Anaximander

Encyclopedia

Anaximander əˌnæksɨˈmændər (Greek

: , Anaximandros; c. 610 – c. 546 BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek

philosopher who lived in Miletus

, a city of Ionia

; Milet in modern Turkey

. He belonged to the Milesian school

and learned the teachings of his master Thales

. He succeeded Thales and became the second master of that school where he counted Anaximenes

and arguably, Pythagoras

amongst his pupils.

Little of his life and work is known today. According to available historical documents, he is the first philosopher known to have written down his studies, although only one fragment of his work remains. Fragmentary testimonies found in documents after his death provide a portrait of the man.

Anaximander was one of the earliest Greek thinkers at the start of the Axial Age

, the period from approximately 700 BC to 200 BC, during which similarly revolutionary thinking appeared in China, India, Iran, the Near East, and Ancient Greece. He was an early proponent of science

and tried to observe and explain different aspects of the universe, with a particular interest in its origins, claiming that nature is ruled by laws, just like human societies, and anything that disturbs the balance of nature does not last long. Like many thinkers of his time, Anaximander's contributions to philosophy

relate to many disciplines. In astronomy

, he tried to describe the mechanics of celestial bodies in relation to the Earth. In physics, his postulation that the indefinite (or apeiron

) was the source of all things led Greek philosophy to a new level of conceptual abstraction. His knowledge of geometry

allowed him to introduce the gnomon

in Greece. He created a map of the world that contributed greatly to the advancement of geography

. He was also involved in the politics

of Miletus and was sent as a leader to one of its colonies.

Anaximander claimed that an 'indefinite' (apeiron) principle gives rise to all natural phenomena. Carl Sagan claims that he conducted the earliest recorded scientific experiment.

during the third year of the 42nd Olympiad

(610 BC). According to Apollodorus

, Greek grammarian of the 2nd century BC, he was sixty-four years old during the second year of the 58th Olympiad (547-546 BC), and died shortly afterwards.

Establishing a timeline of his work is now impossible, since no document provides chronological references. Themistius

, a 4th century Byzantine

rhethorician

, mentions that he was the "first of the known Greeks to publish a written document on nature." Therefore his texts would be amongst the earliest written in prose

, at least in the Western world. By the time of Plato

, his philosophy was almost forgotten, and Aristotle

, his successor Theophrastus

and a few doxographers

provide us with the little information that remains. However, we know from Aristotle that Thales, also from Miletus, precedes Anaximander. It is debatable whether Thales actually was the teacher of Anaximander, but there is no doubt that Anaximander was influenced by Thales' theory that everything is derived from water. One thing that is not debatable is that even the ancient Greeks considered Anaximander to be from the Monist school which began in Miletus with Thales followed by Anaximander and finished with Anaximenes

. 3rd century Roman

rhetorician Aelian

depicts him as leader of the Milesian colony to Apollonia

on the Black Sea

coast, and hence some have inferred that he was a prominent citizen. Indeed, Various History (III, 17) explains that philosophers sometimes also dealt with political matters. It is very likely that leaders of Miletus sent him there as a legislator to create a constitution or simply to maintain the colony’s allegiance.

tradition, and by some ideas of Thales

– the father of philosophy – as well as by observations made by older civilizations in the East (especially by the Babylonian astrologists). All these were elaborated rationally. In his desire to find some universal principle, he assumed like traditional religion the existence of a cosmic order and in elaborating his ideas on this he used the old mythical language which ascribed divine control to various spheres of reality. This was a common practice for the Greek philosophers in a society which saw gods everywhere, therefore they could fit their ideas into a tolerably elastic system.

Some scholars saw a gap between the existing mythical and the new rational

way of thought which is the main characteristic of the archaic period (8th to 6th century BC) in the Greek city states. Because of this, they didn't hesitate to speak for a 'Greek miracle'. But if we follow carefully the course of Anaximander's ideas, we will notice that there was not such an abrupt break as initially appears. The basic elements of nature (water

, air

, fire

, earth

) which the first Greek philosophers believed that constituted the universe represent in fact the primordial

forces of previous thought. Their collision produced what the mythical tradition had called cosmic harmony. In the old cosmogonies – Hesiod

(8th-7th century BC) and Pherecydes

(6th century BC) – Zeus

establishes his order in the world by destroying the powers which were threatening this harmony, (the Titans). Anaximander claimed that the cosmic order is not monarchic but geometric and this causes the equilibrium of the earth which is lying in the centre of the universe. This is the projection on nature of a new political order and a new space organized around a centre which is the static point of the system in the society as in nature. In this space there is isonomy (equal rights) and all the forces are symmetrical and transferrable. The decisions are now taken by the assembly of demos in the agora

which is lying in the middle of the city.

The same rational way of thought led him to introduce the abstract apeiron

(indefinite, infinite, boundless, unlimited) as an origin of the universe, a concept that is probably influenced by the original Chaos

(gaping void, abyss, formless state) of the mythical Greek

cosmogony

from which everything else appeared. It also takes notice of the mutual changes between the four elements. Origin, then, must be something else unlimited in its source, that could create without experiencing decay, so that genesis would never stop.

Hippolytus of Rome (I, 5), and the later 6th century Byzantine philosopher Simplicius of Cilicia

, attribute to Anaximander the earliest use of the word apeíron ( infinite or limitless) to designate the original principle. He was the first philosopher to employ, in a philosophical context, the term arkhế

, which until then had meant beginning or origin. For him, it became no longer a mere point in time, but a source that could perpetually give birth to whatever will be. The indefiniteness is spatial in early usages as in Homer

(indefinite sea) and as in Xenophanes

(6th century BC) who said that the earth went down indefinitely (to apeiron) i.e. beyond the imagination or concept of men.

Aristotle writes (Metaphysics

, I III 3-4) that the Pre-Socratics

were searching for the element that constitutes all things. While each pre-Socratic philosopher gave a different answer as to the identity of this element (water

for Thales and air

for Anaximenes), Anaximander understood the beginning or first principle to be an endless, unlimited primordial mass (apeiron), subject to neither old age nor decay, that perpetually yielded fresh materials from which everything we perceive is derived. He proposed the theory of the apeiron in direct response to the earlier theory of his teacher, Thales, who had claimed that the primary substance was water. The notion of temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious concept of immortality and Anaximander's description was in terms appropriate to this conception. This arche is called "eternal and ageless". (Hippolitus I,6,I;DK B2)

For Anaximander, the principle

of things, the constituent of all substances, is nothing determined and not an element such as water in Thales' view. Neither is it something halfway between air and water, or between air and fire, thicker than air and fire, or more subtle than water and earth. Anaximander argues that water cannot embrace all of the opposites found in nature — for example, water can only be wet, never dry — and therefore cannot be the one primary substance; nor could any of the other candidates. He postulated the apeiron as a substance that, although not directly perceptible to us, could explain the opposites he saw around him.

