Counterculture of the 1960s

Encyclopedia

Counterculture

Counterculture is a sociological term used to describe the values and norms of behavior of a cultural group, or subculture, that run counter to those of the social mainstream of the day, the cultural equivalent of political opposition. Counterculture can also be described as a group whose behavior...

of the 1960s

1960s

The 1960s was the decade that started on January 1, 1960, and ended on December 31, 1969. It was the seventh decade of the 20th century.The 1960s term also refers to an era more often called The Sixties, denoting the complex of inter-related cultural and political trends across the globe...

refers to a cultural movement that mainly developed in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and spread throughout much of the western world between 1960 and 1973. The movement gained momentum during the U.S. government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

's extensive military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

intervention in Vietnam

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

. As the 1960s progressed, widespread tensions developed in American society

Culture of the United States

The Culture of the United States is a Western culture originally influenced by European cultures. It has been developing since long before the United States became a country with its own unique social and cultural characteristics such as dialect, music, arts, social habits, cuisine, and folklore...

that tended to flow along generational lines regarding the war in Vietnam

Vietnam

Vietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

, race relations, sexual

Human sexuality

Human sexuality is the awareness of gender differences, and the capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Human sexuality can also be described as the way someone is sexually attracted to another person whether it is to opposite sexes , to the same sex , to either sexes , or not being...

mores

Mores

Mores, in sociology, are any given society's particular norms, virtues, or values. The word mores is a plurale tantum term borrowed from Latin, which has been used in the English language since the 1890s....

, women's rights

Women's rights

Women's rights are entitlements and freedoms claimed for women and girls of all ages in many societies.In some places these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behaviour, whereas in others they may be ignored or suppressed...

, traditional modes of authority

Authority

The word Authority is derived mainly from the Latin word auctoritas, meaning invention, advice, opinion, influence, or command. In English, the word 'authority' can be used to mean power given by the state or by academic knowledge of an area .-Authority in Philosophy:In...

, experimentation with psychoactive

Psychoactive drug

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical, or psychotropic is a chemical substance that crosses the blood–brain barrier and acts primarily upon the central nervous system where it affects brain function, resulting in changes in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, and behavior...

drugs, and differing interpretations of the American Dream

American Dream

The American Dream is a national ethos of the United States in which freedom includes a promise of the possibility of prosperity and success. In the definition of the American Dream by James Truslow Adams in 1931, "life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each...

. New cultural forms emerged, including the pop music of the British band The Beatles

The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, active throughout the 1960s and one of the most commercially successful and critically acclaimed acts in the history of popular music. Formed in Liverpool, by 1962 the group consisted of John Lennon , Paul McCartney , George Harrison and Ringo Starr...

and the concurrent rise of hippie

Hippie

The hippie subculture was originally a youth movement that arose in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to other countries around the world. The etymology of the term 'hippie' is from hipster, and was initially used to describe beatniks who had moved into San Francisco's...

culture, which led to the rapid evolution of a youth subculture

Youth subculture

A youth subculture is a youth-based subculture with distinct styles, behaviors, and interests. Youth subcultures offer participants an identity outside of that ascribed by social institutions such as family, work, home and school...

that emphasized change and experimentation. In addition to the Beatles, many songwriters, singers and musical groups from the United Kingdom and America came to impact the counterculture movement.

Social anthropologist

Cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans, collecting data about the impact of global economic and political processes on local cultural realities. Anthropologists use a variety of methods, including participant observation,...

Jentri Anders observed that a number of freedoms were endorsed within a countercultural community in which she lived and studied: "freedom to explore one’s potential, freedom to create one’s Self, freedom of personal expression, freedom from scheduling, freedom from rigidly defined roles and hierarchical statuses...". Additionally, Anders believed some in the counterculture wished to modify children's education so that it didn't discourage, but rather encouraged, "aesthetic sense, love of nature, passion for music, desire for reflection, or strongly marked independence."

Background

The Cold WarCold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

(between communist states and capitalist states) involved espionage

Espionage

Espionage or spying involves an individual obtaining information that is considered secret or confidential without the permission of the holder of the information. Espionage is inherently clandestine, lest the legitimate holder of the information change plans or take other countermeasures once it...

on a global scale, along with political and military interference in the internal affairs of lesser nations (see Timeline of events in the Cold War

Timeline of events in the Cold War

-1945:*February 4: The Yalta Conference occurs, deciding the post-war status of Germany. The Allies of World War II divide Germany into four occupation zones. The Allied nations agree that free elections are to be held in all countries occupied by Nazi Germany...

). Poor outcomes from some of these activities set the stage for disillusionment with, and distrust of, post-war governments. Examples included harsh Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

responses to popular anti-communist uprisings, such as the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and Czechoslovakia's Prague Spring

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia during the era of its domination by the Soviet Union after World War II...

in 1968, as well as the botched U.S. Bay of Pigs Invasion

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion was an unsuccessful action by a CIA-trained force of Cuban exiles to invade southern Cuba, with support and encouragement from the US government, in an attempt to overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The invasion was launched in April 1961, less than three months...

of Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

in 1961. In the U.S., President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

's initial deception over the nature of the 1960 U-2 incident resulted in the government being caught in a blatant lie at the highest levels, and set the stage for a growing distrust of authority among many who came of age during the period.

The Partial Test Ban Treaty

Partial Test Ban Treaty

The treaty banning nuclear weapon tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and under water, often abbreviated as the Partial Test Ban Treaty , Limited Test Ban Treaty , or Nuclear Test Ban Treaty is a treaty prohibiting all test detonations of nuclear weapons...

divided the establishment within the U.S along political and military lines.

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, South-East Asia, South East Asia or Southeastern Asia is a subregion of Asia, consisting of the countries that are geographically south of China, east of India, west of New Guinea and north of Australia. The region lies on the intersection of geological plates, with heavy seismic...

(SEATO), especially in Vietnam

Vietnam

Vietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

, and debate as to how other communist insurgencies should be handled, also created dissent within the establishment.

The Cuban missile crisis

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a confrontation among the Soviet Union, Cuba and the United States in October 1962, during the Cold War...

of October 1962, where the world came closer than at any other point to a nuclear war, caused many people to start questioning whether traditional ways of doing things, were actually working to make the world a better place or instead a worse one.

The assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

in 1963, and doubts as to the validity of the official government findings regarding this event, led to further diminished trust in government, especially among young people (see also: Warren Commission

Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established on November 27, 1963, by Lyndon B. Johnson to investigate the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963...

).

Several factors distinguished the counterculture of the 1960s from the authority-opposition movements of previous eras.

The post-war "baby boom

Baby boom

A baby boom is any period marked by a greatly increased birth rate. This demographic phenomenon is usually ascribed within certain geographical bounds and when the number of annual births exceeds 2 per 100 women...

" constituted an unprecedented number of young, affluent, and potentially disaffected people as prospective participants in a rethinking of the direction of American society. Widespread use of psychoactive drugs contributed to this reevaluation, and a confluence of events and issues served as an intellectual catalyst for change.

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

al civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

illegalities, especially regarding general racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

, the lack of voting rights among Southern blacks, and the existing segregation in the purchasing of homes or rental housing in the North.

On college and university campuses, student activists fought for the right to exercise their basic Constitutional rights, especially freedom of speech

Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship. The term freedom of expression is sometimes used synonymously, but includes any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used...

and freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue and defend common interests...

.

Many counterculture activists became newly aware of the ongoing plight of the poor, and community organizers fought for the funding of anti-poverty programs, particularly within inner city

Inner city

The inner city is the central area of a major city or metropolis. In the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland, the term is often applied to the lower-income residential districts in the city centre and nearby areas...

areas in the United States.

Environmentalism

Environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology and social movement regarding concerns for environmental conservation and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seeks to incorporate the concerns of non-human elements...

grew from a greater understanding of the ongoing damage caused by industrialization, resultant pollution

Pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into a natural environment that causes instability, disorder, harm or discomfort to the ecosystem i.e. physical systems or living organisms. Pollution can take the form of chemical substances or energy, such as noise, heat or light...

, and the misguided use of chemicals such as pesticides in well-meaning efforts to improve the quality of life. Authors such as Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson

Rachel Louise Carson was an American marine biologist and conservationist whose writings are credited with advancing the global environmental movement....

played key roles in developing a new awareness among the world's population of the fragility of planet earth

Gaia hypothesis

The Gaia hypothesis, also known as Gaia theory or Gaia principle, proposes that all organisms and their inorganic surroundings on Earth are closely integrated to form a single and self-regulating complex system, maintaining the conditions for life on the planet.The scientific investigation of the...

, despite resistance from elements of the establishment in many countries

The need to address minority rights of women, gays, the handicapped, and many other neglected constituencies within the larger population came to the forefront as an increasing number of primarily younger people broke free from the constraints of 1950s orthodoxy in a desire to create a more inclusive and tolerant social landscape.

The availability of new and more effective forms of birth control

Birth control

Birth control is an umbrella term for several techniques and methods used to prevent fertilization or to interrupt pregnancy at various stages. Birth control techniques and methods include contraception , contragestion and abortion...

was a key underpinning of the sexual revolution

Sexual revolution

The sexual revolution was a social movement that challenged traditional codes of behavior related to sexuality and interpersonal relationships throughout the Western world from the 1960s into the 1980s...

. The notion of “recreational sex” without the threat of unwanted pregnancy radically changed the social dynamic and permitted both women and men much greater freedom in the selection of sexual lifestyles outside the confines of traditional marriage. With this change in attitude, by the 1990s the ratio of children born out of wedlock rose from 5% to 25% for Whites and from 25% to 66% for African-Americans.

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the role of television

Television

Television is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

as a source of entertainment and information, as well as the attendant massive expansion of consumerism

Consumerism

Consumerism is a social and economic order that is based on the systematic creation and fostering of a desire to purchase goods and services in ever greater amounts. The term is often associated with criticisms of consumption starting with Thorstein Veblen...

afforded by post-war affluence and encouraged by TV advertising

Advertising

Advertising is a form of communication used to persuade an audience to take some action with respect to products, ideas, or services. Most commonly, the desired result is to drive consumer behavior with respect to a commercial offering, although political and ideological advertising is also common...

, were key components in youthful disillusionment and the formulation of new social behaviours. In America, near-real-time TV news coverage of the civil rights era's Birmingham Campaign

Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign was a strategic movement organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to bring attention to the unequal treatment that black Americans endured in Birmingham, Alabama...

, the "Bloody Sunday" event of the Selma to Montgomery marches

Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three marches in 1965 that marked the political and emotional peak of the American civil rights movement. They grew out of the voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama, launched by local African-Americans who formed the Dallas County Voters League...

, and several years of news-footage of the Vietnam War brought bloody confrontations and conflicts into the living rooms for the first time.

The breakdown of enforcement of the American Hays Code concerning censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

in motion picture production, the use of new forms of artistic expression in European and Asian cinema, and the advent of modern production values heralded a new era of European, art-house, pornographic, and American mainstream film production, distribution, and exhibition. This resulted in an almost complete reformation of the western film industry. Likewise, dozens of new film makers across many genres brought previously prohibited subject matter to neighborhood theaters for the first time, even as Hollywood film studios continued to be considered as a part of the establishment by some elements of the counterculture.

Previously disregarded FM radio became a focal point for both music and news for the counterculture generation.

Commune

Commune

Commune may refer to:In society:* Commune, a human community in which resources are shared* Commune , a township or municipality* One of the Communes of France* An Italian Comune...

s, collective

Collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together on a specific project to achieve a common objective...

s, and intentional communities regained popularity during this era. Early communities, such as the Hog Farm

Hog Farm

The Hog Farm is an organization considered to be America's longest running hippie commune. With beginnings as an actual collective hog farm in Tujunga, California, the group, founded in the 1960s by peace activist and clown Wavy Gravy, evolved into a "mobile, hallucination-extended family", active...

in the United States and Findhorn

Findhorn

Findhorn is a village in Moray, Scotland. It is located on the eastern shore of Findhorn Bay and immediately south of the Moray Firth. Findhorn is 3 miles northwest of Kinloss, and about 5 miles by road from Forres....

in Europe were established as straightforward agrarian attempts to return to the land and live free of interference from outside influences. As the era progressed, many people established and populated new communities in response to not only disillusionment with standard community forms, but also dissatisfaction with certain elements of the counterculture itself. Some of these self-sustaining communities have been credited with the birth and propagation of the international Green Movement

Green Movement

The Green Movement refers to a series of actions after the 2009 Iranian presidential election, in which protesters demanded the removal of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from office...

