Dunster Castle

Encyclopedia

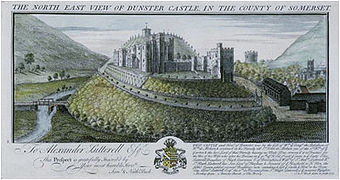

Dunster Castle is a former motte and bailey castle, now a country house, in the village of Dunster

, Somerset

, England. The castle lies on the top of a steep hill called the Tor, and has been fortified since the late Anglo-Saxon

period. After the Norman conquest of England

in the 11th century, William de Mohun constructed a timber castle on the site as part of the pacification of Somerset. A stone shell keep

was built on the motte by the start of the 12th century, and the castle survived a siege during the early years of the Anarchy

. At the end of the 14th century the de Mohuns sold the castle to the Luttrell family

, who continued to occupy the property until the late 20th century.

The castle was expanded several times by the Luttrell family during the 17th and 18th centuries; they built a large manor house

within the Lower Ward of the castle in 1617, and this was extensively modernised, first during the 1680s and then during the 1760s. The medieval castle walls were mostly destroyed following the siege of Dunster Castle at the end of the English Civil War

, when Parliament

ordered the defences to be slighted

to prevent their further use. In the 1860s and 1870s, the architect Anthony Salvin

was employed to remodel the castle to fit Victorian tastes; this work extensively changed the appearance of Dunster to make it appear more Gothic

and Picturesque

.

Following the death of Alexander Luttrell in 1944, the family was unable to afford the death duties

on his estate. The castle and surrounding lands were sold off to a property firm, the family continuing to live in the castle as tenants. The Luttrells bought back the castle in 1954, but in 1976 Colonel Walter Luttrell gave Dunster Castle and most of its contents to the National Trust

. As of 2011 the castle is operated by the trust as a tourist attraction

; it is a Grade I listed building and scheduled monument.

in Somerset

. During the early medieval period the sea reached the base of the hill, close to the mouth of the River Avill

, offering a natural defence and making the village an inland port. Several Iron Age

hillforts were built close to Dunster, including Bat's Castle

, Black Ball Camp

and Grabbist Hill, but the earliest evidence of a fortification at Dunster was an Anglo-Saxon

burgh

. This was built on the summit of the hill and was possibly intended to protect the region against sea-borne raiders; by the mid-11th century it was controlled by a local nobleman called Aelfric.

In 1066 the Normans invaded south-east England, defeating the English forces at the battle of Hastings

: in the aftermath of the victory, William the Conqueror entrusted the conquest of the south-west of England to his half-brother Robert of Mortain. Expecting stiff resistance, Robert marched west into Somerset, supported by forces under Walter of Douai

, who entered from the north; a third force, under the command of William de Mohun, landed by sea along the Somerset coast. William had been granted 68 manors in the region and by 1086 had established a castle at Dunster; this would form both the caput, or principal castle, for his new lands, and help guard the coast against the threat of any fresh sea-borne attack, as well as controlling the coastal road running from Somerset to Gloucestershire

. This first castle was a motte and bailey design, built upon the former Anglo-Saxon burgh; the top of the Tor was scarped

to form the motte, or Upper Ward, and an area below shaped to form the bailey, or Lower Ward.

Somerset became more stable in the aftermath of the post-invasion period and the unsuccessful 1068 rebellion against Norman rule. It was common in the period for the Normans to build religious houses to accompany major castles, and accordingly William de Mohun endowed a Benedictine

priory

at Dunster in 1090, along with its parent abbey at Bath

. The River Avill was important for trade; the region around Dunster was rich with fisheries

and vineyard

s, and Dunster Castle prospered. Stone fortifications were built on the site during the early 12th century, probably forming a shell keep

around the top of the motte.

In the late 1130s England began to descend into a period of civil war known as the Anarchy

, during which the supporters of King Stephen

fought with those of the Empress Matilda

for control of the kingdom. William de Mohun's eldest son, also called William, was a noted supporter of Matilda, and Dunster was considered one of her faction's strongest castles in the south-west. In 1138 forces loyal to Stephen besieged the castle; a siege castle was built nearby, but all trace of it has been lost. William successfully held the castle and was made the Earl of Somerset by the grateful Empress. Chroniclers subsequently complained of the way in which he subsequently raided and controlled the region by force during the war, causing much destruction. In the aftermath of the conflict, William's son, another William, inherited the castle after a short period of royal ownership under Henry II

. William appears to have insisted that his tenants agree to help repair and maintain the castle walls as part of their feudal service.

and a knight's hall, guarded by three towers. The Lower Ward included a granary

, two towers and a gatehouse; one of the towers, called the Fleming Tower, was used as a prison. The castle stables lay outside the defences, further down the slope. By the end of the 13th century some of the castle's roofing had been covered in lead, while other parts still used wooden shingles.

In 1330 Sir John de Mohun

inherited the castle; John, although a notable knight, was childless and fell into considerable debt. His wife Joan took over the running of their estates, and when John died in 1376 she agreed to sell the castle to Lady Elizabeth Luttrell, the leading member of another major Norman family, for 5,000 mark

s, with the castle to transfer to Elizabeth on Joan's death. At some point during this period additional stone buildings were constructed along the Lower Ward, on the side of the current mansion, and records suggest that a ditch, or moat

, may have existed around the base of the Tor in the 14th century.

Joan outlived Elizabeth, and in the event Sir Hugh Luttrell, who was Henry V's

seneschal

in Normandy

, finally took over the castle on Joan's death in 1404. The castle had suffered from a lack of investment during the final years of the Mohan's ownership, and Luttrell repaired and extended the castle at a cost of £252, constructing the Great Gatehouse and a barbican

between 1419 and 1424. The new entrance lay at right-angles to the old and was three storeys high, built of imported Bristol red sandstone

, and contained extensive apartments; it formed a grand, if ill-defended, ceremonial route into the castle. The castle was reroofed with Cornish

stone tiles. By the 15th century the sea had receded, and the Luttrells created a deer park

for the castle at Marshwood. Such a park would have been highly prestigious and allowed the Luttrell's to engage in hunting

, providing the castle with a supply of venison

as well as generating income.

