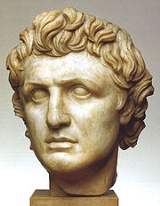

Attalus I

Encyclopedia

Attalus I surnamed Soter ruled Pergamon

, an Ionian Greek polis

(what is now Bergama

, Turkey

), first as dynast, later as king, from 241 BC to 197 BC. He was the second cousin and the adoptive son of Eumenes I

, whom he succeeded, and was the first of the Attalid dynasty

to assume the title of king in 238 BC. He was the son of Attalus and his wife Antiochis.

Attalus won an important victory over the Galatia

ns, newly arrived Celt

ic tribes from Thrace

, who had been, for more than a generation, plundering and exacting tribute throughout most of Asia Minor

without any serious check. This victory, celebrated by the triumphal monument at Pergamon (famous for its Dying Gaul) and the liberation from the Gallic "terror" which it represented, earned for Attalus the name of "Soter", and the title of "king

". A courageous and capable general and loyal ally of Rome

, he played a significant role in the first and second Macedonian Wars

, waged against Philip V of Macedon

. He conducted numerous naval operations, harassing Macedonian interests throughout the Aegean

, winning honors, collecting spoils, and gaining for Pergamon possession of the Greek islands of Aegina

during the first war, and Andros

during the second, twice narrowly escaping capture at the hands of Philip.

Attalus was a protector of the Greek cities of Anatolia

and viewed himself as the champion of Greeks against barbarians. During his reign he established Pergamon as a considerable power in the Greek East

. He died in 197 BC, shortly before the end of the second war, at the age of 72, having suffered an apparent stroke

while addressing a Boeotia

n war council some months before. He enjoyed a famously happy domestic life, shared with his wife and four sons. He was succeeded as king by his son Eumenes II

.

, the founder of the Attalid dynasty

, and Eumenes, the father of Eumenes I

, Philetaerus' successor; he is mentioned, along with his uncles, as a benefactor of Delphi

, won fame as a charioteer, winning at Olympia

, and was honored with a monument at Pergamon.

Attalus was a young child when his father died, sometime before 241 BC, after which he was adopted by Eumenes I, the incumbent dynast. Attalus' mother, Antiochis

, was related to the Seleucid

royal family (being a granddaughter of Seleucus I Nicator

) with her marriage to Attalus' father likely arranged by Philetaerus to solidify his power. This would be consistent with the conjecture that Attalus' father had been Philetaerus' heir designate, but was succeeded by Eumenes, since Attalus I was too young when his father died.

According to the 2nd century AD Greek writer Pausanias

According to the 2nd century AD Greek writer Pausanias

, "the greatest of his achievements" was the defeat of the "Gauls

" . Pausanias was referring to the Galatians, immigrant Celts from Thrace

, who had recently settled in Galatia

in central Asia Minor

, and whom the Romans and Greeks called Gauls, associating them with the Celts of what is now France, Switzerland, and northern Italy. Since the time of Philetaerus, the first Attalid ruler, the Galatians had posed a problem for Pergamon, indeed for all of Asia Minor, by exacting tributes to avoid war or other repercussions. Eumenes I had (probably), along with other rulers, dealt with the Galatians by paying these tributes. Attalus however refused to pay them, being the first such ruler to do so. As a consequence, the Galatians set out to attack Pergamon. Attalus met them near the sources of the river Caïcus and won a decisive victory, after which, following the example of Antiochus I, Attalus took the name of Soter, which means "savior", and claimed the title of king. The victory brought Attalus legendary fame. A story arose, related by Pausanias, of an oracle who had foretold these events a generation earlier:

Pausanius adds that by "son of a bull" the oracle "meant Attalus, king of Pergamon, who was styled bull-horned". On the acropolis of Pergamon was erected a triumphal monument, which included the famous sculpture the Dying Gaul

, commemorating this battle.

, the younger brother of Seleucus II Callinicus

, and ruler of Seleucid Asia Minor from his capital at Sardis

. Attalus defeated the Gauls and Antiochus at the battle of Aphrodisium and again at a second battle in the east. Subsequent battles were fought and won against Antiochus alone: in Hellespontine Phrygia

, where Antiochus was perhaps seeking refuge with his father-in law, Ziaelas the king of Bithynia

; near Sardis in the spring of 228 BC; and, in the final battle of the campaign, further south in Caria

on the banks of the Harpasus, a tributary of the Maeander.

As a result of these victories, Attalus gained control over all of Seleucid Asia Minor north of the Taurus Mountains

. He was able to hold onto these gains in the face of repeated attempts by Seleucus III Ceraunus

, eldest son and successor of Seleucus II, to recover the lost territory, culminating in Seleucus III himself crossing the Taurus, only to be assassinated by members of his army in 223 BC. Achaeus

, who had accompanied Seleucus III, assumed control of the army. He was offered and refused the kingship in favor of Seleucus III's younger brother Antiochus III the Great

, who then made Achaeus governor of Seleucid Asia Minor north of the Taurus. Within two years Achaeus had recovered all the lost Seleucid territories, "shut up Attalus within the walls of Pergamon", and assumed the title of king.

After a period of peace, in 218 BC, while Achaeus was involved in an expedition to Selge south of the Taurus, Attalus, with some Thracian Gauls, recaptured his former territories. However Achaeus returned from victory in Selge in 217 BC and resumed hostilities with Attalus.

Under a treaty of alliance with Attalus, Antiochus crossed the Taurus in 216 BC, attacked Achaeus and besieged Sardis, and in 214 BC, the second year of the siege, was able to take the city. However the citadel remained under Achaeus' control. Under the pretense of a rescue, Achaeus was finally captured and put to death, and the citadel surrendered. By 213 BC, Antiochus had regained control of all of his Asiatic provinces.

, Attalus had sometime before 219 BC become allied with Philip's enemies the Aetolian League

, a union of Greek states in Aetolia

in central Greece, having funded the fortification of Elaeus, an Aetolian stronghold in Calydon

ia, near the mouth of the river Acheloos

.

