on land, marine biology classifies species based on the environment rather...

species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

vanished and from which bio-diversity took 30 million years to recover.

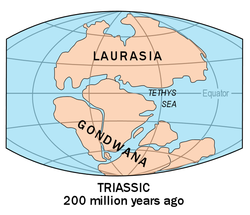

Triassic period

During the TriassicTriassic

The Triassic is a geologic period and system that extends from about 250 to 200 Mya . As the first period of the Mesozoic Era, the Triassic follows the Permian and is followed by the Jurassic. Both the start and end of the Triassic are marked by major extinction events...

, (251–200 Ma) much of Scotland remained in desert conditions, with higher ground in the Highlands and Southern Uplands providing sediment to the surrounding basins via flash floods. This is the origin of sandstone outcrops near Dumfries

Dumfries

Dumfries is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth. Dumfries was the county town of the former county of Dumfriesshire. Dumfries is nicknamed Queen of the South...

, Elgin

Elgin, Moray

Elgin is a former cathedral city and Royal Burgh in Moray, Scotland. It is the administrative and commercial centre for Moray. The town originated to the south of the River Lossie on the higher ground above the flood plain. Elgin is first documented in the Cartulary of Moray in 1190...

and the Isle of Arran

Isle of Arran

Arran or the Isle of Arran is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, and with an area of is the seventh largest Scottish island. It is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire and the 2001 census had a resident population of 5,058...

. Towards the close of this period sea levels began to rise and climatic conditions became less arid.

Jurassic period

Jurassic

The Jurassic is a geologic period and system that extends from about Mya to Mya, that is, from the end of the Triassic to the beginning of the Cretaceous. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of the Mesozoic era, also known as the age of reptiles. The start of the period is marked by...

(200–145 Ma) started, Pangaea

Pangaea

Pangaea, Pangæa, or Pangea is hypothesized as a supercontinent that existed during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras about 250 million years ago, before the component continents were separated into their current configuration....

began to break up into two continents, Gondwana

Gondwana

In paleogeography, Gondwana , originally Gondwanaland, was the southernmost of two supercontinents that later became parts of the Pangaea supercontinent. It existed from approximately 510 to 180 million years ago . Gondwana is believed to have sutured between ca. 570 and 510 Mya,...

and Laurasia

Laurasia

In paleogeography, Laurasia was the northernmost of two supercontinents that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from approximately...

, marking the beginning of the separation of Scotland and North America. Sea levels rose, as Britain and Ireland drifted on the Eurasian Plate

Eurasian Plate

The Eurasian Plate is a tectonic plate which includes most of the continent of Eurasia , with the notable exceptions of the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian subcontinent, and the area east of the Chersky Range in East Siberia...

to between 30° and 40° north. Most of northern and eastern Scotland including Orkney, Shetland and the Outer Hebrides remained above the advancing seas, but the south and south-west were inundated. There are only isolated sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rock are types of rock that are formed by the deposition of material at the Earth's surface and within bodies of water. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause mineral and/or organic particles to settle and accumulate or minerals to precipitate from a solution....

s remaining on land from this period, on the Sutherland

Sutherland

Sutherland is a registration county, lieutenancy area and historic administrative county of Scotland. It is now within the Highland local government area. In Gaelic the area is referred to according to its traditional areas: Dùthaich 'IcAoidh , Asainte , and Cataibh...

coast near Golspie and, forming the Great Estuarine Group

Great Estuarine Group

The Great Estuarine Group is a sequence of rocks which outcrop around the coast of the West Highlands of Scotland. Laid down in the Hebrides Basin during the middle Jurassic, they are the rough time equivalent of the Inferior and Great Oolite Groups found in southern England.This sequence of rocks...

, on Skye, Mull, Raasay

Raasay

Raasay is an island between the Isle of Skye and the mainland of Scotland. It is separated from Skye by the Sound of Raasay and from Applecross by the Inner Sound. It is most famous for being the birthplace of the poet Sorley MacLean, an important figure in the Scottish literary renaissance...

and Eigg

Eigg

Eigg is one of the Small Isles, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is long from north to south, and east to west. With an area of , it is the second largest of the Small Isles after Rùm.-Geography:The main...

. This period does however have considerable significance.

