Free Trade Hall

Encyclopedia

The Free Trade Hall, Peter Street, Manchester

, was a public hall constructed in 1853–6 on St Peter's Fields, the site of the Peterloo Massacre

and is now a hotel. The hall was built to commemorate the repeal of the Corn Laws

in 1846. The architect was Edward Walters

The hall subsequently was owned by Manchester Corporation, was bombed in the Manchester Blitz and rebuilt. It was Manchester's premier concert venue until the construction of the Bridgewater Hall

in 1996. It was designated a Grade II* listed building on 18 December 1963.

on land given by Richard Cobden

in St Peter's Fields, the site of the Peterloo Massacre. Two earlier halls had been constructed on the site, one, a large timber pavillion built in 1840, and its brick replacement of 1842. The halls were "vital to Manchester's considerable role in the long campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws

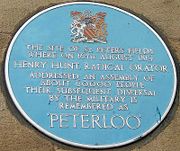

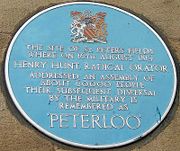

." The hall was funded by public subscription and became a concert hall and home of the Hallé Orchestra in 1858. A blue plaque

records it was built on the site of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819.

It was bought by Manchester Corporation in 1920; but was bombed and left an empty shell in the Manchester Blitz

of December 1940. A new hall was constructed behind the original facade in 1950–51 by Manchester City Council's architect, L.C. Howitt, opening as a concert hall in 1951. As well as housing the Hallé Orchestra, it was used for pop

and rock

concerts. A Wurlitzer

organ from the Paramount Cinema in Manchester was installed over four years and first used in public in a BBC programme in September 1977. When the hall closed the organ, which was on loan to the to the City of Manchester, was moved to the Great Hall in Stockport Town Hall. The Hallé Orchestra moved to the Bridgewater Hall in 1996 and the Tree Trade Hall was closed by the city council.

In 1997, the building was sold by Manchester City Council

to private developers, despite resistance from local groups such as the Manchester Civic Society who viewed the sale as inappropriate given the historical significance of the building and its site. After the initial planning application was refused by the Secretary of State, a second and drastically modified planning application was submitted and approved. Walters' original facade was retained, behind which architects Stephenson Bell

designed the 263-bedroom Radisson Edwardian Hotel; demolishing entirely Howitt's post war hall, although preserving in the main staircase the 1950s statues that were formerly attached to its rear wall. The hotel opened in 2004 at a cost of £45 million.

style hall was built on a trapeziform site in ashlar

sandstone

. It has a two-storey, nine-bay facade

and concealed roof on Peter Street with an arcade

d ground floor with rectangular pier

s with round-headed arches and spandrel

s with the coats of arms

of the Lancashire towns which took part in the Anti-Corn Law movement

. The upper floor has a colonnade

d arcade, its tympana

frieze

is richly decorated with carved figures representing free trade, the arts, commerce, manufacture and the continents. Above the tympanum is a prominent cornice with balustraded parapet

. The upper floor has paired Ionic

column

s to each bay and a tall window with a pediment

ed architrave

behind a balustraded balcony

. The return sides have three bays in a matching but simpler style of blank arches. The rear wall was rebuilt in 1950–51 with pilaster

s surmounted by relief figures representing the entertainment which took place in the old hall. The Large Hall was in a classical style with a coffer

ed ceiling, the walls had wood panelling in oak, walnut and sycamore.

Pevsner

described it as "the noblest monument in the Cinquecento

style in England", whilst Hartwell considered it "a classic which belongs in the canon of historic English architecture."

After its closure, the hall was sold and after a protracted planning process and consultations with English Heritage

it's conversion to a hotel was agreed. During the hotel's construction the Windmill Street and Southmill Street facades were demolished and the north block retained and connected by a triangular glazed atrium

to a new 15-storey block clad in stone and glass. Artifacts salvaged from the old hall, including 1950s statues by Arthur Sherwood Edwards and framed wall plaster autographed by past performers, decorate the atrium light well.