. (see also: recycling

Recycling

Recycling is processing used materials into new products to prevent waste of potentially useful materials, reduce the consumption of fresh raw materials, reduce energy usage, reduce air pollution and water pollution by reducing the need for "conventional" waste disposal, and lower greenhouse...

)

The emergence of an interest in expanded spiritual consciousness, yoga

Yoga

Yoga is a physical, mental, and spiritual discipline, originating in ancient India. The goal of yoga, or of the person practicing yoga, is the attainment of a state of perfect spiritual insight and tranquility while meditating on Supersoul...

, occult

Occult

The word occult comes from the Latin word occultus , referring to "knowledge of the hidden". In the medical sense it is used to refer to a structure or process that is hidden, e.g...

practices and increased human potential

Human Potential Movement

The Human Potential Movement arose out of the social and intellectual milieu of the 1960s and formed around the concept of cultivating extraordinary potential that its advocates believed to lie largely untapped in all people...

helped to shift views on organized religion

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

during the era. In 1957, 69% of Americans polled by Gallup

The Gallup Organization

The Gallup Organization, is primarily a research-based performance-management consulting company. Some of Gallup's key practice areas are - Employee Engagement, Customer Engagement and Well-Being. Gallup has over 40 offices in 27 countries. World headquarters are in Washington, D.C. Operational...

said religion was increasing in influence. By the late 1960s, polls indicated less than 20% still held that belief.

The often violent confrontations between college students (and other activists) and law enforcement officials became one of the hallmarks of the era. Many younger people began to show deep distrust of police, and terms such as “fuzz

Fuzz

Fuzz may refer to:*Vellus, a type of short, fine body hair on an animal*Tomentum, a filamentous hairlike growth on a plant*Focus , a blur effect*Fuzzbox, an electric guitar distortion effect*A derogatory slang term for the police...

” and “pig

Pig

A pig is any of the animals in the genus Sus, within the Suidae family of even-toed ungulates. Pigs include the domestic pig, its ancestor the wild boar, and several other wild relatives...

” as derogatory euphemisms for police became part of the counterculture lexicon

Lexicon

In linguistics, the lexicon of a language is its vocabulary, including its words and expressions. A lexicon is also a synonym of the word thesaurus. More formally, it is a language's inventory of lexemes. Coined in English 1603, the word "lexicon" derives from the Greek "λεξικόν" , neut...

. This distrust was based not only on fear of police brutality

Police brutality

Police brutality is the intentional use of excessive force, usually physical, but potentially also in the form of verbal attacks and psychological intimidation, by a police officer....

during political protests, but also on generalized police corruption — especially police manufacture of false evidence, and outright entrapment, in drug cases. The social tension between the counterculture and law enforcement reached the breaking point in many notable cases: the Columbia University protests of 1968

Columbia University protests of 1968

The Columbia University protests of 1968 were among the many student demonstrations that occurred around the world in that year. The Columbia protests erupted over the spring of that year after students discovered links between the university and the institutional apparatus supporting the United...

in New York City, the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests in Chicago, the arrest and imprisonment of John Sinclair

John Sinclair (poet)

John Sinclair is a Detroit poet, one-time manager of the band MC5, and leader of the White Panther Party — a militantly anti-racist countercultural group of white socialists seeking to assist the Black Panthers in the Civil Rights movement — from November 1968 to July 1969...

in Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ann Arbor is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the county seat of Washtenaw County. The 2010 census places the population at 113,934, making it the sixth largest city in Michigan. The Ann Arbor Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 344,791 as of 2010...

, and the Kent State shootings

Kent State shootings

The Kent State shootings—also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre—occurred at Kent State University in the city of Kent, Ohio, and involved the shooting of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard on Monday, May 4, 1970...

incident at Kent State University

Kent State University

Kent State University is a public research university located in Kent, Ohio, United States. The university has eight campuses around the northeast Ohio region with the main campus in Kent being the largest...

in Ohio.

The Vietnam War, and the protracted national divide between supporters and opponents of the war, were arguably the most important factors contributing to the rise of the larger counterculture movement. The widely-accepted assertion that anti-war opinion was predominantly held only among the young is a myth, but enormous war protests consisting of thousands of mostly younger people in every major American city effectively united the millions of Americans against the war, and against the war policy that prevailed under five congresses and during two presidential administrations.

The era essentially commenced in earnest with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. It ended with the termination of U.S. combat military involvement in the communist insurgencies of Southeast Asia and the end of the military draft

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

in 1973, and ultimately with the resignation of disgraced President Richard M. Nixon in August, 1974.

Many key movements were born of, or were advanced within, the counterculture of the 1960s. Each movement is relevant to the larger era. The most important stand alone, irrespective of the larger counterculture.

In Europe

The counterculture movement took hold in Western Europe, with LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

, Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

and West Berlin

West Berlin

West Berlin was a political exclave that existed between 1949 and 1990. It comprised the western regions of Berlin, which were bordered by East Berlin and parts of East Germany. West Berlin consisted of the American, British, and French occupation sectors, which had been established in 1945...

rivaling San Francisco and New York as counterculture centers. One manifestation of this was the French general strike that took place in Paris in May 1968, which nearly toppled the French government. Another was the German Student Movement

German student movement

The German student movement was a protest movement that took place during the late 1960s in West Germany. It was largely a reaction against the perceived authoritarianism and hypocrisy of the German government and other Western governments, and the poor living conditions of students...

of the 1960s.

In Central Europe, young people adopted the song "San Francisco" as an anthem for freedom, and it was widely played during Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

's 1968 "Prague Spring

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia during the era of its domination by the Soviet Union after World War II...

", a premature attempt to break away from Soviet repression. In reaction to Israel's Six-Day War

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War , also known as the June War, 1967 Arab-Israeli War, or Third Arab-Israeli War, was fought between June 5 and 10, 1967, by Israel and the neighboring states of Egypt , Jordan, and Syria...

, the Kremlin

Kremlin

A kremlin , same root as in kremen is a major fortified central complex found in historic Russian cities. This word is often used to refer to the best-known one, the Moscow Kremlin, or metonymically to the government that is based there...

decided to force Jewish minorities in all Soviet-dominated states to emigrate. This resulted in riots in Warsaw, Poland

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

and several other major cities.

