Economic history of the United Kingdom

Encyclopedia

The economic history of the United Kingdom deals with the history of the economy

of the United Kingdom

from the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain

on May 1st, 1707, with the political union

of the Kingdom of England

and the Kingdom of Scotland

. This Union, as well as being political, was designed to be a full economic union, with most of the twenty-five Articles of the Treaty of Union

dealing with economic arrangements for the new state. In 1801, Great Britain united with Ireland

to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

.

The United Kingdom developed as one of the world's leading economies. Between 1870 and the end of the 20th century, economic output per head of population in Britain rose by 500 per cent, generating a significant rise in living standards. However, from the late 19th century onwards Britain experienced a relative economic decline when compared to the world's other leading economies. In 1870, Britain's output per head was the second highest in the world after Australia. By 1914, it was fourth highest, having been overtaken. In 1950, British output per head was still 30 per cent ahead of the six founder members of the EEC

, but within 50 years it had been overtaken by many European and several Asian countries.

, an economic theory that stressed maximizing the trade inside the empire, and trying to weaken rival empires. The modern British Empire was based upon the preceding English Empire which first took shape in the early 17th century, with the English settlement of the eastern colonies of North America

, which later became the United States

, as well as Canada

's Maritime provinces, and the colonizations of the smaller islands of the Caribbean

such as Trinidad and Tobago

, the Bahamas, the Leeward Islands

, Barbados

, Jamaica

and Bermuda

. These sugar

plantation islands, where slavery

became the basis of the economy, were part of Britain's most important and successful colonies. The American colonies also utilized slave labor in the farming of tobacco

, cotton

, and rice

in the south. Britain's American empire was slowly expanded by war and colonization. Victory over the French during the Seven Years' War

gave Britain control over almost all of North America

but had only a small economic role.

Mercantilism was the basic policy imposed by Britain on its colonies. Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants--and kept others out--by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximize exports from and minimize imports to the realm. The government had to fight smuggling--which became a favorite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch. The goal of mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a superb Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. Thus the British Navy captured New Amsterdam

(New York) in 1664. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.

.

It has been argued by historians such as Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, and E.P. Thompson that the foundations of this process of change can be traced back to the Puritan Revolution in the Seventeenth Century. This produced landed and merchant elites alive to the benefits of economic change, and a system of agriculture able to produce increasingly cheap food supplies. To this must be added the influence of religious nonconformity, which increased literacy and inculcated a 'Protestant work ethic

' amongst skilled artisans.

A long run of good harvests, starting in the first half of the 18th century, resulted in an increase in disposable income and a consequent rising demand for manufactured goods, particularly textiles. The invention of the flying shuttle

by John Kay

enabled wider cloth to be woven faster, but also created a demand for yarn that could not be fulfilled. Thus, the major technological advances associated with the industrial revolution were concerned with spinning. James Hargreaves

created the Spinning Jenny

, a device that could perform the work of a number of spinning wheels. However while this invention could be operated by hand, the water frame

, invented by Richard Arkwright

, could be powered by a water wheel

. Indeed, Arkwright is credited with the widespread introduction of the factory system

in Britain, and is the first example of the successful mill owner and industrialist in British history. The water frame was, however, soon supplanted by the spinning mule

(a cross between a water frame and a jenny) invented by Samuel Crompton

. Mules were later constructed in iron by Messrs. Horrocks of Stockport.

As they were water powered, the first mills were constructed in rural locations by streams or rivers. Workers villages were created around them. Styal Mill (owned by the National Trust

) is a surviving example of this kind of enterprise, as are New Lanark

Mills in Scotland. These spinning mills resulted in the decline of the domestic system, in which spinning was undertaken in rural cottages.

However, the textile trade was transformed, as was much else, by the development of the steam engine

. The first practicable steam engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen

, and was used for pumping water out of mines. It was perfected by James Watt

, being transformed into a reciprocating engine

capable of powering machinery. The first steam-driven textile mills began to appear in the last quarter of the 18th century, and this transformed the industrial revolution into an urban phenomenon, greatly contributing to the appearance and rapid growth of industrial towns.

The progress of the textile trade soon outstripped the original supplies of raw materials. By the turn of the 19th century, imported American cotton

had replaced wool

in the North West of England, though the latter remained the chief textile in Yorkshire

. Textiles have been identified as the catalyst in technological change in this period. The application of steam power stimulated the growth of the coal

industry, the construction of mills and the demand for machinery and engines impacted upon the iron industry, and the demand for imported raw materials (and later improved means of export and distribution) led to the growth of the canal

system, and later the invention and spread of the railway.

Such an unprecedented degree of economic growth could not be sustained by domestic demand. The application of technology and the factory system created such levels of mass production

and cost efficiency that enabled Britain to undercut foreign competitors. The political dominance created by the growth of an overseas empire and the strategic control of the world's seas by the Royal Navy

, enabled British manufacturers to export their goods to Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Indeed, the demands of the war economy created by the French and Napoleonic Wars

added to these opportunities.

Walt Rostow

has posited the 1790s as the take-off period for the industrial revolution. This means that a process previously responding to domestic and other external stimuli began to feed upon itself, and became an unstoppable and irreversible process of sustained industrial and technological expansion.

In the late 18th century and early 19th century a series of technological advances led to the Industrial Revolution

. Britain's position as the world's pre-eminent trader helped fund research and experimentation. The nation was also gifted by some of the world's greatest reserves of coal

, the main fuel of the new revolution.

It was also fuelled by a rejection of mercantilism in favour of the predominance of Adam Smith

's capitalism

. The fight against Mercantilism was led by a number of liberal

thinkers, such as Richard Cobden

, Joseph Hume

, Francis Place

and John Roebuck

.

Some have stressed the importance of natural or financial resources that Britain received from its many overseas colonies or that profits from the British slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean helped fuel industrial investment. It has been pointed out, however, that slave trade and the West Indian plantations provided less than 5% of the British national income during the years of the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution saw a rapid transformation in the British economy and society. Previously large industries had to be near forests or rivers for power. The use of coal-fuelled engines allowed them to be placed in large urban centres. These new factories proved far more efficient at producing goods than the cottage industry of a previous era. These manufactured goods were sold around the world, and raw materials and luxury goods were imported to Britain.

During the Industrial Revolution the empire became less important and less well-regarded. The British defeat in the American War of Independence (1775–1783) deprived it of one of its most populous colonies. This loss of the southern American colonies was coupled with a realisation that colonies were not particularly economically beneficial. It was realised that the costs of occupation of colonies often exceeded the financial return to the taxpayer. In other words, formal empire afforded no great economic benefit when trade would continue whether the overseas political entities were nominally sovereign or not. The American Revolution helped demonstrate this by showing that Britain could still control trade with the colonies without having to pay for their defence and governance. Capitalism encouraged the British to grant their colonies self-government. The end of the old colonial system was most evident in the repeal of the Corn Laws

, the agricultural subsidies on colonial grain. The end of these laws opened the British market to unfettered competition, grain prices fell, and food became more plentiful. The repeal greatly injured Canada

, however, whose grain exports lost a great deal of their profitability.