The burial of algae

Algae

Algae are a large and diverse group of simple, typically autotrophic organisms, ranging from unicellular to multicellular forms, such as the giant kelps that grow to 65 meters in length. They are photosynthetic like plants, and "simple" because their tissues are not organized into the many...

and bacteria below the mud of the sea floor during this time resulted in the formation of North Sea oil

North Sea oil

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid oil and natural gas, produced from oil reservoirs beneath the North Sea.In the oil industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian Sea and the area known as "West of Shetland", "the Atlantic Frontier" or "the...

and natural gas

Natural gas

Natural gas is a naturally occurring gas mixture consisting primarily of methane, typically with 0–20% higher hydrocarbons . It is found associated with other hydrocarbon fuel, in coal beds, as methane clathrates, and is an important fuel source and a major feedstock for fertilizers.Most natural...

, much of it trapped in overlying sandstone by deposits formed as the seas fell to form the swamps and salty lakes and lagoons that were home to dinosaur

Dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of animals of the clade and superorder Dinosauria. They were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates for over 160 million years, from the late Triassic period until the end of the Cretaceous , when the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event led to the extinction of...

s.

Cretaceous period

In the CretaceousCretaceous

The Cretaceous , derived from the Latin "creta" , usually abbreviated K for its German translation Kreide , is a geologic period and system from circa to million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the...

, (146–65 Ma) Laurasia split into the continents of North America and Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

. Sea levels rose globally during this period and much of low-lying Scotland was covered in a layer of chalk

Chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous sedimentary rock, a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite. Calcite is calcium carbonate or CaCO3. It forms under reasonably deep marine conditions from the gradual accumulation of minute calcite plates shed from micro-organisms called coccolithophores....

. Although large deposits of Cretaceous

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous , derived from the Latin "creta" , usually abbreviated K for its German translation Kreide , is a geologic period and system from circa to million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the...

rocks were laid down over Scotland, these have not survived erosion except in a few places on the west coast such as Loch Aline

Loch Aline

Loch Aline is a small salt water loch home to fish, birds and game, located in Morvern, Lochaber, Scotland. Key features of interest are Kinlochaline Castle, Ardtornish Castle and the Ardtornish Estate located at its head....

in Morvern

Morvern

Morvern is a peninsula in south west Lochaber, on the west coast of Scotland. The name is derived from the Gaelic A' Mhorbhairne . The highest point is the summit of the Corbett Creach Bheinn which reaches in elevation....

where they form a part of the Inner Hebrides Group

Inner Hebrides Group

In geology, the Inner Hebrides Group is a lithostratigraphical division containing a range of rocks mainly of Upper Cretaceous age which occur around the west coast of the Scottish Highlands...

. At the end of this period the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event brought the age of dinosaurs to a close.

Paleogene period

In the early PaleogenePaleogene

The Paleogene is a geologic period and system that began 65.5 ± 0.3 and ended 23.03 ± 0.05 million years ago and comprises the first part of the Cenozoic Era...

period between 63 and 52 Ma, the last volcanic rocks in the British Isles were formed. As North America and Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

, separated from Europe the Atlantic Ocean slowly formed. This led to a chain of volcanic sites west of mainland Scotland including on Skye, the Small Isles

Small Isles

The Small Isles are a small archipelago of islands in the Inner Hebrides, off the west coast of Scotland. They lie south of Skye and north of Mull and Ardnamurchan – the most westerly point of mainland Scotland.The four main islands are Canna, Rùm, Eigg and Muck...

and St. Kilda

St Kilda, Scotland

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago west-northwest of North Uist in the North Atlantic Ocean. It contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom and three other islands , were also used for...

, in the Firth of Clyde

Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde forms a large area of coastal water, sheltered from the Atlantic Ocean by the Kintyre peninsula which encloses the outer firth in Argyll and Ayrshire, Scotland. The Kilbrannan Sound is a large arm of the Firth of Clyde, separating the Kintyre Peninsula from the Isle of Arran.At...

on Arran

Isle of Arran

Arran or the Isle of Arran is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, and with an area of is the seventh largest Scottish island. It is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire and the 2001 census had a resident population of 5,058...

and Ailsa Craig

Ailsa Craig

Ailsa Craig is an island of 219.69 acres in the outer Firth of Clyde, Scotland where blue hone granite was quarried to make curling stones. "Ailsa" is pronounced "ale-sa", with the first syllable stressed...

and at Ardnamurchan

Ardnamurchan

Ardnamurchan is a peninsula in Lochaber, Highland, Scotland, noted for being very unspoilt and undisturbed. Its remoteness is accentuated by the main access route being a single track road for much of its length.-Geography:...