Anaximander explains how the four elements

of ancient physics (air

, earth

, water

and fire

) are formed, and how Earth and terrestrial beings are formed through their interactions. Unlike other Pre-Socratics, he never defines this principle precisely, and it has generally been understood (e.g., by Aristotle and by Saint Augustine

) as a sort of primal chaos

. According to him, the Universe originates in the separation of opposites in the primordial matter. It embraces the opposites of hot and cold, wet and dry, and directs the movement of things; an entire host of shapes and differences then grow that are found in "all the worlds" (for he believed there were many).

Anaximander maintains that all dying things are returning to the element from which they came (apeiron). The one surviving fragment of Anaximander's writing deals with this matter. Simplicius transmitted it as a quotation, which describes the balanced and mutual changes of the elements:

Simplicius mentions that Anaximander said all these "in poetic terms", meaning that he used the old mythical language. The goddess Justice (Dike

) keeps the cosmic order.

This concept of returning to the element of origin was often revisited afterwards, notably by Aristotle, and by the Greek tragedian

Euripides

: "what comes from earth must return to earth." Friedrich Nietzsche

, in his Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks

, stated that Anaximander viewed "...all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance."

Anaximander's bold use of non-mythological

Anaximander's bold use of non-mythological

explanatory hypotheses considerably distinguishes him from previous cosmology writers such as Hesiod

. It confirms that pre-Socratic philosophers were making an early effort to demythify physical processes. His major contribution to history was writing the oldest prose document about the Universe

and the origins of life

; for this he is often called the "Father of Cosmology

" and founder of astronomy. However, pseudo-Plutarch

states that he still viewed celestial bodies as deities.

Anaximander was the first to conceive a mechanical

model of the world

. In his model, the Earth

floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. It remains "in the same place because of its indifference", a point of view that Aristotle considered ingenious, but false, in On the Heavens

. Its curious shape is that of a cylinder

with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

Such a model allowed the concept that celestial bodies

could pass under it. It goes further than Thales’ claim of a world floating on water, for which Thales faced the problem of explaining what would contain this ocean, while Anaximander solved it by introducing his concept of infinite (apeiron).

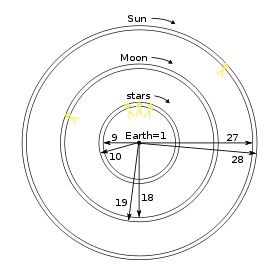

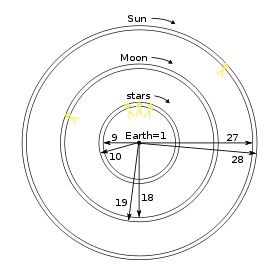

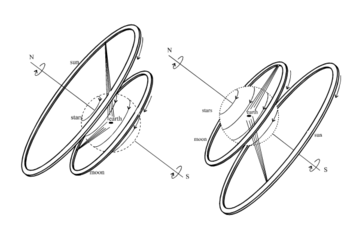

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold

, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun

was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the occlusion

of that hole. The diameter of the solar wheel was twenty-seven times that of the Earth (or twenty-eight, depending on the sources) and the lunar

wheel, whose fire was less intense, eighteen (or nineteen) times. Its hole could change shape, thus explaining lunar phase

s. The star

s and the planet

s, located closer, followed the same model.

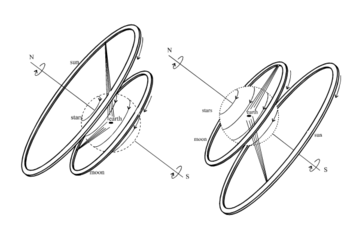

Anaximander was the first astronomer to consider the Sun as a huge mass, and consequently, to realize how far from Earth it might be, and the first to present a system where the celestial bodies turned at different distances. Furthermore, according to Diogenes Laertius (II, 2), he built a celestial sphere

. This invention undoubtedly made him the first to realize the obliquity

of the Zodiac

as the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder

reports in Natural History (II, 8). It is a little early to use the term ecliptic

, but his knowledge and work on astronomy confirm that he must have observed the inclination of the celestial sphere in relation to the plane of the Earth to explain the seasons. The doxographer

and theologian Aetius attributes to Pythagoras the exact measurement of the obliquity.

Leucippus

and Democritus

, and later philosopher Epicurus

. These thinkers supposed that worlds appeared and disappeared for a while, and that some were born when others perished. They claimed that this movement was eternal, "for without movement, there can be no generation, no destruction".

In addition to Simplicius, Hippolytus reports Anaximander's claim that from the infinite comes the principle of beings, which themselves come from the heavens and the worlds (several doxographers use the plural when this philosopher is referring to the worlds within, which are often infinite in quantity). Cicero

writes that he attributes different gods to the countless worlds.

This theory places Anaximander close to the Atomists and the Epicureans

who, more than a century later, also claimed that an infinity of worlds appeared and disappeared. In the timeline of the Greek history of thought, some thinkers conceptualized a single world (Plato, Aristotle, Anaxagoras

and Archelaus

), while others instead speculated on the existence of a series of worlds, continuous or non-continuous (Anaximenes, Heraclitus, Empedocles

and Diogenes

).

and lightning

, to the intervention of elements, rather than to divine causes. In his system, thunder results from the shock of clouds hitting each other; the loudness of the sound is proportionate with that of the shock. Thunder without lightning is the result of the wind being too weak to emit any flame, but strong enough to produce a sound. A flash of lightning without thunder is a jolt of the air that disperses and falls, allowing a less active fire to break free. Thunderbolts are the result of a thicker and more violent air flow.

He saw the sea as a remnant of the mass of humidity that once surrounded Earth. A part of that mass evaporated under the sun's action, thus causing the winds and even the rotation of the celestial bodies, which he believed were attracted to places where water is more abundant. He explained rain as a product of the humidity pumped up from Earth by the sun. For him, the Earth was slowly drying up and water only remained in the deepest regions, which someday would go dry as well. According to Aristotle's Meteorology

(II, 3), Democritus also shared this opinion.

of animal life. Taking into account the existence of fossils, he claimed that animals sprang out of the sea long ago. The first animals were born trapped in a spiny bark, but as they got older, the bark would dry up and break. As the early humidity evaporated, dry land emerged and, in time, humankind had to adapt. The 3rd century Roman writer Censorinus

reports:

Anaximander put forward the idea that humans had to spend part of this transition inside the mouths of big fish to protect themselves from the Earth's climate until they could come out in open air and lose their scales. He thought that, considering humans' extended infancy, we could not have survived in the primeval world in the same manner we do presently.

