Amanita bisporigera

Encyclopedia

Amanita bisporigera is a deadly poisonous

species of fungus

in the Amanitaceae

family. It is commonly known as the eastern North American destroying angel or the destroying angel, although it shares this latter name with three other lethal white Amanita

species, A. ocreata

, A. verna

and A. virosa

. The fruit bodies

are found on the ground in mixed coniferous and deciduous forests of Eastern North America south to Mexico, but are rare in western North America; it has also been found in pine plantations in Colombia

. The mushroom has a smooth white cap

that can reach up to 10 cm (3.9 in) across, and a stem

, up to 14 cm (5.5 in) by 1.8 cm (0.708661417322835 in) thick, that has a delicate white skirt-like ring

near the top. The bulbous stem base is covered with a membranous sac-like volva

. The white gills are free from attachment to the stalk

and crowded closely together. As the species name suggests, A. bisporigera typically bears two spore

s on the basidia, although this characteristic is not as immutable as was once thought.

First described in 1906, A. bisporigera is classified in the section Phalloideae of the genus Amanita together with other amatoxin

-containing species. Amatoxins are cyclic peptide

s which inhibit the enzyme RNA polymerase II

and interfere with various cellular functions. The first symptoms of poisoning appear 6 to 24 hours after consumption, followed by a period of apparent improvement, then by symptoms of liver and kidney failure, and death after four days or more. Amanita bisporigera closely resembles a few other white amanitas, including the equally deadly A. virosa and A. verna. These species, difficult to distinguish from A. bisporigera based on visible field characteristics, do not have two-spored basidia, and do not stain yellow when a dilute solution of potassium hydroxide

is applied. The DNA

of A. bisporigera has been partially sequenced

, and the gene

s responsible for the production of amatoxins have been determined.

colleague Charles E. Lewis. The type locality was Ithaca, New York

, where several collections were made. In his 1941 monograph

of world Amanita species, Jean-Edouard Gilbert transferred the species to his new genus Amanitina, but this genus is now considered synonymous

with Amanita. In 1944, William Murrill

described the species Amanita vernella, collected from Gainesville, Florida

; that species is now thought to be synonymous with A. bisporigera after a 1979 examination of its type material revealed basidia

that were mostly 2-spored. Amanita phalloides var. striatula, a poorly known taxon originally described from the United States in 1902 by Charles Horton Peck

, is considered by Amanita authority Rodham Tulloss to be synonymous with A. bisporigera. Vernacular names

for the mushroom include "destroying angel", "deadly amanita", "white death cap", "angel of death" and "eastern North American destroying angel".

Amanita bisporigera belongs to section Phalloideae of the genus Amanita, which contains some of the deadliest Amanita species, including A. phalloides and A. virosa. This classification has been upheld with phylogenetic analyses, which demonstrate that the toxin-producing members of section Phalloidae form a clade

—that is, they derive from a common ancestor. In 2005, Zhang and colleagues performed a phylogenetic analysis based on the internal transcribed spacer

(ITS) sequences of several white-bodied toxic Amanita species, most of which are found in Asia. Their results support a clade containing A. bisporigera, A. subjunquillea var. alba, A. exitialis, and A. virosa. The Guangzhou destroying angel (Amanita exitialis) has two-spored basidia, like A. bisporigera.

is 3 – in diameter and, depending on its age, ranges in shape from egg-shaped to convex to somewhat flattened. The cap surface is smooth and white, sometimes with a pale tan- or cream-colored tint in the center. The surface is either dry or, when the environment is moist, slightly sticky. The flesh

is thin and white, and does not change color when bruised. The margin of the cap, which is rolled inwards in young specimens, does not have striations (grooves), and lacks volval

remnants. The gills, also white, are crowded closely together. They are either free from attachment to the stem

or just barely reach it. The lamellulae (short gills that do not extend all the way to the stem) are numerous, and gradually narrow.

The white stem is 6 – by 0.7 – thick, solid (i.e., not hollow), and tapers slightly upward. The surface, in young specimens especially, is frequently floccose (covered with tufts of soft hair), fibrillose (covered with small slender fibers), or squamulose (covered with small scales); there may be fine grooves along its length. The bulb at the base of the stem is spherical or nearly so. The delicate ring

on the upper part of the stem is a remnant of the partial veil

that extends from the cap margin to the stalk and covers the gills during development. It is white, thin, membranous, and hangs like a skirt. When young, the mushrooms are enveloped in a membrane called the universal veil

, which stretches from the top of the cap to the bottom of the stem, imparting an oval, egg-like appearance. In mature fruit bodies, the veil's remnants form a membrane around the base, the volva, like an eggshell-shaped cup. On occasion, however, the volva remains underground or gets torn up during development. It is white, sometimes lobed, and may become pressed closely to the stem. The volva is up to 3.8 cm (1.5 in) in height (measured from the base of the bulb), and is about 2 mm thick midway between the top and the base attachment. The mushroom's odor has been described as "pleasant to somewhat nauseous", becoming more cloying as the fruit body ages. The cap flesh turns yellow when a solution of potassium hydroxide (KOH, 5–10%) is applied (a common chemical test used in mushroom identification). This characteristic chemical reaction is shared with A. ocreata and A. virosa, although some authors have expressed doubt about the identity of North American A. virosa, suggesting those collections may represent four-spored A. bisporigera. Tulloss suggests that reports of A. bisporigera that do not turn yellow with KOH were actually based on white forms of A. phalloides. Findings from the Chiricahua Mountains

of Arizona

and in central Mexico, although "nearly identical" to A. bisporigera, do not stain yellow with KOH; their taxonomic status has not been investigated in detail.

of A. bisporigera, like most Amanita, is white. The spore

s are roughly spherical, thin-walled, hyaline

(translucent), amyloid

, and measure 7.8–9.6 by 7.0–9.0 μm

. The cap cuticle

is made of partially gelatinized, filamentous interwoven hypha

e, 2–6 μm in diameter. The tissue of the gill is bilateral, meaning it diverges from the center of the gill to its outer edge. The subhymenium is ramose—composed of relatively thin branching, unclamped hyphae. The spore-bearing cells, the basidia, are club-shaped, thin-walled, without clamps, with dimensions of 34–45 by 4–11 μm. They are typically two-spored, although rarely three- or four-spored forms have been found. Although the two-spored basidia are a defining characteristic of the species, there is evidence of a tendency to shift towards producing four-spored basidia as the fruiting season progresses. The volva is composed almost exclusively of densely interwoven filamentous hyphae, 2–10 μm in diameter, that are sparsely to moderately branched. There are few small inflated cells, which are mostly spherical to broadly elliptic. The tissue of the stem is made of abundant, sparsely branched, filamentous hyphae, without clamps, measuring 2–5 μm in diameter. The inflated cells are club-shaped, longitudinally oriented, and up to 2–3 by 15.7 μm. The annulus is made of abundant moderately branched filamentous hyphae, measuring 2–6 μm in diameter. The inflated cells are sparse, broadly elliptic to pear-shaped, and are rarely larger than 31 by 22 μm. Pleurocystidia and cheilocystidia (cystidia found on the gill faces and edges, respectively) are absent, but there may be cylindrical to sac-like cells of the partial veil on the gill edges; these cells are hyaline and measure 24–34 by 7–16 μm.