Philip's alliance with Hannibal of Carthage

in 215 BC also caused concern in Rome

, then involved in the Second Punic War

. In 211 BC, a treaty was signed between Rome and the Aetolian League, a provision of which allowed for the inclusion of certain allies of the League, Attalus being one of these. Attalus was elected one of the two strategoi

(generals) of the Aetolian League, and in 210 BC his troops probably participated in capturing the island of Aegina

, acquired by Attalus as his base of operations in Greece.

In the following spring (209 BC), Philip marched south into Greece. Under command of Pyrrhias, Attalus' colleague as strategos, the allies lost two battles at Lamia

. Attalus himself went to Greece in July and was joined on Aegina by the Roman proconsul

P. Sulpicius Galba

who wintered there. The following summer (208 BC) the combined fleet of thirty-five Pergamene and twenty-five Roman ships failed to take Lemnos

, but occupied and plundered the countryside of the island of Peparethos (Skopelos

), both Macedonian possessions. Attalus and Sulpicius then attended a meeting in Heraclea Trachinia of the Council of the Aetolians, at which the Roman argued against making peace with Philip.

When hostilities resumed, they sacked both Oreus

, on the northern coast of Euboea

and Opus

, the chief city of eastern Locris

. The spoils from Oreus had been reserved for Sulpicius, who returned there, while Attalus stayed to collect the spoils from Opus. With their forces divided, Philip attacked Opus. Attalus, caught by surprise, was barely able to escape to his ships.

Attalus was now forced to return to Asia, for he had learned at Opus that, at the instigation of Philip, Prusias I

king of Bithynia, related to Philip by marriage, was moving against Pergamon. Soon after, the Romans also abandoned Greece to concentrate their forces against Hannibal, their objective of preventing Philip from aiding Hannibal having been achieved. In 206 BC the Aetolians sued for peace on conditions imposed by Philip. A treaty was drawn up at Phoenice in 205 BC, formally ending the First Macedonian War

. Attalus was included as an adscriptus on the side of Rome. He retained Aegina, but had accomplished little else. Since Prusias was also included in the treaty, the war between Attalus and Prusias must also have ended by that time.

, which discovered verses saying that if a foreigner were to make war on Italy, he could be defeated if the Magna Idaea, the Mother Goddess, associated with Mount Ida

in Phrygia

, were brought to Rome. Hoping to bring about a speedy conclusion to the war with Hannibal, a distinguished delegation, led by M. Valerius Laevinus, was dispatched to Pergamon, to seek Attalus' aid. According to Livy

, Attalus received the delegation warmly, and "handed over to them the sacred stone which the natives declared to be 'the Mother of the Gods', and bade them carry it to Rome." In Rome the goddess became known as the Magna Mater.

and in Asia Minor. In the spring of 201 BC he took Samos

and the Egyptian

fleet stationed there. He then besieged Chios

to the north. These events caused Attalus, allied with Rhodes

, Byzantium

and Cyzicus

, to enter the war. A large naval battle occurred in the strait between Chios and the mainland, just southwest of Erythrae

. According to Polybius

, fifty-three decked warships and over one hundred and fifty smaller warships, took part on the Macedonian side, with sixty-five decked warships and a number of smaller warships on the allied side. During the battle Attalus, having become isolated from his fleet and pursued by Philip, was forced to run his three ships ashore, narrowly escaping by spreading various royal treasures on the decks of the grounded ships, causing his pursuers to abandon the pursuit in favor of plunder.

The same year, Philip invaded Pergamon; although unable to take the easily defended city, in part due to precautions taken by Attalus to provide for additional fortifications, he demolished the surrounding temples and altars.

Meanwhile, Attalus and Rhodes sent envoys to Rome, to register their complaints against Philip.

. Acarnania

ns with Macedonian support invaded Attica

, causing Athens

, which had previously maintained its neutrality, to seek help from the enemies of Philip. Attalus, with his fleet at Aegina, received an embassy from Athens, to come to the city for consultations. A few days later, he learned that Roman ambassadors were also at Athens, and decided to go there at once. His reception at Athens was extraordinary. Polybius writes:

Sulpicius Galba, now consul

, convinced Rome to declare war on Philip and asked Attalus to meet up with the Roman fleet and again conduct a naval campaign, harassing Macedonian possessions in the Aegean. In the spring of 199 BC, the combined Pergamon and Roman fleets took Andros

in the Cyclades

, the spoils going to the Romans and the island to Attalus. From Andros they sailed south, made a fruitless attack on another Cycladic island, Kithnos, turned back north, scavenged the fields of Skiathos

off the coast of Magnesia

, for food, and continued north to Mende

, where the fleets were wracked by storm. On land they were repulsed at Cassandrea, suffering heavy loss. They continued northeast along the Macedonian coast to Acanthus

, which they sacked, after which they returned to Euboea, their vessels laden with spoils. On their return, the two leaders went to Heraclea to meet with the Aetolians, who under the terms of their treaty, had asked Attalus for a thousand soldiers. He refused, citing the Aetolians' own refusal to honor Attalus' request to attack Macedonia during Philip's attack on Pergamon two years earlier. Resuming operations, Attalus and the Romans attacked but failed to take Oreus and, deciding to leave a small force to invest it, attacked across the straight in Thessaly

. When they returned to Oreus, they again attacked, this time successfully, the Romans taking the captives, Attalus the city. The campaigning season now over, Attalus attended the Eleusinian Mysteries

and then returned to Pergamon having been away for over two years.

In the spring of 198 BC, Attalus returned to Greece with twenty-three quinquereme

s joining a fleet of twenty Rhodian decked warships at Andros, to complete the conquest of Euboea begun the previous year. Soon joined by the Romans, the combined fleets took Eretria

and later Carystus

. Thus, the allies controlled all of Euboea except for Chalcis

. The allied fleet then sailed for Cenchreae in preparation for an attack on Corinth

. Meanwhile, the new Roman consul for that year, Titus Quinctius Flamininus

, had learned that the Achaean League

, allies of Macedon, had had a change in leadership which favored Rome. With the hope of inducing the Achaeans to abandon Philip and join the allies, envoys were sent, including Attalus himself, to Sicyon

, where they offered the incorporation of Corinth into the Achaean League. Attalus apparently so impressed the Sicyonians, that they erected a colossal statue of him in their market place and instituted sacrifices in his honor. A meeting of the League was convened and after a heated debate and the withdrawal of some of delegates the rest agreed to join the alliance. Attalus led his army from Cenchreae (now controlled by the allies) through the Isthmus and attached Corinth from the north, controlling the access to Lechaeum, the Corinthian port on the Gulf of Corinth, the Romans attacked from the east controlling the approaches to Cenchreae, with the Achaeans attacking from the west controlling the access to the city via the Sicyonian gate. However the city held, and when Macedonian reinforcements arrived, the siege was abandoned. The Achaeans were dismissed, the Romans left for Corcyra, while Attalus sailed for Piraeus

.

