Alfred Deakin

Encyclopedia

Alfred Deakin Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia

. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal

reforms in the colony of Victoria

, including the protection of rights at work. He also played a major part in establishing irrigation in Australia

. It is likely that he could have been Premier

of Victoria, but he chose to devote his energy to federation.

Throughout the 1890s Deakin was a participant in conferences of representatives of the Australian colonies that were established to draft a constitution for the proposed federation

. He played an important role in ensuring that the draft was liberal and democratic and in achieving compromises to enable its eventual success. Between conferences, he worked to popularise the concept of federation and campaigned for its acceptance in colonial referenda. He then fought hard to ensure acceptance of the proposed constitution by the Government of the United Kingdom.

As Prime Minister, Deakin completed a vast legislative program that makes him, with Labor

's Andrew Fisher

, the founder of an effective Commonwealth government

. He expanded the High Court

, provided major funding for the purchase of ships—leading to the establishment of the Royal Australian Navy

as a significant force under the Fisher

government—and established Australian control of Papua. Confronted by the rising Australian Labor Party

in 1909, he merged his Protectionist Party

with Joseph Cook

's Anti-Socialist Party

to create the Commonwealth Liberal Party

(known commonly as the Fusion), the main ancestor of the modern Liberal Party of Australia

. The Deakin-led Liberal Party government lost to Fisher Labor at the 1910 election

, which saw the first time a federal political party had been elected with a majority in either house in Federal Parliament. Deakin resigned from Parliament prior to the 1913 election

, with Joseph Cook

winning the Liberal Party leadership ballot.

Deakin was the second child of English immigrants, William Deakin and his wife Sarah Bill, daughter of a Shropshire

Deakin was the second child of English immigrants, William Deakin and his wife Sarah Bill, daughter of a Shropshire

farmer, who had migrated to Australia in 1850 and settled in the Melbourne suburb of Collingwood

in 1853. Deakin worked as a storekeeper, water-carter and general carrier and then became a partner in a coaching business and later manager of Cobb and Co

in Victoria.

Deakin was born at 90 George Street, Fitzroy

, Melbourne, and began his education at the age of four in a boarding school that was initially located at Kyneton

, but later moved to the Melbourne suburb of South Yarra

. In 1864 he became a day pupil at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School, but did not study seriously until his later school years, when he came under the influence of J. H. Thompson and the school's headmaster, John Edward Bromby

, whose oratorical style Deakin admired and later partly adopted. In 1871 he matriculated with good passes in history, algebra

and Euclid

and basic passes in English and Latin

. He began evening classes in law at the University of Melbourne

, while working as a schoolteacher and private tutor. He also spoke frequently at the University Debating Club founded by Charles Henry Pearson

in 1874, read widely, dabbled in writing and became a lifelong spiritualist, holding the office of President of the Victorian Spiritualists' Union.

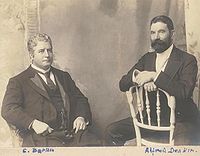

Deakin graduated in 1877 and began practising as a barrister

, but had difficulty in obtaining briefs. In May 1878, he met David Syme

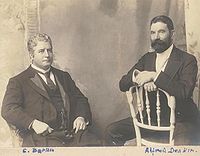

, the owner of the Melbourne daily The Age

, who paid him to contribute reviews, leaders and articles on politics and literature. In 1880, he became editor of The Leader, The Age's weekly. During this period Syme converted him from supporting free trade to protectionism. He became active in the Australian Natives Association

and began to practise vegetarianism.

Deakin stood for the largely rural seat of West Bourke in the Victorian Legislative Assembly

Deakin stood for the largely rural seat of West Bourke in the Victorian Legislative Assembly

in February 1879, as a supporter of Legislative Council

reform, protection to encourage manufacturing and the introduction of a land tax to break up the big agricultural estates, and won by 79 votes. Due to a number of voters being disenfranchised by a shortage of voting papers, he resigned and lost the subsequent by-election by 15 votes, narrowly lost the seat in the February 1880 general election, but won it in yet another early general election in July 1880. The radical Premier, Graham Berry

, offered him the position of Attorney-General in August, but Deakin turned him down.

In 1882, Deakin married Elizabeth Martha Anne ("Pattie") Browne, daughter of a well-known spiritualist. They lived with Deakin's parents until 1887, when they moved to "Llanarth", in Walsh Street, South Yarra. They had three daughters, Ivy, Stella and Vera by 1891.

In 1883 Deakin became Commissioner for Public Works and Water Supply, and in 1884 he became Solicitor-General and Minister of Public Works. In 1885 Deakin secured the passage of the colony's pioneering Factories and Shops Act, enforcing regulation of employment conditions and hours of work. In December 1884 he went to the United States to investigate irrigation, and presented a report in June 1885, Irrigation in Western America. Percival Serle

In 1883 Deakin became Commissioner for Public Works and Water Supply, and in 1884 he became Solicitor-General and Minister of Public Works. In 1885 Deakin secured the passage of the colony's pioneering Factories and Shops Act, enforcing regulation of employment conditions and hours of work. In December 1884 he went to the United States to investigate irrigation, and presented a report in June 1885, Irrigation in Western America. Percival Serle

described this report as "... a remarkable piece of accurate observation, and was immediately reprinted by the United States government". In June 1886, he introduced legislation to nationalise water rights and provide state-aid for irrigation works that helped establish irrigation in Australia

.