In 1906 Charles E. Lewis studied and illustrated the development of the basidia in order to compare the nuclear

behavior of the two-spored with that of the four-spored forms. Initially (1), the young basidium, appearing as a club-shaped branch from the subhymenium, is filled with cytoplasm

and contains two primary nuclei, which have distinct nucleoli

. As the basidium grows larger, the membranes of the two nuclei contact (2), and then the membrane disappears at the point of contact (3). The two primary nuclei remain distinct for a short time, but eventually the two nuclei fuse completely to form a larger secondary nucleus with a single secondary nucleolus (4, 5). The basidium increases in size after the primary nuclei fuse, and the nucleus migrates towards the end of the basidia (6, 7). During this time, the nucleus develops vacuole

s "filled by the nuclear sap in the living cell". Chromosome

s are produced from the nucleolar threads, and align transversely near the apex of the basidium, connected by spindles (8–10). The chromosomes then move to the poles, forming the daughter nuclei that occupy different positions in the basidium; the daughters now have a structure similar to that of the parent nuclei (11). The two nuclei then divide to form four nuclei, similar to fungi with four-spored basidia (12, 13). The four nuclei crowd together at some distance from the end of the basidium to form an irregular mass (14). Shortly thereafter, the sterigmata (slender projections of the basidia that attach the spores) begin to form (15), and cytoplasm begins to pass through the sterigmata to form the spores (16). Although Lewis was not able to clearly determine from observation alone whether the contents of two or four nuclei passed through the sterigmata, he deduced, by examining older basidia with mature spores, that only two nuclei enter the spores (16, 17).

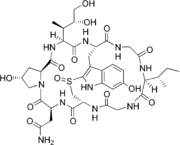

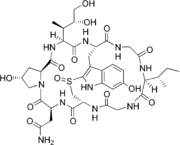

Amanita bisporigera is considered the most toxic North American Amanita mushroom, with little variation in toxin content between different fruit bodies. Three subtypes of amatoxin have been described: α-

Amanita bisporigera is considered the most toxic North American Amanita mushroom, with little variation in toxin content between different fruit bodies. Three subtypes of amatoxin have been described: α-

, β

, and γ-amanitin

. The principal amatoxin, α-amanitin, is readily absorbed across the intestine, and 60% of the absorbed toxin is excreted into bile

and undergoes enterohepatic circulation

; the kidneys clear the remaining 40%. The toxin inhibits the enzyme RNA polymerase II

, thereby interfering with DNA transcription, which suppresses RNA production and protein synthesis. This causes cellular necrosis

, especially in cells which are initially exposed and have rapid rates of protein synthesis. This process results in severe acute liver dysfunction and, ultimately, liver failure

. Amatoxins are not broken down by boiling, freezing, or drying. Roughly 0.2 to 0.4 milligrams of α-amanitin is present in 1 gram of A. bisporigera; the lethal dose

in humans is less than 0.1 mg/kg body weight. One mature fruit body can contain 10–12 mg of α-amanitin, enough for a lethal dose. The α-amanitin concentration in the spores is about 17% that of the fruit body tissues. A. bisporigera also contains the phallotoxin

phallacidin, structurally related to the amatoxins but considered less poisonous because of poor absorption. Poisonings (from similar white amanitas) have also been reported in domestic animals, including dogs, cats, and cows.

The first reported poisonings resulting in death from the consumption of A. bisporigera were from near San Antonio, Mexico in 1957, where a rancher, his wife, and three children consumed the fungus; only the man survived. Amanita poisoning is characterized by the following distinct stages: The incubation stage is an asymptomatic

period which ranges from 6 to 12 hours after ingestion. In the gastrointestinal stage, about 6 to 16 hours after ingestion, there is onset of abdominal pain, explosive vomiting, and diarrhea for up to 24 hours, which may lead to dehydration, severe electrolyte

imbalances, and shock. These early symptoms may be related to other toxins such as phalloidin

. In the cytotoxic stage, 24 to 48 hours after ingestion, clinical and biochemical signs of liver damage are observed, but the patient is typically free of gastrointestinal symptoms. The signs of liver dysfunction such as jaundice

, hypoglycemia

, acidosis

, and hemorrhage appear. Later, there is an increase in the levels of prothrombin and blood levels of ammonia

, and the signs of hepatic encephalopathy

and/or kidney failure appear. The risk factor

s for mortality that have been reported are age younger than 10 years, short latency period between ingestion and onset of symptoms, severe coagulopathy

(blood clotting disorder), severe hyperbilirubinemia (jaundice), and rising serum creatinine

levels.

and A. virosa

. A. bisporigera is at times smaller and more slender than either A. verna or A. virosa, but it varies considerably in size; therefore size is not a reliable diagnostic characteristic. A. virosa fruits in autumn—later than A. bisporigera. A. elliptosperma

is less common but widely distributed in the southeastern United States, while A. ocreata

is found on the West Coast

and in the Southwest. Other similar toxic North American species include Amanita magnivelaris

, which has a cream-colored, rather thick, felted-submembranous, skirt-like ring, and A. virosiformis

, which has elongated spores that are 3.9–4.7 by 11.7–13.4 μm. Neither A. elliptosperma nor A. magnivelaris typically turn yellow with the application of KOH; the KOH reaction of A. virosiformis has not been reported.

