.gif)

David Lewis (politician)

Encyclopedia

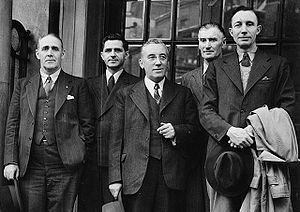

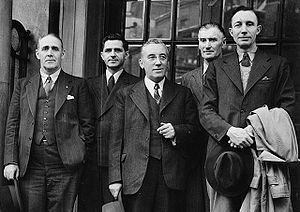

David Lewis, CC

(born David Losz; June 23, or October 1909 – May 23, 1981) was a Russian-born Canadian labour lawyer and social democratic

politician. He was national secretary of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

(CCF) from 1936 to 1950, and one of the key architects of the New Democratic Party

(NDP) in 1961. In 1962, he was elected as the Member of Parliament

(MP), in the Canadian House of Commons

, for the York South

electoral district. While an MP, he was elected the NDP's national leader, where he served from 1971 to 1975. After his defeat in the 1974 federal election, he stepped down as leader and retired from politics. He spent his last years as a university professor and travel correspondent for the Toronto Star

. In retirement, he was named to the Order of Canada

for his political service. After a lengthy battle with cancer, he died in Ottawa

in 1981.

Lewis' politics were heavily influenced by the Jewish Labour Bund, which contributed to his support of parliamentary democracy. He was an avowed anti-communist, and while a Rhodes Scholar

prevented communist domination of the Oxford University Labour Club

. In Canada, he played a major role in removing communist influence from the labour movement

.

In the CCF, he took the role of disciplinarian and dealt with internal organizational problems. He helped draft the Winnipeg Declaration

, which moderated the CCF's economic policies to include acceptance of capitalism, albeit subject to stringent government regulation. As the United Steelworkers of America (USW)'s legal counsel in Canada, he helped them take over the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (Mine-Mill). His involvement with the USW also led to a central role in the creation of the Canadian Labour Congress

in 1956.

The Lewis family has been active in socialist politics since the turn of the twentieth century, starting with David Lewis' father's involvement in the Bund in Russia, continuing with David, and followed by his eldest son, Stephen Lewis

, who led the Ontario NDP from 1970 until 1978. When David was elected the NDP's national leader in 1971, he and Stephen became one of the first father-and-son-teams to simultaneously head Canadian political parties.

he lived in from 1909 until 1921. Svisloch was located in the Pale of Settlement

, the western-most region of the Russian Empire

, in what is now Belarus

. After World War I it became a Polish border town, occasionally occupied by the Soviet Union

during the Polish-Soviet War

of the early 1920s. Jewish people were in the majority, numbering 3,500 out of Svisloch's 4,500 residents. Unlike many of the other shtetls in the Pale, it had an industrial economy based on tanning

. Its semi-urban industrial population was receptive to social democratic politics and the labour movement

, as embodied by the Jewish Labour Bund.

Moishe (or Moshe) Losz was Svisloch's Bund Chairman. The Bund was an outlawed socialist party that called for overthrowing the Tsar

, equality for all, and national rights for the Jewish community; it functioned as both political party and labour movement. Lewis spent his formative years immersed in its culture and philosophy. The Bund's membership, although mostly ethnically Jewish, was secular humanist in practice.

Moishe and David were influenced by the Bund's political pragmatism, embodied in its maxim that "It is better to go along with the masses in a not totally correct direction than to separate oneself from them and remain a purist." David would bring this philosophy to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and New Democratic Party (NDP); in clashes between the parties' "ideological missionaries and the power pragmatists when internal debates raged about policy or action", he was in the latter camp.

When the Russian Civil War

and the Polish-Soviet War

were at their fiercest, in the summer of 1920, Poland invaded, and the Red Russian Bolshevik

army counter-attacked. The Bolsheviks reached the Svisloch border in July 1920. Moishe Losz openly opposed the Bolsheviks and would later be jailed by them for his opposition. When the Polish army recaptured Svisloch on August 25, 1920, they executed five Jewish citizens as "spies". Unsafe under either regime and with his family's future prospects bleak, Moishe left for Canada in May 1921, to work in his brother-in-law's Montreal

clothing factory. By August, he saved enough money to send for his family, including David and his siblings, Charlie and Doris.

David Lewis was a secular Jew, as was Moishe. However, his maternal grandfather, Usher Lazarovitch, was religious and, in the brief period between May and August 1921 before David emigrated, gave his grandson the only real religious training he would ever receive. David did not actively take part in a religious service again until his granddaughter Ilna's Bat Mitzvah in the late 1970s. In practice, the Lewis family, including David, his wife Sophie, and their children Janet, Stephen, and Michael, were atheists.

, Nova Scotia

. They then went by rail to Montreal to meet Moishe Lewis. David Lewis was a native Yiddish speaker and understood very little English. He learned it by buying a copy of Charles Dickens

' novel The Old Curiosity Shop

and a Yiddish-English dictionary. A Welsh

teacher at Fairmont Public School, where Lewis was a student, helped him learn English but also passed on his Welsh accent.

Lewis entered Baron Byng High School

in September 1924. He soon became friends with A.M. (Abe) Klein, who was to become one of Canada's leading poets. He also met Irving Layton

, another future major poet, to whom he acted as political mentor. Baron Byng High School was predominately Jewish because it was in the heart of Montreal's non-affluent Jewish community, and was ghetto-like because Jews were forbidden from attending many high schools.

Besides poets, at high school Lewis met Sophie Carson, who eventually became his wife. Klein, their mutual friend, introduced them. Carson was a first generation Jewish-Canadian from a religious family. Her father did not approve of Lewis, because he was a recent immigrant to Canada, and in Carson's father's opinion had little to no possibility of success.

After high school, Lewis spent five years at McGill University

in Montreal: four in arts, and one in law. While there, he helped found the Montreal branch of the Young People's Socialist League

. He gave lectures sponsored by this anti-communist socialist club, and was its nominal leader. One of his favourite professors was Canadian humorist, and noted Conservative party proponent, Stephen Leacock

, whom Lewis liked more for his personality than for his discipline, economics.

In his third year, Lewis founded The McGilliad campus magazine. It published many of his anti-communist views, though the December 1930 issue included an article he wrote expressing his approval of the Russian Revolution and calling for a greater understanding of the Soviet Union; throughout his career, he would attack communism, but would always have a sympathy for the 1917 revolutionaries. Also at McGill, Lewis met and worked with prominent Canadian socialists like F.R. Scott, Eugene Forsey

, J. King Gordon

, and Frank Underhill

. He would work with all of them again in the 1940s and 50s in the CCF.

during his first year at law school. The interviews for the Quebec representative were conducted in Montreal. The examining board included the then-president of the Canadian Pacific Railway

(CPR), Sir Edward Beatty

. In response to a question about what he would do if he became prime minister, Lewis stated that he would nationalize the CPR. Despite this answer and his socialist views in general, his responses to the board's cross-examination satisfied them that he was not a communist, and they awarded him the scholarship.

, Oxford, in 1932, he immediately took a leadership role in the university's socialist-labour circles. Michael Foot

, the future leader of the British Labour Party, mentioned in an interview that Lewis was,

When Lewis came to Oxford, the Labour Club

was a tame organization adhering to Christian activism

, or genteel socialist theories like those expressed by R.H. Tawney in his book The Acquisitive Society. Lewis' modified Bundist

interpretation of Marxism, which Smith labels "Parliamentary Marxism", ignited renewed interest in the club after the disappointment of Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government.

