Australia-New Zealand relations

Encyclopedia

Trans-Tasman

Trans-Tasman is an adjective used primarily in Australia and New Zealand, which signifies an interrelationship between both countries. Its name originates from the Tasman Sea which lies between the two countries...

relations due to the countries being on opposite sides of the Tasman Sea

Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea is the large body of water between Australia and New Zealand, approximately across. It extends 2,800 km from north to south. It is a south-western segment of the South Pacific Ocean. The sea was named after the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman, the first recorded European...

, are extremely close with both sharing British colonial heritage and being part of the Anglosphere

Anglosphere

Anglosphere is a neologism which refers to those nations with English as the most common language. The term can be used more specifically to refer to those nations which share certain characteristics within their cultures based on a linguistic heritage, through being former British colonies...

. New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

sent representatives to the constitutional conventions

Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia formed one nation...

which led to the uniting of the six Australian colonies

States and territories of Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia is a union of six states and various territories. The Australian mainland is made up of five states and three territories, with the sixth state of Tasmania being made up of islands. In addition there are six island territories, known as external territories, and a...

but opted not to join; still, in the Boer War and in World War I and World War II, soldiers from New Zealand

New Zealand Defence Force

The New Zealand Defence Force consists of three services: the Royal New Zealand Navy; the New Zealand Army; and the Royal New Zealand Air Force. The Commander-in-Chief of the NZDF is His Excellency Rt. Hon...

fought alongside Australians

Australian Defence Force

The Australian Defence Force is the military organisation responsible for the defence of Australia. It consists of the Royal Australian Navy , Australian Army, Royal Australian Air Force and a number of 'tri-service' units...

in the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force that was formed in Egypt in 1915 and operated during the Battle of Gallipoli. General William Birdwood commanded the corps, which comprised troops from the First Australian Imperial...

. In recent years the Closer Economic Relations

Closer Economic Relations

Closer Economic Relations is a free trade agreement between the governments of New Zealand and Australia. It is also known as the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement and sometimes shortened to...

free trade agreement and its predecessors have inspired everconverging economic integration

Economic integration

Economic integration refers to trade unification between different states by the partial or full abolishing of customs tariffs on trade taking place within the borders of each state...

. The culture of Australia

Culture of Australia

The culture of Australia is essentially a Western culture influenced by the unique geography of the Australian continent and by the diverse input of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and various waves of multi-ethnic migration which followed the British colonisation of Australia...

does differ from the culture of New Zealand

Culture of New Zealand

The culture of New Zealand is largely inherited from British and European custom, interwoven with Maori and Polynesian tradition. An isolated Pacific Island nation, New Zealand was comparatively recently settled by humans...

and there are sometimes differences of opinion which some have declared as symptomatic of sibling rivalry

Sibling rivalry

Sibling rivalry is a type of competition or animosity among children, blood-related or not.Siblings generally spend more time together during childhood than they do with parents. The sibling bond is often complicated and is influenced by factors such as parental treatment, birth order, personality,...

. This often centres upon sports such as rugby union or cricket or in commercial tensions such as those arising from the failure of Ansett Australia

Ansett Australia

Ansett Australia, Ansett, Ansett Airlines of Australia, or ANSETT-ANA as it was commonly known in earlier years, was a major Australian airline group, based in Melbourne. The airlines flew domestically within Australia and to destinations in Asia during its operation in 1996...

or those engendered by the formerly long-standing Australian ban on New Zealand apple imports.

Both countries are Commonwealth realm

Commonwealth Realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state within the Commonwealth of Nations that has Elizabeth II as its monarch and head of state. The sixteen current realms have a combined land area of 18.8 million km² , and a population of 134 million, of which all, except about two million, live in the six...

s sharing the Head of the Commonwealth

Head of the Commonwealth

The Head of the Commonwealth heads the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation which currently comprises 54 sovereign states. The position is currently occupied by the individual who serves as monarch of each of the Commonwealth realms, but has no day-to-day involvement in the...

as Head of State

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

in universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

supported systems of Westminster

Westminster System

The Westminster system is a democratic parliamentary system of government modelled after the politics of the United Kingdom. This term comes from the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the Parliament of the United Kingdom....

representative

Representative democracy

Representative democracy is a form of government founded on the principle of elected individuals representing the people, as opposed to autocracy and direct democracy...

parliamentary democracy within a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

. Their only land border defines the western extent of the Ross Dependency

Ross Dependency

The Ross Dependency is a region of Antarctica defined by a sector originating at the South Pole, passing along longitudes 160° east to 150° west, and terminating at latitude 60° south...

and eastern extent of the Australian Antarctic Territory

Australian Antarctic Territory

The Australian Antarctic Territory is a part of Antarctica. It was claimed by the United Kingdom and placed under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1933. It is the largest territory of Antarctica claimed by any nation...

. They acknowledge two distinct maritime boundaries

Maritime boundary

Maritime boundary is a conceptual means of division of the water surface of the planet into maritime areas that are defined through surrounding physical geography or by human geography. As such it usually includes areas of exclusive national rights over the mineral and biological resources,...

conclusively delimited

Boundary delimitation

Boundary delimitation, or simply delimitation, is the term used to describe the drawing of boundaries, but is most often used to describe the drawing of electoral boundaries, specifically those of precincts, states, counties or other municipalities...

by the Australia – New Zealand Maritime Treaty of 2004

Australia – New Zealand Maritime Treaty

The Australia – New Zealand Maritime Treaty is a 2004 treaty between Australia and New Zealand in which the two countries formally delimited the maritime boundary between the two countries....

.

History

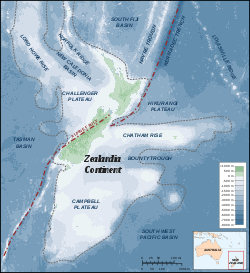

Zealandia (continent)

Zealandia , also known as Tasmantis or the New Zealand continent, is a nearly submerged continental fragment that sank after breaking away from Australia 60–85 million years ago, having separated from Antarctica between 85 and 130 million years ago...