During the 15th century, England was divided by the prolonged period of civil war called the Wars of the Roses

: the Luttrells were supporters of the House of Lancaster

. In 1461, Sir James Luttrell died following the Lancastrian defeat at the Second Battle of St Albans

, and his family were deprived of their estates by the Yorkist Edward IV

. The castle was given to the Herberts, but the Luttrells regained it on the accession of the Lancastarian Henry VII

in 1485, when Dunster was restored to James' son, Sir Hugh Luttrell. Hugh repaired the castle chapel and in the early 16th century his son, Sir Andrew Luttrell, built a new wall on the east side of the castle. Andrew's son John Luttrell

, who inherited the castle, was a famous soldier, diplomat

, and courtier

under Henry VIII

and Edward VI

, serving in France and in Scotland during the conflicts of the Rough Wooing

.

In 1542 the antiquarian

John Leland reported the castle keep and buildings to be considerable disrepair, with the exception of the chapel, and by the time Sir George Luttrell inherited in 1571 the castle was dilapidated, with the family preferring to live in their house at East Quantoxhead

. In 1617 Sir George employed the architect William Arnold

to create a new house in the Lower Ward of the castle; Arnold was an important architect in the south-west of England, and had managed the building of Montacute

and Cranborne House

. The redesign expanded on some of the existing buildings and walls to create a 16th-century Jacobean

mansion with a symmetrical front and square towers, set within the older castle walls and overlooked by the keep above. The building was decorated in the latest styles, including ornamental plaster ceilings. The project ran almost three times over budget, costing Luttrell more than £1,200.

broke out between the supporters of King Charles I

and Parliament

. Thomas Luttrell supported Parliament and after the outbreak of war William Russell

, the Duke of Bedford

and Parliamentary commander in Devon and Somerset, ordered him to increase the garrison at Dunster to resist a potential Royalist attack. The Royalist commander William Seymour

, the Duke of Somerset

, attacked the castle in 1642 but was driven back by the garrison, led by Thomas' wife, Jane. The war in the south-west turned in favour of the King, and on 7 June 1643 the Royalists mustered forces to attack the castle again: this time Luttrell surrendered, switching sides to support the Royalists until his death the following February. Colonel Wyndham

was appointed the Royalist governor of the castle. The young Prince Charles, the later Charles II

, stayed at the castle in May 1645.

During 1645 the Royalist military cause largely collapsed, and Colonel Robert Blake

led a Parliamentary force against Dunster in October. In November Blake began his siege of the castle, setting up his artillery in Dunster village and starting to dig tunnels to plant mines beneath the walls. The castle was briefly relieved by reinforcements in February 1646, but the siege was resumed and by April the Royalists situation was untenable – an honourable surrender was negotiated and a Parliamentary garrison installed. After the end of the Second English Civil War

in 1649, however, Parliament decided to deliberately destroy, or slight

, the defences of castles in key Royalist areas, including the south-west. In the case of Dunster, Thomas's son George Luttrell was able to convince the authorities to destroy only the medieval defensive walls, rather than the entire castle, leaving Dunster damaged from the recent siege but still habitable; the walls were demolished over 12 days in August 1650 by a team of 300 workmen. The only parts of the medieval walls to survive were the Great Gatehouse and the bases of the two towers in the Lower Ward.

George Luttrell died without children, and Dunster Castle passed to his brother Francis, who survived the political turmoil of both the Commonwealth

years and the Restoration

of Charles II to power in 1660. Francis' heir, another Francis, married a wealthy heiress worth £2,500 a year (£331,000 at 2009 prices) and with this income set about modernising the castle during the 1680s, in particular building a grand staircase in the latest style. Francis was a colonel in the local militia and in 1688 backed William of Orange

's attempt to oust

James II

; when William landed in Devon, Francis mustered a number of companies of infantry at Dunster on 19 November to support him, which formed the basis for the later Green Howards regiment. During this period the castle still kept an armoury of 43 musket

s. Francis died heavily in debt in 1690, and his widow Mary moved the contents of the castle to London, where they were destroyed in a fire in 1696.

At the start of the 18th century the Luttrells and Dunster Castle faced many financial challenges. Alexander, Francis's son, inherited the castle in 1704, but it was still mostly empty and carried large debts with it. Alexander died young and his widow, Dorothy, spent almost twenty years paying off the debts. Dorothy built a new chapel, designed by Sir James Thornhill

At the start of the 18th century the Luttrells and Dunster Castle faced many financial challenges. Alexander, Francis's son, inherited the castle in 1704, but it was still mostly empty and carried large debts with it. Alexander died young and his widow, Dorothy, spent almost twenty years paying off the debts. Dorothy built a new chapel, designed by Sir James Thornhill

in white Portland stone

, on the rear of the mansion at a cost of £1,300 (£178,000 at 2009 prices); few records of this remain, but the interior probably resembled that of the chapel at Wimpole Hall

. A safer, if less grand, approach road to the castle was created, called the New Way, and the remains of the Upper Ward on top of the motte were flattened to be used as a bowling green

, complete with an octagonal summer house

. Dorothy's son, Alexander Luttrell, took over the castle in 1726 but ran up new debts, and the castle was handed over into the control of a receiver

.

Henry Luttrell, who married Alexander's daughter and took the Luttrell name, moved to Dunster in 1747. The couple redesigned and redecorated the castle in a Rococo style, including the extensive use of the recently invented and highly fashionable wallpaper

. Henry Luttrell raised the ground height of the Lower Ward between 1764 and 1765 to extend the New Way all around to the front of his mansion, adding additional ornamental towers onto the inside of the Great Gatehouse in the process. A folly

, Conygar Tower

, was constructed by architect Richard Phelps to improve the view from the castle, and a larger park of 141 hectares (348 acres) was built just to the south of the castle, requiring the eviction of a number of tenant farmers.

George Luttrell inherited the castle in 1867 and began an extensive modernisation, backed by the considerable income from the Dunster estates – in a period of agricultural boom

in England, the estates were producing £22,000 in revenue a year (£1.49 million at 2010 prices). It was fashionable during the mid-Victorian

period to remodel existing castles to produce what was felt to be a more consistent Gothic or sometimes Picturesque appearance and George, a keen historian, decided to follow this trend at Dunster; in the process, he also hoped to accommodate the larger household and facilities required for a 19th-century landowner: by 1881, the castle required 15 "living-in" servants alone. He employed Anthony Salvin

, a noted architect then most famous for his work at Alnwick Castle

, to carry out the work between 1868 and 1872 at a total cost of £25,350 (equivalent to £1.76 million as of 2010).