The Oxford newspaper Isis

noted Lewis' leadership ability at this early stage in his career. In its February 7, 1934, issue, while Lewis was president, they wrote of the club: "The energy of these University Socialists is almost unbelievable. If the Socialist movement as a whole is anything like as active as they are, then a socialist victory at the next election is inevitable."

In February 1934, British fascist William Joyce

(Lord Haw Haw) visited Oxford. Lewis and future Ontario CCF

leader Ted Jolliffe

organized a noisy protest by planting Labour Club members in the dance hall where Joyce was speaking and having groups of two and three of them leave at a time, making much noise on the creaking wooden floors. They were successful in drowning out Joyce, and he did not complete his speech. Afterwards, a street fight erupted between Joyce's Blackshirt supporters and members of the Labour Club, including Lewis.

Lewis prevented the communists from making inroads at Oxford. Ted Jolliffe stated "there was a difference between his speeches at the Union and his speeches at the Labour Club. His speeches at the Union had more humour in them; the atmosphere was entirely different. But his speeches at the Labour Club were deadly serious ... His influence at the Labour Club, more than anyone else's, I think, explains the failure of the Communists to make headway there. There were so many naive people around who could have been taken in." He increased the Labour Club's membership by three quarters by the time he left.

In accordance with Bundism, Lewis rejected violent revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat

. The Bund insisted that the revolution should be through democratic means, as Marx

had judged possible in the late 1860s, and that democracy should prevail afterwards. Influenced by Fabianism, Lewis became an incrementalist in his approach to replacing non-socialist governments. As Lewis biographer Cameron Smith points out:

Lewis was a prominent figure in the British Labour Party

, which, in emphasizing parliamentary action and organizational prowess, took an approach similar to the Bund's. Upon his 1935 graduation, the party offered him a candidacy in a safe seat

in the British House of Commons

. This left Lewis with a difficult decision: whether to stay in England or go home to Canada. If he had stayed in England, he likely would have been a partner in a prominent London law firm associated with Stafford Cripps

and become a cabinet minister the next time Labour formed a government. Cripps, then a prominent barrister and Labour Party official, was grooming Lewis to be Prime Minister

. Lewis' other choice was to return to Montreal and help build the fledgling Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), with no guarantee of success. A personal note from J. S. Woodsworth

, dated June 19, 1935, asked Lewis to take this latter option; in the end, he did.

, probably the most prestigious and important debating club in the English-speaking world. His first debate, in January 1933, was on the resolution "That the British Empire

is a menace to International good will"; Lewis was one of the participants for the "Aye" side. They lost.

The February 9, 1933, debate brought Lewis some level of early prominence. The resolution was "That this House will under no circumstances fight for its King or Country

" and was so controversial that it was news around the British Empire and beyond. Lewis again spoke for the "Aye" side. They won overwhelmingly and caused a newspaper uproar throughout the Empire. The Times of London entered the fray by pooh-poohing those who took the Union and their motion seriously.

Lewis became a member of the Union's Library Committee on March 9, 1933, and its treasurer in March 1934. After two failed attempts, he was narrowly elected president in late November 1934. He was president during the Hilary term

, from the beginning of January until the end of April 1935. The Isis commented that "... David Lewis ... will be, beyond question, the least Oxonian person ever to the lead the Society. In appearance, background, and intellectual outlook he is a grim antithesis to all the suave, slightly delicate young men who for generations have sat on the Union rostrum ..."

In 1935 David Lewis became the National Secretary of the CCF. As Smith puts it:

Most of the founders of the CCF – including Woodsworth, Tommy Douglas

, M. J. Coldwell

, and Stanley Knowles

, – were informed by the Social Gospel

, to which Lewis, with his Marxist socialism balanced by the Bund's democratic principles, felt an affinity. Both the Bund and the Social Gospel were focused on the material present rather than the afterlife. Both called on people to change their environment for the better rather than hoping that God might do it for them. Social justice, the brotherhood of man, and moral self-improvement were common to both.

It became obvious after the October 1937 Ontario election

that the CCF needed an image change; it was seen by the electorate as too far left. F.R. Scott pointed this out to Lewis in a letter, recommended moderating some of the party's policies, and advised that "... in the political arena we must find our friends among the near right."

In August 1938, Lewis quit his job at the Ottawa law firm of Smart and Biggar to work full-time as the CCF National Secretary. His starting salary was $1,200 per year, a low sum of money, even at that time, for job with so much responsibility.

's more radical language, which seemed to scare off moderate voters. The offending language included "No CCF government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning ..." Lewis, federal leader M.J. Coldwell, and Clarie Gillis

would spend the next 19 years trying to modify this declaration, finally succeeding with the 1956 Winnipeg Declaration

.

At the 1944 CCF convention, Lewis won a concession "that even large business could have a place in the party – if they behave." Rather than opposing all private enterprise, Lewis was concerned with preventing monopoly capitalism. He passed a resolution reading "The socialization of large-scale enterprise, however, does not mean taking over every private business. Where private business shows no signs of becoming a monopoly, operates efficiently under decent working conditions, and does not operate to the detriment of the Canadian people, it will be given every opportunity to function, to provide a fair rate of return and to make its contribution to the nation's wealth." This resolution allowed for a mixed-economy that left most jobs in the private sphere.

Lewis did not share the desire of some members to keep the CCF "ideologically pure", and adhered to the Bundist belief that "it was better to go along with the masses in a not totally correct direction than to separate oneself from them and remain 'purist'." However, the CCF was as much a movement as it was a political party, and its own members frequently undermined it with radical proclamations. Lewis criticized the British Columbia CCF for such comments, saying "... what we say and do must be measured by the effect which it will have on our purpose of mobilizing people for action. If what we say and do will blunt or harm our purpose ... then we are saying and doing a false thing even if, in the abstract, it is true ... When, in heaven's name are we going to learn that working-class politics and the struggle for power are not a Sunday-school class where purity of godliness and the infallibility of the Bible must be held up without fear of consequences."

Lewis did not share the desire of some members to keep the CCF "ideologically pure", and adhered to the Bundist belief that "it was better to go along with the masses in a not totally correct direction than to separate oneself from them and remain 'purist'." However, the CCF was as much a movement as it was a political party, and its own members frequently undermined it with radical proclamations. Lewis criticized the British Columbia CCF for such comments, saying "... what we say and do must be measured by the effect which it will have on our purpose of mobilizing people for action. If what we say and do will blunt or harm our purpose ... then we are saying and doing a false thing even if, in the abstract, it is true ... When, in heaven's name are we going to learn that working-class politics and the struggle for power are not a Sunday-school class where purity of godliness and the infallibility of the Bible must be held up without fear of consequences."

