Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

Encyclopedia

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was the ceremony in which the newly ascended monarch, Elizabeth II, was crowned

Queen of the United Kingdom

, Canada

, Australia

, New Zealand

, South Africa

, Ceylon

, and Pakistan

, as well as taking on the role of Head of the Commonwealth

. Elizabeth ascended the thrones of these countries upon the death of her father, King George VI

on 6 February 1952, and was proclaimed queen

by her various privy and executive councils shortly afterward. The coronation, was held more than a year after the accession, on 2 June 1953; this followed the tradition that a festival such as a coronation was inappropriate during the period of mourning that followed the death of the preceding sovereign. In the coronation ceremony itself, Elizabeth swore an oath to uphold the laws of her nations

and, specifically for England

, to govern the Church of England

.

. Though Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary

died on 24 March, the dowager Queen had stated in her will

that her passing should not affect the planning of the coronation, and the event went ahead as scheduled.

Norman Hartnell

was commissioned by the Queen to design the outfits for all the members of the Royal Family and especially the dress Elizabeth would wear at the coronation; Hartnell's design for the latter evolved through nine proposals, the final reached by his own research as well as numerous personal meetings with the Queen. What resulted was a white silk dress embroidered with the floral emblems of the countries of the Commonwealth at the time: the Tudor rose

of England, the Scots thistle

, the Welsh leek

, shamrock

s for Ireland, the wattle

of Australia, the maple leaf

of Canada, the New Zealand fern

, South Africa's protea

, two lotus flowers

for India and Ceylon, and Pakistan's wheat

, cotton

, and jute

; unknown to the Queen at the time of the gown's delivery, though, was the unique four-leaf clover

embroidered on the dress' left side, where Elizabeth's hand would touch throughout the day.

Elizabeth, meanwhile, rehearsed for the upcoming day with her maids of honour, a sheet used in place of the velvet train and an arrangement of chairs standing in for the carriage. So that she could become accustomed to its feel and weight, the Queen also wore the Imperial State Crown

while she went about her daily business, sporting it at her desk, at tea, and while reading the newspaper. Elizabeth took part in two full rehearsals at Westminster Abbey

, on 22 and 29 May, though other sources assert that the Queen attended either "several" rehearsals or one. Typically, the Duchess of Norfolk

stood in for the Queen at rehearsals.

and clergy. However, for the new Queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different. The coronation of the Queen was the first ever to be televised (although the BBC Television Service had covered part of the procession from Westminster Abbey after her father's coronation in 1937), and was also the world's first major international event to be broadcast on television. There had been considerable debate within the British Cabinet

on the subject, with Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

against the idea; but, Elizabeth refused her British prime minister's advice on this matter and insisted the event take place before television cameras, as well as those filming with experimental 3-D technology

. Millions across Britain watched the coronation live, while, to make sure Canadians could see it on the same day, English Electric Canberra

s flew film of the ceremony across the Atlantic Ocean

to be broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

, the first non-stop flights between the United Kingdom and the Canadian mainland. In Goose Bay

, Newfoundland

, the film was transferred to a Royal Canadian Air Force

CF-100 jet fighter for the further trip to Montreal

. In all, three such voyages were made as the coronation proceeded.

Guests and officials passed in a procession before approximately three million spectators gathered in the streets of London

Guests and officials passed in a procession before approximately three million spectators gathered in the streets of London

, some having camped overnight in their spot to ensure a view of the monarch, and others having access to specially built bleachers and scaffolding along the route. For those not present to witness the event, more than 200 microphones were stationed along the path and in Westminster Abbey

, with 750 commentators broadcasting descriptions in 39 languages; more than twenty million viewers around the world watched the coverage. Military representation from throughout the Commonwealth marched in parade prior to the Queen's arrival, including the Canadian Coronation Contingent

.

The procession included foreign royalty and heads of state riding to Westminster Abbey in various carriages, so many that volunteers ranging from wealthy businessmen to rural landowners were required to fill the insufficient ranks of regular footmen. The first royal coach left Buckingham Palace

and moved down The Mall, which was filled with flag-waving and cheering crowds. It was followed by the Irish State Coach

carrying Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

, who wore the circlet of her crown bearing the Koh-i-Noor

diamond. Queen Elizabeth II proceeded through London from Buckingham Palace, through Trafalgar Square

, and towards the abbey in the Gold State Coach

. Attached to the shoulders of her dress, the Queen wore the Robe of State, a 5.5 metre (6 yard) long, hand woven silk velvet

cloak lined with Canadian ermine

that required the assistance of the Queen's maids of honour Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Lady Anne Coke, Lady Moyra Hamilton, Lady Mary Baillie-Hamilton, Lady Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby

, Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill, and the Duchess of Devonshire

to carry.

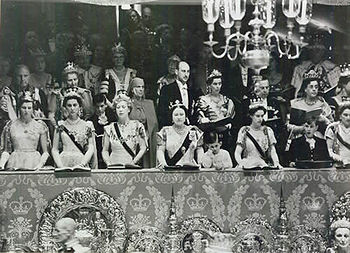

, Westminster Abbey was at 6am opened to the approximately 8,000 guests invited from across the Commonwealth of Nations

; more prominent individuals, such as members of the Queen's family and foreign royalty, the peers of the United Kingdom

, heads of state

, Members of Parliament

from the Queen's various legislatures, and the like, arrived after 8:30 am. From Canada came the Prime Minister

, Louis St. Laurent

, Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

Louis Breithaupt and his premier

, Leslie Frost

, as well as Premier of Saskatchewan

Tommy Douglas

, Quebec Cabinet ministers

Onésime Gagnon

and John Samuel Bourque

, Mayor of Toronto Allan A. Lamport

, and Chief of the Squamish Nation Joe Mathias. Tonga

's Queen Tupou III

was a guest, and was noted for her cheery demeanour even while riding in an open carriage through London in the rain.