Salvin aimed to create a castle that would appear to have grown up organically over time, but still appeal to Victorian aesthetic taste. Accordingly, a large, square tower was built on the west side of the castle and another smaller tower on the east, both creating additional space but also making the castle deliberately asymmetrical. The 18th-century chapel at the rear was demolished and replaced with another tower, alongside a modern conservatory

. A variety of windows in the styles of different historical periods were inserted in the walls, while modern Victorian technology, including gas lighting

-supported by a gas

plant

in the basement-central heating and new kitchens were installed within the castle. The roof of the Great Gatehouse was raised to create a more uniform sequence of battlements, and a large hall for gatherings of the local farmers installed. A new wing of servants' quarters and offices were sunk into the hill, spread over two floors leading away from the main part of the mansion.

Internally, Salvin knocked through existing rooms to create the Outer Hall, a new gallery on the first floor, a billiard room, a new library and a drawing room. Much of the wooden 17th-century panelling in the parlour and the hall had to be stripped out as part of the renovations. As part of his work, Salvin appears to have used a number of rolled wrought-iron beams to span the resulting structural gaps in the building, an advanced use of that technology for the time. The house was refurnished with newly bought 16th and 17th-century artwork, two brass

Italian cannon

s and a stuffed polar bear

.

Alexander Luttrell, who inherited Dunster Castle in 1910, chose to live at East Quantoxhead instead, and it was left empty until his son Geoffrey reoccupied the castle in 1920, redecorating some of the rooms in a contemporary style and building a polo

ground alongside the castle. The castle and the surrounding countryside at this time was very popular with the Luttrells for fox hunting

and shooting

. During the Second World War the castle was used as a convalescent home for injured naval and American officers between 1943 and 1944.

Alexander died in 1944, and the death duties

proved crippling to Geoffrey. In 1949 he sold the castle and 3,480 hectares (8,600 acres) of the lands to the Ashdale Property Company, retaining a tenancy of the castle for himself. The Crown Estate

bought the estate from Ashdale and sold the castle back to Geoffrey in 1954. His son Colonel Walter Luttrell lived away from Dunster, and following the death of his mother – the last Luttrell to live in the property – gave the castle and most of its contents to the National Trust

in 1976.

. Little remains of the medieval castle except for the Great Gatehouse and the remains of several towers in the Lower Ward; the heart of the modern castle today is the much altered 17th-century manor house. The key features of the castle include the original 13th-century gates and several pieces of art, including a Tudor copy of Hans Eworth

's famous allegorical portrait of Sir John Luttrell

, and a sequence of leather tapestries

showing scenes from the story of Antony and Cleopatra

. The gardens surrounding the castle cover approximately 6 hectares (14.8 acre) and include the National Plant Collection

of Strawberry Trees; the wider parkland beyond totals 277 hectares (684.5 acre). Just to the south of the castle is the restored 18th-century castle watermill

. In 2010 the castle received 128,242 visitors.

Dunster Castle has been designated by English Heritage

as a Grade I listed building and Scheduled Ancient Monument

. The castle has required continuing maintenance work, in particular to its roof, itself an important historical feature. Efforts have been made to gradually redecorate the castle in a period style, using reproductions of original wallpapers and materials. The National Trust installed solar panels behind the battlements on the roof in 2008 to provide electricity and make the premises more environmentally friendly. This was the first time the National Trust have taken this approach to a Grade I listed building, and it is expected to save 1,714 kg (3,778 lb) of carbon

a year.

Dunster

Dunster is a village and civil parish in west Somerset, England, situated on the Bristol Channel coast south-southeast of Minehead and northwest of Taunton. The village has a population of 862 .The village has numerous restaurants and three pubs...

, Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, England. The castle lies on the top of a steep hill called the Tor, and has been fortified since the late Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxon may refer to:* Anglo-Saxons, a group that invaded Britain** Old English, their language** Anglo-Saxon England, their history, one of various ships* White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, an ethnicity* Anglo-Saxon economy, modern macroeconomic term...

period. After the Norman conquest of England

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

in the 11th century, William de Mohun constructed a timber castle on the site as part of the pacification of Somerset. A stone shell keep

Shell keep

A shell keep is a style of medieval fortification, best described as a stone structure circling the top of a motte.In English castle morphology, shell keeps are perceived as the successors to motte-and-bailey castles, with the wooden fence around the top of the motte replaced by a stone wall...

was built on the motte by the start of the 12th century, and the castle survived a siege during the early years of the Anarchy

The Anarchy

The Anarchy or The Nineteen-Year Winter was a period of English history during the reign of King Stephen, which was characterised by civil war and unsettled government...

. At the end of the 14th century the de Mohuns sold the castle to the Luttrell family

Earl of Carhampton

Earl of Carhampton was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1785 for Simon Luttrell, 1st Viscount Carhampton. He had already been created Baron Irnham, of Luttrellstown in the County of Dublin, in 1768 and Viscount Carhampton, of Castlehaven in the County of Cork, in 1781, also in...

, who continued to occupy the property until the late 20th century.

The castle was expanded several times by the Luttrell family during the 17th and 18th centuries; they built a large manor house

Manor house

A manor house is a country house that historically formed the administrative centre of a manor, the lowest unit of territorial organisation in the feudal system in Europe. The term is applied to country houses that belonged to the gentry and other grand stately homes...

within the Lower Ward of the castle in 1617, and this was extensively modernised, first during the 1680s and then during the 1760s. The medieval castle walls were mostly destroyed following the siege of Dunster Castle at the end of the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, when Parliament

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

ordered the defences to be slighted

Slighting

A slighting is the deliberate destruction, partial or complete, of a fortification without opposition. During the English Civil War this was to render it unusable as a fort.-Middle Ages:...

to prevent their further use. In the 1860s and 1870s, the architect Anthony Salvin

Anthony Salvin

Anthony Salvin was an English architect. He gained a reputation as an expert on medieval buildings and applied this expertise to his new buildings and his restorations...

was employed to remodel the castle to fit Victorian tastes; this work extensively changed the appearance of Dunster to make it appear more Gothic

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture....

and Picturesque

Picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year 1770, a practical book which instructed England's...

.