Leucoagaricus leucothites is another all-white mushroom with an annulus, free gills, and white spore print, but it lacks a volva and has thick-walled dextrinoid (staining red-brown in Melzer's reagent

) egg-shaped spores with a pore. A. bisporigera may also be confused with the larger edible

species Agaricus silvicola

, the "horse-mushroom". Like many white amanitas, young fruit bodies of A. bisporigera, still enveloped in the universal veil, can be confused with puffball

species, but a longitudinal cut of the fruit body reveals internal structures in the Amanita that are absent in puffballs. In 2006, seven members of the Hmong

community living in Minnesota were poisoned with A. bisporigera because they had confused it with edible paddy straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea

) that grow in Southeast Asia.

coniferous and deciduous forests; they tend to appear during summer and early fall. The fruit bodies are commonly found near oak

, but have been reported in birch

-aspen

areas in the west. It is most commonly found in eastern North America, and in rare is western North America. It is widely distributed in Canada, and the distribution extends south to Mexico. The species has been found in Colombia

, where it may have been exported in pine plantation

s.

in 2004 as part of their ongoing studies of Amanita bisporigera. The purpose of the project is to determine the gene

s and genetic controls associated with the formation of mycorrhizae, and to elucidate the biochemical mechanisms of toxin production. The genome

of A. bisporigera has been sequenced using a combination of automated Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing

, and the genome sequence information is publicly searchable. The sequence data enabled the researchers to identify the genes responsible for amatoxin and phallotoxin biosynthesis, AMA1 and PHA1. The cyclic peptides are synthesized on ribosomes, and require proline

-specific peptidases from the prolyl oligopeptidase family for processing

.

The genetic sequence information from A. bisporigera has been used to identify molecular polymorphisms

in the related A. phalloides. These single-nucleotide polymorphisms may be used as population genetic marker

s to study phylogeography

and population genetics

. Sequence information has also been employed to show that A. bisporigera lacks many of the major classes of secreted enzymes that break down the complex polysaccharide

s of plant cell walls, like cellulose

. In contrast, saprobic fungi like Coprinopsis cinerea

and Galerina marginata

, which break down organic matter

to obtain nutrients, have a more complete complement of cell wall-degrading enzymes. Although few ectomycorrhizal fungi have yet been tested in this way, the authors suggest that the absence of plant cell wall-degrading ability may correlate with the ectomycorrhizal ecological niche.

Mushroom poisoning

Mushroom poisoning refers to harmful effects from ingestion of toxic substances present in a mushroom. These symptoms can vary from slight gastrointestinal discomfort to death. The toxins present are secondary metabolites produced in specific biochemical pathways in the fungal cells...

species of fungus

Fungus

A fungus is a member of a large group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds , as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, Fungi, which is separate from plants, animals, and bacteria...

in the Amanitaceae

Amanitaceae

Amanitaceae are a family of fungi or mushrooms. The family, also commonly called the Amanita family, is in order Agaricales, gilled mushrooms...

family. It is commonly known as the eastern North American destroying angel or the destroying angel, although it shares this latter name with three other lethal white Amanita

Amanita

The genus Amanita contains about 600 species of agarics including some of the most toxic known mushrooms found worldwide. This genus is responsible for approximately 95% of the fatalities resulting from mushroom poisoning, with the death cap accounting for about 50% on its own...

species, A. ocreata

Amanita ocreata

Amanita ocreata, commonly known as the death angel, destroying angel, angel of death or more precisely Western North American destroying angel, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in the Pacific Northwest and California floristic provinces of...

, A. verna

Amanita verna

Amanita verna, commonly known as the fool's mushroom, Destroying angel or the mushroom fool, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in Europe in spring, A. verna associates with various deciduous and coniferous trees...

and A. virosa

Amanita virosa

Amanita virosa, commonly known as the European destroying angel, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in Europe, A. virosa associates with various deciduous and coniferous trees...

. The fruit bodies

Basidiocarp

In fungi, a basidiocarp, basidiome or basidioma , is the sporocarp of a basidiomycete, the multicellular structure on which the spore-producing hymenium is borne. Basidiocarps are characteristic of the hymenomycetes; rusts and smuts do not produce such structures...

are found on the ground in mixed coniferous and deciduous forests of Eastern North America south to Mexico, but are rare in western North America; it has also been found in pine plantations in Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

. The mushroom has a smooth white cap

Pileus (mycology)

The pileus is the technical name for the cap, or cap-like part, of a basidiocarp or ascocarp that supports a spore-bearing surface, the hymenium. The hymenium may consist of lamellae, tubes, or teeth, on the underside of the pileus...

that can reach up to 10 cm (3.9 in) across, and a stem

Stipe (mycology)

thumb|150px|right|Diagram of a [[basidiomycete]] stipe with an [[annulus |annulus]] and [[volva |volva]]In mycology a stipe refers to the stem or stalk-like feature supporting the cap of a mushroom. Like all tissues of the mushroom other than the hymenium, the stipe is composed of sterile hyphal...

, up to 14 cm (5.5 in) by 1.8 cm (0.708661417322835 in) thick, that has a delicate white skirt-like ring

Annulus (mycology)

An annulus is the ring like structure sometimes found on the stipe of some species of mushrooms. The annulus represents the remaining part of the partial veil, after it has ruptured to expose the gills or other spore-producing surface. An annulus may be thick and membranous, or it may be cobweb-like...

near the top. The bulbous stem base is covered with a membranous sac-like volva

Volva (mycology)

The volva is a mycological term to describe a cup-like structure at the base of a mushroom that is a remnant of the universal veil. This macrofeature is important in wild mushroom identification due to it being an easily observed, taxonomically significant feature which frequently signifies a...

. The white gills are free from attachment to the stalk

Stipe (mycology)

thumb|150px|right|Diagram of a [[basidiomycete]] stipe with an [[annulus |annulus]] and [[volva |volva]]In mycology a stipe refers to the stem or stalk-like feature supporting the cap of a mushroom. Like all tissues of the mushroom other than the hymenium, the stipe is composed of sterile hyphal...

and crowded closely together. As the species name suggests, A. bisporigera typically bears two spore

Spore

In biology, a spore is a reproductive structure that is adapted for dispersal and surviving for extended periods of time in unfavorable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many bacteria, plants, algae, fungi and some protozoa. According to scientist Dr...

s on the basidia, although this characteristic is not as immutable as was once thought.

First described in 1906, A. bisporigera is classified in the section Phalloideae of the genus Amanita together with other amatoxin

Amatoxin

Amatoxins are a subgroup of at least eight toxic compounds found in several genera of poisonous mushrooms, most notably Amanita phalloides and several other members of the genus Amanita, as well as some Conocybe, Galerina and Lepiota mushroom species.-Structure:The compounds have a similar...