In 1885, Deakin became Chief Secretary and Commissioner for Water Supply and from 1890 Minister for Health and, briefly, Solicitor-General. In 1887 he led Victoria's delegation to the Imperial Conference in London, where he argued forcibly for reduced colonial payments for the defence provided by the British Navy

and for improved consultation in relation to the New Hebrides

. In 1889, he became the member for the Melbourne seat of Essendon and Flemington

.

In 1890 the government was brought down over its use of the militia to protect non-union labour during the maritime strike

. In addition, Deakin lost his fortune and his father's fortune in the property crash of 1893, and had to return to the bar to restore his finances. In 1892, he unsuccessfully defended the mass murderer Frederick Bailey Deeming

and assisted the defence in the 1893–94 libel trial of David Syme

.

in Melbourne in 1890, which agreed to hold an intercolonial convention to draft a federal constitution. He was a leading negotiator at the Federal Conventions of 1891, which produced a draft constitution that contained much of the Constitution of Australia

, as finally enacted in 1900. Deakin was also a delegate to the second Australasian Federal Convention, which opened in Adelaide in March 1897 and concluded in Melbourne in January 1898. He opposed conservative plans for the indirect election of senators, attempted to weaken the powers of the Senate

—and in particular sought to prevent it from being able to defeat money bills—and supported wide taxation powers for the federal government. Deakin often had to reconcile differences and find ways out of apparently impossible difficulties. Between and after these meetings, he travelled through the country addressing public meetings and he was partly responsible for the large majority in Victoria at each referendum.

In 1900 Deakin travelled to London with Edmund Barton

and Charles Kingston

to oversee the passage of the federation bill through the Imperial Parliament, and took part in the negotiations with Joseph Chamberlain

, the Colonial Secretary, who insisted on the right of appeal from the High Court

to the Privy Council

. Eventually a compromise was reached, under which constitutional (inter se

) matters could be finalised in the High Court, but other matters could be appealed to the Privy Council.

Deakin defined himself as an "independent Australian Briton," favouring a self-governing Australia but loyal to the British Empire

. He certainly did not see federation as marking Australia's independence from Britain. On the contrary, Deakin was a supporter of closer empire unity, serving as president of the Victorian branch of the Imperial Federation

League, a cause he believed to be a stepping stone to a more spiritual world unity.

In 1901 Deakin was elected to the first federal Parliament as MP for Ballaarat

In 1901 Deakin was elected to the first federal Parliament as MP for Ballaarat

, and became Attorney-General

in the ministry headed by Edmund Barton

. He was active, especially in drafting bills for the Public Service, arbitration and the High Court. His second reading speech on the Immigration Restriction Bill to implement the White Australia Policy

was notable in avoiding blatant racism by arguing that it was necessary to exclude the Japanese because of their good qualities, which would place them at an advantage over European Australians. His March 1902 speech in favour of the bill establishing the High Court of Australia

, helped overcome significant opposition to its establishment.

did not have a majority in either House, and he held office only by courtesy of the Labor Party

, which insisted on legislation more radical than Deakin was willing to accept. In April 1904 he resigned without having passed any legislation. The Labor leader Chris Watson

and the Free Trade

leader George Reid

succeeded him, but neither could form a stable ministry.

was established in 1906, Bureau of Meteorology was established in 1908 and the Quarantine Act was passed in 1908.

In 1906 Deakin's government amended the Judiciary Act to increase the size of the High Court

to five judges, as envisaged in the constitution, and appointed Isaac Isaacs

and H. B. Higgins

to fill the two additional seats. The first protective Federal tariff, the Australian Industries Protection Act was passed. This "New Protection" measure attempted to force companies to pay fair wages by setting conditions for tariff protection, although the Commonwealth had no powers over wages and prices.

The Papua Act of 1905 established an Australian administration for the former British New Guinea and Deakin appointed Hubert Murray

as Lieutenant-Governor of Papua in 1908, who ruled it for a 32-year period as a benevolent paternalist. His government passed a bill for the transfer of control of the Northern Territory

from South Australia to the Commonwealth, which became effective in 1911.

In December 1907, he introduced the first bill to establish compulsory military service, which was also strongly supported by Labor's Watson and Billy Hughes

. He had long opposed the naval agreements to fund Royal Navy protection of Australia although Barton had agreed in 1902 that the Commonwealth would take over such funding from the colonies. In 1906 he announced that Australia would purchase destroyers, and in 1907 travelled to an Imperial Conference in London to discuss the issue, without success. In 1908 he invited Theodore Roosevelt

's Great White Fleet

to visit Australia, in a symbolic act of independence from Britain. The Surplus Revenue Act of 1908 provided £250,000 for naval expenditure, although these funds were first applied by the Andrew Fisher

Labor government, creating the first independent navy

in the British empire.

", with his old conservative

opponent George Reid

, and returned to power in May 1909 at the head of Australia's first majority government. The Fusion was seen by many as a betrayal of Deakin's liberal principles, and he was called a "Judas" by Sir William Lyne

. He ordered the dreadnought

battle cruiser, Australia

and established the financial agreement of 1909, which gave the States annual grants of 25 shillings ($2.50) per person, which was the basis of Commonwealth-state financial arrangements until 1927. In the April 1910 election

his party was soundly defeated by Labor under Andrew Fisher

.

held in San Francisco to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal

, but found his duties difficult because of severe progressive memory loss (possibly due to early-onset Alzheimer's disease

). He became an invalid and died in 1919 of meningoencephalitis

aged only 63. He is buried in the St. Kilda Cemetery, alongside his wife.

and destiny

working in his career. Like Dag Hammarskjöld

much later, Deakin's sincere longing for spiritual fulfillment led him to express a sense of unworthiness in his private diaries which mingled with his literary aspirations as a poet.