As the newly emergent youth class began to criticize the established social order, new theories about cultural and personal identity began to spread, and traditional non-Western ideas — particularly with regard to religion, social organization and spiritual enlightenment — were more frequently embraced.

In Mexico

In Mexico, rock music was tied into the youth revolt of the 1960s. Cities such as Mexico City, as well as northern cities such as MonterreyMonterrey

Monterrey , is the capital city of the northeastern state of Nuevo León in the country of Mexico. The city is anchor to the third-largest metropolitan area in Mexico and is ranked as the ninth-largest city in the nation. Monterrey serves as a commercial center in the north of the country and is the...

, Nuevo Laredo

Nuevo Laredo

Nuevo Laredo is a city located in the Municipality of Nuevo Laredo in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. The city lies on the banks of the Río Grande, across from the United States city of Laredo, Texas. The 2010 census population of the city was 373,725. Nuevo Laredo is part of the Laredo-Nuevo...

, Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juárez , officially known today as Heroica Ciudad Juárez, but abbreviated Juárez and formerly known as El Paso del Norte, is a city and seat of the municipality of Juárez in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Juárez's estimated population is 1.5 million people. The city lies on the Rio Grande...

, and Tijuana

Tijuana

Tijuana is the largest city on the Baja California Peninsula and center of the Tijuana metropolitan area, part of the international San Diego–Tijuana metropolitan area. An industrial and financial center of Mexico, Tijuana exerts a strong influence on economics, education, culture, art, and politics...

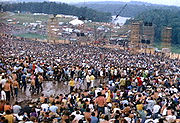

, were exposed to American music. Many Mexican rock stars became involved in the counterculture. The three-day Festival Rock y Ruedas de Avándaro

Festival Rock y Ruedas de Avándaro

Festival Rock y Ruedas de Avándaro was a rock concert that took place on the night of Saturday, September 11, 1971 and became known as a milestone in the history of Mexican rock music...

, held in 1971, was organized in the valley of Avándaro near the city of Toluca

Toluca

Toluca, formally known as Toluca de Lerdo, is the state capital of Mexico State as well as the seat of the Municipality of Toluca. It is the center of a rapidly growing urban area, now the fifth largest in Mexico. It is located west-southwest of Mexico City and only about 40 minutes by car to the...

, a town neighboring Mexico City, and became known as "The Mexican Woodstock". Nudity, drug use, and the presence of the American flag scandalized conservative Mexican society to such an extent that the government clamped down on rock and roll performances for the rest of the decade. The festival, marketed as proof of Mexico's modernization, was never expected to attract the masses it did, and the government had to evacuate stranded attendees en masse at the end. This occurred during the era of President

President of Mexico

The President of the United Mexican States is the head of state and government of Mexico. Under the Constitution, the president is also the Supreme Commander of the Mexican armed forces...

Luis Echeverría

Luis Echeverría

Luis Echeverría Álvarez served as President of Mexico from 1970 to 1976.-Early history:Echeverría joined the faculty of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 1947 and taught political theory...

, an extremely repressive era in Mexican history. Anything that could possibly be connected to the counterculture or student protests was prohibited from being broadcast on public airwaves, with the government fearing a repeat of the student protests

Tlatelolco massacre

The Tlatelolco massacre, also known as The Night of Tlatelolco , was a government massacre of student and civilian protesters and bystanders that took place during the afternoon and night of October 2, 1968, in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City...

of 1968. Few bands survived the prohibition; though the ones that did, like Three Souls in My Mind (now El Tri), remained popular due in part to their adoption of Spanish for their lyrics, but mostly as a result of a dedicated underground following. While Mexican rock groups were eventually able to perform publicly by the mid-1980s, the ban prohibiting tours of Mexico by foreign acts lasted until 1991.

Civil Rights Movement

The American Civil Rights Movement, a key element of the larger Counterculture movement, involved the use of applied nonviolenceNonviolence

Nonviolence has two meanings. It can refer, first, to a general philosophy of abstention from violence because of moral or religious principle It can refer to the behaviour of people using nonviolent action Nonviolence has two (closely related) meanings. (1) It can refer, first, to a general...

to assure that equal rights guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution would apply to all citizens. Many states illegally denied many of these rights to African Americans, and this was successfully addressed in the early and mid-1960s in several major nonviolent movements.

Free Speech Movement

Much of the 1960s counterculture originated on college campuses. The 1964 Free Speech Movement at the University of California, BerkeleyUniversity of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

, which had its roots in the Civil Rights Movement

Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

of the American South, was one early example. At Berkeley a group of students began to identify themselves as having interests as a class that were at odds with the interests and practices of the University and its corporate sponsors. Other rebellious young people, who were not students, also contributed to the Free Speech Movement.

New Left

The New Left is a term used in different countries to describe left-wing movements that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. They differed from earlier leftist movements that had been more oriented towards labour

Labour movement

The term labour movement or labor movement is a broad term for the development of a collective organization of working people, to campaign in their own interest for better treatment from their employers and governments, in particular through the implementation of specific laws governing labour...

activism, and instead adopted social activism. The U.S. "New Left" is associated with college campus mass protests and radical leftist movements. The British "New Left" was an intellectually driven movement which attempted to correct the perceived errors of "Old Left" parties in the post-World War II period. The movements began to wind down in the 1970s, when activists either committed themselves to party projects, developed social justice

Social justice

Social justice generally refers to the idea of creating a society or institution that is based on the principles of equality and solidarity, that understands and values human rights, and that recognizes the dignity of every human being. The term and modern concept of "social justice" was coined by...

organizations, moved into identity politics

Identity politics

Identity politics are political arguments that focus upon the self interest and perspectives of self-identified social interest groups and ways in which people's politics may be shaped by aspects of their identity through race, class, religion, sexual orientation or traditional dominance...

or alternative lifestyles, or became politically inactive.

Anti-War Movement

In Trafalgar SquareTrafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square is a public space and tourist attraction in central London, England, United Kingdom. At its centre is Nelson's Column, which is guarded by four lion statues at its base. There are a number of statues and sculptures in the square, with one plinth displaying changing pieces of...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 1958, in an act of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government, or of an occupying international power. Civil disobedience is commonly, though not always, defined as being nonviolent resistance. It is one form of civil resistance...

