Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke

Encyclopedia

Admiral of the Fleet

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke KB

, PC (21 February 1705 – 16 October 1781) was an officer of the Royal Navy

. He is best remembered for his service during the Seven Years' War

, particularly his victory over a French fleet at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

in 1759, preventing a French invasion of Britain

. A number of Royal Navy warships were named after him, in commemoration of this. He had also won an earlier victory, the Battle of Cape Finisterre in 1747 which made his name. Hawke acquired a reputation as a "fighting officer" which allowed his career to prosper, despite him possessing a number of political enemies. He developed the concept of a Western Squadron, keeping an almost continuous blockade of the French coast throughout the war.

Hawke also served as First Lord of the Admiralty for five years between 1766 and 1771. In this post, he oversaw the mobilisation of the British navy during the 1770 Falklands Crisis

.

in 1705, the only son of a lawyer

. His uncle on his mother's side was Colonel Martin Bladen a Member of Parliament

. Hawke joined the navy in 1720, as a Midshipman

. In 1725 he passed his examination as a Lieutenant

, but it was 1729 before he could find a position on a ship because of a shortage of active commands in peace time. After this, his career accelerated and he had received promotion to Captain

by 1734. The following year he went on half-pay

and did not go to sea again until 1739 and the outbreak of the War of Jenkins Ear. He was then recalled and sent to cruise in the Caribbean

with orders to escort British merchant ships. He did this successfully, although it meant his ship did not take part in the British attack on Porto Bello

In 1737 he married a wealthy woman, Catherine Brooke, whose money supported him throughout the remainder of his life.

Hawke did not see action until the Battle of Toulon in 1744 during the War of the Austrian Succession

Hawke did not see action until the Battle of Toulon in 1744 during the War of the Austrian Succession

. The fight at Toulon was extremely confused, although Hawke had emerged from it with a degree of credit. While not a defeat for the British, they had failed to take an opportunity to comprehensively defeat the Franco-Spanish fleet when a number of British ships had not engaged the enemy, leading to a mass court martial. Hawke's ship managed to capture the only prize of the battle, the Spanish ship Poder, although it was subsequently destroyed by the French. Hawke was largely spared the recriminations that followed the battle, that led to the eventual dismissal of the British commander Thomas Mathews

from the navy.

in 1747 and replaced Admiral Peter Warren as the commander of the Western Squadron the same year. Hawke then put a great deal of effort into improving the performance of his crews and instilling in them a sense of pride and patriotism

. The Western Squadron had been established to keep a watch on the French Channel ports. Under a previous commander, Lord Anson, it had successfully contained the French coast and in May 1747 won the First Battle of Cape Finisterre when it attacked a large convoy leaving harbour.

The British had received word that there was now an incoming convoy arriving from the West Indies. Hawke took his fleet and lay in wait for the arrival of the French. In October 1747, Hawke captured six ships of a French squadron in the Bay of Biscay

in the second Battle of Cape Finisterre

. The consequence of this, along with Anson's earlier victory, was to give the British almost total control in the English Channel

during the final months of the war. It proved ruinous to the French economy, helping the British to secure an acceptable peace at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

, despite the recent French conquest of the Austrian Netherlands. In recognition of his victory, Hawke was made a baronet

.

for the naval town of Portsmouth

, which he was to represent for the next thirty years. As one of the most celebrated Admirals of the recent war, Hawke was able to secure a command in the peace-time navy – and he was almost entirely at sea between 1748 and 1752.

He was not on good terms with the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Anson, although they shared similar views on how any future naval war against France should be waged. In spite of their personal disagreements, Anson had a deep respect for Hawke as an Admiral, and pushed unsuccessfully for him to be given a place on the Admiralty board.

He was not on good terms with the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Anson, although they shared similar views on how any future naval war against France should be waged. In spite of their personal disagreements, Anson had a deep respect for Hawke as an Admiral, and pushed unsuccessfully for him to be given a place on the Admiralty board.