His private prayer diaries, like those of Samuel Johnson

, express a profound contemplative (though more ecumenical) Christian view of the importance of humility

in seeking divine assistance with his career. "A life, the life of Christ," Deakin wrote, "that is the one thing needful—the only revelation required is there ... We have but to live it." In 1888, as an example relevant to his work for Federation, Deakin prayed: "Oh God, grant me that judgment & forsight which will enable me to serve my country—guide me and strengthen me, so that I may follow & persuade others to follow the path which shall lead to the elevation of national life & thought & permanence of well earned prosperity—give me light & truth & influence for the highest & the highest only." As Walter Murdoch pointed out, "[Deakin] believed himself to be inspired, and to have a divine message and mission."

Historian Manning Clark

, whose History of Australia cites extensively from his studies of Deakin's private diaries in the National Library of Australia

, wrote: "By reading the world's scriptures and mystics

a deep peace had settled far inside [Deakin]: now he felt a 'serenity at the core of my heart.' He wanted to know whether participation in the world's affairs would disturb that serenity ... he was tormented by the thought that the emptiness of the man within corresponded with the emptiness of society at large where Mammon

had found a new demesne to infest."

Deakin was almost universally liked, admired and respected by his contemporaries, who called him "Affable Alfred." He made his only real enemies at the time of the Fusion, when not only Labor but some liberals such as Sir William Lyne

Deakin was almost universally liked, admired and respected by his contemporaries, who called him "Affable Alfred." He made his only real enemies at the time of the Fusion, when not only Labor but some liberals such as Sir William Lyne

reviled him as a traitor.

He had a long and happy marriage and was survived by his wife and their three daughters:

His descendants are still active in Melbourne political and business circles (notably his great-grandson Tom Harley), and he is regarded as a founding father by the modern Liberal Party

. The Division of Deakin

, Alfred Deakin High School

, Deakin University

, Deakin Avenue in the rural city of Mildura, Deakin House at Melbourne Grammar School

and the Canberra

suburb of Deakin

are named after him.

In 1969, Australia Post

honoured him on a postage stamp

bearing his portrait.

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

reforms in the colony of Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

, including the protection of rights at work. He also played a major part in establishing irrigation in Australia

Irrigation in Australia

Irrigation in Australia is a widespread practice to supplement low rainfall levels in Australia with water from other sources to assist in the production of crops or pasture. As the driest inhabited continent, irrigation is required in many areas for production of crops for domestic and export use...

. It is likely that he could have been Premier

Premiers of Victoria

The Premier of Victoria is the leader of the government in the Australian state of Victoria. The Premier is appointed by the Governor of Victoria, and is the leader of the political party able to secure a majority in the Legislative Assembly....

of Victoria, but he chose to devote his energy to federation.

Throughout the 1890s Deakin was a participant in conferences of representatives of the Australian colonies that were established to draft a constitution for the proposed federation

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is the supreme law under which the Australian Commonwealth Government operates. It consists of several documents. The most important is the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia...

. He played an important role in ensuring that the draft was liberal and democratic and in achieving compromises to enable its eventual success. Between conferences, he worked to popularise the concept of federation and campaigned for its acceptance in colonial referenda. He then fought hard to ensure acceptance of the proposed constitution by the Government of the United Kingdom.

As Prime Minister, Deakin completed a vast legislative program that makes him, with Labor

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

's Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher was an Australian politician who served as the fifth Prime Minister on three separate occasions. Fisher's 1910-13 Labor ministry completed a vast legislative programme which made him, along with Protectionist Alfred Deakin, the founder of the statutory structure of the new nation...

, the founder of an effective Commonwealth government

Government of Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia is a federal constitutional monarchy under a parliamentary democracy. The Commonwealth of Australia was formed in 1901 as a result of an agreement among six self-governing British colonies, which became the six states...

. He expanded the High Court

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

, provided major funding for the purchase of ships—leading to the establishment of the Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy is the naval branch of the Australian Defence Force. Following the Federation of Australia in 1901, the ships and resources of the separate colonial navies were integrated into a national force: the Commonwealth Naval Forces...

as a significant force under the Fisher

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher was an Australian politician who served as the fifth Prime Minister on three separate occasions. Fisher's 1910-13 Labor ministry completed a vast legislative programme which made him, along with Protectionist Alfred Deakin, the founder of the statutory structure of the new nation...

government—and established Australian control of Papua. Confronted by the rising Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

in 1909, he merged his Protectionist Party

Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

with Joseph Cook

Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook, GCMG was an Australian politician and the sixth Prime Minister of Australia. Born as Joseph Cooke and working in the coal mines of Silverdale, Staffordshire during his early life, he emigrated to Lithgow, New South Wales during the late 1880s, and became General-Secretary of the...

's Anti-Socialist Party

Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states and renamed the Anti-Socialist Party in 1906, was an Australian political party, formally organised between 1889 and 1909...

to create the Commonwealth Liberal Party

Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Commonwealth Liberal Party was a political movement active in Australia from 1909 to 1916, shortly after federation....

(known commonly as the Fusion), the main ancestor of the modern Liberal Party of Australia

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Founded a year after the 1943 federal election to replace the United Australia Party, the centre-right Liberal Party typically competes with the centre-left Australian Labor Party for political office...