-containing species. Amatoxins are cyclic peptide

Cyclic peptide

Cyclic peptides are polypeptide chains whose amino and carboxyl termini are themselves linked together with a peptide bond that forms a circular chain. A number of cyclic peptides have been discovered in nature and they can range anywhere from just a few amino acids in length, to hundreds...

s which inhibit the enzyme RNA polymerase II

RNA polymerase II

RNA polymerase II is an enzyme found in eukaryotic cells. It catalyzes the transcription of DNA to synthesize precursors of mRNA and most snRNA and microRNA. A 550 kDa complex of 12 subunits, RNAP II is the most studied type of RNA polymerase...

and interfere with various cellular functions. The first symptoms of poisoning appear 6 to 24 hours after consumption, followed by a period of apparent improvement, then by symptoms of liver and kidney failure, and death after four days or more. Amanita bisporigera closely resembles a few other white amanitas, including the equally deadly A. virosa and A. verna. These species, difficult to distinguish from A. bisporigera based on visible field characteristics, do not have two-spored basidia, and do not stain yellow when a dilute solution of potassium hydroxide

Potassium hydroxide

Potassium hydroxide is an inorganic compound with the formula KOH, commonly called caustic potash.Along with sodium hydroxide , this colorless solid is a prototypical strong base. It has many industrial and niche applications. Most applications exploit its reactivity toward acids and its corrosive...

is applied. The DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

of A. bisporigera has been partially sequenced

DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing includes several methods and technologies that are used for determining the order of the nucleotide bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine—in a molecule of DNA....

, and the gene

Gene

A gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

s responsible for the production of amatoxins have been determined.

Taxonomy, classification, and phylogeny

Amanita bisporigera was first described scientifically in 1906 by American botanist George Francis Atkinson in a publication by Cornell UniversityCornell University

Cornell University is an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, United States. It is a private land-grant university, receiving annual funding from the State of New York for certain educational missions...

colleague Charles E. Lewis. The type locality was Ithaca, New York

Ithaca, New York

The city of Ithaca, is a city in upstate New York and the county seat of Tompkins County, as well as the largest community in the Ithaca-Tompkins County metropolitan area...

, where several collections were made. In his 1941 monograph

Monograph

A monograph is a work of writing upon a single subject, usually by a single author.It is often a scholarly essay or learned treatise, and may be released in the manner of a book or journal article. It is by definition a single document that forms a complete text in itself...

of world Amanita species, Jean-Edouard Gilbert transferred the species to his new genus Amanitina, but this genus is now considered synonymous

Synonym (taxonomy)

In scientific nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that is or was used for a taxon of organisms that also goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linnaeus was the first to give a scientific name to the Norway spruce, which he called Pinus abies...

with Amanita. In 1944, William Murrill

William Murrill

William Alphonso Murrill was an American mycologist, known for his contributions to the knowledge of the Agaricales and Polyporaceae.- Education :...

described the species Amanita vernella, collected from Gainesville, Florida

Gainesville, Florida

Gainesville is the largest city in, and the county seat of, Alachua County, Florida, United States as well as the principal city of the Gainesville, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area . The preliminary 2010 Census population count for Gainesville is 124,354. Gainesville is home to the sixth...

; that species is now thought to be synonymous with A. bisporigera after a 1979 examination of its type material revealed basidia

Basidium

thumb|right|500px|Schematic showing a basidiomycete mushroom, gill structure, and spore-bearing basidia on the gill margins.A basidium is a microscopic, spore-producing structure found on the hymenophore of fruiting bodies of basidiomycete fungi. The presence of basidia is one of the main...

that were mostly 2-spored. Amanita phalloides var. striatula, a poorly known taxon originally described from the United States in 1902 by Charles Horton Peck

Charles Horton Peck

Charles Horton Peck, born March 30, 1833 in Sand Lake, New York, died 1917 in Albany, New York, was an American mycologist of the 19th and early 20th centuries...

, is considered by Amanita authority Rodham Tulloss to be synonymous with A. bisporigera. Vernacular names

Common name

A common name of a taxon or organism is a name in general use within a community; it is often contrasted with the scientific name for the same organism...

for the mushroom include "destroying angel", "deadly amanita", "white death cap", "angel of death" and "eastern North American destroying angel".

Amanita bisporigera belongs to section Phalloideae of the genus Amanita, which contains some of the deadliest Amanita species, including A. phalloides and A. virosa. This classification has been upheld with phylogenetic analyses, which demonstrate that the toxin-producing members of section Phalloidae form a clade

Clade

A clade is a group consisting of a species and all its descendants. In the terms of biological systematics, a clade is a single "branch" on the "tree of life". The idea that such a "natural group" of organisms should be grouped together and given a taxonomic name is central to biological...

—that is, they derive from a common ancestor. In 2005, Zhang and colleagues performed a phylogenetic analysis based on the internal transcribed spacer

Internal transcribed spacer

ITS refers to a piece of non-functional RNA situated between structural ribosomal RNAs on a common precursor transcript. Read from 5' to 3', this polycistronic rRNA precursor transcript contains the 5' external transcribed sequence , 18S rRNA, ITS1, 5.8S rRNA, ITS2, 28S rRNA and finally the 3'ETS...

(ITS) sequences of several white-bodied toxic Amanita species, most of which are found in Asia. Their results support a clade containing A. bisporigera, A. subjunquillea var. alba, A. exitialis, and A. virosa. The Guangzhou destroying angel (Amanita exitialis) has two-spored basidia, like A. bisporigera.

Description

The capPileus (mycology)

The pileus is the technical name for the cap, or cap-like part, of a basidiocarp or ascocarp that supports a spore-bearing surface, the hymenium. The hymenium may consist of lamellae, tubes, or teeth, on the underside of the pileus...

is 3 – in diameter and, depending on its age, ranges in shape from egg-shaped to convex to somewhat flattened. The cap surface is smooth and white, sometimes with a pale tan- or cream-colored tint in the center. The surface is either dry or, when the environment is moist, slightly sticky. The flesh

Trama (mycology)

In mycology trama is a term for the inner, fleshy portion of a mushroom's basidiocarp, or fruit body. It is distinct from the outer layer of tissue, known as the pileipellis or cuticle, and from the spore-bearing tissue layer known as the hymenium....

is thin and white, and does not change color when bruised. The margin of the cap, which is rolled inwards in young specimens, does not have striations (grooves), and lacks volval

Volva (mycology)

The volva is a mycological term to describe a cup-like structure at the base of a mushroom that is a remnant of the universal veil. This macrofeature is important in wild mushroom identification due to it being an easily observed, taxonomically significant feature which frequently signifies a...

remnants. The gills, also white, are crowded closely together. They are either free from attachment to the stem

Stipe (mycology)

thumb|150px|right|Diagram of a [[basidiomycete]] stipe with an [[annulus |annulus]] and [[volva |volva]]In mycology a stipe refers to the stem or stalk-like feature supporting the cap of a mushroom. Like all tissues of the mushroom other than the hymenium, the stipe is composed of sterile hyphal...

or just barely reach it. The lamellulae (short gills that do not extend all the way to the stem) are numerous, and gradually narrow.