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was considered by many merely to be an extended armistice and it was widely anticipated that a return to war was likely. Britain and France clashed over control of the Ohio Country

and this colonial conflict escalated throughout 1754. Under Anson's direction, the British navy again began preparing for war.

By early 1756, after repeated clashes in North America

, and deteriorating relations in Europe, the two sides were formally at war.

as commander in the Mediterranean in 1756. Byng had been unable to relieve Minorca

following the Battle of Minorca

and he was sent back to Britain where he was tried and executed. Almost as soon as Minorca had fallen in June 1756, the French fleet had withdrawn to Toulon in case they were attacked by Hawke. Once he arrived off Minorca, Hawke found that the island had surrendered and there was little he could do to reverse this. He decided not to land the troops he had brought with him from Gibraltar

.

Hawke then spent three months cruising off Minorca

and Marseille

before returning home where he gave evidence against Byng. He was subsequently criticised by some supporters of Byng, for not having blockaded either Minorca or Toulon.

in 1757 and towards the end of the year he was selected to command a naval escort that would land a large force on the coast of France. The plan was to raid a town to hurt the French war effort, and force them to use troops to protect their own coastline, rather than sending them to Germany to attack Prussia

or Hanover

. Hawke, like many of the Generals, was extremely sceptical of the value of such a landing. The expedition was late setting off, further reducing its chances of success.

The expedition arrived off the coast of Rochefort in November. After storming the offshore island of Île-d'Aix

, the army commander Sir John Mordaunt

hesitated before proceeding with the landing on the mainland. Despite a report by Colonel James Wolfe

that they would be able to capture Rochefort, Mordaunt was reluctant to attack.

Hawke then offered an ultimatum - either the Generals attacked immediately or he would sail for home. His fleet was needed to protect an inbound convoy from the West Indies, and could not afford to sit indefinitely off Rochefort. Mourdaunt hastily agreed, and the expedition returned to Britain without having made any serious attempt on the town. There was a later court of inquiry, but both Hawke and Mordaunt were cleared of any blame, and it was concluded that the conception of the attack of Rochefort had been an error. Despite this similar descents were launched the following year against Cherbourg and St Malo. For Hawke, the failure at Rochefort was a disappointment, and he remained sensitive about the issue for many years.

to power, began to change things as he pushed a new strategy which involved expeditions against French colonies in Canada, Africa and the West Indies. Despite the failure of Rochefort, Pitt pushed for fresh landings on the French coast, believing they would be a useful distraction - preventing the French from sending troops to Germany or to the relief of their colonies around the globe.

In 1758 Hawke directed the blockade of Brest

for six months. In 1758 he was involved in a major altercation with his superiors at the Admiralty which saw him strike his flag and return to port over a misunderstanding at which he took offence. Although he later apologised, he was severely reprimanded. He was taken out of active service, but was later restored to command because the cabinet respected his talents of seamanship. In his absence a raid on St Malo had ended badly with the Battle of St Cast, which had seen a British force defeated and captured - bringing an end to the policy of descents, although it was now to be replaced with a far tighter blockade. In Hawke's absence the Channel Fleet had been under the command of Lord Anson.

In 1759 Hawke was tasked with stopping a planned French invasion fleet

In 1759 Hawke was tasked with stopping a planned French invasion fleet

from reaching Britain. A French army was assembled in Brittany

, with plans to combine the separate French fleets so they could seize control of the English Channel

and allow the invasion force to cross and capture London. Hawke's orders were to prevent the large French fleets at Brest and Toulon from joining together. His ships continued their close blockade of Brest.

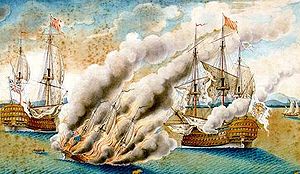

When Hawke's force was driven off station by a storm, the French fleet under Hubert de Brienne, Comte de Conflans

, took advantage and left port. On 20 November 1759 he followed the French warships and during a gale he won a sufficient victory in the Battle of Quiberon Bay

, when combined with Edward Boscawen

's victory at Lagos, to remove the French invasion threat.