. The Deakin-led Liberal Party government lost to Fisher Labor at the 1910 election

Australian federal election, 1910

Federal elections were held in Australia on 13 April 1910. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

, which saw the first time a federal political party had been elected with a majority in either house in Federal Parliament. Deakin resigned from Parliament prior to the 1913 election

Australian federal election, 1913

Federal elections were held in Australia on 31 May 1913. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Australian Labor Party led by Prime Minister of Australia Andrew Fisher was defeated by the opposition Commonwealth Liberal...

, with Joseph Cook

Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook, GCMG was an Australian politician and the sixth Prime Minister of Australia. Born as Joseph Cooke and working in the coal mines of Silverdale, Staffordshire during his early life, he emigrated to Lithgow, New South Wales during the late 1880s, and became General-Secretary of the...

winning the Liberal Party leadership ballot.

Early life

Shropshire

Shropshire is a county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. It borders Wales to the west...

farmer, who had migrated to Australia in 1850 and settled in the Melbourne suburb of Collingwood

Collingwood, Victoria

Collingwood is an inner city suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 3 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Yarra...

in 1853. Deakin worked as a storekeeper, water-carter and general carrier and then became a partner in a coaching business and later manager of Cobb and Co

Cobb and Co

Cobb and Co is the name of a transportation company in Australia. It was prominent in the late 19th century when it operated stagecoaches to many areas in the outback and at one point in several other countries, as well....

in Victoria.

Deakin was born at 90 George Street, Fitzroy

Fitzroy, Victoria

Fitzroy is an inner city suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Yarra. Its borders are Alexandra Parade , Victoria Parade , Smith Street and Nicholson Street. Fitzroy is Melbourne's...

, Melbourne, and began his education at the age of four in a boarding school that was initially located at Kyneton

Kyneton, Victoria

Kyneton is a town on the Calder Highway in the Macedon Ranges of Victoria, Australia. The Calder Freeway bypasses Kyneton to the north and east. The town was named after the English village of Kineton, Warwickshire. The town has three main streets: Mollison Street, Piper Street and High Street...

, but later moved to the Melbourne suburb of South Yarra

South Yarra, Victoria

South Yarra is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 4 km south-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area are the Cities of Stonnington and Melbourne...

. In 1864 he became a day pupil at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School, but did not study seriously until his later school years, when he came under the influence of J. H. Thompson and the school's headmaster, John Edward Bromby

John Edward Bromby

John Edward Bromby was an Australian schoolmaster and Anglican cleric.Bromby was born in Hull, England, the son of the Reverend John Healey Bromby and his wife Jane, née Amis. His brother was Charles Henry Bromby, later Bishop of Tasmania. Bromby was educated at Hull Grammar School, Uppingham...

, whose oratorical style Deakin admired and later partly adopted. In 1871 he matriculated with good passes in history, algebra

Algebra

Algebra is the branch of mathematics concerning the study of the rules of operations and relations, and the constructions and concepts arising from them, including terms, polynomials, equations and algebraic structures...

and Euclid

Euclid

Euclid , fl. 300 BC, also known as Euclid of Alexandria, was a Greek mathematician, often referred to as the "Father of Geometry". He was active in Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy I...

and basic passes in English and Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

. He began evening classes in law at the University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

, while working as a schoolteacher and private tutor. He also spoke frequently at the University Debating Club founded by Charles Henry Pearson

Charles Henry Pearson

Charles Henry Pearson was a British-born Australian historian, educationist, politician and journalist. According to John Tregenza, "Pearson was the outstanding intellectual of the Australian colonies...

in 1874, read widely, dabbled in writing and became a lifelong spiritualist, holding the office of President of the Victorian Spiritualists' Union.

Deakin graduated in 1877 and began practising as a barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

, but had difficulty in obtaining briefs. In May 1878, he met David Syme

David Syme

David Syme was a Scottish-Australian newspaper proprietor of The Age and regarded as "the father of protection in Australia" who had immense influence in the Government of Victoria.-Early life and family:...

, the owner of the Melbourne daily The Age

The Age

The Age is a daily broadsheet newspaper, which has been published in Melbourne, Australia since 1854. Owned and published by Fairfax Media, The Age primarily serves Victoria, but is also available for purchase in Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and border regions of South Australia and...

, who paid him to contribute reviews, leaders and articles on politics and literature. In 1880, he became editor of The Leader, The Age's weekly. During this period Syme converted him from supporting free trade to protectionism. He became active in the Australian Natives Association

Australian Natives Association

The Australian Natives' Association , a mutual society was founded in Melbourne, Australia in April 1871. The Association played a leading role in the movement for Australian federation in the last 20 years of the 19th century. In 1900 it had a membership of 17,000, mainly in Victoria.The ANA...

and began to practise vegetarianism.

Victorian politics

Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the Parliament of Victoria in Australia. Together with the Victorian Legislative Council, the upper house, it sits in Parliament House in the state capital, Melbourne.-History:...

in February 1879, as a supporter of Legislative Council

Victorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council, is the upper of the two houses of the Parliament of Victoria, Australia; the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit in Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative Council serves as a house of review, in a similar fashion to...

reform, protection to encourage manufacturing and the introduction of a land tax to break up the big agricultural estates, and won by 79 votes. Due to a number of voters being disenfranchised by a shortage of voting papers, he resigned and lost the subsequent by-election by 15 votes, narrowly lost the seat in the February 1880 general election, but won it in yet another early general election in July 1880. The radical Premier, Graham Berry

Graham Berry

Sir Graham Berry KCMG , Australian colonial politician, was the 11th Premier of Victoria. He was one of the most Radical and colourful figures in the politics of colonial Victoria, and made the most determined efforts to break the power of the Victorian Legislative Council, the stronghold of the...