The white stem is 6 – by 0.7 – thick, solid (i.e., not hollow), and tapers slightly upward. The surface, in young specimens especially, is frequently floccose (covered with tufts of soft hair), fibrillose (covered with small slender fibers), or squamulose (covered with small scales); there may be fine grooves along its length. The bulb at the base of the stem is spherical or nearly so. The delicate ring

Annulus (mycology)

An annulus is the ring like structure sometimes found on the stipe of some species of mushrooms. The annulus represents the remaining part of the partial veil, after it has ruptured to expose the gills or other spore-producing surface. An annulus may be thick and membranous, or it may be cobweb-like...

on the upper part of the stem is a remnant of the partial veil

Partial veil

thumb|150px|right|Developmental stages of [[Agaricus campestris]] showing the role and evolution of a partial veilPartial veil is a mycological term used to describe a temporary structure of tissue found on the fruiting bodies of some basidiomycete fungi, typically agarics...

that extends from the cap margin to the stalk and covers the gills during development. It is white, thin, membranous, and hangs like a skirt. When young, the mushrooms are enveloped in a membrane called the universal veil

Universal veil

In mycology, a universal veil is a temporary membranous tissue that fully envelops immature fruiting bodies of certain gilled mushrooms. The developing Caesar's mushroom , for example, which may resemble a small white sphere at this point, is protected by this structure...

, which stretches from the top of the cap to the bottom of the stem, imparting an oval, egg-like appearance. In mature fruit bodies, the veil's remnants form a membrane around the base, the volva, like an eggshell-shaped cup. On occasion, however, the volva remains underground or gets torn up during development. It is white, sometimes lobed, and may become pressed closely to the stem. The volva is up to 3.8 cm (1.5 in) in height (measured from the base of the bulb), and is about 2 mm thick midway between the top and the base attachment. The mushroom's odor has been described as "pleasant to somewhat nauseous", becoming more cloying as the fruit body ages. The cap flesh turns yellow when a solution of potassium hydroxide (KOH, 5–10%) is applied (a common chemical test used in mushroom identification). This characteristic chemical reaction is shared with A. ocreata and A. virosa, although some authors have expressed doubt about the identity of North American A. virosa, suggesting those collections may represent four-spored A. bisporigera. Tulloss suggests that reports of A. bisporigera that do not turn yellow with KOH were actually based on white forms of A. phalloides. Findings from the Chiricahua Mountains

Chiricahua Mountains

The Chiricahua Mountains are a mountain range in southeastern Arizona which are part of the Basin and Range province of the southwest, and part of the Coronado National Forest...

of Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

and in central Mexico, although "nearly identical" to A. bisporigera, do not stain yellow with KOH; their taxonomic status has not been investigated in detail.

Microscopic features

The spore printSpore print

thumb|300px|right|Making a spore print of the mushroom Volvariella volvacea shown in composite: mushroom cap laid on white and dark paper; cap removed after 24 hours showing pinkish-tan spore print...

of A. bisporigera, like most Amanita, is white. The spore

Spore

In biology, a spore is a reproductive structure that is adapted for dispersal and surviving for extended periods of time in unfavorable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many bacteria, plants, algae, fungi and some protozoa. According to scientist Dr...

s are roughly spherical, thin-walled, hyaline

Hyaline

The term hyaline denotes a substance with a glass-like appearance.-Histopathology:In histopathological medical usage, a hyaline substance appears glassy and pink after being stained with haematoxylin and eosin — usually it is an acellular, proteinaceous material...

(translucent), amyloid

Amyloid (mycology)

In mycology the term amyloid refers to a crude chemical test using iodine in either Melzer's reagent or Lugol's solution, to produce a black to blue-black positive reaction. It is called amyloid because starch gives a similar reaction, and that reaction for starch is also called an amyloid reaction...

, and measure 7.8–9.6 by 7.0–9.0 μm

Micrometre

A micrometer , is by definition 1×10-6 of a meter .In plain English, it means one-millionth of a meter . Its unit symbol in the International System of Units is μm...

. The cap cuticle

Pileipellis

thumb|300px||right|The cuticle of some mushrooms, such as [[Russula mustelina]] shown here, can be peeled from the cap, and may be useful as an identification feature....

is made of partially gelatinized, filamentous interwoven hypha

Hypha

A hypha is a long, branching filamentous structure of a fungus, and also of unrelated Actinobacteria. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium; yeasts are unicellular fungi that do not grow as hyphae.-Structure:A hypha consists of one or...

e, 2–6 μm in diameter. The tissue of the gill is bilateral, meaning it diverges from the center of the gill to its outer edge. The subhymenium is ramose—composed of relatively thin branching, unclamped hyphae. The spore-bearing cells, the basidia, are club-shaped, thin-walled, without clamps, with dimensions of 34–45 by 4–11 μm. They are typically two-spored, although rarely three- or four-spored forms have been found. Although the two-spored basidia are a defining characteristic of the species, there is evidence of a tendency to shift towards producing four-spored basidia as the fruiting season progresses. The volva is composed almost exclusively of densely interwoven filamentous hyphae, 2–10 μm in diameter, that are sparsely to moderately branched. There are few small inflated cells, which are mostly spherical to broadly elliptic. The tissue of the stem is made of abundant, sparsely branched, filamentous hyphae, without clamps, measuring 2–5 μm in diameter. The inflated cells are club-shaped, longitudinally oriented, and up to 2–3 by 15.7 μm. The annulus is made of abundant moderately branched filamentous hyphae, measuring 2–6 μm in diameter. The inflated cells are sparse, broadly elliptic to pear-shaped, and are rarely larger than 31 by 22 μm. Pleurocystidia and cheilocystidia (cystidia found on the gill faces and edges, respectively) are absent, but there may be cylindrical to sac-like cells of the partial veil on the gill edges; these cells are hyaline and measure 24–34 by 7–16 μm.