Preceding the Queen into Westminster Abbey was St. Edward's Crown

Preceding the Queen into Westminster Abbey was St. Edward's Crown

, carried into the abbey by the Lord High Steward

of England

, then the Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope

, who was flanked by two other peers

, while the Archbishop

s and Bishops Assistant of the Church of England

, in their cope

s and mitre

s, waited outside the Great West Door for the arrival of the Queen. When this occurred at approximately 11:00 am, Elizabeth found that the friction between her robes and the carpet caused her difficulty moving forward, and she said to the Archbishop of Canterbury

, Geoffrey Fisher

, "get me started!" Once going, the procession, which included the various High Commissioners

of the Commonwealth carrying banners bearing the shields of the coats of arms of their respective nations, moved inside the abbey, up the central aisle and through the choir to the stage, as Psalms

122, 1–3, 6, and 7 were read and the choir sang out "Vivat Regina! Vivat Regina Elizabetha! Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!" As Elizabeth prayed at and then sat herself on the Chair of Estate to the south of the altar, the Bishops carried in the religious paraphernalia the bible

, paten

, and chalice

and the peers holding the coronation regalia handed it over to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who, in turn, passed them to the Dean of Westminster, Alan Campbell Don

, to be placed on the altar.

After the Queen moved to stand before King Edward's Chair

(Coronation Chair), she turned, following as Fisher, along with the Lord High Chancellor

of Great Britain (the Viscount Simonds

), Lord Great Chamberlain

of England (the Earl of Ancaster), Lord High Constable of England

(the Viscount Alanbrooke

), and Earl Marshal

of the United Kingdom (the Duke of Norfolk

), all led by the Garter Principal King of Arms

(George Bellew

), asked the audience in each direction of the compass separately: "Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Elizabeth, your undoubted Queen: wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?" The crowd would reply "God save Queen Elizabeth," every time, to each of which the Queen would curtsey in return.

Seated again on the Chair of Estate, Elizabeth then took the coronation Oath as administered by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the lengthy oath, the Queen swore to govern each of her countries according to their respective laws and customs, to mete out law and justice with mercy, to uphold Protestantism

in the United Kingdom and protect the Church of England and preserve its bishops and clergy. She proceeded to the altar where she stated "The things which I have here promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God," before kissing the Bible and putting the royal sign-manual

to the oath as the Bible was returned to the Dean of Westminster. From him the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

, James Pitt-Watson, took the Bible and presented it to the Queen again, saying "to keep your Majesty ever mindful of the law and the Gospel of God... we present you with this Book"; Elizabeth returned the book to Pitt-Watson, who placed it back with the Dean of Westminster.

The communion

service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace," before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter

, Psalms, and the Gospel of Matthew

. Elizabeth was then anointed

as the assembly sang "Zadok the Priest

"; the Queen's jewelry and crimson cape was removed by the Earl of Ancaster and the Mistress of the Robes

, the Duchess of Devonshire

, and, wearing only a simple, white linen dress also designed by Hartnell to completely cover the coronation gown, she moved to be seated in the Coronation Chair. There, Fisher, assisted by Don, made a cross on the Queen's forehead with holy oil

made from the same base as that which had been used in the coronation of her father. Because this segment of the ceremony was considered absolutely sacrosanct, it was concealed from the view of the television cameras by a silk canopy held above the Queen by four Knights of the Garter

. When this part of the coronation was complete, and the canopy removed, Don and the Duchess of Devonshire placed on the monarch the Colobium Sindonis

and Supertunica.

From the altar, the Dean of Westminster passed to the Lord Great Chamberlain the spur

s, which were presented to the Queen and then placed back on the altar. The Sword of State was then handed to Elizabeth, who, after a prayer was uttered by Fisher, placed it herself on the altar, and the peer who had been previously holding it took it back again after paying a sum of 100 shillings. The Queen was then invested with the Armills (bracelets), Stole Royal, Robe Royal, and the Sovereign's Orb, followed by the Queen's Ring, the Sceptre with the Cross

, and the Sceptre with the Dove

. With the first two items on and in her right hand and the latter in her left, Queen Elizabeth was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, with the crowd shouting "God save the Queen!" at the exact moment St. Edward's Crown

touched the monarch's head. The princes and peers gathered then put on their coronets and a 21-gun salute

was fired from the Tower of London

.

With the benediction read, Elizabeth moved to the throne and the Archbishop of Canterbury and all the Bishops offered to her their fealty, after which, as the choir sang, the peers of the United Kingdom led by the royal peers: the Queen's husband; Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

With the benediction read, Elizabeth moved to the throne and the Archbishop of Canterbury and all the Bishops offered to her their fealty, after which, as the choir sang, the peers of the United Kingdom led by the royal peers: the Queen's husband; Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

; and Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

each proceeded, in order of precedence, to pay their personal homage and allegiance to Elizabeth. When the last baron had completed this task, the assembly shouted "God save Queen Elizabeth. Long live Queen Elizabeth. May the Queen live for ever!" Having removed all her royal regalia, Elizabeth kneeled and took the communion, including a general confession

and absolution

, and, along with the audience, recited the Lord's Prayer

.

Now wearing the Imperial State Crown and holding the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb, and as the gathered guests sang "God Save the Queen

", Elizabeth left Westminster Abbey through the nave and apse, out the Great West Door, followed by members of the Royal Family, the clergy, her prime ministers, etc. Then, transported back to Buckingham Palace in the Gold State Coach, with an escort of thousands of military personnel from around the Commonwealth, the Queen appeared on the balcony of the Centre Room before a gathered crowd as a flypast

went overhead.

. Various pieces, both classical and contemporary, were used throughout the coronation ceremony. Canadian composer Healey Willan

was commissioned by the Queen to pen an anthem to be played during the homage.

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe Coronation chicken

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe Coronation chicken

was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment

. Further, street parties were mounted all over the United Kingdom. Two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine Collins Magazine rebranded itself as The Young Elizabethan

.

On the Korean Peninsula

, Canadian soldiers

serving in the Korean War

acknowledged the day by firing blue, red, and white coloured smoke shells at the enemy and drank rum rations in observance. In the United States

, coronation parties were mounted, one in New York City

attended by the Queen's uncle and aunt, the Duke

and Duchess of Windsor, while in Canada

, military tattoo

s, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted. In Newfoundland

, 90,000 boxes of candy were given to children, some getting theirs delivered by Royal Canadian Air Force

drops. In Quebec

, 400,000 people turned out in Montreal

, 100,000 at Jeanne-Mance Park

alone. A multicultural

show was put on at Exhibition Place

in Toronto

, square dances and exhibitions took place in the prairie provinces, and, in Vancouver

, the Chinese community performed a public lion dance

. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal

was presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's countries, and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. As with the coronation of George VI, acorns shed from oaks in Windsor Great Park

, around Windsor Castle

, were shipped around the Commonwealth and planted in parks, schoolyards, cemeteries, and private yards to grow into what are known as Royal Oaks or Coronation Oaks.

