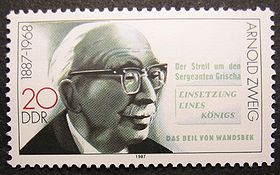

Arnold Zweig

Encyclopedia

He is best known for his World War I tetralogy.

Life and work

Zweig was born in Glogau, Silesia (today Głogów, Poland) son of a Jewish saddler. After attending a gymnasiumGymnasium (school)

A gymnasium is a type of school providing secondary education in some parts of Europe, comparable to English grammar schools or sixth form colleges and U.S. college preparatory high schools. The word γυμνάσιον was used in Ancient Greece, meaning a locality for both physical and intellectual...

in Kattowitz (Katowice

Katowice

Katowice is a city in Silesia in southern Poland, on the Kłodnica and Rawa rivers . Katowice is located in the Silesian Highlands, about north of the Silesian Beskids and about southeast of the Sudetes Mountains.It is the central district of the Upper Silesian Metropolis, with a population of 2...

), he made extensive studies in history, philosophy and literature at several universities - Breslau (Wrocław), Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, Berlin, Göttingen

Göttingen

Göttingen is a university town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Göttingen. The Leine river runs through the town. In 2006 the population was 129,686.-General information:...

, Rostock

Rostock

Rostock -Early history:In the 11th century Polabian Slavs founded a settlement at the Warnow river called Roztoc ; the name Rostock is derived from that designation. The Danish king Valdemar I set the town aflame in 1161.Afterwards the place was settled by German traders...

and Tübingen

Tübingen

Tübingen is a traditional university town in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, on a ridge between the Neckar and Ammer rivers.-Geography:...

. He was especially influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

's philosophy. His first literary works Novellen um Claudia (1913) and Ritualmord in Ungarn gained him wider recognition.

Zweig volunteered for the German army in World War I and saw action as a private in France, Hungary and Serbia. He was stationed in the Western Front at the time when Judenzählung (the Jewish census) was administered in the German army. Shaken by the experience, he wrote in his letter dated February 15, 1917 to Martin Buber

Martin Buber

Martin Buber was an Austrian-born Jewish philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of religious existentialism centered on the distinction between the I-Thou relationship and the I-It relationship....

: "The Judenzählung was a reflection of unheard sadness for Germany's sin and our agony... If there was no antisemitism in the army, the unbearable call to duty would be almost easy." He began to revise his views on the war and to realize that it pitted Jews against Jews.

Later he described his experiences in the short story Judenzählung vor Verdun. The war changed Zweig from a Prussian patriot to an eager pacifist.

By the end of the war he was assigned to the Press department of the German Army Headquarters in Kaunas and there he was first introduced to the East European Jewish organizations.

In a quite literal effort to put a face to the hated 'Ostjude' (Eastern European Jew), due to their Orthodox, economically depressed, "unenlightened", "un-German" ways, Zweig published with the artist Hermann Struck

Hermann Struck

Hermann Struck was a German Jewish artist known for his etchings.Hermann Struck was born in Berlin. He studied at the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts. In 1904, he joined the modern art movement known as the Berlin Secession.In 1900, Struck met Jozef Israëls, a Dutch artist, who became his mentor...

Das ostjüdische Antlitz (The Face of East European Jewry) in 1920. This was a blatant effort to at least gain sympathy among German Jews for the plight of their eastern European brethren. With the help of many simple sketches of faces, Zweig supplied interpretations and meaning behind them.

After World War I he was an active socialistic Zionist in Germany. After Hitler's attempted coup in 1923 Zweig went to Berlin and worked as an editor of a newspaper, the Jüdische Rundschau.

In the 1920s, Zweig became attracted to the psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud , born Sigismund Schlomo Freud , was an Austrian neurologist who founded the discipline of psychoanalysis...

and underwent Freudian therapy himself. In March 1927 Zweig wrote to Freud asking permission to dedicate his new book to Freud. In the letter Zweig told Freud: "I personally owe to your psychological therapy the restoration of my whole personality, the discovery that I was suffering from a neurosis and finally the curing of this neurosis by your method of treatment."

Freud returned this ardent letter with a warm letter of his own, and the Freud-Zweig correspondence continued for a dozen years - momentous years in Germany's history. This correspondence is extensive and interesting enough to have been published in book form.