, of which present day New Zealand represents the largest unsubmerged part, probably separated from Antarctica between 130 and 85 million years ago and then from the separate continent of Australia 60–85 million years ago in the break-up of East Gondwana

Gondwana

In paleogeography, Gondwana , originally Gondwanaland, was the southernmost of two supercontinents that later became parts of the Pangaea supercontinent. It existed from approximately 510 to 180 million years ago . Gondwana is believed to have sutured between ca. 570 and 510 Mya,...

occurring in the Cretaceous

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous , derived from the Latin "creta" , usually abbreviated K for its German translation Kreide , is a geologic period and system from circa to million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the...

and early Paleogene

Paleogene

The Paleogene is a geologic period and system that began 65.5 ± 0.3 and ended 23.03 ± 0.05 million years ago and comprises the first part of the Cenozoic Era...

geologic periods. Zealandia and Australia together are part of the wider regions known as Oceania

Oceania

Oceania is a region centered on the islands of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Conceptions of what constitutes Oceania range from the coral atolls and volcanic islands of the South Pacific to the entire insular region between Asia and the Americas, including Australasia and the Malay Archipelago...

and Australasia

Australasia

Australasia is a region of Oceania comprising Australia, New Zealand, the island of New Guinea, and neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term was coined by Charles de Brosses in Histoire des navigations aux terres australes...

. Australia, New Zealand's North Island

North Island

The North Island is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the much less populous South Island by Cook Strait. The island is in area, making it the world's 14th-largest island...

and the northwest of the South Island

South Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

are on the Indo-Australian Plate

Indo-Australian Plate

The Indo-Australian Plate is a major tectonic plate that includes the continent of Australia and surrounding ocean, and extends northwest to include the Indian subcontinent and adjacent waters...

, with the remainder of the South Island on the Pacific Plate

Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At 103 million square kilometres, it is the largest tectonic plate....

.

The history of indigenous Australians

History of Indigenous Australians

The history of Indigenous Australians is thought to have spanned 40 000 to 45 000 years, although some estimates have put the figure at up to 80 000 years before European settlement...

on their own continent is generally thought to be rich to the extent of at least 40,000–45,000 years duration, whereas Polynesian

Polynesians

The Polynesian peoples is a grouping of various ethnic groups that speak Polynesian languages, a branch of the Oceanic languages within the Austronesian languages, and inhabit Polynesia. They number approximately 1,500,000 people...

Maori arrived in Aotearoa

Aotearoa

Aotearoa is the most widely known and accepted Māori name for New Zealand. It is used by both Māori and non-Māori, and is becoming increasingly widespread in the bilingual names of national organisations, such as the National Library of New Zealand / Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa.-Translation:The...

/New Zealand in several waves by means of waka

Waka (canoe)

Waka are Māori watercraft, usually canoes ranging in size from small, unornamented canoes used for fishing and river travel, to large decorated war canoes up to long...

some time before 1300. Australoid

Australoid

The Australoid race is a broad racial classification. The concept originated with a typological method of racial classification. They were described as having dark skin with wavy hair, in the case of Veddoids from South Asia and Aboriginal Australians, or hair ranging from straight to kinky in the...

indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. The Aboriginal Indigenous Australians migrated from the Indian continent around 75,000 to 100,000 years ago....

and Polynesian Maori indigenous to New Zealand are not recorded to have met or interacted prior to 17th and 18th century European exploration of Australia

European exploration of Australia

The European exploration of Australia encompasses several waves of seafarers and land explorers. Although Australia is often loosely said to have been discovered by Royal Navy Lieutenant James Cook in 1770, he was merely one of a number of European explorers to have sighted and landed on the...

. Regarding the respective indigenous populations, while it may be said that there is a single Maori language

Maori language

Māori or te reo Māori , commonly te reo , is the language of the indigenous population of New Zealand, the Māori. It has the status of an official language in New Zealand...

and the iwi

Iwi

In New Zealand society, iwi form the largest everyday social units in Māori culture. The word iwi means "'peoples' or 'nations'. In "the work of European writers which treat iwi and hapū as parts of a hierarchical structure", it has been used to mean "tribe" , or confederation of tribes,...

have been able to present as a unified population represented by a monarch

Maori King Movement

The Māori King Movement or Kīngitanga is a movement that arose among some of the Māori tribes of New Zealand in the central North Island ,in the 1850s, to establish a role similar in status to that of the monarch of the colonising people, the British, as a way of halting the alienation of Māori land...

neither has ever been able to be said of the Australian aboriginal languages or their corresponding population groups.

The first European landing on the Australian continent occurred in the Janszoon voyage of 1606

Janszoon voyage of 1606

Willem Janszoon made the first recorded European landing on the Australian continent in 1606, sailing from Bantam, Java in the Duyfken. As an employee of the Dutch East India Company, Janszoon had been instructed to explore the coast of New Guinea in search of economic opportunities...

. Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

in two distinct voyages in the period 1642–1644 is recorded as the first person to have coastally explored regions of the respective landform

Landform

A landform or physical feature in the earth sciences and geology sub-fields, comprises a geomorphological unit, and is largely defined by its surface form and location in the landscape, as part of the terrain, and as such, is typically an element of topography...

s including Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

– later named for him as the Australian state of Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

. The first voyage of James Cook

First voyage of James Cook

The first voyage of James Cook was a combined Royal Navy and Royal Society expedition to the south Pacific ocean aboard HMS Endeavour, from 1768 to 1771...

stands as significant for the circumnavigation

Circumnavigation

Circumnavigation – literally, "navigation of a circumference" – refers to travelling all the way around an island, a continent, or the entire planet Earth.- Global circumnavigation :...

of New Zealand in 1769 and as the European discovery and first ever coastal navigation of Eastern Australia from April to August 1770

Australian places named by James Cook

This is a list of Australian places named by James Cook. James Cook was the first explorer to chart most of the eastern Australian coast, one of the last major coastlines in the world unknown to Europeans at the time...

. The European settlement of Australia and New Zealand, then referred to as the colony of New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

, dates from the arrival of the First Fleet

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

into Cadi

Cadigal

The Cadigal, also spelled as Gadigal, are a group of Aboriginal Australians who originally inhabited the area that they called 'Cadi', part of which later became known as the Marrickville Local Government Area of Sydney. Cadigal territory lies south of Port Jackson and stretches from South Head to...

/Port Jackson

Port Jackson

Port Jackson, containing Sydney Harbour, is the natural harbour of Sydney, Australia. It is known for its beauty, and in particular, as the location of the Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge...

on Australia Day

Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia...

, 1788. New Zealand was formed as a new colony out of the territory of New South Wales in 1840, at which time its pakeha

Pakeha

Pākehā is a Māori language word for New Zealanders who are "of European descent". They are mostly descended from British and to a lesser extent Irish settlers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although some Pākehā have Dutch, Scandinavian, German, Yugoslav or other ancestry...

population number about 2000 descended from Christian missionaries, sealers, and whalers

Whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales mainly for meat and oil. Its earliest forms date to at least 3000 BC. Various coastal communities have long histories of sustenance whaling and harvesting beached whales...