Even though he had no theory of natural selection

, some people consider him as evolution's most ancient proponent. The theory of an aquatic descent of man was re-conceived centuries later as the aquatic ape hypothesis

. These pre-Darwinian concepts may seem strange, considering modern knowledge and scientific methods, because they present complete explanations of the universe while using bold and hard-to-demonstrate hypotheses. However, they illustrate the beginning of a phenomenon sometimes called the "Greek miracle": men try to explain the nature of the world, not with the aid of myths or religion, but with material principles. This is the very principle of scientific thought, which was later advanced further by improved research methods.

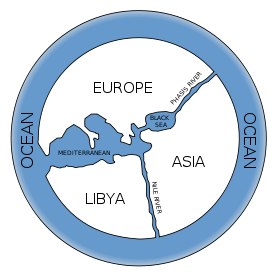

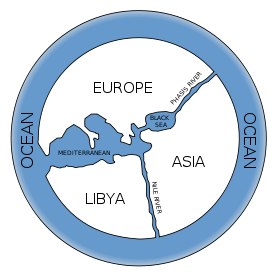

Both Strabo

Both Strabo

and Agathemerus

(later Greek geographers) claim that, according to the geographer Eratosthenes

, Anaximander was the first to publish a map of the world. The map probably inspired the Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus to draw a more accurate version. Strabo viewed both as the first geographers after Homer

.

Maps were produced in ancient times, also notably in Egypt

, Lydia

, the Middle East

, and Babylon

. Only some small examples survived until today. The unique example of a world map comes from late Babylonian tablet BM 92687 later than 9th century BCE but is based probably on a much older map. These maps indicated directions, roads, towns, borders, and geological features. Anaximander's innovation was to represent the entire inhabited land known to the ancient Greeks.

Such an accomplishment is more significant than it at first appears. Anaximander most likely drew this map for three reasons. First, it could be used to improve navigation and trade between Miletus

's colonies and other colonies around the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea. Second, Thales

would probably have found it easier to convince the Ionian city-states

to join in a federation in order to push the Median

threat away if he possessed such a tool. Finally, the philosophical idea of a global representation of the world simply for the sake of knowledge was reason enough to design one.

Surely aware of the sea's convexity, he may have designed his map on a slightly rounded metal surface. The centre or “navel” of the world ( omphalós gẽs) could have been Delphi

, but is more likely in Anaximander's time to have been located near Miletus. The Aegean Sea

was near the map's centre and enclosed by three continents, themselves located in the middle of the ocean and isolated like islands by sea and rivers. Europe

was bordered on the south by the Mediterranean Sea

and was separated from Asia

by the Black Sea, the Lake Maeotis

, and, further east, either by the Phasis River

(now called the Rioni) or the Tanais

. The Nile

flowed south into the ocean, separating Libya

(which was the name for the part of the then-known Africa

n continent) from Asia.

relates that Anaximander explained some basic notions of geometry. It also mentions his interest in the measurement of time and associates him with the introduction in Greece

of the gnomon. In Lacedaemon, he participated in the construction, or at least in the adjustment, of sundial

s to indicate solstice

s and equinox

es. Indeed, a gnomon required adjustments from a place to another because of the difference in latitude.

In his time, the gnomon was simply a vertical pillar or rod mounted on a horizontal plane. The position of its shadow on the plane indicated the time of day. As it moves through its apparent course, the sun draws a curve with the tip of the projected shadow, which is shortest at noon, when pointing due south. The variation in the tip’s position at noon indicates the solar time and the seasons; the shadow is longest on the winter solstice and shortest on the summer solstice.

However, the invention of the gnomon itself cannot be attributed to Anaximander because its use, as well as the division of days into twelve parts, came from the Babylonia

ns. It is they, according to Herodotus

' Histories

(II, 109), who gave the Greeks the art of time measurement. It is likely that he was not the first to determine the solstices, because no calculation is necessary. On the other hand, equinoxes do not correspond to the middle point between the positions during solstices, as the Babylonians thought. As the Suda seems to suggest, it is very likely that with his knowledge of geometry, he became the first Greek to accurately determine the equinoxes.

(I, 50, 112), Cicero states that Anaximander convinced the inhabitants of Lacedaemon to abandon their city and spend the night in the country with their weapons because an earthquake was near. The city collapsed when the top of the Taygetus

split like the stern of a ship. Pliny the Elder also mentions this anecdote (II, 81), suggesting that it came from an "admirable inspiration", as opposed to Cicero, who did not associate the prediction with divination.

in the History of Western Philosophy

interprets Anaximander's theories as an assertion of the necessity of an appropriate balance between earth, fire, and water, all of which may be independently seeking to aggrandize their proportions relative to the others. Anaximander seems to express his belief that a natural order ensures balance between these elements, that where there was fire, ashes (earth) now exist. His Greek peers echoed this sentiment with their belief in natural boundaries beyond which not even their gods could operate.

Friedrich Nietzsche

, in Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks

, claimed that Anaximander was a pessimist who asserted that the primal being of the world was a state of indefiniteness. In accordance with this, anything definite has to eventually pass back into indefiniteness. In other words, Anaximander viewed "...all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance". (Ibid., § 4) The world of individual objects, in this way of thinking, has no worth and should perish.

Martin Heidegger

lectured extensively on Anaximander, and delivered a lecture entitled "Anaximander's Saying" which was subsequently included in Off the Beaten Track. The lecture examines the ontological difference and the oblivion of Being or Dasein

in the context of the Anaximander fragment. Heidegger's lecture is, in turn, an important influence on the French philosopher Jacques Derrida

.

Attribution

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

: , Anaximandros; c. 610 – c. 546 BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

philosopher who lived in Miletus

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

, a city of Ionia

Ionia

Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements...

; Milet in modern Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

. He belonged to the Milesian school

Milesian school

The Milesian school was a school of thought founded in the 6th century BC. The ideas associated with it are exemplified by three philosophers from the Ionian town of Miletus, on the Aegean coast of Anatolia: Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes...

and learned the teachings of his master Thales

Thales

Thales of Miletus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor, and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition...

