Donald Henderson

Encyclopedia

Donald Ainslie Henderson, known as D.A. Henderson, (born September 7, 1928) is an American physician

and epidemiologist, who headed the international effort during the 1960s to eradicate smallpox

. , he is a Distinguished Scholar at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's

Center for Biosecurity and a professor of public health and medicine at the University of Pittsburgh

. He is also a Johns Hopkins University Distinguished Service Professor and Dean Emeritus of the School of Public Health, with a joint appointment in the Department of Epidemiology.

in the United States. He graduated from Oberlin College

in 1950 and received his M.D.

from the University of Rochester School of Medicine

in 1954. He served both an internship (1954–1955) and a residency (1957–1959) in medicine at the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, New York

. He earned an M.P.H. degree in 1960 from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health (now the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

).

Between his internship and residency (1955–1957) and again from 1960–1966, he worked in the Epidemic Intelligence Service

of the Communicable Disease Center

(CDC; now the National Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), where he created a Smallpox Surveillance Unit to deal with imports of the disease into the USA.

to head the World Health Organization

's Global Smallpox Eradication Campaign. Smallpox was at the time endemic

in Brazil, Africa and South Asia.

In 1972 Henderson helped suppress an outbreak of smallpox in Yugoslavia

, the last epidemic of smallpox in Europe. In 1974 he was stationed in India

during one of the largest epidemics in the 20th century and was instrumental in initiating the global program of immunization

. This program has vaccinated 80 percent of the world's children against six major diseases and is striving to eradicate poliomyelitis

.

The smallpox eradication campaign came to a successful conclusion in 1977 when the last case was reported in Somalia

. It thus became the first infectious disease to be wiped out.

of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. His government service was first as associate director, Office of Science and Technology Policy

, Executive Office of the President

(1991–1993), and later as deputy assistant secretary and senior science advisor in the Department of Health and Human Services (HSS). He is also currently a senior advisor to the federal government and the HHS on civilian biodefense

issues. He rejoined the faculty of Johns Hopkins in June 1995 after five years of federal government service.

In October 2001, Tommy G. Thompson

, Secretary of Health and Human Services, named Henderson chair

of a new national advisory council on public health preparedness which is charged with improving the national public health infrastructure to better counter bioterrorist

attacks. As the principal science advisor for public health preparedness in HHS and chair of the Secretary's Council on Public Health Preparedness, Henderson is in charge of coordinating department-wide response to public health emergencies. He was also the founding director in 1998 of the Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Strategies, which he has directed for the past four years, and has numerous publications to his credit.http://commprojects.jhsph.edu/faculty/detail.cfm?id=122&Lastname=Henderson&Firstname=Donald

The Donald A. Henderson Collection at Johns Hopkins spans his entire career there, including newspaper articles, honors, biographical material, lecture notes, speeches, and correspondence as well as awards such as the Japan Prize and the Public Welfare Medal. Presently, he is a Professor and Resident Scholar at the Center for Biosecurity of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

, which has created a professorship honoring him as of September 26, 2004.

Physician

A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

and epidemiologist, who headed the international effort during the 1960s to eradicate smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

. , he is a Distinguished Scholar at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center is an $9 billion integrated global nonprofit health enterprise that has 54,000 employees, 20 hospitals, 4,200 licensed beds, 400 outpatient sites and doctors’ offices, a 1.5 million-member health insurance division, as well as commercial and...

Center for Biosecurity and a professor of public health and medicine at the University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh, commonly referred to as Pitt, is a state-related research university located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded as Pittsburgh Academy in 1787 on what was then the American frontier, Pitt is one of the oldest continuously chartered institutions of...

. He is also a Johns Hopkins University Distinguished Service Professor and Dean Emeritus of the School of Public Health, with a joint appointment in the Department of Epidemiology.

Early life

Henderson was born in Lakewood, OhioLakewood, Ohio

Lakewood is a city in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. It is part of the Greater Cleveland Metropolitan Area, and borders the city of Cleveland. The population was 52,131 at the 2010 making it the third largest city in Cuyahoga County, behind Cleveland and Parma .Lakewood, one of Cleveland's...

in the United States. He graduated from Oberlin College

Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college in Oberlin, Ohio, noteworthy for having been the first American institution of higher learning to regularly admit female and black students. Connected to the college is the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the oldest continuously operating...

in 1950 and received his M.D.