Early in 197 BC, Flamininus, summoned Attalus to join him at Elateia

(now in Roman hands) and from there they traveled together to attend a Boeotia

n council in Thebes to discuss which side Boeotia would take in the war. At the council Attalus spoke first, reminding the Boeotians of the many things he and his ancestors had done for them, but during his address he stopped talking and collapsed, with one side of his body paralyzed. Attalus was taken back to Pergamon, where he died around the time of the Battle of Cynoscephalae

, which brought about the end of the Second Macedonian War.

. They had four sons, Eumenes

, Attalus, Philetaerus and Athenaeus (after Apollonis' father). Polybius

describes Apollonis as "a woman who for many reasons deserves to be remembered, and with honor. Her claims upon a favourable recollection are that, though born of a private family, she became a queen, and retained that exalted rank to the end of her life, not by the use of meretricious fascinations, but by the virtue and integrity of her conduct in private and public life alike. Above all, she was the mother of four sons with whom she kept on terms of the most perfect affection and motherly love to the last day of her life."

The filial "affection" of the brothers as well as their upbringing is remarked on by several ancient sources. A decree of Antiochus IV praises "king Attalus and queen Apollonis … because of their virtue and goodness, which they preserved for their sons, managing their education in this way wisely and well." An inscription at Pergamon represents Apollonis as saying that "she always considered herself blessed and gave thanks to the gods, not for wealth or empire, but because she saw her three sons guarding the eldest and him reigning without fear among those who were armed." When Attalus died in 197 BC at the age of 72, he was succeeded by his eldest son Eumenes II. Polybius, describing Attalus' life says "and what is more remarkable than all, though he left four grown-up sons, he so well settled the question of succession, that the crown was handed down to his children's children without a single dispute."

Pergamon

Pergamon , or Pergamum, was an ancient Greek city in modern-day Turkey, in Mysia, today located from the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north side of the river Caicus , that became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon during the Hellenistic period, under the Attalid dynasty, 281–133 BC...

, an Ionian Greek polis

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

(what is now Bergama

Bergama

Bergama is a populous district, as well as the center city of the same district, in İzmir Province in western Turkey. By excluding İzmir's metropolitan area, it is one of the prominent districts of the province in terms of population and is largely urbanized at the rate of 53,6 per cent...

, Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

), first as dynast, later as king, from 241 BC to 197 BC. He was the second cousin and the adoptive son of Eumenes I

Eumenes I

Eumenes I was dynast of the city of Pergamon in Asia Minor from 263 BC until his death in 241 BC. He was the son of Eumenes, the brother of Philetaerus, the founder of the Attalid dynasty, and Satyra, daughter of Poseidonius...

, whom he succeeded, and was the first of the Attalid dynasty

Attalid dynasty

The Attalid dynasty was a Hellenistic dynasty that ruled the city of Pergamon after the death of Lysimachus, a general of Alexander the Great. The Attalid kingdom was the rump state left after the collapse of the Lysimachian Empire. One of Lysimachus' officers, Philetaerus, took control of the city...

to assume the title of king in 238 BC. He was the son of Attalus and his wife Antiochis.

Attalus won an important victory over the Galatia

Galatia

Ancient Galatia was an area in the highlands of central Anatolia in modern Turkey. Galatia was named for the immigrant Gauls from Thrace , who settled here and became its ruling caste in the 3rd century BC, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC. It has been called the "Gallia" of...

ns, newly arrived Celt

Celt

The Celts were a diverse group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Roman-era Europe who spoke Celtic languages.The earliest archaeological culture commonly accepted as Celtic, or rather Proto-Celtic, was the central European Hallstatt culture , named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria....

ic tribes from Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

, who had been, for more than a generation, plundering and exacting tribute throughout most of Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

without any serious check. This victory, celebrated by the triumphal monument at Pergamon (famous for its Dying Gaul) and the liberation from the Gallic "terror" which it represented, earned for Attalus the name of "Soter", and the title of "king

Basileus

Basileus is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs in history. It is perhaps best known in English as a title used by the Byzantine Emperors, but also has a longer history of use for persons of authority and sovereigns in ancient Greece, as well as for the kings of...

". A courageous and capable general and loyal ally of Rome

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

, he played a significant role in the first and second Macedonian Wars

Macedonian Wars

The Macedonian wars were a series of conflicts fought by Rome in the eastern Mediterranean, the Adriatic, and the Aegean. They resulted in Roman control or influence over the eastern Mediterranean basin, in addition to their hegemony in the western Mediterranean after the Punic wars.-First...

, waged against Philip V of Macedon

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V was King of Macedon from 221 BC to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of Rome. Philip was attractive and charismatic as a young man...

. He conducted numerous naval operations, harassing Macedonian interests throughout the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

, winning honors, collecting spoils, and gaining for Pergamon possession of the Greek islands of Aegina

Aegina

Aegina is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of Aeacus, who was born in and ruled the island. During ancient times, Aegina was a rival to Athens, the great sea power of the era.-Municipality:The municipality...

during the first war, and Andros

Andros

Andros, or Andro is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, approximately south east of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . Its surface is for the most part mountainous, with many fruitful and well-watered valleys. The area is...

during the second, twice narrowly escaping capture at the hands of Philip.

Attalus was a protector of the Greek cities of Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

and viewed himself as the champion of Greeks against barbarians. During his reign he established Pergamon as a considerable power in the Greek East

Greek East

"Greek East" and "Latin West" are terms used to distinguish between the two parts of the Greco-Roman world, specifically the eastern regions where Greek was the lingua franca, and the western parts where Latin filled this role...