David Lewis was the party's "heavy", which did not help his popularity among CCF members, but after witnessing what he considered to be the European left's self-destruction in the 1930s, he was quick to end self-immolating tactics or policies. He would tolerate some criticism of the party by its members, but when he believed that it rose to self-mutilation, he suppressed it ruthlessly. This was most apparent when Lewis attacked and discredited Frank Underhill and his handling of Woodsworth House.Woodsworth House was both a building and political think-tank, the home of the Ontario CCF (the party that was involved in the Province of Ontario's politics). It was created by a financial foundation that was independent of the Ontario CCF. It took its name from the first CCF leader. The house was inaugurated in January 1947, but ran into financial difficulties in the late 1940s, due to the educational programme that Underhill was responsible for. He allowed the expenses for publishing papers and other materials to exceed the budget, and his only solution was to sell Woodsworth House to pay the debt off. Also of note, Frank Underhill was one of the founders of the League of Social Reconstruction, and one of the people who drafted the CCF's Regina Manifesto in 1933. He was a prominent University of Toronto professor and until the Woodsworth House event, held in the same esteem as Lewis, by party members, Early in Lewis' career, Underhill was one of his mentors; this did not matter when Woodsworth House was stricken with financial difficulties in the late 1940s. Lewis was quick to blame and then discharged Underhill and the rest of the Woodsworth executive of their responsibilities. It was an unfortunate event that cost the CCF in the academic and intelligentsia world. To sum up Lewis' reign, discipline and solidarity were paramount. There had to be limits to discussion and tolerance of dissenting views.

had proven itself during wartime with the King government's imposition of wage and price controls through the Wartime Prices and Trade Board. Lewis and Scott further argued that its wartime success could translate to peacetime, and that Canada should adopt a mixed economy

. They also called for public ownership of key economic sectors, and for the burden to be placed on private companies to demonstrate that they could manage an industry more effectively in the private sector than the government could in the public sector. The book also outlined the history of the CCF up to that time and explained the party's decision-making process. By Canadian standards, the book was popular, and sold over 25,000 copies in its first year of publication.Make This Your Canada was re-printed in 2001, by the Hybrid Publishers Co-operative Ltd. – in time for the pivotal federal New Democratic Party convention in Winnipeg.

in York West

. He placed a distant third, receiving 8,330 fewer votes than the second place Liberal candidate, Chris J. Bennett. Despite his poor showing in his first election, the party asked Lewis to run in the 1943 by-election in the Montreal, Quebec

, federal riding of Cartier

, made vacant by the death of Peter Bercovitch

. Lewis' opponents included Fred Rose

of the communist Labour–Progressive Party. It was a vicious campaign, immortalized by A.M. Klein in an uncompleted novel called Come the Revolution. The novel was broadcast in the 1980s on Lister Sinclair'sSinclair co-wrote Ontario CCF leader Ted Jolliffe's "Gestapo" speech during the 1945 Ontario general election, that lead to the appointment of the LeBel Royal Commission

. Ideas

programme on CBC Radio One

. If the Communist rhetoric could be believed, "Lewis was a Fascist done up in brown."

Rose won and became the only (as of 2011) Communist to sit in the House of Commons. Lewis placed fourth. The sizable Jewish vote mostly went to Rose. The leftist "common front" punished Lewis by supporting Rose, who was seen to be of the community; Lewis lived in Ottawa at the time. It took Lewis many years to recover from this campaign, and its reverberation coloured Lewis' decision on where to run.

|-

|Fred Rose

||align=right|5,789||align=right|30.42

|-

|Paul Masse ||align=right|5,639||align=right|29.63

|-

|Lazarus Phillips

||align=right|4,180||align=right|21.97

|-

|David Lewis ||align=right|3,313||align=right|17.41

|-

|Moses Miller||align=right|109||align=right|0.57

and the Ontario elections of 1945

were possibly the most crucial to Canada in the 20th century. They took place at the beginning of the welfare state

, and the elections would set the course of political thought to the end of the century and beyond. The year was a disaster for the CCF, both nationally and in Ontario. It never fully recovered, and in 1961 would dissolve and become the New Democratic Party. As NDP strategist and historian Gerald Caplan

put it: "June 4, and June 11, 1945, proved to be black days in CCF annals: socialism was effectively removed from the Canadian political agenda."

The anti-socialist crusade by the Ontario Conservative Party

, mostly credited to the Ontario Provincial Police

(OPP) special investigative branch's agent D-208 (Captain William J. Osborne-Dempster) and the Conservative propagandists Gladstone Murray and Montague A. Sanderson, diminished the CCF's initially favourable position: the September 1943 Gallup poll showed the CCF leading nationally with 29 percent support, with the Liberals and Conservatives tied for second place at 28 percent. By April 1945, the CCF was down to 20 percent nationally, and on election day it received only 16 percent.

Another factor in the CCF's defeat was the unofficial coalition between the Liberal Party of Canada

and the communist Labour-Progressive Party. It guaranteed a split in the left-of-centre vote.

Lewis ran in Hamilton West instead of the CCF-friendly Winnipeg North

riding that had elected CCF and Labour Party candidates since the 1920s and had a substantial Jewish population. Historians and activists disagree on Lewis' reasons for doing so, but Caplan suggests that the shock of the Cartier election probably made him reluctant to fight another intense campaign against a Jewish Communist candidate. Whatever his reasons, he was soundly defeated. In the 1949 federal election

, Lewis ran again in the Hamilton

area, in the riding of Wentworth

. He lost again, placing a relatively distant third.

The Canadian Congress of Labour

(CCL) supported the CCF, but the Trades and Labour Congress

(TLC) refused to officially endorse them. This lack of unity between the two main Canadian umbrella labour organizations hurt the CCF, and was part of the Liberal–Communist alliance: TLC president Percey Berough was a Liberal, and vice-president Pat Sullivan was a Communist.

In the Ontario provincial election, the communists urged trade union members to vote for the right-wing Conservative George Drew rather than the CCF.

Lewis and Charles Millard

, of the Canadian Congress of Labour, decided to purge organized labour's decision-making bodies of communists. Their first target was the Sudbury, Ontario, CCF riding association and its affiliated International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (Mine-Mill) Local 598. However, Local 598 was not under Communist control: out of 11,000 dues-paying members, fewer than 100 were communists. Over the next twenty years, a fierce and ultimately successful battle was waged by Millard's United Steel Workers of America (USW) to take over Local 598.

The attacks on the Sudbury CCF were even more costly, at least in terms of voter support. Sudbury's Bob Carlin

was one of the few CCF Members of Provincial Parliament (MPPs) to survive the Drew government's 1945 landslide victory. Carlin had been part of Ted Jolliffe's team that had orchestrated the CCF's 1943 breakthrough, but was first and foremost a union man. He was a long-time labour organizer, going back to 1916 and the predecessor to the Mine-MIll: the Western Federation of Miners

. Carlin was loyal to his union, in whose service he had spent ten years, and to the men and woman who helped build it, regardless of their political affiliation; this made him unpopular with the CCF establishment in both Toronto and Ottawa.

Millard, Jolliffe, and Lewis did not directly accuse Carlin of being a communist. Instead, they attacked him for not dealing with communists in Local 598, which was built by both communists and CCFers (with the latter firmly in control of the executive). Lewis and Jolliffe made the case to expel him from the Ontario CCF caucus at a Toronto special meeting of the CCF executive and the legislative caucus on April 13, 1948. In essence, Carlin became a casualty of Steel's plans to raid Mine-Mill. The CCF lost the seat in the 1948 Ontario election

, placing fourth. The Conservatives won the seat and Carlin, as an independent, finished a close second. It was not until the CCF became the New Democratic Party (NDP) and the Mine-Mill versus USW war was over, in 1967, that another social democrat – Elie Martel

in Sudbury East

– was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario from the city.