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

from the University of Rochester School of Medicine

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private, nonsectarian, research university in Rochester, New York, United States. The university grants undergraduate and graduate degrees, including doctoral and professional degrees. The university has six schools and various interdisciplinary programs.The...

in 1954. He served both an internship (1954–1955) and a residency (1957–1959) in medicine at the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

. He earned an M.P.H. degree in 1960 from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health (now the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is part of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, United States...

).

Between his internship and residency (1955–1957) and again from 1960–1966, he worked in the Epidemic Intelligence Service

Epidemic Intelligence Service

The Epidemic Intelligence Service is a program of the United States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Established in 1951, due to biological warfare concerns arising from the Korean War, it has become a hands-on two-year postgraduate training program in epidemiology, with a focus on...

of the Communicable Disease Center

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are a United States federal agency under the Department of Health and Human Services headquartered in Druid Hills, unincorporated DeKalb County, Georgia, in Greater Atlanta...

(CDC; now the National Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), where he created a Smallpox Surveillance Unit to deal with imports of the disease into the USA.

Eradication of smallpox

In 1966 Henderson moved to GenevaGeneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

to head the World Health Organization

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations that acts as a coordinating authority on international public health. Established on 7 April 1948, with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, the agency inherited the mandate and resources of its predecessor, the Health...

's Global Smallpox Eradication Campaign. Smallpox was at the time endemic

Endemic (epidemiology)

In epidemiology, an infection is said to be endemic in a population when that infection is maintained in the population without the need for external inputs. For example, chickenpox is endemic in the UK, but malaria is not...

in Brazil, Africa and South Asia.

In 1972 Henderson helped suppress an outbreak of smallpox in Yugoslavia

1972 outbreak of smallpox in Yugoslavia

The 1972 outbreak of smallpox in Yugoslavia was the last major outbreak of smallpox in Europe. It was centred in Kosovo and Belgrade, Serbia . A Muslim pilgrim had contracted the smallpox virus in the Middle East. Upon returning to his home in Kosovo, he started the epidemic in which 175 people...

, the last epidemic of smallpox in Europe. In 1974 he was stationed in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

during one of the largest epidemics in the 20th century and was instrumental in initiating the global program of immunization

Immunization

Immunization, or immunisation, is the process by which an individual's immune system becomes fortified against an agent ....

. This program has vaccinated 80 percent of the world's children against six major diseases and is striving to eradicate poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, often called polio or infantile paralysis, is an acute viral infectious disease spread from person to person, primarily via the fecal-oral route...

.

The smallpox eradication campaign came to a successful conclusion in 1977 when the last case was reported in Somalia

Somalia

Somalia , officially the Somali Republic and formerly known as the Somali Democratic Republic under Socialist rule, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. Since the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in 1991 there has been no central government control over most of the country's territory...

. It thus became the first infectious disease to be wiped out.

Later work

From 1977 through August 1990, Henderson was deanDean (education)

In academic administration, a dean is a person with significant authority over a specific academic unit, or over a specific area of concern, or both...

of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. His government service was first as associate director, Office of Science and Technology Policy

Office of Science and Technology Policy

The Office of Science and Technology Policy is an office in the Executive Office of the President , established by Congress on May 11, 1976, with a broad mandate to advise the President on the effects of science and technology on domestic and international affairs.The director of this office is...

, Executive Office of the President

Executive Office of the President of the United States

The Executive Office of the President consists of the immediate staff of the President of the United States, as well as multiple levels of support staff reporting to the President. The EOP is headed by the White House Chief of Staff, currently William M. Daley...

(1991–1993), and later as deputy assistant secretary and senior science advisor in the Department of Health and Human Services (HSS). He is also currently a senior advisor to the federal government and the HHS on civilian biodefense

Biodefense

Biodefense refers to short term, local, usually military measures to restore biosecurity to a given group of persons in a given area who are, or may be, subject to biological warfare— in the civilian terminology, it is a very robust biohazard response. It is technically possible to apply...

issues. He rejoined the faculty of Johns Hopkins in June 1995 after five years of federal government service.

In October 2001, Tommy G. Thompson

Tommy Thompson

Thomas George "Tommy" Thompson , a United States Republican politician, was the 42nd Governor of Wisconsin, after which he served as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services. Thompson was a candidate for the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election, but dropped out early after a poor performance in polls...