. He died in 197 BC, shortly before the end of the second war, at the age of 72, having suffered an apparent stroke

Stroke

A stroke, previously known medically as a cerebrovascular accident , is the rapidly developing loss of brain function due to disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This can be due to ischemia caused by blockage , or a hemorrhage...

while addressing a Boeotia

Boeotia

Boeotia, also spelled Beotia and Bœotia , is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. It was also a region of ancient Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, the second largest city being Thebes.-Geography:...

n war council some months before. He enjoyed a famously happy domestic life, shared with his wife and four sons. He was succeeded as king by his son Eumenes II

Eumenes II

Eumenes II of Pergamon was king of Pergamon and a member of the Attalid dynasty. The son of king Attalus I and queen Apollonis, he followed in his father's footsteps and collaborated with the Romans to oppose first Macedonian, then Seleucid expansion towards the Aegean, leading to the defeat of...

.

Early life

Little is known about Attalus' early life. He was born a Greek, the son of Attalus, and Antiochis. The elder Attalus was the son of a brother (also called Attalus) of both PhiletaerusPhiletaerus

Philetaerus was the founder of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon in Anatolia.- Early life and career under Lysimachus :...

, the founder of the Attalid dynasty

Attalid dynasty

The Attalid dynasty was a Hellenistic dynasty that ruled the city of Pergamon after the death of Lysimachus, a general of Alexander the Great. The Attalid kingdom was the rump state left after the collapse of the Lysimachian Empire. One of Lysimachus' officers, Philetaerus, took control of the city...

, and Eumenes, the father of Eumenes I

Eumenes I

Eumenes I was dynast of the city of Pergamon in Asia Minor from 263 BC until his death in 241 BC. He was the son of Eumenes, the brother of Philetaerus, the founder of the Attalid dynasty, and Satyra, daughter of Poseidonius...

, Philetaerus' successor; he is mentioned, along with his uncles, as a benefactor of Delphi

Delphi

Delphi is both an archaeological site and a modern town in Greece on the south-western spur of Mount Parnassus in the valley of Phocis.In Greek mythology, Delphi was the site of the Delphic oracle, the most important oracle in the classical Greek world, and a major site for the worship of the god...

, won fame as a charioteer, winning at Olympia

Olympia, Greece

Olympia , a sanctuary of ancient Greece in Elis, is known for having been the site of the Olympic Games in classical times, comparable in importance to the Pythian Games held in Delphi. Both games were held every Olympiad , the Olympic Games dating back possibly further than 776 BC...

, and was honored with a monument at Pergamon.

Attalus was a young child when his father died, sometime before 241 BC, after which he was adopted by Eumenes I, the incumbent dynast. Attalus' mother, Antiochis

Antiochis

The name Antiochis, in Greek Ἀντιoχίς is the female name of Antiochus. Antiochis in Greek antiquity may refer to:-Hellenistic queens consort:*Antiochis, daughter of Achaeus, married to Attalus, and the mother of Attalus I, king of Pergamon...

, was related to the Seleucid

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire was a Greek-Macedonian state that was created out of the eastern conquests of Alexander the Great. At the height of its power, it included central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, today's Turkmenistan, Pamir and parts of Pakistan.The Seleucid Empire was a major centre...

royal family (being a granddaughter of Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi. In the Wars of the Diadochi that took place after Alexander's death, Seleucus established the Seleucid dynasty and the Seleucid Empire...

) with her marriage to Attalus' father likely arranged by Philetaerus to solidify his power. This would be consistent with the conjecture that Attalus' father had been Philetaerus' heir designate, but was succeeded by Eumenes, since Attalus I was too young when his father died.

Defeat of the Galatians

Pausanias (geographer)

Pausanias was a Greek traveler and geographer of the 2nd century AD, who lived in the times of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his Description of Greece , a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from firsthand observations, and is a crucial link between classical...

, "the greatest of his achievements" was the defeat of the "Gauls

Gauls

The Gauls were a Celtic people living in Gaul, the region roughly corresponding to what is now France, Belgium, Switzerland and Northern Italy, from the Iron Age through the Roman period. They mostly spoke the Continental Celtic language called Gaulish....

" . Pausanias was referring to the Galatians, immigrant Celts from Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

, who had recently settled in Galatia

Galatia

Ancient Galatia was an area in the highlands of central Anatolia in modern Turkey. Galatia was named for the immigrant Gauls from Thrace , who settled here and became its ruling caste in the 3rd century BC, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC. It has been called the "Gallia" of...

in central Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

, and whom the Romans and Greeks called Gauls, associating them with the Celts of what is now France, Switzerland, and northern Italy. Since the time of Philetaerus, the first Attalid ruler, the Galatians had posed a problem for Pergamon, indeed for all of Asia Minor, by exacting tributes to avoid war or other repercussions. Eumenes I had (probably), along with other rulers, dealt with the Galatians by paying these tributes. Attalus however refused to pay them, being the first such ruler to do so. As a consequence, the Galatians set out to attack Pergamon. Attalus met them near the sources of the river Caïcus and won a decisive victory, after which, following the example of Antiochus I, Attalus took the name of Soter, which means "savior", and claimed the title of king. The victory brought Attalus legendary fame. A story arose, related by Pausanias, of an oracle who had foretold these events a generation earlier:

- Then verily, having crossed the narrow strait of the Hellespont,

- The devastating host of the Gauls shall pipe; and lawlessly

- They shall ravage Asia; and much worse shall God do

- To those who dwell by the shores of the sea

- For a short while. For right soon the son of CronosCronusIn Greek mythology, Cronus or Kronos was the leader and the youngest of the first generation of Titans, divine descendants of Gaia, the earth, and Uranus, the sky...

- Shall raise a helper, the dear son of a bull reared by ZeusZeusIn the ancient Greek religion, Zeus was the "Father of Gods and men" who ruled the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father ruled the family. He was the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. His Roman counterpart is Jupiter and his Etruscan counterpart is Tinia.Zeus was the child of Cronus...

- Who on all the Gauls shall bring a day of destruction.

Pausanius adds that by "son of a bull" the oracle "meant Attalus, king of Pergamon, who was styled bull-horned". On the acropolis of Pergamon was erected a triumphal monument, which included the famous sculpture the Dying Gaul

Dying Gaul

The Dying Gaul , formerly known as the Dying Gladiator, is an ancient Roman marble copy of a lost Hellenistic sculpture that is thought to have been executed in bronze, which was commissioned some time between 230 BC and 220 BC by Attalus I of Pergamon to celebrate his victory over the Celtic...