Lewis and Millard's crusade to limit communist influence received an unexpected boost from the Soviet Union

, in Nikita Khrushchev

's 1956 denunciation of Stalinism

. In his "Secret Speech", On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

, delivered to a closed session of the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

, Khrushchev denounced Stalin for his cult of personality, and his regime for "violation of Leninist norms of legality". When the excesses of Stalin

's regime were exposed, it caused a split in the communist movement in Canada and permanently weakened it. By the end of 1956, the LPP's influence in the trade union movement and politics was spent.

to practise law in partnership with Ted Jolliffe. He became the chief legal advisor to the USW's Canadian division, and assisted them in their organizing efforts and battles with the Mine-Mill union. Lewis focused on his law practice for the next five years. In his first year, he paid more in income tax than he had earned annually as CCF National Secretary.

He bought his first house, in the Bathurst Street – St. Clair Avenue

West area of Toronto, during this period. After his father Moishe died in 1951, his mother Rose moved into the 95 Burnside Drive Lewis home from Montreal. This is the home where his son Stephen Lewis would spend his teenage years, and the other three children would grow up.

. He, along with Lorne Ingle, the person that replaced him as national secretary in 1950, became the main drafters of the 1956 Winnipeg Declaration, which replaced the Regina Manifesto. The lead-up to the August 1956 CCF convention had Lewis working full-time in his labour practice, including work on the merger of the Canadian Congress of Labour and the Trades and Labour Congress to form the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), and putting in long hours organizing the committee that wrote the Declaration. He collapsed in his office in May 1956; after administering several tests for a possible cardiac condition, the doctors concluded that Lewis collapsed of exhaustion. He stayed in bed for a week and recovered enough to help the Declaration pass ten weeks later. The Winnipeg convention was the CCF's swan song

. Even with the Declaration' s modified tone, which removed state planning and nationalization of industry as central tenets of the party's platform, the CCF suffered a crippling defeat in the 1958 federal election

, which became known as the "Diefenbaker

sweep". It was obvious to Lewis, Coldwell and the rest of the CCF executive that the CCF could not continue as it was, and, with the co-operation of the CLC, they started exploring how to broaden its appeal.

, and the CLC's executive vice-president Stanley KnowlesKnowles lost his Winnipeg seat in the "Diefenbaker Sweep", but was very quickly ushered into the CLC's executive. to merge the labour and social democratic movements into a new party. Coldwell did not want to continue as the party's national leader, because he lost his parliamentary seat in the election. Lewis persuaded him to stay on until the new party was formed. Lewis was elected party president at the July 1958 convention in Montreal, which also endorsed a motion for the executive and National Council to "enter into discussions with Canadian Labour Congress" and other like-minded groups to lay the groundwork for a new party.

as its leader in the House of Commons. During the lead-up to the 1960 CCF convention, Argue was pressing Coldwell to step down. This leadership challenge jeopardized plans for an orderly transition to the new party. Lewis and the rest of the new party's organizers opposed Argue's manoeuvres, and wanted Saskatchewan

premier Tommy Douglas

to be the new party's first leader. To prevent their plans from derailing, David Lewis attempted to persuade Argue not to force a vote at the convention on the question of the party's leadership. He was unsuccessful. There was a split between the parliamentary caucus and the party executive on the convention floor. Coldwell quit and Argue replaced him as leader.

In July 1961, the CCF became the New Democratic Party (NDP). They elected Tommy Douglas as their leader by a convincing 1391 to 380 margin over Argue. Six months later, Argue quit the party and crossed the floor to join the Liberals.

In the mid-1970s, David Lewis reflected on this incident and he concluded that he had not handled the leadership transition well:

, which was concurrently held provincially, in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario

, by the NDP's Ontario leader, Donald C. MacDonald

.

Diefenbaker's government had to call an election sometime in 1962, so there was time to plan Lewis' campaign. He had two campaign managers: his son Stephen and Gerry Caplan. One of their main strategies was to gain votes in the riding's affluent Jewish enclave in the Village of Forest Hill

. Lewis, however, was perceived by the Jewish community as an outsider because he did not take part in community events or belong to a synagogue. His opposition to the creation of the state of Israel, a result of his Bundist politics, also did not sit well with the mostly Zionist community. It took extra effort on Stephen's and Caplan's parts to convince community members that David was a legitimate Jewish voice and that he would not harm their businesses. Besides resistance from the Jewish community, in his role as party national vice-president David Lewis had to tackle the impending doctors' strike in Saskatchewan, the result of the CCF government's implementation of Medicare

. He called the province's doctors "blackmailers" for suggesting such a strike. Lewis also appeared on one of the NDP's few national television spots. He appeared on the national CTV Television Network

with Walter Pitman

to present the NDP's platform on a planned economy, in a conversation-style election broadcast. On June 18, 1962, Lewis was elected in York South, and finally became an MP. Since Tommy Douglas lost in his seat, Lewis was considered the front-runner to become house leader until Douglas entered the house in an October by-election.

|-

|New Democratic Party

|David Lewis

|align="right"|19,101||align="right"|40.42

|Liberal

|Marvin Gelber

|align="right"|15,423 ||align="right"|32.64

|Progressive Conservative

|William G. Beech

|align="right"|12,552||align="right"|26.56

|Social Credit

| Reinald Nochakoff

|align="right"| 179 ||align="right"|0.38

Lewis' first term as MP was a short one, as Diefenbaker's minority government was defeated in the April 8, 1963, general election

.In Canadian politics, if a minority government – one that does not have a majority of the elected members in the House of Commons – loses a vote of non-confidence, than the government has to call a general election. This is exactly the scenario that happened in 1963, and why Lewis had to fight another election so soon after being elected. Lewis lost in Forest Hill, as his support among its Jewish community evaporated and returned to the Liberals, who were seen as best able to contain the Social Credit Party

, which was perceived to be anti-Semitic. This was only a temporary set-back. With Diefenbaker in opposition (and unlikely to resurrect the coalition in Quebec that gave him his majority in 1958) and Social Credit a diminished force, Lewis returned to the House of Commons in the 1965 general election

. He was re-elected in the 1968 election, and became the NDP leader in the House of Commons after Douglas lost his seat. At the 1969 Winnipeg National Convention, Douglas announced that he intended to step-down as leader by 1971, which meant that Lewis became the de facto leader in the interim.

The October 1970 Quebec FLQ Crisis

put Lewis in the spotlight, as he was the only NDP MP with any roots in Quebec. He and Douglas were opposed to the October 16 implementation of the War Measures Act

. The Act, enacted previously only for wartime purposes, imposed extreme limitations on civil liberties, and gave the police and military vastly expanded powers for arresting and detaining suspects, usually with little to no evidence required. Although it was only meant to be used in Quebec, since it was federal legislation, it was in-force throughout Canada. Some police services, from outside of Quebec, took advantage of it for their own purposes, which mostly had nothing even remotely related to the Quebec situation, as Lewis and Douglas suspected. Sixteen of the 20 members of the NDP parliamentary caucus voted against the implementation of the War Measures Act in the House of Commons. They took much grief for being the only parliamentarians to vote against it. Lewis stated at a press scrum that day: "The information we do have, showed a situation of criminal acts and criminal conspiracy in Quebec. But, there is no information that there was unintended, or apprehended, or planned insurrection, which alone, would justify invoking the War Measures Act." About five years later, many of the MPs who voted to implement it regretted doing so, and belatedly honoured Douglas and Lewis for their stand against it. Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield

went so far as to say that, "Quite frankly, I've admired Tommy Douglas and David Lewis, and those fellows in the NDP for having the courage to vote against that, although they took a lot of abuse at the time....I don't brood about it. I'm not proud of it."