. He succeeded Thales and became the second master of that school where he counted Anaximenes

Anaximenes of Miletus

Anaximenes of Miletus was an Archaic Greek Pre-Socratic philosopher active in the latter half of the 6th century BC. One of the three Milesian philosophers, he is identified as a younger friend or student of Anaximander. Anaximenes, like others in his school of thought, practiced material monism...

and arguably, Pythagoras

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos was an Ionian Greek philosopher, mathematician, and founder of the religious movement called Pythagoreanism. Most of the information about Pythagoras was written down centuries after he lived, so very little reliable information is known about him...

amongst his pupils.

Little of his life and work is known today. According to available historical documents, he is the first philosopher known to have written down his studies, although only one fragment of his work remains. Fragmentary testimonies found in documents after his death provide a portrait of the man.

Anaximander was one of the earliest Greek thinkers at the start of the Axial Age

Axial Age

German philosopher Karl Jaspers coined the term the axial age or axial period to describe the period from 800 to 200 BC, during which, according to Jaspers, similar revolutionary thinking appeared in India, China and the Occident...

, the period from approximately 700 BC to 200 BC, during which similarly revolutionary thinking appeared in China, India, Iran, the Near East, and Ancient Greece. He was an early proponent of science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

and tried to observe and explain different aspects of the universe, with a particular interest in its origins, claiming that nature is ruled by laws, just like human societies, and anything that disturbs the balance of nature does not last long. Like many thinkers of his time, Anaximander's contributions to philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

relate to many disciplines. In astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

, he tried to describe the mechanics of celestial bodies in relation to the Earth. In physics, his postulation that the indefinite (or apeiron

Apeiron (cosmology)

Apeiron is a Greek word meaning unlimited, infinite or indefinite from ἀ- a-, "without" and πεῖραρ peirar, "end, limit", the Ionic Greek form of πέρας peras, "end, limit, boundary".-Apeiron as an origin:...

) was the source of all things led Greek philosophy to a new level of conceptual abstraction. His knowledge of geometry

Geometry

Geometry arose as the field of knowledge dealing with spatial relationships. Geometry was one of the two fields of pre-modern mathematics, the other being the study of numbers ....

allowed him to introduce the gnomon

Gnomon

The gnomon is the part of a sundial that casts the shadow. Gnomon is an ancient Greek word meaning "indicator", "one who discerns," or "that which reveals."It has come to be used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields....

in Greece. He created a map of the world that contributed greatly to the advancement of geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

. He was also involved in the politics

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

of Miletus and was sent as a leader to one of its colonies.

Anaximander claimed that an 'indefinite' (apeiron) principle gives rise to all natural phenomena. Carl Sagan claims that he conducted the earliest recorded scientific experiment.

Biography

Anaximander, son of Praxiades, was born in MiletusMiletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

during the third year of the 42nd Olympiad

Olympiad

An Olympiad is a period of four years, associated with the Olympic Games of Classical Greece. In the Hellenistic period, beginning with Ephorus, Olympiads were used as calendar epoch....

(610 BC). According to Apollodorus

Apollodorus

Apollodorus of Athens son of Asclepiades, was a Greek scholar and grammarian. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon, Panaetius the Stoic, and the grammarian Aristarchus of Samothrace...

, Greek grammarian of the 2nd century BC, he was sixty-four years old during the second year of the 58th Olympiad (547-546 BC), and died shortly afterwards.

Establishing a timeline of his work is now impossible, since no document provides chronological references. Themistius

Themistius

Themistius , named , was a statesman, rhetorician, and philosopher. He flourished in the reigns of Constantius II, Julian, Jovian, Valens, Gratian, and Theodosius I; and he enjoyed the favour of all those emperors, notwithstanding their many differences, and the fact that he himself was not a...

, a 4th century Byzantine

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

rhethorician

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

, mentions that he was the "first of the known Greeks to publish a written document on nature." Therefore his texts would be amongst the earliest written in prose

Prose

Prose is the most typical form of written language, applying ordinary grammatical structure and natural flow of speech rather than rhythmic structure...

, at least in the Western world. By the time of Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, his philosophy was almost forgotten, and Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, his successor Theophrastus

Theophrastus

Theophrastus , a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age, and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings, and...

and a few doxographers

Doxography

Doxography is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term was coined by the German classical scholar Hermann Alexander Diels.- Classic Greek philosophy :...

provide us with the little information that remains. However, we know from Aristotle that Thales, also from Miletus, precedes Anaximander. It is debatable whether Thales actually was the teacher of Anaximander, but there is no doubt that Anaximander was influenced by Thales' theory that everything is derived from water. One thing that is not debatable is that even the ancient Greeks considered Anaximander to be from the Monist school which began in Miletus with Thales followed by Anaximander and finished with Anaximenes

Anaximenes of Miletus

Anaximenes of Miletus was an Archaic Greek Pre-Socratic philosopher active in the latter half of the 6th century BC. One of the three Milesian philosophers, he is identified as a younger friend or student of Anaximander. Anaximenes, like others in his school of thought, practiced material monism...

. 3rd century Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

rhetorician Aelian

Claudius Aelianus

Claudius Aelianus , often seen as just Aelian, born at Praeneste, was a Roman author and teacher of rhetoric who flourished under Septimius Severus and probably outlived Elagabalus, who died in 222...

depicts him as leader of the Milesian colony to Apollonia

Sozopol

Sozopol is an ancient seaside town located 35 km south of Burgas on the southern Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Today it is one of the major seaside resorts in the country, known for the Apollonia art and film festival that is named after one of the town's ancient names.The busiest times of the year...

on the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

coast, and hence some have inferred that he was a prominent citizen. Indeed, Various History (III, 17) explains that philosophers sometimes also dealt with political matters. It is very likely that leaders of Miletus sent him there as a legislator to create a constitution or simply to maintain the colony’s allegiance.

Theories

Anaximander's theories were influenced by the Greek mythicalGreek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

tradition, and by some ideas of Thales

Thales

Thales of Miletus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor, and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition...

– the father of philosophy – as well as by observations made by older civilizations in the East (especially by the Babylonian astrologists). All these were elaborated rationally. In his desire to find some universal principle, he assumed like traditional religion the existence of a cosmic order and in elaborating his ideas on this he used the old mythical language which ascribed divine control to various spheres of reality. This was a common practice for the Greek philosophers in a society which saw gods everywhere, therefore they could fit their ideas into a tolerably elastic system.