, 60,000–100,000 peace-loving protesters made up of students and pacifists converged in what was to become the “ban the Bomb” demonstrations.

Opposition to the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

began in 1964 on United States college campuses. Student activism became a dominant theme among the baby boomers, growing to include many Americans. Exemptions and deferments for the middle and upper classes resulted in the induction of a disproportionate number of poor, working-class, and minority registrants. Countercultural books such as MacBird

MacBird

MacBird! was a 1967 satire by Barbara Garson that superimposed the transferral of power following the Kennedy assassination onto the plot of Shakespeare's Macbeth....

by Barbara Garson

Barbara Garson

Barbara Garson is an American playwright, author and social activist.Garson is best known for the play MacBird, a notorious 1966 counterculture drama/political parody of Macbeth that sold over half a million copies as a book and had over 90 productions world wide...

and much of the counterculture music encouraged a spirit of non-conformism and anti-establishmentarianism. By 1968, the year after a large march to the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

and a large protest at the Pentagon

The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense, located in Arlington County, Virginia. As a symbol of the U.S. military, "the Pentagon" is often used metonymically to refer to the Department of Defense rather than the building itself.Designed by the American architect...

were undertaken, a majority of Americans opposed the war.

Feminism

The role of women as full-time homemakers in industrial society was challenged in 1963, when American feminist Betty FriedanBetty Friedan

Betty Friedan was an American writer, activist, and feminist.A leading figure in the Women's Movement in the United States, her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique is often credited with sparking the "second wave" of American feminism in the twentieth century...

published The Feminine Mystique

The Feminine Mystique

The Feminine Mystique, published February 19, 1963, by W.W. Norton and Co., is a nonfiction book written by Betty Friedan. It is widely credited with sparking the beginning of second-wave feminism in the United States....

, giving momentum to the women's movement and influencing what many called Second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism

The Feminist Movement, or the Women's Liberation Movement in the United States refers to a period of feminist activity which began during the early 1960s and lasted through the early 1990s....

. Other activists, such as Gloria Steinem

Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem is an American feminist, journalist, and social and political activist who became nationally recognized as a leader of, and media spokeswoman for, the women's liberation movement in the late 1960s and 1970s...

and Angela Davis

Angela Davis

Angela Davis is an American political activist, scholar, and author. Davis was most politically active during the late 1960s through the 1970s and was associated with the Communist Party USA, the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panther Party...

, either organized, influenced, or educated many of a younger generation of women to endorse and expand feminist thought.

Environmentalism

Counterculture environmentalists were quick to grasp the early (i.e., 1970s) analyses of the reality and the import of the Hubbert "peak oilPeak oil

Peak oil is the point in time when the maximum rate of global petroleum extraction is reached, after which the rate of production enters terminal decline. This concept is based on the observed production rates of individual oil wells, projected reserves and the combined production rate of a field...

" prediction. More broadly they saw that the dilemmas of energy derivation would have implications for geo-politics, lifestyle, environment, and other dimensions of modern life.

Gay Liberation Movement

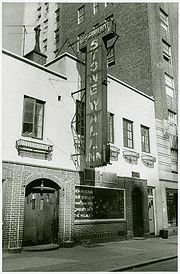

The Stonewall riots

Stonewall riots

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City...

were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn

Stonewall Inn

The Stonewall Inn, often shortened to Stonewall is an American bar in New York City and the site of the Stonewall riots of 1969, which are widely considered to be the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for gay and lesbian rights in the United...

, a gay bar in the Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, , , , .in New York often simply called "the Village", is a largely residential neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City. A large majority of the district is home to upper middle class families...

neighborhood of New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. This is frequently cited as the first instance in American history when people in the homosexual community fought back against a government-sponsored system that persecuted sexual minorities, and became the defining event that marked the start of the Gay Rights Movement in the United States and around the world.

Hippies

After the January 14, 1967 Human Be-InHuman Be-In

The Human Be-In was a happening in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, the afternoon and evening of January 14, 1967. It was a prelude to San Francisco's Summer of Love, which made the Haight-Ashbury district a symbol as the center of an American counterculture and introduced the word 'psychedelic'...

in San Francisco organized by artist Michael Bowen

Michael Bowen (artist)

Michael Bowen was an American fine artist known as one of the co-founders of the late 20th and 21st century Visionary art movements...

, the media's attention on the counterculture was fully activated. In 1967 Scott McKenzie

Scott McKenzie

Scott McKenzie is an American singer. He is best known for his 1967 hit single and generational anthem, "San Francisco ".-Life and career:...

's rendition of the song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)

San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)

"San Francisco " is a song, written by John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas, and sung by Scott McKenzie. It was written and released in 1967 to promote the Monterey Pop Festival....

" brought as many as 100,000 young people from all over the world to celebrate San Francisco's "Summer of Love

Summer of Love

The Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people converged on the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, creating a cultural and political rebellion...

."

While the song had originally been written by John Phillips

John Phillips (musician)

John Edmund Andrew Phillips , was an American singer, guitarist, songwriter and promoter . Known as Papa John, Phillips was a member and leader of the singing group The Mamas & the Papas...

of The Mamas & the Papas

The Mamas & the Papas

The Mamas & the Papas were a Canadian/American vocal group of the 1960s . The group recorded and performed from 1965 to 1968 with a short reunion in 1971, releasing five albums and 11 Top 40 hit singles...

to promote the June 1967 Monterey Pop Festival

Monterey Pop Festival

The Monterey International Pop Music Festival was a three-day concert event held June 16 to June 18, 1967 at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California...

, it became an instant hit worldwide (#4 in the United States, #1 in Europe) and quickly transcended its original purpose.

San Francisco's flower children, also called "hippies" by local newspaper columnist Herb Caen

Herb Caen

Herbert Eugene Caen was a Pulitzer Prize-winning San Francisco journalistwhose daily column of local goings-on, social and political happenings,...