Some argue that this push for free trade was merely because of Britain economic position and was unconnected with any true philosophic dedication to free trade. Roughly between the Congress of Vienna

and the Franco-Prussian War

, Britain reaped the benefits of being the world's sole modern, industrialised nation. Following the defeat of Napoleon, Britain was the 'workshop of the world', meaning that its finished goods were produced so efficiently and cheaply that they could often undersell comparable, locally manufactured goods in almost any other market. If political conditions in particular overseas markets were stable enough, Britain could dominate its economy through free trade alone without having to resort to formal rule or mercantilism. Britain was even supplying half the needs in manufactured goods of such nations as Germany

, France

, Belgium

, and the United States

.

Britain, in this sense, continued to adhere to the Cobdenite notion that informal colonialism was preferable — the established consensus among industrial capitalists during the age of Pax Britannica

between the downfall of Napoleon and the Franco-Prussian War.

Sovereign areas already hospitable to informal empire largely avoided formal rule, even often during the shift to New Imperialism. China

, for instance, was not a backward country unable to secure the prerequisite stability and security for western-style commerce, but an empire unwilling to admit western commerce, which may explain the West's contentment with informal 'Spheres of Influence'. China, unlike tropical Africa

, was a securable market without formal control.

The victory of the forces of the East India Company

at the Battle of Plassey

(1757) opened the great Indian province of Bengal

to British rule, although the famine of 1770

, exacerbated by massive expropriation of provincial government revenues, aroused controversy at home. The 19th century saw Company rule extended across India after expelling the Dutch, French and Portuguese. Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857

British India came under the direct rule of the British government. The territory continued to expand as Ceylon (now Sri Lanka

) and Burma (now Myanmar

) were added to Britain's Asian territories, which extended further east to Malaya

and (1841) to Hong Kong

following a successful war in defence of the Company's opium

exports to China

.

During the First Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant

During the First Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant

as the dominant figure in the capitalist

system. In the latter decades of the 19th century, when the ultimate control and direction of large industry came into the hands of financier

s, industrial capitalism gave way to financial capitalism and the corporation

. The establishment of behemoth industrial empires, whose assets were controlled and managed by men divorced from production, was a dominant feature of this third phase.

New products and services were also introduced which greatly increased international trade. Improvements in steam engine

design and the wide availability of cheap steel

meant that slow, sailing ships could be replaced with steamships, such as Brunel's

SS Great Western

. Electricity

and chemical

industries also moved to the forefront. In many of these sectors Britain had far less of an edge than other powers such as Germany

and the United States

, who both rose to equal and even surpass Britain in economic heft.

Amalgamation of industrial cartel

s into larger corporations, mergers and alliances of separate firms, and technological advancement (particularly the increased use of electric power and internal combustion engine

s fuelled by coal

and petroleum

) were mixed blessings for British business during the late Victorian era

. The ensuing development of more intricate and efficient machines along with monopolistic

mass production

techniques greatly expanded output and lowered production costs. As a result, production often exceeded domestic demand. Among the new conditions, more markedly evident in Britain, the forerunner of Europe's industrial states, were the long-term effects of the severe Long Depression

of 1873-1896, which had followed fifteen years of great economic instability. Businesses in practically every industry suffered from lengthy periods of low — and falling — profit rates and price deflation after 1873.

Long-term economic trends led Britain, and to a lesser extent, other industrialising nations such as the United States

and Germany

, to be more receptive to the desires of prospective overseas investment. Through their investments in industry, bank

s were able to exert a great deal of control over the British economy

and politics

. Cut-throat competition in the mid-19th century caused the creation of super corporations and conglomerates

. Many companies borrowed

heavily to achieve the vast sums of money required to take over

their rivals, resulting in a new capitalist

stage of development.

By the 1870s, financial houses in London

had achieved an unprecedented level of control over industry. This contributed to increasing concerns among policymakers over the protection of British investments overseas — particularly those in the securities of foreign governments and in foreign-government-backed development activities, such as railways. Although it had been official British policy to support such investments, with the large expansion of these investments in the 1860s, and the economic and political instability of many areas of investment (such as Egypt

), calls upon the government for methodical protection became increasingly pronounced in the years leading up to the Crystal Palace Speech. At the end of the Victorian era, the service sector (banking, insurance and shipping, for example) began to gain prominence at the expense of manufacturing.

As foreign trade increased, so in proportion did the amount of it going outside the Continent. In 1840, £7.7 million of its export and £9.2 million of its import trade was done outside Europe; in 1880 the figures were £38.4 million and £73 million. Europe's economic contacts with the wider world were multiplying, much as Britain's had been doing for years. In many cases, colonial control followed private investment, particularly in raw materials and agriculture. Intercontinental trade between North and South constituted a higher proportion of global trade in this era than in the late 20th century period of globalisation.

and World War, Europe added almost 9 million square miles (23,000,000 km²) — one-fifth of the land area of the globe — to its overseas colonial possessions. Ushering out the cavalier colonialism of the mid-Victorian era, the age of Pax Britannica, the late 19th century Romantic Age was an era of "empire for empire's sake". But scholars debate the causes and ramifications of this period of colonialism, dubbed "The New Imperialism" to distinguish it from earlier eras of overseas expansion, such as the mercantilism of the 16th to 18th centuries or the liberal age of 'free trade' colonialism of the mid-19th century.

Continental political developments in the late 19th century, relating to the overall breakdown of the Concert of Europe

, also rendered this imperial competition feasible, in spite of Britain

's centuries of long-established naval and maritime superiority. As unification of Germany

by the Prussia

n 'Garrison State' went forward, contending capitalist powers were thus ready to compete with Britain over stakes in overseas markets. The aggressive nationalism of Napoleon III

and the relative political stability of France

under the liberal Third Republic also rendered France more capable of challenging Britain's global preeminence. Germany, Italy

, and France were simply no longer as embroiled in continental concerns and domestic disputes as they were before the Franco-Prussian War

.

Contemporary world-systems theorist Immanuel Wallerstein

perhaps better addresses the counter-arguments to Hobson without degrading his underlying inferences. Wallerstein's conception of imperialism as a part of a general, gradual extension of capital investment from the "center" of the industrial countries to an overseas "periphery" thus coincides with Hobson's. According to Wallerstein, "Mercantilism... became the major tool of [newly industrialising, increasingly competitive] semi-peripheral countries [Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, etc.] seeking to become core countries." Wallerstein hence perceives formal empire as performing a function "analogous to that of the mercantilist drives of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England and France."