News that Edmund Hillary

and Tenzing Norgay

had reached the summit of Mount Everest

arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen".

The Coronation Cup

football tournament was held at Hampden Park

, Glasgow

in May 1953 to mark the Coronation.

Coronation

A coronation is a ceremony marking the formal investiture of a monarch and/or their consort with regal power, usually involving the placement of a crown upon their head and the presentation of other items of regalia...

Queen of the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is a country off the southern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Known until 1972 as Ceylon , Sri Lanka is an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait, and lies in the vicinity of India and the...

, and Pakistan

Pakistan

Pakistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a sovereign state in South Asia. It has a coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by Afghanistan and Iran in the west, India in the east and China in the far northeast. In the north, Tajikistan...

, as well as taking on the role of Head of the Commonwealth

Head of the Commonwealth

The Head of the Commonwealth heads the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation which currently comprises 54 sovereign states. The position is currently occupied by the individual who serves as monarch of each of the Commonwealth realms, but has no day-to-day involvement in the...

. Elizabeth ascended the thrones of these countries upon the death of her father, King George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

on 6 February 1952, and was proclaimed queen

Proclamation of accession of Elizabeth II

Queen Elizabeth II was proclaimed sovereign of each of the Commonwealth realms on 6 and 7 February 1952, after the death of her father, King George VI, in the night between 5 February and 6 February, and while the Princess was in Kenya....

by her various privy and executive councils shortly afterward. The coronation, was held more than a year after the accession, on 2 June 1953; this followed the tradition that a festival such as a coronation was inappropriate during the period of mourning that followed the death of the preceding sovereign. In the coronation ceremony itself, Elizabeth swore an oath to uphold the laws of her nations

Commonwealth Realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state within the Commonwealth of Nations that has Elizabeth II as its monarch and head of state. The sixteen current realms have a combined land area of 18.8 million km² , and a population of 134 million, of which all, except about two million, live in the six...

and, specifically for England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, to govern the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

.

Preparations

For the one-day coronation ceremony, which would cost $4 million, 16 months of preparation took place, with the first meeting of the Coronation Commission taking place in April 1952, under the chairmanship of the Queen's husband, Prince Philip, Duke of EdinburghPrince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh is the husband of Elizabeth II. He is the United Kingdom's longest-serving consort and the oldest serving spouse of a reigning British monarch....

. Though Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary

Mary of Teck

Mary of Teck was the queen consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, as the wife of King-Emperor George V....

died on 24 March, the dowager Queen had stated in her will

Will (law)

A will or testament is a legal declaration by which a person, the testator, names one or more persons to manage his/her estate and provides for the transfer of his/her property at death...

that her passing should not affect the planning of the coronation, and the event went ahead as scheduled.

Norman Hartnell

Norman Hartnell

Sir Norman Bishop Hartnell, KCVO was a British fashion designer. Royal Warrant as Dressmaker to HM The Queen 1940, subsequently Royal Warrant as Dressmaker to HM Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother...

was commissioned by the Queen to design the outfits for all the members of the Royal Family and especially the dress Elizabeth would wear at the coronation; Hartnell's design for the latter evolved through nine proposals, the final reached by his own research as well as numerous personal meetings with the Queen. What resulted was a white silk dress embroidered with the floral emblems of the countries of the Commonwealth at the time: the Tudor rose

Tudor rose

The Tudor Rose is the traditional floral heraldic emblem of England and takes its name and origins from the Tudor dynasty.-Origins:...

of England, the Scots thistle

Thistle

Thistle is the common name of a group of flowering plants characterised by leaves with sharp prickles on the margins, mostly in the family Asteraceae. Prickles often occur all over the plant – on surfaces such as those of the stem and flat parts of leaves. These are an adaptation that protects the...

, the Welsh leek

Leek

The leek, Allium ampeloprasum var. porrum , also sometimes known as Allium porrum, is a vegetable which belongs, along with the onion and garlic, to family Amaryllidaceae, subfamily Allioideae...

, shamrock

Shamrock

The shamrock is a three-leafed old white clover. It is known as a symbol of Ireland. The name shamrock is derived from Irish , which is the diminutive version of the Irish word for clover ....

s for Ireland, the wattle

Acacia

Acacia is a genus of shrubs and trees belonging to the subfamily Mimosoideae of the family Fabaceae, first described in Africa by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1773. Many non-Australian species tend to be thorny, whereas the majority of Australian acacias are not...

of Australia, the maple leaf

Maple leaf

The maple leaf is the characteristic leaf of the maple tree, and is the most widely recognized national symbol of Canada.-Use in Canada:At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the settlements of New France had attained a population of about 18,000...

of Canada, the New Zealand fern

Fern

A fern is any one of a group of about 12,000 species of plants belonging to the botanical group known as Pteridophyta. Unlike mosses, they have xylem and phloem . They have stems, leaves, and roots like other vascular plants...

, South Africa's protea

Protea

Protea is both the botanical name and the English common name of a genus of flowering plants, sometimes also called sugarbushes.-Etymology:...

, two lotus flowers

Nelumbo nucifera

Nelumbo nucifera, known by a number of names including Indian Lotus, Sacred Lotus, Bean of India, or simply Lotus, is a plant in the monogeneric family Nelumbonaceae...

for India and Ceylon, and Pakistan's wheat

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

, cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

, and jute

Jute

Jute is a long, soft, shiny vegetable fibre that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It is produced from plants in the genus Corchorus, which has been classified in the family Tiliaceae, or more recently in Malvaceae....

; unknown to the Queen at the time of the gown's delivery, though, was the unique four-leaf clover

Four-leaf clover

The four-leaf clover is an uncommon variation of the common, three-leaved clover. According to tradition, such leaves bring good luck to their finders, especially if found accidentally...

embroidered on the dress' left side, where Elizabeth's hand would touch throughout the day.

