Aleksandr Kolchak

Encyclopedia

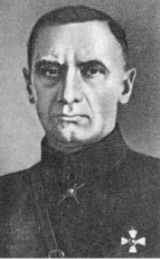

Aleksandr Vasiliyevich Kolchak was a Russian naval

commander, polar explorer and later - Supreme ruler (head of all the counter-revolutionary anti-communist White forces

during the Russian Civil War

). Supreme ruler of Russia (1918–1920), was recognized in this position by all the heads of the White movement

, "De jure

" - Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

, "De facto

" - Entente States

. He was also a prominent expert on naval mine

s and a member of the Russian Geographical Society

.

Among Kolchak's awards are the St. George Gold Sword for Bravery

given for his actions in the battle of Port Arthur

and the Great Gold Constantine Medal from the Russian Geographic Society. Soviet maps depicted Kolchak Island

up until the mid-1930s.

.jpg) Kolchak was born in Saint Petersburg

Kolchak was born in Saint Petersburg

in 1874 into a military family descending from the 18th-century Romanian mercenary Iliaş Colceag

. His father was a retired major-general of the Marine Artillery, who was actively engaged in the siege of Sevastopol in 1854-55 and after his retirement worked as an engineer in ordnance works near St. Petersburg. Kolchak was educated for a naval career, graduating from the Naval Cadet Corps

in 1894 and joining the 7th Naval Battalion of the city. He was soon transferred to the Far East

, serving in Vladivostok

from 1895 to 1899. He returned to western Russia and was based at Kronstadt, joining the Polar expedition of Eduard Toll

on the ship Zarya

in 1900 as a hydrologist.

After considerable hardship, Kolchak returned in December 1902; Eduard Toll with three other members went further north and were lost. Kolchak took part in two Arctic expeditions and for a while was nickname

d "Kolchak-Poliarnyi" ("Kolchak the Polar"). For his explorations Kolchak received the highest award of the Russian Geographical Society

.

In December 1903, Kolchak was on his way back to St. Petersburg, there to marry his fiancee Sophia Omirova. Not far from Irkutsk

, he received notice of the start of war with the Empire of Japan

and hastily summoned his bride and her father to Siberia

by telegram for a wedding before heading directly to Port Arthur

. In the early stages of the Russo-Japanese War

, he served as watch officer on the cruiser , and later commanded the destroyer

. He made several night sorties to lay naval mine

s, one of which succeeded in sinking the Japanese cruiser . He was decorated with the Order of St. Anna

4th class for the exploit. As the blockade of the port tightened and the Siege of Port Arthur

intensified, he was given command of a coastal artillery

battery. He was wounded in the final battles for Port Arthur and taken as a prisoner of war

to Nagasaki, where he spent four months. His poor health (rheumatism

- a consequence of his polar expeditions) - led to his repatriation before the end of the war. He was awarded the Golden Sword of St. George with the inscription "For Bravery" on his return to Russia.

Returning to Saint Petersburg

in April 1905, Kolchak was promoted to lieutenant commander. Kolchak took part in the rebuilding of the Imperial Russian Navy, which had been almost completely destroyed during the war. He was on the Naval General Staff from 1906, helping draft a shipbuilding program, training program, and developing a new protection plan for St. Petersburg and the Gulf of Finland

area.

Kolchak took part in designing the special icebreaker

s Taimyr and Vaigach, launched in 1909 spring 1910. Based in Vladivostok, these vessels were sent on a cartographic expedition to the Bering Strait

and Cape Dezhnev

. Kolchak commanded the Vaigach during this expedition and later worked at the Academy of Sciences with the materials collected by him during expeditions. His study, The Ices of the Kara and Siberian Seas, was printed in the Proceedings of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences and is considered the most important work on this subject. Extracts from it were published under the title "The Arctic Pack and the Polynya" in the volume issued in 1929 by the American Geographical Society, Problems of Polar Research.

In 1910 he returned to the Naval General Staff, and in 1912 he was assigned to serve in the Russian Baltic Fleet.

. Admiral Essen

was not satisfied to remain only on the defensive and ordered Kolchak to prepare a scheme for attacking the approaches of the German naval bases. During the autumn and winter of 1914-1915, Russian destroyers and cruisers started a series of dangerous night operations, laying mines at the approaches to Kiel

and Danzig. Kolchak, being of the opinion that the person responsible for planning operations should take part in their execution, was always on board those ships which carried out the operations and sometimes took direct command of the destroyer flotillas.

