Athanasius Kircher

Encyclopedia

Athanasius Kircher (sometimes erroneously spelled Kirchner) was a 17th century German

Jesuit

scholar who published around 40 works, most notably in the fields of oriental studies

, geology

, and medicine

. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci

for his enormous range of interests, and has been honoured with the title "master of a hundred arts".

Kircher was the most famous "decipherer" of hieroglyphs of his day, although most of his assumptions and "translations" in this field have since been disproved as nonsensical. However, he did make an early study of Egyptian hieroglyphs, correctly establishing the link between the ancient Egyptian language

and the Coptic language

, for which he has been considered the founder of Egyptology

. He was also fascinated with Sinology

, and wrote an encyclopedia of China

, in which he noted the early presence of Nestorian Christians but also attempted to establish more tenuous links with Egypt and Christianity.

Kircher's work with geology included studies of volcano

s and fossil

s. One of the first people to observe microbes through a microscope

, he was thus ahead of his time in proposing that the plague

was caused by an infectious microorganism

and in suggesting effective measures to prevent the spread of the disease. Kircher also displayed a keen interest in technology and mechanical inventions, and inventions attributed to him include a magnetic clock, various automaton

s and the first megaphone

. The invention of the magic lantern

is often misattributed to Kircher, although he did conduct a study of the principles involved in his Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.

A scientific star in his day, towards the end of his life he was eclipsed by the rationalism

of René Descartes

and others. In the late 20th century, however, the aesthetic qualities of his work again began to be appreciated. One modern scholar, Alan Cutler, described Kircher as "a giant among seventeenth-century scholars", and "one of the last thinkers who could rightfully claim all knowledge as his domain". Another scholar, Edward W. Schmidt, referred to Kircher as "the last Renaissance man

".

, Buchonia

, near Fulda

, currently Hesse

, Germany

. From his birthplace he took the epithets Bucho, Buchonius and Fuldensis which he sometimes added to his name. He attended the Jesuit College in Fulda from 1614 to 1618, when he joined the order himself as a seminarian

.

The youngest of nine children, Kircher studied volcanoes for his passion of rocks and eruptions. He was taught Hebrew by a rabbi

in addition to his studies at school. He studied philosophy

and theology

at Paderborn

, but fled to Cologne

in 1622 to escape advancing Protestant forces. On the journey, he narrowly escaped death after falling through the ice crossing the frozen Rhine— one of several occasions on which his life was endangered. Later, travelling to Heiligenstadt

, he was caught and nearly hanged

by a party of Protestant soldiers.

From 1622 to 1624 Kircher stayed in Koblenz as a teacher. At Heiligenstadt, he taught mathematics

, Hebrew and Syriac

, and produced a show of fireworks and moving scenery for the visiting Elector

Archbishop of Mainz, showing early evidence of his interest in mechanical devices

. He joined the priesthood in 1628 and became professor of ethics

and mathematics

at the University of Würzburg

, where he also taught Hebrew and Syriac. From 1628, he also began to show an interest in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Kircher published his first book (the Ars Magnesia, reporting his research on magnetism

) in 1631, but the same year he was driven by the continuing Thirty Years' War

to the papal University of Avignon

in France

. In 1633, he was called to Vienna

by the emperor

to succeed Kepler

as Mathematician to the Habsburg

court. On the intervention of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc

, the order was rescinded and he was sent instead to Rome

to continue with his scholarly work, but he had already set off for Vienna.

On the way, his ship was blown off-course and he arrived in Rome before he knew of the changed decision. He based himself in the city for the rest of his life, and from 1638, he taught mathematics, physics

and oriental languages at the Collegio Romano for several years before being released to devote himself to research. He studied malaria

and the plague

, amassing a collection of antiquities

, which he exhibited along with devices of his own creation in the Museum Kircherianum.

In 1661, Kircher discovered the ruins of a church said to have been constructed by Constantine on the site of Saint Eustace

's vision of Jesus Christ in a stag's horns. He raised money to pay for the church’s reconstruction as the Santuario della Mentorella, and his heart was buried in the church on his death.

, geology

, and music theory

. His syncretic

approach paid no attention to the boundaries between disciplines which are now conventional: his Magnes, for example, was ostensibly a discussion of magnetism

, but also explored other forms of attraction such as gravity and love

. Perhaps Kircher's best-known work today is his Oedipus Aegyptiacus

(1652–54) a vast study of Egyptology and comparative religion

. His books, written in Latin

, had a wide circulation in the 17th century, and they contributed to the dissemination of scientific information to a broader circle of readers. But Kircher is not now considered to have made any significant original contributions, although a number of discoveries and inventions (e.g., the magic lantern

) have sometimes been mistakenly attributed to him.

of Egyptian hieroglyphics

dates from AD 394, after which all knowledge of hieroglyphics was lost. Until Thomas Young

and Jean-François Champollion

found the key to hieroglyphics in the 19th century, the main authority was the 4th century Greek grammarian Horapollon

, whose chief contribution was the misconception that hieroglyphics were "picture writing" and that future translators should look for symbolic meaning in the pictures. The first modern study of hieroglyphics came with Piero Valeriano Bolzani

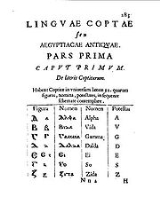

's nonsensical Hieroglyphica (1566), but Kircher was the most famous of the "decipherers" between ancient and modern times and the most famous Egyptologist of his day. In his Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta (1643), Kircher called hieroglyphics "this language hitherto unknown in Europe, in which there are as many pictures as letters, as many riddles as sounds, in short as many mazes to be escaped from as mountains to be climbed". While some of his notions are long discredited, portions of his work have been valuable to later scholars, and Kircher helped pioneer Egyptology as a field of serious study.

Kircher's interest in Egyptology began in 1628 when he became intrigued by a collection of hieroglyphs in the library at Speyer

. He learned Coptic

in 1633 and published the first grammar of that language in 1636, the Prodromus coptus sive aegyptiacus. Kircher then broke with Horapollon's interpretation of the language of the hieroglyphs with his Lingua aegyptiaca restituta. Kircher argued that Coptic preserved the last development of ancient Egyptian

. For this Kircher has been considered the true "founder of Egyptology", because his work was conducted "before the discovery of the Rosetta Stone

rendered Egyptian hieroglyphics comprehensible to scholars". He also recognised the relationship between the hieratic

and hieroglyphic scripts.