. Following the engineered 1970 resignation of Donald C. MacDonald, Stephen was elected leader of the Ontario New Democratic Party

. During the early-to-mid-1970s, the father-and-son-team led the two largest sections of the NDP.

In February 1968, Stephen Lewis, as a supposed representative of the Ontario NDP legislative caucus, asked the 63-year-old Tommy Douglas to step down as leader so that a younger person could take over. Donald C. MacDonald stated that Lewis was not representing the caucus, but acting on his own. Though Douglas was taken aback by the suggestion, his defeat in the ensuing election bolstered Stephen's case and on October 28, 1969, Douglas announced that he would step down as leader before the NDP's 1971 convention.

David Lewis ran to succeed Douglas as national leader. The 1971 leadership convention was a tumultuous affair. A new generation of NDP activists known as The Waffle

proposed many controversial resolutions, including nationalization of all natural resource industries and support for Quebec Sovereignty. It took the combined efforts of the NDP establishment — and the sizable trade union delegation — to vote down these resolutions, which caused many bitter debates and sharply divided the convention. Lewis, as the leading establishment figure, won the party's leadership on April 24 in a surprisingly close race that required four ballots before he could claim victory over the Waffle's James Laxer

. Laxer had been prominently featured in media coverage leading up to and during the convention. Lewis' perceived heavy-handedness in dealing with The Waffle at this and previous conventions made him many enemies, as had his involvement in most of the CCF and NDP's internal conflicts during the previous 36 years. Many members who had felt his wrath as party disciplinarian plotted their revenge against him. At his first press conference after winning the leadership, Lewis stated that he was not beholden to the Waffle, as they were soundly defeated at the convention, and that he made no promises to them. He also warned the party's Quebec wing that they could continue to theorize about possible self-determination resolutions, but that come election time they must pledge themselves to the party's newly confirmed federalist policy. He did not purge the Waffle from the NDP, but left it to his son Stephen to do in June 1972, when the party's Ontario wing resolved to disband the Waffle or kick its members out of the party if they did not comply with the disbanding order.

David Lewis led the NDP through the 1972 federal election

, during which he uttered his best known quotation, calling Canadian corporations "corporate welfare

bums". This election campaign also employed the first dedicated plane for the NDP leader's tour, dubbed "Bum Air" by reporters, because it was a slow, twin engine, turbo-prop driven Handley Page Dart Herald

. In previous campaigns, the party's leader, Tommy Douglas, had to use commercial Air Canada flights to get around during the election, with few people in his entourage.

The 1972 election returned a Liberal minority government

and elected the greatest number of NDP MPs until the 1988 "Free Trade" election, and left the NDP holding the balance of power until 1974. The NDP propped up Pierre Trudeau

's Liberal government in exchange for the implementation of NDP proposals such as the creation of Petro-Canada

as a crown corporation. Lewis wanted to topple the government in a vote of no-confidence as early as possible, because he saw no strategic advantage to supporting the Trudeau government: he believed that Trudeau would get the credit if a program was well-received, and that the NDP would be vilified if it was unpopular.

In hindsight, Lewis' no-win evaluation of the situation appears correct: the party would not be rewarded for its efforts by the electorate. In the 1974 election

, the NDP were reduced to 16 seats. Lewis lost his seat, leading him to resign as party leader in 1975. It was revealed immediately after the election that he had been battling leukemia

for about two years; he had reportedly kept everyone, including his family, unaware of his condition.

|-

|Liberal

|Ursula Appolloni

|align="right"| 12,485||align="right"|43.10

|New Democratic Party

|David Lewis

|align="right"|10,622||align="right"|36.67

|Progressive Conservative

|Paul J. Schrieder

|align="right"| 5,557||align="right"|19.18

|Independent

|Richard Sanders

|align="right"| 103||align="right"|0.04

|Marxist-Leninist

| Keith Corkhill

|align="right"|102||align="right"|0.04

|Independent

|Robert Douglas Sproule

|align="right"|97||align="right"|0.03

, with his investiture held on April 20, 1977. He was appointed to the highest level of the Order of Canada in "recognition of the contributions he has made to Labour and social reform and the deep concern he has had over the years for his adopted country." David Lewis Public School in Scarborough, Ontario

is named in his honour.

He became a professor at the Institute of Canadian Studies at Carleton University

in Ottawa during this time. In 1978, as a travel correspondent for The Toronto Star, Lewis visited Svisloch one last time, and noted that, "not one Jew now lives there." The Holocaust wiped out the town's Jewish community, and with it his extended family.

David Lewis completed the first volume, of a planned two, of his memoirs, The Good Fight: Political Memoirs 1909–1958 in 1981. He died shortly thereafter, on May 23, 1981, in Ottawa. He is the father of Stephen Lewis, a former Ontario NDP leader who in the early and mid-first decade of the 21st century was the United Nations

Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa. His other son, Michael Lewis, was a former Ontario NDP Secretary and a leading organizer in the NDP. He is also the father of Janet Solberg, president of the Ontario NDP in the 1980s. His other twin daughter is Nina Libeskind, the wife and business partner of architect Daniel Libeskind

. Stephen's son, broadcaster Avram (Avi) Lewis

, is his grandson. In 2010, his granddaughter-in-law Naomi Klein

, gave the inaugural David Lewis Lecture, sponsored by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

.

Order of Canada

The Order of Canada is a Canadian national order, admission into which is, within the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, the second highest honour for merit...

(born David Losz; June 23, or October 1909 – May 23, 1981) was a Russian-born Canadian labour lawyer and social democratic

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political ideology of the center-left on the political spectrum. Social democracy is officially a form of evolutionary reformist socialism. It supports class collaboration as the course to achieve socialism...

politician. He was national secretary of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation was a Canadian political party founded in 1932 in Calgary, Alberta, by a number of socialist, farm, co-operative and labour groups, and the League for Social Reconstruction...

(CCF) from 1936 to 1950, and one of the key architects of the New Democratic Party

New Democratic Party

The New Democratic Party , commonly referred to as the NDP, is a federal social-democratic political party in Canada. The interim leader of the NDP is Nycole Turmel who was appointed to the position due to the illness of Jack Layton, who died on August 22, 2011. The provincial wings of the NDP in...

(NDP) in 1961. In 1962, he was elected as the Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

(MP), in the Canadian House of Commons

Canadian House of Commons

The House of Commons of Canada is a component of the Parliament of Canada, along with the Sovereign and the Senate. The House of Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 308 members known as Members of Parliament...

, for the York South

York South

York South was an electoral district in Ontario, Canada, that was represented in the Canadian House of Commons from 1904 to 1979, and in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario from 1926 to 1999....

electoral district. While an MP, he was elected the NDP's national leader, where he served from 1971 to 1975. After his defeat in the 1974 federal election, he stepped down as leader and retired from politics. He spent his last years as a university professor and travel correspondent for the Toronto Star

Toronto Star

The Toronto Star is Canada's highest-circulation newspaper, based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Its print edition is distributed almost entirely within the province of Ontario...