He was promoted to Vice-Admiral in August 1916, the youngest man at that rank, and was made commander of the Black Sea Fleet

, replacing Admiral Eberhart

. Kolchak's primary mission was to support General Yudenich

in his operations against the Ottoman Empire

. He also was tasked with the job of countering any U-boat

threat and to begin planning an invasion of the Bosphorus (which was never carried out). Kolchak's fleet was successful at sinking Turkish colliers. Because there was no railroad linking the coal mines of eastern Turkey with Constantinople

, the Russian fleet's attacks on the Turkish coal ships caused the Ottoman government much hardship. In 1916, in a model combined Army-Navy assault, the Russian Black Sea fleet helped the Russian army to take the Ottoman city of Trebizond (modern Trabzon

).

One notable disaster took place under Kolchak's watch: the dreadnought

Empress Maria

blew up in the port of Sevastopol

on October 7, 1916. A careful investigation failed to determine the cause of the explosion; it could have been accidental or sabotage.

in 1917, the Black Sea fleet descended into political chaos. Kolchak was removed from command of the fleet in June and travelled to Petrograd. On his arrival at Petrograd, Kolchak was invited to a meeting of the Provisional Government

. There he presented his view on the condition of the Russian armed forces and their complete demoralisation. He stated that the only way to save the country was to reestablish discipline and restore capital punishment in the army and navy.

During this time many organisations and newspapers with a nationalist tendency spoke of him as a future dictator. A number of new and secret organisations had sprung up in Petrograd which had as their object the suppression of the Bolshevist movement and the removal of the extremist members of the Government. Some of these organisations asked Kolchak to accept the leadership.

When the news was received by the then Naval Minister of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky

, he ordered Kolchak to leave immediately for America (Admiral James H. Glennon

, member of American mission, headed by Senator Elihu Root

invited Kolchak to go to America in order to give the American Navy Department information on Bosphorus). On 19 August 1917 Kolchak with several officers left Petrograd for Britain

and the United States

as a quasi-official military observer. When passing through London he was greeted cordially by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, who offered him transport on board a British cruiser on his way to Halifax. The journey to America proved to be unnecessary, as by the time Kolchak arrived, the US had given up the idea of any independent action in the Dardanelles. Kolchak visited the American Fleet and its ports, and decided to return to Russia via Japan.

and then Manchuria

. Kolchak was a supporter of the Provisional Government and returned to Russia, through Vladivostok

, in 1918. Kolchak was an absolute supporter of the Allied cause against Germany

, and initially hearing of the Bolshevik coup on November 7, 1917, he offered to enlist in the British Army

to continue the struggle. Initially, the British were inclined to accept Kolchak’s offer, and there were plans to send Kolchak to Mesopotamia

(modern Iraq

), but London

decided that Kolchak could do more for the Allied cause by overthrowing the Bolsheviks and bringing Russia back into the war on the Allied side. Reluctantly, Kolchak accepted the British suggestions and with a heavy sense of foreboding, Kolchak returned to Russia. Arriving in Omsk

, Siberia

, en route to enlisting with the Volunteer Army

, he agreed to become a minister in the (White) Siberian Regional Government. Joining a fourteen man cabinet, he was a prestige figure; the government hoped to play on the respect he had with the Allies, especially the head of the British military mission, General Alfred Knox

.

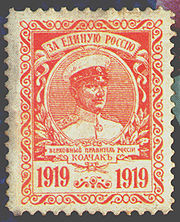

In November 1918, the unpopular regional government was overthrown in a military coup d'etat

. Kolchak had returned to Omsk on November 16 from an inspection tour. He was approached and refused to take power. The Socialist-Revolutionary

(SR) Directory leader and members were arrested on November 18 by a troop of Cossack

s under ataman

Krasilnikov. The remaining cabinet members met and voted for Kolchak to become the head of government with dictatorial powers. He was named Supreme Ruler (Verkhovnyi Pravitel), and he promoted himself to Admiral

. The arrested SR politicians were expelled from Siberia and ended up in Europe.

He issued the following manifesto to the population:

The SR leaders in Russia denounced Kolchak and called for him to be killed. Their activities resulted in a small revolt in Omsk

on December 22, 1918, which was quickly put down by Cossacks and the Czechoslovak Legion, who summarily executed almost 500 rebels. The SRs opened negotiations with the Bolsheviks and in January 1919 the SR People's Army joined with the Red Army

.

Kolchak pursued a policy of persecuting revolutionaries as well as Socialists of several factions. Kolchak’s government issued a decree on 3 December 1918 stating, “In order to preserve the system and rule of the Supreme Ruler, articles of the criminal code of Imperial Russia were revised, Articles 99 and 100 of which established capital punishment for assassination attempts on the Supreme Ruler and for attempting to overthrow the authorities. “Insults written, printed, and oral, are punishable by imprisonment under Article 103. Bureaucratic sabotage under Article 329 was punishable by hard labor from 15 to 20 years.