Elizabeth, meanwhile, rehearsed for the upcoming day with her maids of honour, a sheet used in place of the velvet train and an arrangement of chairs standing in for the carriage. So that she could become accustomed to its feel and weight, the Queen also wore the Imperial State Crown

Imperial State Crown

The Imperial State Crown is one of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom.- Design :The Crown is of a design similar to St Edward's Crown: it includes a base of four crosses pattée alternating with four fleurs-de-lis, above which are four half-arches surmounted by a cross. Inside is a velvet cap...

while she went about her daily business, sporting it at her desk, at tea, and while reading the newspaper. Elizabeth took part in two full rehearsals at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

, on 22 and 29 May, though other sources assert that the Queen attended either "several" rehearsals or one. Typically, the Duchess of Norfolk

Lavinia Fitzalan-Howard, Duchess of Norfolk

Lavinia Mary Fitzalan-Howard, Duchess of Norfolk LG CBE was a British peeress....

stood in for the Queen at rehearsals.

The event

The Coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a similar pattern to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peeragePeerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

and clergy. However, for the new Queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different. The coronation of the Queen was the first ever to be televised (although the BBC Television Service had covered part of the procession from Westminster Abbey after her father's coronation in 1937), and was also the world's first major international event to be broadcast on television. There had been considerable debate within the British Cabinet

Cabinet of the United Kingdom

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the collective decision-making body of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom, composed of the Prime Minister and some 22 Cabinet Ministers, the most senior of the government ministers....

on the subject, with Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

against the idea; but, Elizabeth refused her British prime minister's advice on this matter and insisted the event take place before television cameras, as well as those filming with experimental 3-D technology

3-D film

A 3-D film or S3D film is a motion picture that enhances the illusion of depth perception...

. Millions across Britain watched the coronation live, while, to make sure Canadians could see it on the same day, English Electric Canberra

English Electric Canberra

The English Electric Canberra is a first-generation jet-powered light bomber manufactured in large numbers through the 1950s. The Canberra could fly at a higher altitude than any other bomber through the 1950s and set a world altitude record of 70,310 ft in 1957...

s flew film of the ceremony across the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

to be broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, commonly known as CBC and officially as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian crown corporation that serves as the national public radio and television broadcaster...

, the first non-stop flights between the United Kingdom and the Canadian mainland. In Goose Bay

Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador

Happy Valley – Goose Bay is a Canadian town in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.Located in the central part of Labrador, the town is the largest population centre in that region. Incorporated in 1973, the town composes the former town of Happy Valley and the Local Improvement District of...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada. Situated in the country's Atlantic region, it incorporates the island of Newfoundland and mainland Labrador with a combined area of . As of April 2011, the province's estimated population is 508,400...

, the film was transferred to a Royal Canadian Air Force

Royal Canadian Air Force

The history of the Royal Canadian Air Force begins in 1920, when the air force was created as the Canadian Air Force . In 1924 the CAF was renamed the Royal Canadian Air Force and granted royal sanction by King George V. The RCAF existed as an independent service until 1968...

CF-100 jet fighter for the further trip to Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

. In all, three such voyages were made as the coronation proceeded.

Procession

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, some having camped overnight in their spot to ensure a view of the monarch, and others having access to specially built bleachers and scaffolding along the route. For those not present to witness the event, more than 200 microphones were stationed along the path and in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

, with 750 commentators broadcasting descriptions in 39 languages; more than twenty million viewers around the world watched the coverage. Military representation from throughout the Commonwealth marched in parade prior to the Queen's arrival, including the Canadian Coronation Contingent

Canadian Coronation Contingent

The Canadian Coronation Contingent is a guard of honour, composed of members of the Canadian Forces and Royal Canadian Mounted Police, assembled distinctly for participation in the coronation ceremonies of the Canadian monarch in London, England...

.

The procession included foreign royalty and heads of state riding to Westminster Abbey in various carriages, so many that volunteers ranging from wealthy businessmen to rural landowners were required to fill the insufficient ranks of regular footmen. The first royal coach left Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace, in London, is the principal residence and office of the British monarch. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is a setting for state occasions and royal hospitality...

and moved down The Mall, which was filled with flag-waving and cheering crowds. It was followed by the Irish State Coach

Irish State Coach

The Irish State Coach is an enclosed, four-horse-drawn carriage used by the British Royal Family. It is the traditional horse-drawn coach in which the British monarch travels from Buckingham Palace to the Palace of Westminster to formally open the new legislative session of the UK Parliament.The...

carrying Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon was the queen consort of King George VI from 1936 until her husband's death in 1952, after which she was known as Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, to avoid confusion with her daughter, Queen Elizabeth II...

, who wore the circlet of her crown bearing the Koh-i-Noor

Koh-i-Noor

The Kōh-i Nūr which means "Mountain of Light" in Persian, also spelled Koh-i-noor, Koh-e Noor or Koh-i-Nur, is a 105 carat diamond that was once the largest known diamond in the world. The Kōh-i Nūr originated in the state of Andhra Pradesh in India along with its double, the Darya-ye Noor...

diamond. Queen Elizabeth II proceeded through London from Buckingham Palace, through Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square is a public space and tourist attraction in central London, England, United Kingdom. At its centre is Nelson's Column, which is guarded by four lion statues at its base. There are a number of statues and sculptures in the square, with one plinth displaying changing pieces of...

, and towards the abbey in the Gold State Coach

Gold State Coach

The Gold State Coach is an enclosed, eight horse-drawn carriage used by the British Royal Family. It was built in the London workshops of Samuel Butler in 1762 and has been used at the coronation of every British monarch since George IV...

. Attached to the shoulders of her dress, the Queen wore the Robe of State, a 5.5 metre (6 yard) long, hand woven silk velvet

Velvet

Velvet is a type of woven tufted fabric in which the cut threads are evenly distributed,with a short dense pile, giving it a distinctive feel.The word 'velvety' is used as an adjective to mean -"smooth like velvet".-Composition:...

cloak lined with Canadian ermine

Stoat

The stoat , also known as the ermine or short-tailed weasel, is a species of Mustelid native to Eurasia and North America, distinguished from the least weasel by its larger size and longer tail with a prominent black tip...

that required the assistance of the Queen's maids of honour Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Lady Anne Coke, Lady Moyra Hamilton, Lady Mary Baillie-Hamilton, Lady Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby

Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 28th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby

Nancy Jane Marie Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 28th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby PC is the daughter of the late Gilbert James Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 3rd Earl of Ancaster and Nancy née Astor....

, Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill, and the Duchess of Devonshire

Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire

Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, GCVO, CBE was born Lady Mary Alice Gascoyne-Cecil, daughter of James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury...

to carry.

Guests

After being closed since the Queen's accession for coronation preparations, on Coronation DayCoronation Day

Coronation Day is the anniversary of the coronation of a monarch, the day a king or queen is formally crowned and invested with the regalia.-Coronation Day of Commonwealth realms monarchs:* Elizabeth II - 2 June 1953* George VI - 12 May 1937...

, Westminster Abbey was at 6am opened to the approximately 8,000 guests invited from across the Commonwealth of Nations

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

; more prominent individuals, such as members of the Queen's family and foreign royalty, the peers of the United Kingdom

Peerage of the United Kingdom

The Peerage of the United Kingdom comprises most peerages created in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the Act of Union in 1801, when it replaced the Peerage of Great Britain...

, heads of state

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

, Members of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

from the Queen's various legislatures, and the like, arrived after 8:30 am. From Canada came the Prime Minister

Prime Minister of Canada

The Prime Minister of Canada is the primary minister of the Crown, chairman of the Cabinet, and thus head of government for Canada, charged with advising the Canadian monarch or viceroy on the exercise of the executive powers vested in them by the constitution...

, Louis St. Laurent

Louis St. Laurent

Louis Stephen St. Laurent, PC, CC, QC , was the 12th Prime Minister of Canada from 15 November 1948, to 21 June 1957....

, Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

The Lieutenant Governor of Ontario is the viceregal representative in Ontario of the Canadian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, who operates distinctly within the province but is also shared equally with the ten other jurisdictions of Canada and resides predominantly in her oldest realm, the United...

Louis Breithaupt and his premier

Premier of Ontario

The Premier of Ontario is the first Minister of the Crown for the Canadian province of Ontario. The Premier is appointed as the province's head of government by the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, and presides over the Executive council, or Cabinet. The Executive Council Act The Premier of Ontario...

, Leslie Frost

Leslie Frost

Leslie Miscampbell Frost, was a politician in Ontario, Canada, who served as the 16th Premier from May 4, 1949 to November 8, 1961. Due to his lengthy tenure, he gained the nickname "Old Man Ontario".-Early years:...

, as well as Premier of Saskatchewan

Premier of Saskatchewan

The Premier of Saskatchewan is the first minister for the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. They are the province's head of government and de facto chief executive....

Tommy Douglas

Tommy Douglas

Thomas Clement "Tommy" Douglas, was a Scottish-born Baptist minister who became a prominent Canadian social democratic politician...

, Quebec Cabinet ministers

Executive Council of Quebec

The Executive Council of Quebec is the cabinet of the government of Quebec, Canada....

Onésime Gagnon

Onésime Gagnon

Onésime Gagnon, PC was a Canadian politician and the 20th Lieutenant Governor of Québec.-Background:He was born in Saint-Léon-de-Standon, Quebec on October 23, 1888 and was the son of Onésime Gagnon and Julie Morin. He was a Rhodes scholar and was called to the Quebec Bar in 1912...

and John Samuel Bourque

John Samuel Bourque

John Samuel Bourque was a Quebec politician, Cabinet Minister, military member and businessman. He was the Member of Legislative Assembly of Quebec for the riding of Sherbrooke for 25 years....

, Mayor of Toronto Allan A. Lamport

Allan A. Lamport

Allan Austin Lamport, CM was Mayor of Toronto, Canada, from 1952 to 1954. Known as "Lampy", his most notable achievement was his opposition to Toronto's Blue laws which banned virtually any activities on Sundays. Lamport fought to allow professional sporting activities on Sundays...

, and Chief of the Squamish Nation Joe Mathias. Tonga

Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga , is a state and an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, comprising 176 islands scattered over of ocean in the South Pacific...

's Queen Tupou III

Salote Tupou III of Tonga

Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tupou III, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DStJ , but usually named only Sālote, was Queen of Tonga from 5 April 1918 to her death in 1965.-Personal history:...

was a guest, and was noted for her cheery demeanour even while riding in an open carriage through London in the rain.

Ceremony

St. Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown was one of the English Crown Jewels and remains one of the senior British Crown Jewels, being the official coronation crown used in the coronation of first English, then British, and finally Commonwealth realms monarchs...

, carried into the abbey by the Lord High Steward

Lord High Steward

The position of Lord High Steward of England is the first of the Great Officers of State. The office has generally remained vacant since 1421, except at coronations and during the trials of peers in the House of Lords, when the Lord High Steward presides. In general, but not invariably, the Lord...

of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, then the Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope

Andrew Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope

Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Browne Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope KT, GCB, OM, DSO and two Bars , was a British admiral of the Second World War. Cunningham was widely known by his nickname, "ABC"....

, who was flanked by two other peers

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

, while the Archbishop

Archbishop

An archbishop is a bishop of higher rank, but not of higher sacramental order above that of the three orders of deacon, priest , and bishop...

s and Bishops Assistant of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, in their cope

Cope

The cope is a liturgical vestment, a very long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colour....

s and mitre

Mitre

The mitre , also spelled miter, is a type of headwear now known as the traditional, ceremonial head-dress of bishops and certain abbots in the Roman Catholic Church, as well as in the Anglican Communion, some Lutheran churches, and also bishops and certain other clergy in the Eastern Orthodox...

s, waited outside the Great West Door for the arrival of the Queen. When this occurred at approximately 11:00 am, Elizabeth found that the friction between her robes and the carpet caused her difficulty moving forward, and she said to the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, Geoffrey Fisher

Geoffrey Fisher

Geoffrey Francis Fisher, Baron Fisher of Lambeth, GCVO, PC was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1945 to 1961.-Background:...

, "get me started!" Once going, the procession, which included the various High Commissioners

High Commissioner (Commonwealth)

In the Commonwealth of Nations, a High Commissioner is the senior diplomat in charge of the diplomatic mission of one Commonwealth government to another.-History:...

of the Commonwealth carrying banners bearing the shields of the coats of arms of their respective nations, moved inside the abbey, up the central aisle and through the choir to the stage, as Psalms

Psalms

The Book of Psalms , commonly referred to simply as Psalms, is a book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Bible...