Although he had effectively put the French channel fleet out of action for the remainder of the war, Hawke was disappointed he had not secured a more comprehensive victory asserting that had he had two more hours of daylight the whole enemy fleet would have been taken. He occupied the île Dumet and returned home.

. In spite of this the French continued to entertain hopes of a future invasion for the remainder of the war, which drove the British to keep a tight blockade on the French coast. This continued to starve French ports of commerce, further weakening France's economy. After a spell in England, Hawke returned to take command of the blockading fleet off Brest. The British were now effectively mounting a blockade of the French coast from Dunkirk to Marsielles. Hawke attempted to try and destroy some of the remaining French warships, which he had trapped in the Villaine Estuary. He sent in fireships but these failed to accomplish the task. Hawke developed a plan for landing on the coast, seizing a peninsular, and attacking the ships from land. However he was forced to abandon this when orders reached him from Pitt for a much larger expedition.

In an effort to further undermine the French, Pitt had conceived the idea of seizing the island of Belle Île

In an effort to further undermine the French, Pitt had conceived the idea of seizing the island of Belle Île

, off the coast of Brittany

and asked the navy to prepare for an expedition to take it. Hawke made his opposition clear in a letter to Anson, which was subsequently widely circulated. Pitt was extremely annoyed by this, considering that Hawke had overstepped his authority. Nonetheless Pitt pressed ahead with the expedition against Belle Île. An initial assault in April 1761 was repulsed with heavy loss but, reinforced, the British successfully captured the island in June.

Although the capture of the island provided another victory for Pitt, and lowered the morale of the French public by showing that the British could now occupy parts of Metropolitan France

– Hawke’s criticisms of its strategic usefulness were borne out. It was not a useful staging point for further raids on the coast and the French were not especially concerned about its loss, telling Britain during subsequent peace negotiations that they would offer nothing to exchange for it and Britain could keep it if they wished. Britain soon sent much of the garrison of the island to Martinique

and Portugal

to take part in other operations.

He then retired from active duty, and given the honorary rank of Vice-Admiral of Great Britain in November 1765. He was made First Lord of the Admiralty in December 1766. His appointment was due to his expertise on naval matters, as he did little to enhance the government politically. Hawke held this post until January 1771, shortly after the Falklands Crisis

He then retired from active duty, and given the honorary rank of Vice-Admiral of Great Britain in November 1765. He was made First Lord of the Admiralty in December 1766. His appointment was due to his expertise on naval matters, as he did little to enhance the government politically. Hawke held this post until January 1771, shortly after the Falklands Crisis

. He was succeeded by Lord Sandwich

. He was appointed to the Privy Council in 1766.

House, near Southampton, although he died in Sunbury-on-Thames

. His memorial, depicting the Battle of Quiberon Bay, is in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

near Swaythling. He was succeeded in his title by his son Martin Hawke, 2nd Baron Hawke

.

Hawke is referred to in Robert Louis Stevenson

Hawke is referred to in Robert Louis Stevenson

story of Long John Silver

, who claims to have served under Hawke. Another character calls the admiral "the immortal Hawke".

Organisations adopting the Hawke title:

He lends his name to a boarding house at The Royal Hospital School

Many English public houses bear the name 'Admiral Hawke' in his honour.

|-

|-

|-

|-

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy)

Admiral of the fleet is the highest rank of the British Royal Navy and other navies, which equates to the NATO rank code OF-10. The rank still exists in the Royal Navy but routine appointments ceased in 1996....