, offered him the position of Attorney-General in August, but Deakin turned him down.

In 1882, Deakin married Elizabeth Martha Anne ("Pattie") Browne, daughter of a well-known spiritualist. They lived with Deakin's parents until 1887, when they moved to "Llanarth", in Walsh Street, South Yarra. They had three daughters, Ivy, Stella and Vera by 1891.

Percival Serle

Percival Serle was an Australian biographer and bibliographer.Serle was born in Victoria and for many years worked in a life assurance office before becoming chief clerk and accountant at the University of Melbourne...

described this report as "... a remarkable piece of accurate observation, and was immediately reprinted by the United States government". In June 1886, he introduced legislation to nationalise water rights and provide state-aid for irrigation works that helped establish irrigation in Australia

Irrigation in Australia

Irrigation in Australia is a widespread practice to supplement low rainfall levels in Australia with water from other sources to assist in the production of crops or pasture. As the driest inhabited continent, irrigation is required in many areas for production of crops for domestic and export use...

.

In 1885, Deakin became Chief Secretary and Commissioner for Water Supply and from 1890 Minister for Health and, briefly, Solicitor-General. In 1887 he led Victoria's delegation to the Imperial Conference in London, where he argued forcibly for reduced colonial payments for the defence provided by the British Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

and for improved consultation in relation to the New Hebrides

New Hebrides

New Hebrides was the colonial name for an island group in the South Pacific that now forms the nation of Vanuatu. The New Hebrides were colonized by both the British and French in the 18th century shortly after Captain James Cook visited the islands...

. In 1889, he became the member for the Melbourne seat of Essendon and Flemington

Electoral district of Essendon and Flemington

Essendon and Flemington was an electoral district of the Victorian Legislative Assembly from 1889 to 1904. It was held for most of its existence by future Prime Minister Alfred Deakin before his switch to federal politics in 1901. It was abolished in 1904 and replaced with separate Essendon and...

.

In 1890 the government was brought down over its use of the militia to protect non-union labour during the maritime strike

1890 Australian maritime dispute

The 1890 Australian Maritime Dispute, commonly known as the 1890 Maritime Strike, was on a scale unprecedented in the Australian colonies to that point in time, causing political and social turmoil across all Australian colonies and in New Zealand, including the collapse of colonial governments in...

. In addition, Deakin lost his fortune and his father's fortune in the property crash of 1893, and had to return to the bar to restore his finances. In 1892, he unsuccessfully defended the mass murderer Frederick Bailey Deeming

Frederick Bailey Deeming

Frederick Bailey Deeming was an English-born Australian gasfitter and murderer.Deeming was born in Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire, England, son of Thomas Deeming, brazier, and his wife Ann, née Bailey. He was a "difficult child" according to writers Maurice Gurvich and Christopher Wray...

and assisted the defence in the 1893–94 libel trial of David Syme

David Syme

David Syme was a Scottish-Australian newspaper proprietor of The Age and regarded as "the father of protection in Australia" who had immense influence in the Government of Victoria.-Early life and family:...

.

The road to Federation

After 1890, Deakin refused all offers of cabinet posts and devoted his attention to the movement for federation. He was Victoria's delegate to the Australasian Federal Conference, convened by Sir Henry ParkesHenry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, GCMG was an Australian statesman, the "Father of Federation." As the earliest advocate of a Federal Council of the colonies of Australia, a precursor to the Federation of Australia, he was the most prominent of the Australian Founding Fathers.Parkes was described during his...

in Melbourne in 1890, which agreed to hold an intercolonial convention to draft a federal constitution. He was a leading negotiator at the Federal Conventions of 1891, which produced a draft constitution that contained much of the Constitution of Australia

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is the supreme law under which the Australian Commonwealth Government operates. It consists of several documents. The most important is the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia...

, as finally enacted in 1900. Deakin was also a delegate to the second Australasian Federal Convention, which opened in Adelaide in March 1897 and concluded in Melbourne in January 1898. He opposed conservative plans for the indirect election of senators, attempted to weaken the powers of the Senate

Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives. Senators are popularly elected under a system of proportional representation. Senators are elected for a term that is usually six years; after a double dissolution, however,...

—and in particular sought to prevent it from being able to defeat money bills—and supported wide taxation powers for the federal government. Deakin often had to reconcile differences and find ways out of apparently impossible difficulties. Between and after these meetings, he travelled through the country addressing public meetings and he was partly responsible for the large majority in Victoria at each referendum.

In 1900 Deakin travelled to London with Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

and Charles Kingston

Charles Kingston

Charles Cameron Kingston, Australian politician, was an early liberal Premier of South Australia serving from 1893 to 1899 with the support of Labor led by John McPherson from 1893 and Lee Batchelor from 1897 in the House of Assembly, winning the 1893, 1896, and 1899 state elections against the...

to oversee the passage of the federation bill through the Imperial Parliament, and took part in the negotiations with Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain was an influential British politician and statesman. Unlike most major politicians of the time, he was a self-made businessman and had not attended Oxford or Cambridge University....

, the Colonial Secretary, who insisted on the right of appeal from the High Court

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

to the Privy Council

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council is one of the highest courts in the United Kingdom. Established by the Judicial Committee Act 1833 to hear appeals formerly heard by the King in Council The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is one of the highest courts in the United...