. Sea levels began to fall, and for the first time the general outline of the modern British Isles was revealed. At the beginning of this period the climate was sub-tropical and erosion was caused by chemical weathering, creating characteristic features of the Scottish landscape such as the topographical basin of the Howe of Alford

Alford, Aberdeenshire

Alford is a large village in Aberdeenshire, north-east Scotland, lying just south of the River Don. It lies within the Howe of Alford which occupies the middle reaches of the River Don....

near Aberdeen. By 35 Ma the landscape included beech

Beech

Beech is a genus of ten species of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia and North America.-Habit:...

, oak

Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus Quercus , of which about 600 species exist. "Oak" may also appear in the names of species in related genera, notably Lithocarpus...

, chestnut

Chestnut

Chestnut , some species called chinkapin or chinquapin, is a genus of eight or nine species of deciduous trees and shrubs in the beech family Fagaceae, native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce.-Species:The chestnut belongs to the...

and sycamore

Sycamore Maple

Acer pseudoplatanus, the sycamore maple, is a species of maple native to central Europe and southwestern Asia, from France east to Ukraine, and south in mountains to northern Spain, northern Turkey, and the Caucasus. It is not related to other trees called sycamore or plane tree in the Platanus...

trees, along with grass

Grass

Grasses, or more technically graminoids, are monocotyledonous, usually herbaceous plants with narrow leaves growing from the base. They include the "true grasses", of the Poaceae family, as well as the sedges and the rushes . The true grasses include cereals, bamboo and the grasses of lawns ...

land.

Miocene and Pliocene epochs

In the Miocene

Miocene

The Miocene is a geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about . The Miocene was named by Sir Charles Lyell. Its name comes from the Greek words and and means "less recent" because it has 18% fewer modern sea invertebrates than the Pliocene. The Miocene follows the Oligocene...

and Pliocene

Pliocene

The Pliocene Epoch is the period in the geologic timescale that extends from 5.332 million to 2.588 million years before present. It is the second and youngest epoch of the Neogene Period in the Cenozoic Era. The Pliocene follows the Miocene Epoch and is followed by the Pleistocene Epoch...

epochs further uplift and erosion occurred in the Highlands. Plant and animal types developed into their modern forms, and by about 2 million years ago the landscape would have been broadly recognisable today, with Scotland lying in its present position on the globe. As the Miocene progressed, temperatures dropped and remained similar to today's.

Pleistocene epoch

Ice age

An ice age or, more precisely, glacial age, is a generic geological period of long-term reduction in the temperature of the Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers...

s shaped the land through glacial erosion, creating u-shaped valleys and depositing boulder clay

Boulder clay

Boulder clay, in geology, is a deposit of clay, often full of boulders, which is formed in and beneath glaciers and ice-sheets wherever they are found, but is in a special sense the typical deposit of the Glacial Period in northern Europe and North America...

s, especially on the western seaboard. The last major incursion of ice peaked about 18,000 years ago, leaving other remnant features such at the granite tors on the Cairngorm Mountain

Cairngorms

The Cairngorms are a mountain range in the eastern Highlands of Scotland closely associated with the mountain of the same name - Cairn Gorm.-Name:...

plateaux.

Holocene epoch

Over the last twelve thousand years the most significant new geological features have been the deposits of peat

Peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation matter or histosol. Peat forms in wetland bogs, moors, muskegs, pocosins, mires, and peat swamp forests. Peat is harvested as an important source of fuel in certain parts of the world...

and the development of coastal alluvium. Post-glacial rises in sea level have been combined with isostatic

Isostasy

Isostasy is a term used in geology to refer to the state of gravitational equilibrium between the earth's lithosphere and asthenosphere such that the tectonic plates "float" at an elevation which depends on their thickness and density. This concept is invoked to explain how different topographic...

rises of the land resulting in a relative fall in sea level in most areas. In some places, such as Culbin in Moray, these changes in relative sea level have created a complex series of shorelines. A rare type of Scottish coastline found largely in the Hebrides

Hebrides

The Hebrides comprise a widespread and diverse archipelago off the west coast of Scotland. There are two main groups: the Inner and Outer Hebrides. These islands have a long history of occupation dating back to the Mesolithic and the culture of the residents has been affected by the successive...

consists of machair

Machair (geography)

The machair refers to a fertile low-lying grassy plain found on some of the north-west coastlines of Ireland and Scotland, in particular the Outer Hebrides...

habitat

Habitat

* Habitat , a place where a species lives and grows*Human habitat, a place where humans live, work or play** Space habitat, a space station intended as a permanent settlement...