On April 11, 1919, the Kolchak's government adopted Regulation no. 428, “About the dangers of public order due to ties with the Bolshevik Revolt”. The legislation was published in the Omsk newspaper Omsk Gazette (no. 188 of 19 July 1919). It provided a term of five years of prison for “individuals considered a threat to the public order because of their ties in any way with the Bollshevik revolt.” In the case of unauthorized return from exile, there could be hard labor from 4 to 8 years. Articles 99-101 allowed the death penalty, forced labor and imprisonment, repression by military courts, and imposed no investigation commissions.

Kolchak acknowledged all of Russia's debts, returned factories and plants to their owners, granted concessions to foreign investors, dispersed trade unions, persecuted Marxists, and disbanded the soviets. Kolchak's agrarian policy was directed toward restoring private land ownership. The former Tsarist laws were restored. There was brutal repression committed by Kolchak's regime: in Ekaterinburg alone the Great Soviet Encyclopedia alleges that more than 25,000 people were shot or tortured to death. In March 1919 Kolchak himself demanded one of his generals to "follow the example of the Japanese who, in the Amur region, had exterminated the local population."

Sovietskaya Rossiya, an "official organ" of Soviet Bureau

established by Ludwig Martens

, quoted a Menshevik

organ Vsegda Vperyod alleging that Kolchak's men used mass floggings and razed entire villages to the ground with artillery fire. 4,000 peasants allegedly became victims of field courts and punitive expeditions and that all dwellings of rebels were burned down.

An excerpt from the order of the government of Yenisei county in Irkutsk province, General. S. Rozanov said:

There was prominent underground resistance in the regions controlled by Kolchak's government. These partisans were especially strong in the provinces of Altai

and Yeniseysk

. In the summer of 1919 partisans of Altai Region united to form the Western Siberian Peasants' Red Army (25,000 men). The Taseev Soviet Partisan Republic was founded south-east of Yeniseysk in early 1919. By the fall of 1919, Kolchak's rear was completely disintegrating. About 100,000 Siberian Communists seized vast regions from Kolchak's regime even before the approach of the Red Army. In February 1920, some 20,000 partisans took control of the Amur region

.

British left-wing historian Edward Hallett Carr

wrote,

On the contrary, a former Chief of Staff

to Admiral Kolchak wrote,

and the Czech Rudolf Gajda

seized Perm

in late December 1918 and after a pause other forces spread out from this strategic base. The plan was for three main advances – Gajda to take Archangel

, Khanzhin to capture Ufa

and the Cossack

s under Alexander Dutov

to capture Samara

and Saratov

. Kolchak had put around 110,000 men into the field facing roughly 95,000 Bolshevik troops. Kolchak's good relations with General Alfred Knox meant that his forces were partly armed, munitioned and uniformed by the British (up to August 1919 the British spent an official $239 million aiding the Whites, although Churchill disputed this figure at the time as an "absurd exaggeration").

The White forces took Ufa

in March 1919 and pushed on from there to take Kazan

and approach Samara on the Volga River

. Anti-Communist risings in Simbirsk, Kazan

, Viatka

, and Samara

assisted their endeavours. The newly-formed Red Army proved unwilling to fight and retreated, allowing the Whites to advance to a line stretching from Glazov

through Orenburg

to Uralsk. Kolchak's territories covered over 300,000 km² and held around 7 million people. In April, the alarmed Bolshevik Central Executive Committee

made defeating Kolchak its top priority. But as the spring thaw arrived Kolchak's position degenerated – his armies had outrun their supply lines, they were exhausted, and the Red Army was pouring newly raised troops into the area.

Kolchak had also aroused the dislike of potential allies including the Czechoslovak Legion and the Polish 5th Rifle Division

. They withdrew from the conflict in October 1918 but remained a presence, their new leader Maurice Janin

regarded Kolchak as an instrument of the British and was pro-SR. Kolchak could not count on Japanese aid either; the Japanese feared he would interfere with their occupation of Far Eastern Russia and refused him assistance, creating a 'buffer state

' to the east of Lake Baikal

under Cossack control. The 7,000 or so American troops in Siberia were strictly neutral regarding "internal Russian affairs" and served only to maintain the operation of the Trans-Siberian railroad

in the Far East. The American commander, General William S. Graves

, personally disliked the Kolchak government, which he saw as Monarchist and autocratic, a view that was shared by the American President

, Woodrow Wilson

. As a result, both refused to grant him any aid.