Some scholars saw a gap between the existing mythical and the new rational

Rationalism

In epistemology and in its modern sense, rationalism is "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification" . In more technical terms, it is a method or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive"...

way of thought which is the main characteristic of the archaic period (8th to 6th century BC) in the Greek city states. Because of this, they didn't hesitate to speak for a 'Greek miracle'. But if we follow carefully the course of Anaximander's ideas, we will notice that there was not such an abrupt break as initially appears. The basic elements of nature (water

Water (classical element)

Water is one of the elements in ancient Greek philosophy, in the Asian Indian system Panchamahabhuta, and in the Chinese cosmological and physiological system Wu Xing...

, air

Air (classical element)

Air is often seen as a universal power or pure substance. Its supposed fundamental importance to life can be seen in words such as aspire, inspire, perspire and spirit, all derived from the Latin spirare.-Greek and Roman tradition:...

, fire

Fire (classical element)

Fire has been an important part of all cultures and religions from pre-history to modern day and was vital to the development of civilization. It has been regarded in many different contexts throughout history, but especially as a metaphysical constant of the world.-Greek and Roman tradition:Fire...

, earth

Earth (classical element)

Earth, home and origin of humanity, has often been worshipped in its own right with its own unique spiritual tradition.-European tradition:Earth is one of the four classical elements in ancient Greek philosophy and science. It was commonly associated with qualities of heaviness, matter and the...

) which the first Greek philosophers believed that constituted the universe represent in fact the primordial

Primordial

Primordial may refer to:* Primordial sea . See abiogenesis* Primordial nuclide, nuclides, a few radioactive, that formed before the Earth existed and are stable enough to still occur on Earth...

forces of previous thought. Their collision produced what the mythical tradition had called cosmic harmony. In the old cosmogonies – Hesiod

Hesiod

Hesiod was a Greek oral poet generally thought by scholars to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. His is the first European poetry in which the poet regards himself as a topic, an individual with a distinctive role to play. Ancient authors credited him and...

(8th-7th century BC) and Pherecydes

Pherecydes of Syros

Pherecydes of Syros was a Greek thinker from the island of Syros, of the 6th century BC. Pherecydes authored the Pentemychos or Heptamychos, one of the first attested prose works in Greek literature, which formed an important bridge between mythic and pre-Socratic thought.- Life :Very little is...

(6th century BC) – Zeus

Zeus

In the ancient Greek religion, Zeus was the "Father of Gods and men" who ruled the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father ruled the family. He was the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. His Roman counterpart is Jupiter and his Etruscan counterpart is Tinia.Zeus was the child of Cronus...

establishes his order in the world by destroying the powers which were threatening this harmony, (the Titans). Anaximander claimed that the cosmic order is not monarchic but geometric and this causes the equilibrium of the earth which is lying in the centre of the universe. This is the projection on nature of a new political order and a new space organized around a centre which is the static point of the system in the society as in nature. In this space there is isonomy (equal rights) and all the forces are symmetrical and transferrable. The decisions are now taken by the assembly of demos in the agora

Agora

The Agora was an open "place of assembly" in ancient Greek city-states. Early in Greek history , free-born male land-owners who were citizens would gather in the Agora for military duty or to hear statements of the ruling king or council. Later, the Agora also served as a marketplace where...

which is lying in the middle of the city.

The same rational way of thought led him to introduce the abstract apeiron

Apeiron (cosmology)

Apeiron is a Greek word meaning unlimited, infinite or indefinite from ἀ- a-, "without" and πεῖραρ peirar, "end, limit", the Ionic Greek form of πέρας peras, "end, limit, boundary".-Apeiron as an origin:...

(indefinite, infinite, boundless, unlimited) as an origin of the universe, a concept that is probably influenced by the original Chaos

Chaos (cosmogony)

Chaos refers to the formless or void state preceding the creation of the universe or cosmos in the Greek creation myths, more specifically the initial "gap" created by the original separation of heaven and earth....

(gaping void, abyss, formless state) of the mythical Greek

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

cosmogony

Cosmogony

Cosmogony, or cosmogeny, is any scientific theory concerning the coming into existence or origin of the universe, or about how reality came to be. The word comes from the Greek κοσμογονία , from κόσμος "cosmos, the world", and the root of γίνομαι / γέγονα "to be born, come about"...

from which everything else appeared. It also takes notice of the mutual changes between the four elements. Origin, then, must be something else unlimited in its source, that could create without experiencing decay, so that genesis would never stop.

Apeiron

The bishopBishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

Hippolytus of Rome (I, 5), and the later 6th century Byzantine philosopher Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia, was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for a time to seek refuge in the Persian court, before being allowed back into...

, attribute to Anaximander the earliest use of the word apeíron ( infinite or limitless) to designate the original principle. He was the first philosopher to employ, in a philosophical context, the term arkhế

Arche

Arche is a Greek word with primary senses 'beginning', 'origin' or 'first cause' and 'power', 'sovereignty', 'domination' as extended meanings. This list is extended to 'ultimate underlying substance' and 'ultimate undemonstrable principle'...

, which until then had meant beginning or origin. For him, it became no longer a mere point in time, but a source that could perpetually give birth to whatever will be. The indefiniteness is spatial in early usages as in Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

(indefinite sea) and as in Xenophanes

Xenophanes

of Colophon was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and social and religious critic. Xenophanes life was one of travel, having left Ionia at the age of 25 he continued to travel throughout the Greek world for another 67 years. Some scholars say he lived in exile in Siciliy...

(6th century BC) who said that the earth went down indefinitely (to apeiron) i.e. beyond the imagination or concept of men.

Aristotle writes (Metaphysics

Metaphysics (Aristotle)

Metaphysics is one of the principal works of Aristotle and the first major work of the branch of philosophy with the same name. The principal subject is "being qua being", or being understood as being. It examines what can be asserted about anything that exists just because of its existence and...

