Black War

Encyclopedia

The Black War is a term used to describe a period of conflict between British colonists

and Tasmanian Aborigines in the early nineteenth century. Although historians vary on their definition of when the conflict began and ended, it is best understood as the officially sanctioned time of declared martial law

by the colonial government between 1828 and 1832.

The term Black War is also sometimes used to refer to other, later conflicts between European colonists and Aboriginal Australians

on mainland Australia.

Mass killings of Tasmanian Aborigines were reported as having occurred as part of the Black War in Van Diemen's Land

. The accuracy of some of these reports was questioned in the 1830s by the British Government's Commission of Inquiry, headed by Archdeacon (later Bishop) William Broughton and in the 20th century by historian

s, such as N. J. B. Plomley in the 1960s. The controversy has continued, as historian Keith Windschuttle

in 2002 has questioned the accuracy of accounts of massacres and high fatalities.

In combination with epidemic

impacts of introduced Eurasia

n infectious disease

s, to which the Tasmanian Aborigines had no immunity, the conflict had such impact on the Tasmanian Aboriginal population that they were reported to have been exterminated.

Small remnant groups' surviving the Black War were relocated to Bass Strait Islands. Their descendants continue today. Much of their languages, local ecological knowledge, and original cultures are now lost to Tasmania, perhaps with the exception of archaeological records plus historical records made at the time.

. The Black War was one of many conflicts used as an example to define the term genocide as it began to be used in the 1940s.

The use of the term "war" is also sometimes disputed as no official war declaration was made, and only the colonists' side was fully equipped for war. Furthermore, some historians suggest terms such as civil war

, occupation

, murder

or genocide would be more appropriate to describe what happened. Nonetheless, the name Black War has stuck, with the inclusion of the term "war" used loosely.

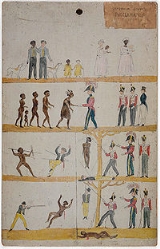

Some date the start of the Black War to the beginning of official European settlement on the island of Tasmania in 1803. The first conflict between colonists and Aborigines was on May 3, 1804. There were three surviving eyewitness accounts of what happened on that day. It is known that a large group of Aborigines, possibly numbering 300 or more, came into the vicinity of the British settlement. The official report by Lt Moore, the commanding officer at the time, referred to an ‘attack’ by Aborigines armed with spears and indicated that two Aborigines were killed and an unknown number wounded. Moore reported having fired a shot from a carronade

(a small cannon) to ‘intimidate’ and disperse the Aborigines but the report does not say whether it fired solid or canister shot

or merely a blank charge meant to frighten. He reported no deaths from the cannon shot, however. The second account, also recorded shortly after the events, was contained in a letter written by the surgeon, Jacob Mountgarrett to Reverend Robert Knopwood. The letter referred to a ‘premeditated’ attack on the settlers in which three Aborigines were killed. In addition to the cannon shot, 2 soldiers fired musket

s in protection of a Risdon Cove settler being beaten on his farm by Aborigines carrying waddies (clubs). These soldiers killed one Aborigine outright, and mortally wounding another who was later found dead in a valley. It is therefore known that in the conflict some Aborigines were killed, and that the colonists "had reason to suppose more were wounded, as one was seen to be taken away bleeding". The conflict apparently arose when the Aborigines discovered that some of the settlers had been hunting kangaroos. It is also known that an infant boy about 2–3 years old was left behind in what was viewed as a "retreat from a hostile attempt made upon the borders of the settlement". The last of the three accounts claimed that "There were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded". This was according to Edward White, an Irish convict present on the scene of the events, speaking before a committee of inquiry in 1830, nearly 30 years later, but just how many he did not know. White, apparently the first to see the approaching Aborigines, also said that "the natives did not threaten me; I was not afraid of them; (they) did not attack the soldiers; they would not have molested them; they had no spears with them; only waddies", though that they had no spears with them is questionable, and his claim needs some qualification. His contemporaries had believed the approach to be a potential attack by a group of Aborigines that greatly outnumbered the colonists in the area, and spoke of "an attack the natives made", their "hostile Appearance", and "that their design was to attack us". White also claimed that the bones of some of the Aborigines were shipped to Sydney in two casks but this claim, like the others he made, is uncorroborated by any other eyewitness. Early Tasmanian history then went on to tell a story of hostilities between colonists and Aborigines, and sporadic and retaliative guerrilla-tactic conflict by the Aborigines in the early years of colonial settlement, usually over food resources, cruel treatment and killing of natives, and the abduction of aboriginal women and children as sexual partners and servants, escalating in the 1820s with the spread of pastoralism.