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke KB

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, PC (21 February 1705 – 16 October 1781) was an officer of the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. He is best remembered for his service during the Seven Years' War

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

, particularly his victory over a French fleet at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

Battle of Quiberon Bay

The naval Battle of Quiberon Bay took place on 20 November 1759 during the Seven Years' War in Quiberon Bay, off the coast of France near St. Nazaire...

in 1759, preventing a French invasion of Britain

Planned French Invasion of Britain (1759)

A French invasion of Great Britain was planned to take place in 1759 during the Seven Years' War, but due to various factors including naval defeats at the Battle of Lagos and the Battle of Quiberon Bay was never launched. The French planned to land 100,000 French soldiers in Britain to end British...

. A number of Royal Navy warships were named after him, in commemoration of this. He had also won an earlier victory, the Battle of Cape Finisterre in 1747 which made his name. Hawke acquired a reputation as a "fighting officer" which allowed his career to prosper, despite him possessing a number of political enemies. He developed the concept of a Western Squadron, keeping an almost continuous blockade of the French coast throughout the war.

Hawke also served as First Lord of the Admiralty for five years between 1766 and 1771. In this post, he oversaw the mobilisation of the British navy during the 1770 Falklands Crisis

Falklands Crisis (1770)

The Falklands Crisis of 1770 was a diplomatic standoff between Britain and Spain over possession of the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. These events were nearly the cause of a war between France, Spain and Britain — the countries poised to dispatch armed fleets to contest the barren...

.

Early life

Hawke was born in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 1705, the only son of a lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

. His uncle on his mother's side was Colonel Martin Bladen a Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

. Hawke joined the navy in 1720, as a Midshipman

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer cadet, or a commissioned officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Kenya...

. In 1725 he passed his examination as a Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

, but it was 1729 before he could find a position on a ship because of a shortage of active commands in peace time. After this, his career accelerated and he had received promotion to Captain

Captain (naval)

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The NATO rank code is OF-5, equivalent to an army full colonel....

by 1734. The following year he went on half-pay

Half-pay

In the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, half-pay referred to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service....

and did not go to sea again until 1739 and the outbreak of the War of Jenkins Ear. He was then recalled and sent to cruise in the Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

with orders to escort British merchant ships. He did this successfully, although it meant his ship did not take part in the British attack on Porto Bello

Battle of Porto Bello

The Battle of Porto Bello, or the Battle of Portobello, was a 1739 battle between a British naval force aiming to capture the settlement of Portobello in Panama, and its Spanish defenders. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, in the early stages of the war sometimes known as the...

In 1737 he married a wealthy woman, Catherine Brooke, whose money supported him throughout the remainder of his life.

Battle of Toulon

War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession – including King George's War in North America, the Anglo-Spanish War of Jenkins' Ear, and two of the three Silesian wars – involved most of the powers of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.The...

. The fight at Toulon was extremely confused, although Hawke had emerged from it with a degree of credit. While not a defeat for the British, they had failed to take an opportunity to comprehensively defeat the Franco-Spanish fleet when a number of British ships had not engaged the enemy, leading to a mass court martial. Hawke's ship managed to capture the only prize of the battle, the Spanish ship Poder, although it was subsequently destroyed by the French. Hawke was largely spared the recriminations that followed the battle, that led to the eventual dismissal of the British commander Thomas Mathews

Thomas Mathews

Thomas Mathews was a British officer of the Royal Navy, who rose to the rank of admiral.Mathews joined the navy in 1690 and saw service on a number of ships, including during the Nine Years' War and the War of the Spanish Succession. He interspersed periods spent commanding ships with time at home...

from the navy.

Battle of Cape Finisterre

Despite having distinguished himself at Toulon, Hawke had little opportunities over the next three years. However, he was promoted to Rear AdmiralRear Admiral

Rear admiral is a naval commissioned officer rank above that of a commodore and captain, and below that of a vice admiral. It is generally regarded as the lowest of the "admiral" ranks, which are also sometimes referred to as "flag officers" or "flag ranks"...

in 1747 and replaced Admiral Peter Warren as the commander of the Western Squadron the same year. Hawke then put a great deal of effort into improving the performance of his crews and instilling in them a sense of pride and patriotism

Patriotism

Patriotism is a devotion to one's country, excluding differences caused by the dependencies of the term's meaning upon context, geography and philosophy...