Following the death of Alexander Luttrell in 1944, the family was unable to afford the death duties

Inheritance tax

An inheritance tax or estate tax is a levy paid by a person who inherits money or property or a tax on the estate of a person who has died...

on his estate. The castle and surrounding lands were sold off to a property firm, the family continuing to live in the castle as tenants. The Luttrells bought back the castle in 1954, but in 1976 Colonel Walter Luttrell gave Dunster Castle and most of its contents to the National Trust

National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, usually known as the National Trust, is a conservation organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

. As of 2011 the castle is operated by the trust as a tourist attraction

Tourist attraction

A tourist attraction is a place of interest where tourists visit, typically for its inherent or exhibited cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, or amusement opportunities....

; it is a Grade I listed building and scheduled monument.

11th to 12th centuries

Dunster Castle was positioned on a steep, 200 feet (61 m) high hill, sometimes called the Tor, overlooking the village of DunsterDunster

Dunster is a village and civil parish in west Somerset, England, situated on the Bristol Channel coast south-southeast of Minehead and northwest of Taunton. The village has a population of 862 .The village has numerous restaurants and three pubs...

in Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

. During the early medieval period the sea reached the base of the hill, close to the mouth of the River Avill

River Avill

The River Avill is a small river on Exmoor in Somerset, England.It rises on the eastern slopes of Dunkery Beacon and flows north through Timberscombe and Dunster flowing into the Bristol Channel at Dunster Beach....

, offering a natural defence and making the village an inland port. Several Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

hillforts were built close to Dunster, including Bat's Castle

Bat's Castle

Bats Castle is an Iron Age hill fort at the top of a high hill in the parish of Carhampton south south west of Dunster in Somerset, England.The site was identified in 1983 after some schoolboys found eight silver plated coins dating from 102BC to AD350....

, Black Ball Camp

Black Ball Camp

Black Ball Camp is an Iron Age hill fort South West of Dunster, Somerset, England on the northern summit of Gallox Hill. It is a Scheduled Ancient Monument....

and Grabbist Hill, but the earliest evidence of a fortification at Dunster was an Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxon may refer to:* Anglo-Saxons, a group that invaded Britain** Old English, their language** Anglo-Saxon England, their history, one of various ships* White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, an ethnicity* Anglo-Saxon economy, modern macroeconomic term...

burgh

Burgh

A burgh was an autonomous corporate entity in Scotland and Northern England, usually a town. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Burgh status was broadly analogous to borough status, found in the rest of the United...

. This was built on the summit of the hill and was possibly intended to protect the region against sea-borne raiders; by the mid-11th century it was controlled by a local nobleman called Aelfric.

In 1066 the Normans invaded south-east England, defeating the English forces at the battle of Hastings

Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings occurred on 14 October 1066 during the Norman conquest of England, between the Norman-French army of Duke William II of Normandy and the English army under King Harold II...

: in the aftermath of the victory, William the Conqueror entrusted the conquest of the south-west of England to his half-brother Robert of Mortain. Expecting stiff resistance, Robert marched west into Somerset, supported by forces under Walter of Douai

Walter of Douai

Walter of Douai was a Norman knight, probably at the Battle of Hastings, and a major landowner in South West England after the Norman Conquest. He is given various names and titles in different sources including: Walter de Douai. Douai is sometimes written as Dowai...

, who entered from the north; a third force, under the command of William de Mohun, landed by sea along the Somerset coast. William had been granted 68 manors in the region and by 1086 had established a castle at Dunster; this would form both the caput, or principal castle, for his new lands, and help guard the coast against the threat of any fresh sea-borne attack, as well as controlling the coastal road running from Somerset to Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn, and the entire Forest of Dean....

. This first castle was a motte and bailey design, built upon the former Anglo-Saxon burgh; the top of the Tor was scarped

Counterscarp

A scarp and a counterscarp are the inner and outer sides of a ditch used in fortifications. In permanent fortifications the scarp and counterscarp may be encased in stone...

to form the motte, or Upper Ward, and an area below shaped to form the bailey, or Lower Ward.

Somerset became more stable in the aftermath of the post-invasion period and the unsuccessful 1068 rebellion against Norman rule. It was common in the period for the Normans to build religious houses to accompany major castles, and accordingly William de Mohun endowed a Benedictine

Benedictine

Benedictine refers to the spirituality and consecrated life in accordance with the Rule of St Benedict, written by Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century for the cenobitic communities he founded in central Italy. The most notable of these is Monte Cassino, the first monastery founded by Benedict...

priory

Priory

A priory is a house of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or religious sisters , or monasteries of monks or nuns .The Benedictines and their offshoots , the Premonstratensians, and the...

at Dunster in 1090, along with its parent abbey at Bath

Bath Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Bath, commonly known as Bath Abbey, is an Anglican parish church and a former Benedictine monastery in Bath, Somerset, England...

. The River Avill was important for trade; the region around Dunster was rich with fisheries

Fishery

Generally, a fishery is an entity engaged in raising or harvesting fish which is determined by some authority to be a fishery. According to the FAO, a fishery is typically defined in terms of the "people involved, species or type of fish, area of water or seabed, method of fishing, class of boats,...

and vineyard

Vineyard

A vineyard is a plantation of grape-bearing vines, grown mainly for winemaking, but also raisins, table grapes and non-alcoholic grape juice...

s, and Dunster Castle prospered. Stone fortifications were built on the site during the early 12th century, probably forming a shell keep

Shell keep

A shell keep is a style of medieval fortification, best described as a stone structure circling the top of a motte.In English castle morphology, shell keeps are perceived as the successors to motte-and-bailey castles, with the wooden fence around the top of the motte replaced by a stone wall...

around the top of the motte.

In the late 1130s England began to descend into a period of civil war known as the Anarchy

The Anarchy

The Anarchy or The Nineteen-Year Winter was a period of English history during the reign of King Stephen, which was characterised by civil war and unsettled government...

, during which the supporters of King Stephen

Stephen of England

Stephen , often referred to as Stephen of Blois , was a grandson of William the Conqueror. He was King of England from 1135 to his death, and also the Count of Boulogne by right of his wife. Stephen's reign was marked by the Anarchy, a civil war with his cousin and rival, the Empress Matilda...

fought with those of the Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda , also known as Matilda of England or Maude, was the daughter and heir of King Henry I of England. Matilda and her younger brother, William Adelin, were the only legitimate children of King Henry to survive to adulthood...

for control of the kingdom. William de Mohun's eldest son, also called William, was a noted supporter of Matilda, and Dunster was considered one of her faction's strongest castles in the south-west. In 1138 forces loyal to Stephen besieged the castle; a siege castle was built nearby, but all trace of it has been lost. William successfully held the castle and was made the Earl of Somerset by the grateful Empress. Chroniclers subsequently complained of the way in which he subsequently raided and controlled the region by force during the war, causing much destruction. In the aftermath of the conflict, William's son, another William, inherited the castle after a short period of royal ownership under Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

. William appears to have insisted that his tenants agree to help repair and maintain the castle walls as part of their feudal service.