Others date the conflict to 1826, when the Colonial Times newspaper published an announcement about self-defense reflecting the public mood of the colonists at the time. This was published at a time when relations between Aboriginals and settlers had almost reached the stage of open hostility, a result partly of the usurpation of the natives' hunting grounds, partly of the cruel treatment and killing of natives by shepherds, stockmen, bushrangers and sealers, and partly of the kidnapping of native children. The viewpoint of the settlers seemed to require either the extermination of the Aboriginals or their removal from lands that the settlers wanted to possess.

He ordered what were called “roving parties” to patrol the settled districts and capture Aborigines there, authorising the patrols to shoot any Aborigines who resisted. At the same time, Arthur instructed the military officers and magistrates in the area that the use of arms was to be a last resort.

, to perform a sweep of the area. As in game hunting, over 1000 soldiers and armed civilians swept across the settled districts, moving south and east for several weeks, in an attempt to corral the Aborigines on the Tasman Peninsula

by closing off Eaglehawk Neck, the isthmus

connecting the Tasman peninsula to the rest of the island. Arthur intended to have the Aborigines live together on the peninsula where they could maintain their culture and language. The government and historians consider the Black Line to have been an excessively costly action. It was unsuccessful in capturing more than a few Aborigines. Even though the tribes managed to avoid capture during these events, they were shaken by the size of the campaigns against them, and this brought them to a position whereby they were willing to surrender to George Augustus Robinson and move to Flinders Island.

Largely through the efforts of George Augustus Robinson

Largely through the efforts of George Augustus Robinson

, known as "the Conciliator", by 1833 about 220 Tasmanian Aborigines were persuaded to surrender with assurances that they would be protected and provided for by the government. By August 1834 the Aboriginal problem, as the colonists saw it, had been settled, since all but about a dozen natives had been removed from the mainland to the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island

. Nonetheless, contact with introduced Eurasian diseases continued to reduce their numbers. By 1835 the Aboriginal population had shrunk to fewer than 150 natives, of whom about half were the survivors of those sent by Robinson to Flinders Island. In 1847, the last 47 living inhabitants of Wybalenna were transferred to Oyster Cove, south of Hobart, on the main island of Tasmania.

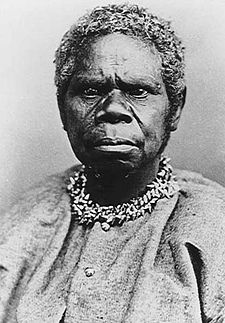

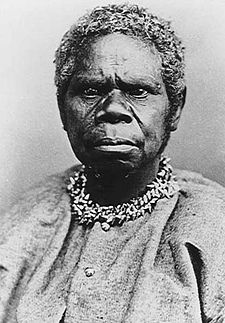

The last full-blooded tribal-born Palawa

from the Oyster Cove community, a woman named Trugernanner (often rendered as Truganini), died in 1876 in Hobart. In an act that disregarded her personhood, and regarded her only as a scientific curiosity, her body was exhumed and her skeleton given to Hobart’s Royal Society Museum which owned it for the next 98 years, even placing it on display until in 1947 public sentiment caused the Museum to take her skeleton down and store it in the basement. In 1976, a century after her death, her skeleton was finally cremated and her ashes scattered by the descendants of her people. In 1997 the Royal Albert Memorial Museum

, Exeter

, returned Trugernanner's necklace and bracelet to Tasmania

. In 2002, some of her hair and skin were found in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England

and returned to Tasmania for burial.