. In retirement, he was named to the Order of Canada

Order of Canada

The Order of Canada is a Canadian national order, admission into which is, within the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, the second highest honour for merit...

for his political service. After a lengthy battle with cancer, he died in Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

in 1981.

Lewis' politics were heavily influenced by the Jewish Labour Bund, which contributed to his support of parliamentary democracy. He was an avowed anti-communist, and while a Rhodes Scholar

Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship, named after Cecil Rhodes, is an international postgraduate award for study at the University of Oxford. It was the first large-scale programme of international scholarships, and is widely considered the "world's most prestigious scholarship" by many public sources such as...

prevented communist domination of the Oxford University Labour Club

Oxford University Labour Club

Oxford University Labour Club was founded in 1919 to provide a voice for Labour Party values and for socialism and social democracy at Oxford University, England...

. In Canada, he played a major role in removing communist influence from the labour movement

Labour movement

The term labour movement or labor movement is a broad term for the development of a collective organization of working people, to campaign in their own interest for better treatment from their employers and governments, in particular through the implementation of specific laws governing labour...

.

In the CCF, he took the role of disciplinarian and dealt with internal organizational problems. He helped draft the Winnipeg Declaration

Winnipeg Declaration

The Winnipeg Declaration was the programme adopted by the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in Canada to replace the Regina Manifesto...

, which moderated the CCF's economic policies to include acceptance of capitalism, albeit subject to stringent government regulation. As the United Steelworkers of America (USW)'s legal counsel in Canada, he helped them take over the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (Mine-Mill). His involvement with the USW also led to a central role in the creation of the Canadian Labour Congress

Canadian Labour Congress

The Canadian Labour Congress, or CLC is a national trade union centre, the central labour body in English Canada to which most Canadian labour unions are affiliated.- Formation :...

in 1956.

The Lewis family has been active in socialist politics since the turn of the twentieth century, starting with David Lewis' father's involvement in the Bund in Russia, continuing with David, and followed by his eldest son, Stephen Lewis

Stephen Lewis

Stephen Henry Lewis, is a Canadian politician, broadcaster and diplomat. He was the leader of the social democratic Ontario New Democratic Party for most of the 1970s. During many of the those years as leader, his father David Lewis was simultaneously the leader of the Federal New Democratic Party...

, who led the Ontario NDP from 1970 until 1978. When David was elected the NDP's national leader in 1971, he and Stephen became one of the first father-and-son-teams to simultaneously head Canadian political parties.

The Bund and Jewish life in the Pale

David Losz was born sometime after Svisloch's first snowfall in October 1909 to Moishe Losz and his wife Rose (née Lazarovitch).His actual date of birth is unknown. When he emigrated from Russia to Canada in 1921, he did not speak English, and according to his daughter Janet Solberg June 23 was the first date that popped into his head when the immigration officer asked him when he was born. (Smith, pp.93, 542) Smith identifies October as a best guess, since the only specifics given were that he was born "right after the first snows in 1909". (Smith, pp.93, 542) His official birth date of June 23 was the one he gave the immigration officer when he arrived in Canada. Lewis's political activism began in the shtetlShtetl

A shtetl was typically a small town with a large Jewish population in Central and Eastern Europe until The Holocaust. Shtetls were mainly found in the areas which constituted the 19th century Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire, the Congress Kingdom of Poland, Galicia and Romania...

he lived in from 1909 until 1921. Svisloch was located in the Pale of Settlement

Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement was the term given to a region of Imperial Russia, in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed, and beyond which Jewish permanent residency was generally prohibited...

, the western-most region of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, in what is now Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

. After World War I it became a Polish border town, occasionally occupied by the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

during the Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic—four states in post–World War I Europe...

of the early 1920s. Jewish people were in the majority, numbering 3,500 out of Svisloch's 4,500 residents. Unlike many of the other shtetls in the Pale, it had an industrial economy based on tanning

Tanning

Tanning is the making of leather from the skins of animals which does not easily decompose. Traditionally, tanning used tannin, an acidic chemical compound from which the tanning process draws its name . Coloring may occur during tanning...

. Its semi-urban industrial population was receptive to social democratic politics and the labour movement

Labour movement

The term labour movement or labor movement is a broad term for the development of a collective organization of working people, to campaign in their own interest for better treatment from their employers and governments, in particular through the implementation of specific laws governing labour...

, as embodied by the Jewish Labour Bund.

Moishe (or Moshe) Losz was Svisloch's Bund Chairman. The Bund was an outlawed socialist party that called for overthrowing the Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

, equality for all, and national rights for the Jewish community; it functioned as both political party and labour movement. Lewis spent his formative years immersed in its culture and philosophy. The Bund's membership, although mostly ethnically Jewish, was secular humanist in practice.

Moishe and David were influenced by the Bund's political pragmatism, embodied in its maxim that "It is better to go along with the masses in a not totally correct direction than to separate oneself from them and remain a purist." David would bring this philosophy to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and New Democratic Party (NDP); in clashes between the parties' "ideological missionaries and the power pragmatists when internal debates raged about policy or action", he was in the latter camp.

When the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

and the Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War in 1920

The Polish–Soviet war erupted in 1920 in the aftermath of World War I. The root causes were twofold: a territorial dispute dating back to Polish-Russian wars in the 17–18th centuries; and a clash of ideology due to USSR's goal of spreading communist rule further west, to Europe...

were at their fiercest, in the summer of 1920, Poland invaded, and the Red Russian Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

army counter-attacked. The Bolsheviks reached the Svisloch border in July 1920. Moishe Losz openly opposed the Bolsheviks and would later be jailed by them for his opposition. When the Polish army recaptured Svisloch on August 25, 1920, they executed five Jewish citizens as "spies". Unsafe under either regime and with his family's future prospects bleak, Moishe left for Canada in May 1921, to work in his brother-in-law's Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

clothing factory. By August, he saved enough money to send for his family, including David and his siblings, Charlie and Doris.

David Lewis was a secular Jew, as was Moishe. However, his maternal grandfather, Usher Lazarovitch, was religious and, in the brief period between May and August 1921 before David emigrated, gave his grandson the only real religious training he would ever receive. David did not actively take part in a religious service again until his granddaughter Ilna's Bat Mitzvah in the late 1970s. In practice, the Lewis family, including David, his wife Sophie, and their children Janet, Stephen, and Michael, were atheists.

Early life in Canada

The family came to Canada by boat and landed in HalifaxCity of Halifax

Halifax is a city in Canada, which was the capital of the province of Nova Scotia and shire town of Halifax County. It was the largest city in Atlantic Canada until it was amalgamated into Halifax Regional Municipality in 1996...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

. They then went by rail to Montreal to meet Moishe Lewis. David Lewis was a native Yiddish speaker and understood very little English. He learned it by buying a copy of Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

' novel The Old Curiosity Shop

The Old Curiosity Shop

The Old Curiosity Shop is a novel by Charles Dickens. The plot follows the life of Nell Trent and her grandfather, both residents of The Old Curiosity Shop in London....

and a Yiddish-English dictionary. A Welsh

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

teacher at Fairmont Public School, where Lewis was a student, helped him learn English but also passed on his Welsh accent.