The expansion of the Industrial Revolution hence contributed to the emergence of an era of aggressive national rivalry, leading to the late 19th century 'scramble for Africa' and formal empire. Hobson's theory is thus useful in explaining the role of over-accumulation in overseas economic and colonial expansionism while Wallerstein perhaps better explains the dynamic of inter-capitalist geopolitical competition.

Recent developments made it easier and more appealing for "semi-peripheral" newly industrialised states to challenge Pax Britannica overseas. With the expansion of the Industrial Revolution, Britain could no longer reap the benefits of being the sole modern, industrial nation. Britain by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War was no longer the 'workshop of the world', meaning that its finished goods were no longer produced so efficiently and cheaply that they could often undersell comparable, locally manufactured goods in almost any other market.

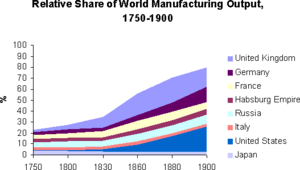

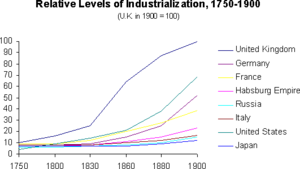

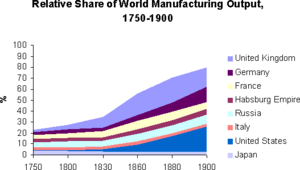

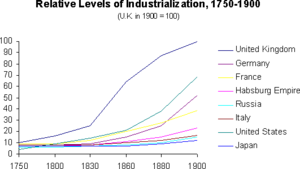

As these other newly industrial powers, the United States, and Japan

after the Meiji Restoration

began industrialising at a rapid rate, Britain's comparative advantage in trade of any finished good began diminishing. Just as the power of German and North American capitalisms increased, the relative decline of the British capitalist economy began in the last third of the 19th century, contributing to a breakdown of Britain's natural superiority in industry and commerce. Britain's share of world trade fell from one-fourth in 1880, one-sixth in 1913, and one-eighth in 1948. Britain was no longer supplying half the needs in manufactured goods of such nations as Germany, France, Belgium

, and the United States. Britain was even growing incapable of dominating the markets of India — a crown colony by 1858 that Disraeli

would later deem "the brightest jewel of the crown" —, Manchu China

, the coasts of Africa, and Latin America.

To make matters worse, British manufactures in the staple industries of the Industrial Revolution

were beginning to experience real competition abroad. The German textiles and metal industries, for example, had by the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War surpassed those of Britain in organisation and technical efficiency and usurped British manufacturers in the domestic market. By the turn of the 20th century, the German metals and engineering industries would be producing heavily for the free trade market of what was once "workshop of the world" as well. In midst of Britain's relative industrial decline, the fact that invisible financial exports actually kept Britain "out of the red" is somewhat indicative of both Britain's pressure to secure overseas markets in both nominally independent states and colonies and its newly precarious hegemony over overseas markets.

For the most part, formal empire has its roots in the breakdown of Pax Britannica. With the rise of industrial capitalism in Germany, North America, and Japan, its finished goods no longer had a comparative or absolute advantage in any other market. Industrialisation progressed dynamically in Germany and the United States especially, allowing them to clearly prevail over the "old" French and English capitalisms. The "neo-mercantilist" practices of newly industrialising states such as Germany, the United States, and Japan cut Britain off from outlets and even created competition for Britain in sales to these 'peripheral' areas.

With contending, emerging 'semi-peripheral' capitalist powers once dependent on British industry ready to vie for competing stakes in overseas markets, inter-capitalist competition also took form of protectionism through higher tariffs, further aggravating the push toward overseas markets: in Germany in 1879, and again following 1902: in the United States in 1890; in France in 1892, 1907, and 1910. The only country to escape this trend was Britain, whose essential strength lay precisely in its preeminence on the world market. German, American, and French imperialists, as mentioned, argued that Britain's world power position gave the British unfair advantages on international markets, thus limiting their economic growth.

This affected Britain in two ways. First, of course, new interest of the emergent industrial powers in colonial expansion brought them into direct competition with Britain. The expansion of the Second Industrial Revolution and the rise of similar economic practices (such as amalgamation of industry) in Germany and the United States intensified the competition for overseas markets and hence formal colonialism.

New Imperialism, as one means of facilitating the inexorable movement of capital from domestic markets to overseas areas, was thus enabled by recent changes in the North Atlantic balance of power, such as the unification of Germany under Prussia and relative political stability under France's Third Republic, but driven by changing economic realities and the spread of industrial capitalism beyond Britain.

By the time Benjamin Disraeli

ushered in the age of New Imperialism with his watershed Crystal Palace Speech, which was delivered by no mere coincidence after the Franco-Prussian War and during the Long Depression, Britain was no longer the world's sole modern, industrial nation. Pessimists thus inferred that unless Britain acquired secure colonial markets for its industrial products and secure sources of raw materials, the other industrial states would seize them themselves and would precipitate a more rapid decline of British business, power, and standards of living. The prospect of having to compete to remain the forerunner of the world's economies and empires due to recent changes in the global economy and continental balance of power thus left it ripe for Disraeli's Conservative rule in the 1870s, which would usher in an era of extreme national rivalry that would one day culminate in the Great War.

In this sense, historian Bernard Porter argues that formal imperialism for Britain was a symptom and an effect of its relative decline in the world, and not of strength. Symbolic overtures, in fact, such as Queen Victoria

's grandiose title of "Empress of India", celebrated during Disraeli's second premiership in the 1870s, helped to obscure this fact. Joseph Chamberlain thus argued that formal imperialism was necessary for Britain because of the relative decline of the British share of the world's export trade and the rise of German, American, and French economic competition.

As mentioned, the 'Scramble for Africa', rationalised by Rudyard Kipling

-style racism and Social Darwinism

in predominantly Protestant

empires and the paternalistic ,but republican, French-style "mission of civilisation", was attractive to many European statesmen and industrialists who wanted to accelerate the process of securing colonies upon anticipating the prospective need to do so. Their reasoning was that markets might soon become glutted, and that a nation's economic survival depends on its being able to offload its surplus products elsewhere.

At a time when the abandonment of free trade limited the European market, some business and government leaders, such as Leopold II and Jules Ferry, concluded that sheltered overseas markets would solve the problems of low prices and over-accumulation of surplus capital caused by shrinking continental markets. Among the new conditions were the short-term effects of the severe economic depression of 1873, which had followed fifteen years of great economic instability. Business after 1873 in practically every industry suffered from lengthy periods of low profit rates and deflation; profits were falling because too much capital were chasing too few markets, especially after the rise of newly industrialising states in export trade with its traditional markets in continental Europe, China, and Latin America.