When Trugernanner died, the Tasmanian Government declared the island’s aborigines to be extinct. Its intention was to make everyone understand that the native problem was over, but the government was wrong on both counts. Other aboriginal women born from full-blooded tribal parents outlived her. For example, two indigenous women named Betty and Suke died towards the end of the nineteenth century on Kangaroo Island, off the coast of South Australia, where they had lived most of their lives in the forced company of sealers (though, living on Kangaroo Island, they were not "problems" to the Tasmanian authorities). Fanny Cochrane Smith

, born on the Flinders Island aboriginal settlement, died in 1905 at Port Cygnet, Tasmania. Also the mixed-blood aboriginal community on the Furneaux group of islands continues to constitute a native community until the present day. Nonetheless, Truganini's passing was used to suggest the extinction of Tasmanian Aborigines, and it was taught as fact in schools around the world, and for a long time, even in Tasmania, it was accepted as so.

, Charles Darwin

visited Tasmania in February 1836 and noted in his diary that "The Aboriginal blacks are all removed & kept (in reality as prisoners) in a Promontory, the neck of which is guarded. I believe it was not possible to avoid this cruel step; although without doubt the misconduct of the Whites first led to the Necessity." His Journal and Remarks published in 1839 (now known as The Voyage of the Beagle

) noted that Hobart

town, from the census of 1835, contained 13,826 inhabitants and the whole of Tasmania 36,505. He gave the following account of Tasmania's Black War:

In a later edition he added that "Count Stzelecki states, that 'at the epoch of their deportation in 1835, the number of natives amounted to 210. In 1842, that is, after the interval of seven years, they mustered only 54 individuals; and, while each family of the interior of NSW, uncontaminated by contact with the whites, swarms with children, those of Flinders' Island had during eight years and accession of only 14 in number.'

. Keith Windschuttle

in his 2002 work, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, questioned the historical evidence

used to identify the number of Aborigines killed and the extent of conflict. He stated his belief that it had been exaggerated and challenged what is labelled the "Black armband view of history" of Tasmanian colonisation. His argument in turn has been challenged by a number of authors, for example see "Contra Windschuttle" by S.G. Foster in Quadrant

, March 2003, 47:3.

, in Chapter One of his novel The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, wrote:

This text from H. G. Wells was originally included as one of Microsoft's speech recognition engine training exercises for the user to read out loud into the microphone, but the controversial paragraph at the end was removed in a later version.

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

and Tasmanian Aborigines in the early nineteenth century. Although historians vary on their definition of when the conflict began and ended, it is best understood as the officially sanctioned time of declared martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

by the colonial government between 1828 and 1832.

The term Black War is also sometimes used to refer to other, later conflicts between European colonists and Aboriginal Australians

Australian Aborigines

Australian Aborigines , also called Aboriginal Australians, from the latin ab originem , are people who are indigenous to most of the Australian continentthat is, to mainland Australia and the island of Tasmania...

on mainland Australia.

Mass killings of Tasmanian Aborigines were reported as having occurred as part of the Black War in Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

. The accuracy of some of these reports was questioned in the 1830s by the British Government's Commission of Inquiry, headed by Archdeacon (later Bishop) William Broughton and in the 20th century by historian

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

s, such as N. J. B. Plomley in the 1960s. The controversy has continued, as historian Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle is an Australian writer, historian, and ABC board member, who has authored several books from the 1970s onwards. These include Unemployment, , which analysed the economic causes and social consequences of unemployment in Australia and advocated a socialist response; The Media: a...

in 2002 has questioned the accuracy of accounts of massacres and high fatalities.

In combination with epidemic

Epidemic

In epidemiology, an epidemic , occurs when new cases of a certain disease, in a given human population, and during a given period, substantially exceed what is expected based on recent experience...

impacts of introduced Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

n infectious disease

Infectious disease

Infectious diseases, also known as communicable diseases, contagious diseases or transmissible diseases comprise clinically evident illness resulting from the infection, presence and growth of pathogenic biological agents in an individual host organism...

s, to which the Tasmanian Aborigines had no immunity, the conflict had such impact on the Tasmanian Aboriginal population that they were reported to have been exterminated.