13th to 17th centuries

In the 13th century the Lower Ward was rebuilt in stone by Reynold Mohun; this was paid for in part by Reynold commuting his tenants' ongoing duty to repair the castle walls into a single, one-off financial payment to their lord, and partially through his marriage to a rich local heiress. A survey of the castle in 1266 described the Upper Ward on the top of the motte as containing a hall with a buttery, a pantry, a kitchen, a bakehouse, the chapel of Saint StephenSaint Stephen

Saint Stephen The Protomartyr , the protomartyr of Christianity, is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Churches....

and a knight's hall, guarded by three towers. The Lower Ward included a granary

Granary

A granary is a storehouse for threshed grain or animal feed. In ancient or primitive granaries, pottery is the most common use of storage in these buildings. Granaries are often built above the ground to keep the stored food away from mice and other animals.-Early origins:From ancient times grain...

, two towers and a gatehouse; one of the towers, called the Fleming Tower, was used as a prison. The castle stables lay outside the defences, further down the slope. By the end of the 13th century some of the castle's roofing had been covered in lead, while other parts still used wooden shingles.

In 1330 Sir John de Mohun

John de Mohun, 2nd Baron Mohun

John de Mohun, 2nd Baron Mohun, 9th Baron de Mohun of Dunster, KG was a founder member and the 11th Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter in 1348....

inherited the castle; John, although a notable knight, was childless and fell into considerable debt. His wife Joan took over the running of their estates, and when John died in 1376 she agreed to sell the castle to Lady Elizabeth Luttrell, the leading member of another major Norman family, for 5,000 mark

Mark (money)

Mark was a measure of weight mainly for gold and silver, commonly used throughout western Europe and often equivalent to 8 ounces. Considerable variations, however, occurred throughout the Middle Ages Mark (from a merging of three Teutonic/Germanic languages words, Latinized in 9th century...

s, with the castle to transfer to Elizabeth on Joan's death. At some point during this period additional stone buildings were constructed along the Lower Ward, on the side of the current mansion, and records suggest that a ditch, or moat

Moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that surrounds a castle, other building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive water defences, including natural or artificial lakes, dams and sluices...

, may have existed around the base of the Tor in the 14th century.

Joan outlived Elizabeth, and in the event Sir Hugh Luttrell, who was Henry V's

Henry V of England

Henry V was King of England from 1413 until his death at the age of 35 in 1422. He was the second monarch belonging to the House of Lancaster....

seneschal

Seneschal

A seneschal was an officer in the houses of important nobles in the Middle Ages. In the French administrative system of the Middle Ages, the sénéchal was also a royal officer in charge of justice and control of the administration in southern provinces, equivalent to the northern French bailli...

in Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

, finally took over the castle on Joan's death in 1404. The castle had suffered from a lack of investment during the final years of the Mohan's ownership, and Luttrell repaired and extended the castle at a cost of £252, constructing the Great Gatehouse and a barbican

Barbican

A barbican, from medieval Latin barbecana, signifying the "outer fortification of a city or castle," with cognates in the Romance languages A barbican, from medieval Latin barbecana, signifying the "outer fortification of a city or castle," with cognates in the Romance languages A barbican, from...

between 1419 and 1424. The new entrance lay at right-angles to the old and was three storeys high, built of imported Bristol red sandstone

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

, and contained extensive apartments; it formed a grand, if ill-defended, ceremonial route into the castle. The castle was reroofed with Cornish

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

stone tiles. By the 15th century the sea had receded, and the Luttrells created a deer park

Medieval deer park

A medieval deer park was an enclosed area containing deer. It was bounded by a ditch and bank with a wooden park pale on top of the bank. The ditch was typically on the inside, thus allowing deer to enter the park but preventing them from leaving.-History:...

for the castle at Marshwood. Such a park would have been highly prestigious and allowed the Luttrell's to engage in hunting

Hunting

Hunting is the practice of pursuing any living thing, usually wildlife, for food, recreation, or trade. In present-day use, the term refers to lawful hunting, as distinguished from poaching, which is the killing, trapping or capture of the hunted species contrary to applicable law...

, providing the castle with a supply of venison

Venison

Venison is the meat of a game animal, especially a deer but also other animals such as antelope, wild boar, etc.-Etymology:The word derives from the Latin vēnor...

as well as generating income.

During the 15th century, England was divided by the prolonged period of civil war called the Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses were a series of dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York...

: the Luttrells were supporters of the House of Lancaster

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. It was one of the opposing factions involved in the Wars of the Roses, an intermittent civil war which affected England and Wales during the 15th century...

. In 1461, Sir James Luttrell died following the Lancastrian defeat at the Second Battle of St Albans

Second Battle of St Albans

The Second Battle of St Albans was a battle of the English Wars of the Roses fought on 17 February, 1461, at St Albans. The army of the Yorkist faction under the Earl of Warwick attempted to bar the road to London north of the town. The rival Lancastrian army used a wide outflanking manoeuvre to...

, and his family were deprived of their estates by the Yorkist Edward IV

Edward IV of England

Edward IV was King of England from 4 March 1461 until 3 October 1470, and again from 11 April 1471 until his death. He was the first Yorkist King of England...

. The castle was given to the Herberts, but the Luttrells regained it on the accession of the Lancastarian Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

in 1485, when Dunster was restored to James' son, Sir Hugh Luttrell. Hugh repaired the castle chapel and in the early 16th century his son, Sir Andrew Luttrell, built a new wall on the east side of the castle. Andrew's son John Luttrell

John Luttrell (soldier)

Sir John Luttrell was an English soldier, diplomat, and courtier under Henry VIII and Edward VI. He served under Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford in Scotland and France...