. Eventually a compromise was reached, under which constitutional (inter se

Inter se

Inter se is a Legal Latin phrase meaning "between or amongst themselves". For example;In Australian constitutional law, it refers to matters concerning a dispute between the Commonwealth and one or more of the States concerning the extents of their respective powers....

) matters could be finalised in the High Court, but other matters could be appealed to the Privy Council.

Deakin defined himself as an "independent Australian Briton," favouring a self-governing Australia but loyal to the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. He certainly did not see federation as marking Australia's independence from Britain. On the contrary, Deakin was a supporter of closer empire unity, serving as president of the Victorian branch of the Imperial Federation

Imperial Federation

Imperial Federation was a late-19th early-20th century proposal to create a federated union in place of the existing British Empire.-Motivators:...

League, a cause he believed to be a stepping stone to a more spiritual world unity.

Federal politics

Division of Ballarat

The Division of Ballarat is an Australian Electoral Division in Victoria. The division was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It is named for the provincial city of Ballarat....

, and became Attorney-General

Attorney-General of Australia

The Attorney-General of Australia is the first law officer of the Crown, chief law officer of the Commonwealth of Australia and a minister of the Crown. The Attorney-General is usually a member of the Federal Cabinet, but there is no constitutional requirement that this be the case since the...

in the ministry headed by Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

. He was active, especially in drafting bills for the Public Service, arbitration and the High Court. His second reading speech on the Immigration Restriction Bill to implement the White Australia Policy

White Australia policy

The White Australia policy comprises various historical policies that intentionally restricted "non-white" immigration to Australia. From origins at Federation in 1901, the polices were progressively dismantled between 1949-1973....

was notable in avoiding blatant racism by arguing that it was necessary to exclude the Japanese because of their good qualities, which would place them at an advantage over European Australians. His March 1902 speech in favour of the bill establishing the High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

, helped overcome significant opposition to its establishment.

First government 1903–04

When Barton retired to become one of the founding justices of the High Court, Deakin succeeded him as Prime Minister on 24 September 1903. His Protectionist PartyProtectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

did not have a majority in either House, and he held office only by courtesy of the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

, which insisted on legislation more radical than Deakin was willing to accept. In April 1904 he resigned without having passed any legislation. The Labor leader Chris Watson

Chris Watson

John Christian Watson , commonly known as Chris Watson, Australian politician, was the third Prime Minister of Australia...

and the Free Trade

Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states and renamed the Anti-Socialist Party in 1906, was an Australian political party, formally organised between 1889 and 1909...

leader George Reid

George Reid (Australian politician)

Sir George Houstoun Reid, GCB, GCMG, KC was an Australian politician, Premier of New South Wales and the fourth Prime Minister of Australia....

succeeded him, but neither could form a stable ministry.

Second government 1905–08

Deakin resumed office in mid-1905, and retained it for three years. During this, the longest and most successful of his terms as Prime Minister, his government was responsible for much policy and legislation giving shape to the Commonwealth during its first decade, including bills to create an Australian currency. The Copyright Act was passed in 1905, the Bureau of Census and StatisticsAustralian Bureau of Statistics

The Australian Bureau of Statistics is Australia's national statistical agency. It was created as the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics on 8 December 1905, when the Census and Statistics Act 1905 was given Royal assent. It had its beginnings in section 51 of the Constitution of Australia...

was established in 1906, Bureau of Meteorology was established in 1908 and the Quarantine Act was passed in 1908.

In 1906 Deakin's government amended the Judiciary Act to increase the size of the High Court

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

to five judges, as envisaged in the constitution, and appointed Isaac Isaacs

Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs GCB GCMG KC was an Australian judge and politician, was the third Chief Justice of Australia, ninth Governor-General of Australia and the first born in Australia to occupy that post. He is the only person ever to have held both positions of Chief Justice of Australia and...

and H. B. Higgins

H. B. Higgins

Henry Bournes Higgins , Australian politician and judge, always known in his lifetime as H. B. Higgins, was a highly influential figure in Australian politics and law.-Career:...

to fill the two additional seats. The first protective Federal tariff, the Australian Industries Protection Act was passed. This "New Protection" measure attempted to force companies to pay fair wages by setting conditions for tariff protection, although the Commonwealth had no powers over wages and prices.

The Papua Act of 1905 established an Australian administration for the former British New Guinea and Deakin appointed Hubert Murray

Hubert Murray

Sir John Hubert Plunkett Murray, usually known as Hubert Murray, was a judge and Lieutenant-Governor of Papua from 1908 until his death at Samarai.-Early life:...

as Lieutenant-Governor of Papua in 1908, who ruled it for a 32-year period as a benevolent paternalist. His government passed a bill for the transfer of control of the Northern Territory

Northern Territory

The Northern Territory is a federal territory of Australia, occupying much of the centre of the mainland continent, as well as the central northern regions...

from South Australia to the Commonwealth, which became effective in 1911.

In December 1907, he introduced the first bill to establish compulsory military service, which was also strongly supported by Labor's Watson and Billy Hughes

Billy Hughes

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR , Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923....