. The Western Squadron had been established to keep a watch on the French Channel ports. Under a previous commander, Lord Anson, it had successfully contained the French coast and in May 1747 won the First Battle of Cape Finisterre when it attacked a large convoy leaving harbour.

The British had received word that there was now an incoming convoy arriving from the West Indies. Hawke took his fleet and lay in wait for the arrival of the French. In October 1747, Hawke captured six ships of a French squadron in the Bay of Biscay

Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Brest south to the Spanish border, and the northern coast of Spain west to Cape Ortegal, and is named in English after the province of Biscay, in the Spanish...

in the second Battle of Cape Finisterre

Second battle of Cape Finisterre (1747)

The Second Battle of Cape Finisterre was a naval battle which took place on 25 October 1747 during the War of the Austrian Succession...

. The consequence of this, along with Anson's earlier victory, was to give the British almost total control in the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

during the final months of the war. It proved ruinous to the French economy, helping the British to secure an acceptable peace at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748 ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled at the Imperial Free City of Aachen—Aix-la-Chapelle in French—in the west of the Holy Roman Empire, on 24 April 1748...

, despite the recent French conquest of the Austrian Netherlands. In recognition of his victory, Hawke was made a baronet

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

.

Peace

For Hawke, however, the arrival of peace brought a sudden end to his opportunities for active service. In 1747, he was elected as a Member of ParliamentMember of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

for the naval town of Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

, which he was to represent for the next thirty years. As one of the most celebrated Admirals of the recent war, Hawke was able to secure a command in the peace-time navy – and he was almost entirely at sea between 1748 and 1752.

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was considered by many merely to be an extended armistice and it was widely anticipated that a return to war was likely. Britain and France clashed over control of the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

and this colonial conflict escalated throughout 1754. Under Anson's direction, the British navy again began preparing for war.

Seven Years War

As it began to seem more likely that war would break out with France, Hawke was ordered to reactivate the Western Squadron – followed by a command to cruise of the coast of France intercepting ships bound for French harbours. He did this very successfully, and British ships captured more than 300 merchants ships during the period. This in turn further worsened relations between Britain and France, bringing them to the brink of declaring war. France would continue to demand the return of the captured merchant ships throughout the coming war.By early 1756, after repeated clashes in North America

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

, and deteriorating relations in Europe, the two sides were formally at war.

Fall of Minorca

Hawke was sent to replace Admiral John ByngJohn Byng

Admiral John Byng was a Royal Navy officer. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen he participated at the Battle of Cape Passaro in 1718. Over the next thirty years he built up a reputation as a solid naval officer and received promotion to Vice-Admiral in 1747...

as commander in the Mediterranean in 1756. Byng had been unable to relieve Minorca

Siege of Minorca

The Siege of Fort St Philip took place in 1756 during the Seven Years War.- Siege :...

following the Battle of Minorca

Battle of Minorca

The Battle of Minorca was a naval battle between French and British fleets. It was the opening sea battle of the Seven Years' War in the European theatre. Shortly after Great Britain declared war on the House of Bourbon, their squadrons met off the Mediterranean island of Minorca. The fight...

and he was sent back to Britain where he was tried and executed. Almost as soon as Minorca had fallen in June 1756, the French fleet had withdrawn to Toulon in case they were attacked by Hawke. Once he arrived off Minorca, Hawke found that the island had surrendered and there was little he could do to reverse this. He decided not to land the troops he had brought with him from Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

.

Hawke then spent three months cruising off Minorca

Minorca

Min Orca or Menorca is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. It takes its name from being smaller than the nearby island of Majorca....

and Marseille

Marseille

Marseille , known in antiquity as Massalia , is the second largest city in France, after Paris, with a population of 852,395 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Marseille extends beyond the city limits with a population of over 1,420,000 on an area of...

before returning home where he gave evidence against Byng. He was subsequently criticised by some supporters of Byng, for not having blockaded either Minorca or Toulon.