, who inherited the castle, was a famous soldier, diplomat

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

, and courtier

Courtier

A courtier is a person who is often in attendance at the court of a king or other royal personage. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the residence of the monarch, and social and political life were often completely mixed together...

under Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

and Edward VI

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

, serving in France and in Scotland during the conflicts of the Rough Wooing

The Rough Wooing

The War of the Rough Wooing was fought between Scotland and England. War was declared by Henry VIII of England, in an attempt to force the Scots to agree to a marriage between his son Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Scotland benefited from French military aid. Edward VI continued the war until...

.

In 1542 the antiquarian

Antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient objects of art or science, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts...

John Leland reported the castle keep and buildings to be considerable disrepair, with the exception of the chapel, and by the time Sir George Luttrell inherited in 1571 the castle was dilapidated, with the family preferring to live in their house at East Quantoxhead

East Quantoxhead

East Quantoxhead is a village in West Somerset, from West Quantoxhead, east of Williton, and west of Bridgwater, within the Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in Somerset, England.-History:...

. In 1617 Sir George employed the architect William Arnold

William Arnold (architect)

William Arnold was an important master mason in Somerset, England.Little is known about him, but he is known to have been living in Charlton Musgrove near Wincanton in 1595 where he was church warden. His first known commission was for the design of Montacute House in c1598...

to create a new house in the Lower Ward of the castle; Arnold was an important architect in the south-west of England, and had managed the building of Montacute

Montacute House

Montacute House is a late Elizabethan country house situated in the South Somerset village of Montacute. This house is a textbook example of English architecture during a period that was moving from the medieval Gothic to the Renaissance Classical; this has resulted in Montacute being regarded as...

and Cranborne House

Cranborne Manor

Cranborne Manor is a grade I listed country house in the county of Dorset in southern England.The manor dates back to the thirteenth century, and was originally a hunting lodge. It was remodelled for the 1st Earl of Salisbury in the early 17th century...

. The redesign expanded on some of the existing buildings and walls to create a 16th-century Jacobean

Jacobean architecture

The Jacobean style is the second phase of Renaissance architecture in England, following the Elizabethan style. It is named after King James I of England, with whose reign it is associated.-Characteristics:...

mansion with a symmetrical front and square towers, set within the older castle walls and overlooked by the keep above. The building was decorated in the latest styles, including ornamental plaster ceilings. The project ran almost three times over budget, costing Luttrell more than £1,200.

English Civil War and the Restoration

In the 1640s the English Civil WarEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

broke out between the supporters of King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

and Parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

. Thomas Luttrell supported Parliament and after the outbreak of war William Russell

William Russell, 1st Duke of Bedford

William Russell, 1st Duke of Bedford KG PC was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640 until 1641 when he inherited his Peerage and sat in the House of Lords...

, the Duke of Bedford

Duke of Bedford

thumb|right|240px|William Russell, 1st Duke of BedfordDuke of Bedford is a title that has been created five times in the Peerage of England. The first creation came in 1414 in favour of Henry IV's third son, John, who later served as regent of France. He was made Earl of Kendal at the same time...

and Parliamentary commander in Devon and Somerset, ordered him to increase the garrison at Dunster to resist a potential Royalist attack. The Royalist commander William Seymour

William Seymour, 2nd Duke of Somerset

Sir William Seymour, 2nd Duke of Somerset, KG was an English nobleman and Royalist commander in the English Civil War....

, the Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset is a title in the peerage of England that has been created several times. Derived from Somerset, it is particularly associated with two families; the Beauforts who held the title from the creation of 1448 and the Seymours, from the creation of 1547 and in whose name the title is...

, attacked the castle in 1642 but was driven back by the garrison, led by Thomas' wife, Jane. The war in the south-west turned in favour of the King, and on 7 June 1643 the Royalists mustered forces to attack the castle again: this time Luttrell surrendered, switching sides to support the Royalists until his death the following February. Colonel Wyndham

Sir Francis Wyndham, 1st Baronet

Sir Francis Wyndham, 1st Baronet was an English soldier and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England in 1640...

was appointed the Royalist governor of the castle. The young Prince Charles, the later Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

, stayed at the castle in May 1645.

During 1645 the Royalist military cause largely collapsed, and Colonel Robert Blake

Robert Blake (admiral)

Robert Blake was one of the most important military commanders of the Commonwealth of England and one of the most famous English admirals of the 17th century. Blake is recognised as the chief founder of England's naval supremacy, a dominance subsequently inherited by the British Royal Navy into...

led a Parliamentary force against Dunster in October. In November Blake began his siege of the castle, setting up his artillery in Dunster village and starting to dig tunnels to plant mines beneath the walls. The castle was briefly relieved by reinforcements in February 1646, but the siege was resumed and by April the Royalists situation was untenable – an honourable surrender was negotiated and a Parliamentary garrison installed. After the end of the Second English Civil War

Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War was the second of three wars known as the English Civil War which refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1652 and also include the First English Civil War and the...

in 1649, however, Parliament decided to deliberately destroy, or slight

Slighting

A slighting is the deliberate destruction, partial or complete, of a fortification without opposition. During the English Civil War this was to render it unusable as a fort.-Middle Ages:...

, the defences of castles in key Royalist areas, including the south-west. In the case of Dunster, Thomas's son George Luttrell was able to convince the authorities to destroy only the medieval defensive walls, rather than the entire castle, leaving Dunster damaged from the recent siege but still habitable; the walls were demolished over 12 days in August 1650 by a team of 300 workmen. The only parts of the medieval walls to survive were the Great Gatehouse and the bases of the two towers in the Lower Ward.

George Luttrell died without children, and Dunster Castle passed to his brother Francis, who survived the political turmoil of both the Commonwealth

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the republic which ruled first England, and then Ireland and Scotland from 1649 to 1660. Between 1653–1659 it was known as the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland...

years and the Restoration

Restoration (1660)

The term Restoration in reference to the year 1660 refers to the restoration of Charles II to his realms across the British Empire at that time.-England:...

of Charles II to power in 1660. Francis' heir, another Francis, married a wealthy heiress worth £2,500 a year (£331,000 at 2009 prices) and with this income set about modernising the castle during the 1680s, in particular building a grand staircase in the latest style. Francis was a colonel in the local militia and in 1688 backed William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

's attempt to oust

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

James II

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

; when William landed in Devon, Francis mustered a number of companies of infantry at Dunster on 19 November to support him, which formed the basis for the later Green Howards regiment. During this period the castle still kept an armoury of 43 musket

Musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded, smooth bore long gun, fired from the shoulder. Muskets were designed for use by infantry. A soldier armed with a musket had the designation musketman or musketeer....

s. Francis died heavily in debt in 1690, and his widow Mary moved the contents of the castle to London, where they were destroyed in a fire in 1696.