, Secretary of Health and Human Services, named Henderson chair

Chair (official)

The chairman is the highest officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office is typically elected or appointed by the members of the group. The chairman presides over meetings of the assembled group and conducts its business in an...

of a new national advisory council on public health preparedness which is charged with improving the national public health infrastructure to better counter bioterrorist

Bioterrorism

Bioterrorism is terrorism involving the intentional release or dissemination of biological agents. These agents are bacteria, viruses, or toxins, and may be in a naturally occurring or a human-modified form. For the use of this method in warfare, see biological warfare.-Definition:According to the...

attacks. As the principal science advisor for public health preparedness in HHS and chair of the Secretary's Council on Public Health Preparedness, Henderson is in charge of coordinating department-wide response to public health emergencies. He was also the founding director in 1998 of the Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Strategies, which he has directed for the past four years, and has numerous publications to his credit.http://commprojects.jhsph.edu/faculty/detail.cfm?id=122&Lastname=Henderson&Firstname=Donald

The Donald A. Henderson Collection at Johns Hopkins spans his entire career there, including newspaper articles, honors, biographical material, lecture notes, speeches, and correspondence as well as awards such as the Japan Prize and the Public Welfare Medal. Presently, he is a Professor and Resident Scholar at the Center for Biosecurity of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center is an $9 billion integrated global nonprofit health enterprise that has 54,000 employees, 20 hospitals, 4,200 licensed beds, 400 outpatient sites and doctors’ offices, a 1.5 million-member health insurance division, as well as commercial and...

, which has created a professorship honoring him as of September 26, 2004.

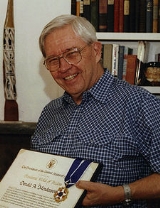

Honors and awards

- 1976 - Ernst Jung PrizeErnst Jung PrizeThe Ernst Jung Prize is a prize awarded annually for excellence in biomedical sciences. The Ernst Jung Foundation, funded by Hamburg merchant Ernst Jung in 1967 grants the Ernst Jung Prize in Medicine, now € 300,000, since 1976 and the lifetime achievement Ernst Jung Gold Medal for Medicine since...

- 1978 - Public Welfare MedalPublic Welfare MedalThe Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the Academy...

, the National Academy of SciencesUnited States National Academy of SciencesThe National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

' highest award. - 1986 - The National Medal of ScienceNational Medal of ScienceThe National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social sciences, biology, chemistry, engineering, mathematics and...

in Biology, presented by the President of the United States. - 1988 - The Japan PrizeJapan Prizeis awarded to people from all parts of the world whose "original and outstanding achievements in science and technology are recognized as having advanced the frontiers of knowledge and served the cause of peace and prosperity for mankind."- Explanation :...

, shared with Isao Arita and Frank FennerFrank FennerFrank John Fenner, AC, CMG, MBE, FRS, FAA was an Australian scientist with a distinguished career in the field of virology...

. - 1994 - Albert B. Sabin Gold MedalAlbert B. Sabin Gold MedalThe Albert B. Sabin Gold Medal is awarded annually by the Sabin Vaccine Institute in recognition of work in the field of vaccinology or a complementary field. It is in commemoration of the pioneering work of Albert B. Sabin.-List of previous recipients:...

- 1995 - John Stearns Medal for Distinguished Contributions in Medicine from the New York Academy of MedicineNew York Academy of MedicineThe New York Academy of Medicine was founded in 1847 by a group of leading New York City metropolitan area physicians as a voice for the medical profession in medical practice and public health reform...

. - 1996 - The Edward Jenner Medal, received from the Royal Society of MedicineRoyal Society of MedicineThe Royal Society of Medicine is a British charitable organisation whose main purpose is as a provider of medical education, running over 350 meetings and conferences each year.- History and overview :...

. - 2000 - He was elected an Honorary Fellow of the New York Academy of MedicineNew York Academy of MedicineThe New York Academy of Medicine was founded in 1847 by a group of leading New York City metropolitan area physicians as a voice for the medical profession in medical practice and public health reform...

, one of just 12 Honorary Fellows among the Academy's 2,500 members. - 2002 - The Presidential Medal of FreedomPresidential Medal of FreedomThe Presidential Medal of Freedom is an award bestowed by the President of the United States and is—along with thecomparable Congressional Gold Medal bestowed by an act of U.S. Congress—the highest civilian award in the United States...

from President George W. Bush for a lifetime of work in the service of his country and humanity. - A total of 16 universities have conferred honorary degrees and 14 countries have honored him with awards and decorations, as well as WHO and the Pan American Health OrganizationPan American Health OrganizationThe Pan American Health Organization is an international public health agency with over 100 years of experience working to improve health and living standards of the people of the Americas...

.

Selected publications

- Smallpox: The Death of a Disease by D.A. Henderson