, commemorating this battle.

Conquests in Seleucid Asia Minor

Several years after the first victory over the Gauls, Pergamon was again attacked by the Gauls together with their ally Antiochus HieraxAntiochus Hierax

Antiochus Hierax , or Antiochus III, , so called from his grasping and ambitious character, was the younger son of Antiochus II and Laodice I and separatist leader in the Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom, who ruled as king of Syria during his brother's reign.On the death of his father, in 246 BCE,...

, the younger brother of Seleucus II Callinicus

Seleucus II Callinicus

Seleucus II Callinicus or Pogon , was a ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, who reigned from 246 to 225 BC...

, and ruler of Seleucid Asia Minor from his capital at Sardis

Sardis

Sardis or Sardes was an ancient city at the location of modern Sart in Turkey's Manisa Province...

. Attalus defeated the Gauls and Antiochus at the battle of Aphrodisium and again at a second battle in the east. Subsequent battles were fought and won against Antiochus alone: in Hellespontine Phrygia

Phrygia

In antiquity, Phrygia was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now modern-day Turkey. The Phrygians initially lived in the southern Balkans; according to Herodotus, under the name of Bryges , changing it to Phruges after their final migration to Anatolia, via the...

, where Antiochus was perhaps seeking refuge with his father-in law, Ziaelas the king of Bithynia

Bithynia

Bithynia was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor, adjoining the Propontis, the Thracian Bosporus and the Euxine .-Description:...

; near Sardis in the spring of 228 BC; and, in the final battle of the campaign, further south in Caria

Caria

Caria was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there...

on the banks of the Harpasus, a tributary of the Maeander.

As a result of these victories, Attalus gained control over all of Seleucid Asia Minor north of the Taurus Mountains

Taurus Mountains

Taurus Mountains are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, dividing the Mediterranean coastal region of southern Turkey from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğirdir in the west to the upper reaches of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the east...

. He was able to hold onto these gains in the face of repeated attempts by Seleucus III Ceraunus

Seleucus III Ceraunus

Seleucus III Soter, called Seleucus Ceraunus , was a ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Kingdom, the eldest son of Seleucus II Callinicus and Laodice II. His birth name was Alexander and was named after his great uncle the Seleucid official Alexander...

, eldest son and successor of Seleucus II, to recover the lost territory, culminating in Seleucus III himself crossing the Taurus, only to be assassinated by members of his army in 223 BC. Achaeus

Achaeus (general)

Achaeus was a general and later a separatist ruler of part of the Greek Seleucid kingdom. He was the son of Andromachus, whose sister Laodice II, married Seleucus Callinicus, the father of Antiochus III the Great. Achaeus himself married Laodice of Pontus, one of the daughters to Laodice and...

, who had accompanied Seleucus III, assumed control of the army. He was offered and refused the kingship in favor of Seleucus III's younger brother Antiochus III the Great

Antiochus III the Great

Antiochus III the Great Seleucid Greek king who became the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire as a youth of about eighteen in 223 BC. Antiochus was an ambitious ruler who ruled over Greater Syria and western Asia towards the end of the 3rd century BC...

, who then made Achaeus governor of Seleucid Asia Minor north of the Taurus. Within two years Achaeus had recovered all the lost Seleucid territories, "shut up Attalus within the walls of Pergamon", and assumed the title of king.

After a period of peace, in 218 BC, while Achaeus was involved in an expedition to Selge south of the Taurus, Attalus, with some Thracian Gauls, recaptured his former territories. However Achaeus returned from victory in Selge in 217 BC and resumed hostilities with Attalus.

Under a treaty of alliance with Attalus, Antiochus crossed the Taurus in 216 BC, attacked Achaeus and besieged Sardis, and in 214 BC, the second year of the siege, was able to take the city. However the citadel remained under Achaeus' control. Under the pretense of a rescue, Achaeus was finally captured and put to death, and the citadel surrendered. By 213 BC, Antiochus had regained control of all of his Asiatic provinces.

First Macedonian War

Thwarted in the east, Attalus now turned his attention westward. Perhaps because of concern for the ambitions of Philip V of MacedonPhilip V of Macedon

Philip V was King of Macedon from 221 BC to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of Rome. Philip was attractive and charismatic as a young man...

, Attalus had sometime before 219 BC become allied with Philip's enemies the Aetolian League

Aetolian League

The Aetolian League was a confederation of tribal communities and cities in ancient Greece centered on Aetolia in central Greece. It was established, probably during the early Hellenistic era, in opposition to Macedon and the Achaean League. Two annual meetings were held in Thermika and Panaetolika...

, a union of Greek states in Aetolia

Aetolia

Aetolia is a mountainous region of Greece on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, forming the eastern part of the modern prefecture of Aetolia-Acarnania.-Geography:...

in central Greece, having funded the fortification of Elaeus, an Aetolian stronghold in Calydon

Calydon

Calydon was an ancient Greek city in Aetolia, situated on the west bank of the river Evenus. According to Greek mythology, the city took its name from its founder Calydon, son of Aetolus. Close to the city stood Mount Zygos, the slopes of which provided the setting for the hunt of the Calydonian...

ia, near the mouth of the river Acheloos

Acheloos River

The Achelous , also Acheloos, is a river in western Greece. It formed the boundary between Acarnania and Aetolia of antiquity. It empties into the Ionian Sea...

.

Philip's alliance with Hannibal of Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

in 215 BC also caused concern in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

, then involved in the Second Punic War

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War, also referred to as The Hannibalic War and The War Against Hannibal, lasted from 218 to 201 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean. This was the second major war between Carthage and the Roman Republic, with the participation of the Berbers on...

. In 211 BC, a treaty was signed between Rome and the Aetolian League, a provision of which allowed for the inclusion of certain allies of the League, Attalus being one of these. Attalus was elected one of the two strategoi

Strategos

Strategos, plural strategoi, is used in Greek to mean "general". In the Hellenistic and Byzantine Empires the term was also used to describe a military governor...