Between 1650 and 1654, Kircher published four volumes of "translations" of hieroglyphs in the context of his Coptic studies. However, according to Steven Frimmer, "none of them even remotely fitted the original texts". In Oedipus Aegyptiacus

Between 1650 and 1654, Kircher published four volumes of "translations" of hieroglyphs in the context of his Coptic studies. However, according to Steven Frimmer, "none of them even remotely fitted the original texts". In Oedipus Aegyptiacus

, Kircher argued under the impression of the Hieroglyphica that ancient Egyptian

was the language spoken by Adam and Eve

, that Hermes Trismegistus

was Moses

, and that hieroglyphs were occult

symbol

s which "cannot be translated by words, but expressed only by marks, characters and figures." This led him to translate simple hieroglyphic texts now known to read as dd Wsr ("Osiris says") as "The treachery of Typhon ends at the throne of Isis; the moisture of nature is guarded by the vigilance of Anubis".

Although his approach to deciphering the texts was based on a fundamental misconception, Kircher did pioneer serious study of hieroglyphs, and the data which he collected were later used by Champollion in his successful efforts to decode the script. Kircher himself was alive to the possibility of the hieroglyphs constituting an alphabet

; he included in his proposed system (incorrect) derivations of the Greek alphabet

from 21 hieroglyphs. However, according to Joseph MacDonnell, it was "because of Kircher's work that scientists knew what to look for when interpreting the Rosetta stone". Another scholar of ancient Egypt, Erik Iverson, concluded:

Kircher was also actively involved in the erection of obelisks in Roman squares, often adding fantastic "hieroglyphs" of his own design in the blank areas that are now puzzling to modern scholars.

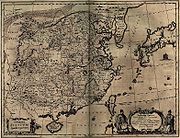

Kircher had an early interest in China

Kircher had an early interest in China

, telling his superior in 1629 that he wished to become a missionary

to the country. In 1667 he published a treatise whose full title was China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae and artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, and which is commonly known simply as China Illustrata, i.e. "China Illustrated". It was a work of encyclopedic breadth, combining material of unequal quality, from accurate cartography

to mythical elements, such as dragon

s. The work drew heavily on the reports of Jesuits working in China, in particular Michael Boym and Martino Martini

.

China Illustrata emphasized the Christian elements of Chinese history, both real and imagined: the book noted the early presence of Nestorian Christians (with a Latin translation of the Nestorian Stele

of Xi'an

provided by Boym and his Chinese collaborator, Andrew Zheng), but also claimed that the Chinese were descended from the sons of Ham

, that Confucius

was Hermes Trismegistus/Moses and that the Chinese character

s were abstracted hieroglyphs.

In Kircher's system, ideogram

s were inferior to hieroglyphs because they referred to specific ideas rather than to mysterious complexes of ideas, while the signs of the Maya and Aztec

s were yet lower pictogram

s which referred only to objects. Umberto Eco

comments that this idea reflected and supported the European attitude to the Chinese and native American civilizations;

"China was presented not as an unknown barbarian to be defeated but as a prodigal son who should return to the home of the common father". (p. 69)

— following the Counter-Reformation

, allegorical interpretation

was giving way to the study of the Old Testament as literal truth among Scriptural scholars. Kircher analyzed the dimensions of the Ark; based on the number of species known to him (excluding insects and other forms thought to arise spontaneously

), he calculated that overcrowding would not have been a problem. He also discussed the logistics of the Ark voyage, speculating on whether extra livestock was brought to feed carnivores and what the daily schedule of feeding and caring for animals must have been.

in 1666; sent to him by Johannes Marcus Marci in the hope of Kircher being able to decipher it. The manuscript remained in the Collegio Romano until Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

annexed the Papal States

in 1870, though scepticism as to the authenticity of the story and of the origin of the manuscript itself exists. In his Polygraphia nova (1663), Kircher proposed an artificial universal language

.

On a visit to southern Italy in 1638, the ever-curious Kircher was lowered into the crater

On a visit to southern Italy in 1638, the ever-curious Kircher was lowered into the crater

of Vesuvius, then on the brink of eruption, in order to examine its interior. He was also intrigued by the subterranean rumbling which he heard at the Strait of Messina

. His geological and geographical investigations culminated in his Mundus Subterraneus of 1664, in which he suggested that the tide

s were caused by water moving to and from a subterranean ocean

.

Kircher was also puzzled by fossil

s. He understood that some were the remains of animal

s which had turned to stone, but ascribed others to human invention or to the spontaneous generative force of the earth

. He ascribed large bones to giant races of humans. Not all the objects which he was attempting to explain were in fact fossils, hence the diversity of explanations. He interpreted mountain ranges as the Earth's skeletal structures exposed by weathering.

Kircher took a notably modern approach to the study of disease

Kircher took a notably modern approach to the study of disease

s, as early as 1646 using a microscope

to investigate the blood

of plague

victims. In his Scrutinium Pestis of 1658, he noted the presence of "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood, and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganism

s. The conclusion was correct, although it is likely that what he saw were in fact red

or white

blood cell

s and not the plague agent, Yersinia pestis

. He also proposed hygienic

measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine

, burning clothes worn by the infected and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germ

s.

In 1646, Kircher published Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, on the subject of the display of images on a screen using an apparatus similar to the magic lantern

In 1646, Kircher published Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, on the subject of the display of images on a screen using an apparatus similar to the magic lantern

as developed by Christiaan Huygens and others. Kircher described the construction of a "catotrophic lamp" that used reflection to project images on the wall of a darkened room. Although Kircher did not invent the device, he made improvements over previous models, and suggested methods by which exhibitors could use his device. Much of the significance of his work arises from Kircher's rational approach towards the demystification of projected images. Previously such images had been used in Europe to mimic supernatural appearances (Kircher himself cites the use of displayed images by the rabbis in the court of King Solomon). Kircher stressed that exhibitors should take great care to inform spectators that such images were purely naturalistic, and not magical in origin.

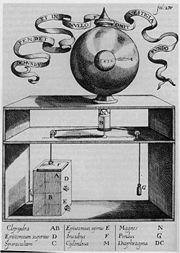

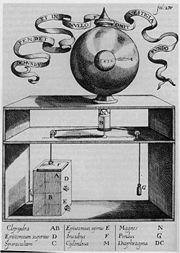

Kircher also constructed a magnetic

clock, the mechanism of which he explained in his Magnes (1641). The device had originally been invented by another Jesuit, Fr. Linus of Liege, and was described by an acquaintance of Line's in 1634. Kircher's patron Peiresc had claimed that the clock's motion supported the Copernican

cosmological model, the argument being that the magnetic sphere in the clock was caused to rotate by the magnetic force of the sun

. Kircher's model disproved the hypothesis, showing that the motion could be produced by a water clock

in the base of the device. Although Kircher wrote against the Copernican

model in his Magnes, supporting instead that of Tycho Brahe

, his later Itinerarium extaticum (1656, revised 1671), presented several systems — including the Copernican — as distinct possibilities. The clock has been reconstructed by Caroline Bouguereau in collaboration with Michael John Gorman and is on display at the Green Library at Stanford University..