Lewis entered Baron Byng High School

Baron Byng High School

Baron Byng High School was located at 4251 St. Urbain Street, in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It was named after the Julian Hedworth George Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy, the Governor General of Canada from 1921 to 1926. Byng was a World War I hero at the battle of Vimy Ridge, an important battle...

in September 1924. He soon became friends with A.M. (Abe) Klein, who was to become one of Canada's leading poets. He also met Irving Layton

Irving Layton

Irving Peter Layton, OC was a Romanian-born Canadian poet. He was known for his "tell it like it is" style which won him a wide following but also made enemies. As T...

, another future major poet, to whom he acted as political mentor. Baron Byng High School was predominately Jewish because it was in the heart of Montreal's non-affluent Jewish community, and was ghetto-like because Jews were forbidden from attending many high schools.

Besides poets, at high school Lewis met Sophie Carson, who eventually became his wife. Klein, their mutual friend, introduced them. Carson was a first generation Jewish-Canadian from a religious family. Her father did not approve of Lewis, because he was a recent immigrant to Canada, and in Carson's father's opinion had little to no possibility of success.

After high school, Lewis spent five years at McGill University

McGill University

Mohammed Fathy is a public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The university bears the name of James McGill, a prominent Montreal merchant from Glasgow, Scotland, whose bequest formed the beginning of the university...

in Montreal: four in arts, and one in law. While there, he helped found the Montreal branch of the Young People's Socialist League

Young People's Socialist League

The Young People's Socialist League , founded in 1989, is the official youth arm of the Socialist Party USA. The group's membership consists of those democratic socialists under the age of 30, and its political activities tend to concentrate on increasing the voter turnout of young democratic...

. He gave lectures sponsored by this anti-communist socialist club, and was its nominal leader. One of his favourite professors was Canadian humorist, and noted Conservative party proponent, Stephen Leacock

Stephen Leacock

Stephen Butler Leacock, FRSC was an English-born Canadian teacher, political scientist, writer, and humorist...

, whom Lewis liked more for his personality than for his discipline, economics.

In his third year, Lewis founded The McGilliad campus magazine. It published many of his anti-communist views, though the December 1930 issue included an article he wrote expressing his approval of the Russian Revolution and calling for a greater understanding of the Soviet Union; throughout his career, he would attack communism, but would always have a sympathy for the 1917 revolutionaries. Also at McGill, Lewis met and worked with prominent Canadian socialists like F.R. Scott, Eugene Forsey

Eugene Forsey

Eugene Alfred Forsey, served in the Canadian Senate from 1970 to 1979. He was considered to be one of Canada's foremost constitutional experts.- Biography :...

, J. King Gordon

J. King Gordon

John King Gordon, CM was a Canadian editor, diplomat, and academic.Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, the son of Charles William Gordon, he received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Manitoba in 1920. A Rhodes scholar, he studied at Oxford University from 1920 to 1921. He was a United...

, and Frank Underhill

Frank Underhill

Frank Hawkins Underhill, was a Canadian historian, social critic and political thinker.Frank Underhill, born in Stouffville, Ontario, was educated at the University of Toronto and the University of Oxford where he was a member of the Fabian Society...

. He would work with all of them again in the 1940s and 50s in the CCF.

Rhodes Scholarship and Oxford

With Scott's encouragement, Lewis applied for a Rhodes ScholarshipRhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship, named after Cecil Rhodes, is an international postgraduate award for study at the University of Oxford. It was the first large-scale programme of international scholarships, and is widely considered the "world's most prestigious scholarship" by many public sources such as...

during his first year at law school. The interviews for the Quebec representative were conducted in Montreal. The examining board included the then-president of the Canadian Pacific Railway

Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway , formerly also known as CP Rail between 1968 and 1996, is a historic Canadian Class I railway founded in 1881 and now operated by Canadian Pacific Railway Limited, which began operations as legal owner in a corporate restructuring in 2001...

(CPR), Sir Edward Beatty

Edward Wentworth Beatty

Sir Edward Wentworth Beatty, GBE was a Canadian lawyer, university chancellor, and businessman. He was president of the Canadian Pacific Railway from 1918 to 1943, chancellor of Queen's University from 1919 to 1923, and chancellor of McGill University from 1920 to 1943.He studied at Upper Canada...

. In response to a question about what he would do if he became prime minister, Lewis stated that he would nationalize the CPR. Despite this answer and his socialist views in general, his responses to the board's cross-examination satisfied them that he was not a communist, and they awarded him the scholarship.

Political involvement

When David Lewis entered Lincoln CollegeLincoln College, Oxford

Lincoln College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is situated on Turl Street in central Oxford, backing onto Brasenose College and adjacent to Exeter College...

, Oxford, in 1932, he immediately took a leadership role in the university's socialist-labour circles. Michael Foot

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot, FRSL, PC was a British Labour Party politician, journalist and author, who was a Member of Parliament from 1945 to 1955 and from 1960 until 1992...

, the future leader of the British Labour Party, mentioned in an interview that Lewis was,

When Lewis came to Oxford, the Labour Club

Oxford University Labour Club

Oxford University Labour Club was founded in 1919 to provide a voice for Labour Party values and for socialism and social democracy at Oxford University, England...

was a tame organization adhering to Christian activism

Social Gospel

The Social Gospel movement is a Protestant Christian intellectual movement that was most prominent in the early 20th century United States and Canada...

, or genteel socialist theories like those expressed by R.H. Tawney in his book The Acquisitive Society. Lewis' modified Bundist

Bundism

Bundism is a Jewish socialist and secular movement, which originates from the General Jewish Labour Bund founded in the Russian empire in 1897. Bundism was an important component of the social democratic movement in the Russian empire until it was violently suppressed by the Communist party after...

interpretation of Marxism, which Smith labels "Parliamentary Marxism", ignited renewed interest in the club after the disappointment of Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government.

The Oxford newspaper Isis

Isis magazine

The Isis Magazine was established at Oxford University in 1892 . Traditionally a rival to the student newspaper Cherwell, it was finally acquired by the latter's publishing house, OSPL, in the late 1990s...

noted Lewis' leadership ability at this early stage in his career. In its February 7, 1934, issue, while Lewis was president, they wrote of the club: "The energy of these University Socialists is almost unbelievable. If the Socialist movement as a whole is anything like as active as they are, then a socialist victory at the next election is inevitable."

In February 1934, British fascist William Joyce

William Joyce

William Joyce , nicknamed Lord Haw-Haw, was an Irish-American fascist politician and Nazi propaganda broadcaster to the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He was hanged for treason by the British as a result of his wartime activities, even though he had renounced his British nationality...

(Lord Haw Haw) visited Oxford. Lewis and future Ontario CCF

Ontario New Democratic Party

The Ontario New Democratic Party or , formally known as New Democratic Party of Ontario, is a social democratic political party in Ontario, Canada. It is a provincial section of the federal New Democratic Party. It was formed in October 1961, a few months after the federal party. The ONDP had its...

leader Ted Jolliffe

Ted Jolliffe

Edward Bigelow "Ted" Jolliffe, QC was a Canadian social democratic politician and lawyer from Ontario. He was the first leader of the Ontario section of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and leader of the Official Opposition in the Ontario Legislature during the 1940s and 1950s...

organized a noisy protest by planting Labour Club members in the dance hall where Joyce was speaking and having groups of two and three of them leave at a time, making much noise on the creaking wooden floors. They were successful in drowning out Joyce, and he did not complete his speech. Afterwards, a street fight erupted between Joyce's Blackshirt supporters and members of the Labour Club, including Lewis.