In addition, such surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap labour, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement to imperialism, of course, arose from the demand for raw materials unavailable in Europe, especially copper, cotton, rubber, tea, and tin, to which European consumers had grown accustomed and European industry had grown dependent.

Following the lead of Britain under Disraeli, even the once hesitantly imperialistic Bismarck was eventually brought to realise the value of colonies for securing (in his words) "new markets for German industry, the expansion of trade, and a new field for German, activity, civilisation, and capital". Examples of strategic competition following the passing of the scene of Bismarck, the era's premier diplomat, that would intensify the drive to consolidate existing spheres of influence and grab new colonies, include the Moroccan Crisis of 1905, the Tangier Crisis resulting from Kaiser Wilhelm's recognition of Moroccan

independence, and the second Moroccan Crisis, in which Germany sent its navy to Morocco, thereby testing the precarious Anglo-French Entente. The Entente Cordiale

, in fact, was a gentlemen's agreement

between Britain and France to curtail further German expansion. The Entente Cordiale and the Franco-Russian alliances were also made because of a common interest.

The absolutist Central Powers, led by a newly unified, dynamically industrialising Germany, with its expanding navy — doubling in size between the Franco-Prussian War and the Great War — were a strategic threat to the markets of these relatively declining empires that would one day consist of the Great War Allies. British policymakers feared the prospect of another German military victory over France, which could have reasonably resulted in a German take-over of France's formal colonies, a sort of reversal of the actual outcome of the Great War, after which Britain occupied the vast majority of German and Ottoman colonies as "protectorates". This prospect was especially frightening considering that French colonies tended to be closely situated to Britain's; Nigeria, for instance, was surrounded by French territory, India was near French Indochina, and so forth.

by the belligerent Kaiser Wilhelm II, the expropriation of vast, unexplored areas of Asia and Africa by emerging imperial powers such as Italy and Germany and more-established empires such as Britain and France was relatively orderly. The 1885 Congress of Berlin

, initiated by Bismarck to establish international guidelines for the acquisition of African territory, formalised this new phase in the history of Western imperialism

. Between the 1870 Franco-Prussian War

and World War I

(the age of New Imperialism

), Europe added almost 9 million square miles (23,000,000 km²) — one-fifth of the land area of the globe — to its overseas colonial possessions.

Since the "Scramble for Africa

" was the predominant feature of New Imperialism and formal empire, opponents of Hobson

's accumulation theory often point to frequent cases when military and bureaucratic costs of occupation exceeded financial returns. In Africa (exclusive of South Africa

) the amount of capital investment by Europeans was relatively small before and after the 1885 Congress of Berlin, and the companies involved in tropical African commerce were small and politically insignificant, exerting only a tiny influence on domestic politics. First, this observation might detract from the pro-imperialist arguments of Leopold II of Belgium

, Italian premier Francesco Crispi

, and French Republican Jules Ferry

, but Hobson argued against imperialism from a slightly different standpoint. He concluded that finance was manipulating events to its own profit, but often against broader national interests.

Second, any such statistics only obscure the fact that African formal control of tropical Africa had strategic implications in an era of feasible inter-capitalist competition, particularly for Britain, which was under intense economic and thus political pressure to secure lucrative markets such as India, China, and Latin America. In Britain's case this process of capitalist diffusion had in many regions led it to acquire colonies in the interests of commercial security; France and Germany would later follow suit. For example, although the then inconspicuously moribund Czarist Empire proved to be little threat to Great Britain following its stunning defeat in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War

, British Conservatives in particular feared that Russia would continue to usurp Ottoman territory and acquire a port on the Mediterranean or even Constantinople

— a long touted goal of orthodox Russia.

These fears became especially pronounced following the 1869 completion of the near-by Suez Canal

, prompting the official rationale behind British premier Disraeli's purchase of the waterway. The close proximity of the Czar's (territorially) expanding empire in Central Asia to India also terrified Lord Curzon, thus triggering the Afghan Wars

. Cecil John Rhodes

and Milner

also advocated the prospect of a "Cape to Cairo" empire

, which would link by rail the extrinsically important canal to the intrinsically mineral and diamond

rich South, from a strategic standpoint. Though hampered by German conquest of Tanganyika

until the end of the Great War, Rhodes successfully lobbied on behalf of such a sprawling East African empire.

Formal colonies were often, in hindsight, strategic outposts to protect large zones of 'investment', such as India, Latin America, and China. Britain, in as sense, continued to adhere to the Cobdenite

notion that informal colonialism was preferable — the established consensus among industrial capitalists during the age of Pax Britannica between the downfall of Napoleon and the Franco-Prussian War. What changed since the Disraeli's Crystal Palace Speech was not necessarily a preference for colonialism

over informal empire, but the attitude toward formal rule in largely tropical areas once considered too 'backward' for trade. Sovereign areas already hospitable to informal empire largely avoided formal rule during the shift to New Imperialism. China, for instance, was not a backward country unable to secure the prerequisite stability and security for western-style commerce, but a highly advanced empire unwilling to admit western (often drug-pushing

) commerce, which may explain the West's contentment with informal 'Spheres of Influences'. China, unlike tropical Africa, was a securable market without formal control.

Following the First Opium War

(1839–1842), British commerce, and later capital invested by other newly industrialising powers, was securable with a smaller degree of formal control than in Southeast Asia, West Africa, and the Pacific. But in many respects, China was a colony and a large-scale receptacle of Western capital investments. Western powers did intervene military there to quell domestic chaos, such as the horrific Taiping Rebellion

(1851–1864) and the anti-imperialist Boxer Rebellion

(1901). For example, General Gordon, later the imperialist 'martyr' in the Sudan

, is often accredited as having saved the Manchu Dynasty from the Taiping insurrection, after having defeated the Manchu in the Second Opium War

(1856–60).

Colonialism in India, however, should dissuade sweeping generalisations and over-simplifications regarding the roles of inter-capitalist competition and accumulated surplus in precipitating the era of New Imperialism. Formal empire in India

, beginning with the Government of India Act of 1858, was a means of consolidation, reacting to the abortive Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, which was in itself a conservative reaction among Indian traditionalists to the Dalhousie era of liberalisation and consolidation of the subcontinent. Local concerns in particular zones of investment, hence, should be of concern as well.

Formal empire in Sub-Saharan Africa, the last vast region of the world largely untouched by "informal imperialism" and "civilisation", was also attractive to Europe's ruling elites for other potential reasons. First, insofar as the "Dark Continent" was agricultural or extractive, and no longer "stagnant" since its integration with the world's interdependent capitalist economy, it required more capital for development that it could provide itself. Second, during a time when in nearly every year since the 1813 liberalisation of trade onward Britain's balance of trade

showed a deficit, and a time of shrinking and increasingly protectionist continental markets, Africa offered Britain an open market that would garner it a trade surplus — a market that bought more from the metropole than it sold overall. Britain, like most other industrial countries, had long since begun to run an unfavourable balance of trade (which was increasingly offset, however, by the income from overseas investments). As perhaps the world's first post-industrial nation, financial services became an increasingly more important sector of its economy. Invisible financial exports, as mentioned, kept Britain out of the red, especially capital investments outside Europe, particularly to the developing and open markets in Africa, predominantly white 'settler

colonies', the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific.