The Musurgia Universalis (1650) sets out Kircher's views on music

: he believed that the harmony

of music reflected the proportions of the universe

. The book includes plans for constructing water-powered automatic organs, notations

of birdsong

and diagrams of musical instrument

s. One illustration shows the differences between the ear

s of humans and other animals. In Phonurgia Nova (1673) Kircher considered the possibilities of transmitting music to remote places.

Other machines designed by Kircher include an aeolian harp

, automaton

s such as a statue which spoke and listened via a speaking tube

, a perpetual motion machine, and a Katzenklavier

("cat piano"). This last of these would have driven spikes into the tails of cats, which would yowl to specified pitches

, although Kircher is not known to have actually constructed the instrument.

). His methods and diagrams are discussed in Ars Magna Sciendi, sive Combinatoria (sic).

s and research he added information gleaned from his correspondence with over 760 scientists, physicians and above all his fellow Jesuits in all parts of the globe. The Encyclopædia Britannica

calls him a "one-man intellectual clearing house". His works, illustrated to his orders, were extremely popular, and he was the first scientist to be able to support himself through the sale of his books. Towards the end of his life his stock fell, as the rationalist

Cartesian

approach began to dominate (Descartes himself described Kircher as "more quacksalver than savant").

:

He added that "Kircher's postmodern qualities include his subversiveness, his celebrity, his technomania and his bizarre eclecticism

". In Robert Graham Irwin

's For Lust of Knowing

, Kircher is called "one of the last scholars aspiring to know everything", with Kircher's contemporary countryman Gottfried Leibniz

cited as the probable "last" such scholar.

As few of Kircher's works have been translated, the contemporary emphasis has been on their aesthetic qualities rather than their actual content, and a succession of exhibitions have highlighted the beauty of their illustrations. Historian Anthony Grafton has said that "the staggeringly strange dark continent of Kircher's work [is] the setting for a Borges story that was never written", while Umberto Eco

has written about Kircher in his novel The Island of the Day Before

, as well as in his non-fiction works The Search for the Perfect Language and Serendipities. The contemporary artist Cybèle Varela

has paid tribute to Kircher in her exhibition Ad Sidera per Athanasius Kircher, held in the Collegio Romano, in the same place where the Museum Kircherianum was.

The Museum of Jurassic Technology

in Los Angeles

has a hall dedicated to the life of Kircher. The Athanasius Kircher Society had a weblog devoted to unusual ephemera, which very occasionally relate to Kircher. His ethnographic collection is in the Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography

in Rome.

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

Jesuit

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

scholar who published around 40 works, most notably in the fields of oriental studies

Orientalism

Orientalism is a term used for the imitation or depiction of aspects of Eastern cultures in the West by writers, designers and artists, as well as having other meanings...

, geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, and medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance...

for his enormous range of interests, and has been honoured with the title "master of a hundred arts".

Kircher was the most famous "decipherer" of hieroglyphs of his day, although most of his assumptions and "translations" in this field have since been disproved as nonsensical. However, he did make an early study of Egyptian hieroglyphs, correctly establishing the link between the ancient Egyptian language

Egyptian language

Egyptian is the oldest known indigenous language of Egypt and a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. Written records of the Egyptian language have been dated from about 3400 BC, making it one of the oldest recorded languages known. Egyptian was spoken until the late 17th century AD in the...

and the Coptic language

Coptic language

Coptic or Coptic Egyptian is the current stage of the Egyptian language, a northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century. Egyptian began to be written using the Greek alphabet in the 1st century...

, for which he has been considered the founder of Egyptology

Egyptology

Egyptology is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious practices in the AD 4th century. A practitioner of the discipline is an “Egyptologist”...

. He was also fascinated with Sinology

Sinology

Sinology in general use is the study of China and things related to China, but, especially in the American academic context, refers more strictly to the study of classical language and literature, and the philological approach...

, and wrote an encyclopedia of China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, in which he noted the early presence of Nestorian Christians but also attempted to establish more tenuous links with Egypt and Christianity.

Kircher's work with geology included studies of volcano

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

s and fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

s. One of the first people to observe microbes through a microscope

Microscope

A microscope is an instrument used to see objects that are too small for the naked eye. The science of investigating small objects using such an instrument is called microscopy...

, he was thus ahead of his time in proposing that the plague

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

was caused by an infectious microorganism

Microorganism

A microorganism or microbe is a microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters, or no cell at all...

and in suggesting effective measures to prevent the spread of the disease. Kircher also displayed a keen interest in technology and mechanical inventions, and inventions attributed to him include a magnetic clock, various automaton

Automaton

An automaton is a self-operating machine. The word is sometimes used to describe a robot, more specifically an autonomous robot. An alternative spelling, now obsolete, is automation.-Etymology:...

s and the first megaphone

Megaphone

A megaphone, speaking-trumpet, bullhorn, blowhorn, or loud hailer is a portable, usually hand-held, cone-shaped horn used to amplify a person’s voice or other sounds towards a targeted direction. This is accomplished by channelling the sound through the megaphone, which also serves to match the...

. The invention of the magic lantern

Magic lantern

The magic lantern or Laterna Magica is an early type of image projector developed in the 17th century.-Operation:The magic lantern has a concave mirror in front of a light source that gathers light and projects it through a slide with an image scanned onto it. The light rays cross an aperture , and...

is often misattributed to Kircher, although he did conduct a study of the principles involved in his Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.

A scientific star in his day, towards the end of his life he was eclipsed by the rationalism

Rationalism

In epistemology and in its modern sense, rationalism is "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification" . In more technical terms, it is a method or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive"...

of René Descartes

René Descartes

René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day...

and others. In the late 20th century, however, the aesthetic qualities of his work again began to be appreciated. One modern scholar, Alan Cutler, described Kircher as "a giant among seventeenth-century scholars", and "one of the last thinkers who could rightfully claim all knowledge as his domain". Another scholar, Edward W. Schmidt, referred to Kircher as "the last Renaissance man

Renaissance Man

Renaissance Man is a 1994 comedy film, directed by Penny Marshall, starring Danny DeVito, Gregory Hines, James Remar, and Ed Begley, Jr. It also features Mark Wahlberg in one of his earliest roles....