. He had long opposed the naval agreements to fund Royal Navy protection of Australia although Barton had agreed in 1902 that the Commonwealth would take over such funding from the colonies. In 1906 he announced that Australia would purchase destroyers, and in 1907 travelled to an Imperial Conference in London to discuss the issue, without success. In 1908 he invited Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

's Great White Fleet

Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the United States Navy battle fleet that completed a circumnavigation of the globe from 16 December 1907 to 22 February 1909 by order of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. It consisted of 16 battleships divided into two squadrons, along with...

to visit Australia, in a symbolic act of independence from Britain. The Surplus Revenue Act of 1908 provided £250,000 for naval expenditure, although these funds were first applied by the Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher was an Australian politician who served as the fifth Prime Minister on three separate occasions. Fisher's 1910-13 Labor ministry completed a vast legislative programme which made him, along with Protectionist Alfred Deakin, the founder of the statutory structure of the new nation...

Labor government, creating the first independent navy

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy is the naval branch of the Australian Defence Force. Following the Federation of Australia in 1901, the ships and resources of the separate colonial navies were integrated into a national force: the Commonwealth Naval Forces...

in the British empire.

Third government 1909–10

In 1908, Deakin was again forced from office by Labor. He then formed a coalition, the "FusionCommonwealth Liberal Party

The Commonwealth Liberal Party was a political movement active in Australia from 1909 to 1916, shortly after federation....

", with his old conservative

Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states and renamed the Anti-Socialist Party in 1906, was an Australian political party, formally organised between 1889 and 1909...

opponent George Reid

George Reid (Australian politician)

Sir George Houstoun Reid, GCB, GCMG, KC was an Australian politician, Premier of New South Wales and the fourth Prime Minister of Australia....

, and returned to power in May 1909 at the head of Australia's first majority government. The Fusion was seen by many as a betrayal of Deakin's liberal principles, and he was called a "Judas" by Sir William Lyne

William Lyne

Sir William John Lyne KCMG , Australian politician, was Premier of New South Wales and a member of the first federal ministry.-Early life:...

. He ordered the dreadnought

Dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of 20th-century battleship. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", and earlier battleships became known as pre-dreadnoughts...

battle cruiser, Australia

HMAS Australia (1911)

HMAS Australia was one of three s built for the defence of the British Empire. Ordered by the Australian government in 1909, she was launched in 1911, and commissioned as flagship of the fledgling Royal Australian Navy in 1913...

and established the financial agreement of 1909, which gave the States annual grants of 25 shillings ($2.50) per person, which was the basis of Commonwealth-state financial arrangements until 1927. In the April 1910 election

Australian federal election, 1910

Federal elections were held in Australia on 13 April 1910. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

his party was soundly defeated by Labor under Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher was an Australian politician who served as the fifth Prime Minister on three separate occasions. Fisher's 1910-13 Labor ministry completed a vast legislative programme which made him, along with Protectionist Alfred Deakin, the founder of the statutory structure of the new nation...

.

Retirement from politics

Deakin retired from Parliament in April 1913 and withdrew from public life. He was president of an Australian commission for the international exhibitionPanama-Pacific International Exposition (1915)

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition was a world's fair held in San Francisco, California between February 20 and December 4 in 1915. Its ostensible purpose was to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal, but it was widely seen in the city as an opportunity to showcase its recovery...

held in San Francisco to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

, but found his duties difficult because of severe progressive memory loss (possibly due to early-onset Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease also known in medical literature as Alzheimer disease is the most common form of dementia. There is no cure for the disease, which worsens as it progresses, and eventually leads to death...

). He became an invalid and died in 1919 of meningoencephalitis

Meningoencephalitis

Meningoencephalitis is a medical condition that simultaneously resembles both meningitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the meninges, and encephalitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the brain.-Causes:...

aged only 63. He is buried in the St. Kilda Cemetery, alongside his wife.

Journalism

Deakin continued to write prolifically throughout his career. He wrote anonymous political commentaries for the London Morning Post even while he was Prime Minister. His account of the federation movement appeared as The Federal Story in 1944 and is a vital primary source for this history. His account of his career in Victorian politics in the 1880s was published as The Crisis in Victorian Politics in 1957. His collected journalism was published as Federated Australia in 1968.Spirituality

Though Deakin always took pains to obscure the spiritual dimensions of his character from public gaze, he felt a strong sense of providenceDivine Providence

In Christian theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's activity in the world. " Providence" is also used as a title of God exercising His providence, and then the word are usually capitalized...

and destiny

Destiny

Destiny or fate refers to a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual...

working in his career. Like Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld was a Swedish diplomat, economist, and author. An early Secretary-General of the United Nations, he served from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 1961. He is the only person to have been awarded a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize. Hammarskjöld...

much later, Deakin's sincere longing for spiritual fulfillment led him to express a sense of unworthiness in his private diaries which mingled with his literary aspirations as a poet.

His private prayer diaries, like those of Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

, express a profound contemplative (though more ecumenical) Christian view of the importance of humility

Humility

Humility is the quality of being modest, and respectful. Humility, in various interpretations, is widely seen as a virtue in many religious and philosophical traditions, being connected with notions of transcendent unity with the universe or the divine, and of egolessness.-Term:The term "humility"...

in seeking divine assistance with his career. "A life, the life of Christ," Deakin wrote, "that is the one thing needful—the only revelation required is there ... We have but to live it." In 1888, as an example relevant to his work for Federation, Deakin prayed: "Oh God, grant me that judgment & forsight which will enable me to serve my country—guide me and strengthen me, so that I may follow & persuade others to follow the path which shall lead to the elevation of national life & thought & permanence of well earned prosperity—give me light & truth & influence for the highest & the highest only." As Walter Murdoch pointed out, "[Deakin] believed himself to be inspired, and to have a divine message and mission."

Historian Manning Clark

Manning Clark

Charles Manning Hope Clark, AC , an Australian historian, was the author of the best-known general history of Australia, his six-volume A History of Australia, published between 1962 and 1987...