, I III 3-4) that the Pre-Socratics

Pre-Socratic philosophy

Pre-Socratic philosophy is Greek philosophy before Socrates . In Classical antiquity, the Presocratic philosophers were called physiologoi...

were searching for the element that constitutes all things. While each pre-Socratic philosopher gave a different answer as to the identity of this element (water

Water (classical element)

Water is one of the elements in ancient Greek philosophy, in the Asian Indian system Panchamahabhuta, and in the Chinese cosmological and physiological system Wu Xing...

for Thales and air

Air (classical element)

Air is often seen as a universal power or pure substance. Its supposed fundamental importance to life can be seen in words such as aspire, inspire, perspire and spirit, all derived from the Latin spirare.-Greek and Roman tradition:...

for Anaximenes), Anaximander understood the beginning or first principle to be an endless, unlimited primordial mass (apeiron), subject to neither old age nor decay, that perpetually yielded fresh materials from which everything we perceive is derived. He proposed the theory of the apeiron in direct response to the earlier theory of his teacher, Thales, who had claimed that the primary substance was water. The notion of temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious concept of immortality and Anaximander's description was in terms appropriate to this conception. This arche is called "eternal and ageless". (Hippolitus I,6,I;DK B2)

For Anaximander, the principle

Principle (chemistry)

In modern chemistry, principles are the constituents of a substance, specifically those that produce a certain quality or effect in the substance, such as a bitter principle, which is any one of the numerous compounds having a bitter taste....

of things, the constituent of all substances, is nothing determined and not an element such as water in Thales' view. Neither is it something halfway between air and water, or between air and fire, thicker than air and fire, or more subtle than water and earth. Anaximander argues that water cannot embrace all of the opposites found in nature — for example, water can only be wet, never dry — and therefore cannot be the one primary substance; nor could any of the other candidates. He postulated the apeiron as a substance that, although not directly perceptible to us, could explain the opposites he saw around him.

Anaximander explains how the four elements

Classical element

Many philosophies and worldviews have a set of classical elements believed to reflect the simplest essential parts and principles of which anything consists or upon which the constitution and fundamental powers of anything are based. Most frequently, classical elements refer to ancient beliefs...

of ancient physics (air

Air (classical element)

Air is often seen as a universal power or pure substance. Its supposed fundamental importance to life can be seen in words such as aspire, inspire, perspire and spirit, all derived from the Latin spirare.-Greek and Roman tradition:...

, earth

Earth (classical element)

Earth, home and origin of humanity, has often been worshipped in its own right with its own unique spiritual tradition.-European tradition:Earth is one of the four classical elements in ancient Greek philosophy and science. It was commonly associated with qualities of heaviness, matter and the...

, water

Water (classical element)

Water is one of the elements in ancient Greek philosophy, in the Asian Indian system Panchamahabhuta, and in the Chinese cosmological and physiological system Wu Xing...

and fire

Fire (classical element)

Fire has been an important part of all cultures and religions from pre-history to modern day and was vital to the development of civilization. It has been regarded in many different contexts throughout history, but especially as a metaphysical constant of the world.-Greek and Roman tradition:Fire...

) are formed, and how Earth and terrestrial beings are formed through their interactions. Unlike other Pre-Socratics, he never defines this principle precisely, and it has generally been understood (e.g., by Aristotle and by Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

) as a sort of primal chaos

Chaos (mythology)

Chaos refers to the formless or void state preceding the creation of the universe or cosmos in the Greek creation myths, more specifically the initial "gap" created by the original separation of heaven and earth....

. According to him, the Universe originates in the separation of opposites in the primordial matter. It embraces the opposites of hot and cold, wet and dry, and directs the movement of things; an entire host of shapes and differences then grow that are found in "all the worlds" (for he believed there were many).

Anaximander maintains that all dying things are returning to the element from which they came (apeiron). The one surviving fragment of Anaximander's writing deals with this matter. Simplicius transmitted it as a quotation, which describes the balanced and mutual changes of the elements:

Whence things have their origin,

Thence also their destruction happens,

According to necessity;

For they give to each other justice and recompense

For their injustice

In conformity with the ordinance of Time.

Simplicius mentions that Anaximander said all these "in poetic terms", meaning that he used the old mythical language. The goddess Justice (Dike

Dike (mythology)

In ancient Greek culture, Dikē was the spirit of moral order and fair judgement based on immemorial custom, in the sense of socially enforced norms and conventional rules. According to Hesiod In ancient Greek culture, Dikē (Greek: Δίκη, English translation: "justice") was the spirit of moral...

) keeps the cosmic order.

This concept of returning to the element of origin was often revisited afterwards, notably by Aristotle, and by the Greek tragedian

Tragedy

Tragedy is a form of art based on human suffering that offers its audience pleasure. While most cultures have developed forms that provoke this paradoxical response, tragedy refers to a specific tradition of drama that has played a unique and important role historically in the self-definition of...

Euripides

Euripides

Euripides was one of the three great tragedians of classical Athens, the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to him but according to the Suda it was ninety-two at most...

: "what comes from earth must return to earth." Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

, in his Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks

Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks

Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks is a publication of an incomplete book by Friedrich Nietzsche. He had a clean copy made from his notes with the intention of publication. The notes were written around 1873. In it he discussed five Greek philosophers from the sixth and fifth centuries B.C....

, stated that Anaximander viewed "...all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance."

Cosmology

Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

explanatory hypotheses considerably distinguishes him from previous cosmology writers such as Hesiod

Hesiod

Hesiod was a Greek oral poet generally thought by scholars to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. His is the first European poetry in which the poet regards himself as a topic, an individual with a distinctive role to play. Ancient authors credited him and...

. It confirms that pre-Socratic philosophers were making an early effort to demythify physical processes. His major contribution to history was writing the oldest prose document about the Universe

Universe

The Universe is commonly defined as the totality of everything that exists, including all matter and energy, the planets, stars, galaxies, and the contents of intergalactic space. Definitions and usage vary and similar terms include the cosmos, the world and nature...

and the origins of life

Life

Life is a characteristic that distinguishes objects that have signaling and self-sustaining processes from those that do not, either because such functions have ceased , or else because they lack such functions and are classified as inanimate...

; for this he is often called the "Father of Cosmology

Cosmology

Cosmology is the discipline that deals with the nature of the Universe as a whole. Cosmologists seek to understand the origin, evolution, structure, and ultimate fate of the Universe at large, as well as the natural laws that keep it in order...

" and founder of astronomy. However, pseudo-Plutarch

Pseudo-Plutarch

Pseudo-Plutarch is the conventional name given to the unknown authors of a number of pseudepigrapha attributed to Plutarch.Some of these works were included in some editions of Plutarch's Moralia...

states that he still viewed celestial bodies as deities.

Anaximander was the first to conceive a mechanical

Mechanics

Mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of physical bodies when subjected to forces or displacements, and the subsequent effects of the bodies on their environment....

model of the world

World

World is a common name for the whole of human civilization, specifically human experience, history, or the human condition in general, worldwide, i.e. anywhere on Earth....