In 1906 Charles E. Lewis studied and illustrated the development of the basidia in order to compare the nuclear

Cell nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in eukaryotic cells. It contains most of the cell's genetic material, organized as multiple long linear DNA molecules in complex with a large variety of proteins, such as histones, to form chromosomes. The genes within these...

behavior of the two-spored with that of the four-spored forms. Initially (1), the young basidium, appearing as a club-shaped branch from the subhymenium, is filled with cytoplasm

Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is a small gel-like substance residing between the cell membrane holding all the cell's internal sub-structures , except for the nucleus. All the contents of the cells of prokaryote organisms are contained within the cytoplasm...

and contains two primary nuclei, which have distinct nucleoli

Nucleolus

The nucleolus is a non-membrane bound structure composed of proteins and nucleic acids found within the nucleus. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed and assembled within the nucleolus...

. As the basidium grows larger, the membranes of the two nuclei contact (2), and then the membrane disappears at the point of contact (3). The two primary nuclei remain distinct for a short time, but eventually the two nuclei fuse completely to form a larger secondary nucleus with a single secondary nucleolus (4, 5). The basidium increases in size after the primary nuclei fuse, and the nucleus migrates towards the end of the basidia (6, 7). During this time, the nucleus develops vacuole

Vacuole

A vacuole is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in all plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic molecules including enzymes in solution, though in certain...

s "filled by the nuclear sap in the living cell". Chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

s are produced from the nucleolar threads, and align transversely near the apex of the basidium, connected by spindles (8–10). The chromosomes then move to the poles, forming the daughter nuclei that occupy different positions in the basidium; the daughters now have a structure similar to that of the parent nuclei (11). The two nuclei then divide to form four nuclei, similar to fungi with four-spored basidia (12, 13). The four nuclei crowd together at some distance from the end of the basidium to form an irregular mass (14). Shortly thereafter, the sterigmata (slender projections of the basidia that attach the spores) begin to form (15), and cytoplasm begins to pass through the sterigmata to form the spores (16). Although Lewis was not able to clearly determine from observation alone whether the contents of two or four nuclei passed through the sterigmata, he deduced, by examining older basidia with mature spores, that only two nuclei enter the spores (16, 17).

Toxicity

Alpha-amanitin

alpha-Amanitin or α-amanitin is a cyclic peptide of eight amino acids. It is possibly the most deadly of all the amatoxins, toxins found in several species of the Amanita genus of mushrooms, one being the Death cap as well as the Destroying angel, a complex of similar species, principally A....

, β

Beta-amanitin

beta-Amanitin or β-amanitin is a cyclic peptide of eight amino acids. It is an amatoxin, a group of toxins isolated from and found in several members of the Amanita genus of mushrooms, one being the Death cap as well as the Destroying angel, a complex of similar species, principally A. virosa...

, and γ-amanitin

Gamma-amanitin

gamma-Amanitin or γ-amanitin is a cyclic peptide of eight amino acids. It is an amatoxin, a group of toxins isolated from and found in several members of the Amanita genus of mushrooms, one being the Death cap as well as the Destroying angel, a complex of similar species, principally...

. The principal amatoxin, α-amanitin, is readily absorbed across the intestine, and 60% of the absorbed toxin is excreted into bile

Bile

Bile or gall is a bitter-tasting, dark green to yellowish brown fluid, produced by the liver of most vertebrates, that aids the process of digestion of lipids in the small intestine. In many species, bile is stored in the gallbladder and upon eating is discharged into the duodenum...

and undergoes enterohepatic circulation

Enterohepatic circulation

Enterohepatic circulation refers to the circulation of biliary acids from the liver, where they are produced and secreted in the bile, to the small intestine, where it aids in digestion of fats and other substances, back to the liver....

; the kidneys clear the remaining 40%. The toxin inhibits the enzyme RNA polymerase II

RNA polymerase II

RNA polymerase II is an enzyme found in eukaryotic cells. It catalyzes the transcription of DNA to synthesize precursors of mRNA and most snRNA and microRNA. A 550 kDa complex of 12 subunits, RNAP II is the most studied type of RNA polymerase...

, thereby interfering with DNA transcription, which suppresses RNA production and protein synthesis. This causes cellular necrosis

Necrosis

Necrosis is the premature death of cells in living tissue. Necrosis is caused by factors external to the cell or tissue, such as infection, toxins, or trauma. This is in contrast to apoptosis, which is a naturally occurring cause of cellular death...

, especially in cells which are initially exposed and have rapid rates of protein synthesis. This process results in severe acute liver dysfunction and, ultimately, liver failure

Liver failure

Acute liver failure is the appearance of severe complications rapidly after the first signs of liver disease , and indicates that the liver has sustained severe damage . The complications are hepatic encephalopathy and impaired protein synthesis...

. Amatoxins are not broken down by boiling, freezing, or drying. Roughly 0.2 to 0.4 milligrams of α-amanitin is present in 1 gram of A. bisporigera; the lethal dose

Lethal dose

A lethal dose is an indication of the lethality of a given substance or type of radiation. Because resistance varies from one individual to another, the 'lethal dose' represents a dose at which a given percentage of subjects will die...

in humans is less than 0.1 mg/kg body weight. One mature fruit body can contain 10–12 mg of α-amanitin, enough for a lethal dose. The α-amanitin concentration in the spores is about 17% that of the fruit body tissues. A. bisporigera also contains the phallotoxin

Phallotoxin

The phallotoxins consist of at least seven compounds, all of which are bicyclic heptapeptides , isolated from the death cap . Phalloidin had been isolated in 1937 by Feodor Lynen, Heinrich Wieland's student and son-in-law, and Ulrich Wieland of the University of Munich...

phallacidin, structurally related to the amatoxins but considered less poisonous because of poor absorption. Poisonings (from similar white amanitas) have also been reported in domestic animals, including dogs, cats, and cows.