The Free Trade Hall was a venue for public meetings and political speeches and a concert hall. In 1904, Winston Churchill

The Free Trade Hall was a venue for public meetings and political speeches and a concert hall. In 1904, Winston Churchill

delivered a speech at the hall defending Britain's policy of free trade

. The Times called it, "one of the most powerful and brilliant he has made."

In 1905 the Women's Social and Political Union

(WSPU) activists, Christabel Pankhurst

and Annie Kenney

were ejected from a meeting in the hall addressed by the Liberal

politician Sir Edward Grey

, who repeatedly refused to answer their question on Votes for Women

. Christabel Pankhurst immediately began an impromptu meeting outside, and when the police moved them on, contrived to be arrested and brought to court. So began the militant WSPU campaign for the vote.

Kathleen Ferrier

sang at the re-opening of the Free Trade Hall in 1951, ending with a performance of Elgar's Land of Hope and Glory

, the only performance of that piece in her career.

Bob Dylan

played on 17 May 1966, at the height of the controversy

over his perceived betrayal of his folk

roots. Pink Floyd

played there on five occasions: on 16 June 1969 during the Man/Journey tour; on 21 December 1970 during the Atom Heart Mother

tour; on 11 February 1972 during the preview tour for The Dark Side of the Moon

, during which the power failed and the show had to be abandoned – however, the group returned on 29 and 30 March. Genesis

recorded a portion of its first live album, Genesis Live

, there in February 1973.

On 4 June 1976, the Lesser Free Trade Hall was the venue for a concert by the Sex Pistols

attended by 40 people which became legendary as a catalyst to the punk rock

movement and New Wave

. A second concert there was attended by many more people on 20 July 1976.

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

, was a public hall constructed in 1853–6 on St Peter's Fields, the site of the Peterloo Massacre

Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre occurred at St Peter's Field, Manchester, England, on 16 August 1819, when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 that had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation....

and is now a hotel. The hall was built to commemorate the repeal of the Corn Laws

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were trade barriers designed to protect cereal producers in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports between 1815 and 1846. The barriers were introduced by the Importation Act 1815 and repealed by the Importation Act 1846...

in 1846. The architect was Edward Walters

Edward Walters

Edward Walters was an English architect. After superintending Sir John Rennie's military building work in Constantinople between 1832 and 1837, he returned to England to practise as an architect in the provinces...

The hall subsequently was owned by Manchester Corporation, was bombed in the Manchester Blitz and rebuilt. It was Manchester's premier concert venue until the construction of the Bridgewater Hall

Bridgewater Hall

The Bridgewater Hall is an international concert venue in Manchester city centre, England. It cost around £42 million to build and currently hosts over 250 performances a year....

in 1996. It was designated a Grade II* listed building on 18 December 1963.

History

The Free Trade Hall was built as a public hall between 1853 and 1856 by Edward WaltersEdward Walters

Edward Walters was an English architect. After superintending Sir John Rennie's military building work in Constantinople between 1832 and 1837, he returned to England to practise as an architect in the provinces...

on land given by Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden was a British manufacturer and Radical and Liberal statesman, associated with John Bright in the formation of the Anti-Corn Law League as well as with the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty...

in St Peter's Fields, the site of the Peterloo Massacre. Two earlier halls had been constructed on the site, one, a large timber pavillion built in 1840, and its brick replacement of 1842. The halls were "vital to Manchester's considerable role in the long campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were trade barriers designed to protect cereal producers in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports between 1815 and 1846. The barriers were introduced by the Importation Act 1815 and repealed by the Importation Act 1846...

." The hall was funded by public subscription and became a concert hall and home of the Hallé Orchestra in 1858. A blue plaque

Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event, serving as a historical marker....

records it was built on the site of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819.