(generals) of the Aetolian League, and in 210 BC his troops probably participated in capturing the island of Aegina

Aegina

Aegina is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of Aeacus, who was born in and ruled the island. During ancient times, Aegina was a rival to Athens, the great sea power of the era.-Municipality:The municipality...

, acquired by Attalus as his base of operations in Greece.

In the following spring (209 BC), Philip marched south into Greece. Under command of Pyrrhias, Attalus' colleague as strategos, the allies lost two battles at Lamia

Lamia (city)

Lamia is a city in central Greece. The city has a continuous history since antiquity, and is today the capital of the regional unit of Phthiotis and of the Central Greece region .-Name:...

. Attalus himself went to Greece in July and was joined on Aegina by the Roman proconsul

Proconsul

A proconsul was a governor of a province in the Roman Republic appointed for one year by the senate. In modern usage, the title has been used for a person from one country ruling another country or bluntly interfering in another country's internal affairs.-Ancient Rome:In the Roman Republic, a...

P. Sulpicius Galba

Publius Sulpicius Galba Maximus

Publius Sulpicius Galba Maximus was a consul of Rome in 211 BC, when he defended the city against the surprise attack by Hannibal.He was proconsul in Greece from 210 to 206, continuing the First Macedonian War against Philip V of Macedon...

who wintered there. The following summer (208 BC) the combined fleet of thirty-five Pergamene and twenty-five Roman ships failed to take Lemnos

Lemnos

Lemnos is an island of Greece in the northern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos peripheral unit, which is part of the North Aegean Periphery. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Myrina...

, but occupied and plundered the countryside of the island of Peparethos (Skopelos

Skopelos

Skopelos , ancient Peparethos or Peparethus , is a Greek island in the western Aegean Sea. Skopelos is one of several islands which comprise the Northern Sporades island group. The island is located east of mainland Greece, northeast of the island of Euboea and is part of the Thessaly Periphery....

), both Macedonian possessions. Attalus and Sulpicius then attended a meeting in Heraclea Trachinia of the Council of the Aetolians, at which the Roman argued against making peace with Philip.

When hostilities resumed, they sacked both Oreus

Oreus

Oreus was a town in northern Euboea. Demosthenes describes its conquest by Philip II of Macedon in the Third Philippic....

, on the northern coast of Euboea

Euboea

Euboea is the second largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. The narrow Euripus Strait separates it from Boeotia in mainland Greece. In general outline it is a long and narrow, seahorse-shaped island; it is about long, and varies in breadth from to...

and Opus

Opus, Greece

Opus , in Ancient Greece, the chief city of Opuntian or Eastern Locris. It was located on the coast of mainland Greece opposite Euboea, perhaps at modern Atalandi...

, the chief city of eastern Locris

Locris

Locris was a region of ancient Greece, the homeland of the Locrians, made up of three distinct districts.-Locrian tribe:...

. The spoils from Oreus had been reserved for Sulpicius, who returned there, while Attalus stayed to collect the spoils from Opus. With their forces divided, Philip attacked Opus. Attalus, caught by surprise, was barely able to escape to his ships.

Attalus was now forced to return to Asia, for he had learned at Opus that, at the instigation of Philip, Prusias I

Prusias I of Bithynia

Prusias I Cholus was a king of Bithynia...

king of Bithynia, related to Philip by marriage, was moving against Pergamon. Soon after, the Romans also abandoned Greece to concentrate their forces against Hannibal, their objective of preventing Philip from aiding Hannibal having been achieved. In 206 BC the Aetolians sued for peace on conditions imposed by Philip. A treaty was drawn up at Phoenice in 205 BC, formally ending the First Macedonian War

First Macedonian War

The First Macedonian War was fought by Rome, allied with the Aetolian League and Attalus I of Pergamon, against Philip V of Macedon, contemporaneously with the Second Punic War against Carthage...

. Attalus was included as an adscriptus on the side of Rome. He retained Aegina, but had accomplished little else. Since Prusias was also included in the treaty, the war between Attalus and Prusias must also have ended by that time.

Introduction of the cult of the Magna Mater to Rome

In 205 BC, following the "Peace of Phoenice", Rome turned to Attalus, as its only friend in Asia, for help concerning a religious matter. An unusual number of meteor showers caused concern in Rome, and an inspection was made of the Sibylline BooksSibylline Books

The Sibylline Books or Libri Sibyllini were a collection of oracular utterances, set out in Greek hexameters, purchased from a sibyl by the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, and consulted at momentous crises through the history of the Republic and the Empire...

, which discovered verses saying that if a foreigner were to make war on Italy, he could be defeated if the Magna Idaea, the Mother Goddess, associated with Mount Ida

Mount Ida

In Greek mythology, two sacred mountains are called Mount Ida, the "Mountain of the Goddess": Mount Ida in Crete; and Mount Ida in the ancient Troad region of western Anatolia which was also known as the Phrygian Ida in classical antiquity and is the mountain that is mentioned in the Iliad of...

in Phrygia

Phrygia

In antiquity, Phrygia was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now modern-day Turkey. The Phrygians initially lived in the southern Balkans; according to Herodotus, under the name of Bryges , changing it to Phruges after their final migration to Anatolia, via the...

, were brought to Rome. Hoping to bring about a speedy conclusion to the war with Hannibal, a distinguished delegation, led by M. Valerius Laevinus, was dispatched to Pergamon, to seek Attalus' aid. According to Livy

Livy

Titus Livius — known as Livy in English — was a Roman historian who wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, "Chapters from the Foundation of the City," covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome well before the traditional foundation in 753 BC...

, Attalus received the delegation warmly, and "handed over to them the sacred stone which the natives declared to be 'the Mother of the Gods', and bade them carry it to Rome." In Rome the goddess became known as the Magna Mater.

Macedonian hostilities of 201 BC

Prevented by the treaty of Phoenice from expansion in the east, Philip set out to extend his power in the AegeanAegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

and in Asia Minor. In the spring of 201 BC he took Samos

Samos Island

Samos is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of Asia Minor, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate regional unit of the North Aegean region, and the only municipality of the regional...

and the Egyptian

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

fleet stationed there. He then besieged Chios

Chios

Chios is the fifth largest of the Greek islands, situated in the Aegean Sea, seven kilometres off the Asia Minor coast. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. The island is noted for its strong merchant shipping community, its unique mastic gum and its medieval villages...

to the north. These events caused Attalus, allied with Rhodes

Rhodes

Rhodes is an island in Greece, located in the eastern Aegean Sea. It is the largest of the Dodecanese islands in terms of both land area and population, with a population of 117,007, and also the island group's historical capital. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within...