18th century

James Thornhill

Sir James Thornhill was an English painter of historical subjects, in the Italian baroque tradition.-Life:...

in white Portland stone

Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries consist of beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building stone throughout the British Isles, notably in major...

, on the rear of the mansion at a cost of £1,300 (£178,000 at 2009 prices); few records of this remain, but the interior probably resembled that of the chapel at Wimpole Hall

Wimpole Hall

Wimpole Hall is a country house located within the Parish of Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, England, about 8½ miles southwest of Cambridge. The house, begun in 1640, and its 3,000 acres of parkland and farmland are owned by the National Trust and are regularly open to the public.Wimpole is...

. A safer, if less grand, approach road to the castle was created, called the New Way, and the remains of the Upper Ward on top of the motte were flattened to be used as a bowling green

Bowling green

A bowling green is a finely-laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of lawn for playing the game of lawn bowls.Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep on them...

, complete with an octagonal summer house

Summer house

A summer house or summerhouse has traditionally referred to a building or shelter used for relaxation in warm weather. This would often take the form of a small, roofed building on the grounds of a larger one, but could also be built in a garden or park, often designed to provide cool shady places...

. Dorothy's son, Alexander Luttrell, took over the castle in 1726 but ran up new debts, and the castle was handed over into the control of a receiver

Receivership

In law, receivership is the situation in which an institution or enterprise is being held by a receiver, a person "placed in the custodial responsibility for the property of others, including tangible and intangible assets and rights." The receivership remedy is an equitable remedy that emerged in...

.

Henry Luttrell, who married Alexander's daughter and took the Luttrell name, moved to Dunster in 1747. The couple redesigned and redecorated the castle in a Rococo style, including the extensive use of the recently invented and highly fashionable wallpaper

Wallpaper

Wallpaper is a kind of material used to cover and decorate the interior walls of homes, offices, and other buildings; it is one aspect of interior decoration. It is usually sold in rolls and is put onto a wall using wallpaper paste...

. Henry Luttrell raised the ground height of the Lower Ward between 1764 and 1765 to extend the New Way all around to the front of his mansion, adding additional ornamental towers onto the inside of the Great Gatehouse in the process. A folly

Folly

In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but either suggesting by its appearance some other purpose, or merely so extravagant that it transcends the normal range of garden ornaments or other class of building to which it belongs...

, Conygar Tower

Conygar Tower

The Conygar Tower in Dunster, Somerset, England was built in 1775 and has been designated as a Grade II listed building.It is a circular, 3 storey folly tower built of red sandstone, situated on a hill overlooking the village. It was commissioned by Henry Luttrell and designed by Richard Phelps and...

, was constructed by architect Richard Phelps to improve the view from the castle, and a larger park of 141 hectares (348 acres) was built just to the south of the castle, requiring the eviction of a number of tenant farmers.

19th and 20th centuries

Henry's son, John, inherited the castle in 1780, but when his son, also called John, inherited in 1816 he chose to live in London instead, opening up Dunster Castle to the public. By 1845 the castle appeared to visitors to be past its prime: with only two of John's sisters living there and no horses or hunting dogs left in the castle grounds, the remaining servants had little to do. John's brother Henry inherited in 1857, but he too lived in London rather than at Dunster.George Luttrell inherited the castle in 1867 and began an extensive modernisation, backed by the considerable income from the Dunster estates – in a period of agricultural boom

Boom and bust

A credit boom-bust cycle is an episode characterized by a sustained increase in several economics indicators followed by a sharp and rapid contraction. Commonly the boom is driven by a rapid expansion of credit to the private sector accompanied with rising prices of commodities and stock market index...

in England, the estates were producing £22,000 in revenue a year (£1.49 million at 2010 prices). It was fashionable during the mid-Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

period to remodel existing castles to produce what was felt to be a more consistent Gothic or sometimes Picturesque appearance and George, a keen historian, decided to follow this trend at Dunster; in the process, he also hoped to accommodate the larger household and facilities required for a 19th-century landowner: by 1881, the castle required 15 "living-in" servants alone. He employed Anthony Salvin

Anthony Salvin

Anthony Salvin was an English architect. He gained a reputation as an expert on medieval buildings and applied this expertise to his new buildings and his restorations...

, a noted architect then most famous for his work at Alnwick Castle

Alnwick Castle

Alnwick Castle is a castle and stately home in the town of the same name in the English county of Northumberland. It is the residence of the Duke of Northumberland, built following the Norman conquest, and renovated and remodelled a number of times. It is a Grade I listed building.-History:Alnwick...

, to carry out the work between 1868 and 1872 at a total cost of £25,350 (equivalent to £1.76 million as of 2010).

Salvin aimed to create a castle that would appear to have grown up organically over time, but still appeal to Victorian aesthetic taste. Accordingly, a large, square tower was built on the west side of the castle and another smaller tower on the east, both creating additional space but also making the castle deliberately asymmetrical. The 18th-century chapel at the rear was demolished and replaced with another tower, alongside a modern conservatory

Conservatory (greenhouse)

A conservatory is a room having glass roof and walls, typically attached to a house on only one side, used as a greenhouse or a sunroom...

. A variety of windows in the styles of different historical periods were inserted in the walls, while modern Victorian technology, including gas lighting

Gas lighting

Gas lighting is production of artificial light from combustion of a gaseous fuel, including hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, propane, butane, acetylene, ethylene, or natural gas. Before electricity became sufficiently widespread and economical to allow for general public use, gas was the most...

-supported by a gas

Coal gas

Coal gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made by the destructive distillation of coal containing a variety of calorific gases including hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane and volatile hydrocarbons together with small quantities of non-calorific gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen...

plant

Process Manufacturing

Process manufacturing is the branch of manufacturing that is associated with formulas and manufacturing recipes, and can be contrasted with discrete manufacturing, which is concerned with bills of material and routing....

in the basement-central heating and new kitchens were installed within the castle. The roof of the Great Gatehouse was raised to create a more uniform sequence of battlements, and a large hall for gatherings of the local farmers installed. A new wing of servants' quarters and offices were sunk into the hill, spread over two floors leading away from the main part of the mansion.