It was bought by Manchester Corporation in 1920; but was bombed and left an empty shell in the Manchester Blitz

Manchester Blitz

The Manchester Blitz was the heavy bombing of the city of Manchester and its surrounding areas in North West England during the Second World War by the Nazi German Luftwaffe...

of December 1940. A new hall was constructed behind the original facade in 1950–51 by Manchester City Council's architect, L.C. Howitt, opening as a concert hall in 1951. As well as housing the Hallé Orchestra, it was used for pop

Pop music

Pop music is usually understood to be commercially recorded music, often oriented toward a youth market, usually consisting of relatively short, simple songs utilizing technological innovations to produce new variations on existing themes.- Definitions :David Hatch and Stephen Millward define pop...

and rock

Rock music

Rock music is a genre of popular music that developed during and after the 1960s, particularly in the United Kingdom and the United States. It has its roots in 1940s and 1950s rock and roll, itself heavily influenced by rhythm and blues and country music...

concerts. A Wurlitzer

Wurlitzer

The Rudolph Wurlitzer Company, usually referred to simply as Wurlitzer, was an American company that produced stringed instruments, woodwinds, brass instruments, theatre organs, band organs, orchestrions, electronic organs, electric pianos and jukeboxes....

organ from the Paramount Cinema in Manchester was installed over four years and first used in public in a BBC programme in September 1977. When the hall closed the organ, which was on loan to the to the City of Manchester, was moved to the Great Hall in Stockport Town Hall. The Hallé Orchestra moved to the Bridgewater Hall in 1996 and the Tree Trade Hall was closed by the city council.

In 1997, the building was sold by Manchester City Council

Manchester City Council

Manchester City Council is the local government authority for Manchester, a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. It is composed of 96 councillors, three for each of the 32 electoral wards of Manchester. Currently the council is controlled by the Labour Party and is led by...

to private developers, despite resistance from local groups such as the Manchester Civic Society who viewed the sale as inappropriate given the historical significance of the building and its site. After the initial planning application was refused by the Secretary of State, a second and drastically modified planning application was submitted and approved. Walters' original facade was retained, behind which architects Stephenson Bell

Roger Stephenson

Roger Stephenson OBE is an acclaimed English architect and one of the partners of Stephenson Bell Architects in Manchester, England.-Background:Stephenson studied architecture at the Liverpool University School of Architecture...

designed the 263-bedroom Radisson Edwardian Hotel; demolishing entirely Howitt's post war hall, although preserving in the main staircase the 1950s statues that were formerly attached to its rear wall. The hotel opened in 2004 at a cost of £45 million.

Architecture

The Italian palazzoPalazzo

Palazzo, an Italian word meaning a large building , may refer to:-Buildings:*Palazzo, an Italian type of building**Palazzo style architecture, imitative of Italian palazzi...

style hall was built on a trapeziform site in ashlar

Ashlar

Ashlar is prepared stone work of any type of stone. Masonry using such stones laid in parallel courses is known as ashlar masonry, whereas masonry using irregularly shaped stones is known as rubble masonry. Ashlar blocks are rectangular cuboid blocks that are masonry sculpted to have square edges...

sandstone

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

. It has a two-storey, nine-bay facade

Facade

A facade or façade is generally one exterior side of a building, usually, but not always, the front. The word comes from the French language, literally meaning "frontage" or "face"....

and concealed roof on Peter Street with an arcade

Arcade

Arcade may refer to:*Arcade , a passage or walkway, often including retailers*Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade game's hardware*Arcade game, a coin operated game machine usually found in a game or video arcade...

d ground floor with rectangular pier

Pier

A pier is a raised structure, including bridge and building supports and walkways, over water, typically supported by widely spread piles or pillars...

s with round-headed arches and spandrel

Spandrel

A spandrel, less often spandril or splaundrel, is the space between two arches or between an arch and a rectangular enclosure....

s with the coats of arms

Coat of arms

A coat of arms is a unique heraldic design on a shield or escutcheon or on a surcoat or tabard used to cover and protect armour and to identify the wearer. Thus the term is often stated as "coat-armour", because it was anciently displayed on the front of a coat of cloth...

of the Lancashire towns which took part in the Anti-Corn Law movement

Anti-Corn Law League

The Anti-Corn Law League was in effect the resumption of the Anti-Corn Law Association, which had been created in London in 1836 but did not obtain widespread popularity. The Anti-Corn Law League was founded in Manchester in 1838...