Descent on Rochefort

Hawke blockaded RochefortRochefort, Charente-Maritime

Rochefort is a commune in southwestern France, a port on the Charente estuary. It is a sub-prefecture of the Charente-Maritime department.-History:...

in 1757 and towards the end of the year he was selected to command a naval escort that would land a large force on the coast of France. The plan was to raid a town to hurt the French war effort, and force them to use troops to protect their own coastline, rather than sending them to Germany to attack Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

or Hanover

Hanover

Hanover or Hannover, on the river Leine, is the capital of the federal state of Lower Saxony , Germany and was once by personal union the family seat of the Hanoverian Kings of Great Britain, under their title as the dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg...

. Hawke, like many of the Generals, was extremely sceptical of the value of such a landing. The expedition was late setting off, further reducing its chances of success.

The expedition arrived off the coast of Rochefort in November. After storming the offshore island of Île-d'Aix

Île-d'Aix

Île-d'Aix is a commune in the Charente-Maritime department off the west coast of France. It occupies the territory of small island of Île d'Aix in the Atlantic. It is a popular place for tourist day-trips during the summer months.-Location:...

, the army commander Sir John Mordaunt

John Mordaunt (British Army officer)

General Sir John Mordaunt, KB was a British soldier and Whig politician, the son of Lieutenant-General Harry Mordaunt and Margaret Spencer...

hesitated before proceeding with the landing on the mainland. Despite a report by Colonel James Wolfe

James Wolfe

Major General James P. Wolfe was a British Army officer, known for his training reforms but remembered chiefly for his victory over the French in Canada...

that they would be able to capture Rochefort, Mordaunt was reluctant to attack.

Hawke then offered an ultimatum - either the Generals attacked immediately or he would sail for home. His fleet was needed to protect an inbound convoy from the West Indies, and could not afford to sit indefinitely off Rochefort. Mourdaunt hastily agreed, and the expedition returned to Britain without having made any serious attempt on the town. There was a later court of inquiry, but both Hawke and Mordaunt were cleared of any blame, and it was concluded that the conception of the attack of Rochefort had been an error. Despite this similar descents were launched the following year against Cherbourg and St Malo. For Hawke, the failure at Rochefort was a disappointment, and he remained sensitive about the issue for many years.

1758

For Britain, much of the war so far had been a disaster including the loss of Minorca and the failure at Rochefort. The rise of William PittWilliam Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham PC was a British Whig statesman who led Britain during the Seven Years' War...

to power, began to change things as he pushed a new strategy which involved expeditions against French colonies in Canada, Africa and the West Indies. Despite the failure of Rochefort, Pitt pushed for fresh landings on the French coast, believing they would be a useful distraction - preventing the French from sending troops to Germany or to the relief of their colonies around the globe.

In 1758 Hawke directed the blockade of Brest

Brest, France

Brest is a city in the Finistère department in Brittany in northwestern France. Located in a sheltered position not far from the western tip of the Breton peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French military port after Toulon...

for six months. In 1758 he was involved in a major altercation with his superiors at the Admiralty which saw him strike his flag and return to port over a misunderstanding at which he took offence. Although he later apologised, he was severely reprimanded. He was taken out of active service, but was later restored to command because the cabinet respected his talents of seamanship. In his absence a raid on St Malo had ended badly with the Battle of St Cast, which had seen a British force defeated and captured - bringing an end to the policy of descents, although it was now to be replaced with a far tighter blockade. In Hawke's absence the Channel Fleet had been under the command of Lord Anson.

Battle of Quiberon Bay

Planned French Invasion of Britain (1759)

A French invasion of Great Britain was planned to take place in 1759 during the Seven Years' War, but due to various factors including naval defeats at the Battle of Lagos and the Battle of Quiberon Bay was never launched. The French planned to land 100,000 French soldiers in Britain to end British...

from reaching Britain. A French army was assembled in Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

, with plans to combine the separate French fleets so they could seize control of the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

and allow the invasion force to cross and capture London. Hawke's orders were to prevent the large French fleets at Brest and Toulon from joining together. His ships continued their close blockade of Brest.

