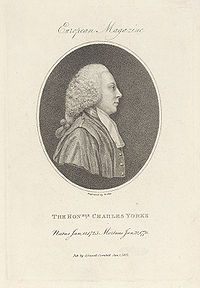

Charles Yorke

Encyclopedia

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

of Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

.

Life

The second son of Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of HardwickePhilip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke

Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke PC was an English lawyer and politician who served as Lord Chancellor. He was a close confidant of the Duke of Newcastle, Prime Minister between 1754 and 1756 and 1757 until 1762....

, he was born in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, and was educated at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. It is notable as the only college founded by Cambridge townspeople: it was established in 1352 by the Guilds of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary...

. His literary abilities were shown at an early age by his collaboration with his brother Philip in the Athenian Letters

Athenian Letters

The Athenian Letters was a collaborative work of Ancient Greek history and geography, published by a circle of authors around Charles Yorke and Philip Yorke, and taking the form of commentary in letter form on Thucidydes...

. In 1745 he published an able treatise on the law of forfeiture

Asset forfeiture

Asset forfeiture is confiscation, by the State, of assets which are either the alleged proceeds of crime or the alleged instrumentalities of crime, and more recently, alleged terrorism. Instrumentalities of crime are property that was allegedly used to facilitate crime, for example cars...

for high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

, in defence of the severe sentence

Sentence (law)

In law, a sentence forms the final explicit act of a judge-ruled process, and also the symbolic principal act connected to his function. The sentence can generally involve a decree of imprisonment, a fine and/or other punishments against a defendant convicted of a crime...

s his father had given to the Scottish

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

Jacobite

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

peers

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

following the Battle of Culloden

Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden was the final confrontation of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. Taking place on 16 April 1746, the battle pitted the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart against an army commanded by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, loyal to the British government...

. In the following year he was called to the bar.

His father being at this time Lord Chancellor, Yorke obtained a sinecure appointment in the Court of Chancery

Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid the slow pace of change and possible harshness of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of...

in 1747, and entered parliament as member for Reigate

Reigate (UK Parliament constituency)

Reigate is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election.-Boundaries:...

, a seat which he afterwards exchanged for that for the University of Cambridge

Cambridge University (UK Parliament constituency)

Cambridge University was a university constituency electing two members to the British House of Commons, from 1603 to 1950.-Boundaries, Electorate and Election Systems:...

. He quickly made his mark in the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, one of his earliest speeches being in favour of his father's reform of the marriage law that led to the Marriage Act 1753

Marriage Act 1753

The Marriage Act 1753, full title "An Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriage", popularly known as Lord Hardwicke's Marriage Act , was the first statutory legislation in England and Wales to require a formal ceremony of marriage. It came into force on 25 March 1754...

.

In 1751 he became counsel to the East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

, and in 1756 he was appointed Solicitor-General

Solicitor General for England and Wales

Her Majesty's Solicitor General for England and Wales, often known as the Solicitor General, is one of the Law Officers of the Crown, and the deputy of the Attorney General, whose duty is to advise the Crown and Cabinet on the law...

, a place which he retained in the administration of the elder Pitt

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham PC was a British Whig statesman who led Britain during the Seven Years' War...

, of whose foreign policy he was a powerful defender.

He resigned with Pitt in 1761, but in 1762 became Attorney-General under Lord Bute

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute KG, PC , styled Lord Mount Stuart before 1723, was a Scottish nobleman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain under George III, and was arguably the last important favourite in British politics...

. He continued to hold this office when George Grenville

George Grenville

George Grenville was a British Whig statesman who rose to the position of Prime Minister of Great Britain. Grenville was born into an influential political family and first entered Parliament in 1741 as an MP for Buckingham...

became Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

(April 1763), and advised the government on the question raised by Wilkes's

John Wilkes

John Wilkes was an English radical, journalist and politician.He was first elected Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fought for the right of voters—rather than the House of Commons—to determine their representatives...