When the Red forces managed to reorganise and turn the attack against Kolchak, from 1919 he quickly lost ground. The Red counter-attack began in late April at the centre of the White line, aiming for Ufa. The fighting was fierce as, unlike earlier, both sides fought hard. Ufa was taken by the Red Army on June 9 and later that month the Red forces under Tukhachevsky broke through the Urals. Freed from the geographical constraints of the mountains, the Reds made rapid progress, capturing Chelyabinsk

When the Red forces managed to reorganise and turn the attack against Kolchak, from 1919 he quickly lost ground. The Red counter-attack began in late April at the centre of the White line, aiming for Ufa. The fighting was fierce as, unlike earlier, both sides fought hard. Ufa was taken by the Red Army on June 9 and later that month the Red forces under Tukhachevsky broke through the Urals. Freed from the geographical constraints of the mountains, the Reds made rapid progress, capturing Chelyabinsk

on July 25 and forcing the White forces to the north and south to fall back to avoid being isolated. The White forces re-established a line along the Tobol and the Ishim rivers to temporarily halt the Reds. They held that line until October, but the constant loss of men killed or wounded was beyond the White rate of replacement. Reinforced, the Reds broke through on the Tobol in mid-October and by November the White forces were falling back towards Omsk in a disorganised mass. The Reds were sufficiently confident to start redeploying some of their forces southwards to face Anton Denikin.

Kolchak also came under threat from other quarters: local opponents began to agitate and international support began to wane, with even the British turning more towards Denikin. Gajda

, dismissed from command of the northern army, staged an abortive coup in mid-November. Omsk was evacuated on November 14 and the Red Army took the city without any serious resistance, capturing large amounts of ammunition, almost 50,000 soldiers, and ten generals. As there was a continued flood of refugees eastwards, typhus

became a serious problem.

Kolchak had left Omsk on the 13th for Irkutsk

along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Travelling a section of track controlled by the Czechoslovaks he was sidetracked and stopped; by December his train had only reached Nizhneudinsk. In late December Irkutsk fell under the control of a leftist group (including SRs) and formed the Political Centre

. One of their first actions was to dismiss Kolchak. When he heard of this on January 4, 1920, he announced his resignation, giving his office to Denikin and passing control of his remaining forces around Irkutsk to the ataman

, G. M. Semyonov. The transfer of power to Semyonov proved a particularly ill-considered move.

It appears that Kolchak was then promised safe passage by the Czechoslovaks to the British military mission in Irkutsk. Instead, he was handed over to the leftist authorities in Irkutsk on January 14. On January 20 the government in Irkutsk gave power to a Bolshevik military committee. The White Army under command of Vladimir Kappel

It appears that Kolchak was then promised safe passage by the Czechoslovaks to the British military mission in Irkutsk. Instead, he was handed over to the leftist authorities in Irkutsk on January 14. On January 20 the government in Irkutsk gave power to a Bolshevik military committee. The White Army under command of Vladimir Kappel

rushed toward Irkutsk while Kolchak was "investigated" before a commission of five men from January 21 to February 6. Despite the arrival of a contrary order from Moscow, Admiral Kolchak was summarily sentenced to death along with his Prime Minister, Viktor Pepelyayev

.

Both prisoners were brought before a firing squad in the early morning of 7 February 1920. According to eyewitnesses, Kolchak was entirely calm and unafraid, "like and Englishman." The Admiral asked the commander of the firing squad, "Would you be so good as to get a message sent to my wife in Paris

to say that I bless my son?" The commander responded, "I'll see what can be done, if I don't forget about it."

A priest of the Russian Orthodox Church

then gave the last rites

to both men. The squad fired and both men fell. The bodies were kicked and prodded down an escarpment and dumped under the ice of the frozen Angara River

. When the White Army learned about the executions, the decision was made to withdraw farther east. The Great Siberian Ice March

followed. The Red Army did not enter Irkutsk until March 7, and only then was the news of Kolchak's death officially released.

.

Kolchak failed to convince the potentially friendly states of Finland

, Poland

, or the Baltic states

to join with him against the Bolsheviks. He was unable to win diplomatic recognition from any nation in the world, even Britain

(though the British did support him to some degree). He alienated the Czechoslovak Legion, which for a time was a powerful organized military force and very strongly anti-Bolshevik. As was mentioned above, the American commander, General Graves

, disliked Kolchak and refused to lend him any military aid at all.

After decades of being vilified by the Soviet government, Kolchak is now a controversial historic figure in post-Soviet Russia. The "For Faith and Fatherland

" movement has attempted to rehabilitate

his reputation. However, two rehabilitation requests have been denied, by a regional military court in 1999 and by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation

in 2001. In 2004, the Constitutional Court

of Russia returned the Kolchak case to the military court for another hearing.

Monuments dedicated to Kolchak were built in Saint Petersburg in 2002 and in Irkutsk in 2004, despite objections from some former Communist and left-wing politicians and former Soviet army veterans. There is also a Kolchak Island

. The modern Russian Navy thought about naming the third ship of the new s, Admiral Kolchak to commemorate the Admiral but the time was not right and the name was not assigned.

(Адмиралъ), was released in Russia on 9 October 2008. The film portrays the Admiral (Konstantin Khabensky

) as a tragic hero

with a very deep love for his country. Elizaveta Boyarskaya

appears as his common law wife

, Anna Timireva.