.

Penal colony

A penal colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general populace by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory...

, neither were some of the Australian colonies. In particular, South Australia

South Australia

South Australia is a state of Australia in the southern central part of the country. It covers some of the most arid parts of the continent; with a total land area of , it is the fourth largest of Australia's six states and two territories.South Australia shares borders with all of the mainland...

was founded and settled in a similar manner to New Zealand, both being influenced by the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield was a British politician, the driving force behind much of the early colonisation of South Australia, and later New Zealand....

.

Both countries experienced ongoing internal conflict concerning indigenous and settler populations, although this conflict took very different forms most sharply manifested in the New Zealand land wars

New Zealand land wars

The New Zealand Wars, sometimes called the Land Wars and also once called the Māori Wars, were a series of armed conflicts that took place in New Zealand between 1845 and 1872...

and Australian frontier wars

Australian frontier wars

The Australian frontier wars were a series of conflicts fought between Indigenous Australians and European settlers. The first fighting took place in May 1788 and the last clashes occurred in the early 1930s. Indigenous fatalities from the fighting have been estimated as at least 20,000 and...

respectively. Whereas Maori iwi endured the Musket Wars

Musket Wars

The Musket Wars were a series of five hundred or more battles mainly fought between various hapū , sometimes alliances of pan-hapū groups and less often larger iwi of Māori between 1807 and 1842, in New Zealand.Northern tribes such as the rivals Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Whātua were the first to obtain...

of the period 1807-1839 preceding the former in New Zealand, indigenous Australians have no comparable period of the experience of warfare amongst each other employing European-introduced modern weaponry

Military technology

Military technology is the collection of equipment, vehicles, structures and communication systems that are designed for use in warfare. It comprises the kinds of technology that are distinctly military in nature and not civilian in application, usually because they are impractical in civilian...

either before or after their own confrontations with European settler society. Both countries experienced nineteenth century gold rushes

Australian gold rushes

The Australian gold rush started in 1851 when prospector Edward Hammond Hargraves claimed the discovery of payable gold near Bathurst, New South Wales, at a site Edward Hargraves called Ophir.Eight months later, gold was found in Victoria...

and during the nineteenth century there was extensive trade and travel between the colonies

Crown colony

A Crown colony, also known in the 17th century as royal colony, was a type of colonial administration of the English and later British Empire....

.

Federal Council of Australasia

The Federal Council of Australasia was a forerunner to the current Commonwealth of Australia, though its structure and members were different. It consisted of the then British colonies of New Zealand, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, Fiji, and others. However, the largest colony in the region,...

from 1885 and fully involved itself among the other selfgoverning colonies

Self-governing colony

A self-governing colony is a colony with an elected legislature, in which politicians are able to make most decisions without reference to the colonial power with formal or nominal control of the colony...

in the 1890 conference and 1891 Convention leading up to Federation of Australia

Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia formed one nation...

. Ultimately it declined to accept the invitation to join the Commonwealth of Australia resultingly formed in 1901, remaining as a self-governing colony

Self-governing colony

A self-governing colony is a colony with an elected legislature, in which politicians are able to make most decisions without reference to the colonial power with formal or nominal control of the colony...

until becoming the Dominion of New Zealand

Dominion of New Zealand

The Dominion of New Zealand is the former name of the Realm of New Zealand.Originally administered from New South Wales, New Zealand became a direct British colony in 1841 and received a large measure of self-government following the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852...

in 1907 and with other territories later constituting the Realm of New Zealand

Realm of New Zealand

The Realm of New Zealand is the entire area in which the Queen in right of New Zealand is head of state. The Realm comprises New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau and the Ross Dependency in Antarctica, and is defined by a 1983 Letters Patent constituting the office of Governor-General of New...

effectively as an independent country of its own

Independence of New Zealand

The independence of New Zealand is a matter of continued academic and social debate. New Zealand has no fixed date of independence, instead independence came about as a result of New Zealand's evolving constitutional status. New Zealand evolved as one of the British Dominions, colonies within the...

. In the 1908 Olympics, the 1911 Festival of Empire

Festival of Empire

The Festival of Empire or Festival of the Empire was held at The Crystal Palace in London in 1911, to celebrate the coronation of King George V...

and the 1912 Olympics

1912 Summer Olympics

The 1912 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the V Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event held in Stockholm, Sweden, between 5 May and 27 July 1912. Twenty-eight nations and 2,407 competitors, including 48 women, competed in 102 events in 14 sports...

the two countries were represented at least in sporting competition as the unified entity "Australasia

Australasia

Australasia is a region of Oceania comprising Australia, New Zealand, the island of New Guinea, and neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term was coined by Charles de Brosses in Histoire des navigations aux terres australes...

".

Both continued to co-operate politically in the 20th century as each sought closer relations with the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, particularly in the area of trade. This was helped by the development of refrigerated shipping, which allowed New Zealand in particular to base its economy on the export of meat and dairy – both of which Australia had in abundance – to Britain.

The two nations sealed the Canberra Pact

Canberra Pact

The Canberra Pact was a treaty of mutual defense between the governments of Australia and New Zealand, signed on 21 January 1944. This Pact was not a military alliance; its focus was on working together on issues of mutual interest. New Zealand and Australia signed the pact so they could have a...

in January 1944 for the purpose of successfully prosecuting war against the Axis Powers

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

in World War II and providing for the administration of an armistice

Armistice

An armistice is a situation in a war where the warring parties agree to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, but may be just a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace...

and territorial trusteeship

United Nations Trusteeship Council

The United Nations Trusteeship Council, one of the principal organs of the United Nations, was established to help ensure that trust territories were administered in the best interests of their inhabitants and of international peace and security...

in its aftermath. The Agreement foreshadowed the establishment of a permanent Australia-New Zealand Secretariat, it provided for consultation in matters of common interest, it provided for the maintenance of separate military commands and for "the maximum degree of unity in the presentation .. of the views of the two countries".

The quantity of trans-Tasman trade increased by 9% per annum from the early 1980s through to the end of 2007, with the Closer Economic Relations

Closer Economic Relations

Closer Economic Relations is a free trade agreement between the governments of New Zealand and Australia. It is also known as the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement and sometimes shortened to...

free trade agreement of 1983 being a major turning point. This was partially a result of Britain joining the European Economic Community

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community The European Economic Community (EEC) The European Economic Community (EEC) (also known as the Common Market in the English-speaking world, renamed the European Community (EC) in 1993The information in this article primarily covers the EEC's time as an independent...

in the early 1970s, thus restricting the access of both countries to their biggest export market.