The first reported poisonings resulting in death from the consumption of A. bisporigera were from near San Antonio, Mexico in 1957, where a rancher, his wife, and three children consumed the fungus; only the man survived. Amanita poisoning is characterized by the following distinct stages: The incubation stage is an asymptomatic

Asymptomatic

In medicine, a disease is considered asymptomatic if a patient is a carrier for a disease or infection but experiences no symptoms. A condition might be asymptomatic if it fails to show the noticeable symptoms with which it is usually associated. Asymptomatic infections are also called subclinical...

period which ranges from 6 to 12 hours after ingestion. In the gastrointestinal stage, about 6 to 16 hours after ingestion, there is onset of abdominal pain, explosive vomiting, and diarrhea for up to 24 hours, which may lead to dehydration, severe electrolyte

Electrolyte

In chemistry, an electrolyte is any substance containing free ions that make the substance electrically conductive. The most typical electrolyte is an ionic solution, but molten electrolytes and solid electrolytes are also possible....

imbalances, and shock. These early symptoms may be related to other toxins such as phalloidin

Phalloidin

Phalloidin is one of a group of toxins from the death cap known as phallotoxins.-Background:Pioneering work on this toxin was done by the Nobel laureate Heinrich Wieland in the 1930s...

. In the cytotoxic stage, 24 to 48 hours after ingestion, clinical and biochemical signs of liver damage are observed, but the patient is typically free of gastrointestinal symptoms. The signs of liver dysfunction such as jaundice

Jaundice

Jaundice is a yellowish pigmentation of the skin, the conjunctival membranes over the sclerae , and other mucous membranes caused by hyperbilirubinemia . This hyperbilirubinemia subsequently causes increased levels of bilirubin in the extracellular fluid...

, hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia or hypoglycæmia is the medical term for a state produced by a lower than normal level of blood glucose. The term literally means "under-sweet blood"...

, acidosis

Acidosis

Acidosis is an increased acidity in the blood and other body tissue . If not further qualified, it usually refers to acidity of the blood plasma....

, and hemorrhage appear. Later, there is an increase in the levels of prothrombin and blood levels of ammonia

Ammonia

Ammonia is a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . It is a colourless gas with a characteristic pungent odour. Ammonia contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to food and fertilizers. Ammonia, either directly or...

, and the signs of hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is the occurrence of confusion, altered level of consciousness and coma as a result of liver failure. In the advanced stages it is called hepatic coma or coma hepaticum...

and/or kidney failure appear. The risk factor

Risk factor

In epidemiology, a risk factor is a variable associated with an increased risk of disease or infection. Sometimes, determinant is also used, being a variable associated with either increased or decreased risk.-Correlation vs causation:...

s for mortality that have been reported are age younger than 10 years, short latency period between ingestion and onset of symptoms, severe coagulopathy

Coagulopathy

Coagulopathy is a condition in which the blood’s ability to clot is impaired. This condition can cause prolonged or excessive bleeding, which may occur spontaneously or following an injury or medical and dental procedures.The normal clotting process depends on the interplay of various proteins in...

(blood clotting disorder), severe hyperbilirubinemia (jaundice), and rising serum creatinine

Creatinine

Creatinine is a break-down product of creatine phosphate in muscle, and is usually produced at a fairly constant rate by the body...

levels.

Similar species

The color and general appearance of A. bisporigera are similar to those of A. vernaAmanita verna

Amanita verna, commonly known as the fool's mushroom, Destroying angel or the mushroom fool, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in Europe in spring, A. verna associates with various deciduous and coniferous trees...

and A. virosa

Amanita virosa

Amanita virosa, commonly known as the European destroying angel, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in Europe, A. virosa associates with various deciduous and coniferous trees...

. A. bisporigera is at times smaller and more slender than either A. verna or A. virosa, but it varies considerably in size; therefore size is not a reliable diagnostic characteristic. A. virosa fruits in autumn—later than A. bisporigera. A. elliptosperma

Amanita elliptosperma

Amanita elliptosperma, commonly known as the Atkinson's destroying angel, is a basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Although its toxicity is unknown, it is likely to be deadly poisonous like its close relatives...

is less common but widely distributed in the southeastern United States, while A. ocreata

Amanita ocreata

Amanita ocreata, commonly known as the death angel, destroying angel, angel of death or more precisely Western North American destroying angel, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in the Pacific Northwest and California floristic provinces of...

is found on the West Coast

West Coast of the United States

West Coast or Pacific Coast are terms for the westernmost coastal states of the United States. The term most often refers to the states of California, Oregon, and Washington. Although not part of the contiguous United States, Alaska and Hawaii do border the Pacific Ocean but can't be included in...

and in the Southwest. Other similar toxic North American species include Amanita magnivelaris

Amanita magnivelaris

Amanita magnivelaris, commonly known as the great felt skirt destroying angel, is a poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Originally described from Ithaca, New York, by Charles Horton Peck, it is found in New York state and southeastern Canada.-See also:*List of Amanita...

, which has a cream-colored, rather thick, felted-submembranous, skirt-like ring, and A. virosiformis

Amanita virosiformis

Amanita virosiformis, commonly known as the narrow-spored destroying angel, is a poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Originally described from Florida, is found from coastal North Carolina through to eastern Texas in the southeastern United States.-See also:*List of...

, which has elongated spores that are 3.9–4.7 by 11.7–13.4 μm. Neither A. elliptosperma nor A. magnivelaris typically turn yellow with the application of KOH; the KOH reaction of A. virosiformis has not been reported.

Leucoagaricus leucothites is another all-white mushroom with an annulus, free gills, and white spore print, but it lacks a volva and has thick-walled dextrinoid (staining red-brown in Melzer's reagent

Melzer's Reagent

Melzer's reagent is a chemical reagent used by mycologists to assist with the identification of fungi.-Composition:...

) egg-shaped spores with a pore. A. bisporigera may also be confused with the larger edible

Edible mushroom

Edible mushrooms are the fleshy and edible fruiting bodies of several species of fungi. Mushrooms belong to the macrofungi, because their fruiting structures are large enough to be seen with the naked eye. They can appear either below ground or above ground where they may be picked by hand...

species Agaricus silvicola

Agaricus silvicola

Agaricus silvicola, also known as the Wood Mushroom is a species of Agaricus mushroom related to the button mushroom.- Description :...

, the "horse-mushroom". Like many white amanitas, young fruit bodies of A. bisporigera, still enveloped in the universal veil, can be confused with puffball

Puffball

A puffball is a member of any of several groups of fungus in the division Basidiomycota. The puffballs were previously treated as a taxonomic group called the Gasteromycetes or Gasteromycetidae, but they are now known to be a polyphyletic assemblage. The distinguishing feature of all puffballs is...

species, but a longitudinal cut of the fruit body reveals internal structures in the Amanita that are absent in puffballs. In 2006, seven members of the Hmong

Hmong people

The Hmong , are an Asian ethnic group from the mountainous regions of China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. Hmong are also one of the sub-groups of the Miao ethnicity in southern China...

community living in Minnesota were poisoned with A. bisporigera because they had confused it with edible paddy straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea

Volvariella volvacea

Volvariella volvacea is a species of edible mushroom cultivated throughout East and Southeast Asia and used extensively in Asian cuisines. In Chinese, they are called cǎogū Volvariella volvacea (also known as straw mushroom or paddy straw mushroom; syn. Volvaria volvacea, Agaricus volvaceus,...