".

Life

Kircher was born on 2 May in either 1601 or 1602 (he himself did not know) in GeisaGeisa

Geisa is a town in the Wartburgkreis district, in Thuringia, Germany. It is situated in the Rhön Mountains, 26 km northeast of Fulda.The near border with Hesse was the border between West Germany and the GDR during the Cold War...

, Buchonia

Buchonia

Buchonia is a region in Hesse, a state of Germany, where one of the first forestry planning systems was developed by Georg Ludwig Hartig . It was called "Flächenfachwerk". He also wrote in 1791 "Anweisung zur Holzzucht für Förster"-Books:...

, near Fulda

Fulda

Fulda is a city in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district .- Early Middle Ages :...

, currently Hesse

Hesse

Hesse or Hessia is both a cultural region of Germany and the name of an individual German state.* The cultural region of Hesse includes both the State of Hesse and the area known as Rhenish Hesse in the neighbouring Rhineland-Palatinate state...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. From his birthplace he took the epithets Bucho, Buchonius and Fuldensis which he sometimes added to his name. He attended the Jesuit College in Fulda from 1614 to 1618, when he joined the order himself as a seminarian

Seminary

A seminary, theological college, or divinity school is an institution of secondary or post-secondary education for educating students in theology, generally to prepare them for ordination as clergy or for other ministry...

.

The youngest of nine children, Kircher studied volcanoes for his passion of rocks and eruptions. He was taught Hebrew by a rabbi

Rabbi

In Judaism, a rabbi is a teacher of Torah. This title derives from the Hebrew word רבי , meaning "My Master" , which is the way a student would address a master of Torah...

in addition to his studies at school. He studied philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

and theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

at Paderborn

Paderborn

Paderborn is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader, which originates in more than 200 springs near Paderborn Cathedral, where St. Liborius is buried.-History:...

, but fled to Cologne

Cologne

Cologne is Germany's fourth-largest city , and is the largest city both in the Germany Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia and within the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Area, one of the major European metropolitan areas with more than ten million inhabitants.Cologne is located on both sides of the...

in 1622 to escape advancing Protestant forces. On the journey, he narrowly escaped death after falling through the ice crossing the frozen Rhine— one of several occasions on which his life was endangered. Later, travelling to Heiligenstadt

Heiligenstadt

Heiligenstadt may refer to several places:*Heilbad Heiligenstadt, Thuringia, Germany*Heiligenstadt i.OFr. , Bamberg , Bavaria, Germany*Heiligenstadt, Vienna, Austria*Heiligenstadt, part of Neuhaus in Kärnten, Carinthia, Austria...

, he was caught and nearly hanged

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

by a party of Protestant soldiers.

From 1622 to 1624 Kircher stayed in Koblenz as a teacher. At Heiligenstadt, he taught mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, Hebrew and Syriac

Aramaic language

Aramaic is a group of languages belonging to the Afroasiatic language phylum. The name of the language is based on the name of Aram, an ancient region in central Syria. Within this family, Aramaic belongs to the Semitic family, and more specifically, is a part of the Northwest Semitic subfamily,...

, and produced a show of fireworks and moving scenery for the visiting Elector

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

Archbishop of Mainz, showing early evidence of his interest in mechanical devices

Mechanics

Mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of physical bodies when subjected to forces or displacements, and the subsequent effects of the bodies on their environment....

. He joined the priesthood in 1628 and became professor of ethics

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions about morality—that is, concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime, etc.Major branches of ethics include:...

and mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

at the University of Würzburg

University of Würzburg

The University of Würzburg is a university in Würzburg, Germany, founded in 1402. The university is a member of the distinguished Coimbra Group.-Name:...

, where he also taught Hebrew and Syriac. From 1628, he also began to show an interest in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Kircher published his first book (the Ars Magnesia, reporting his research on magnetism

Magnetism

Magnetism is a property of materials that respond at an atomic or subatomic level to an applied magnetic field. Ferromagnetism is the strongest and most familiar type of magnetism. It is responsible for the behavior of permanent magnets, which produce their own persistent magnetic fields, as well...

) in 1631, but the same year he was driven by the continuing Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

to the papal University of Avignon

University of Avignon

The University of Avignon is a French university, based in Avignon. It is under the Academy of Aix and Marseille.-See also:...

in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. In 1633, he was called to Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

by the emperor

Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand II , a member of the House of Habsburg, was Holy Roman Emperor , King of Bohemia , and King of Hungary . His rule coincided with the Thirty Years' War.- Life :...

to succeed Kepler

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

as Mathematician to the Habsburg

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg , also found as Hapsburg, and also known as House of Austria is one of the most important royal houses of Europe and is best known for being an origin of all of the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors between 1438 and 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian Empire and...

court. On the intervention of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc

Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc

Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc was a French astronomer, antiquary and savant who maintained a wide correspondence with scientists and was a successful organizer of scientific inquiry...

, the order was rescinded and he was sent instead to Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

to continue with his scholarly work, but he had already set off for Vienna.

On the way, his ship was blown off-course and he arrived in Rome before he knew of the changed decision. He based himself in the city for the rest of his life, and from 1638, he taught mathematics, physics

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

and oriental languages at the Collegio Romano for several years before being released to devote himself to research. He studied malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

and the plague

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

, amassing a collection of antiquities

Archaeology

Archaeology, or archeology , is the study of human society, primarily through the recovery and analysis of the material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts and cultural landscapes...

, which he exhibited along with devices of his own creation in the Museum Kircherianum.

In 1661, Kircher discovered the ruins of a church said to have been constructed by Constantine on the site of Saint Eustace

Saint Eustace

Saint Eustace, also known as Eustachius or Eustathius, was a legendary Christian martyr who lived in the 2nd century AD. A martyr of that name is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, which, however, judges that the legend recounted about him is "completely fabulous." For that reason...

's vision of Jesus Christ in a stag's horns. He raised money to pay for the church’s reconstruction as the Santuario della Mentorella, and his heart was buried in the church on his death.

Work

Kircher published a large number of substantial books on a very wide variety of subjects, such as EgyptologyEgyptology

Egyptology is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious practices in the AD 4th century. A practitioner of the discipline is an “Egyptologist”...

, geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, and music theory

Music theory

Music theory is the study of how music works. It examines the language and notation of music. It seeks to identify patterns and structures in composers' techniques across or within genres, styles, or historical periods...