, adopted new styles of dress, experimented with psychedelic drugs, lived communally and developed a vibrant music scene. When people returned home from "The Summer of Love" these styles and behaviors spread quickly from San Francisco and Berkeley to many U.S. and Canadian cities and European capitals. Some hippies formed communes to live as far outside of the established system as possible. This aspect of the counterculture rejected active political engagement with the mainstream and, following the dictate of Timothy Leary

Timothy Leary

Timothy Francis Leary was an American psychologist and writer, known for his advocacy of psychedelic drugs. During a time when drugs like LSD and psilocybin were legal, Leary conducted experiments at Harvard University under the Harvard Psilocybin Project, resulting in the Concord Prison...

to "Turn on, tune in, drop out

Turn on, tune in, drop out

"Turn on, tune in, drop out" is a counterculture phrase popularized by Timothy Leary in 1967. Leary spoke at the Human Be-In, a gathering of 30,000 hippies in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco and uttered the famous phrase, "Turn on, tune in, drop out". In a 1988 interview with Neil Strauss, Leary...

", hoped to change society by dropping out

Dropping out

Dropping out means leaving a group for either practical reasons, necessities or disillusionment with the system from which the individual in question leaves....

of it. Looking back on his own life (as a Harvard professor) prior to 1960, Leary interpreted it to have been that of "an anonymous institutional employee who drove to work each morning in a long line of commuter cars and drove home each night and drank martinis .... like several million middle-class, liberal, intellectual robots."

As members of the hippie movement grew older and moderated their lives and their views, and especially after US involvement in the Vietnam War ended in the mid-1970s, the counterculture was largely absorbed by the mainstream, leaving a lasting impact on philosophy, morality, music, art, alternative health and diet, lifestyle and fashion.

Marijuana, LSD, and other recreational drugs

During the 1960s, this second 'group' of casual LSD users evolved and expanded into a subcultureSubculture

In sociology, anthropology and cultural studies, a subculture is a group of people with a culture which differentiates them from the larger culture to which they belong.- Definition :...

that extolled the mystical and religious

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

symbolism often engendered by the drug's powerful effects, and advocated its use as a method of raising consciousness

Consciousness

Consciousness is a term that refers to the relationship between the mind and the world with which it interacts. It has been defined as: subjectivity, awareness, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind...

. The personalities associated with the subculture, gurus such as Dr. Timothy Leary and psychedelic rock

Psychedelic rock

Psychedelic rock is a style of rock music that is inspired or influenced by psychedelic culture and attempts to replicate and enhance the mind-altering experiences of psychedelic drugs. It emerged during the mid 1960s among folk rock and blues rock bands in United States and the United Kingdom...

musicians such as the Grateful Dead

Grateful Dead

The Grateful Dead was an American rock band formed in 1965 in the San Francisco Bay Area. The band was known for its unique and eclectic style, which fused elements of rock, folk, bluegrass, blues, reggae, country, improvisational jazz, psychedelia, and space rock, and for live performances of long...

, Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix was an American guitarist and singer-songwriter...

, Jefferson Airplane

Jefferson Airplane

Jefferson Airplane was an American rock band formed in San Francisco in 1965. A pioneer of the psychedelic rock movement, Jefferson Airplane was the first band from the San Francisco scene to achieve mainstream commercial and critical success....

and The Beatles

The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, active throughout the 1960s and one of the most commercially successful and critically acclaimed acts in the history of popular music. Formed in Liverpool, by 1962 the group consisted of John Lennon , Paul McCartney , George Harrison and Ringo Starr...

soon attracted a great deal of publicity, generating further interest in LSD.

The popularization of LSD outside of the medical world was hastened when individuals such as Ken Kesey

Ken Kesey

Kenneth Elton "Ken" Kesey was an American author, best known for his novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest , and as a counter-cultural figure who considered himself a link between the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s. "I was too young to be a beatnik, and too old to be a...

participated in drug trials and liked what they saw. Tom Wolfe wrote a widely read account of these early days of LSD's entrance into the non-academic world in his book The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, which documented the cross-country, acid-fueled voyage of Ken Kesey

Ken Kesey

Kenneth Elton "Ken" Kesey was an American author, best known for his novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest , and as a counter-cultural figure who considered himself a link between the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s. "I was too young to be a beatnik, and too old to be a...

and the Merry Pranksters on the psychedelic bus "Furthur" and the Pranksters' later 'Acid Test' LSD parties.

In 1965, Sandoz

Sandoz

Founded in 2003, Sandoz presently is the generic drug subsidiary of Novartis, a multinational pharmaceutical company. The company develops, manufactures and markets generic drugs as well as pharmaceutical and biotechnological active ingredients....

laboratories stopped its still legal shipments of LSD to the United States for research and psychiatric use, after a request from the U.S. government concerned about its use.

By April 1966, LSD use had become so widespread that Time Magazine warned about its dangers.

In December 1966, the exploitation film

Exploitation film

Exploitation film is a type of film that is promoted by "exploiting" often lurid subject matter. The term "exploitation" is common in film marketing, used for all types of films to mean promotion or advertising. These films then need something to exploit, such as a big star, special effects, sex,...

Hallucination Generation

Hallucination Generation

Hallucination Generation is a 1966 film by Edward Mann. Purportedly intended as a warning against the dangers of pill-popping Sixties hedonism along the lines of 1936's Reefer Madness, the film's primary purpose appears to have been titillation, thus landing it in the genre of exploitation...

was released. This was followed by The Trip (film)

The Trip (1967 film)

The Trip is a cult film released by American International Pictures, directed by Roger Corman, written by Jack Nicholson, and shot on location in and around Los Angeles, including on top of Kirkwood in Laurel Canyon, Hollywood Hills, and near Big Sur, California in 1966...

in 1967 and Psych-Out

Psych-Out

Psych-Out is a feature film about hippies, psychedelic music, and recreational drugs, produced and released by American International Pictures. Originally scripted as The Love Children, the title when tested caused people to think it was about bastards, so Samuel Z...

in 1968.

Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters

Ken KeseyKen Kesey

Kenneth Elton "Ken" Kesey was an American author, best known for his novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest , and as a counter-cultural figure who considered himself a link between the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s. "I was too young to be a beatnik, and too old to be a...

and his Merry Pranksters

Merry Pranksters

The Merry Pranksters were a group of people who formed around American author Ken Kesey in 1964 and sometimes lived communally at his homes in California and Oregon...

helped shape the developing character of the 1960s counterculture when they embarked on a cross-country voyage during the summer of 1964 in a psychedelic school bus named "Furthur." Beginning in 1959, Kesey had volunteered as a research subject for medical trials financed by the CIA's MK ULTRA

Project MKULTRA

Project MKULTRA, or MK-ULTRA, was the code name for a covert, illegal CIA human experimentation program, run by the CIA's Office of Scientific Intelligence. This official U.S. government program began in the early 1950s, continued at least through the late 1960s, and used U.S...

project. These trials tested the effects of LSD

LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide, abbreviated LSD or LSD-25, also known as lysergide and colloquially as acid, is a semisynthetic psychedelic drug of the ergoline family, well known for its psychological effects which can include altered thinking processes, closed and open eye visuals, synaesthesia, an...