. In his model, the Earth

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and the densest and fifth-largest of the eight planets in the Solar System. It is also the largest of the Solar System's four terrestrial planets...

floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. It remains "in the same place because of its indifference", a point of view that Aristotle considered ingenious, but false, in On the Heavens

On the Heavens

On the Heavens is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings of the terrestrial world...

. Its curious shape is that of a cylinder

Cylinder (geometry)

A cylinder is one of the most basic curvilinear geometric shapes, the surface formed by the points at a fixed distance from a given line segment, the axis of the cylinder. The solid enclosed by this surface and by two planes perpendicular to the axis is also called a cylinder...

with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

Such a model allowed the concept that celestial bodies

Astronomical object

Astronomical objects or celestial objects are naturally occurring physical entities, associations or structures that current science has demonstrated to exist in the observable universe. The term astronomical object is sometimes used interchangeably with astronomical body...

could pass under it. It goes further than Thales’ claim of a world floating on water, for which Thales faced the problem of explaining what would contain this ocean, while Anaximander solved it by introducing his concept of infinite (apeiron).

Temperature

Temperature is a physical property of matter that quantitatively expresses the common notions of hot and cold. Objects of low temperature are cold, while various degrees of higher temperatures are referred to as warm or hot...

, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the occlusion

Occultation

An occultation is an event that occurs when one object is hidden by another object that passes between it and the observer. The word is used in astronomy . It can also refer to any situation wherein an object in the foreground blocks from view an object in the background...

of that hole. The diameter of the solar wheel was twenty-seven times that of the Earth (or twenty-eight, depending on the sources) and the lunar

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

wheel, whose fire was less intense, eighteen (or nineteen) times. Its hole could change shape, thus explaining lunar phase

Lunar phase

A lunar phase or phase of the moon is the appearance of the illuminated portion of the Moon as seen by an observer, usually on Earth. The lunar phases change cyclically as the Moon orbits the Earth, according to the changing relative positions of the Earth, Moon, and Sun...

s. The star

Star

A star is a massive, luminous sphere of plasma held together by gravity. At the end of its lifetime, a star can also contain a proportion of degenerate matter. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun, which is the source of most of the energy on Earth...

s and the planet

Planet

A planet is a celestial body orbiting a star or stellar remnant that is massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity, is not massive enough to cause thermonuclear fusion, and has cleared its neighbouring region of planetesimals.The term planet is ancient, with ties to history, science,...

s, located closer, followed the same model.

Anaximander was the first astronomer to consider the Sun as a huge mass, and consequently, to realize how far from Earth it might be, and the first to present a system where the celestial bodies turned at different distances. Furthermore, according to Diogenes Laertius (II, 2), he built a celestial sphere

Celestial sphere

In astronomy and navigation, the celestial sphere is an imaginary sphere of arbitrarily large radius, concentric with the Earth and rotating upon the same axis. All objects in the sky can be thought of as projected upon the celestial sphere. Projected upward from Earth's equator and poles are the...

. This invention undoubtedly made him the first to realize the obliquity

Axial tilt

In astronomy, axial tilt is the angle between an object's rotational axis, and a line perpendicular to its orbital plane...

of the Zodiac

Zodiac

In astronomy, the zodiac is a circle of twelve 30° divisions of celestial longitude which are centred upon the ecliptic: the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year...

as the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

reports in Natural History (II, 8). It is a little early to use the term ecliptic

Ecliptic

The ecliptic is the plane of the earth's orbit around the sun. In more accurate terms, it is the intersection of the celestial sphere with the ecliptic plane, which is the geometric plane containing the mean orbit of the Earth around the Sun...

, but his knowledge and work on astronomy confirm that he must have observed the inclination of the celestial sphere in relation to the plane of the Earth to explain the seasons. The doxographer

Doxography

Doxography is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term was coined by the German classical scholar Hermann Alexander Diels.- Classic Greek philosophy :...

and theologian Aetius attributes to Pythagoras the exact measurement of the obliquity.

Multiple worlds

According to Simplicius, Anaximander already speculated on the plurality of worlds, similar to atomistsAtomism

Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes...

Leucippus

Leucippus

Leucippus or Leukippos was one of the earliest Greeks to develop the theory of atomism — the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms — which was elaborated in greater detail by his pupil and successor, Democritus...

and Democritus

Democritus

Democritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

, and later philosopher Epicurus

Epicurus

Epicurus was an ancient Greek philosopher and the founder of the school of philosophy called Epicureanism.Only a few fragments and letters remain of Epicurus's 300 written works...

. These thinkers supposed that worlds appeared and disappeared for a while, and that some were born when others perished. They claimed that this movement was eternal, "for without movement, there can be no generation, no destruction".

In addition to Simplicius, Hippolytus reports Anaximander's claim that from the infinite comes the principle of beings, which themselves come from the heavens and the worlds (several doxographers use the plural when this philosopher is referring to the worlds within, which are often infinite in quantity). Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

writes that he attributes different gods to the countless worlds.

This theory places Anaximander close to the Atomists and the Epicureans

Epicureanism

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy based upon the teachings of Epicurus, founded around 307 BC. Epicurus was an atomic materialist, following in the steps of Democritus. His materialism led him to a general attack on superstition and divine intervention. Following Aristippus—about whom...

who, more than a century later, also claimed that an infinity of worlds appeared and disappeared. In the timeline of the Greek history of thought, some thinkers conceptualized a single world (Plato, Aristotle, Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae in Asia Minor, Anaxagoras was the first philosopher to bring philosophy from Ionia to Athens. He attempted to give a scientific account of eclipses, meteors, rainbows, and the sun, which he described as a fiery mass larger than...

and Archelaus

Archelaus (philosopher)

Archelaus was an Ancient Greek philosopher, a pupil of Anaxagoras, and said by some to have been a teacher of Socrates. He asserted that the principle of motion was the separation of hot from cold, from which he endeavoured to explain the formation of the Earth and the creation of animals and...

), while others instead speculated on the existence of a series of worlds, continuous or non-continuous (Anaximenes, Heraclitus, Empedocles

Empedocles

Empedocles was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a citizen of Agrigentum, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for being the originator of the cosmogenic theory of the four Classical elements...

and Diogenes

Diogenes Apolloniates

Diogenes of Apollonia was an ancient Greek philosopher, and was a native of the Milesian colony Apollonia in Thrace. He lived for some time in Athens. His doctrines are known chiefly from Diogenes Laërtius and Simplicius. He believed air to be the one source of all being, and, as a primal force,...

).