. His syncretic

Syncretism

Syncretism is the combining of different beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. The term means "combining", but see below for the origin of the word...

approach paid no attention to the boundaries between disciplines which are now conventional: his Magnes, for example, was ostensibly a discussion of magnetism

Magnetism

Magnetism is a property of materials that respond at an atomic or subatomic level to an applied magnetic field. Ferromagnetism is the strongest and most familiar type of magnetism. It is responsible for the behavior of permanent magnets, which produce their own persistent magnetic fields, as well...

, but also explored other forms of attraction such as gravity and love

Love

Love is an emotion of strong affection and personal attachment. In philosophical context, love is a virtue representing all of human kindness, compassion, and affection. Love is central to many religions, as in the Christian phrase, "God is love" or Agape in the Canonical gospels...

. Perhaps Kircher's best-known work today is his Oedipus Aegyptiacus

Oedipus Aegyptiacus

Oedipus Aegyptiacus is Athanasius Kircher's supreme work of Egyptology.The three full folio tomes of ornate illustrations and diagrams were published in Rome over the period 1652–54...

(1652–54) a vast study of Egyptology and comparative religion

Comparative religion

Comparative religion is a field of religious studies that analyzes the similarities and differences of themes, myths, rituals and concepts among the world's religions...

. His books, written in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, had a wide circulation in the 17th century, and they contributed to the dissemination of scientific information to a broader circle of readers. But Kircher is not now considered to have made any significant original contributions, although a number of discoveries and inventions (e.g., the magic lantern

Magic lantern

The magic lantern or Laterna Magica is an early type of image projector developed in the 17th century.-Operation:The magic lantern has a concave mirror in front of a light source that gathers light and projects it through a slide with an image scanned onto it. The light rays cross an aperture , and...

) have sometimes been mistakenly attributed to him.

Egyptology

The last known exampleThe Graffito of Esmet-Akhom

The Graffito of Esmet-Akhom is the latest known inscription written in Egyptian hieroglyphs. It is inscribed in the temple of Philae in southern Egypt, and was written in 394 AD. It is dated to the Birthday of Osiris, year 110 , which is August 24, 394 AD....

of Egyptian hieroglyphics

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs were a formal writing system used by the ancient Egyptians that combined logographic and alphabetic elements. Egyptians used cursive hieroglyphs for religious literature on papyrus and wood...

dates from AD 394, after which all knowledge of hieroglyphics was lost. Until Thomas Young

Thomas Young (scientist)

Thomas Young was an English polymath. He is famous for having partly deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics before Jean-François Champollion eventually expanded on his work...

and Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion was a French classical scholar, philologist and orientalist, decipherer of the Egyptian hieroglyphs....

found the key to hieroglyphics in the 19th century, the main authority was the 4th century Greek grammarian Horapollon

Horapollon

Horapollon, a Greek grammarian, flourished in the 4th century AD during the reign of Theodosius I.According to the Suda, he wrote commentaries on Sophocles, Alcaeus of Mytilene and Homer, and a work on places consecrated to the gods. Photius Horapollon, a Greek grammarian, flourished in the 4th...

, whose chief contribution was the misconception that hieroglyphics were "picture writing" and that future translators should look for symbolic meaning in the pictures. The first modern study of hieroglyphics came with Piero Valeriano Bolzani

Piero Valeriano Bolzani

Piero Valeriano Bolzani , born Giampietro Valeriano Bolzani, was an Italian Renaissance humanist, favored by the Medici.-Life:...

's nonsensical Hieroglyphica (1566), but Kircher was the most famous of the "decipherers" between ancient and modern times and the most famous Egyptologist of his day. In his Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta (1643), Kircher called hieroglyphics "this language hitherto unknown in Europe, in which there are as many pictures as letters, as many riddles as sounds, in short as many mazes to be escaped from as mountains to be climbed". While some of his notions are long discredited, portions of his work have been valuable to later scholars, and Kircher helped pioneer Egyptology as a field of serious study.

Kircher's interest in Egyptology began in 1628 when he became intrigued by a collection of hieroglyphs in the library at Speyer

Speyer

Speyer is a city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located beside the river Rhine, Speyer is 25 km south of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. Founded by the Romans, it is one of Germany's oldest cities...

. He learned Coptic

Coptic language

Coptic or Coptic Egyptian is the current stage of the Egyptian language, a northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century. Egyptian began to be written using the Greek alphabet in the 1st century...

in 1633 and published the first grammar of that language in 1636, the Prodromus coptus sive aegyptiacus. Kircher then broke with Horapollon's interpretation of the language of the hieroglyphs with his Lingua aegyptiaca restituta. Kircher argued that Coptic preserved the last development of ancient Egyptian

Egyptian language

Egyptian is the oldest known indigenous language of Egypt and a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. Written records of the Egyptian language have been dated from about 3400 BC, making it one of the oldest recorded languages known. Egyptian was spoken until the late 17th century AD in the...

. For this Kircher has been considered the true "founder of Egyptology", because his work was conducted "before the discovery of the Rosetta Stone

Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is an ancient Egyptian granodiorite stele inscribed with a decree issued at Memphis in 196 BC on behalf of King Ptolemy V. The decree appears in three scripts: the upper text is Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the middle portion Demotic script, and the lowest Ancient Greek...

rendered Egyptian hieroglyphics comprehensible to scholars". He also recognised the relationship between the hieratic

Hieratic

Hieratic refers to a cursive writing system that was used in the provenance of the pharaohs in Egypt and Nubia that developed alongside the hieroglyphic system, to which it is intimately related...

and hieroglyphic scripts.

Oedipus Aegyptiacus

Oedipus Aegyptiacus is Athanasius Kircher's supreme work of Egyptology.The three full folio tomes of ornate illustrations and diagrams were published in Rome over the period 1652–54...

, Kircher argued under the impression of the Hieroglyphica that ancient Egyptian

Egyptian language

Egyptian is the oldest known indigenous language of Egypt and a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. Written records of the Egyptian language have been dated from about 3400 BC, making it one of the oldest recorded languages known. Egyptian was spoken until the late 17th century AD in the...

was the language spoken by Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve were, according to the Genesis creation narratives, the first human couple to inhabit Earth, created by YHWH, the God of the ancient Hebrews...

, that Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus is the eponymous author of the Hermetic Corpus, a sacred text belonging to the genre of divine revelation.-Origin and identity:...

was Moses

Moses

Moses was, according to the Hebrew Bible and Qur'an, a religious leader, lawgiver and prophet, to whom the authorship of the Torah is traditionally attributed...