Each of Britain's major elites also found some advantages in formal, overseas expansion: mammoth monopolies wanted imperial support to secure overseas investments against competition and domestic political tensions abroad; bureaucrats wanted more occupations, military officers desired promotion, and the traditional but waning landed gentry wanted formal titles. Observing the rise of trade unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during an era of mass society in both Europe and later North America, the elite in particular was able to utilise imperial "jingoism

" to co-opt the support of the impoverished industrial working class. Riding the sentiments of the late 19th century Romantic Age, imperialism inculcated the masses with 'glorious' neo-aristocratic virtues and helped instil broad, nationalist

sentiments.

and Germany

, had developed their own industries; the United Kingdom

's comparative economic advantage had lessened, and the ambitions of its rivals had grown. The losses and destruction of World War I

, the depression in its aftermath

during the 1930s, and decades of relatively slow growth eroded the United Kingdom's pre-eminent international position of the previous century.

By 1921, more than 2,000,000 Britons were unemployed as a result of the postwar economic downturn. By 1926, the economy was still struggling, the general strike

of that year doing it no favours. Industrial relations briefly improved, but then came the Wall Street stock market crash

in the USA, which sparked a Great Depression

. See also the Great Depression in the United Kingdom

.Unemployment had stood at less than 1,800,000 at the end of 1930, but by the end of 1931 it had risen sharply to more than 2,600,000.By January 1933, however, more than 3,000,000 Britons were unemployed, accounting for more than 20% of the workforce. Although this record for unemployment would be exceeded numbers-wise 50 years later, it has still yet to be exceeded as a percentage almost 80 years on.

The rest of the 1930s saw a decent economic recovery and fall in unemployment, and by 1938 the unemployment rate had fallen to around 10%.

In World War II

, which started in September 1939, there was again a great deal of destruction to British infrastructure, and the years after the war also saw Britain lose almost all of its remaining colonies as the empire dissolved. In the 1945 general election

, just after the war's end, the Labour Party

was elected, introducing sweeping reforms of the British economy. Taxes increased, industries were nationalised, and a welfare state

with national health, pensions, and social security was created.

The next years saw some of the most rapid growth Britain had ever experienced, recovering from the devastation of the Second World War and then expanding rapidly past the previous size of the economy. By 1959, tax cuts had helped boost living standards and allow for a strong economyand low unemployment.

By the end of the 1960s, this growth began to slow and unemployment was rising again.

During the 1970s Britain suffered a long running period of relative economic malaise, dogged by severe inflation, strikes and union power as well as inflation, with neither the Conservative

government of 1970

-1974

(led by Edward Heath

) nor the Labour

government which succeeded it (led by Harold Wilson

and from 1976 James Callaghan

) being able to halt the country's economic decline.

Unemployment exceeded 1,000,000 by 1972 and had risen even higher by the time the end of the decade was in sight.

This led to the election of Margaret Thatcher

, who cut back on the government's role in the economy and weakened the power of the trade union

s. The latter decades of the 20th century have seen an increase in service-providers and a drop in industry, combined with privatisation of some sections of the economy. This change has led some to describe this as a 'Third Industrial Revolution', though this term is not widely used.

and the United States were becoming the biggest threats in terms of domestic economic production, having vastly superior natural resources compared to Britain. Furthermore, Germany had developed its own policy of imperialism

which led to friction with other imperial powers in Europe up to the First World War

.

Even with the decline, in 1914 London was still the center of international payments, and a large creditor nation, owed money by others. The First World War

(1914–1918) saw absolute losses for Britain’s economy. It is estimated that she lost a quarter of her total wealth in fighting the war. Failure to appreciate the damage done to the British economy led to the pursuit of traditional liberal economic policies which plunged the country further into economic dislocation with high unemployment (reaching 2,000,000 in 1921)and sluggish growth.

By 1926, a General Strike

was called by trade unions but it failed, and many of those who had gone on strike were blacklisted, and thus were prevented from working for many years later.

affected Britain resulting in leaving the Gold Standard

. Whereas Britain had championed the concept of the free market when it was ascendant in the world economy, it gradually withdrew to adopting Tariff Reform as a measure of protectionism. By the early 1930s, the depression again signaled the economic problems the British economy faced. Unemployment soared during this period; from just over 10% in 1929 to more than 20% by early 1933. However, it had fallen to 13.9% by the start of 1936.

When the Labour Government collapsed in 1931, it was replaced by a National Government representing all the troubles that had beset the country. Britain was not alone, with equal economic troubles affecting most European countries, most powerfully Germany.

In political terms, the economic problems found expression in the rise of radical movements who promised solutions which conventional political parties were no longer able to provide. In Britain this was seen with the rise of the Communist Party of Great Britain

(CPGB) and the Fascists under Oswald Mosley

. However, their political strength was limited and they never posed any real threat to the conventional political parties in the UK.

Britain’s economic problems are cited as a reason for appeasement

. Delaying a commitment to war was a means of buying time to divert scarce economic resources into the production of military hardware and armaments.

reserves to pay for munitions, raw materials and industrial equipment from American factories. By the third quarter of 1940 the volume of British exports was down 37% compared to 1935. Although the British Government had committed itself to nearly $10,000 million of orders from America, Britain's gold and dollar reserves were near exhaustion. The American Government decided to prop up Britain as it neared bankruptcy, so on 10 January 1941 they produced a Bill entitled an "Act to promote the defence of the United States" (its number, H.R. 1776, was the year of American independence) which was put before the United States Congress

and which was enacted on 11 March 1941. This Act became known as Lend-Lease

, whereby America would give Britain cash totaling $31.4 billion which never had to be repaid. One month later British gold and dollar reserves had dwindled to their lowest ever point, $12 million. Under this new agreement with the American Government, Britain agreed not to export any articles which contained Lend-Lease material or to export any goods—even if British-made—which were similar to Lend-Lease goods. The American Government sent officials to Britain to police these requirements. By 1944 British exports had gone down to 31% from 1938. Lend-Lease created problems in reviving Britain's exports after the war.

had negotiated throughout the war to liberalise post-war trade and the international flow of capital in order to break into markets which had previously been closed to it, including the British Empire's Pound Sterling

bloc. This was to be realised through the Atlantic Charter

of 1941, through the establishment of the Bretton Woods system

in 1944, and through the new economic power that the US was able to exert due to the weakened British economy.