122, 1–3, 6, and 7 were read and the choir sang out "Vivat Regina! Vivat Regina Elizabetha! Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!" As Elizabeth prayed at and then sat herself on the Chair of Estate to the south of the altar, the Bishops carried in the religious paraphernalia the bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

, paten

Paten

A paten, or diskos, is a small plate, usually made of silver or gold, used to hold Eucharistic bread which is to be consecrated. It is generally used during the service itself, while the reserved hosts are stored in the Tabernacle in a ciborium....

, and chalice

Chalice (cup)

A chalice is a goblet or footed cup intended to hold a drink. In general religious terms, it is intended for drinking during a ceremony.-Christian:...

and the peers holding the coronation regalia handed it over to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who, in turn, passed them to the Dean of Westminster, Alan Campbell Don

Alan Campbell Don

Alan Campbell Don KCVO was a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery author of the Scottish Book of Common Prayer, Chaplain and Secretary to Cosmo Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury between 1931 and 1941, Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons between 1936 and 1946, and Dean of Westminster...

, to be placed on the altar.

After the Queen moved to stand before King Edward's Chair

King Edward's Chair

King Edward's Chair, sometimes known as St Edward's Chair or The Coronation Chair, is the throne on which the British monarch sits for the coronation. It was commissioned in 1296 by King Edward I to contain the coronation stone of Scotland — known as the Stone of Scone — which he had captured from...

(Coronation Chair), she turned, following as Fisher, along with the Lord High Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

of Great Britain (the Viscount Simonds

Gavin Simonds, 1st Viscount Simonds

Gavin Turnbull Simonds, 1st Viscount Simonds PC, KC was a British judge, politician and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.-Background and education:...

), Lord Great Chamberlain

Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable...

of England (the Earl of Ancaster), Lord High Constable of England

Lord High Constable of England

The Lord High Constable of England is the seventh of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Great Chamberlain and above the Earl Marshal. His office is now called out of abeyance only for coronations. The Lord High Constable was originally the commander of the royal armies and the...

(the Viscount Alanbrooke

Alan Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke

Field Marshal The Rt. Hon. Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, KG, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO & Bar , was a senior commander in the British Army. He was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff during the Second World War, and was promoted to Field Marshal in 1944...

), and Earl Marshal

Earl Marshal

Earl Marshal is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England...

of the United Kingdom (the Duke of Norfolk

Bernard Fitzalan-Howard, 16th Duke of Norfolk

Bernard Marmaduke Fitzalan-Howard, 16th Duke of Norfolk, , styled Earl of Arundel and Surrey until 1917, was the eldest surviving son of Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, who died when Bernard was only 9 years old...

), all led by the Garter Principal King of Arms

Garter Principal King of Arms

The Garter Principal King of Arms is the senior King of Arms, and the senior Officer of Arms of the College of Arms. He is therefore the most powerful herald within the jurisdiction of the College – primarily England, Wales and Northern Ireland – and so arguably the most powerful in the world...

(George Bellew

George Bellew

Sir George Rothe Bellew, KCB, KCVO, KStJ, FSA was a long-serving officer of arms at the College of Arms is London. An expert genealogist and armorist, Bellew was appointed to the office of Garter Principal King of Arms–the highest heraldic office in England and Wales.-Personal life:Bellew...

), asked the audience in each direction of the compass separately: "Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Elizabeth, your undoubted Queen: wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?" The crowd would reply "God save Queen Elizabeth," every time, to each of which the Queen would curtsey in return.

Seated again on the Chair of Estate, Elizabeth then took the coronation Oath as administered by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the lengthy oath, the Queen swore to govern each of her countries according to their respective laws and customs, to mete out law and justice with mercy, to uphold Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

in the United Kingdom and protect the Church of England and preserve its bishops and clergy. She proceeded to the altar where she stated "The things which I have here promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God," before kissing the Bible and putting the royal sign-manual

Royal sign-manual

The royal sign manual is the formal name given in the Commonwealth realms to the autograph signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive actfor example, an...

to the oath as the Bible was returned to the Dean of Westminster. From him the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The Moderator of the General Assembly of Church of Scotland is a Minister, Elder or Deacon of the Church of Scotland chosen to "moderate" the annual General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, which is held for a week in Edinburgh every May....

, James Pitt-Watson, took the Bible and presented it to the Queen again, saying "to keep your Majesty ever mindful of the law and the Gospel of God... we present you with this Book"; Elizabeth returned the book to Pitt-Watson, who placed it back with the Dean of Westminster.

The communion

Communion (Christian)

The term communion is derived from Latin communio . The corresponding term in Greek is κοινωνία, which is often translated as "fellowship". In Christianity, the basic meaning of the term communion is an especially close relationship of Christians, as individuals or as a Church, with God and with...

service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace," before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter

First Epistle of Peter

The First Epistle of Peter, usually referred to simply as First Peter and often written 1 Peter, is a book of the New Testament. The author claims to be Saint Peter the apostle, and the epistle was traditionally held to have been written during his time as bishop of Rome or Bishop of Antioch,...

, Psalms, and the Gospel of Matthew

Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel According to Matthew is one of the four canonical gospels, one of the three synoptic gospels, and the first book of the New Testament. It tells of the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth...

. Elizabeth was then anointed

Anointing

To anoint is to pour or smear with perfumed oil, milk, water, melted butter or other substances, a process employed ritually by many religions. People and things are anointed to symbolize the introduction of a sacramental or divine influence, a holy emanation, spirit, power or God...

as the assembly sang "Zadok the Priest

Zadok the Priest

Zadok the Priest is a coronation anthem composed by George Frideric Handel using texts from the King James Bible. It is one of the four Coronation Anthems that Handel composed for the coronation of George II of Great Britain in 1727,The other Coronation Anthems Handel composed are: The King Shall...

"; the Queen's jewelry and crimson cape was removed by the Earl of Ancaster and the Mistress of the Robes

Mistress of the Robes

The Mistress of the Robes is the senior lady of the British Royal Household. Formerly responsible for the Queen's clothes and jewellery, the post now has the responsibility for arranging the rota of attendance of the Ladies in Waiting on the Queen, along with various duties at State ceremonies...

, the Duchess of Devonshire

Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire

Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, GCVO, CBE was born Lady Mary Alice Gascoyne-Cecil, daughter of James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury...