Director Andrei Kravchuk

described the film as follows,

Contrary to popular opinion, Kolchak was not the author of the Shine, Shine, My Star

art song

.

Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy refers to the Tsarist fleets prior to the February Revolution.-First Romanovs:Under Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich, construction of the first three-masted ship, actually built within Russia, was completed in 1636. It was built in Balakhna by Danish shipbuilders from Holstein...

commander, polar explorer and later - Supreme ruler (head of all the counter-revolutionary anti-communist White forces

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

during the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

). Supreme ruler of Russia (1918–1920), was recognized in this position by all the heads of the White movement

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

, "De jure

De jure

De jure is an expression that means "concerning law", as contrasted with de facto, which means "concerning fact".De jure = 'Legally', De facto = 'In fact'....

" - Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

, "De facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

" - Entente States

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente was the name given to the alliance among Britain, France and Russia after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907....

. He was also a prominent expert on naval mine

Naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an enemy vessel...

s and a member of the Russian Geographical Society

Russian Geographical Society

The Russian Geographical Society is a learned society, founded on 6 August 1845 in Saint Petersburg, Russia.-Imperial Geographical Society:Prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917, it was known as the Imperial Russian Geographical Society....

.

Among Kolchak's awards are the St. George Gold Sword for Bravery

Gold Sword for Bravery

The Gold Sword for Bravery was a Russian Empire award for bravery. It was set up with two grades on 27 July 1720 by Peter the Great, reclassified as a public order in 1807 and abolished in 1917. From 1913 to 1917 it was renamed the St George Sword and considered as one of the grades of the Order...

given for his actions in the battle of Port Arthur

Battle of Port Arthur

The Battle of Port Arthur was the starting battle of the Russo-Japanese War...

and the Great Gold Constantine Medal from the Russian Geographic Society. Soviet maps depicted Kolchak Island

Kolchak Island

Kolchak Island or Kolchaka Island , is an island in the Kara Sea located NE of the Shturmanov Peninsula, in an area of skerries south of the Nordenskiöld Archipelago. Compared to other large islands in the area it has a quite regular shape....

up until the mid-1930s.

Early life and career

.jpg)

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

in 1874 into a military family descending from the 18th-century Romanian mercenary Iliaş Colceag

Ilias Colceag

Iliaş Colceag was a Moldavian mercenary and military commander, in the Ottoman and Russian Empire.He entered the Ottoman army and was first posted in Bosnia. Here, he converted to Islam and took the name of Hussein. He distinguished himself during the Russo-Turkish War of 1710/11 being promoted...

. His father was a retired major-general of the Marine Artillery, who was actively engaged in the siege of Sevastopol in 1854-55 and after his retirement worked as an engineer in ordnance works near St. Petersburg. Kolchak was educated for a naval career, graduating from the Naval Cadet Corps

Sea Cadet Corps (Russia)

The Sea Cadet Corps , occasionally translated as the Marine Cadet Corps or the Naval Cadet Corps, is an educational establishment for training Naval officers for the Russian Navy in Saint Petersburg.It is the oldest existing high school in Russia.-History:...

in 1894 and joining the 7th Naval Battalion of the city. He was soon transferred to the Far East

Russian Far East

Russian Far East is a term that refers to the Russian part of the Far East, i.e., extreme east parts of Russia, between Lake Baikal in Eastern Siberia and the Pacific Ocean...

, serving in Vladivostok

Vladivostok

The city is located in the southern extremity of Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, which is about 30 km long and approximately 12 km wide.The highest point is Mount Kholodilnik, the height of which is 257 m...

from 1895 to 1899. He returned to western Russia and was based at Kronstadt, joining the Polar expedition of Eduard Toll

Eduard Toll

Eduard Gustav von Toll was a Baltic German geologist and Arctic explorer in Russian service. Often referred to as Baron von Toll or as Eduard v. Toll, in Russia he is known as Eduard Vasiliyevich Toll . Eduard Toll was born on and he died in 1902 in an unknown location in the Arctic Ocean)...

on the ship Zarya

Zarya (polar ship)

Zarya was a steam- and sail-powered brig used by the Russian Academy of Sciences for a polar exploration during 1900–1903.Toward the end of the 19th century, the Russian Academy of Sciences sought to build a general-purpose research vessel for long-term expeditions. The first such Russian...

in 1900 as a hydrologist.

After considerable hardship, Kolchak returned in December 1902; Eduard Toll with three other members went further north and were lost. Kolchak took part in two Arctic expeditions and for a while was nickname

Nickname

A nickname is "a usually familiar or humorous but sometimes pointed or cruel name given to a person or place, as a supposedly appropriate replacement for or addition to the proper name.", or a name similar in origin and pronunciation from the original name....

d "Kolchak-Poliarnyi" ("Kolchak the Polar"). For his explorations Kolchak received the highest award of the Russian Geographical Society

Russian Geographical Society

The Russian Geographical Society is a learned society, founded on 6 August 1845 in Saint Petersburg, Russia.-Imperial Geographical Society:Prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917, it was known as the Imperial Russian Geographical Society....