, and that hieroglyphs were occult

Occult

The word occult comes from the Latin word occultus , referring to "knowledge of the hidden". In the medical sense it is used to refer to a structure or process that is hidden, e.g...

symbol

Symbol

A symbol is something which represents an idea, a physical entity or a process but is distinct from it. The purpose of a symbol is to communicate meaning. For example, a red octagon may be a symbol for "STOP". On a map, a picture of a tent might represent a campsite. Numerals are symbols for...

s which "cannot be translated by words, but expressed only by marks, characters and figures." This led him to translate simple hieroglyphic texts now known to read as dd Wsr ("Osiris says") as "The treachery of Typhon ends at the throne of Isis; the moisture of nature is guarded by the vigilance of Anubis".

Although his approach to deciphering the texts was based on a fundamental misconception, Kircher did pioneer serious study of hieroglyphs, and the data which he collected were later used by Champollion in his successful efforts to decode the script. Kircher himself was alive to the possibility of the hieroglyphs constituting an alphabet

Alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letters—basic written symbols or graphemes—each of which represents a phoneme in a spoken language, either as it exists now or as it was in the past. There are other systems, such as logographies, in which each character represents a word, morpheme, or semantic...

; he included in his proposed system (incorrect) derivations of the Greek alphabet

Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet is the script that has been used to write the Greek language since at least 730 BC . The alphabet in its classical and modern form consists of 24 letters ordered in sequence from alpha to omega...

from 21 hieroglyphs. However, according to Joseph MacDonnell, it was "because of Kircher's work that scientists knew what to look for when interpreting the Rosetta stone". Another scholar of ancient Egypt, Erik Iverson, concluded:

Kircher was also actively involved in the erection of obelisks in Roman squares, often adding fantastic "hieroglyphs" of his own design in the blank areas that are now puzzling to modern scholars.

Sinology

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, telling his superior in 1629 that he wished to become a missionary

Missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group sent into an area to do evangelism or ministries of service, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care and economic development. The word "mission" originates from 1598 when the Jesuits sent members abroad, derived from the Latin...

to the country. In 1667 he published a treatise whose full title was China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae and artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, and which is commonly known simply as China Illustrata, i.e. "China Illustrated". It was a work of encyclopedic breadth, combining material of unequal quality, from accurate cartography

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

to mythical elements, such as dragon

Dragon

A dragon is a legendary creature, typically with serpentine or reptilian traits, that feature in the myths of many cultures. There are two distinct cultural traditions of dragons: the European dragon, derived from European folk traditions and ultimately related to Greek and Middle Eastern...

s. The work drew heavily on the reports of Jesuits working in China, in particular Michael Boym and Martino Martini

Martino Martini

Martino Martini was an Italian Jesuit missionary, cartographer and historian, mainly working on ancient Imperial China.-Early years:Martini was born in Trento, in the Bishopric of Trent...

.

China Illustrata emphasized the Christian elements of Chinese history, both real and imagined: the book noted the early presence of Nestorian Christians (with a Latin translation of the Nestorian Stele

Nestorian Stele

The Nestorian Stele is aTang Chinese stele erected in 781 that documents 150 years of history of early Christianity in China. It is a 279-cm tall limestone block with text in both Chinese and Syriac, describing the existence of Christian communities in several cities in northern China...

of Xi'an

Xi'an

Xi'an is the capital of the Shaanxi province, and a sub-provincial city in the People's Republic of China. One of the oldest cities in China, with more than 3,100 years of history, the city was known as Chang'an before the Ming Dynasty...

provided by Boym and his Chinese collaborator, Andrew Zheng), but also claimed that the Chinese were descended from the sons of Ham

Ham, son of Noah

Ham , according to the Table of Nations in the Book of Genesis, was a son of Noah and the father of Cush, Mizraim, Phut and Canaan.- Hebrew Bible :The story of Ham is related in , King James Version:...

, that Confucius

Confucius

Confucius , literally "Master Kong", was a Chinese thinker and social philosopher of the Spring and Autumn Period....

was Hermes Trismegistus/Moses and that the Chinese character

Chinese character

Chinese characters are logograms used in the writing of Chinese and Japanese , less frequently Korean , formerly Vietnamese , or other languages...

s were abstracted hieroglyphs.

In Kircher's system, ideogram

Ideogram

An ideogram or ideograph is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept. Some ideograms are comprehensible only by familiarity with prior convention; others convey their meaning through pictorial resemblance to a physical object, and thus may also be referred to as pictograms.Examples of...

s were inferior to hieroglyphs because they referred to specific ideas rather than to mysterious complexes of ideas, while the signs of the Maya and Aztec

Aztec

The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the...

s were yet lower pictogram

Pictogram

A pictograph, also called pictogram or pictogramme is an ideogram that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. Pictographs are often used in writing and graphic systems in which the characters are to considerable extent pictorial in appearance.Pictography is a...

s which referred only to objects. Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco Knight Grand Cross is an Italian semiotician, essayist, philosopher, literary critic, and novelist, best known for his novel The Name of the Rose , an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in fiction, biblical analysis, medieval studies and literary theory...

comments that this idea reflected and supported the European attitude to the Chinese and native American civilizations;

"China was presented not as an unknown barbarian to be defeated but as a prodigal son who should return to the home of the common father". (p. 69)

Biblical studies and exegesis

In 1675, he published Arca Noë, the results of his research on the biblical Ark of NoahNoah's Ark

Noah's Ark is a vessel appearing in the Book of Genesis and the Quran . These narratives describe the construction of the ark by Noah at God's command to save himself, his family, and the world's animals from the worldwide deluge of the Great Flood.In the narrative of the ark, God sees the...

— following the Counter-Reformation

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation was the period of Catholic revival beginning with the Council of Trent and ending at the close of the Thirty Years' War, 1648 as a response to the Protestant Reformation.The Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive effort, composed of four major elements:#Ecclesiastical or...

, allegorical interpretation

Allegorical interpretation

In a biblical context, allegorical interpretation is an approach assuming that the authors of a text intended something other than what is literally expressed....

was giving way to the study of the Old Testament as literal truth among Scriptural scholars. Kircher analyzed the dimensions of the Ark; based on the number of species known to him (excluding insects and other forms thought to arise spontaneously

Spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation or Equivocal generation is an obsolete principle regarding the origin of life from inanimate matter, which held that this process was a commonplace and everyday occurrence, as distinguished from univocal generation, or reproduction from parent...