. The upper floor has a colonnade

Colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade denotes a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building....

d arcade, its tympana

Tympanum (architecture)

In architecture, a tympanum is the semi-circular or triangular decorative wall surface over an entrance, bounded by a lintel and arch. It often contains sculpture or other imagery or ornaments. Most architectural styles include this element....

frieze

Frieze

thumb|267px|Frieze of the [[Tower of the Winds]], AthensIn architecture the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Even when neither columns nor pilasters are expressed, on an astylar wall it lies upon...

is richly decorated with carved figures representing free trade, the arts, commerce, manufacture and the continents. Above the tympanum is a prominent cornice with balustraded parapet

Parapet

A parapet is a wall-like barrier at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony or other structure. Where extending above a roof, it may simply be the portion of an exterior wall that continues above the line of the roof surface, or may be a continuation of a vertical feature beneath the roof such as a...

. The upper floor has paired Ionic

Ionic order

The Ionic order forms one of the three orders or organizational systems of classical architecture, the other two canonic orders being the Doric and the Corinthian...

column

Column

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a vertical structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. For the purpose of wind or earthquake engineering, columns may be designed to resist lateral forces...

s to each bay and a tall window with a pediment

Pediment

A pediment is a classical architectural element consisting of the triangular section found above the horizontal structure , typically supported by columns. The gable end of the pediment is surrounded by the cornice moulding...

ed architrave

Architrave

An architrave is the lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of the columns. It is an architectural element in Classical architecture.-Classical architecture:...

behind a balustraded balcony

Balcony

Balcony , a platform projecting from the wall of a building, supported by columns or console brackets, and enclosed with a balustrade.-Types:The traditional Maltese balcony is a wooden closed balcony projecting from a...

. The return sides have three bays in a matching but simpler style of blank arches. The rear wall was rebuilt in 1950–51 with pilaster

Pilaster

A pilaster is a slightly-projecting column built into or applied to the face of a wall. Most commonly flattened or rectangular in form, pilasters can also take a half-round form or the shape of any type of column, including tortile....

s surmounted by relief figures representing the entertainment which took place in the old hall. The Large Hall was in a classical style with a coffer

Coffer

A coffer in architecture, is a sunken panel in the shape of a square, rectangle, or octagon in a ceiling, soffit or vault...

ed ceiling, the walls had wood panelling in oak, walnut and sycamore.

Pevsner

Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner, CBE, FBA was a German-born British scholar of history of art and, especially, of history of architecture...

described it as "the noblest monument in the Cinquecento

Cinquecento

Cinquecento is a term used to describe the Italian Renaissance of the 16th century, including the current styles of art, music, literature, and architecture.-Art:...

style in England", whilst Hartwell considered it "a classic which belongs in the canon of historic English architecture."

After its closure, the hall was sold and after a protracted planning process and consultations with English Heritage

English Heritage

English Heritage . is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport...

it's conversion to a hotel was agreed. During the hotel's construction the Windmill Street and Southmill Street facades were demolished and the north block retained and connected by a triangular glazed atrium

Atrium

Atrium may refer to:*Atrium , a large open space within a building usually with a glass roof*Atrium , microscopic air sacs in lungs*Atrium , an anatomical structure of the heart* Atrium of the ventricular system of the brain...

to a new 15-storey block clad in stone and glass. Artifacts salvaged from the old hall, including 1950s statues by Arthur Sherwood Edwards and framed wall plaster autographed by past performers, decorate the atrium light well.

Events

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

delivered a speech at the hall defending Britain's policy of free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

. The Times called it, "one of the most powerful and brilliant he has made."

In 1905 the Women's Social and Political Union

Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union was the leading militant organisation campaigning for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom...

(WSPU) activists, Christabel Pankhurst

Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, DBE , was a suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union , she directed its militant actions from exile in France from 1912 to 1913. In 1914 she became a fervent supporter of the war against Germany...

and Annie Kenney

Annie Kenney

Annie Kenney was an English working class suffragette who became a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union...

were ejected from a meeting in the hall addressed by the Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

politician Sir Edward Grey

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon KG, PC, FZL, DL , better known as Sir Edward Grey, Bt, was a British Liberal statesman. He served as Foreign Secretary from 1905 to 1916, the longest continuous tenure of any person in that office...