.

In December 1903, Kolchak was on his way back to St. Petersburg, there to marry his fiancee Sophia Omirova. Not far from Irkutsk

Irkutsk

Irkutsk is a city and the administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia, one of the largest cities in Siberia. Population: .-History:In 1652, Ivan Pokhabov built a zimovye near the site of Irkutsk for gold trading and for the collection of fur taxes from the Buryats. In 1661, Yakov Pokhabov...

, he received notice of the start of war with the Empire of Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

and hastily summoned his bride and her father to Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

by telegram for a wedding before heading directly to Port Arthur

Lüshunkou

Lüshunkou is a district in the municipality of Dalian, Liaoning province, China. Also called Lüshun City or Lüshun Port, it was formerly known as both Port Arthur and Ryojun....

. In the early stages of the Russo-Japanese War

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

, he served as watch officer on the cruiser , and later commanded the destroyer

Destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast and maneuverable yet long-endurance warship intended to escort larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against smaller, powerful, short-range attackers. Destroyers, originally called torpedo-boat destroyers in 1892, evolved from...

. He made several night sorties to lay naval mine

Naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an enemy vessel...

s, one of which succeeded in sinking the Japanese cruiser . He was decorated with the Order of St. Anna

Order of St. Anna

The Order of St. Anna ) is a Holstein and then Russian Imperial order of chivalry established by Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp on 14 February 1735, in honour of his wife Anna Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great of Russia...

4th class for the exploit. As the blockade of the port tightened and the Siege of Port Arthur

Siege of Port Arthur

The Siege of Port Arthur , 1 August 1904 – 2 January 1905, the deep-water port and Russian naval base at the tip of the Liaotung Peninsula in Manchuria, was the longest and most violent land battle of the Russo-Japanese War....

intensified, he was given command of a coastal artillery

Coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications....

battery. He was wounded in the final battles for Port Arthur and taken as a prisoner of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

to Nagasaki, where he spent four months. His poor health (rheumatism

Rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorder is a non-specific term for medical problems affecting the joints and connective tissue. The study of, and therapeutic interventions in, such disorders is called rheumatology.-Terminology:...

- a consequence of his polar expeditions) - led to his repatriation before the end of the war. He was awarded the Golden Sword of St. George with the inscription "For Bravery" on his return to Russia.

Returning to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

in April 1905, Kolchak was promoted to lieutenant commander. Kolchak took part in the rebuilding of the Imperial Russian Navy, which had been almost completely destroyed during the war. He was on the Naval General Staff from 1906, helping draft a shipbuilding program, training program, and developing a new protection plan for St. Petersburg and the Gulf of Finland

Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland and Estonia all the way to Saint Petersburg in Russia, where the river Neva drains into it. Other major cities around the gulf include Helsinki and Tallinn...

area.

Kolchak took part in designing the special icebreaker

Icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller vessels .For a ship to be considered an icebreaker, it requires three traits most...

s Taimyr and Vaigach, launched in 1909 spring 1910. Based in Vladivostok, these vessels were sent on a cartographic expedition to the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

and Cape Dezhnev

Cape Dezhnev

Cape Dezhnyov or Cape Dezhnev is a cape that forms the eastmost mainland point of Eurasia. It is located on the Chukchi Peninsula in the very thinly populated Chukotka Autonomous Okrug of Russia. This cape is located between the Bering Sea and the Chukchi Sea, across from Cape Prince of Wales in...

. Kolchak commanded the Vaigach during this expedition and later worked at the Academy of Sciences with the materials collected by him during expeditions. His study, The Ices of the Kara and Siberian Seas, was printed in the Proceedings of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences and is considered the most important work on this subject. Extracts from it were published under the title "The Arctic Pack and the Polynya" in the volume issued in 1929 by the American Geographical Society, Problems of Polar Research.

In 1910 he returned to the Naval General Staff, and in 1912 he was assigned to serve in the Russian Baltic Fleet.

First World War

After the outbreak of war initially on the flagship Pogranichnik, Kolchak oversaw the laying of extensive coastal defensive minefields and commanded the naval forces in the Gulf of RigaGulf of Riga

The Gulf of Riga, or Bay of Riga, is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia. According to C.Michael Hogan, a saline stratification layer is found at a depth of approximately seventy metres....