, a low lying dune pasture land formed as the sea level dropped leaving a raised beach. In the present day, Scotland continues to move slowly north.

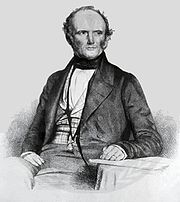

Geologists in Scotland

- James HuttonJames HuttonJames Hutton was a Scottish physician, geologist, naturalist, chemical manufacturer and experimental agriculturalist. He is considered the father of modern geology...

(1726–1797), the "father of modern geology," was born in Edinburgh. His Theory of the Earth, published in 1788 proposed the idea of a rock cycle in which weathered rocks form new sediments and that granites were of volcanic origin. At Glen TiltGlen TiltGlen Tilt is a glen in the extreme north of Perthshire, Scotland. Beginning at the confines of Aberdeenshire, it follows a South-westerly direction excepting for the last 4 miles, when it runs due south to Blair Atholl...

in the CairngormCairngormsThe Cairngorms are a mountain range in the eastern Highlands of Scotland closely associated with the mountain of the same name - Cairn Gorm.-Name:...

mountains he found graniteGraniteGranite is a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Granite usually has a medium- to coarse-grained texture. Occasionally some individual crystals are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic...

penetrating metamorphicMetamorphic rockMetamorphic rock is the transformation of an existing rock type, the protolith, in a process called metamorphism, which means "change in form". The protolith is subjected to heat and pressure causing profound physical and/or chemical change...

schistSchistThe schists constitute a group of medium-grade metamorphic rocks, chiefly notable for the preponderance of lamellar minerals such as micas, chlorite, talc, hornblende, graphite, and others. Quartz often occurs in drawn-out grains to such an extent that a particular form called quartz schist is...

s. This showed to him that granite formed from the cooling of molten rock, not precipitationPrecipitation (chemistry)Precipitation is the formation of a solid in a solution or inside anothersolid during a chemical reaction or by diffusion in a solid. When the reaction occurs in a liquid, the solid formed is called the precipitate, or when compacted by a centrifuge, a pellet. The liquid remaining above the solid...

out of water as the NeptunistsNeptunismNeptunism is a discredited and obsolete scientific theory of geology proposed by Abraham Gottlob Werner in the late 18th century that proposed rocks formed from the crystallisation of minerals in the early Earth's oceans....

of the time believed. This sight is said to have "filled him with delight". Regarding geological time scales he famously remarked "that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end." - John PlayfairJohn PlayfairJohn Playfair FRSE, FRS was a Scottish scientist and mathematician, and a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. He is perhaps best known for his book Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth , which summarized the work of James Hutton...

(1748–1819) from AngusAngusAngus is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland, a registration county and a lieutenancy area. The council area borders Aberdeenshire, Perth and Kinross and Dundee City...

was a mathematician who developed an interest in geology through his friendship with Hutton. His 1802 Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth were influential in the latter's success. - John MacCullochJohn MacCullochJohn MacCulloch FRS was a Scottish geologist.-Biography:MacCulloch, descended from the MacCullochs of Nether Ardwell in Galloway, was born in Guernsey, his mother being a native of that island. Having displayed remarkable powers as a boy, he was sent to study medicine in the university of...

(1773–1835) was born in GuernseyGuernseyGuernsey, officially the Bailiwick of Guernsey is a British Crown dependency in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy.The Bailiwick, as a governing entity, embraces not only all 10 parishes on the Island of Guernsey, but also the islands of Herm, Jethou, Burhou, and Lihou and their islet...

and like Hutton before him, studied medicine at Edinburgh University. A president of the Geological Society from 1815–17, he is best remembered for producing the first geological map of Scotland, published in 1836. 'Macculloch's Tree', a 40 feet (12.2 m) high fossil conifer in the Mull lava flows, is named after him.

- Sir Charles LyellCharles LyellSir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...