, and, wearing only a simple, white linen dress also designed by Hartnell to completely cover the coronation gown, she moved to be seated in the Coronation Chair. There, Fisher, assisted by Don, made a cross on the Queen's forehead with holy oil

Holy anointing oil

The holy anointing oil , formed an integral part of the ordination of the priesthood and the high priest as well as in the consecration of the articles of the tabernacle and subsequent temples in Jerusalem...

made from the same base as that which had been used in the coronation of her father. Because this segment of the ceremony was considered absolutely sacrosanct, it was concealed from the view of the television cameras by a silk canopy held above the Queen by four Knights of the Garter

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, founded in 1348, is the highest order of chivalry, or knighthood, existing in England. The order is dedicated to the image and arms of St...

. When this part of the coronation was complete, and the canopy removed, Don and the Duchess of Devonshire placed on the monarch the Colobium Sindonis

Colobium sindonis

The Colobium sindonis is a simple sleeveless white linen shift worn by monarchs of the United Kingdom during part of the coronation ritual. It symbolizes divesting oneself of all the world's vanity and standing bare before God....

and Supertunica.

From the altar, the Dean of Westminster passed to the Lord Great Chamberlain the spur

Spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids and to back up the natural aids . The spur is used in every equestrian discipline...

s, which were presented to the Queen and then placed back on the altar. The Sword of State was then handed to Elizabeth, who, after a prayer was uttered by Fisher, placed it herself on the altar, and the peer who had been previously holding it took it back again after paying a sum of 100 shillings. The Queen was then invested with the Armills (bracelets), Stole Royal, Robe Royal, and the Sovereign's Orb, followed by the Queen's Ring, the Sceptre with the Cross

Sceptre with the Cross

The Sceptre with the Cross, also known as the St Edward's Sceptre, the Sovereign's Sceptre or the Royal Sceptre, is a sceptre of the British Crown Jewels. It was originally made for the coronation of King Charles II in 1661. In 1905, it was redesigned after the discovery of the Cullinan Diamond...

, and the Sceptre with the Dove

Sceptre with the Dove

The Sceptre with the Dove, also known as the Rod with the Dove or the Rod of Equity and Mercy, is a sceptre of the British Crown Jewels. It was originally made for the coronation of King Charles II in 1661...

. With the first two items on and in her right hand and the latter in her left, Queen Elizabeth was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, with the crowd shouting "God save the Queen!" at the exact moment St. Edward's Crown

St. Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown was one of the English Crown Jewels and remains one of the senior British Crown Jewels, being the official coronation crown used in the coronation of first English, then British, and finally Commonwealth realms monarchs...

touched the monarch's head. The princes and peers gathered then put on their coronets and a 21-gun salute

21-gun salute

Gun salutes are the firing of cannons or firearms as a military or naval honor.The custom stems from naval tradition, where a warship would fire its cannons harmlessly out to sea, until all ammunition was spent, to show that it was disarmed, signifying the lack of hostile intent...

was fired from the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

.

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

The Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester was a soldier and member of the British Royal Family, the third son of George V of the United Kingdom and Queen Mary....

; and Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

The Duke of Kent graduated from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst on 29 July 1955 as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Scots Greys, the beginning of a military career that would last over 20 years. He was promoted to captain on 29 July 1961. The Duke of Kent saw service in Hong Kong from 1962–63...

each proceeded, in order of precedence, to pay their personal homage and allegiance to Elizabeth. When the last baron had completed this task, the assembly shouted "God save Queen Elizabeth. Long live Queen Elizabeth. May the Queen live for ever!" Having removed all her royal regalia, Elizabeth kneeled and took the communion, including a general confession

Confession

This article is for the religious practice of confessing one's sins.Confession is the acknowledgment of sin or wrongs...

and absolution

Absolution

Absolution is a traditional theological term for the forgiveness experienced in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. This concept is found in the Roman Catholic Church, as well as the Eastern Orthodox churches, the Anglican churches, and most Lutheran churches....

, and, along with the audience, recited the Lord's Prayer

Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer is a central prayer in Christianity. In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, it appears in two forms: in the Gospel of Matthew as part of the discourse on ostentation in the Sermon on the Mount, and in the Gospel of Luke, which records Jesus being approached by "one of his...

.

Now wearing the Imperial State Crown and holding the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb, and as the gathered guests sang "God Save the Queen

God Save the Queen

"God Save the Queen" is an anthem used in a number of Commonwealth realms and British Crown Dependencies. The words of the song, like its title, are adapted to the gender of the current monarch, with "King" replacing "Queen", "he" replacing "she", and so forth, when a king reigns...

", Elizabeth left Westminster Abbey through the nave and apse, out the Great West Door, followed by members of the Royal Family, the clergy, her prime ministers, etc. Then, transported back to Buckingham Palace in the Gold State Coach, with an escort of thousands of military personnel from around the Commonwealth, the Queen appeared on the balcony of the Centre Room before a gathered crowd as a flypast

Flypast

Flypast is a term used in the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth, and other countries to denote ceremonial or honorific flights by groups of aircraft and, rarely, by a single aircraft...

went overhead.

Music

The director of music for the coronation was William McKie, organist and master of the choristers at Westminster AbbeyWestminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

. Various pieces, both classical and contemporary, were used throughout the coronation ceremony. Canadian composer Healey Willan

Healey Willan

Healey Willan, was an Anglo-Canadian organist and composer. He composed more than 800 works including operas, symphonies, chamber music, a concerto, and pieces for band, orchestra, organ, and piano...

was commissioned by the Queen to pen an anthem to be played during the homage.

Celebrations, monuments, and media

Coronation chicken

Coronation chicken is a combination of precooked cold chicken meat, herbs and spices, and a creamy mayonnaise-based sauce which can be eaten as a salad or used to fill sandwiches.- Composition :...

was devised, and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment

Victoria Embankment

The Victoria Embankment is part of the Thames Embankment, a road and river walk along the north bank of the River Thames in London. Victoria Embankment extends from the City of Westminster into the City of London.-Construction:...

. Further, street parties were mounted all over the United Kingdom. Two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine Collins Magazine rebranded itself as The Young Elizabethan

The Young Elizabethan

The Young Elizabethan was a British children's literary magazine of the 20th century.The magazine was founded in 1948 as Collins Magazine for Boys & Girls. In 1953, two weeks before the coronation of Elizabeth II, the magazine changed its name to The Young Elizabethan to honour the new queen...

.