. Admiral Essen

Nikolai Essen

Nikolai Ottovich Essen was a Russian naval commander and admiral from the Baltic German Essen family. For more than two centuries his ancestors had served in the Navy, and seven had been awarded the Order of St...

was not satisfied to remain only on the defensive and ordered Kolchak to prepare a scheme for attacking the approaches of the German naval bases. During the autumn and winter of 1914-1915, Russian destroyers and cruisers started a series of dangerous night operations, laying mines at the approaches to Kiel

Kiel

Kiel is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 238,049 .Kiel is approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the north of Germany, the southeast of the Jutland peninsula, and the southwestern shore of the...

and Danzig. Kolchak, being of the opinion that the person responsible for planning operations should take part in their execution, was always on board those ships which carried out the operations and sometimes took direct command of the destroyer flotillas.

He was promoted to Vice-Admiral in August 1916, the youngest man at that rank, and was made commander of the Black Sea Fleet

Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet is a large operational-strategic sub-unit of the Russian Navy, operating in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea since the late 18th century. It is based in various harbors of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov....

, replacing Admiral Eberhart

Andrei Eberhardt

Andrei Augostovich Eberhardt - was an Admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy of Swedish ancestry.Eberhardt graduated from the Marine Cadet Corps in 1878. From 1882 to 1884 he served in the Pacific Fleet as a signals officer...

. Kolchak's primary mission was to support General Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolaevich Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolaevich Yudenich , was a commander of the Russian Imperial Army during World War I. He was a leader of the anti-communist White movement in Northwestern Russia during the Civil War.-Early life:...

in his operations against the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. He also was tasked with the job of countering any U-boat

U-boat

U-boat is the anglicized version of the German word U-Boot , itself an abbreviation of Unterseeboot , and refers to military submarines operated by Germany, particularly in World War I and World War II...

threat and to begin planning an invasion of the Bosphorus (which was never carried out). Kolchak's fleet was successful at sinking Turkish colliers. Because there was no railroad linking the coal mines of eastern Turkey with Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

, the Russian fleet's attacks on the Turkish coal ships caused the Ottoman government much hardship. In 1916, in a model combined Army-Navy assault, the Russian Black Sea fleet helped the Russian army to take the Ottoman city of Trebizond (modern Trabzon

Trabzon

Trabzon is a city on the Black Sea coast of north-eastern Turkey and the capital of Trabzon Province. Trabzon, located on the historical Silk Road, became a melting pot of religions, languages and culture for centuries and a trade gateway to Iran in the southeast and the Caucasus to the northeast...

).

One notable disaster took place under Kolchak's watch: the dreadnought

Dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of 20th-century battleship. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", and earlier battleships became known as pre-dreadnoughts...

Empress Maria

Battleship Imperatritsa Mariya

Imperatritsa Mariya was an dreadnought of the Imperial Russian Navy, lead ship of her class. Construction began before World War I and she saw service with the Black Sea Fleet during the war...

blew up in the port of Sevastopol

Sevastopol

Sevastopol is a city on rights of administrative division of Ukraine, located on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea peninsula. It has a population of 342,451 . Sevastopol is the second largest port in Ukraine, after the Port of Odessa....

on October 7, 1916. A careful investigation failed to determine the cause of the explosion; it could have been accidental or sabotage.

Revolution

After the February RevolutionFebruary Revolution

The February Revolution of 1917 was the first of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. Centered around the then capital Petrograd in March . Its immediate result was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire...

in 1917, the Black Sea fleet descended into political chaos. Kolchak was removed from command of the fleet in June and travelled to Petrograd. On his arrival at Petrograd, Kolchak was invited to a meeting of the Provisional Government

Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was the short-lived administrative body which sought to govern Russia immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II . On September 14, the State Duma of the Russian Empire was officially dissolved by the newly created Directorate, and the country was...

. There he presented his view on the condition of the Russian armed forces and their complete demoralisation. He stated that the only way to save the country was to reestablish discipline and restore capital punishment in the army and navy.

During this time many organisations and newspapers with a nationalist tendency spoke of him as a future dictator. A number of new and secret organisations had sprung up in Petrograd which had as their object the suppression of the Bolshevist movement and the removal of the extremist members of the Government. Some of these organisations asked Kolchak to accept the leadership.

When the news was received by the then Naval Minister of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky was a major political leader before and during the Russian Revolutions of 1917.Kerensky served as the second Prime Minister of the Russian Provisional Government until Vladimir Lenin was elected by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets following the October Revolution...

, he ordered Kolchak to leave immediately for America (Admiral James H. Glennon

James H. Glennon

James Henry Glennon was a United States Navy officer. He saw action in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, and World War I.-Early life and career, to World War I:...