Internally, Salvin knocked through existing rooms to create the Outer Hall, a new gallery on the first floor, a billiard room, a new library and a drawing room. Much of the wooden 17th-century panelling in the parlour and the hall had to be stripped out as part of the renovations. As part of his work, Salvin appears to have used a number of rolled wrought-iron beams to span the resulting structural gaps in the building, an advanced use of that technology for the time. The house was refurnished with newly bought 16th and 17th-century artwork, two brass

Brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc; the proportions of zinc and copper can be varied to create a range of brasses with varying properties.In comparison, bronze is principally an alloy of copper and tin...

Italian cannon

Cannon

A cannon is any piece of artillery that uses gunpowder or other usually explosive-based propellents to launch a projectile. Cannon vary in caliber, range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire, and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees,...

s and a stuffed polar bear

Polar Bear

The polar bear is a bear native largely within the Arctic Circle encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the world's largest land carnivore and also the largest bear, together with the omnivorous Kodiak Bear, which is approximately the same size...

.

Alexander Luttrell, who inherited Dunster Castle in 1910, chose to live at East Quantoxhead instead, and it was left empty until his son Geoffrey reoccupied the castle in 1920, redecorating some of the rooms in a contemporary style and building a polo

Polo

Polo is a team sport played on horseback in which the objective is to score goals against an opposing team. Sometimes called, "The Sport of Kings", it was highly popularized by the British. Players score by driving a small white plastic or wooden ball into the opposing team's goal using a...

ground alongside the castle. The castle and the surrounding countryside at this time was very popular with the Luttrells for fox hunting

Fox hunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase, and sometimes killing of a fox, traditionally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds, and a group of followers led by a master of foxhounds, who follow the hounds on foot or on horseback.Fox hunting originated in its current...

and shooting

Shooting

Shooting is the act or process of firing rifles, shotguns or other projectile weapons such as bows or crossbows. Even the firing of artillery, rockets and missiles can be called shooting. A person who specializes in shooting is a marksman...

. During the Second World War the castle was used as a convalescent home for injured naval and American officers between 1943 and 1944.

Alexander died in 1944, and the death duties

Inheritance tax

An inheritance tax or estate tax is a levy paid by a person who inherits money or property or a tax on the estate of a person who has died...

proved crippling to Geoffrey. In 1949 he sold the castle and 3,480 hectares (8,600 acres) of the lands to the Ashdale Property Company, retaining a tenancy of the castle for himself. The Crown Estate

Crown Estate

In the United Kingdom, the Crown Estate is a property portfolio owned by the Crown. Although still belonging to the monarch and inherent with the accession of the throne, it is no longer the private property of the reigning monarch and cannot be sold by him/her, nor do the revenues from it belong...

bought the estate from Ashdale and sold the castle back to Geoffrey in 1954. His son Colonel Walter Luttrell lived away from Dunster, and following the death of his mother – the last Luttrell to live in the property – gave the castle and most of its contents to the National Trust

National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, usually known as the National Trust, is a conservation organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

in 1976.

Today

As of 2011 Dunster Castle is operated by the National Trust as a tourist attractionTourist attraction

A tourist attraction is a place of interest where tourists visit, typically for its inherent or exhibited cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, or amusement opportunities....

. Little remains of the medieval castle except for the Great Gatehouse and the remains of several towers in the Lower Ward; the heart of the modern castle today is the much altered 17th-century manor house. The key features of the castle include the original 13th-century gates and several pieces of art, including a Tudor copy of Hans Eworth

Hans Eworth

Hans Eworth was a Flemish painter active in England in the mid-16th century. Along with other exiled Flemings, he made a career in Tudor London, painting allegorical images as well as portraits of the gentry and nobility. About 40 paintings are now attributed to Eworth, among them portraits of...

's famous allegorical portrait of Sir John Luttrell

John Luttrell (picture)

Sir John Luttrell is an allegorical oil painting of a Tudor soldier.-Details:Sir John Luttrell was an English soldier, diplomat, and courtier under Henry VIII and Edward VI. The Flemish artist Hans Eworth produced a portrait of him in 1550, noted for its use of allegorical images...

, and a sequence of leather tapestries

Tapestry

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven on a vertical loom, however it can also be woven on a floor loom as well. It is composed of two sets of interlaced threads, those running parallel to the length and those parallel to the width ; the warp threads are set up under tension on a...

showing scenes from the story of Antony and Cleopatra

Antony and Cleopatra

Antony and Cleopatra is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written sometime between 1603 and 1607. It was first printed in the First Folio of 1623. The plot is based on Thomas North's translation of Plutarch's Lives and follows the relationship between Cleopatra and Mark Antony...

. The gardens surrounding the castle cover approximately 6 hectares (14.8 acre) and include the National Plant Collection

NCCPG National Plant Collection

The NCCPG National Plant Collection scheme is the main conservation vehicle whereby the National Council for the Conservation of Plants and Gardens can accomplish its mission: to conserve, grow, propagate, document and make available the resource of garden plants that exists in the United...

of Strawberry Trees; the wider parkland beyond totals 277 hectares (684.5 acre). Just to the south of the castle is the restored 18th-century castle watermill

Dunster Working Watermill

Dunster Working Watermill is a restored 18th century watermill, situated on the River Avill, in the grounds of Dunster Castle in Dunster, Somerset, England....

. In 2010 the castle received 128,242 visitors.

Dunster Castle has been designated by English Heritage

English Heritage

English Heritage . is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport...

as a Grade I listed building and Scheduled Ancient Monument

Scheduled Ancient Monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a 'nationally important' archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorized change. The various pieces of legislation used for legally protecting heritage assets from damage and destruction are grouped under the term...

. The castle has required continuing maintenance work, in particular to its roof, itself an important historical feature. Efforts have been made to gradually redecorate the castle in a period style, using reproductions of original wallpapers and materials. The National Trust installed solar panels behind the battlements on the roof in 2008 to provide electricity and make the premises more environmentally friendly. This was the first time the National Trust have taken this approach to a Grade I listed building, and it is expected to save 1,714 kg (3,778 lb) of carbon

Carbon

Carbon is the chemical element with symbol C and atomic number 6. As a member of group 14 on the periodic table, it is nonmetallic and tetravalent—making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds...

a year.

See also

- List of Grade I listed buildings in West Somerset

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England