On the Korean Peninsula

Korean Peninsula

The Korean Peninsula is a peninsula in East Asia. It extends southwards for about 684 miles from continental Asia into the Pacific Ocean and is surrounded by the Sea of Japan to the south, and the Yellow Sea to the west, the Korea Strait connecting the first two bodies of water.Until the end of...

, Canadian soldiers

Canadian Forces

The Canadian Forces , officially the Canadian Armed Forces , are the unified armed forces of Canada, as constituted by the National Defence Act, which states: "The Canadian Forces are the armed forces of Her Majesty raised by Canada and consist of one Service called the Canadian Armed Forces."...

serving in the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

acknowledged the day by firing blue, red, and white coloured smoke shells at the enemy and drank rum rations in observance. In the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, coronation parties were mounted, one in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

attended by the Queen's uncle and aunt, the Duke

Edward VIII of the United Kingdom

Edward VIII was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, and Emperor of India, from 20 January to 11 December 1936.Before his accession to the throne, Edward was Prince of Wales and Duke of Cornwall and Rothesay...

and Duchess of Windsor, while in Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, military tattoo

Military tattoo

The original meaning of military tattoo is a military drum performance, but nowadays it sometimes means army displays more generally.It dates from the 17th century when the British Army was fighting in the Low Countries...

s, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted. In Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada. Situated in the country's Atlantic region, it incorporates the island of Newfoundland and mainland Labrador with a combined area of . As of April 2011, the province's estimated population is 508,400...

, 90,000 boxes of candy were given to children, some getting theirs delivered by Royal Canadian Air Force

Royal Canadian Air Force

The history of the Royal Canadian Air Force begins in 1920, when the air force was created as the Canadian Air Force . In 1924 the CAF was renamed the Royal Canadian Air Force and granted royal sanction by King George V. The RCAF existed as an independent service until 1968...

drops. In Quebec

Quebec

Quebec or is a province in east-central Canada. It is the only Canadian province with a predominantly French-speaking population and the only one whose sole official language is French at the provincial level....

, 400,000 people turned out in Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

, 100,000 at Jeanne-Mance Park

Jeanne-Mance Park

Jeanne-Mance Park , also known as Fletcher's Field, is an urban park in Montreal, located in the borough of Le Plateau Mont-Royal. It is named after the co-founder of Montreal, Jeanne Mance...

alone. A multicultural

Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is the appreciation, acceptance or promotion of multiple cultures, applied to the demographic make-up of a specific place, usually at the organizational level, e.g...

show was put on at Exhibition Place

Exhibition Place

Exhibition Place is a mixed-use district in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, by the shoreline of Lake Ontario, just west of downtown. The 197–acre area includes expo, trade, and banquet centres, theatre and music buildings, monuments, parkland, sports facilities, and a number of civic, provincial,...

in Toronto

Toronto

Toronto is the provincial capital of Ontario and the largest city in Canada. It is located in Southern Ontario on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. A relatively modern city, Toronto's history dates back to the late-18th century, when its land was first purchased by the British monarchy from...

, square dances and exhibitions took place in the prairie provinces, and, in Vancouver

Vancouver

Vancouver is a coastal seaport city on the mainland of British Columbia, Canada. It is the hub of Greater Vancouver, which, with over 2.3 million residents, is the third most populous metropolitan area in the country,...

, the Chinese community performed a public lion dance

Lion dance

Lion dance is a form of traditional dance in Chinese culture, in which performers mimic a lion's movements in a lion costume. The lion dance is often mistakenly referred to as dragon dance. An easy way to tell the difference is that a lion is operated by two people, while a dragon needs many people...

. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal

Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal

The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal was a commemorative medal made to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.-Issue:For Coronation and Jubilee medals, the practice up until 1977 was that United Kingdom authorities decided on a total number to be produced, then allocated a proportion to...

was presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's countries, and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the UK, commemorative coins were issued. As with the coronation of George VI, acorns shed from oaks in Windsor Great Park

Windsor Great Park

Windsor Great Park is a large deer park of , to the south of the town of Windsor on the border of Berkshire and Surrey in England. The park was, for many centuries, the private hunting ground of Windsor Castle and dates primarily from the mid-13th century...

, around Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a medieval castle and royal residence in Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, notable for its long association with the British royal family and its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I it...

, were shipped around the Commonwealth and planted in parks, schoolyards, cemeteries, and private yards to grow into what are known as Royal Oaks or Coronation Oaks.

News that Edmund Hillary

Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Percival Hillary, KG, ONZ, KBE , was a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer and philanthropist. On 29 May 1953 at the age of 33, he and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers known to have reached the summit of Mount Everest – see Timeline of climbing Mount Everest...

and Tenzing Norgay

Tenzing Norgay

Padma Bhushan, Supradipta-Manyabara-Nepal-Tara Tenzing Norgay, GM born Namgyal Wangdi and often referred to as Sherpa Tenzing, was a Nepalese Sherpa mountaineer...

had reached the summit of Mount Everest

Mount Everest

Mount Everest is the world's highest mountain, with a peak at above sea level. It is located in the Mahalangur section of the Himalayas. The international boundary runs across the precise summit point...

arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen".

The Coronation Cup

Coronation Cup (football)

The Coronation Cup was a one-off football tournament to celebrate the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, between four English and four Scottish clubs, held in Glasgow in May 1953...

football tournament was held at Hampden Park

Hampden Park

Hampden Park is a football stadium in the Mount Florida area of Glasgow, Scotland. The 52,063 capacity venue serves as the national stadium of football in Scotland...

, Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

in May 1953 to mark the Coronation.

See also

- List of participants in Queen Elizabeth II coronation procession

- Proclamation of accession of Elizabeth IIProclamation of accession of Elizabeth IIQueen Elizabeth II was proclaimed sovereign of each of the Commonwealth realms on 6 and 7 February 1952, after the death of her father, King George VI, in the night between 5 February and 6 February, and while the Princess was in Kenya....

- Coronation of the British monarchCoronation of the British monarchThe coronation of the British monarch is a ceremony in which the monarch of the United Kingdom is formally crowned and invested with regalia...

External links

- Newsreel of the coronation from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- Videos of the coronation on YouTube

- The story behind the televising of the Coronation Procession of Queen Elizabeth II

- National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE (archive films of local coronation celebrations throughout Scotland during 1953)