When Hawke's force was driven off station by a storm, the French fleet under Hubert de Brienne, Comte de Conflans

Hubert de Brienne, Comte de Conflans

Hubert de Brienne, Comte de Conflans was a French naval commander.-Early life:The son of Henri Jacob marquis de Conflans and Marie du Bouchet, at 15 he was made a knight of the Order of Saint Lazarus and the following year entered the Gardes de la Marine school at Brest...

, took advantage and left port. On 20 November 1759 he followed the French warships and during a gale he won a sufficient victory in the Battle of Quiberon Bay

Battle of Quiberon Bay

The naval Battle of Quiberon Bay took place on 20 November 1759 during the Seven Years' War in Quiberon Bay, off the coast of France near St. Nazaire...

, when combined with Edward Boscawen

Edward Boscawen

Admiral Edward Boscawen, PC was an Admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall. He is known principally for his various naval commands throughout the 18th Century and the engagements that he won, including the Siege of Louisburg in 1758 and Battle of Lagos...

's victory at Lagos, to remove the French invasion threat.

Although he had effectively put the French channel fleet out of action for the remainder of the war, Hawke was disappointed he had not secured a more comprehensive victory asserting that had he had two more hours of daylight the whole enemy fleet would have been taken. He occupied the île Dumet and returned home.

Blockade of France

Hawke's victory at Quiberon Bay ended any immediate hope of a major invasion of the British IslesBritish Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

. In spite of this the French continued to entertain hopes of a future invasion for the remainder of the war, which drove the British to keep a tight blockade on the French coast. This continued to starve French ports of commerce, further weakening France's economy. After a spell in England, Hawke returned to take command of the blockading fleet off Brest. The British were now effectively mounting a blockade of the French coast from Dunkirk to Marsielles. Hawke attempted to try and destroy some of the remaining French warships, which he had trapped in the Villaine Estuary. He sent in fireships but these failed to accomplish the task. Hawke developed a plan for landing on the coast, seizing a peninsular, and attacking the ships from land. However he was forced to abandon this when orders reached him from Pitt for a much larger expedition.

Capture of Belle Île

Belle Île

Belle-Île or Belle-Île-en-Mer is a French island off the coast of Brittany in the département of Morbihan, and the largest of Brittany's islands. It is 14 km from the Quiberon peninsula.Administratively, the island forms a canton: the canton of Belle-Île...

, off the coast of Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

and asked the navy to prepare for an expedition to take it. Hawke made his opposition clear in a letter to Anson, which was subsequently widely circulated. Pitt was extremely annoyed by this, considering that Hawke had overstepped his authority. Nonetheless Pitt pressed ahead with the expedition against Belle Île. An initial assault in April 1761 was repulsed with heavy loss but, reinforced, the British successfully captured the island in June.

Although the capture of the island provided another victory for Pitt, and lowered the morale of the French public by showing that the British could now occupy parts of Metropolitan France

Metropolitan France

Metropolitan France is the part of France located in Europe. It can also be described as mainland France or as the French mainland and the island of Corsica...

– Hawke’s criticisms of its strategic usefulness were borne out. It was not a useful staging point for further raids on the coast and the French were not especially concerned about its loss, telling Britain during subsequent peace negotiations that they would offer nothing to exchange for it and Britain could keep it if they wished. Britain soon sent much of the garrison of the island to Martinique

Martinique

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, with a land area of . Like Guadeloupe, it is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. To the northwest lies Dominica, to the south St Lucia, and to the southeast Barbados...

and Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

to take part in other operations.

First Lord of the Admiralty

Falklands Crisis (1770)

The Falklands Crisis of 1770 was a diplomatic standoff between Britain and Spain over possession of the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. These events were nearly the cause of a war between France, Spain and Britain — the countries poised to dispatch armed fleets to contest the barren...