In 1927 Zweig published the anti-war novel The Case of Sergeant Grischa

The Case of Sergeant Grischa

The Case of Sergeant Grischa is a war novel by the German writer Arnold Zweig. Its original German title is Der Streit um den Sergeanten Grischa. It is part of Zweig's hexalogy Der große Krieg der weißen Männer...

, which made him an international literary figure. From 1929 he was a contributing journalist of anti-Nazi newspaper Die Weltbühne

Die Weltbühne

Die Weltbühne was a German weekly magazine focused on politics, art, and business. The Weltbühne was founded in Berlin on 7 September 1905 by Siegfried Jacobsohn and was originally created strictly as a theater magazine under the title Die Schaubühne. It was renamed Die Weltbühne on 4 April 1918...

(World Stage). That year, Zweig would attend one of Hitler's speeches. He told his wife that the man was a Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE was an English comic actor, film director and composer best known for his work during the silent film era. He became the most famous film star in the world before the end of World War I...

without the talent. Zweig would later witness the burning of his books by the Nazis. He remarked that the crowd "would have stared as happily into the flames if live humans were burning." He made the decision to leave Germany that night.

When the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, Zweig was one of many Jews who immediately went into voluntary exile. Zweig went first to Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, then Switzerland and France. After spending some time with Thomas Mann

Thomas Mann

Thomas Mann was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and 1929 Nobel Prize laureate, known for his series of highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novellas, noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual...

, Lion Feuchtwanger

Lion Feuchtwanger

Lion Feuchtwanger was a German-Jewish novelist and playwright. A prominent figure in the literary world of Weimar Germany, he influenced contemporaries including playwright Bertolt Brecht....

, Anna Seghers

Anna Seghers

Anna Seghers was a German writer famous for depicting the moral experience of the Second World War.- Life :...

and Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht was a German poet, playwright, and theatre director.An influential theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht made equally significant contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter particularly through the seismic impact of the tours undertaken by the...

in France he set out for Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

.

In Haifa

Haifa

Haifa is the largest city in northern Israel, and the third-largest city in the country, with a population of over 268,000. Another 300,000 people live in towns directly adjacent to the city including the cities of the Krayot, as well as, Tirat Carmel, Daliyat al-Karmel and Nesher...

, Palestine, he published a German newspaper Orient. During the years spent in Palestine he became disillusioned with Zionism and turned to socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

.

His 1947 book The Axe of Wandsbek concerned the 'Altona

Altona, Hamburg

Altona is the westernmost urban borough of the German city state of Hamburg, on the right bank of the Elbe river. From 1640 to 1864 Altona was under the administration of the Danish monarchy. Altona was an independent city until 1937...

Bloody Sunday' ('Altonaer Blutsonntag') riot, an SA

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

march on 17 July 1932 that turned violent and led to 18 people being shot dead, with four Communists including Bruno Tesch

Bruno Tesch (antifascist)

Bruno Guido Camillo Tesch was a German antifascist and member of the Young Communist League of Germany. Aged 20, he was convicted of murder and executed in connection with the Altona Bloody Sunday riot, an SA march on 17 July 1932 that turned violent and led to 18 people being shot and killed...

subsequently being beheaded for their alleged involvement.

In 1948, after a formal invitation from the East German government, Zweig decided to return to the Soviet Zone (later called the GDR). In East Germany he was in many ways involved in the communist system. He was a member of parliament, delegate to the World Peace Council

World Peace Council

The World Peace Council is an international organization that advocates universal disarmament, sovereignty and independence and peaceful co-existence, and campaigns against imperialism, weapons of mass destruction and all forms of discrimination...

Congresses and the cultural advisory board of the communist party. He was President of the German Academy of the Arts from 1950-53.

He was rewarded with many prizes and medals by the regime. The USSR awarded him the Lenin Peace Prize

Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize was the Soviet Union's equivalent to the Nobel Peace Prize, named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a panel appointed by the Soviet government, to notable individuals whom the panel indicated had "strengthened peace among peoples"...

(1958) for his anti-war novels.

After 1962, due to poor health, Zweig virtually withdrew from the political and artistic fields. Arnold Zweig died in East Berlin

East Berlin

East Berlin was the name given to the eastern part of Berlin between 1949 and 1990. It consisted of the Soviet sector of Berlin that was established in 1945. The American, British and French sectors became West Berlin, a part strongly associated with West Germany but a free city...

on 26 November 1968.

See also

- ExilliteraturExilliteraturGerman Exilliteratur is the name for a category of books in the German language written by writers of anti-nazi attitude who fled from Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1945...