North Briton. Yorke refused to describe the libel as treasonable, while pronouncing it a high misdemeanour. In the following November he resigned office. Resisting Pitt's attempt to draw him into alliance against the ministry he had quit, Yorke maintained, in a speech that extorted the highest eulogy from Horace Walpole, that parliamentary privilege did not extend to cases of libel; though he agreed with Pitt in condemning the principle of general warrants. Yorke, henceforward a member of the Rockingham

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, KG, PC , styled The Hon. Charles Watson-Wentworth before 1733, Viscount Higham between 1733 and 1746, Earl of Malton between 1746 and 1750 and The Earl Malton in 1750, was a British Whig statesman, most notable for his two terms as Prime...

party, was elected recorder of Dover in 1764, and in 1765 he again became Attorney-General in the Rockingham administration, whose policy he did much to shape. He supported the repeal of the Stamp Act

Stamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765 was a direct tax imposed by the British Parliament specifically on the colonies of British America. The act required that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper produced in London, carrying an embossed revenue stamp...

, while urging the simultaneous passing of the Declaratory Act

Declaratory Act

The Declaratory Act was a declaration by the British Parliament in 1766 which accompanied the repeal of the Stamp Act 1765. The government repealed the Stamp Act because boycotts were hurting British trade and used the declaration to justify the repeal and save face...

. His most important measure was the constitution which he drew up for the province of Quebec

Quebec

Quebec or is a province in east-central Canada. It is the only Canadian province with a predominantly French-speaking population and the only one whose sole official language is French at the provincial level....

, and which after his resignation of office became the Quebec Act

Quebec Act

The Quebec Act of 1774 was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain setting procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec...

of 1774.

On the accession to power of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham PC was a British Whig statesman who led Britain during the Seven Years' War...

and Grafton in 1766, Yorke resigned office, and took little part in the debates in parliament during the next four years. In 1770 he was invited by the Duke of Grafton, when Camden was dismissed from the Chancellorship

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

, to take his seat on the woolsack. He had, however, explicitly pledged himself to Rockingham and his party not to take office with Grafton. The King

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

exerted all his personal influence to overcome Yorke's scruples, warning him finally that the Great Seal if now refused would never again be within his grasp. Yorke yielded to the King's entreaty, went to his brother's house, where he met the leaders of the Opposition, and feeling at once overwhelmed with shame, fled to his own house, where three days later he committed suicide (20 January 1770). The patent raising him to the peerage as Baron Morden had been made out, but his last act was to refuse his sanction to the sealing of the document.

Family

Charles Yorke was twice married:Firstly, on 19 May 1755 to Katherine Blount Freeman, with one son:

- Philip YorkePhilip Yorke, 3rd Earl of HardwickePhilip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke KG, PC, FRS , known as Philip Yorke until 1790, was a British politician.-Background and education:...

, (31 May 1757 - 18 Nov 1834) became 3rd Earl of Hardwicke;

Secondly, on 30 December 1762 to Agneta Johnson, with children:

- Charles Philip YorkeCharles Philip YorkeCharles Philip Yorke PC, FRS, FSA , was a British politician. He notably served as Home Secretary from 1803 to 1804.-Background:...

(12 Mar 1764 – 13 Mar 1834) was later to be prominent in government. - Caroline Yorke (29 Aug 1765 – 26 Jul 1818), who married John Eliot, 1st Earl of St GermansJohn Eliot, 1st Earl of St GermansJohn Eliot, 1st Earl of St Germans , known as the Lord Eliot from 1804 to 1815, was a British politician....

. - Joseph Sydney YorkeJoseph Sydney YorkeSir Joseph Sydney Yorke KCB was an officer of the Royal Navy. He served during the American Revolutionary, the French Revolutionary and the Napoleonic Wars, eventually rising to the rank of Admiral.-Family and early life:...

(6 Jun 1768 – 05 May 1831).