Small remnant groups' surviving the Black War were relocated to Bass Strait Islands. Their descendants continue today. Much of their languages, local ecological knowledge, and original cultures are now lost to Tasmania, perhaps with the exception of archaeological records plus historical records made at the time.

Definition

The descriptions of the Black War differ, ranging from a series of small conflicts and massacres to assertions that the methods used during the conflicts constitute genocideGenocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

. The Black War was one of many conflicts used as an example to define the term genocide as it began to be used in the 1940s.

The use of the term "war" is also sometimes disputed as no official war declaration was made, and only the colonists' side was fully equipped for war. Furthermore, some historians suggest terms such as civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

, occupation

Military occupation

Military occupation occurs when the control and authority over a territory passes to a hostile army. The territory then becomes occupied territory.-Military occupation and the laws of war:...

, murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

or genocide would be more appropriate to describe what happened. Nonetheless, the name Black War has stuck, with the inclusion of the term "war" used loosely.

Details

As the Black War was never officially declared, historians vary in their dating of the extended conflict.Some date the start of the Black War to the beginning of official European settlement on the island of Tasmania in 1803. The first conflict between colonists and Aborigines was on May 3, 1804. There were three surviving eyewitness accounts of what happened on that day. It is known that a large group of Aborigines, possibly numbering 300 or more, came into the vicinity of the British settlement. The official report by Lt Moore, the commanding officer at the time, referred to an ‘attack’ by Aborigines armed with spears and indicated that two Aborigines were killed and an unknown number wounded. Moore reported having fired a shot from a carronade

Carronade

The carronade was a short smoothbore, cast iron cannon, developed for the Royal Navy by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, UK. It was used from the 1770s to the 1850s. Its main function was to serve as a powerful, short-range anti-ship and anti-crew weapon...

(a small cannon) to ‘intimidate’ and disperse the Aborigines but the report does not say whether it fired solid or canister shot

Canister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel ammunition used in cannons. It was similar to the naval grapeshot, but fired smaller and more numerous balls, which did not have to punch through the wooden hull of a ship...

or merely a blank charge meant to frighten. He reported no deaths from the cannon shot, however. The second account, also recorded shortly after the events, was contained in a letter written by the surgeon, Jacob Mountgarrett to Reverend Robert Knopwood. The letter referred to a ‘premeditated’ attack on the settlers in which three Aborigines were killed. In addition to the cannon shot, 2 soldiers fired musket

Musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded, smooth bore long gun, fired from the shoulder. Muskets were designed for use by infantry. A soldier armed with a musket had the designation musketman or musketeer....

s in protection of a Risdon Cove settler being beaten on his farm by Aborigines carrying waddies (clubs). These soldiers killed one Aborigine outright, and mortally wounding another who was later found dead in a valley. It is therefore known that in the conflict some Aborigines were killed, and that the colonists "had reason to suppose more were wounded, as one was seen to be taken away bleeding". The conflict apparently arose when the Aborigines discovered that some of the settlers had been hunting kangaroos. It is also known that an infant boy about 2–3 years old was left behind in what was viewed as a "retreat from a hostile attempt made upon the borders of the settlement". The last of the three accounts claimed that "There were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded". This was according to Edward White, an Irish convict present on the scene of the events, speaking before a committee of inquiry in 1830, nearly 30 years later, but just how many he did not know. White, apparently the first to see the approaching Aborigines, also said that "the natives did not threaten me; I was not afraid of them; (they) did not attack the soldiers; they would not have molested them; they had no spears with them; only waddies", though that they had no spears with them is questionable, and his claim needs some qualification. His contemporaries had believed the approach to be a potential attack by a group of Aborigines that greatly outnumbered the colonists in the area, and spoke of "an attack the natives made", their "hostile Appearance", and "that their design was to attack us". White also claimed that the bones of some of the Aborigines were shipped to Sydney in two casks but this claim, like the others he made, is uncorroborated by any other eyewitness. Early Tasmanian history then went on to tell a story of hostilities between colonists and Aborigines, and sporadic and retaliative guerrilla-tactic conflict by the Aborigines in the early years of colonial settlement, usually over food resources, cruel treatment and killing of natives, and the abduction of aboriginal women and children as sexual partners and servants, escalating in the 1820s with the spread of pastoralism.