Immediately after the war had ended, the USA halted Lend-Lease

. This had been fundamental to the sustainability of the British economy during the war and it was expected by the British that it would continue during the period of transition. Instead, the Labour Government under Clement Attlee

sent John Maynard Keynes

to negotiate a loan, known as the Washington Loan Agreement in December 1945 (see Anglo-American loan

). The terms of this were not as favourable as the British had hoped for and included crucially a convertibility clause, in line with the US policy of liberalisation. In this, the USA expected that within two years, the British currency would become fully convertible. This, combined with the fact that the loan wasn't for as much as Keynes had hoped and the 2% interest rate imposed by the Americans, meant that Britain faced an uphill struggle to revive the economy.

The winter of 1946–1947 proved to be very harsh curtailing production and leading to shortages of coal which again affected the economy so that by August 1947 when convertibility was due to begin, the economy was not as strong as it needed to be. When the Labour Government enacted convertibility, there was a run on Sterling, meaning that Sterling was being traded in for dollars, seen as the new, more powerful and stable currency in the world. This damaged the British economy and within weeks it was stopped. By 1949, the British pound was over valued and had to be devalued though this is often considered a measure of last resort for Governments.

The Labour Governments of 1945–1951 enacted a political programme rooted in collectivism

including the nationalisation of industries and state direction of the economy. Both wars had demonstrated the possible benefits of greater state involvement. This underlined the future direction of the post-war economy, and was supported in the main by the Conservatives. However, the initial hopes for nationalisation were not fulfilled and more nuanced understandings of economic management emerged, such as state direction, rather than state ownership. Throughout though, the basis remained the same: applying the economic theories of Keynes and continued state involvement.

Two world wars had taken their toll on the Empire. Decolonisation began with Indian independence in 1947. For many countries formerly part of the Empire, they argued that, in effect, they had won their independence by fighting for Britain during the two wars. However, British power was already shown to be weakened as it became impossible to resist the tide of self determination which ensued. What began under the Labour Government of 1945–1951 was continued under the Conservatives from 1951–1964 with the exception of the Suez Crisis

of 1956. After Suez, the Conservatives made it a central feature of their foreign policy rhetoric with Harold Macmillan

's Wind of Change

speech.

During 1955, unemployment reached a postwar low of just over 215,000 - barely 1% of the workforce.

The loss of the Empire and the material losses incurred through two world wars had affected the basis of Britain’s economy. First, its traditional markets were changing as Commonwealth countries made bilateral trade arrangements with local or regional powers. Second, the initial gains Britain made in the world economy were in relative decline as those countries whose infrastructure was seriously damaged by war repaired these and reclaimed a stake in world markets. Third, the British economy changed structure shifting towards a service sector economy from its manufacturing and industrial origins leaving some regions economically depressed. Finally, part of consensus politics meant support of the Welfare State

and of a world role for Britain; both of these needed funding through taxes and needed a buoyant economy in order to provide the taxes.

Harold Macmillan

"(most of) our people have never had it so good" seemed increasingly hollow. The Conservative Government presided over a ‘stop-go’ economy as it tried to prevent inflation spiralling out of control without snuffing out economic growth. Growth continued to struggle, at about only half the rate of that of Germany or France

at the same time. However, industry had remained strong in nearly 20 years following the end of the war, and extensive housebuilding and construction of new commercial developments and public buildings also helped unemployment stay low throughout this time.

The Labour Party

under Harold Wilson

from 1964–1970 was unable to provide a solution either, and eventually was forced to devalue the Pound

again in 1967. Economist Nicholas Crafts

attributes Britain's relatively low growth in this period to a combination of a lack of competition

in some sectors of the economy, especially in the nationalised industries; poor industrial relations and insufficient vocational training. He writes that this was a period of government failure

caused by poor understanding of economic theory, short-termism and a failure to confront interest groups.

Both political parties had come to the conclusion that Britain needed to enter the European Economic Community

(EEC) in order to revive its economy. This decision came after establishing a European Free Trade Association

(EFTA) with other, non EEC countries since this provided little economic stimulus to Britain’s economy. Levels of trade with the Commonwealth halved in the period 1945–1965 to around 25% while trade with the EEC had doubled during the same period. Charles de Gaulle

vetoed a British attempt at membership in 1963 and again in 1967.

In 1973 the Conservative Prime Minister, Edward Heath

, led Britain into the EEC. As late as this stage, Britain still effectively had full employment, at a rate of 3% unemployed.

However, with the decline of Britain’s economy during the 1960s, the trade unions began to strike leading to a complete breakdown with both the Labour Government of Harold Wilson and later with the Conservative Government of Edward Heath (1970–1974). In the early 1970s, the British economy suffered more as strike action by trade unions, plus the effects of the 1973 oil crisis

, led to a three day week

in 1973-74. In all, over nine million days were lost to strike action under Heath’s Government alone. However, despite a brief period of calm negotiated by the recently re-elected Labour Government of 1974 known as the Social Contract

, a break down with the unions occurred again in 1978, leading to the Winter of Discontent

, and eventually leading to the end of the Labour Government, then being led by James Callaghan

, who had succeeded Wilson in 1976. The extreme industrial strife along with rising inflation and unemployment led Britain to be nicknamed as the "sick man of Europe

."

Unemployment had also risen during this difficult period for the British economy; some 1,500,000 people were now unemployed by 1978, nearly treble the figure at the start of the decade, at a national rate of well over 5%. It had exceeded 1,000,000 since 1975.

Also in the 1970s, oil was found in the North Sea

, off the coast of Scotland.

in 1979 marked the end of the post-war consensus

and a new approach to economic policy, including privatisation and deregulation

,

reform of industrial relations, and tax changes. Competition policy was emphasised instead of industrial policy

; consequent deindustrialisation was more or less accepted. Thatcher's battles with the unions culminated in the Miners' Strike of 1984.

The Government applied monetarist policies to reduce inflation, and reduced public spending. Deflationary measures were implemented against the backdrop of the early 1980s recession

. As a result, unemployment began to rise sharply from early 1980, breaking the 2,000,000 barrier by the end of the year and reaching 2,500,000 during 1981. By January 1982, 3,000,000 were unemployed in Britain for the first time in 50 years, though this time the figure accounted for a lesser percentage of the early 1930s figures, now standing at around 12.5% rather than in excess of 20%. In areas hit particularly hard by the loss of industry, the unemployment rate was much higher; coming to close to 20% in Northern Ireland

and exceeding 15% in many parts of Wales

, Scotland

and northern England.The peak of unemployment actually came some two years after the recession ended and growth had been re-established, when in April 1984 unemployment rose to nearly 3,300,000.