, psilocybin

Psilocybin

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring psychedelic prodrug, with mind-altering effects similar to those of LSD and mescaline, after it is converted to psilocin. The effects can include altered thinking processes, perceptual distortions, an altered sense of time, and spiritual experiences, as well as...

, mescaline

Mescaline

Mescaline or 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine is a naturally occurring psychedelic alkaloid of the phenethylamine class used mainly as an entheogen....

, and other psychedelic drug

Psychedelic drug

A psychedelic substance is a psychoactive drug whose primary action is to alter cognition and perception. Psychedelics are part of a wider class of psychoactive drugs known as hallucinogens, a class that also includes related substances such as dissociatives and deliriants...

s. After the medical trials, Kesey continued experimenting on his own, and involved many close friends; collectively they became known as "The Merry Pranksters." The Pranksters visited Harvard LSD proponent Timothy Leary

Timothy Leary

Timothy Francis Leary was an American psychologist and writer, known for his advocacy of psychedelic drugs. During a time when drugs like LSD and psilocybin were legal, Leary conducted experiments at Harvard University under the Harvard Psilocybin Project, resulting in the Concord Prison...

at his Millbrook

Millbrook, New York

Millbrook is a village in Dutchess County, New York, United States. It is often said to be a "low-key version of the Hamptons" and one of the wealthiest towns in New York State. Millbrook's estimated town population was 1,551 in 2008. Millbrook is located in the Hudson Valley, an hour and thirty...

, New York retreat, and experimentation with LSD

LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide, abbreviated LSD or LSD-25, also known as lysergide and colloquially as acid, is a semisynthetic psychedelic drug of the ergoline family, well known for its psychological effects which can include altered thinking processes, closed and open eye visuals, synaesthesia, an...

and other psychedelic

Psychedelic

The term psychedelic is derived from the Greek words ψυχή and δηλοῦν , translating to "soul-manifesting". A psychedelic experience is characterized by the striking perception of aspects of one's mind previously unknown, or by the creative exuberance of the mind liberated from its ostensibly...

drugs, primarily as a means for internal reflection and personal growth, became a constant during the Prankster trip.

The Pranksters created a direct link between the 1950s Beat Generation

Beat generation

The Beat Generation refers to a group of American post-WWII writers who came to prominence in the 1950s, as well as the cultural phenomena that they both documented and inspired...

and the 1960s psychedelic scene; the bus was driven by Beat icon Neal Cassady

Neal Cassady

Neal Leon Cassady was a major figure of the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the psychedelic movement of the 1960s. He served as the model for the character Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac's novel On the Road....

, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg

Irwin Allen Ginsberg was an American poet and one of the leading figures of the Beat Generation in the 1950s. He vigorously opposed militarism, materialism and sexual repression...

was onboard for a time, and they dropped in on Cassady's friend, Beat author Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac

Jean-Louis "Jack" Lebris de Kerouac was an American novelist and poet. He is considered a literary iconoclast and, alongside William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, a pioneer of the Beat Generation. Kerouac is recognized for his spontaneous method of writing, covering topics such as Catholic...

— though Kerouac declined to participate in the Prankster scene. After the Pranksters returned to California, they popularized the use of LSD at so-called "Acid Tests

Acid Tests

The Acid Tests were a series of parties held by Ken Kesey in the San Francisco Bay Area during the mid 1960s, centered entirely around the use of, experimentation with, and advocacy of, the psychedelic drug LSD, also known as "acid."...

", which initially were held at Kesey's home in La Honda, California

La Honda, California

La Honda is a census-designated place in southern San Mateo County, California, United States. The population was 928 at the 2010 census. It is located in the Santa Cruz Mountains between Silicon Valley and the Pacific coast of California...

, and then at many other West Coast venues.

Other Psychedelics

Experimentation with LSD, mescalineMescaline

Mescaline or 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine is a naturally occurring psychedelic alkaloid of the phenethylamine class used mainly as an entheogen....

, peyote

Peyote

Lophophora williamsii , better known by its common name Peyote , is a small, spineless cactus with psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline.It is native to southwestern Texas and Mexico...

, sacred mushrooms, and other psychedelic drugs became a major component of 1960s counterculture, influencing philosophy, art

Psychedelic art

Psychedelic art is any kind of visual artwork inspired by psychedelic experiences induced by drugs such as LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin. The word "psychedelic" "mind manifesting". By that definition all artistic efforts to depict the inner world of the psyche may be considered "psychedelic"...

, music and styles of dress.

Sexual revolution

Beginning in San Francisco in the mid 1960s, a new culture of "free loveFree love

The term free love has been used to describe a social movement that rejects marriage, which is seen as a form of social bondage. The Free Love movement’s initial goal was to separate the state from sexual matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery...

" arose, with millions of young people embracing the hippie ethos and preaching the power of love and the beauty of sex as a natural part of ordinary life. By the start of the 1970s it was acceptable for colleges to allow co-educational housing where male and female students mingled freely. This aspect of the counterculture continues to impact modern society.

Alternative media

Underground newspapers sprang up in most cities and college towns, serving to define and communicate the range of phenomena that defined the counterculture: radical political opposition to "The EstablishmentThe Establishment

The Establishment is a term used to refer to a visible dominant group or elite that holds power or authority in a nation. The term suggests a closed social group which selects its own members...

", colorful experimental (and often explicitly drug-influenced) approaches to art, music and cinema, and uninhibited indulgence in sex and drugs as a symbol of freedom. The papers also often included comic strips, from which the underground comix

Underground comix

Underground comix are small press or self-published comic books which are often socially relevant or satirical in nature. They differ from mainstream comics in depicting content forbidden to mainstream publications by the Comics Code Authority, including explicit drug use, sexuality and violence...

were an outgrowth.