) that grow in Southeast Asia.

Habitat and distribution

Like most other Amanita species, A. bisporigera is thought to form mycorrhizal relationships with trees. This is a mutually beneficial relationship where the hyphae of the fungus grow around the roots of trees, enabling the fungus to receive moisture, protection and nutritive byproducts of the tree, and giving the tree greater access to soil nutrients. Fruit bodies of Amanita bisporigera are found on the ground growing solitarily, scattered, or in groups in mixedTemperate broadleaf and mixed forests

Mixed forests are a temperate and humid biome. The typical structure of these forests includes four layers. The uppermost layer is the canopy composed of tall mature trees ranging from 33 to 66 m high. Below the canopy is the three-layered, shade-tolerant understory that is roughly 9 to...

coniferous and deciduous forests; they tend to appear during summer and early fall. The fruit bodies are commonly found near oak

Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus Quercus , of which about 600 species exist. "Oak" may also appear in the names of species in related genera, notably Lithocarpus...

, but have been reported in birch

Birch

Birch is a tree or shrub of the genus Betula , in the family Betulaceae, closely related to the beech/oak family, Fagaceae. The Betula genus contains 30–60 known taxa...

-aspen

Aspen

Populus section Populus, of the Populus genus, includes the aspen trees and the white poplar Populus alba. The five typical aspens are all native to cold regions with cool summers, in the north of the Northern Hemisphere, extending south at high altitudes in the mountains. The White Poplar, by...

areas in the west. It is most commonly found in eastern North America, and in rare is western North America. It is widely distributed in Canada, and the distribution extends south to Mexico. The species has been found in Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

, where it may have been exported in pine plantation

Plantation

A plantation is a long artificially established forest, farm or estate, where crops are grown for sale, often in distant markets rather than for local on-site consumption...

s.

Genome sequencing

The Amanita Genome Project was begun in Jonathan Walton's lab at Michigan State UniversityMichigan State University

Michigan State University is a public research university in East Lansing, Michigan, USA. Founded in 1855, it was the pioneer land-grant institution and served as a model for future land-grant colleges in the United States under the 1862 Morrill Act.MSU pioneered the studies of packaging,...

in 2004 as part of their ongoing studies of Amanita bisporigera. The purpose of the project is to determine the gene

Gene

A gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

s and genetic controls associated with the formation of mycorrhizae, and to elucidate the biochemical mechanisms of toxin production. The genome

Genome

In modern molecular biology and genetics, the genome is the entirety of an organism's hereditary information. It is encoded either in DNA or, for many types of virus, in RNA. The genome includes both the genes and the non-coding sequences of the DNA/RNA....

of A. bisporigera has been sequenced using a combination of automated Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing

Pyrosequencing

Pyrosequencing is a method of DNA sequencing based on the "sequencing by synthesis" principle. It differs from Sanger sequencing, in that it relies on the detection of pyrophosphate release on nucleotide incorporation, rather than chain termination with dideoxynucleotides...

, and the genome sequence information is publicly searchable. The sequence data enabled the researchers to identify the genes responsible for amatoxin and phallotoxin biosynthesis, AMA1 and PHA1. The cyclic peptides are synthesized on ribosomes, and require proline

Proline

Proline is an α-amino acid, one of the twenty DNA-encoded amino acids. Its codons are CCU, CCC, CCA, and CCG. It is not an essential amino acid, which means that the human body can synthesize it. It is unique among the 20 protein-forming amino acids in that the α-amino group is secondary...

-specific peptidases from the prolyl oligopeptidase family for processing

Posttranslational modification

Posttranslational modification is the chemical modification of a protein after its translation. It is one of the later steps in protein biosynthesis, and thus gene expression, for many proteins....

.

The genetic sequence information from A. bisporigera has been used to identify molecular polymorphisms

Polymorphism (biology)

Polymorphism in biology occurs when two or more clearly different phenotypes exist in the same population of a species — in other words, the occurrence of more than one form or morph...

in the related A. phalloides. These single-nucleotide polymorphisms may be used as population genetic marker

Genetic marker

A genetic marker is a gene or DNA sequence with a known location on a chromosome that can be used to identify cells, individuals or species. It can be described as a variation that can be observed...

s to study phylogeography

Phylogeography

Phylogeography is the study of the historical processes that may be responsible for the contemporary geographic distributions of individuals. This is accomplished by considering the geographic distribution of individuals in light of the patterns associated with a gene genealogy.This term was...

and population genetics

Population genetics

Population genetics is the study of allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the four main evolutionary processes: natural selection, genetic drift, mutation and gene flow. It also takes into account the factors of recombination, population subdivision and population...

. Sequence information has also been employed to show that A. bisporigera lacks many of the major classes of secreted enzymes that break down the complex polysaccharide

Polysaccharide

Polysaccharides are long carbohydrate molecules, of repeated monomer units joined together by glycosidic bonds. They range in structure from linear to highly branched. Polysaccharides are often quite heterogeneous, containing slight modifications of the repeating unit. Depending on the structure,...

s of plant cell walls, like cellulose

Cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to over ten thousand β linked D-glucose units....

. In contrast, saprobic fungi like Coprinopsis cinerea

Coprinopsis cinerea

Coprinopsis cinerea is a species of mushroom in the Psathyrellaceae family. Commonly known as the gray shag, it is edible, but must be used promptly after collecting....

and Galerina marginata

Galerina marginata

Galerina marginata is a species of poisonous fungus in the family Hymenogastraceae of the order Agaricales. Prior to 2001, the species G. autumnalis, G. oregonensis, G. unicolor, and G. venenata were thought to be separate due to differences in habitat and the viscidity of their...

, which break down organic matter

Organic matter

Organic matter is matter that has come from a once-living organism; is capable of decay, or the product of decay; or is composed of organic compounds...

to obtain nutrients, have a more complete complement of cell wall-degrading enzymes. Although few ectomycorrhizal fungi have yet been tested in this way, the authors suggest that the absence of plant cell wall-degrading ability may correlate with the ectomycorrhizal ecological niche.