Major state-controlled firms were privatised, including British Aerospace

(1981), British Telecom (1984), British Leyland (1984), Rolls-Royce

(1987), and British Steel

(1988). The electricity, gas and English water industries were split up and sold off. Exchange controls, in operation since the war, were abolished in 1979. British net assets abroad rose approximately ninefold from £12 billion at the end of 1979 to nearly £110 billion at the end of 1986, a record post-war level and second only to Japan. Privatisation of nationalised industries increased share ownership in Britain: the proportion of the adult population owning shares went up from 7% in 1979 to 25% in 1989. The Single European Act

(SEA), signed by Margaret Thatcher, allowed for the free movement of goods within the European Union area. The ostensible benefit of this was to give the spur of competition to the British economy, and increase its ultimate efficiency.

The early 1980s recession saw unemployment rise above three million, but the subsequent recovery, which saw growth of over 4 per cent in the late 1980s, led to contemporary claims of a British 'economic miracle'. It is not clear whether Thatcherism was the only reason for the boom in Britain in the 1980s. However many of the economic policies put in place by the Thatcher governments have been kept since, and even the Labour Party which had once been so opposed to the policies had by the late 1990s, on its return to government after nearly 20 years in opposition, dropped all opposition to them.

By the end of 1986, Britain was enjoying an economic boom, which saw unemployment go into freefall and drop to 1,600,000 by December 1989.

was elected her successor.

Despite several major economies showing quarterly detraction during 1989, the British economy continued to grow well into 1990, with the first quarterly detraction taking place in the third quarter of the year, by which time unemployment was starting to creep upwards again after four years of falling.

Economic growth was not re-established until early 1993, but the Conservative government which had been in power continuously since 1979 managed to achieve re-election in April 1992, fending off a strong challenge from Neil Kinnock and Labour.

The early 1990s recession was officially the longest in Britain since the Great Depression some 60 years earlier, though the fall in output was not as sharp as that of the downturn of the Great Depression or even that of the early 1980s recession. It had started during 1990 and the end of the recession was not officially declared until April 1993, by which time nearly 3,000,000 were unemployed.

The British pound was tied to EU exchange rates, using the Deutsche Mark as a basis, as part of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM); however, this resulted in disaster for Britain. The restrictions imposed by the ERM put pressure on the pound, leading to a run on the currency. Black Wednesday

in 1992 ended British membership of the ERM. It also damaged the credibility of the Conservatives' economic management, and contributed to the end of the 18 years of consecutive Conservative government in 1997.

Despite the downfall of the Conservative government, it had seen a strong economic recovery in which unemployment had fallen by more than 1,000,000 since the end of 1992 to 1,700,000 by the time of their election defeat.

's Labour government stuck with the Conservative's spending plans. The Chancellor

, Gordon Brown

, gained a reputation by some as the "prudent Chancellor" and helped to inspire renewed confidence in Labour's ability to manage the economy. One of the first acts that the new Labour government embarked on was to give the power to set interest rates to the Bank of England

, effectively ending the use of interest rates as a political tool. Labour also introduced the minimum wage

to the United Kingdom

, which has been raised from time to time since its introduction. The Blair government also introduced a number of strategies to cut unemployment. Unemployment fell back to the level it was in the late 1970s, although it still remained significantly higher than it was during the post-war era and the 1960s.

, which they claimed was suffering from chronic under-funding. The economy shifted from manufacturing, which had been declining since the 1980s and grew on the back of the services and finance sectors. The country was also at war with first Afghanistan

, invading in 2001 and then Iraq

, in 2003. Spending on both reached several billion pounds a year.

Growth rates were consistently between 1.6% and 3% from 2000 to early 2008. Inflation though relativity steady at around 2%, did rise in the approach to the financial crash . The Bank of England's control of interest rates was a major factor in the stability of the British economy over that period. The pound

continued to fluctuate, however, reaching a low against the dollar in 2001 (to a rate of $1.37 per £1), but rising again to a rate of approximately $2 per £1 in 2007. Against the Euro, the pound was steady at a rate of approximately €1.45 per £1. Since then, the effects of the Credit crunch

have led to a slowdown of the economy. At the start of November 2008, for example, the pound was worth around €1.26; by the end of the year, it had almost approached parity, dropping at one point below €1.02 and ending the year at €1.04.

since World War 2 in 2008, as part of a global economic downturn. On 5 March 2009, the Bank of England

announced that they would pump £

200 billion of new capital

into the British economy

, through a process known as quantitative easing

. This is the first time in the United Kingdom's history that this measure has been used, although the Bank's Governor

Mervyn King

suggested it was not an experiment.

The process will see the BoE creating new money for itself, which it will then use to purchase assets such as government bonds, bank loans, or mortgages. Despite the misconception that quantitative easing involves printing money, the BoE are unlikely to do this and instead the money will be created electronically and thus not actually enter the cash circulation system. The initial amount to be created through this method will be £75 billion, although former Chancellor of the Exchequer

Alistair Darling

had given permission for up to £150 billion to be created if necessary. It is thought the process is likely to occur over a period of three months with results only likely in the long term.

The BoE has stated that the decision has been taken to prevent the rate of inflation

falling below the two percent target rate. Mervyn King, the Governor of the BoE, also suggested there were no other monetary options left as interest rates had already been cut to their lowest level ever of 0.5% and it was unlikely they would be cut further.

The economy began to climb its way back into growth in late 2009: by Q4 of 2009 with a weak 0.4%; followed by a 0.3% growth in Q1 of 2010, 1.2% in the Q2 then with a 0.7% in the Q3 and the a Contraction of 0.5% in the Q4 making Growth 1.7% in the whole of 2010. Then After growing 0.5% the first quarter regaining that was lost in the Q4 it had lost the chance of double dip recession but had slow growth of 0.3% in the Q2 of 2011.

Economy

An economy consists of the economic system of a country or other area; the labor, capital and land resources; and the manufacturing, trade, distribution, and consumption of goods and services of that area...

of the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

from the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

on May 1st, 1707, with the political union

Political union

A political union is a type of state which is composed of or created out of smaller states. Unlike a personal union, the individual states share a common government and the union is recognized internationally as a single political entity...

of the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

and the Kingdom of Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

. This Union, as well as being political, was designed to be a full economic union, with most of the twenty-five Articles of the Treaty of Union

Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name given to the agreement that led to the creation of the united kingdom of Great Britain, the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, which took effect on 1 May 1707...

dealing with economic arrangements for the new state. In 1801, Great Britain united with Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

.

The United Kingdom developed as one of the world's leading economies. Between 1870 and the end of the 20th century, economic output per head of population in Britain rose by 500 per cent, generating a significant rise in living standards. However, from the late 19th century onwards Britain experienced a relative economic decline when compared to the world's other leading economies. In 1870, Britain's output per head was the second highest in the world after Australia. By 1914, it was fourth highest, having been overtaken. In 1950, British output per head was still 30 per cent ahead of the six founder members of the EEC

EEC

EEC is an abbreviation that usually refers to the European Economic Community, the forerunner to the European Union.It may also refer to;* The East Erie Commercial Railroad, a shortline in Pennsylvania...