Military

In the Harriet Affair of 1834, a group of British soldiers of the 50th Regiment from Australia landed in TaranakiTaranaki

Taranaki is a region in the west of New Zealand's North Island and is the 10th largest region of New Zealand by population. It is named for the region's main geographical feature, Mount Taranaki....

, New Zealand, to rescue the wife and children of John (Jacky) Guard

John Guard

John 'Jacky' Guard was an English convict sent to Australia who was one of the first European settlers in the South Island of New Zealand, working as a whaler and trader.-Early life:...

and punish the kidnappers - the first clash between Māori and British troops. The expedition was sent by Governor Bourke from Sydney and was subsequently criticized for use of excessive force by a British House of Commons report in 1835.

In 1861, the Australian ship HMCSS Victoria

HMS Victoria (1855)

HMVS Victoria was a 580-ton combined steam/sail sloop-of-war built in England in the 1850s for the colony of Victoria, Australia....

was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki

First Taranaki War

The First Taranaki War was an armed conflict over land ownership and sovereignty that took place between Māori and the New Zealand Government in the Taranaki district of New Zealand's North Island from March 1860 to March 1861....

. Victoria was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications. In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the invasion of the Waikato

Invasion of the Waikato

The Invasion of Waikato or Kingitanga Suppression Movement was a campaign during the middle stages of the New Zealand Wars, fought in the North Island of New Zealand from July 1863 to April 1864 between the military forces of the Colonial Government and a federation of Māori tribes known as the...

. Promised settlement on confiscated land, more than 2500 Australians were recruited. Other Australians became scouts in the Company of Forest Rangers. Australians were involved in actions at Matarikoriko, Pukekohe East

Defence of Pukekohe East 1863

The Defence of Pukekohe East was an action during theInvasion of the Waikato, part of the New Zealand Wars. On 13 September and 14 September 1863, 11 settlers and 6 militia men inside a half completed stockade around the Pukekohe East church held off a Māori taua or war party of approximately 200...

, Titi Hill, Orakau and Te Ranga.

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

and both either sent soldiers or permitted the sending of military volunteer

Military volunteer

A military volunteer is a person who enlists in military service by free will, and is not a mercenary or a foreign legionaire. Volunteers often enlist to fight in the armed forces of a foreign country. Military volunteers are essential for the operation of volunteer militaries.Many armies,...

s to the Mahdist War

Mahdist War

The Mahdist War was a colonial war of the late 19th century. It was fought between the Mahdist Sudanese and the Egyptian and later British forces. It has also been called the Anglo-Sudan War or the Sudanese Mahdist Revolt. The British have called their part in the conflict the Sudan Campaign...

in the Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

, the quelling of the Boxer Rebellion

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also called the Boxer Uprising by some historians or the Righteous Harmony Society Movement in northern China, was a proto-nationalist movement by the "Righteous Harmony Society" , or "Righteous Fists of Harmony" or "Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists" , in China between...

, the Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

, the First and Second World War

World war

A world war is a war affecting the majority of the world's most powerful and populous nations. World wars span multiple countries on multiple continents, with battles fought in multiple theaters....

s and the Malayan Emergency

Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency was a guerrilla war fought between Commonwealth armed forces and the Malayan National Liberation Army , the military arm of the Malayan Communist Party, from 1948 to 1960....

and Konfrontasi. Independent of the sense of Empire (or Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

), both nations in the second half of the twentieth century otherwise provided contingents in support of US strategic aims in the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

, Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

, and Gulf War

Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War , commonly referred to as simply the Gulf War, was a war waged by a U.N.-authorized coalition force from 34 nations led by the United States, against Iraq in response to Iraq's invasion and annexation of Kuwait.The war is also known under other names, such as the First Gulf...

. Whereas military personnel from both countries participated in UNTSO, the Multinational Force and Observers

Multinational Force and Observers

The Multinational Force and Observers is an international peacekeeping force overseeing the terms of the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel.-Background:...

to Sinai, INTERFET

INTERFET

The International Force for East Timor was a multinational peacekeeping taskforce, mandated by the United Nations to address the humanitarian and security crisis which took place in East Timor from 1999–2000 until the arrival of United Nations peacekeepers...

to East Timor

East Timor

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, commonly known as East Timor , is a state in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the nearby islands of Atauro and Jaco, and Oecusse, an exclave on the northwestern side of the island, within Indonesian West Timor...

, the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, UNMIS to Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

, and more recent intervention in Tonga the New Zealand government officially condemned the 2003 invasion of Iraq

2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq , was the start of the conflict known as the Iraq War, or Operation Iraqi Freedom, in which a combined force of troops from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Poland invaded Iraq and toppled the regime of Saddam Hussein in 21 days of major combat operations...

and stood apart from Australia in refusing to contribute any combat forces. Somewhat similarly in 1982, although without speaking in condemnation, Australia found no purpose in joining with New Zealand to support the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

in the Falklands War

Falklands War

The Falklands War , also called the Falklands Conflict or Falklands Crisis, was fought in 1982 between Argentina and the United Kingdom over the disputed Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands...

against Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

just as New Zealand had declined to join Australia in Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention was a multi-national military expedition launched in 1918 during World War I which continued into the Russian Civil War. Its operations included forces from 14 nations and were conducted over a vast territory...

or in UNEF

United Nations Emergency Force

The first United Nations Emergency Force was established by United Nations General Assembly to secure an end to the 1956 Suez Crisis with resolution 1001 on November 7, 1956. The force was developed in large measure as a result of efforts by UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and a proposal...

to Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

during the 1970s.

In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force that was formed in Egypt in 1915 and operated during the Battle of Gallipoli. General William Birdwood commanded the corps, which comprised troops from the First Australian Imperial...

(ANZACs). Together Australia and New Zealand saw their first major military action in the Battle of Gallipoli

Battle of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

, in which both suffered major casualties. For many decades the battle was seen by both countries as the moment at which they came of age as nations. It continues to be commemorated annually in both countries on Anzac Day

ANZAC Day

Anzac Day is a national day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand, commemorated by both countries on 25 April every year to honour the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who fought at Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. It now more broadly commemorates all...

, although since the 1960s there has been some questioning of the "coming of age" idea.

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain. Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it was directly targeted by the Empire of Japan, with Darwin bombed and Broome attacked

Attack on Broome

The town of Broome, Western Australia was attacked by Japanese fighter planes on 3 March 1942, during World War II. At least 88 people were killed....

. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the ANZUS

ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty is the military alliance which binds Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States to cooperate on defence matters in the Pacific Ocean area, though today the treaty is understood to relate to attacks...

pact of 1951, in which Australia, New Zealand and the United States agreed to defend each other in the event of enemy attack. Although no such attack occurred until, arguably, 11 September 2001, Australia and New Zealand both contributed troops to the Korean

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

and Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

s. Australia's contribution to the Vietnam War

Military history of Australia during the Vietnam War

Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War began as a small commitment of 30 men in 1962, and increased over the following decade to a peak of 7,672 Australians deployed in South Vietnam or in support of Australian forces there. The Vietnam War was the longest and most controversial war Australia...

in particular was much larger than New Zealand's

New Zealand in the Vietnam War

New Zealand's involvement in the Vietnam War was highly controversial, sparking widespread protest at home from anti-Vietnam War movements modelled on their American counterparts...

; while Australia introduced conscription

Conscription in Australia

Conscription in Australia, or mandatory military service also known as National Service, has a controversial history dating back to the first years of nationhood...

, New Zealand sent only a token force. Australia has continued to be more committed to the American alliance, ANZUS

ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty is the military alliance which binds Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States to cooperate on defence matters in the Pacific Ocean area, though today the treaty is understood to relate to attacks...

, than New Zealand; although both countries felt considerable unease about American military policy in the 1980s, New Zealand angered the United States by refusing port access to nuclear ships into its nuclear-free zone

New Zealand's nuclear-free zone

In 1984, Prime Minister David Lange barred nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed ships from using New Zealand ports or entering New Zealand waters. Under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, territorial sea, land and airspace of New Zealand became nuclear-free zones...

from 1985 and in retaliation, the United States 'suspended' its obligations otherwise owed under the alliance treaty to New Zealand. Australia has made a significant contribution to the Iraq War

Australian contribution to the 2003 invasion of Iraq

The Howard Government supported the disarmament of Iraq during the Iraq disarmament crisis. Australia later provided one of the four most substantial combat force contingents during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, under the operational codename Operation Falconer. Part of its contingent were among the...

, while New Zealand's much smaller military contribution was limited to UN-authorised reconstruction tasks.

ANZAC Bridge

The ANZAC Bridge or Anzac Bridge , replacing the earlier Glebe Island Bridge, is a large cable-stayed bridge spanning Johnstons Bay between Pyrmont and Glebe Island in proximity to the central business district of Sydney, Australia...

in Sydney was given its current name on Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth countries since the end of World War I to remember the members of their armed forces who have died in the line of duty. This day, or alternative dates, are also recognized as special days for war remembrances in many non-Commonwealth...

in 1998 to honour the memory of the ANZAC serving in World War I. An Australian Flag

Flag of Australia

The flag of Australia is a defaced Blue Ensign: a blue field with the Union Flag in the canton , and a large white seven-pointed star known as the Commonwealth Star in the lower hoist quarter...

flies atop the eastern pylon and a New Zealand Flag

Flag of New Zealand

The flag of New Zealand is a defaced Blue Ensign with the Union Flag in the canton, and four red stars with white borders to the right. The stars represent the constellation of Crux, the Southern Cross....

flies atop the western pylon. A bronze memorial statue of a digger

Digger (soldier)

Digger is an Australian and New Zealand military slang term for soldiers from Australia and New Zealand. It originated during World War I.- Origin :...

holding a Lee Enfield rifle pointing down was placed on the western end of the bridge on ANZAC Day in 2000. A statue of a New Zealand soldier was added to a plinth across the road from the Australian Digger, facing towards the east, and unveiled by Prime Minister of New Zealand

Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of New Zealand is New Zealand's head of government consequent on being the leader of the party or coalition with majority support in the Parliament of New Zealand...

Helen Clark

Helen Clark

Helen Elizabeth Clark, ONZ is a New Zealand political figure who was the 37th Prime Minister of New Zealand for three consecutive terms from 1999 to 2008...

in the presence of Premier of New South Wales Morris Iemma

Morris Iemma

Morris Iemma , is a former Australian politician and 40th Premier of New South Wales, succeeding Bob Carr after he resigned on 3 August 2005. Iemma led the Australian Labor Party to victory in the 2007 election before resigning as Premier on 5 September 2008, and as a Member of Parliament on 19...

on Sunday 27 April 2008.

In 2001 the Australia-New Zealand Memorial

Australia-New Zealand Memorial, Canberra

The Australia–New Zealand Memorial in Canberra, Australia, commemorates the relationship between New Zealand and Australia, and stands at the corner of ANZAC Parade and Constitution Avenue, the former bisecting the Parliamentary Triangle and the latter forming the base of the triangle that...

was opened by the prime ministers of both countries on ANZAC Parade, Canberra

ANZAC Parade, Canberra

This article is about the road in Canberra. For other uses, see Anzac Parade .ANZAC Parade, a significant road and thoroughfare in the Australian capital Canberra, is used for ceremonial occasions and is the site of many major military memorials.Named in honour of the Australian and New Zealand...

. The memorial commemorates the shared effort to achieve common goals in both peace and war.

Exploration

Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was an Australasian scientific team that explored part of Antarctica between 1911 and 1914. It was led by the Australian geologist Douglas Mawson, who was knighted for his achievements in leading the expedition. In 1910 he began to plan an expedition to chart...

1911-1914 established radio connection back to Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

via Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island lies in the southwest corner of the Pacific Ocean, about half-way between New Zealand and Antarctica, at 54°30S, 158°57E. Politically, it has formed part of the Australian state of Tasmania since 1900 and became a Tasmanian State Reserve in 1978. In 1997 it became a world heritage...

, surveyed King George V Land and examined the rock formation

Rock formation

This is a list of rock formations that include isolated, scenic, or spectacular surface rock outcrops. These formations are usually the result of weathering and erosion sculpting the existing rock...

s of Wilkes Land

Wilkes Land

Wilkes Land is a large district of land in eastern Antarctica, formally claimed by Australia as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory, though the validity of this claim has been placed for the period of the operation of the Antarctic Treaty, to which Australia is a signatory...