, who repeatedly refused to answer their question on Votes for Women

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

. Christabel Pankhurst immediately began an impromptu meeting outside, and when the police moved them on, contrived to be arrested and brought to court. So began the militant WSPU campaign for the vote.

Kathleen Ferrier

Kathleen Ferrier

Kathleen Mary Ferrier CBE was an English contralto who achieved an international reputation as a stage, concert and recording artist, with a repertoire extending from folksong and popular ballads to the classical works of Bach, Brahms, Mahler and Elgar...

sang at the re-opening of the Free Trade Hall in 1951, ending with a performance of Elgar's Land of Hope and Glory

Land of Hope and Glory

"Land of Hope and Glory" is a British patriotic song, with music by Edward Elgar and lyrics by A. C. Benson, written in 1902.- Composition :...

, the only performance of that piece in her career.

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan is an American singer-songwriter, musician, poet, film director and painter. He has been a major and profoundly influential figure in popular music and culture for five decades. Much of his most celebrated work dates from the 1960s when he was an informal chronicler and a seemingly...

played on 17 May 1966, at the height of the controversy

Electric Dylan controversy

By 1965, Bob Dylan had achieved the status of leading songwriter of the American folk music revival.Paul Simon suggested that Dylan's early compositions virtually took over the folk genre: "[Dylan's] early songs were very rich ... with strong melodies. 'Blowin' in the Wind' has a really strong...

over his perceived betrayal of his folk

Folk music

Folk music is an English term encompassing both traditional folk music and contemporary folk music. The term originated in the 19th century. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted by mouth, as music of the lower classes, and as music with unknown composers....

roots. Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd were an English rock band that achieved worldwide success with their progressive and psychedelic rock music. Their work is marked by the use of philosophical lyrics, sonic experimentation, innovative album art, and elaborate live shows. Pink Floyd are one of the most commercially...

played there on five occasions: on 16 June 1969 during the Man/Journey tour; on 21 December 1970 during the Atom Heart Mother

Atom Heart Mother

Atom Heart Mother is the fifth studio album by English progressive rock band Pink Floyd, released in 1970 by Harvest and EMI Records in the United Kingdom and Harvest and Capitol in the United States. It was recorded at Abbey Road Studios, London, England, and reached number one in the United...

tour; on 11 February 1972 during the preview tour for The Dark Side of the Moon

The Dark Side of the Moon

The Dark Side of the Moon is the eighth studio album by English progressive rock band Pink Floyd, released in March 1973. It built on ideas explored in the band's earlier recordings and live shows, but lacks the extended instrumental excursions that characterised their work following the departure...

, during which the power failed and the show had to be abandoned – however, the group returned on 29 and 30 March. Genesis

Genesis (band)

Genesis are an English rock band that formed in 1967. The band currently comprises the longest-tenured members Tony Banks , Mike Rutherford and Phil Collins . Past members Peter Gabriel , Steve Hackett and Anthony Phillips , also played major roles in the band in its early years...

recorded a portion of its first live album, Genesis Live

Genesis Live

Genesis Live is the first live album released by rock group Genesis in 1973. It was the band's first top 10 hit in the UK reaching No.9 and remaining on the charts for 10 weeks.-History:...

, there in February 1973.

On 4 June 1976, the Lesser Free Trade Hall was the venue for a concert by the Sex Pistols

Sex Pistols

The Sex Pistols were an English punk rock band that formed in London in 1975. They were responsible for initiating the punk movement in the United Kingdom and inspiring many later punk and alternative rock musicians...

attended by 40 people which became legendary as a catalyst to the punk rock

Punk rock

Punk rock is a rock music genre that developed between 1974 and 1976 in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Rooted in garage rock and other forms of what is now known as protopunk music, punk rock bands eschewed perceived excesses of mainstream 1970s rock...

movement and New Wave

New Wave music

New Wave is a subgenre of :rock music that emerged in the mid to late 1970s alongside punk rock. The term at first generally was synonymous with punk rock before being considered a genre in its own right that incorporated aspects of electronic and experimental music, mod subculture, disco and 1960s...

. A second concert there was attended by many more people on 20 July 1976.