. He was succeeded by Lord Sandwich

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, PC, FRS was a British statesman who succeeded his grandfather, Edward Montagu, 3rd Earl of Sandwich, as the Earl of Sandwich in 1729, at the age of ten...

. He was appointed to the Privy Council in 1766.

Naval reforms

During his time as First Lord, Hawke was successful in bringing the navy's spending under control. Hawke oversaw Britain's naval mobilisation during the Falkland's Crisis. Britain faced a resurgent France trying to rebuild its power by enlarging its navy and gaining new colonies while Hawke was forced to reduce the costs of the Royal Navy which had peaked during the Seven Years' War when over a hundred Ships-of-the-line were in service.Retirement

He was made a baron in 1776. Towards the end of his life he lived at SwaythlingSwaythling

Swaythling was once a village but over the years it has gradually become a suburb and electoral ward of Southampton in Hampshire, England. The ward has a population of 13,394....

House, near Southampton, although he died in Sunbury-on-Thames

Sunbury-on-Thames

Sunbury-on-Thames, also known as Sunbury, is a town in the Surrey borough of Spelthorne, England, and part of the London commuter belt. It is located 16 miles southwest of central London and bordered by Feltham and Hampton, flanked on the south by the River Thames.-History:The earliest evidence of...

. His memorial, depicting the Battle of Quiberon Bay, is in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

St. Nicolas' Church is an Anglican parish church at North Stoneham, Hampshire which originated before the 15th century and is known for its "One Hand Clock" which dates from the early 17th century, and also for various memorials to the famous.-Location:...

near Swaythling. He was succeeded in his title by his son Martin Hawke, 2nd Baron Hawke

Martin Hawke, 2nd Baron Hawke

Martin Bladen Hawke, 2nd Baron Hawke was a British peer and politician.-Background:Hawke was the son of Admiral Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, and Catherine, daughter of Walter Brooke. He was educated at the University of Oxford.-Political career:Hawke sat as Member of Parliament for Saltash from...

.

Legacy

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. His best-known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde....

story of Long John Silver

Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a fictional character and the primary antagonist of the novel Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson. Silver is also known by the nicknames "Barbecue" and the "Sea-Cook".- Profile :...

, who claims to have served under Hawke. Another character calls the admiral "the immortal Hawke".

Places named after Hawke

- Cape HawkeCape HawkeCape Hawke is a coastal headland in Australia on the New South Wales coast, just south of Forster/Tuncurry and within the Booti Booti National Park....

, New South Wales - Hawke BayHawke BayHawke Bay is a large bay on the eastern coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It stretches from the Mahia Peninsula in the northeast to Cape Kidnappers in the southwest, a distance of some 100 kilometres....

, New Zealand - Hawke's BayHawke's BayHawke's Bay is a region of New Zealand. Hawke's Bay is recognised on the world stage for its award-winning wines. The regional council sits in both the cities of Napier and Hastings.-Geography:...

, New Zealand region adjacent to Hawke Bay - Hawke's Bay, Newfoundland and LabradorHawke's Bay, Newfoundland and LabradorHawke's Bay is a town at the mouth of Torrent River southeast of Point Riche in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The town was named after Edward Hawke by James Cook in 1766. This was to commemorate Hawke's victory in the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759...

Organisations adopting the Hawke title:

- Hawke Sea Scouts, New Zealand - Martin Hawke, 7th Baron HawkeMartin Hawke, 7th Baron HawkeMartin Bladen Hawke, 7th Baron Hawke of Towton , generally known as Lord Hawke, was an English amateur cricketer who played major roles in the sport's administration....

consented to use of family name, crest and became patron

He lends his name to a boarding house at The Royal Hospital School

Many English public houses bear the name 'Admiral Hawke' in his honour.

External links

- Chap. II, Hawke: The Spirit, in

|-

|-

|-

|-