. Mawson's Huts

Mawson's Huts

"Mawson's Huts" are the collection of buildings located at Cape Denison, Commonwealth Bay, in the far eastern sector of the Australian Antarctic Territory, some 3000 km south of Hobart...

at Cape Denison

Cape Denison

Cape Denison is a rocky point at the head of Commonwealth Bay in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1912 by the Australasian Antarctic Expedition under Douglas Mawson, who named it for Sir Hugh Denison of Sydney, a patron of the expedition...

survive to the current day as habitations at the expedition's chosen base. The expedition's Western Base Party

Western Base Party

The Western Base Party was a successful exploration party of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition. The eight-man Western Party was deposited by the Aurora on the Shackleton Ice Shelf at Queen Mary Land. The leader of the team was Frank Wild and the party included the geologist Charles Hoadley.The...

made a number of discoveries and explored into Kaiser Wilhelm II Land

Kaiser Wilhelm II Land

Kaiser Wilhelm II Land is the part of Antarctica lying between Cape Penck, at 87°43'E, and Cape Filchner, at 91°54'E and is claimed as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory, although this claim is not universally recognized....

from initial stationing in Queen Mary Land. The territorially acquisitive BANZARE expedition of 1929-1931, additionally collaborating with the UK, mapped the coastline of Antarctica and discovered Mac Robertson Land and Princess Elizabeth Land

Princess Elizabeth Land

Princess Elizabeth Land is the sector of the Australian Antarctic Territory between longitude 73° east and Cape Penck 87°43' east. Princess Elizabeth Land is located between 64°56'S and 90°00'S and between 73°35' E and 87°43'E...

. Both expeditions reported voluminously.

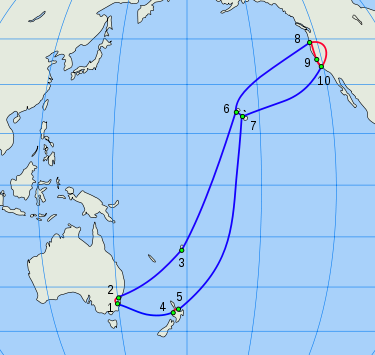

Aerial crossing of the Tasman was first achieved by Charles Kingsford-Smith with Charles Ulm

Charles Ulm

Charles Thomas Philippe Ulm AFC was a pioneer Australian aviator.-World War I:Ulm joined the AIF in September 1914, lying about his name and age to get in. He fought and was wounded at Gallipoli in 1915, and on the Western Front in 1918.Charles Ulm was married twice. In 1919 he married Isabel...

and crew travelling by return journey in 1928, improving upon failure by Moncrieff and Hood

Moncrieff and Hood

Lieutenant John Moncrieff and Captain George Hood were two New Zealanders who vanished on 10 January 1928 while attempting the first trans-Tasman flight from Australia to New Zealand...

deceased earlier the same year. Guy Menzies

Guy Menzies

Guy Lambton Menzies was the Australian aviator who flew the first solo trans-Tasman flight, from Sydney, Australia to the West Coast of New Zealand, on 7 January 1931....

then completed solo crossing in 1931. Rowing crossing was first successfully completed, solo, by Colin Quincey in 1977 and then by teams of kayakers in 2007

Crossing the Ditch

Crossing the Ditch was the effort of adventurers Justin Jones and James Castrission to become the first to cross the Tasman Sea and travel from Australia to New Zealand by sea kayak....

. A pioneering solo kayak

Kayak

A kayak is a small, relatively narrow, human-powered boat primarily designed to be manually propelled by means of a double blade paddle.The traditional kayak has a covered deck and one or more cockpits, each seating one paddler...

journey from Tasmania by Andrew McAuley

Andrew McAuley

Andrew McAuley was an Australian adventurer. He is best known for his mountaineering and sea kayaking in remote parts of the world. He is presumed to have died following his disappearance at sea while attempting to kayak 1600 km across the Tasman Sea in February 2007.-Personal:McAuley was...

in early 2007 ended with his disappearance at sea and presumed death in New Zealand waters 30 nm

Nautical mile

The nautical mile is a unit of length that is about one minute of arc of latitude along any meridian, but is approximately one minute of arc of longitude only at the equator...

short of landfall at Milford Sound

Milford Sound

Milford Sound is a fjord in the south west of New Zealand's South Island, within Fiordland National Park, Piopiotahi Marine Reserve, and the Te Wahipounamu World Heritage site...

.

Telecommunications

La Perouse, New South Wales

Lapérouse is a suburb in south-eastern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The suburb of Lapérouse is located about 14 kilometres south-east of the Sydney central business district, in the City of Randwick....

to Wakapuaka, New Zealand. The major part of that cable was renewed in 1895 and it was withdrawn from service in 1932. A second trans-Tasman submarine cable

Submarine communications cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the sea bed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean....

was laid in 1890 between Sydney and Wellington, New Zealand and then in 1901 the Pacific cable from Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island is a small island in the Pacific Ocean located between Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. The island is part of the Commonwealth of Australia, but it enjoys a large degree of self-governance...

was landed in Doubtless Bay, North Island

North Island

The North Island is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the much less populous South Island by Cook Strait. The island is in area, making it the world's 14th-largest island...

. In 1912 a 1225 nm long cable was laid from Sydney to Auckland

Auckland

The Auckland metropolitan area , in the North Island of New Zealand, is the largest and most populous urban area in the country with residents, percent of the country's population. Auckland also has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world...

.

The two countries additionally established communication via undersea laid coaxial cable

Coaxial cable

Coaxial cable, or coax, has an inner conductor surrounded by a flexible, tubular insulating layer, surrounded by a tubular conducting shield. The term coaxial comes from the inner conductor and the outer shield sharing the same geometric axis...

in July 1962, and the NZPO-OTC

Overseas Telecommunications Commission

The Overseas Telecommunications Commission was established by an Act of Parliament in August 1946. It inherited facilities and resources from Amalgamated Wireless Australasia Limited and Cable & Wireless, and was charged with responsibility for all international telecommunications services into,...

joint venture

Joint venture

A joint venture is a business agreement in which parties agree to develop, for a finite time, a new entity and new assets by contributing equity. They exercise control over the enterprise and consequently share revenues, expenses and assets...

TASMAN cable laid in 1975. These were retired by effect of the laying of analog signal

Analog signal

An analog or analogue signal is any continuous signal for which the time varying feature of the signal is a representation of some other time varying quantity, i.e., analogous to another time varying signal. It differs from a digital signal in terms of small fluctuations in the signal which are...

submarine cable linking Australia's Bondi Beach to Takapuna, New Zealand

Takapuna

Takapuna is a central, coastal suburb of North Shore City, located in the northern North Island of New Zealand, at the beginning of a south-east-facing peninsula forming the northern side of the Waitemata Harbour...

via Norfolk Island in 1983, which itself in turn was supplemented and eventually outmoded by optical fiber cable

Optical fiber cable

An optical fiber cable is a cable containing one or more optical fibers. The optical fiber elements are typically individually coated with plastic layers and contained in a protective tube suitable for the environment where the cable will be deployed....

laid between Paddington, New South Wales

Paddington, New South Wales

Paddington is an inner-city, eastern suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Paddington is located 3 kilometres east of the Sydney central business district and lies across the local government areas of the City of Sydney and the Municipality of Woollahra...

and Whenuapai, Auckland

Whenuapai

Whenuapai is a suburb and airport located in the western Waitakere area of Auckland City, in the North Island of New Zealand. It is located on the northwestern shore of the Waitemata Harbour, 15 kilometres to the northwest of Auckland's city centre. It is one of the landing points for the Southern...

in 1995.