Lewis prevented the communists from making inroads at Oxford. Ted Jolliffe stated "there was a difference between his speeches at the Union and his speeches at the Labour Club. His speeches at the Union had more humour in them; the atmosphere was entirely different. But his speeches at the Labour Club were deadly serious ... His influence at the Labour Club, more than anyone else's, I think, explains the failure of the Communists to make headway there. There were so many naive people around who could have been taken in." He increased the Labour Club's membership by three quarters by the time he left.

In accordance with Bundism, Lewis rejected violent revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

. The Bund insisted that the revolution should be through democratic means, as Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

had judged possible in the late 1860s, and that democracy should prevail afterwards. Influenced by Fabianism, Lewis became an incrementalist in his approach to replacing non-socialist governments. As Lewis biographer Cameron Smith points out:

Lewis was a prominent figure in the British Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

, which, in emphasizing parliamentary action and organizational prowess, took an approach similar to the Bund's. Upon his 1935 graduation, the party offered him a candidacy in a safe seat

Safe seat

A safe seat is a seat in a legislative body which is regarded as fully secured, either by a certain political party, the incumbent representative personally or a combination of both...

in the British House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

. This left Lewis with a difficult decision: whether to stay in England or go home to Canada. If he had stayed in England, he likely would have been a partner in a prominent London law firm associated with Stafford Cripps

Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour politician of the first half of the 20th century. During World War II he served in a number of positions in the wartime coalition, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union and Minister of Aircraft Production...

and become a cabinet minister the next time Labour formed a government. Cripps, then a prominent barrister and Labour Party official, was grooming Lewis to be Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

. Lewis' other choice was to return to Montreal and help build the fledgling Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), with no guarantee of success. A personal note from J. S. Woodsworth

J. S. Woodsworth

James Shaver Woodsworth was a pioneer in the Canadian social democratic movement. Following more than two decades ministering to the poor and the working class, J. S...

, dated June 19, 1935, asked Lewis to take this latter option; in the end, he did.

Oxford Union

Besides his political involvement, Lewis was active with the Oxford UnionOxford Union

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to simply as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford, Britain, whose membership is drawn primarily but not exclusively from the University of Oxford...

, probably the most prestigious and important debating club in the English-speaking world. His first debate, in January 1933, was on the resolution "That the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

is a menace to International good will"; Lewis was one of the participants for the "Aye" side. They lost.

The February 9, 1933, debate brought Lewis some level of early prominence. The resolution was "That this House will under no circumstances fight for its King or Country

The King and Country debate

The King and Country debate was a discussion at the Oxford Union debating society on 9 February 1933 of the resolution: "That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country". It was passed by 275 votes to 153, and became one of the most well-known and notorious debates...

" and was so controversial that it was news around the British Empire and beyond. Lewis again spoke for the "Aye" side. They won overwhelmingly and caused a newspaper uproar throughout the Empire. The Times of London entered the fray by pooh-poohing those who took the Union and their motion seriously.

Lewis became a member of the Union's Library Committee on March 9, 1933, and its treasurer in March 1934. After two failed attempts, he was narrowly elected president in late November 1934. He was president during the Hilary term

Hilary term

Hilary Term is the second academic term of Oxford University's academic year. It runs from January to March and is so named because the feast day of St Hilary of Poitiers, 14 January, falls during this term...

, from the beginning of January until the end of April 1935. The Isis commented that "... David Lewis ... will be, beyond question, the least Oxonian person ever to the lead the Society. In appearance, background, and intellectual outlook he is a grim antithesis to all the suave, slightly delicate young men who for generations have sat on the Union rostrum ..."

Return to Canada

Sophie Carson had accompanied Lewis to Oxford, and they wed August 15, 1935, shortly after their return. The wedding took place in his parents' home; though a rabbi officiated, most traditional Jewish practices were not observed.In 1935 David Lewis became the National Secretary of the CCF. As Smith puts it:

Into this political whirlwind stepped David. A centralist in a nation that was decentralizing. A socialist in a country that voted solidly capitalist. A campaigner for a party with no money, facing two parties each of which was big, powerful, and affluent. A professional, in a party of amateurs who mostly thought of themselves as a movement, not a party. An anti-Communist at a time when Canadian Communists were about to enter their heyday. A publicist seeking a unified voice for a party riven with dissent. An organizer whose leader, J.S. Woodsworth, really didn't believe in organization, thinking that the CCF should remain a loosely knit, co-operative association and believed this so implicitly that when it came time to appoint Lewis full-time to the job of national secretary [in 1938] he resisted, fearing the CCF would lose its spontaneity.

That Lewis not only survived, but prevailed is a testament to his skill and perseverance.

Most of the founders of the CCF – including Woodsworth, Tommy Douglas

Tommy Douglas

Thomas Clement "Tommy" Douglas, was a Scottish-born Baptist minister who became a prominent Canadian social democratic politician...

, M. J. Coldwell

Major James Coldwell

Major James William Coldwell, , usually known as M.J. , was a Canadian social democratic politician, and leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party from 1942 to 1960. He was born in England, and immigrated to Canada in 1910...

, and Stanley Knowles

Stanley Knowles

Stanley Howard Knowles, PC, OC was a Canadian parliamentarian. Knowles represented the riding of Winnipeg North Centre from 1942 to 1958 on behalf of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and again from 1962 to 1984 representing the CCF's successor, the New Democratic Party .Knowles was widely...

, – were informed by the Social Gospel

Social Gospel

The Social Gospel movement is a Protestant Christian intellectual movement that was most prominent in the early 20th century United States and Canada...

, to which Lewis, with his Marxist socialism balanced by the Bund's democratic principles, felt an affinity. Both the Bund and the Social Gospel were focused on the material present rather than the afterlife. Both called on people to change their environment for the better rather than hoping that God might do it for them. Social justice, the brotherhood of man, and moral self-improvement were common to both.

It became obvious after the October 1937 Ontario election

Ontario general election, 1937

The Ontario general election, 1937 was held on October 6, 1937, to elect the 90 Members of the 20th Legislative Assembly of Ontario . It was the 20th general election held in the Province of Ontario, Canada....

that the CCF needed an image change; it was seen by the electorate as too far left. F.R. Scott pointed this out to Lewis in a letter, recommended moderating some of the party's policies, and advised that "... in the political arena we must find our friends among the near right."

In August 1938, Lewis quit his job at the Ottawa law firm of Smart and Biggar to work full-time as the CCF National Secretary. His starting salary was $1,200 per year, a low sum of money, even at that time, for job with so much responsibility.

Trying to create an organization

As National Secretary, Lewis emphasized organization over ideology and forging links to unions. He worked to moderate the party's image and downplay the Regina ManifestoRegina Manifesto

The Regina Manifesto was the programme of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and was adopted at the first national convention of the CCF held in Regina, Saskatchewan in 1933. The primary goal of the "Regina Manifesto" was to eradicate the system of capitalism and replace it with a planned...

's more radical language, which seemed to scare off moderate voters. The offending language included "No CCF government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning ..." Lewis, federal leader M.J. Coldwell, and Clarie Gillis

Clarence Gillis