Meteorological phenomena

Anaximander attributed some phenomena, such as thunderThunder

Thunder is the sound made by lightning. Depending on the nature of the lightning and distance of the listener, thunder can range from a sharp, loud crack to a long, low rumble . The sudden increase in pressure and temperature from lightning produces rapid expansion of the air surrounding and within...

and lightning

Lightning

Lightning is an atmospheric electrostatic discharge accompanied by thunder, which typically occurs during thunderstorms, and sometimes during volcanic eruptions or dust storms...

, to the intervention of elements, rather than to divine causes. In his system, thunder results from the shock of clouds hitting each other; the loudness of the sound is proportionate with that of the shock. Thunder without lightning is the result of the wind being too weak to emit any flame, but strong enough to produce a sound. A flash of lightning without thunder is a jolt of the air that disperses and falls, allowing a less active fire to break free. Thunderbolts are the result of a thicker and more violent air flow.

He saw the sea as a remnant of the mass of humidity that once surrounded Earth. A part of that mass evaporated under the sun's action, thus causing the winds and even the rotation of the celestial bodies, which he believed were attracted to places where water is more abundant. He explained rain as a product of the humidity pumped up from Earth by the sun. For him, the Earth was slowly drying up and water only remained in the deepest regions, which someday would go dry as well. According to Aristotle's Meteorology

Meteorology (Aristotle)

Meteorology is a treatise by Aristotle which contains his theories about the earth sciences. These include early accounts of water evaporation, weather phenomena, and earthquakes....

(II, 3), Democritus also shared this opinion.

Origin of humankind

Anaximander speculated about the beginnings and originEvolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

of animal life. Taking into account the existence of fossils, he claimed that animals sprang out of the sea long ago. The first animals were born trapped in a spiny bark, but as they got older, the bark would dry up and break. As the early humidity evaporated, dry land emerged and, in time, humankind had to adapt. The 3rd century Roman writer Censorinus

Censorinus

Censorinus, Roman grammarian and miscellaneous writer, flourished during the 3rd century AD.He was the author of a lost work De Accentibus and of an extant treatise De Die Natali, written in 238, and dedicated to his patron Quintus Caerellius as a birthday gift...

reports:

Anaximander put forward the idea that humans had to spend part of this transition inside the mouths of big fish to protect themselves from the Earth's climate until they could come out in open air and lose their scales. He thought that, considering humans' extended infancy, we could not have survived in the primeval world in the same manner we do presently.

Even though he had no theory of natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

, some people consider him as evolution's most ancient proponent. The theory of an aquatic descent of man was re-conceived centuries later as the aquatic ape hypothesis

Aquatic ape hypothesis

The aquatic ape hypothesis is an alternative explanation of some characteristics of human evolution which hypothesizes that the common ancestors of modern humans spent a period of time adapting to life in a partially aquatic environment. The hypothesis is based on differences between humans and...

. These pre-Darwinian concepts may seem strange, considering modern knowledge and scientific methods, because they present complete explanations of the universe while using bold and hard-to-demonstrate hypotheses. However, they illustrate the beginning of a phenomenon sometimes called the "Greek miracle": men try to explain the nature of the world, not with the aid of myths or religion, but with material principles. This is the very principle of scientific thought, which was later advanced further by improved research methods.

Cartography

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

and Agathemerus

Agathemerus

Agathemerus was a Greek geographer who during the Roman Greece period published a small two-part geographical work titled A Sketch of Geography in Epitome , addressed to his pupil Philon. The son of Orthon, Agathemerus is speculated to have lived in the 3rd century...

(later Greek geographers) claim that, according to the geographer Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene was a Greek mathematician, poet, athlete, geographer, astronomer, and music theorist.He was the first person to use the word "geography" and invented the discipline of geography as we understand it...

, Anaximander was the first to publish a map of the world. The map probably inspired the Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus to draw a more accurate version. Strabo viewed both as the first geographers after Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

.

Maps were produced in ancient times, also notably in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, Lydia

Lydia

Lydia was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern Turkish provinces of Manisa and inland İzmir. Its population spoke an Anatolian language known as Lydian....

, the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, and Babylon

Babylon

Babylon was an Akkadian city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which are found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers south of Baghdad...

. Only some small examples survived until today. The unique example of a world map comes from late Babylonian tablet BM 92687 later than 9th century BCE but is based probably on a much older map. These maps indicated directions, roads, towns, borders, and geological features. Anaximander's innovation was to represent the entire inhabited land known to the ancient Greeks.

Such an accomplishment is more significant than it at first appears. Anaximander most likely drew this map for three reasons. First, it could be used to improve navigation and trade between Miletus

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

's colonies and other colonies around the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea. Second, Thales

Thales

Thales of Miletus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor, and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition...

would probably have found it easier to convince the Ionian city-states

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

to join in a federation in order to push the Median

Medes

The MedesThe Medes...

threat away if he possessed such a tool. Finally, the philosophical idea of a global representation of the world simply for the sake of knowledge was reason enough to design one.

Surely aware of the sea's convexity, he may have designed his map on a slightly rounded metal surface. The centre or “navel” of the world ( omphalós gẽs) could have been Delphi

Delphi

Delphi is both an archaeological site and a modern town in Greece on the south-western spur of Mount Parnassus in the valley of Phocis.In Greek mythology, Delphi was the site of the Delphic oracle, the most important oracle in the classical Greek world, and a major site for the worship of the god...

, but is more likely in Anaximander's time to have been located near Miletus. The Aegean Sea

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

was near the map's centre and enclosed by three continents, themselves located in the middle of the ocean and isolated like islands by sea and rivers. Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

was bordered on the south by the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

and was separated from Asia

Asia

Asia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

by the Black Sea, the Lake Maeotis

Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov , known in Classical Antiquity as Lake Maeotis, is a sea on the south of Eastern Europe. It is linked by the narrow Strait of Kerch to the Black Sea to the south and is bounded on the north by Ukraine mainland, on the east by Russia, and on the west by the Ukraine's Crimean...

, and, further east, either by the Phasis River

Rioni River

The Rioni or Rion River is the main river of western Georgia. It originates in the Caucasus Mountains, in the region of Racha and flows west to the Black Sea, entering it north of the city of Poti...

(now called the Rioni) or the Tanais

Tanais

Tanais is the ancient name for the River Don in Russia. Strabo regarded it as the boundary between Europe and Asia.In antiquity, Tanais was also the name of a city in the Don river delta that reaches into the northeasternmost part of the Sea of Azov, which the Greeks called Lake Maeotis...

. The Nile

Nile