Others date the conflict to 1826, when the Colonial Times newspaper published an announcement about self-defense reflecting the public mood of the colonists at the time. This was published at a time when relations between Aboriginals and settlers had almost reached the stage of open hostility, a result partly of the usurpation of the natives' hunting grounds, partly of the cruel treatment and killing of natives by shepherds, stockmen, bushrangers and sealers, and partly of the kidnapping of native children. The viewpoint of the settlers seemed to require either the extermination of the Aboriginals or their removal from lands that the settlers wanted to possess.

Colonial Times self-defence declaration

On December 1, 1826, the Tasmanian Colonial Times declared that:We make no pompous display of Philanthropy. We say this unequivocally SELF DEFENCE IS THE FIRST LAW OF NATURE. THE GOVERNMENT MUST REMOVE THE NATIVES – IF NOT, THEY WILL BE HUNTED DOWN LIKE WILD BEASTS AND DESTROYED!

– Colonial Times and Tasmanian AdvertiserColonial TimesThe Colonial Times was established as the Colonial Times, and Tasmanian Advertiser in 1825 in Hobart, Van Diemen's Land by the former editor of the Hobart Town Gazette, and Van Diemen's Land Advertiser, Andrew Bent...

, 1826

Martial law declaration

Governor Arthur declared martial law in November 1828 in a declaration beginning:"Whereas the Black or Aboriginal Natives of this Island have for a considerable time past, carried on a series of indiscriminate attacks upon the persons and property of divers of His Majesty's subjects: and have especially of late perpetrated most cruel and sanguinary acts of violence and outrage; evincing an evident disposition systematically to kill and destroy the white inhabitants indiscriminately whenever an opportunity of doing so is presented."

He ordered what were called “roving parties” to patrol the settled districts and capture Aborigines there, authorising the patrols to shoot any Aborigines who resisted. At the same time, Arthur instructed the military officers and magistrates in the area that the use of arms was to be a last resort.

Conflict escalation

In February 1830, the government offered a bounty of £5 per adult and £2 per child, for Aborigines captured alive. On 20 August 1830, Governor Arthur's office issued a clarification that rewards were only for Aborigines caught whilst engaged in aggression in the settled districts, and that settlers or convicts who went out and captured “inoffensive Natives in the remote of the remote and unsettled parts of the territory” would not receive a reward. Instead, “If, after the promulgation of this Notice, any wanton attack or aggression against the Natives becomes known to the Government, the offenders will be immediately brought to justice and punished.”Black Line

During the same year, Governor Arthur called upon every able-bodied male colonist, convict or free, to form a human chain, later known as the Black LineBlack Line

The Black Line was an event that occurred in 1830 in Tasmania, or Van Diemen's Land as it was then known. After many years of conflict between British colonists and the Aborigines known as the Black War, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur decided to remove all Aborigines from the settled areas in...

, to perform a sweep of the area. As in game hunting, over 1000 soldiers and armed civilians swept across the settled districts, moving south and east for several weeks, in an attempt to corral the Aborigines on the Tasman Peninsula

Tasman Peninsula

Tasman Peninsula is located around by road south-east of Hobart, at the south east corner of Tasmania, Australia.-Description:The Tasman Peninsula lies south and west of Forestier Peninsula, to which it is connected by an isthmus called Eaglehawk Neck...

by closing off Eaglehawk Neck, the isthmus

Isthmus

An isthmus is a narrow strip of land connecting two larger land areas usually with waterforms on either side.Canals are often built through isthmuses where they may be particularly advantageous to create a shortcut for marine transportation...

connecting the Tasman peninsula to the rest of the island. Arthur intended to have the Aborigines live together on the peninsula where they could maintain their culture and language. The government and historians consider the Black Line to have been an excessively costly action. It was unsuccessful in capturing more than a few Aborigines. Even though the tribes managed to avoid capture during these events, they were shaken by the size of the campaigns against them, and this brought them to a position whereby they were willing to surrender to George Augustus Robinson and move to Flinders Island.