, but within 50 years it had been overtaken by many European and several Asian countries.

The Age of Mercantilism

The basis of the British Empire was founded in the age of mercantilismMercantilism

Mercantilism is the economic doctrine in which government control of foreign trade is of paramount importance for ensuring the prosperity and security of the state. In particular, it demands a positive balance of trade. Mercantilism dominated Western European economic policy and discourse from...

, an economic theory that stressed maximizing the trade inside the empire, and trying to weaken rival empires. The modern British Empire was based upon the preceding English Empire which first took shape in the early 17th century, with the English settlement of the eastern colonies of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

, which later became the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, as well as Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

's Maritime provinces, and the colonizations of the smaller islands of the Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

such as Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago is an archipelagic state in the southern Caribbean, lying just off the coast of northeastern Venezuela and south of Grenada in the Lesser Antilles...

, the Bahamas, the Leeward Islands

Leeward Islands

The Leeward Islands are a group of islands in the West Indies. They are the northern islands of the Lesser Antilles chain. As a group they start east of Puerto Rico and reach southward to Dominica. They are situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea meets the western Atlantic Ocean...

, Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

, Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

and Bermuda

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British overseas territory in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located off the east coast of the United States, its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, about to the west-northwest. It is about south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and northeast of Miami, Florida...

. These sugar

Sugar

Sugar is a class of edible crystalline carbohydrates, mainly sucrose, lactose, and fructose, characterized by a sweet flavor.Sucrose in its refined form primarily comes from sugar cane and sugar beet...

plantation islands, where slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

became the basis of the economy, were part of Britain's most important and successful colonies. The American colonies also utilized slave labor in the farming of tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

, cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

, and rice

Rice

Rice is the seed of the monocot plants Oryza sativa or Oryza glaberrima . As a cereal grain, it is the most important staple food for a large part of the world's human population, especially in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and the West Indies...

in the south. Britain's American empire was slowly expanded by war and colonization. Victory over the French during the Seven Years' War

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

gave Britain control over almost all of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

but had only a small economic role.

Mercantilism was the basic policy imposed by Britain on its colonies. Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants--and kept others out--by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximize exports from and minimize imports to the realm. The government had to fight smuggling--which became a favorite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch. The goal of mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a superb Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. Thus the British Navy captured New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam was a 17th-century Dutch colonial settlement that served as the capital of New Netherland. It later became New York City....

(New York) in 1664. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.

.

The Industrial Revolution

In a period loosely dated from the 1770s to the 1820s, Britain experienced an accelerated process of economic change that transformed a largely agrarian economy into the world's first industrial economy. This phenomenon is known as the "industrial revolution", since the changes were all embracing and permanent.It has been argued by historians such as Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, and E.P. Thompson that the foundations of this process of change can be traced back to the Puritan Revolution in the Seventeenth Century. This produced landed and merchant elites alive to the benefits of economic change, and a system of agriculture able to produce increasingly cheap food supplies. To this must be added the influence of religious nonconformity, which increased literacy and inculcated a 'Protestant work ethic

Protestant work ethic

The Protestant work ethic is a concept in sociology, economics and history, attributable to the work of Max Weber...

' amongst skilled artisans.

A long run of good harvests, starting in the first half of the 18th century, resulted in an increase in disposable income and a consequent rising demand for manufactured goods, particularly textiles. The invention of the flying shuttle

Flying shuttle

The flying shuttle was one of the key developments in weaving that helped fuel the Industrial Revolution. It was patented by John Kay in 1733. Only one weaver was needed to control its lever-driven motion. Before the shuttle, a single weaver could not weave a fabric wider than arms length. Beyond...

by John Kay

John Kay (flying shuttle)

John Kay was the inventor of the flying shuttle, which was a key contribution to the Industrial Revolution. He is often confused with his namesake: fellow Lancastrian textile machinery inventor, the unrelated John Kay who built the first "spinning frame".-Life in England:John Kay was born...

enabled wider cloth to be woven faster, but also created a demand for yarn that could not be fulfilled. Thus, the major technological advances associated with the industrial revolution were concerned with spinning. James Hargreaves

James Hargreaves

James Hargreaves was a weaver, carpenter and an inventor in Lancashire, England. He is credited with inventing the spinning Jenny in 1764....

created the Spinning Jenny

Spinning jenny

The spinning jenny is a multi-spool spinning frame. It was invented c. 1764 by James Hargreaves in Stanhill, Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire in England. The device reduced the amount of work needed to produce yarn, with a worker able to work eight or more spools at once. This grew to 120 as technology...

, a device that could perform the work of a number of spinning wheels. However while this invention could be operated by hand, the water frame

Water frame

The water frame is the name given to the spinning frame, when water power is used to drive it. Both are credited to Richard Arkwright who patented the technology in 1768. It was based on an invention by Thomas Highs and the patent was later overturned...

, invented by Richard Arkwright

Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright , was an Englishman who, although the patents were eventually overturned, is often credited for inventing the spinning frame — later renamed the water frame following the transition to water power. He also patented a carding engine that could convert raw cotton into yarn...

, could be powered by a water wheel

Water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of free-flowing or falling water into useful forms of power. A water wheel consists of a large wooden or metal wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving surface...

. Indeed, Arkwright is credited with the widespread introduction of the factory system

Factory system

The factory system was a method of manufacturing first adopted in England at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 1750s and later spread abroad. Fundamentally, each worker created a separate part of the total assembly of a product, thus increasing the efficiency of factories. Workers,...

in Britain, and is the first example of the successful mill owner and industrialist in British history. The water frame was, however, soon supplanted by the spinning mule

Spinning mule

The spinning mule was a machine used to spin cotton and other fibres in the mills of Lancashire and elsewhere from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century. Mules were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of two boys: the little piecer and the big or side piecer...

(a cross between a water frame and a jenny) invented by Samuel Crompton

Samuel Crompton

Samuel Crompton was an English inventor and pioneer of the spinning industry.- Early life :Samuel Crompton was born at 10 Firwood Fold, Bolton, Lancashire to George and Betty Crompton . Samuel had two younger sisters...

. Mules were later constructed in iron by Messrs. Horrocks of Stockport.

As they were water powered, the first mills were constructed in rural locations by streams or rivers. Workers villages were created around them. Styal Mill (owned by the National Trust

National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, usually known as the National Trust, is a conservation organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

) is a surviving example of this kind of enterprise, as are New Lanark

New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles from Lanark, in South Lanarkshire, Scotland. It was founded in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and housing for the mill workers. Dale built the mills there to take advantage of the water power provided by the river...

Mills in Scotland. These spinning mills resulted in the decline of the domestic system, in which spinning was undertaken in rural cottages.

However, the textile trade was transformed, as was much else, by the development of the steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

. The first practicable steam engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen