Cyprus dispute

Encyclopedia

The Cyprus dispute is the result of the ongoing conflict between the Republic of Cyprus and Turkey

, over the Turkish occupied northern part of Cyprus.

Initially, with the annexation of the island by the British Empire

, the "Cyprus dispute" was identified as the conflict between the people of Cyprus and the British Crown

regarding the Cypriots' demand for self determination. The dispute however was finally shifted from a colonial dispute to an ethnic dispute between the Turkish and the Greek islanders. The international complications of the dispute stretch far beyond the boundaries of the island of Cyprus itself and involve the guarantor powers (Turkey

, Greece

, and the United Kingdom

alike), along with the United States

, the United Nations

and the European Union

.

With the invasion

of 1974 (condemned by UN Security Council Resolutions as legally invalid), Turkey occupied the northern part of the internationally recognised Republic of Cyprus, and later upon those territories the Turkish Cypriot

community unilaterally declared independence forming the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a sovereign entity that lacks international recognition-with the exception of Turkey with which TRNC enjoys full diplomatic relations.

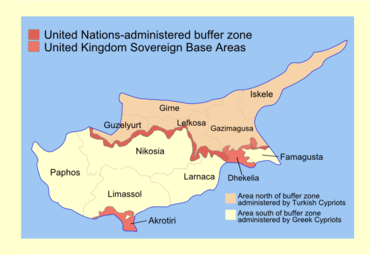

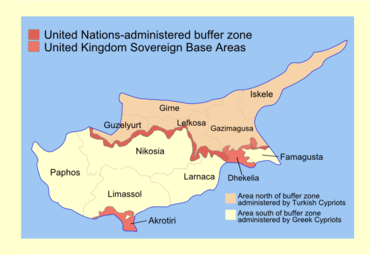

After the two communities and the guarantor countries have committed themselves in finding a peaceful solution over the dispute, the United Nations have since created and maintained a buffer zone (the "Green Line

") to avoid any further intercommunal tensions and hostilities. This zone separates the Greek Cypriot-controlled south from the Turkish Cypriot-controlled north.

Cyprus experienced an uninterrupted Greek

presence on the island dating from the arrival of Mycenaeans

around 1100 BC, when the burials began to take the form of long dromos. The Greek population of Cyprus survived through multiple conquerors, including Egyptian and Persian rule. In the 4th century BC, Cyprus was conquered by Alexander the Great and then ruled by the Ptolemaic Egypt

until 58 BC, when it was incorporated into the Roman Empire

. After an interval of Islam Khalifate (643-966), the island returned to Roman rule until the 12th century. After an occupation by the Knights Templar

and the rule of Isaac Komnenos

, the island in 1192 came under the rule of the Lusignan family, who established the Kingdom of Cyprus

. In February 1489 it was seized by the Republic of Venice

. Between September 1570 and August 1571 it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire

, starting three centuries of Turkish rule over Cyprus.

Starting in the early nineteenth century, ethnic Greeks of the island sought to bring about an end to almost 300 years of Ottoman rule and unite Cyprus with Greece

. The United Kingdom took administrative control of the island in 1878, to prevent Ottoman positions from falling under Russian control following the Cyprus Convention

, which lead to the call for union (enosis

) to grow louder. Under the terms of the agreement reached between Britain and the Ottoman Empire

, the island remained an Ottoman territory.

The Christian

Greek-speaking inhabitants of the island welcomed the arrival of the British as a chance to voice their demands for union with Greece: enosis.

When the Ottoman Empire entered World War I

on the side of the Central Powers

, Britain renounced the agreement and all Turkish claims over Cyprus and declared the island a British colony. In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Constantine I of Greece

on condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British, which he declined.

. Turkish Cypriots consistently opposed the idea of union with Greece.

In 1925 Britain declared Cyprus to be a Crown Colony

. In the years that followed, the determination for enosis continued. In 1931 this led to open revolution. A riot resulted in the death of six civilians, injuries to others and the burning of the British Government House in Nicosia

. In the months that followed, about 2,000 people were convicted of crimes in connection with the struggle for union with Greece. Britain reacted by imposing harsh restrictions. Military reinforcements were dispatched to the island and the constitution suspended. A special "epicourical" (reserve) police force was formed consisting of only Turkish Cypriots, press restrictions instituted and political parties banned. Two bishops and eight other prominent citizens directly implicated in the conflict were exiled. Municipal elections were suspended, and until 1943 all municipal officials were appointed by the government. The governor was to be assisted by an Executive Council, and two years later an Advisory Council was established; both councils consisted only of appointees and were restricted to advising on domestic matters only. In addition, the flying of Greek

or Turkish flags

or the public display of portraits of Greek or Turkish heroes was forbidden.

The struggle for enosis was put on hold during World War II

. In 1946, the British government announced plans to invite Cypriots to form a Consultative Assembly to discuss a new constitution. The British also allowed the return of the 1931 exiles. Instead of reacting positively, as expected by the British, the Greek Cypriot military hierarchy reacted angrily because there had been no mention of enosis. The Cypriot Orthodox Church

had expressed its disapproval, and Greek Cypriots declined the British invitation, stating that enosis was their sole political aim. The efforts by Greeks to bring about enosis now intensified, helped by active support of the Church of Cyprus, which was the main political voice of the Greek Cypriots at the time. However, it was not the only organization claiming to speak for the Greek Cypriots. The Church's main opposition came from the Cypriot Communist Party (officially the Progressive Party of the Working People; Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού; or AKEL), which also wholeheartedly supported the Greek national goal of enosis. However the British military forces and Colonial administration in Cyprus did not see the pro-Soviet communist party as a viable partner.

By 1954 a number of Turkish mainland institutions were active in the Cyprus issue such as the National Federation of Students, the Committee for the Defence of Turkish rights in Cyprus, the Welfare Organisation of Refugees from Thrace and the Cyprus Turkish Association. Above all, the Turkish trade unions were to prepare the right climate for the main Turkish goal, the division of the island (taksim) into Greek and Turkish parts, thus keeping the British military presence and installations on the island intact. By this time a special Turkish Cypriot paramilitary organisation Turkish Resistance Organization

(TMT) was also established which was to act as a counter balance to the Greek Cypriot enosis fighting organisation of EOKA

.

In 1950, Michael Mouskos, Bishop Makarios of Kition (Larnaca), was elevated to Archbishop Makarios III

of Cyprus. In his inaugural speech, he vowed not to rest until union with "mother Greece" had been achieved. In Athens

, enosis was a common topic of conversation, and a Cypriot native, Colonel George Grivas

, was becoming known for his strong views on the subject. In anticipation of an armed struggle to achieve enosis, Grivas visited Cyprus in July 1951. He discussed his ideas with Makarios but was disappointed by the archbishop's contrasting opinion as he proposed a political struggle rather than an armed revolution against the British. From the beginning, and throughout their relationship, Grivas resented having to share leadership with the archbishop. Makarios, concerned about Grivas's extremism from their very first meeting, preferred to continue diplomatic efforts, particularly efforts to get the United Nations

involved. The feelings of uneasiness that arose between them never dissipated. In the end, the two became enemies. In the meantime, in August [Papagos Government] 1954, Greece's UN representative formally requested that self-determination for the people of Cyprus be included on the agenda of the General Assembly's next session. Turkey rejected the idea of the union of Cyprus and Greece. Turkish Cypriot community opposed Greek Cypriot enosis movement, as under British rule the Turkish Cypriot minority status and identity were protected. Turkish Cypriot identification with Turkey had grown stronger in response to overt Greek nationalism of Greek Cypriots, and after 1954 the Turkish government had become increasingly involved. In the late summer and early autumn of 1954, the Cyprus problem intensified. On Cyprus the colonial government threatened publishers of seditious literature with up to two years imprisonment. In December the UN General Assembly announced the decision "not to consider the problem further for the time being, because it does not appear appropriate to adopt a resolution on the question of Cyprus." Reaction to the setback at the UN was immediate and violent, resulting in the worst rioting in Cyprus since 1931.

). On April 1, 1955, EOKA

opened an armed campaign against British rule in a well-coordinated series of attacks on police, military, and other government installations in Nicosia

, Famagusta

, Larnaca

, and Limassol

. This resulted in the deaths of over 100 British servicemen and personnel and some Greek Cypriots suspected of collaboration. As a result of this a number of Greek Cypriots began to leave the police. This however did not affect the Colonial police force as they had already created the solely Turkish Cypriot (Epicourical) reserve force to fight EOKA paramilitaries. At the same time, it led to tensions between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities. In 1957 the Turkish Resistance Organization (Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı TMT

), which had already been formed to protect the Turkish Cypriots from EOKA took action. In response to the growing demand for enosis, a number of Turkish Cypriots became convinced that the only way to protect their interests and identity of the Turkish Cypriot population in the event of enosis would be to divide the island - a policy known as taksim ("partition" in Turkish

borrowed from (تقسیم)"Taghsim" in Arabic

) - into a Greek sector in the south and a Turkish sector in the north only.

By now the island was on the verge of civil war. Several attempts to present a compromise settlement had failed. Therefore, beginning in December 1958, representatives of Greece and Turkey, the so called "mother lands" opened discussions of the Cyprus issue. Participants for the first time discussed the concept of an independent Cyprus, i.e., neither enosis nor taksim. Subsequent talks always headed by the British yielded a so called compromise agreement supporting independence, laying the foundations of the Republic of Cyprus. The scene then naturally shifted to London, where the Greek and Turkish representatives were joined by representatives of the Greek Cypriots, the Turkish Cypriots (represented by Arch. Makarios and Dr Fazil Kucuk with no significant decision making power), and the British. The Zurich-London agreements that became the basis for the Cyprus constitution of 1960 were supplemented with three treaties - the Treaty of Establishment, the Treaty of Guarantee, and the Treaty of Alliance. The general tone of the agreements was one of keeping the British sovereign bases and military and monitoring facilities intact. Some Greek Cypriots, especially members of organizations such as EOKA

, expressed disappointment because enosis had not been attained. In a similar way some Turkish Cypriots especially members of organizations such as TMT expressed their disappointment as they had to postpone their target for taksim, however most Cypriots that were not influenced by the three so called guarantor powers (Greece, Turkey, and Britain), welcomed the agreements and set aside their demand for enosis and taksim. According to the Treaty of Establishment, Britain retained sovereignty over 256 square kilometers, which became the Dhekelia Sovereign Base Area

, to the northwest of Larnaca

, and the Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area

to the southwest of Limassol

.

Cyprus achieved independence on August 16, 1960.

with a Greek Cypriot president

and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president. General executive authority was vested in a council of ministers

with a ratio of seven Greeks to three Turks. (The Greek Cypriots represented 78% of the population and the Turkish Cypriots 18%. The remaining 4% was made up by the three minority communities: the Latins, Maronites and Armenians

.) A House of Representatives

of fifty members, also with a seven-to-three ratio, were to be separately elected by communal balloting on a universal suffrage

basis. In addition, separate Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Communal Chambers were provided to exercise control in matters of religion, culture, and education. According to Article 78(2) any law imposing duties or taxes shall require a simple majority of the representatives elected by the Greek and Turkish communities respectively taking part in the vote. Legislation on other subjects was to take place by simple majority but again the President and the Vice-President had the same right of veto—absolute on foreign affairs, defence and internal security, delaying on other matters—as in the Council of Ministers. The judicial system would be headed by a Supreme Constitutional Court, composed of one Greek Cypriot and one Turkish Cypriot and presided over by a contracted judge from a neutral country. The Constitution of Cyprus, whilst establishing an Independent and sovereign Republic, was, in the words of de Smith

, an authority on Constitutional Law; "Unique in its tortuous complexity and in the multiplicity of the safeguards that it provides for the principal minority; the Constitution of Cyprus stands alone among the constitutions of the world"

Within a short period of time the first disputes started to arise between the two communities. Issues of contention included taxation and the creation of separate municipalities. Because of the legislative veto system, this resulted in a lockdown in communal and state politics in many cases.

Repeated attempts to solve the disputes failed. Eventually, on November 30, 1963, Makarios

put forward to the three guarantors a thirteen-point proposal designed, in his view, to eliminate impediments to the functioning of the government. The thirteen points involved constitutional revisions, including the abandonment of the veto power by both the president and the vice president. Turkey initially rejected it (although later in future discussed the proposal). A few days later, on December 21, 1963 fighting erupted between the communities in Nicosia

. In the days that followed it spread across the rest of the island. At the same time, the power-sharing government collapsed. How this happened is one of the most contentious issues in modern Cypriot history. The Greek Cypriots argue that the Turkish Cypriots withdrew in order to form their own administration. The Turkish Cypriots maintain that they were forced out. Many Turkish Cypriots chose to withdraw from the government. However, in many cases those who wished to stay in their jobs were prevented from doing so by the Greek Cypriots. Also, many of the Turkish Cypriots refused to attend because they feared for their lives after the recent violence that had erupted. There was even some pressure from the TMT

as well. In any event, in the days that followed the fighting a frantic effort was made to calm tensions. In the end, on December 27, 1963, an interim peacekeeping force, the Joint Truce Force, was put together by Britain

, Greece and Turkey. This held the line until a United Nations peacekeeping force, UNFICYP

, was formed following United Nations Security Council Resolution 186

, passed on March 4, 1964.

, then the UN Secretary-General, appointed Sakari Tuomioja

, a Finnish

diplomat. While Tuomioja viewed the problem as essentially international in nature and saw enosis as the most logical course for a settlement, he rejected union on the grounds that it would be inappropriate for a UN official to propose a solution that would lead to the dissolution of a UN member state. The United States held a differing view. In early June, following another Turkish threat to intervene, Washington launched an independent initiative under Dean Acheson

, a former Secretary of State. In July he presented a plan to unite Cyprus with Greece. In return for accepting this, Turkey would receive a sovereign military base on the island. The Turkish Cypriots would also be given minority rights, which would be overseen by a resident international commissioner. Makarios

rejected the proposal, arguing that giving Turkey territory would be a limitation on enosis and would give Ankara too strong a say in the island’s affairs. A second version of the plan was presented that offered Turkey a 50-year lease on a base. This offer was rejected by the Greek Cypriots and by Turkey. After several further attempts to reach an agreement, the United States was eventually forced to give up its effort.

Following the sudden death of Ambassador Tuomioja in August, Galo Plaza

was appointed Mediator. He viewed the problem in communal terms. In March 1965 he presented a report criticising both sides for their lack of commitment to reaching a settlement. While he understood the Greek Cypriot aspiration of enosis, he believed that any attempt at union should be held in voluntary abeyance. Similarly, he considered that the Turkish Cypriots should refrain from demanding a federal solution to the problem. Although the Greek Cypriots eventually accepted the report, despite of its opposition to immediate enosis, Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots rejected the plan, calling on Plaza to resign on the grounds that he had exceeded his mandate by advancing specific proposals. He was simply meant to broker an agreement. But the Greek Cypriots made it clear that if Galo Plaza resigned they would refuse to accept a replacement. U Thant was left with no choice but to abandon the mediation effort. Instead he decided to make his Good Offices available to the two sides. By resolution 186 of 4 March 1964 and a Mediator was appointed. In his Report (S/6253, A/6017, 26 March 1965), the Mediator, Dr Gala Plaza, criticized the 1960 legal framework, and proposed necessary amendments which were rejected by Turkey, a fact which resulted in serious deterioration of the situation with constant threats by Turkey against the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Cyprus, necessitating a series of UN Resolutions calling, inter alia, for respect of the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Cyprus.

The Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1965, described the policy of the Turkish Cypriot leaders in this way: "The Turkish Cypriot leaders have adhered to a rigid stand against any measures which might involve having members of the two communities live and work together, or which might place Turkish Cypriots in situations where they would have to acknowledge the authority of Government agents. Indeed, since the Turkish Cypriot leadership is committed to physical and geographical separation of the communities as a political goal, it is not likely to encourage activities by Turkish Cypriots which may be interpreted as demonstrating the merits of an alternative policy. The result has been a seemingly deliberate policy of self-segregation by the Turkish Cypriots"Report S/6426

The end of the mediation effort was effectively confirmed when, at the end of the year, Plaza resigned and was not replaced.

In March 1966, a more modest attempt at peacemaking was initiated under the auspices of Carlos Bernades, the Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Cyprus. Instead of trying to develop formal proposals for the parties to bargain over, he aimed to encourage the two sides agree to settlement through direct dialogue. However, ongoing political chaos in Greece prevented any substantive discussions from developing. The situation changed the following year. On 21 April 1967, a coup d'état

in Greece brought to power a military administration. Just months later, in November 1967, Cyprus witnessed its most severe bout of intercommunal fighting since 1964. Responding to a major attack on Turkish Cypriot villages in the south of the island, which left 27 dead, Turkey bombed Greek Cypriot forces and appeared to be readying itself for an intervention. Greece was forced to capitulate. Following international intervention, Greece agreed to recall General George Grivas

, the Commander of the Greek Cypriot National Guard

and former EOKA leader, and reduce its forces on the island. Capitalising on the weakness of the Greek Cypriots, the Turkish Cypriots proclaimed their own provisional administration on 28 December 1967. Makarios immediately declared the new administration illegal. Nevertheless, a major change had occurred. The Archbishop, along with most other Greek Cypriots, began to accept that the Turkish Cypriots would have to have some degree of political autonomy. It was also realised that unification of Greece and Cyprus was unachievable under the prevailing circumstances.

In May 1968, intercommunal talks began between the two sides under the auspices of the Good Offices of the UN Secretary-General. Unusually, the talks were not held between President Makarios and Vice-President Kucuk. Instead they were conducted by the presidents of the communal chambers, Glafcos Clerides and Rauf Denktaş

. Again, little progress was made. During the first round of talks, which lasted until August 1968, the Turkish Cypriots were prepared to make several concessions regarding constitutional matters, but Makarios refused to grant them greater autonomy in return. The second round of talks, which focused on local government, was equally unsuccessful. In December 1969 a third round of discussion started. This time they focused on constitutional issues. Yet again there was little progress and when they ended in September 1970 the Secretary-General blamed both sides for the lack of movement. A fourth and final round of intercommunal talks also focused on constitutional issues, but again failed to make much headway before they were forced to a halt in 1974.

Timeline of the 1974 Invasion of Cyprus

After 1967, tensions between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots subsided. Instead, the main source of tension on the island came from factions within the Greek Cypriot community. Although Makarios

had effectively abandoned enosis in favour of an ‘attainable solution’, many others continued to believe that the only legitimate political aspirations for Greek Cypriots was union with Greece. In September 1971 Grivas secretly returned to the island and formed EOKA-B

, a vehemently pro-union organisation. In early 1974 Grivas died and EOKA-B fell under the direct control of Taxiarkhos

Dimitrios Ioannides

, the new head of the Junta

in Athens

. Ioannides was determined to overthrow Makarios. Fearing the consequences of such a step, in early July 1974 Makarios

wrote an open letter to the military dictatorship requesting that all Greek officers be removed from the island. On July 15, Ioannides replied through a coup of the Cyprus National Guard which resulted in Makarios being deposed.

After failing to secure British support for a joint intervention under the Treaty of Guarantee, Bülent Ecevit

, the Turkish prime minister, decided to act unilaterally. On July 20 Turkey ordered a military invasion of the island (Turkish invasion of Cyprus

). Within two days Turkish forces had established a narrow corridor linking the north coast with Nicosia. The intervention led to turmoil in Greece. On July 23 the military Junta collapsed.

Two days later formal peace talks were convened in Geneva

between Greece, Turkey and Britain. Over the course of the following five days Turkey agreed to halt its advance on the condition that it would remain on the island until a political settlement was reached between the two sides. On August 8 another round of discussion was held in Geneva, Switzerland. Unlike before, this time the talks involved the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. During the discussions the Turkish Cypriots, supported by Turkey, insisted on some form of geographical separation between the two communities. Makarios

refused to accept the demand, insisting that Cyprus must remain a unitary state. Despite efforts to break the deadlock, the two sides refused to budge. On August 14, Turkey demanded from Clerides acceptance of a proposal for a federal state

, in which the Turkish Cypriot community (who, at that time, comprised about 18% of the population and owned about 10% of the land) would have received 34% of the island. Clerides asked for 36 to 48 hours to consult with the Cypriot and Greek governments, but Turkey refused to grant any consultation time, effectively ending the talks. Within hours, Turkey had resumed its second offensive. By the time a new, and permanent, ceasefire was called 36 per cent of the island was under the control of the Turkish military. The partition was marked by the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus

or "green line" running east to west across the island.

The effect of the division was catastrophic for all concerned. Thousands of Greek and Turkish Cypriots had been killed, wounded or missing. A further two hundred thousand Greek and Turkish Cypriots had been displaced. In addition to the entire north coast (Kerynia, Morfou) and the Karpas peninsula, the Greek Cypriots were also forced to flee the eastern port city of Famagusta

. The vast majority of the Turkish occupied area was predominantly populated and owned by Greek Cypriots prior to 1974.

In the process about 160,000 - 200,000 Greek Cypriots who made up 82% of the population in the north became refugees; many of them fleeing at the word of the approaching Turkish army. Since 1974, the ceasefire line separates the two communities on the island, and is commonly referred to as the Green Line. The United Nations consented to the transfer of the remainder of the 51,000 Turkish Cypriots that were trapped in the south to settle in the north, if they wished to do so. Many of them had previously moved to the areas under UK sovereign control awaiting permission to be transferred to the areas under Turkish control.

During the operation, EOKA-B committed the massacres of Tohni and Maratha, Santalaris and Aloda

.

and certainly agreement came close, but the Makarios government could not accept de jure separateness, which would have denied the principle of the unitary, if bi-communal, state.

Inter-communal strife was also overshadowed during this period by a serious rift on the Greek side, between Makarios and the enosist National Front supported by the Greek junta. Makarios had now become an obstacle to enosis. An attempt was made on his life, and Grivas returned in 1971 to head a new organisation, EOKA-B, with Makarios, rather than the Turkish-Cypriots, in its sight.

Makarios was told from Athens to dismiss his foreign minister and to regard Athens as the National Centre. Makarios rallied supporters successfully against attempts to remove him. He was still popular in Cyprus.

Matters became worse when a new junta came to power in September 1973, and there was less relief from rightist pressure than might have been expected when Grivas died suddenly in January 1974. The pressure mounted until a peace operation in July 1974 allegedly led by a 'hammer of the Turks' Nikos Sampson

, overthrew Makarios, who managed to flee the country via a British base. For Turkey this raised the spectre of Greek control of Cyprus.

Turkey intervened on 20 July 1974, having the right to do so unilaterally as concerted action had not proved possible. Under the 1960 Treaty, Turkey's sole object could be to re-establish the state of affairs guaranteed by the basic articles of the 1960 Constitution. The coup d'état was said by Makarios himself to be an attempt to extend Greek dictatorship to the island.

Launched with relatively few troops, the Turkish landing had limited success at first, and resulted everywhere on the island in the occupation of Turkish-Cypriot enclaves by the Greek forces. After securing a more or less satisfactory bridgehead Turkish forces agreed to a cease-fire on 23 July 1974. The same day civilian government under Karamanlis took office in Athens, the day the Sampson coup collapsed. Glafcos Clerides became the Acting President in absence still of Makarios.

A conference of the guarantor powers, Greece, Turkey and Britain, met in Geneva on 25 July. Meanwhile Turkish troops did not refrain from extending their positions, as more Turkish-Cypriot enclaves were occupied by Greek forces. A new cease-fire line was agreed. On 30 July the powers agreed that the withdrawal of Turkish troops from the island should be linked to a `just and lasting settlement acceptable to all parties concerned'. The declaration also spoke of `two autonomous administrations -that of Greek-Cypriot community and that of the Turkish-Cypriot community'.

These plans were presented to the conference on 13 August by the Turkish Foreign Minister, Turan Güneş. Clerides wanted thirty-six to forty-eight hours to consider the plans, but Güneş demanded an immediate response. This was regarded as unreasonable by the Greeks, the British and the Americans who were in close consultation. Nevertheless, the next day, the Turkish forces extended their control to some 36 per cent of the island. they were afraid that delay would turn international opinion strongly against them if Greek spoiling tactics were given a chance and they were determined to come to the rescue of greatly threatened Turkish Cypriots whose enclaves were still occupied by Greek forces. Up to 160,000 Greek-Cypriots went south when the fighting started. Some 50,000 Turkish-Cypriots later (1975) moved north.

Turkey's international reputation suffered as a result of the precipitate move of the Turkish military to extend control to a third of the island. The British Prime Minister regarded the Turkish ultimatum as unreasonable since it was presented without allowing adequate time for study. In Greek eyes the Turkish proposals were submitted in the full awareness that the Greek side could not accept them and reflected the Turkish desire for a military base in Cyprus. The Greek side has gone some way in their proposals by recognising Turkish `groups' of villages and Turkish administrative `areas'. But they stressed that the constitutional order of Cyprus should retain its bi-communal character based on the co-existence of the Greek and Turkish communities within the framework of a sovereign, independent and integral republic. Essentially the Turkish side's proposals were for geographic consolidation and separation and for a much larger measure of autonomy for that area, or those areas, than the Greek side could envisage.

, the UN Secretary-General, launched a new mission of Good Offices. Starting in Vienna, over the course of the following ten months Clerides and Denktaş held discussed a range of humanitarian issues relating to the events of the previous year. However, attempts to make progress on the substantive issues – such as territory and the nature of the central government – failed to produce any results. After five rounds the talks fell apart in February 1976. In January 1977, the UN managed to organise a meeting in Nicosia between Makarios

and Denktaş

. This led to a major breakthrough. On February 12, the two leaders signed a four point agreement confirming that a future Cyprus settlement would be based on a federation

. The size of the states would be determined by economic viability and land ownership. The central government would be given powers to ensure the unity of the state. Various other issues, such as freedom of movement and freedom of settlement, would be settled through discussion. Just months later, in August 1977, Makarios

died. He was replaced by Spyros Kyprianou

, the foreign minister.

In May 1979, Waldheim visited Cyprus and secured a further ten-point set of proposals 1979 from the two sides. In addition to re-affirming the 1977 High Level Agreement, these also included provisions for the demilitarisation of the island and a commitment to refrain from destabilising activities and actions. Shortly afterwards a new round of discussions began in Nicosia. Again, they were short lived. For a start, the Turkish Cypriots did not want to discuss Varosha, a resort quarter of Famagusta that had been vacated by Greek-Cypriots when it was over-run by Turkish troops. This was a key issue for the Greek Cypriots. Secondly, the two sides failed to agree on the concept of ‘bicommunality’. The Turkish Cypriots believed that the Turkish Cypriot federal state would be exclusively Turkish Cypriot and the Greek Cypriot state would be exclusively Greek Cypriots. The Greek Cypriots believed that the two states should be predominantly, but not exclusively, made up of a particular community.

In May 1983, an effort by Javier Pérez de Cuéllar

In May 1983, an effort by Javier Pérez de Cuéllar

, the then UN Secretary-General, foundered after the United Nations General Assembly

passed a resolution calling for the withdrawal of all occupation forces from Cyprus. The Turkish Cypriots were furious at the resolution. They threatened to declare independence in retaliation. Despite this, in August, Pérez de Cuéllar gave the two sides a set of proposals for consideration that called for a rotating presidency, the establishment of a bicameral assembly along the same lines as previously suggested and 60:40 representation in the central executive. In return for increased representation in the central government, the Turkish Cypriots would surrender 8–13 per cent of the land in their possession. Both Kyprianou and Denktaş accepted the proposals. However, on 15 November 1983, the Turkish Cypriots took advantage of the post-election political instability in Turkey and unilaterally declared independence

. Within days the Security Council passed a resolution, no.541 (13-1 vote: only Pakistan

opposed) making it clear that it would not accept the new state and that the decision disrupted efforts to reach a settlement. Denktaş denied this. In a letter addressed to the Secretary-General informing him of the decision, he insisted that the move guaranteed that any future settlement would be truly federal in nature. Although the ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’ (TRNC) was soon recognised by Turkey

, the rest of the international community condemned the move. The Security Council passed another resolution, no.550 (13-1 vote: again only Pakistan

opposed) condemning the "purported exchange of ambassadors between Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot leadership..."

In September 1984 talks resumed. After three rounds of discussions it was again agreed that Cyprus would become a bizonal, bicommunal, non-aligned federation. The Turkish Cypriots would retain 29 per cent for their federal state and all foreign troops would leave the island. In January 1985, the two leaders met for their first face-to-face talks since the 1979 agreement. However, while the general belief was that the meeting was being held to agree to a final settlement, Kyprianou insisted that it was a chance for further negotiations. The talks collapsed. In the aftermath, the Greek Cypriot leaders came in for heavy criticism, both at home and abroad. After that Denktaş announced that he would not make so many concessions again. Undeterred, in March 1986, de Cuéllar presented the two sides with a Draft Framework Agreement. Again, the plan envisaged the creation of an independent, non-aligned, bi-communal, bi-zonal state in Cyprus. However, the Greek Cypriots were unhappy with the proposals. They argued that the questions of removing Turkish forces from Cyprus was not addressed, nor was the repatriation of the increasing number of Turkish settlers on the island. Moreover, there were no guarantees that the full three freedoms would be respected. Finally, they saw the proposed state structure as being confederal in nature. Further efforts to produce an agreement failed as the two sides remained steadfastly attached to their positions.

and Rauf Denktaş

- agreed to abandon the Draft Framework Agreement and return to the 1977 and 1979 High Level Agreements. But the talks faltered when the Greek Cypriots announced their intention to apply for membership within the European Community (EC), a move strongly opposed by the Turkish Cypriots and Turkey. Nevertheless, in June 1989, de Cuellar presented the two communities with the 'Set of Ideas'. Denktaş quickly rejected them as he not only opposed the provisions, he also argued that the UN Secretary-General had no right to present formal proposals to the two sides. The two sides met again, in New York, in February 1990. However, the talks were again short lived. This time Denktaş demanded that the Greek Cypriots recognise the existence of two peoples in Cyprus and the basic right of the Turkish Cypriots to self-determination.

On 4 July 1990, Cyprus formally applied to join the EC. The Turkish Cypriots and Turkey, which had applied for membership in 1987, were outraged. Denktaş claimed that Cyprus could only join the Community at the same time as Turkey and called off all talks with UN officials. Nevertheless, in September 1990, the EC member states unanimously agreed to refer the Cypriot application to the Commission for formal consideration. In retaliation, Turkey and the TRNC signed a joint declaration abolishing passport controls and introducing a customs union just weeks later. Undeterred, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar

continued his search for a solution throughout 1991. He made no progress. In his last report to the Security Council, presented in October 1991 under United Nations Security Council Resolution 716

, he blamed the failure of the talks on Denktaş, noting the Turkish Cypriot leader's demand that the two communities should have equal sovereignty and a right to secession.

On 3 April 1992, Boutros Boutros-Ghali

, the new UN Secretary-General, presented the Security Council with the outline plan for the creation of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation that would prohibit any form of partition, secession or union with another state. While the Greek Cypriots accepted the Set of Ideas as a basis for negotiation, Denktaş again criticised the UN Secretary-General for exceeding his authority. When he did eventually return to the table, the Turkish Cypriot leader complained that the proposals failed to recognise his community. In November, Ghali brought the talks to a halt. He now decided to take a different approach and tried to encourage the two sides to show goodwill by accepting eight confidence building measures (CBMs). These included reducing military forces on the island, transferring Varosha to direct UN control, reducing restrictions on contacts between the two sides, undertaking an island-wide census and conducting feasibility studies regarding a solution. The Security Council endorsed the approach.

On 24 May 1993, the Secretary-General formally presented the two sides with his CBMs. Denktaş, while accepting some of the proposals, was not prepared to agree to the package as a whole. Meanwhile, on June 30, the European Commission returned its opinion on the Cypriot application for membership. While the decision provided a ringing endorsement of the case for Cypriot membership, it refrained from opening the way for immediate negotiations. The Commission stated that it felt that the issue should be reconsidered in January 1995, taking into account "the positions adopted by each party in the talks". A few months later, in December 1993, Glafcos Clerides proposed the demilitarisation of Cyprus. Denktaş dismissed the idea, but the next month he announced that he would be willing to accept the CBMs in principle. Proximity talks started soon afterwards. In March 1994, the UN presented the two sides with a draft document outlining the proposed measures in greater detail. Clerides said that he would be willing to accept the document if Denktaş did, but the Turkish Cypriot leader refused on the grounds that it would upset the balance of forces on the island. Once again, Ghali had little choice but to pin the blame for another breakdown of talks on the Turkish Cypriot side. Denktas would be willing to accept mutually agreed changes. But Clerides refused to negotiate any further changes to the March proposals. Further proposals put forward by the Secretary-General in an attempt to break the deadlock were rejected by both sides.

European Council

, held on 24–25 June 1994, the EU officially confirmed that Cyprus would be included in the Union's next phase of enlargement. Two weeks later, on July 5, the European Court of Justice

imposed restrictions on the export of goods from Northern Cyprus into the European Union

. Soon afterwards, in December, relations between the EU and Turkey were further damaged when Greece blocked the final implementation of a customs union. As a result, talks remained completely blocked throughout 1995 and 1996. The situation took another turn for the worse at the start of 1997 when the Greek Cypriots announced that they intended to purchase the Russian-made S-300 anti-aircraft missile system. Soon afterwards, Turkey announced that it would match any military build-up. However, Turkey was now starting to come under increasing pressure from several sides. In December 1996, the European Court of Human Rights

(ECHR) delivered a landmark ruling that declared that Turkey was an occupying power in Cyprus. The case - Loizidou vs Turkey

- centred on Titina Loizidou, a refugee from Kyrenia

, who was judged to have been unlawfully denied the control of her property by Turkey. In addition to being a major political embarrassment for Ankara

, the case also had severe financial implications as the Court later ruled that Turkey should pay Mrs Loizidou US$825,000 in compensation for the loss of use of her property. Ankara rejected the ruling as politically motivated.

After twenty years of talks, a settlement seemed as far off as ever. However, the basic parameters of a settlement were by now internationally agreed. Cyprus would be a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation

. A solution would also be expected to address the following issues:

to open up accession negotiations with the Republic of Cyprus created a new catalyst for a settlement. Among those who supported the move, the argument was made that Turkey could not have a veto on Cypriot accession and that the negotiations would encourage all sides to be more moderate. However, opponents of the move argued that the decision would remove the incentive of the Greek Cypriots to reach a settlement. They would instead wait until they became a member and then use this strength to push for a settlement on their terms. In response to the decision, Rauf Denktaş announced that he would no longer accept federation as a basis for a settlement. In the future he would only be prepared to negotiate on the basis of a confederal solution. In December 1999 tensions between Turkey and the European Union eased somewhat after the EU decided to declare Turkey a candidate for EU membership, a decision taken at the Helsinki European Council. At the same time a new round of talks started in New York. These were short lived. By the following summer they had broken down. Tensions started to rise again as a showdown between Turkey and the European Union loomed over the island's accession.

Perhaps realising the gravity of the situation, and in a move that took observers by surprise, Rauf Denktaş

wrote to Glafcos Clerides on 8 November 2001 to propose a face-to-face meeting. The offer was accepted. Following several informal meetings between the two men in November and December 2001 a new peace process started under UN auspices on 14 January 2002. At the outset the stated aim of the two leaders was to try to reach an agreement by the start of June that year. However, the talks soon became deadlocked. In an attempt to break the impasse, Kofi Annan

, the UN Secretary-General visited the island in May that year

. Despite this no deal was reached. After a summer break Annan met with the two leaders again that autumn, first in Paris and then in New York. As a result of the continued failure to reach an agreement, the Security Council agreed that the Secretary-General should present the two sides with a blueprint settlement. This would form the basis of further negotiations. The original version of the UN peace plan was presented to the two sides by Annan on 11 November 2002. A little under a month later, and following modifications submitted by the two sides, it was revised (Annan II). It was hoped that this plan would be agreed by the two sides on the margins of the European Council, which was held in Copenhagen

on December 13. However, Rauf Denktaş, who was recuperating from major heart surgery, declined to attend. The EU therefore decided to confirm that Cyprus would join the EU on 1 May 2004, along with Malta

and eight other states from Central

and Eastern Europe

.

Although it had been expected that talks would be unable to continue, discussions resumed in early January 2003. Thereafter, a further revision (Annan III) took place in February 2003, when Annan made a second visit to the island. During his stay he also called on the two sides to meet with him again the following month in The Hague

, where he would expect their answer on whether they were prepared to put the plan to a referendum. While the Greek Cypriot side, which was now led by Tassos Papadopoulos

, agreed to do so, albeit reluctantly, Rauf Denktaş

refused to allow a popular vote. The peace talks collapsed. A month later, on 16 April 2003, Cyprus formally signed the EU Treaty of Accession

at a ceremony in Athens

.

Throughout the rest of the year there was no effort to restart talks. Instead, attention turned to the Turkish Cypriot elections

, which were widely expected to see a victory by moderate pro-solution parties. In the end, the assembly was evenly split. A coalition administration was formed that brought together the pro-solution CTP

and the Democrat Party

, which had traditionally taken the line adopted by Rauf Denktaş. This opened the way for Turkey to press for new discussions. After a meeting between Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

and Kofi Annan

in Switzerland

, the leaders of the two sides were called to New York

. There they agreed to start a new negotiation process based on two phases: phase one, which would just involve the Greek and Turkish Cypriots, being held on the island and phase two, which would also include Greece and Turkey, being held elsewhere. After a month of negotiations in Cyprus, the discussions duly moved to Burgenstock, Switzerland. The Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş rejected the plan outright and refused to attend these talks. Instead, his son Serdar Denktaş

and Mehmet Ali Talat

attended in his place. There a fourth version of the plan was presented. This was short-lived. After final adjustments, a fifth and final version of the Plan was presented to the two sides on 31 March 2004.

composed of two component states. The northern Turkish Cypriot constituent state would encompass about 28.5% of the island, the southern Greek Cypriot constituent state would be made up of the remaining 71.5%. Each part would have had its own parliament. There would also be a bicameral parliament

on the federal level. In the Chamber of Deputies

, the Turkish Cypriots would have 25% of the seats. (While no accurate figures are currently available, the split between the two communities at independence in 1960 was approximately 80:20 in favour of the Greek Cypriots.) The Senate

would consist of equal parts of members of each ethnic group. Executive power would be vested in a presidential council. The chairmanship of this council would rotate between the communities. Each community would also have the right to veto all legislation.

One of the most controversial elements of the plan concerned property. During Turkey's military intervention/invasion in 1974, many Greek Cypriots (who owned 90% of the land and property in the north) were forced to abandon their homes. (A large number of Turkish Cypriots also left their homes.) Since then, the question of restitution of their property has been a central demand of the Greek Cypriot side. However, the Turkish Cypriots argue that the complete return of all Greek Cypriot properties to their original owners would be incompatible with the functioning of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federal settlement. To this extent, they have argued compensation should be offered. The Annan Plan attempted to bridge this divide. In certain areas, such as Morphou (Güzelyurt) and Famagusta

(Gazimağusa), which would be returned to Greek Cypriot control, Greek Cypriot refugees would have received back all of their property according to a phased timetable. In other areas, such as Kyrenia

(Girne) and the Karpass Peninsula

, which would remain under Turkish Cypriot control, they would be given back a proportion of their land (usually one third assuming that it had not been extensively developed) and would receive compensation for the rest. All land and property (that was not used for worship) belonging to businesses and institutions, including the Church the largest property owner on the island, would have been expropriated. While many Greek Cypriots found these provisions unacceptable in themselves, many others resented the fact that the Plan envisaged all compensation claims by a particular community to be met by their own side. This was seen as unfair as Turkey would not be required to contribute any funds towards the compensation.

Apart from the property issue, there were many other parts of the plan that sparked controversy. For example, the agreement envisaged the gradual reduction in the number of Greek and Turkish troops on the island. After six years, the number of soldiers from each country would be limited to 6,000. This would fall to 600 after 19 years. Thereafter, the aim would be to try to achieve full demilitarization, a process that many hoped would be made possible by Turkish accession to the European Union. The agreement also kept in place the Treaty of Guarantee - an integral part of the 1960 constitution that gave Britain, Greece and Turkey a right to intervene militarily in the island's affairs. Many Greek Cypriots were concerned that the continuation of the right of intervention would give Turkey too large a say in the future of the island. However, most Turkish Cypriots felt that a continued Turkish military presence was necessary to ensure their security. Another element of the plan the Greek Cypriots objected to was that it allowed many Turkish citizens who had been brought to the island to remain. (The exact number of these Turkish 'settlers' is highly disputed. Some argue that the figure is as high as 150,000 or as low as 40,000. They are seen as settlers illegally brought to the island in contravention of international law. However, while many accepted Greek Cypriot concerns on this matter, there was a widespread feeling that it would be unrealistic to forcibly remove every one of the these settlers, especially as many of them had been born and raised on the island.

, it soon became clear that the Turkish Cypriots would vote in favour of the agreement. Among Greek Cypriots opinion was heavily weighted against the plan. Tassos Papadopoulos

, the president of Cyprus, in a speech delivered on 7 April called on Greek Cypriots to reject the plan. His position was supported by the centrist Diko party and the socialists of EDEK as well as other smaller parties. His major coalition partner AKEL, one of the largest parties on the island, chose to reject the plan bowing to the wishes of the majority of the party base. Support for the plan was voiced by Democratic Rally

(DISY) leadership, the main right-wing party, despite opposition to the plan from the majority of party followers, and the United Democrats

, a small centre-left party led by George Vasiliou

, a former president. Glafcos Clerides, now retired from politics, also supported the plan. Prominent members of DISY who did not support the Annan plan split from the party and openly campaigned against it. The Greek Cypriot Church also opposed the plan in line with the views of the majority of public opinion.

The United Kingdom (a Guarantor Power) and the United States came out in favour of the plan. Turkey signaled its support for the plan. The Greek Government decided to remain neutral. However, Russia was troubled by an attempt by Britain and the US to introduce a resolution in the UN Security Council supporting the plan and used its veto to block the move. This was done as they felt that Britain and the US were trying to put unfair pressure on the Greek Cypriots.

In the 24 April referendum

the Turkish Cypriots endorsed the plan by a margin of almost two to one. However, the Greek Cypriots resoundingly voted against the plan, by a margin of about three to one.

Referendum results:

, Cyprus joined the European Union

. Under the terms of accession the whole island is considered to be a member of the European Union. However, the terms of the acquis communautaire

, the EU's body of laws, have been suspended in the north.

Despite initial hopes that a new process to modify the rejected plan would start by autumn, most of the rest of 2004 was taken up with discussions over a proposal by the European Union to open up direct trade with the Turkish Cypriots and provide €

259,000,000 in funds to help them upgrade their infrastructure. This has provoked considerable debate. The Republic of Cyprus has argued that there can be no direct trade via ports and airports in Northern Cyprus as these are unrecognised. Instead, it has offered to allow Turkish Cypriots to use Greek Cypriot facilities, which are internationally recognized. This has been rejected by the Turkish Cypriots. At the same time, attention turned to the question of the start of Turkey's future membership of the European Union. At a European Council

held on 17 December 2004, and despite earlier Greek Cypriot threats to impose a veto, Turkey was granted a start date for formal membership talks on condition that it signed a protocol extending the customs union to the new entrants to the EU, including Cyprus. Assuming this is done, formal membership talks would begin on 3 October 2005.

Following the defeat of the UN plan in the referendum there has been no attempt to restart negotiations between the two sides. While both sides have reaffirmed their commitment to continuing efforts to reach an agreement, the UN Secretary-General has not been willing to restart the process until he can be sure that any new negotiations will lead to a comprehensive settlement based on the plan he put forward in 2004. To this end, he has asked the Greek Cypriots to present a written list of the changes they would like to see made to the agreement. This was rejected by President Tassos Papadopoulos

on the grounds that no side should be expected to present their demands in advance of negotiations. However, it appears as though the Greek Cypriots would be prepared to present their concerns orally. Another Greek Cypriot concern centres on the procedural process for new talks. Mr. Papadopoulos said that he will not accept arbitration or timetables for discussions. The UN fears that this would lead to another open-ended process that could drag on indefinitely.

caused a controversy, when winner Felipe Massa

received the trophy from Mehmet Ali Talat

, who was referred to as the "President of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus." The government of the Republic of Cyprus filed an official complaint with the FIA

. After investigating the incident, the FIA fined the organizers of the Grand Prix $5 million on 19 September 2006. The Turkish Motorsports Federation (TOSFED) and the organizers of the Turkish Grand Prix

(MSO) agreed to pay half the fined sum pending an appeal to be heard by the FIA International Court of Appeal on November 7, 2006. TOSFED insisted the move was not planned and that Mehmet Ali Talat did fit FIA's criteria for podium presentations as a figure of world standing. Keen to repair their impartiality in international politics, FIA stood their ground forcing the appeal to be withdrawn.

, Papadopoulos was defeated by AKEL

candidate Dimitris Christofias

, who pledged to restart talks on reunification immediately. Speaking on the election result, Mehmet Ali Talat

stated that "this forthcoming period will be a period during which the Cyprus problem can be solved within a reasonable space of time – despite all difficulties – provided that there is will". Christofias held his first meeting as president with the Turkish Cypriot leader on 21 March 2008 in the UN buffer zone

in Nicosia. At the meeting, the two leaders agreed to launch a new round of "substantive" talks on reunification, and to reopen Ledra Street

, which has been cut in two since the intercommunal violence

of the 1960s and has come to symbolize the island's division. On 3 April 2008, after barriers had been removed, the Ledra Street

crossing was reopened in the presence of Greek and Turkish Cypriot officials.

At a meeting on 1 July 2008, the two leaders agreed in principle on the concepts of a single citizenship and a single sovereignty, and decided to start direct reunification talks very soon; on the same date, former Australia

n foreign minister Alexander Downer

was appointed as the new UN envoy for Cyprus. Christofias and Talat agreed to meet again on 25 July 2008 for a final review of the preparatory work before the actual negotiations would start. Christofias was expected to propose a rotating presidency for the united Cypriot state. Talat stated he expected they would set a date to start the talks in September, and reiterated that he would not agree to abolishing the guarantor roles of Turkey and Greece.

After the conclusion of negotiations, a reunification plan would be put to referendums in both communities.

In December 2008, the Athenian

socialist daily newspaper To Vima

described a "crisis" in relations between Christofias and Talat, with the Turkish Cypriots beginning to speak openly of a loose "confederation", an idea strongly opposed by Nicosia. Tensions were further exacerbated by Turkey's harassment of Cypriot vessels engaged in oil exploration in the island's Exclusive Economic Zone

, and by the Turkish Cypriot leadership's alignment with Ankara's claim that Cyprus has no continental shelf

.

On 29 April 2009, Talat stated that if the Court of Appeal of England and Wales

(that will put the last point in the Orams' case

) makes a decision just like in the same spirit with the decision of European Court of Justice

(ECJ) then the Negotiation Process in Cyprus will be damaged in such a way that it will never be repaired once more. The European Commission warned the Republic of Cyprus not to turn Orams' case

legal fight to keep their holiday home into a political battle over the divided island.

On 31 January 2010, United Nations

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

arrived in Cyprus to accelerate talks aimed at reuniting the country.

The election

of nationalist Derviş Eroğlu

of the National Unity Party as president in Northern Cyprus on April 18 is expected to complicate reunification negotiations. Talks were resumed after the elections in late May, however, and Eroǧlu stated on 27 May 2010 he was now also in favour of a federal state, a change from his previous positions.

In early June 2010, talks reached an impasse and UN Special Advisor Alexander Downer

called on the two leaders to decide whether they wanted a solution or not.

On 18 November 2010, 1st tripartite meeting (Ban, Christofias, Eroglu) occurred in New York, US without any agreement over the main issues.

On 26 January 2011, 2nd tripartite meeting (Ban, Christofias, Eroglu) occurred in Geneva, Switzerland without any agreement over the main issues.

On March 2011, United Nations

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

reported, "The negotiations cannot be an open-ended process, nor can we afford interminable talks for the sake of talks".

On 18 March 2011, Greek Cypriots

and Turkish Cypriots

realized 100th negotiation since April 2008 without any agreement over the main issues.

By mid-2011, there was a renewed push for an end to negotiations by the end of 2011 in order to have a united Cyprus take over the EU presidency on 1 July 2012.

On 07 July 2011, the 3rd tripartite meeting (Ban, Christofias, Eroglu) occurred in Geneva, Switzerland without any agreement over the main issues.

On 30-31 October 2011, the 4th tripartite meeting (Ban, Christofias, Eroglu) occurred in New York, US without any agreement over the main issues. Ban said that the talks are coming to an end.

An international panel of legal experts proposed the “creation of a Constitutional Convention under European Union auspices and on the basis of the 1960 Cyprus Constitution to bring together the parties directly concerned in order to reach a settlement in conformity with the Fundamental Principles.”

is a pending class action

suit by Greek Cypriots

and others against the TRNC Representative Offices in the United States and HSBC Bank USA. The TRNC Representative Offices are a commercial entity because the United States does not formally recognize the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

. The staff of the Representative Offices do not have diplomatic visas and only operate within the United States

using business visas. Tsimpedes Law in Washington DC is suing for "the denial of access to and enjoyment of land and property held in the north". The lawsuit, originally initiated by Cypriots displaced during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, has been joined by non-Cypriots who paid for but have never been given legal title to properties that they have purchased.

Lambros Philippou (2011) The Dialectic of the Cypriot Reason (Entipis, Nicosia)

Documentaries

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, over the Turkish occupied northern part of Cyprus.

Initially, with the annexation of the island by the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

, the "Cyprus dispute" was identified as the conflict between the people of Cyprus and the British Crown

The Crown

The Crown is a corporation sole that in the Commonwealth realms and any provincial or state sub-divisions thereof represents the legal embodiment of governance, whether executive, legislative, or judicial...

regarding the Cypriots' demand for self determination. The dispute however was finally shifted from a colonial dispute to an ethnic dispute between the Turkish and the Greek islanders. The international complications of the dispute stretch far beyond the boundaries of the island of Cyprus itself and involve the guarantor powers (Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, and the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

alike), along with the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and the European Union

European Union

The European Union is an economic and political union of 27 independent member states which are located primarily in Europe. The EU traces its origins from the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community , formed by six countries in 1958...

.

With the invasion

Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus, launched on 20 July 1974, was a Turkish military invasion in response to a Greek military junta backed coup in Cyprus...

of 1974 (condemned by UN Security Council Resolutions as legally invalid), Turkey occupied the northern part of the internationally recognised Republic of Cyprus, and later upon those territories the Turkish Cypriot

Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots are the ethnic Turks and members of the Turkish-speaking ethnolinguistic community of the Eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus. The term is used to refer explicitly to the indigenous Turkish Cypriots, whose Ottoman Turkish forbears colonised the island in 1571...

community unilaterally declared independence forming the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a sovereign entity that lacks international recognition-with the exception of Turkey with which TRNC enjoys full diplomatic relations.

After the two communities and the guarantor countries have committed themselves in finding a peaceful solution over the dispute, the United Nations have since created and maintained a buffer zone (the "Green Line

United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus

The United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus runs for more than along what is known as the Green Line and has an area of . The zone partitions the island of Cyprus into a southern area effectively controlled by the government of the Republic of Cyprus , and the northern area...

") to avoid any further intercommunal tensions and hostilities. This zone separates the Greek Cypriot-controlled south from the Turkish Cypriot-controlled north.

Historical background prior to 1960

The island of Cyprus was first inhabited in 9000 BC with the arrival of farming societies who built round houses with floors of terazzo. Cities were first built during the Bronze Age and the inhabitants had their own Eteocypriot language until around the 4th century BC. The island was part of the Hittite Empire as part of the Ugarit Kingdom during the late Bronze Age until the arrival of two waves of Greek settlement.Cyprus experienced an uninterrupted Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

presence on the island dating from the arrival of Mycenaeans

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece was a cultural period of Bronze Age Greece taking its name from the archaeological site of Mycenae in northeastern Argolis, in the Peloponnese of southern Greece. Athens, Pylos, Thebes, and Tiryns are also important Mycenaean sites...

around 1100 BC, when the burials began to take the form of long dromos. The Greek population of Cyprus survived through multiple conquerors, including Egyptian and Persian rule. In the 4th century BC, Cyprus was conquered by Alexander the Great and then ruled by the Ptolemaic Egypt

Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom in and around Egypt began following Alexander the Great's conquest in 332 BC and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest in 30 BC. It was founded when Ptolemy I Soter declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt, creating a powerful Hellenistic state stretching from...

until 58 BC, when it was incorporated into the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. After an interval of Islam Khalifate (643-966), the island returned to Roman rule until the 12th century. After an occupation by the Knights Templar

Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon , commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders...

and the rule of Isaac Komnenos

Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus

Isaac Komnenos or Comnenus , was the ruler of Cyprus from 1184 to 1191, before Richard I's conquest during the Third Crusade.-Family:He was a minor member of the Komnenos family. He was son of an unnamed Doukas Kamateros and Irene Komnene...

, the island in 1192 came under the rule of the Lusignan family, who established the Kingdom of Cyprus

Kingdom of Cyprus

The Kingdom of Cyprus was a Crusader kingdom on the island of Cyprus in the high and late Middle Ages, between 1192 and 1489. It was ruled by the French House of Lusignan.-History:...

. In February 1489 it was seized by the Republic of Venice

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

. Between September 1570 and August 1571 it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, starting three centuries of Turkish rule over Cyprus.

Starting in the early nineteenth century, ethnic Greeks of the island sought to bring about an end to almost 300 years of Ottoman rule and unite Cyprus with Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

. The United Kingdom took administrative control of the island in 1878, to prevent Ottoman positions from falling under Russian control following the Cyprus Convention

Cyprus Convention

The Cyprus Convention of 4 June, 1878 was a secret agreement reached between the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire which granted control of Cyprus to Great Britain in exchange for their support of the Ottomans during the Congress of Berlin...

, which lead to the call for union (enosis

Enosis

Enosis refers to the movement of the Greek-Cypriot population to incorporate the island of Cyprus into Greece.Similar movements had previously developed in other regions with ethnic Greek majorities such as the Ionian Islands, Crete and the Dodecanese. These regions were eventually incorporated...

) to grow louder. Under the terms of the agreement reached between Britain and the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, the island remained an Ottoman territory.

The Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

Greek-speaking inhabitants of the island welcomed the arrival of the British as a chance to voice their demands for union with Greece: enosis.

When the Ottoman Empire entered World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

on the side of the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

, Britain renounced the agreement and all Turkish claims over Cyprus and declared the island a British colony. In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Constantine I of Greece

Constantine I of Greece

Constantine I was King of Greece from 1913 to 1917 and from 1920 to 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Army during the unsuccessful Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and led the Greek forces during the successful Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, in which Greece won Thessaloniki and doubled in...

on condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British, which he declined.

1918 to 1955

Under British rule in the early 20th century, Cyprus escaped the conflicts and atrocities that went on elsewhere between Greeks and Turks; notably during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and the 1923 Population exchange between Greece and TurkeyPopulation exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey was based upon religious identity, and involved the Greek Orthodox citizens of Turkey and the Muslim citizens of Greece...

. Turkish Cypriots consistently opposed the idea of union with Greece.

In 1925 Britain declared Cyprus to be a Crown Colony

Crown colony

A Crown colony, also known in the 17th century as royal colony, was a type of colonial administration of the English and later British Empire....

. In the years that followed, the determination for enosis continued. In 1931 this led to open revolution. A riot resulted in the death of six civilians, injuries to others and the burning of the British Government House in Nicosia

Nicosia

Nicosia from , known locally as Lefkosia , is the capital and largest city in Cyprus, as well as its main business center. Nicosia is the only divided capital in the world, with the southern and the northern portions divided by a Green Line...

. In the months that followed, about 2,000 people were convicted of crimes in connection with the struggle for union with Greece. Britain reacted by imposing harsh restrictions. Military reinforcements were dispatched to the island and the constitution suspended. A special "epicourical" (reserve) police force was formed consisting of only Turkish Cypriots, press restrictions instituted and political parties banned. Two bishops and eight other prominent citizens directly implicated in the conflict were exiled. Municipal elections were suspended, and until 1943 all municipal officials were appointed by the government. The governor was to be assisted by an Executive Council, and two years later an Advisory Council was established; both councils consisted only of appointees and were restricted to advising on domestic matters only. In addition, the flying of Greek

Flag of Greece

The flag of Greece , officially recognized by Greece as one of its national symbols, is based on nine equal horizontal stripes of blue alternating with white...

or Turkish flags

Flag of Turkey

The flag of Turkey is a red flag with a white crescent moon and a star in its centre. The flag is called Ayyıldız or Albayrak . The Turkish flag is referred to as Alsancak in the Turkish National Anthem....

or the public display of portraits of Greek or Turkish heroes was forbidden.

The struggle for enosis was put on hold during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. In 1946, the British government announced plans to invite Cypriots to form a Consultative Assembly to discuss a new constitution. The British also allowed the return of the 1931 exiles. Instead of reacting positively, as expected by the British, the Greek Cypriot military hierarchy reacted angrily because there had been no mention of enosis. The Cypriot Orthodox Church

Cypriot Orthodox Church

The Church of Cyprus is an autocephalous Greek church within the communion of Orthodox Christianity. It is one of the oldest Eastern Orthodox autocephalous churches, achieving independence from the Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East in 431...

had expressed its disapproval, and Greek Cypriots declined the British invitation, stating that enosis was their sole political aim. The efforts by Greeks to bring about enosis now intensified, helped by active support of the Church of Cyprus, which was the main political voice of the Greek Cypriots at the time. However, it was not the only organization claiming to speak for the Greek Cypriots. The Church's main opposition came from the Cypriot Communist Party (officially the Progressive Party of the Working People; Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού; or AKEL), which also wholeheartedly supported the Greek national goal of enosis. However the British military forces and Colonial administration in Cyprus did not see the pro-Soviet communist party as a viable partner.