, Byzantium

Byzantium

Byzantium was an ancient Greek city, founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king Byzas . The name Byzantium is a Latinization of the original name Byzantion...

and Cyzicus

Cyzicus

Cyzicus was an ancient town of Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peninsula , a tombolo which is said to have originally been an island in the Sea of Marmara only to be connected to the mainland in historic...

, to enter the war. A large naval battle occurred in the strait between Chios and the mainland, just southwest of Erythrae

Erythrae

Erythrae or Erythrai later Litri, was one of the twelve Ionian cities of Asia Minor, situated 22 km north-east of the port of Cyssus , on a small peninsula stretching into the Bay of Erythrae, at an equal distance from the mountains Mimas and Corycus, and directly opposite the island of Chios...

. According to Polybius

Polybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

, fifty-three decked warships and over one hundred and fifty smaller warships, took part on the Macedonian side, with sixty-five decked warships and a number of smaller warships on the allied side. During the battle Attalus, having become isolated from his fleet and pursued by Philip, was forced to run his three ships ashore, narrowly escaping by spreading various royal treasures on the decks of the grounded ships, causing his pursuers to abandon the pursuit in favor of plunder.

The same year, Philip invaded Pergamon; although unable to take the easily defended city, in part due to precautions taken by Attalus to provide for additional fortifications, he demolished the surrounding temples and altars.

Meanwhile, Attalus and Rhodes sent envoys to Rome, to register their complaints against Philip.

Second Macedonian War

In 200 BC, Attalus became involved in the Second Macedonian WarSecond Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. The result was the defeat of Philip who was forced to abandon all his possessions in Greece...

. Acarnania

Acarnania

Acarnania is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today it forms the western part of the prefecture of Aetolia-Acarnania. The capital...

ns with Macedonian support invaded Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

, causing Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

, which had previously maintained its neutrality, to seek help from the enemies of Philip. Attalus, with his fleet at Aegina, received an embassy from Athens, to come to the city for consultations. A few days later, he learned that Roman ambassadors were also at Athens, and decided to go there at once. His reception at Athens was extraordinary. Polybius writes:

Sulpicius Galba, now consul

Consul

Consul was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic and an appointive office under the Empire. The title was also used in other city states and also revived in modern states, notably in the First French Republic...

, convinced Rome to declare war on Philip and asked Attalus to meet up with the Roman fleet and again conduct a naval campaign, harassing Macedonian possessions in the Aegean. In the spring of 199 BC, the combined Pergamon and Roman fleets took Andros

Andros

Andros, or Andro is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, approximately south east of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . Its surface is for the most part mountainous, with many fruitful and well-watered valleys. The area is...

in the Cyclades

Cyclades

The Cyclades is a Greek island group in the Aegean Sea, south-east of the mainland of Greece; and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name refers to the islands around the sacred island of Delos...

, the spoils going to the Romans and the island to Attalus. From Andros they sailed south, made a fruitless attack on another Cycladic island, Kithnos, turned back north, scavenged the fields of Skiathos

Skiathos

Skiathos is a small Greek island in the northwest Aegean Sea. Skiathos is the westernmost island in the Northern Sporades group, east of the Pelion peninsula in Magnesia on the mainland, and west of the island of Skopelos.-Geography:...

off the coast of Magnesia

Magnesia Prefecture

Magnesia Prefecture was one of the prefectures of Greece. Its capital was Volos. It was established in 1899 from the Larissa Prefecture. The prefecture was disbanded on 1 January 2011 by the Kallikratis programme, and split into the peripheral units of Magnesia and the Sporades.The toponym is...

, for food, and continued north to Mende

Mende (Greece)

Mende was an ancient Greek city located in the western coast of Pallene peninsula in Chalkidiki facing the coast of Pieria across the narrow Thermaic Gulf near the modern town of Kalandra.- Ancient History :...

, where the fleets were wracked by storm. On land they were repulsed at Cassandrea, suffering heavy loss. They continued northeast along the Macedonian coast to Acanthus

Acanthus (Greece)

Ierissos Modern Greek: or Acanthus was an ancient Greek city on the Athos peninsula. It was located on the north-east side of Akti, on the most eastern peninsula of Chalcidice...

, which they sacked, after which they returned to Euboea, their vessels laden with spoils. On their return, the two leaders went to Heraclea to meet with the Aetolians, who under the terms of their treaty, had asked Attalus for a thousand soldiers. He refused, citing the Aetolians' own refusal to honor Attalus' request to attack Macedonia during Philip's attack on Pergamon two years earlier. Resuming operations, Attalus and the Romans attacked but failed to take Oreus and, deciding to leave a small force to invest it, attacked across the straight in Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

. When they returned to Oreus, they again attacked, this time successfully, the Romans taking the captives, Attalus the city. The campaigning season now over, Attalus attended the Eleusinian Mysteries

Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries were initiation ceremonies held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at Eleusis in ancient Greece. Of all the mysteries celebrated in ancient times, these were held to be the ones of greatest importance...

and then returned to Pergamon having been away for over two years.

In the spring of 198 BC, Attalus returned to Greece with twenty-three quinquereme

Quinquereme

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, superseding the trireme and transforming naval warfare. Ships became increasingly bigger and heavier, including some of the largest wooden ships ever constructed...

s joining a fleet of twenty Rhodian decked warships at Andros, to complete the conquest of Euboea begun the previous year. Soon joined by the Romans, the combined fleets took Eretria

Eretria

Erétria was a polis in Ancient Greece, located on the western coast of the island of Euboea, south of Chalcis, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow Euboean Gulf. Eretria was an important Greek polis in the 6th/5th century BC. However, it lost its importance already in antiquity...

and later Carystus

Carystus

Carystus ; was an ancient city-state on Euboea. In the Iliad it is controlled by the Abantes. By the time of Thucydides it was inhabited by Dryopians.- Persian War :...