, whose History of Australia cites extensively from his studies of Deakin's private diaries in the National Library of Australia

National Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia is the largest reference library of Australia, responsible under the terms of the National Library Act for "maintaining and developing a national collection of library material, including a comprehensive collection of library material relating to Australia and the...

, wrote: "By reading the world's scriptures and mystics

Mysticism

Mysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

a deep peace had settled far inside [Deakin]: now he felt a 'serenity at the core of my heart.' He wanted to know whether participation in the world's affairs would disturb that serenity ... he was tormented by the thought that the emptiness of the man within corresponded with the emptiness of society at large where Mammon

Mammon

Mammon is a term, derived from the Christian Bible, used to describe material wealth or greed, most often personified as a deity, and sometimes included in the seven princes of Hell.-Etymology:...

had found a new demesne to infest."

Legacy

William Lyne

Sir William John Lyne KCMG , Australian politician, was Premier of New South Wales and a member of the first federal ministry.-Early life:...

reviled him as a traitor.

He had a long and happy marriage and was survived by his wife and their three daughters:

- Ivy (1883–1970) married Herbert Brookes.

- Stella (1886–1976) married Sir David RivettDavid RivettSir David Rivett, KCMG was an Australian chemist and science administrator.Rivett was born at Port Esperance, Tasmania, Australia. He studied at Wesley College in Melbourne and the University of Melbourne, where he was a member of Queen's College, obtaining a BSc in 1906 and a DSc in 1913...

. - Vera (1891–1978) married (later Sir) Thomas WhiteThomas White (Australian politician)Sir Thomas Walter White KBE DFC was an Australian politician.-Early life and World War I:White was born at Hotham, North Melbourne, Victoria and educated at Moreland State School. In August 1914, he began training as an officer in the Australian Flying Corps at Point Cook...

.

His descendants are still active in Melbourne political and business circles (notably his great-grandson Tom Harley), and he is regarded as a founding father by the modern Liberal Party

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Founded a year after the 1943 federal election to replace the United Australia Party, the centre-right Liberal Party typically competes with the centre-left Australian Labor Party for political office...

. The Division of Deakin

Division of Deakin

The Division of Deakin is anAustralian Electoral Division in Victoria. It is named for Alfred Deakin, three times Prime Minister of Australia. The division was created in 1937, initially as a rural seat, but since 1949 it has been located in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne, today taking in...

, Alfred Deakin High School

Alfred Deakin High School

Alfred Deakin High School is a government secondary school in Deakin, Australian Capital Territory, covering years 7 to 10 in the Territory's education system. It is named after the second Australian Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin.- History :...

, Deakin University

Deakin University

Deakin University is an Australian public university with nearly 40,000 higher education students in 2010. It receives more than A$600 million in operating revenue annually, and controls more than A$1.3 billion in assets. It received more than A$35 million in research income in 2009 and had 835...

, Deakin Avenue in the rural city of Mildura, Deakin House at Melbourne Grammar School

Melbourne Grammar School

Melbourne Grammar School is an independent, Anglican, day and boarding school predominantly for boys, located in South Yarra and Caulfield, suburbs of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia....

and the Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

suburb of Deakin

Deakin, Australian Capital Territory

Deakin is a suburb of Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. Deakin is named after Alfred Deakin, second prime minister of Australia...

are named after him.

In 1969, Australia Post

Australia Post

Australia Post is the trading name of the Australian Government-owned Australian Postal Corporation .-History:...

honoured him on a postage stamp

Postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

bearing his portrait.

See also

- First Deakin MinistryFirst Deakin MinistryThe First Deakin Ministry was the second Australian Commonwealth ministry, and ran from 24 September 1903 to 27 April 1904.Protectionist Party...

- Second Deakin MinistrySecond Deakin MinistryThe Second Deakin Ministry was the fifth Australian Commonwealth ministry, and ran from 5 July 1905 to 12 December 1906.Protectionist Party...

- Third Deakin MinistryThird Deakin MinistryThe Third Deakin Ministry was the sixth Australian Commonwealth ministry, and ran from 12 December 1906 to 13 November 1908.Protectionist Party...

- Fourth Deakin MinistryFourth Deakin MinistryThe Fourth Deakin Ministry was the eighth Australian Commonwealth ministry, and ran from 2 June 1909 to 29 April 1910.Commonwealth Liberal Party*Hon Alfred Deakin, MP: Prime Minister *Hon Joseph Cook, MP: Minister for Defence...

Further reading

- Birrell, Robert (1995), A Nation of Our Own, Longman Australia, Melbourne. ISBN 0-582-87549-8

- Gabay, Al (1992), The Mystic Life of Alfred Deakin, Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, Colin AColin HughesColin Anfield Hughes is an Australian academic specializing in electoral politics and government.He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees from Columbia University and his Ph.D from the London School of Economics. In 1966, along with John S...

(1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.22. ISBN 0-19-550471-2 - La Nauze, John A (1965), Alfred Deakin: A Biography, two volumes, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria.

External links

- Alfred Deakin – Australia's Prime Ministers / National Archives of Australia

- Guide to the papers of Alfred Deakin held and selectively digitised by the National Library of Australia

- Alfred Deakin Prime Ministerial Library

- Deakin University

- Alfred Deakin's personal library on LibraryThingLibraryThingLibraryThing is a social cataloging web application for storing and sharing book catalogs and various types of book metadata. It is used by individuals, authors, libraries and publishers....