The trans-Tasman leg of the high capacity fibre-optic Southern Cross Cable

Southern Cross Cable

The Southern Cross Cable, operated by Bermuda company Southern Cross Cables Limited, is a trans-Pacific network of telecommunications cables commissioned in 2000....

has been operational from Alexandria, New South Wales

Alexandria, New South Wales

Alexandria is an inner-city suburb of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Alexandria is located 4 kilometres south of the Sydney central business district and is part of the local government area of the City of Sydney...

to Whenuapai since 2001. Another high capacity direct linkage is proposed for construction to be operational in 2013, and yet another for early 2014.

Migration

There are many people who have emigrated from New Zealand to AustraliaNew Zealanders in Australia

New Zealanders in Australia consist of Australian people who have origins in New Zealand, as well as New Zealand migrants and expatriates based in Australia. Migration from New Zealand to Australia is a very common phenomenon, given Australia's close proximity as a neighboring country...

, including Premier of South Australia, Mike Rann

Mike Rann

Michael David Rann MHA, CNZM , Australian politician, served as the 44th Premier of South Australia. He led the South Australian branch of the Australian Labor Party to minority government at the 2002 election, before attaining a landslide win at the 2006 election...

, comedian turned psychologist Pamela Stephenson

Pamela Stephenson

Pamela Helen Stephenson Connolly is a New Zealand-born Australian clinical psychologist and writer now resident in the United Kingdom. She is best known for her work as an actress and comedian during the 1980s...

and actor Russell Crowe

Russell Crowe

Russell Ira Crowe is a New Zealander Australian actor , film producer and musician. He came to international attention for his role as Roman General Maximus Decimus Meridius in the 2000 historical epic film Gladiator, directed by Ridley Scott, for which he won an Academy Award for Best Actor, a...

. Australians who have emigrated to New Zealand

Australian New Zealander

There are 68,000 Australians in New Zealand. They include expatriates, students, workers, families and New Zealand citizens who have Australian origins....

include the 17th and 23rd Prime Ministers of New Zealand

Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of New Zealand is New Zealand's head of government consequent on being the leader of the party or coalition with majority support in the Parliament of New Zealand...

Sir Joseph Ward

Joseph Ward

Sir Joseph George Ward, 1st Baronet, GCMG was the 17th Prime Minister of New Zealand on two occasions in the early 20th century.-Early life:...

and Michael Savage

Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage was the first Labour Prime Minister of New Zealand.- Early life :Born in Tatong, Victoria, Australia, Savage first became involved in politics while working in that state. He emigrated to New Zealand in 1907. There he worked in a variety of jobs, as a miner, flax-cutter and...

, Russel Norman

Russel Norman

Dr Russel William Norman is a New Zealand politician and environmentalist. He is a Member of Parliament and co-leader of the Green Party alongside Metiria Turei.- Early life :...

, co-leader of the Green Party

Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand

The Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand is a political party that has seats in the New Zealand parliament. It focuses firstly on environmentalism, arguing that all other aspects of humanity will cease to be of concern if there is no environment to sustain it...

, and Matt Robson

Matt Robson

Matthew Peter Robson is a New Zealand politician. He is deputy leader of the Progressive Party, and served in the Parliament from 1996 to 2005, first as a member of the Alliance, then as a Progressive.-Early years:...

, deputy leader of the Progressive Party

New Zealand Progressive Party

Jim Anderton's Progressive Party , is a New Zealand political party generally somewhat to the left of its ally, the Labour Party....

.

Permanent residency

Permanent residency refers to a person's visa status: the person is allowed to reside indefinitely within a country of which he or she is not a citizen. A person with such status is known as a permanent resident....

between Australia and New Zealand.

Since 1973 the informal Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement

Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement

The Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement is an informal agreement between Australia and New Zealand to allow for the free movement of citizens of one nation to the other.- Treaty history :...

has allowed for the free movement of citizens of one nation to the other. The only major exception to these travel privileges is for individuals with outstanding warrants or criminal backgrounds who are deemed dangerous or undesirable for the migrant nation and its citizens. In recent decades, many New Zealanders have migrated to Australian cities such as Sydney, Brisbane

Brisbane

Brisbane is the capital and most populous city in the Australian state of Queensland and the third most populous city in Australia. Brisbane's metropolitan area has a population of over 2 million, and the South East Queensland urban conurbation, centred around Brisbane, encompasses a population of...

, Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

and Perth

Perth, Western Australia

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia and the fourth most populous city in Australia. The Perth metropolitan area has an estimated population of almost 1,700,000....

. Many such New Zealanders are Maori Australian

Maori Australian

A Māori Australian is an Australian of Māori heritage. In 2008, there were approximately 100,000 people with Māori ancestry living in Australia. Māori Australians constitute Australia's largest Polynesian ethnic group...

s. New Zealand passport holders are issued with special category visa

Special Category Visa

A Special Category Visa is a type of Australian visa granted to most New Zealand citizens on arrival in Australia. New Zealand Citizens may then reside in Australia indefinitely under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement.- History :...

s on arrival in Australia. Although this agreement is reciprocal there has been resulting significant net migration from New Zealand to Australia. In 2001 there were eight times more New Zealanders living in Australia than Australians living in New Zealand and in 2006 it was estimated that Australia's real income per person was 32 per cent higher than New Zealand's. and territories. Comparative surveys of median household incomes

Median household income in Australia and New Zealand

Median household income is commonly used to measure the relative prosperity of populations in different geographical locations. It divides households into two equal segments with the first half of households earning less than the median household income and the other half earning more.Since 2000...

also confirm that those incomes are lower in New Zealand than in most of the Australian States and Territories. Visits in each direction exceeded one million in 2009, and there are around half a million New Zealand citizens in Australia and about 65,000 Australians in New Zealand. There have been complaints in New Zealand that there is a clearly manifested brain drain

Brain drain

Human capital flight, more commonly referred to as "brain drain", is the large-scale emigration of a large group of individuals with technical skills or knowledge. The reasons usually include two aspects which respectively come from countries and individuals...

to Australia.

New Zealanders in Australia previously had immediate access to Australian welfare benefits

Social Security (Australia)

Social Security, in Australia, refers to a system of social welfare payments provided by Commonwealth Government of Australia. These payments are administered by a Government body named Centrelink...

and were sometimes characterised as bludger

Bludger

Bludger may refer to:*A metal band from Leeds, UK*A type of ball used in the fictional game Quidditch in the fictional Harry Potter universe*A pimp, in 19th century slang*In Australian slang, a lazy person...

s. This was in 2001 described by New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark as a "modern myth". Regulations changed in 2001 whereby New Zealanders must wait two years before being eligible for such payments.

New Zealand Ministry of Education figures show the number of Australians at New Zealand tertiary institutions almost doubled from 1,978 students in 1999 to 3,916 in 2003. In 2004 more than 2700 Australians received student loans and 1220 a student allowance. Unlike other overseas students, Australians pay the same fees for higher education as New Zealanders and are eligible for student loans and allowances. New Zealand students are not treated on the same basis as Australian students in Australia

Tertiary education in Australia

Tertiary education in Australia is primarily study at University or a Technical college in order to receive a qualification or further skills and training....

.

Persons born in New Zealand continue to be the second largest source of immigration to Australia

Immigration to Australia

Immigration to Australia is estimated to have begun around 51,000 years ago when the ancestors of Australian Aborigines arrived on the continent via the islands of the Malay Archipelago and New Guinea. Europeans first landed in the 17th and 18th Centuries, but colonisation only started in 1788. The...

, representing 11% of total permanent additions in 2005–06 and accounting for 2.3% of Australia's population at June 2006. At 30 June 2009, an estimated 548,256 New Zealand citizens were present in Australia.

Trade

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community The European Economic Community (EEC) The European Economic Community (EEC) (also known as the Common Market in the English-speaking world, renamed the European Community (EC) in 1993The information in this article primarily covers the EEC's time as an independent...

in 1973. Effective from 1 January 1983 the two countries concluded the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations

Closer Economic Relations

Closer Economic Relations is a free trade agreement between the governments of New Zealand and Australia. It is also known as the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement and sometimes shortened to...

Trade Agreement (ANZCERTA) for the purpose of allowing each country access to the other's markets. Two-way trade between Australia and New Zealand was A$20.6 billion (NZ$25 billion) in 2009, including goods and services, only slightly lower than the previous year despite the economic downturn. The total accumulated bilateral investment stands at over A$90 billion (NZ$ 110 billion).

Flowing from the implementation of the ANZCERTA:

- by agreement from 1988 there will be consultation between the respective governments as part of any variation to industry assistance measuresCorporate welfareCorporate welfare is a pejorative term describing a government's bestowal of money grants, tax breaks, or other special favorable treatment on corporations or selected corporations. The term compares corporate subsidies and welfare payments to the poor, and implies that corporations are much less...

and work towards harmonisation of common administrative proceduresAustralian Quarantine and Inspection ServiceThe Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service is the Australian government agency responsible for enforcing Australian quarantine laws...

for quarantineQuarantineQuarantine is compulsory isolation, typically to contain the spread of something considered dangerous, often but not always disease. The word comes from the Italian quarantena, meaning forty-day period.... - additional services were brought within the Agreement's scope from January 1989

- remaining tariffTariffA tariff may be either tax on imports or exports , or a list or schedule of prices for such things as rail service, bus routes, and electrical usage ....

s and quantitative restrictionsImport quotaAn import quota is a type of protectionist trade restriction that sets a physical limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported into a country in a given period of time....

in bilateral tradeBilateral tradeBilateral trade or clearing trade is trade exclusively between two states, particularly, barter trade based on bilateral deals between governments, and without using hard currency for payment...

were eliminated prior to 1 July 1990 - from 1991 under the Joint Accreditation System of Australia and New ZealandJoint Accreditation System of Australia and New ZealandStandards and conformance underpin almost every aspect of our daily lives, from the accuracy of our watches to ensuring the quality of our drinking water and upholding safety in our workplaces...

, JAS-ANZ has existed as the joint authority for the accreditation of conformity assessmentConformity assessmentConformity assessment, also known as compliance assessment , , , is any activity to determine, directly or indirectly, that a process, product, or service meets relevant technical standards and fulfills relevant requirements....

bodies in the fields of certification and inspection; also, a Government ProcurementProcurementProcurement is the acquisition of goods or services. It is favourable that the goods/services are appropriate and that they are procured at the best possible cost to meet the needs of the purchaser in terms of quality and quantity, time, and location...

Agreement was reached and legislation to establish Food Standards Australia New ZealandFood Standards Australia New ZealandFood Standards Australia New Zealand is the governmental body responsible for developing food standards for Australia and New Zealand .FSANZ develops food standards after consulting with other government agencies and stakeholders...

was promulgated that year. - a double taxationDouble taxationDouble taxation is the systematic imposition of two or more taxes on the same income , asset , or financial transaction . It refers to taxation by two or more countries of the same income, asset or transaction, for example income paid by an entity of one country to a resident of a different country...

agreementTax treatyMany countries have agreed with other countries in treaties to mitigate the effects of double taxation . Tax treaties may cover income taxes, inheritance taxes, value added taxes, or other taxes...

was sealed in 1995 - cooperation to harmonise customsCustomsCustoms is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting and safeguarding customs duties and for controlling the flow of goods including animals, transports, personal effects and hazardous items in and out of a country...

policies and procedures has existed since 1996 - agreement on food inspectionFood safetyFood safety is a scientific discipline describing handling, preparation, and storage of food in ways that prevent foodborne illness. This includes a number of routines that should be followed to avoid potentially severe health hazards....

measures was reached in 1996 - from 1998 goods that may legally be sold in either country may be sold in the otherSingle marketA single market is a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with common policies on product regulation, and freedom of movement of the factors of production and of enterprise and services. The goal is that the movement of capital, labour, goods, and services between the members...

and a person who is registered to practise an occupation in either country is entitled to practise an equivalent occupation in the otherMutual recognition agreementA mutual recognition agreement or MRA is an international agreement by which two or more countries agree to recognize one another's conformity assessments....

. A Reciprocal Health Care Agreement was reached in the same year. - the Consultative Group on BiosecurityBiosecurityBiosecurity is a set of preventive measures designed to reduce the risk of transmission of infectious diseases, quarantined pests, invasive alien species, living modified organisms...