. Thus, the allies controlled all of Euboea except for Chalcis

Chalcis

Chalcis or Chalkida , the chief town of the island of Euboea in Greece, is situated on the strait of the Evripos at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from antiquity and is derived from the Greek χαλκός , though there is no trace of any mines in the area...

. The allied fleet then sailed for Cenchreae in preparation for an attack on Corinth

Corinth

Corinth is a city and former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Corinth, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

. Meanwhile, the new Roman consul for that year, Titus Quinctius Flamininus

Titus Quinctius Flamininus

Titus Quinctius Flamininus was a Roman politician and general instrumental in the Roman conquest of Greece.Member of the gens Quinctia, and brother to Lucius Quinctius Flamininus, he served as a military tribune in the Second Punic war and in 205 BC he was appointed propraetor in Tarentum...

, had learned that the Achaean League

Achaean League

The Achaean League was a Hellenistic era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese, which existed between 280 BC and 146 BC...

, allies of Macedon, had had a change in leadership which favored Rome. With the hope of inducing the Achaeans to abandon Philip and join the allies, envoys were sent, including Attalus himself, to Sicyon

Sicyon

Sikyon was an ancient Greek city situated in the northern Peloponnesus between Corinth and Achaea on the territory of the present-day prefecture of Corinthia...

, where they offered the incorporation of Corinth into the Achaean League. Attalus apparently so impressed the Sicyonians, that they erected a colossal statue of him in their market place and instituted sacrifices in his honor. A meeting of the League was convened and after a heated debate and the withdrawal of some of delegates the rest agreed to join the alliance. Attalus led his army from Cenchreae (now controlled by the allies) through the Isthmus and attached Corinth from the north, controlling the access to Lechaeum, the Corinthian port on the Gulf of Corinth, the Romans attacked from the east controlling the approaches to Cenchreae, with the Achaeans attacking from the west controlling the access to the city via the Sicyonian gate. However the city held, and when Macedonian reinforcements arrived, the siege was abandoned. The Achaeans were dismissed, the Romans left for Corcyra, while Attalus sailed for Piraeus

Piraeus

Piraeus is a city in the region of Attica, Greece. Piraeus is located within the Athens Urban Area, 12 km southwest from its city center , and lies along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf....

.

Early in 197 BC, Flamininus, summoned Attalus to join him at Elateia

Elateia

Elateia was an ancient Greek city of Phocis, and the most important place in that region after Delphi. It is also a modern-day town that is a former municipality in the southeastern part of Phthiotis. Since the 2011 local government reform, it is a municipal unit of the municipality...

(now in Roman hands) and from there they traveled together to attend a Boeotia

Boeotia

Boeotia, also spelled Beotia and Bœotia , is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. It was also a region of ancient Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, the second largest city being Thebes.-Geography:...

n council in Thebes to discuss which side Boeotia would take in the war. At the council Attalus spoke first, reminding the Boeotians of the many things he and his ancestors had done for them, but during his address he stopped talking and collapsed, with one side of his body paralyzed. Attalus was taken back to Pergamon, where he died around the time of the Battle of Cynoscephalae

Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Philip V.- Prelude :...

, which brought about the end of the Second Macedonian War.

Family

Attalus married Apollonis, from CyzicusCyzicus

Cyzicus was an ancient town of Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peninsula , a tombolo which is said to have originally been an island in the Sea of Marmara only to be connected to the mainland in historic...

. They had four sons, Eumenes

Eumenes II

Eumenes II of Pergamon was king of Pergamon and a member of the Attalid dynasty. The son of king Attalus I and queen Apollonis, he followed in his father's footsteps and collaborated with the Romans to oppose first Macedonian, then Seleucid expansion towards the Aegean, leading to the defeat of...

, Attalus, Philetaerus and Athenaeus (after Apollonis' father). Polybius

Polybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

describes Apollonis as "a woman who for many reasons deserves to be remembered, and with honor. Her claims upon a favourable recollection are that, though born of a private family, she became a queen, and retained that exalted rank to the end of her life, not by the use of meretricious fascinations, but by the virtue and integrity of her conduct in private and public life alike. Above all, she was the mother of four sons with whom she kept on terms of the most perfect affection and motherly love to the last day of her life."

The filial "affection" of the brothers as well as their upbringing is remarked on by several ancient sources. A decree of Antiochus IV praises "king Attalus and queen Apollonis … because of their virtue and goodness, which they preserved for their sons, managing their education in this way wisely and well." An inscription at Pergamon represents Apollonis as saying that "she always considered herself blessed and gave thanks to the gods, not for wealth or empire, but because she saw her three sons guarding the eldest and him reigning without fear among those who were armed." When Attalus died in 197 BC at the age of 72, he was succeeded by his eldest son Eumenes II. Polybius, describing Attalus' life says "and what is more remarkable than all, though he left four grown-up sons, he so well settled the question of succession, that the crown was handed down to his children's children without a single dispute."

Primary sources

- LivyLivyTitus Livius — known as Livy in English — was a Roman historian who wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, "Chapters from the Foundation of the City," covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome well before the traditional foundation in 753 BC...

, History of Rome, Rev. Canon Roberts (translator), Ernest Rhys (Ed.); (1905) London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd. - PausaniasPausanias (geographer)Pausanias was a Greek traveler and geographer of the 2nd century AD, who lived in the times of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his Description of Greece , a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from firsthand observations, and is a crucial link between classical...

, Description of Greece, Books I–II, (Loeb Classical LibraryLoeb Classical LibraryThe Loeb Classical Library is a series of books, today published by Harvard University Press, which presents important works of ancient Greek and Latin Literature in a way designed to make the text accessible to the broadest possible audience, by presenting the original Greek or Latin text on each...

) translated by W. H. S. Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University PressHarvard University PressHarvard University Press is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. In 2005, it published 220 new titles. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. Its current director is William P...

; London, William Heinemann Ltd. (1918) ISBN 0-674-99104-4. - PolybiusPolybiusPolybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

, Histories, Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (translator); London, New York. Macmillan (1889); Reprint Bloomington (1962). - StraboStraboStrabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

, Geography, Books 13–14, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924) ISBN 0-674-99246-6.