Avant-garde art and anti-art

The Situationist International was a restricted group of international revolutionaries founded in 1957, and which had its peak in its influence on the unprecedented generalGeneral strike

A general strike is a strike action by a critical mass of the labour force in a city, region, or country. While a general strike can be for political goals, economic goals, or both, it tends to gain its momentum from the ideological or class sympathies of the participants...

wildcat strikes of May 1968 in France. With their ideas rooted in Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

and the 20th-century European artistic avant-garde

Avant-garde

Avant-garde means "advance guard" or "vanguard". The adjective form is used in English to refer to people or works that are experimental or innovative, particularly with respect to art, culture, and politics....

s, they advocated experiences of life being alternative to those admitted by the capitalist order

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, for the fulfillment of human primitive desires and the pursuing of a superior passional quality. For this purpose they suggested and experimented with the construction of situations, namely the setting up of environments favorable for the fulfillment of such desires. Using methods drawn from the arts, they developed a series of experimental fields of study for the construction of such situations, like unitary urbanism

Unitary Urbanism

Unitary urbanism was the critique of status quo urbanism employed by the Lettrist International and then further developed by the Situationist International between approximately 1953 and 1960....

and psychogeography

Psychogeography

Psychogeography was defined in 1955 by Guy Debord as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals." Another definition is "a whole toy box full of playful, inventive strategies for...

. They fought against the main obstacle on the fulfillment of such superior passional living, identified by them in advanced capitalism

Advanced capitalism

In political philosophy, advanced capitalism is the situation that pertains in a society in which the capitalist model has been integrated and developed deeply and extensively and for a prolonged period of time...

. Their theoretical work peaked on the highly influential book The Society of the Spectacle

The Society of the Spectacle

The Society of the Spectacle is a work of philosophy and critical theory by Guy Debord. It was first published in 1967 in France.-Book structure:...

by Guy Debord

Guy Debord

Guy Ernest Debord was a French Marxist theorist, writer, filmmaker, member of the Letterist International, founder of a Letterist faction, and founding member of the Situationist International . He was also briefly a member of Socialisme ou Barbarie.-Early Life:Guy Debord was born in Paris in 1931...

. Debord argued in 1967 that spectacular features like mass media

Mass media

Mass media refers collectively to all media technologies which are intended to reach a large audience via mass communication. Broadcast media transmit their information electronically and comprise of television, film and radio, movies, CDs, DVDs and some other gadgets like cameras or video consoles...

and advertising

Advertising

Advertising is a form of communication used to persuade an audience to take some action with respect to products, ideas, or services. Most commonly, the desired result is to drive consumer behavior with respect to a commercial offering, although political and ideological advertising is also common...

have a central role in an advanced capitalist society, which is to show a fake reality in order to mask the real capitalist degradation of human life.

Fluxus

Fluxus

Fluxus—a name taken from a Latin word meaning "to flow"—is an international network of artists, composers and designers noted for blending different artistic media and disciplines in the 1960s. They have been active in Neo-Dada noise music and visual art as well as literature, urban planning,...

— a name taken from a Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

word meaning "to flow" — is an international network of artists, composers and designers noted for blending different artistic media and disciplines in the 1960s. They have been active in Neo-Dada

Neo-Dada

Neo-Dada is a label applied primarily to audio and visual art that has similarities in method or intent to earlier Dada artwork. It is the foundation of Fluxus, Pop Art and Nouveau réalisme. Neo-Dada is exemplified by its use of modern materials, popular imagery, and absurdist contrast...

noise music

Noise music

Noise music is a term used to describe varieties of avant-garde music and sound art that may use elements such as cacophony, dissonance, atonality, noise, indeterminacy, and repetition in their realization. Noise music can feature distortion, various types of acoustically or electronically...

and visual art as well as literature

Literature

Literature is the art of written works, and is not bound to published sources...

, urban planning

Urban planning

Urban planning incorporates areas such as economics, design, ecology, sociology, geography, law, political science, and statistics to guide and ensure the orderly development of settlements and communities....

, architecture

Architecture

Architecture is both the process and product of planning, designing and construction. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural and political symbols and as works of art...

, and design

Design

Design as a noun informally refers to a plan or convention for the construction of an object or a system while “to design” refers to making this plan...

. Fluxus is often described as intermedia

Intermedia

Intermedia was a concept employed in the mid-sixties by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins to describe the ineffable, often confusing, inter-disciplinary activities that occur between genres that became prevalent in the 1960s. Thus, the areas such as those between drawing and poetry, or between painting...

, a term coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins

Dick Higgins

Dick Higgins was a composer, poet, printer, and early Fluxus artist. Higgins was born in Cambridge, England, but raised in the United States in various parts of New England, including Worcester, Massachusetts, Putney, Vermont, and Concord, New Hampshire.Like other Fluxus artists, Higgins studied...

in a famous 1966 essay. Fluxus encouraged a "do-it-yourself" aesthetic, and valued simplicity over complexity. Like Dada

Dada

Dada or Dadaism is a cultural movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland, during World War I and peaked from 1916 to 1922. The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature—poetry, art manifestoes, art theory—theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a...

before it, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art

Anti-art

Anti-art is a loosely-used term applied to an array of concepts and attitudes that reject prior definitions of art and question art in general. Anti-art tends to conduct this questioning and rejection from the vantage point of art...

sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art world in favor of an artist-centered creative practice. As Fluxus artist Robert Filliou

Robert Filliou

Robert Filliou was a French Fluxus artist, who produced works as a filmmaker, "action poet," sculptor, and happenings maestro....

wrote, however, Fluxus differed from Dada in its richer set of aspirations, and the positive social and communitarian aspirations of Fluxus far outweighed the anti-art

Anti-art

Anti-art is a loosely-used term applied to an array of concepts and attitudes that reject prior definitions of art and question art in general. Anti-art tends to conduct this questioning and rejection from the vantage point of art...

tendency that also marked the group.

In the 1960s, the Dada

Dada

Dada or Dadaism is a cultural movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland, during World War I and peaked from 1916 to 1922. The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature—poetry, art manifestoes, art theory—theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a...

-influenced art group

Art group

An art group refers to an association of artists who may work communally, for the purpose of facilitating the creation of art, either that belonging to the individual, or the collective....

Black Mask

Black Mask (anarchists)