Surrender and relocation

George Augustus Robinson

George Augustus Robinson was a builder and untrained preacher. He was the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Port Phillip District from 1839 to 1849...

, known as "the Conciliator", by 1833 about 220 Tasmanian Aborigines were persuaded to surrender with assurances that they would be protected and provided for by the government. By August 1834 the Aboriginal problem, as the colonists saw it, had been settled, since all but about a dozen natives had been removed from the mainland to the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island

Flinders Island

Flinders Island may refer to:In Australia:* Flinders Island , in the Furneaux Group, is the largest and best known* Flinders Island * Flinders Island , in the Investigator Group* Flinders Island...

. Nonetheless, contact with introduced Eurasian diseases continued to reduce their numbers. By 1835 the Aboriginal population had shrunk to fewer than 150 natives, of whom about half were the survivors of those sent by Robinson to Flinders Island. In 1847, the last 47 living inhabitants of Wybalenna were transferred to Oyster Cove, south of Hobart, on the main island of Tasmania.

The last full-blooded tribal-born Palawa

Palawa

Palawa is a census town in Hazaribag district in the Indian state of Jharkhand.-Demographics: India census, Palawa had a population of 9,757. Males constitute 53% of the population and females 47%. Palawa has an average literacy rate of 60%, higher than the national average of 59.5%. Male literacy...

from the Oyster Cove community, a woman named Trugernanner (often rendered as Truganini), died in 1876 in Hobart. In an act that disregarded her personhood, and regarded her only as a scientific curiosity, her body was exhumed and her skeleton given to Hobart’s Royal Society Museum which owned it for the next 98 years, even placing it on display until in 1947 public sentiment caused the Museum to take her skeleton down and store it in the basement. In 1976, a century after her death, her skeleton was finally cremated and her ashes scattered by the descendants of her people. In 1997 the Royal Albert Memorial Museum

Royal Albert Memorial Museum

Royal Albert Memorial Museum on Queen Street, Exeter, Devon, England is the largest museum in the city.-History:Initially proposed by Sir Stafford Northcote as a practical memorial to Prince Albert, an appeal fund was launched in 1861 and the first phases of the building were completed by 1868...

, Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

, returned Trugernanner's necklace and bracelet to Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

. In 2002, some of her hair and skin were found in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England

Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England is an independent professional body and registered charity committed to promoting and advancing the highest standards of surgical care for patients, regulating surgery, including dentistry, in England and Wales...

and returned to Tasmania for burial.

When Trugernanner died, the Tasmanian Government declared the island’s aborigines to be extinct. Its intention was to make everyone understand that the native problem was over, but the government was wrong on both counts. Other aboriginal women born from full-blooded tribal parents outlived her. For example, two indigenous women named Betty and Suke died towards the end of the nineteenth century on Kangaroo Island, off the coast of South Australia, where they had lived most of their lives in the forced company of sealers (though, living on Kangaroo Island, they were not "problems" to the Tasmanian authorities). Fanny Cochrane Smith

Fanny Cochrane Smith

Fanny Cochrane Smith, was a Tasmanian Aborigine, born in December 1834. She is considered to be the last fluent speaker of a Tasmanian language, and her wax cylinder recordings of songs are the only audio recordings of any of Tasmania's indigenous languages.-Life:Fanny Cochrane's mother and...

, born on the Flinders Island aboriginal settlement, died in 1905 at Port Cygnet, Tasmania. Also the mixed-blood aboriginal community on the Furneaux group of islands continues to constitute a native community until the present day. Nonetheless, Truganini's passing was used to suggest the extinction of Tasmanian Aborigines, and it was taught as fact in schools around the world, and for a long time, even in Tasmania, it was accepted as so.

Charles Darwin's account

During the Beagle survey expeditionSecond voyage of HMS Beagle

The second voyage of HMS Beagle, from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836, was the second survey expedition of HMS Beagle, under captain Robert FitzRoy who had taken over command of the ship on its first voyage after her previous captain committed suicide...

, Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

visited Tasmania in February 1836 and noted in his diary that "The Aboriginal blacks are all removed & kept (in reality as prisoners) in a Promontory, the neck of which is guarded. I believe it was not possible to avoid this cruel step; although without doubt the misconduct of the Whites first led to the Necessity." His Journal and Remarks published in 1839 (now known as The Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle is a title commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his Journal and Remarks, bringing him considerable fame and respect...

) noted that Hobart

Hobart

Hobart is the state capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Founded in 1804 as a penal colony,Hobart is Australia's second oldest capital city after Sydney. In 2009, the city had a greater area population of approximately 212,019. A resident of Hobart is known as...

town, from the census of 1835, contained 13,826 inhabitants and the whole of Tasmania 36,505. He gave the following account of Tasmania's Black War:

In a later edition he added that "Count Stzelecki states, that 'at the epoch of their deportation in 1835, the number of natives amounted to 210. In 1842, that is, after the interval of seven years, they mustered only 54 individuals; and, while each family of the interior of NSW, uncontaminated by contact with the whites, swarms with children, those of Flinders' Island had during eight years and accession of only 14 in number.'

Ongoing historical disputes

The conflict has been a controversial area of study by historians, even characterised as among Australian history warsHistory wars

The history wars in Australia are an ongoing public debate over the interpretation of the history of the British colonisation of Australia and development of contemporary Australian society...

. Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle is an Australian writer, historian, and ABC board member, who has authored several books from the 1970s onwards. These include Unemployment, , which analysed the economic causes and social consequences of unemployment in Australia and advocated a socialist response; The Media: a...

in his 2002 work, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, questioned the historical evidence

Historiography

Historiography refers either to the study of the history and methodology of history as a discipline, or to a body of historical work on a specialized topic...

used to identify the number of Aborigines killed and the extent of conflict. He stated his belief that it had been exaggerated and challenged what is labelled the "Black armband view of history" of Tasmanian colonisation. His argument in turn has been challenged by a number of authors, for example see "Contra Windschuttle" by S.G. Foster in Quadrant

Quadrant (magazine)

Quadrant is an Australian literary and cultural journal. The magazine takes a conservative position on political and social issues, describing itself as sceptical of 'unthinking Leftism, or political correctness, and its "smelly little orthodoxies"'. Quadrant reviews literature, as well as...

, March 2003, 47:3.

Literary references

H. G. WellsH. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells was an English author, now best known for his work in the science fiction genre. He was also a prolific writer in many other genres, including contemporary novels, history, politics and social commentary, even writing text books and rules for war games...

, in Chapter One of his novel The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, wrote:

- "We must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals such as the vanished bisonBisonMembers of the genus Bison are large, even-toed ungulates within the subfamily Bovinae. Two extant and four extinct species are recognized...

and dodoDodoThe dodo was a flightless bird endemic to the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. Related to pigeons and doves, it stood about a meter tall, weighing about , living on fruit, and nesting on the ground....

, but also upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years."

This text from H. G. Wells was originally included as one of Microsoft's speech recognition engine training exercises for the user to read out loud into the microphone, but the controversial paragraph at the end was removed in a later version.

See also

- History warsHistory warsThe history wars in Australia are an ongoing public debate over the interpretation of the history of the British colonisation of Australia and development of contemporary Australian society...

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Tasmanian AboriginesTasmanian AboriginesThe Tasmanian Aborigines were the indigenous people of the island state of Tasmania, Australia. Before British colonisation in 1803, there were an estimated 3,000–15,000 Parlevar. A number of historians point to introduced disease as the major cause of the destruction of the full-blooded...

- Trugernanner & Fanny Cochrane SmithFanny Cochrane SmithFanny Cochrane Smith, was a Tasmanian Aborigine, born in December 1834. She is considered to be the last fluent speaker of a Tasmanian language, and her wax cylinder recordings of songs are the only audio recordings of any of Tasmania's indigenous languages.-Life:Fanny Cochrane's mother and...

External links

- Extract from James Bonwick, Black War of Van Diemen’s Land, London, pp. 154–155 Accessed 15 August 2009