), he calculated that overcrowding would not have been a problem. He also discussed the logistics of the Ark voyage, speculating on whether extra livestock was brought to feed carnivores and what the daily schedule of feeding and caring for animals must have been.

Other cultural work

Kircher received a copy of the Voynich ManuscriptVoynich manuscript

The Voynich manuscript, described as "the world's most mysterious manuscript", is a work which dates to the early 15th century, possibly from northern Italy. It is named after the book dealer Wilfrid Voynich, who purchased it in 1912....

in 1666; sent to him by Johannes Marcus Marci in the hope of Kircher being able to decipher it. The manuscript remained in the Collegio Romano until Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

Victor Emanuel II was king of Sardinia from 1849 and, on 17 March 1861, he assumed the title King of Italy to become the first king of a united Italy since the 6th century, a title he held until his death in 1878...

annexed the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

in 1870, though scepticism as to the authenticity of the story and of the origin of the manuscript itself exists. In his Polygraphia nova (1663), Kircher proposed an artificial universal language

Universal language

Universal language may refer to a hypothetical or historical language spoken and understood by all or most of the world's population. In some circles, it is a language said to be understood by all living things, beings, and objects alike. It may be the ideal of an international auxiliary language...

.

Geology

Volcano

2. Bedrock3. Conduit 4. Base5. Sill6. Dike7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano8. Flank| 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano10. Throat11. Parasitic cone12. Lava flow13. Vent14. Crater15...

of Vesuvius, then on the brink of eruption, in order to examine its interior. He was also intrigued by the subterranean rumbling which he heard at the Strait of Messina

Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina is the narrow passage between the eastern tip of Sicily and the southern tip of Calabria in the south of Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea with the Ionian Sea, within the central Mediterranean...

. His geological and geographical investigations culminated in his Mundus Subterraneus of 1664, in which he suggested that the tide

Tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the moon and the sun and the rotation of the Earth....

s were caused by water moving to and from a subterranean ocean

Ocean

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.More than half of this area is over 3,000...

.

Kircher was also puzzled by fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

s. He understood that some were the remains of animal

Animal

Animals are a major group of multicellular, eukaryotic organisms of the kingdom Animalia or Metazoa. Their body plan eventually becomes fixed as they develop, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on in their life. Most animals are motile, meaning they can move spontaneously and...

s which had turned to stone, but ascribed others to human invention or to the spontaneous generative force of the earth

Soil

Soil is a natural body consisting of layers of mineral constituents of variable thicknesses, which differ from the parent materials in their morphological, physical, chemical, and mineralogical characteristics...

. He ascribed large bones to giant races of humans. Not all the objects which he was attempting to explain were in fact fossils, hence the diversity of explanations. He interpreted mountain ranges as the Earth's skeletal structures exposed by weathering.

Biology

In his book Arca Noë, Kircher argued that after the flood new species were transformed as they moved into different environments, for example, when a deer moved into a colder climate, it became a reindeer. Additionally, he held that many species were formed by hybrids of other species, for example, the armadillo from a combination of turtles and porcupines. He also advocated the theory of spontaneous generation. Because of such hypotheses, some historians have held that Kircher was a proto-evolutionist.Medicine

Disease

A disease is an abnormal condition affecting the body of an organism. It is often construed to be a medical condition associated with specific symptoms and signs. It may be caused by external factors, such as infectious disease, or it may be caused by internal dysfunctions, such as autoimmune...

s, as early as 1646 using a microscope

Microscope

A microscope is an instrument used to see objects that are too small for the naked eye. The science of investigating small objects using such an instrument is called microscopy...

to investigate the blood

Blood

Blood is a specialized bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells....

of plague

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

victims. In his Scrutinium Pestis of 1658, he noted the presence of "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood, and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganism

Microorganism

A microorganism or microbe is a microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters, or no cell at all...

s. The conclusion was correct, although it is likely that what he saw were in fact red

Red blood cell

Red blood cells are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system...

or white

White blood cell

White blood cells, or leukocytes , are cells of the immune system involved in defending the body against both infectious disease and foreign materials. Five different and diverse types of leukocytes exist, but they are all produced and derived from a multipotent cell in the bone marrow known as a...

blood cell

Blood cell

A blood cell, also called a hematocyte, is a cell normally found in blood. In mammals, these fall into three general categories:* red blood cells — Erythrocytes* white blood cells — Leukocytes* platelets — Thrombocytes...

s and not the plague agent, Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium. It is a facultative anaerobe that can infect humans and other animals....

. He also proposed hygienic

Hygiene

Hygiene refers to the set of practices perceived by a community to be associated with the preservation of health and healthy living. While in modern medical sciences there is a set of standards of hygiene recommended for different situations, what is considered hygienic or not can vary between...

measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine

Quarantine

Quarantine is compulsory isolation, typically to contain the spread of something considered dangerous, often but not always disease. The word comes from the Italian quarantena, meaning forty-day period....

, burning clothes worn by the infected and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germ

Microorganism

A microorganism or microbe is a microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters, or no cell at all...

s.

Technology

Magic lantern

The magic lantern or Laterna Magica is an early type of image projector developed in the 17th century.-Operation:The magic lantern has a concave mirror in front of a light source that gathers light and projects it through a slide with an image scanned onto it. The light rays cross an aperture , and...

as developed by Christiaan Huygens and others. Kircher described the construction of a "catotrophic lamp" that used reflection to project images on the wall of a darkened room. Although Kircher did not invent the device, he made improvements over previous models, and suggested methods by which exhibitors could use his device. Much of the significance of his work arises from Kircher's rational approach towards the demystification of projected images. Previously such images had been used in Europe to mimic supernatural appearances (Kircher himself cites the use of displayed images by the rabbis in the court of King Solomon). Kircher stressed that exhibitors should take great care to inform spectators that such images were purely naturalistic, and not magical in origin.

Kircher also constructed a magnetic

Magnetism

Magnetism is a property of materials that respond at an atomic or subatomic level to an applied magnetic field. Ferromagnetism is the strongest and most familiar type of magnetism. It is responsible for the behavior of permanent magnets, which produce their own persistent magnetic fields, as well...

clock, the mechanism of which he explained in his Magnes (1641). The device had originally been invented by another Jesuit, Fr. Linus of Liege, and was described by an acquaintance of Line's in 1634. Kircher's patron Peiresc had claimed that the clock's motion supported the Copernican

Copernican

Copernican means of or pertaining to the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus* For the Copernican system of astronomy, see heliocentrism* For the philosophical principle, see Copernican principle* For the lunar geological period, see Copernician...

cosmological model, the argument being that the magnetic sphere in the clock was caused to rotate by the magnetic force of the sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

. Kircher's model disproved the hypothesis, showing that the motion could be produced by a water clock

Water clock

A water clock or clepsydra is any timepiece in which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into or out from a vessel where the amount is then measured.Water clocks, along with sundials, are likely to be the oldest time-measuring instruments, with the only exceptions...

in the base of the device. Although Kircher wrote against the Copernican

Copernican

Copernican means of or pertaining to the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus* For the Copernican system of astronomy, see heliocentrism* For the philosophical principle, see Copernican principle* For the lunar geological period, see Copernician...

model in his Magnes, supporting instead that of Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe , born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, was a Danish nobleman known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical and planetary observations...

, his later Itinerarium extaticum (1656, revised 1671), presented several systems — including the Copernican — as distinct possibilities. The clock has been reconstructed by Caroline Bouguereau in collaboration with Michael John Gorman and is on display at the Green Library at Stanford University..

The Musurgia Universalis (1650) sets out Kircher's views on music

Music

Music is an art form whose medium is sound and silence. Its common elements are pitch , rhythm , dynamics, and the sonic qualities of timbre and texture...

: he believed that the harmony

Harmony

In music, harmony is the use of simultaneous pitches , or chords. The study of harmony involves chords and their construction and chord progressions and the principles of connection that govern them. Harmony is often said to refer to the "vertical" aspect of music, as distinguished from melodic...

of music reflected the proportions of the universe

Universe

The Universe is commonly defined as the totality of everything that exists, including all matter and energy, the planets, stars, galaxies, and the contents of intergalactic space. Definitions and usage vary and similar terms include the cosmos, the world and nature...

. The book includes plans for constructing water-powered automatic organs, notations

Musical notation

Music notation or musical notation is any system that represents aurally perceived music, through the use of written symbols.-History:...

of birdsong

Birdsong

Birdsong may refer to:* Bird vocalization, the sounds of birds* Birdsong , a 1993 novel by Sebastian Faulks* Birdsong, Arkansas, USA* Birdsong , a channel on the UK Digital One digital radio multiplex...

and diagrams of musical instrument

Musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted for the purpose of making musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can serve as a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. The history of musical instruments dates back to the...

s. One illustration shows the differences between the ear

Ear

The ear is the organ that detects sound. It not only receives sound, but also aids in balance and body position. The ear is part of the auditory system....

s of humans and other animals. In Phonurgia Nova (1673) Kircher considered the possibilities of transmitting music to remote places.

Other machines designed by Kircher include an aeolian harp

Aeolian harp

An aeolian harp is a musical instrument that is "played" by the wind. It is named for Aeolus, the ancient Greek god of the wind. The traditional aeolian harp is essentially a wooden box including a sounding board, with strings stretched lengthwise across two bridges...

, automaton

Automaton

An automaton is a self-operating machine. The word is sometimes used to describe a robot, more specifically an autonomous robot. An alternative spelling, now obsolete, is automation.-Etymology:...

s such as a statue which spoke and listened via a speaking tube

Speaking tube

A speaking tube or voicepipe is a device based on two cones connected by an air pipe through which speech can be transmitted over an extended distance. While its most common use was in intra-ship communications, the principle was also used in fine homes and offices of the 19th century, as well as...

, a perpetual motion machine, and a Katzenklavier

Katzenklavier

A cat organ or cat piano is a musical instrument which consists of a line of cats fixed in place with their tails stretched out underneath a keyboard so that cats cry out in pain when a key is pressed...

("cat piano"). This last of these would have driven spikes into the tails of cats, which would yowl to specified pitches

Pitch (music)

Pitch is an auditory perceptual property that allows the ordering of sounds on a frequency-related scale.Pitches are compared as "higher" and "lower" in the sense associated with musical melodies,...

, although Kircher is not known to have actually constructed the instrument.

Combinatorics

Although Kircher's work was not mathematically based, he did develop various systems for generating and counting all combinations of a finite collection of objects (i.e. a finite setSet theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematics that studies sets, which are collections of objects. Although any type of object can be collected into a set, set theory is applied most often to objects that are relevant to mathematics...

). His methods and diagrams are discussed in Ars Magna Sciendi, sive Combinatoria (sic).

Legacy

Scholarly influence

For most of his professional life, Kircher was one of the scientific stars of the world: according to historian Paula Findlen, he was "the first scholar with a global reputation". His importance was twofold: to the results of his own experimentExperiment

An experiment is a methodical procedure carried out with the goal of verifying, falsifying, or establishing the validity of a hypothesis. Experiments vary greatly in their goal and scale, but always rely on repeatable procedure and logical analysis of the results...

s and research he added information gleaned from his correspondence with over 760 scientists, physicians and above all his fellow Jesuits in all parts of the globe. The Encyclopædia Britannica

Encyclopædia Britannica

The Encyclopædia Britannica , published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia that is available in print, as a DVD, and on the Internet. It is written and continuously updated by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 expert...

calls him a "one-man intellectual clearing house". His works, illustrated to his orders, were extremely popular, and he was the first scientist to be able to support himself through the sale of his books. Towards the end of his life his stock fell, as the rationalist

Rationalism

In epistemology and in its modern sense, rationalism is "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification" . In more technical terms, it is a method or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive"...

Cartesian

René Descartes

René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day...

approach began to dominate (Descartes himself described Kircher as "more quacksalver than savant").

Cultural legacy

Kircher was largely neglected until the late 20th century. One writer attributes his rediscovery to the similarities between his eclectic approach and postmodernismPostmodernism

Postmodernism is a philosophical movement evolved in reaction to modernism, the tendency in contemporary culture to accept only objective truth and to be inherently suspicious towards a global cultural narrative or meta-narrative. Postmodernist thought is an intentional departure from the...

:

He added that "Kircher's postmodern qualities include his subversiveness, his celebrity, his technomania and his bizarre eclecticism

Eclecticism

Eclecticism is a conceptual approach that does not hold rigidly to a single paradigm or set of assumptions, but instead draws upon multiple theories, styles, or ideas to gain complementary insights into a subject, or applies different theories in particular cases.It can sometimes seem inelegant or...

". In Robert Graham Irwin

Robert Graham Irwin

Robert Graham Irwin is a British historian, novelist, and writer on Arabic literature.He read modern history at the University of Oxford, and did graduate research at SOAS. From 1972 he was a lecturer in Medieval History at the University of St. Andrews. He gave up academic life in 1977 in order...

's For Lust of Knowing

For Lust of Knowing