, member of American mission, headed by Senator Elihu Root

Elihu Root

Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C...

invited Kolchak to go to America in order to give the American Navy Department information on Bosphorus). On 19 August 1917 Kolchak with several officers left Petrograd for Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

as a quasi-official military observer. When passing through London he was greeted cordially by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, who offered him transport on board a British cruiser on his way to Halifax. The journey to America proved to be unnecessary, as by the time Kolchak arrived, the US had given up the idea of any independent action in the Dardanelles. Kolchak visited the American Fleet and its ports, and decided to return to Russia via Japan.

Russian Civil War

At the time of the revolution in November 1917, he was in JapanJapan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

and then Manchuria

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

. Kolchak was a supporter of the Provisional Government and returned to Russia, through Vladivostok

Vladivostok

The city is located in the southern extremity of Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, which is about 30 km long and approximately 12 km wide.The highest point is Mount Kholodilnik, the height of which is 257 m...

, in 1918. Kolchak was an absolute supporter of the Allied cause against Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, and initially hearing of the Bolshevik coup on November 7, 1917, he offered to enlist in the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

to continue the struggle. Initially, the British were inclined to accept Kolchak’s offer, and there were plans to send Kolchak to Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

(modern Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

), but London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

decided that Kolchak could do more for the Allied cause by overthrowing the Bolsheviks and bringing Russia back into the war on the Allied side. Reluctantly, Kolchak accepted the British suggestions and with a heavy sense of foreboding, Kolchak returned to Russia. Arriving in Omsk

Omsk

-History:The wooden fort of Omsk was erected in 1716 to protect the expanding Russian frontier along the Ishim and the Irtysh rivers against the Kyrgyz nomads of the Steppes...

, Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

, en route to enlisting with the Volunteer Army

Volunteer Army

The Volunteer Army was an anti-Bolshevik army in South Russia during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1920....

, he agreed to become a minister in the (White) Siberian Regional Government. Joining a fourteen man cabinet, he was a prestige figure; the government hoped to play on the respect he had with the Allies, especially the head of the British military mission, General Alfred Knox

Alfred Knox (general)

Major-General Sir Alfred William Fortescue Knox was a career British military officer and later a Conservative Party politician.Born in Ulster, he joined the British Army and was posted to India....

.

In November 1918, the unpopular regional government was overthrown in a military coup d'etat

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

. Kolchak had returned to Omsk on November 16 from an inspection tour. He was approached and refused to take power. The Socialist-Revolutionary

Socialist-Revolutionary Party

thumb|right|200px|Socialist-Revolutionary election poster, 1917. The caption in red reads "партия соц-рев" , short for Party of the Socialist Revolutionaries...

(SR) Directory leader and members were arrested on November 18 by a troop of Cossack

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

s under ataman

Ataman

Ataman was a commander title of the Ukrainian People's Army, Cossack, and haidamak leaders, who were in essence the Cossacks...

Krasilnikov. The remaining cabinet members met and voted for Kolchak to become the head of government with dictatorial powers. He was named Supreme Ruler (Verkhovnyi Pravitel), and he promoted himself to Admiral

Admiral

Admiral is the rank, or part of the name of the ranks, of the highest naval officers. It is usually considered a full admiral and above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet . It is usually abbreviated to "Adm" or "ADM"...

. The arrested SR politicians were expelled from Siberia and ended up in Europe.

He issued the following manifesto to the population:

The SR leaders in Russia denounced Kolchak and called for him to be killed. Their activities resulted in a small revolt in Omsk

Omsk

-History:The wooden fort of Omsk was erected in 1716 to protect the expanding Russian frontier along the Ishim and the Irtysh rivers against the Kyrgyz nomads of the Steppes...

on December 22, 1918, which was quickly put down by Cossacks and the Czechoslovak Legion, who summarily executed almost 500 rebels. The SRs opened negotiations with the Bolsheviks and in January 1919 the SR People's Army joined with the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

.

Kolchak pursued a policy of persecuting revolutionaries as well as Socialists of several factions. Kolchak’s government issued a decree on 3 December 1918 stating, “In order to preserve the system and rule of the Supreme Ruler, articles of the criminal code of Imperial Russia were revised, Articles 99 and 100 of which established capital punishment for assassination attempts on the Supreme Ruler and for attempting to overthrow the authorities. “Insults written, printed, and oral, are punishable by imprisonment under Article 103. Bureaucratic sabotage under Article 329 was punishable by hard labor from 15 to 20 years.

On April 11, 1919, the Kolchak's government adopted Regulation no. 428, “About the dangers of public order due to ties with the Bolshevik Revolt”. The legislation was published in the Omsk newspaper Omsk Gazette (no. 188 of 19 July 1919). It provided a term of five years of prison for “individuals considered a threat to the public order because of their ties in any way with the Bollshevik revolt.” In the case of unauthorized return from exile, there could be hard labor from 4 to 8 years. Articles 99-101 allowed the death penalty, forced labor and imprisonment, repression by military courts, and imposed no investigation commissions.

Kolchak acknowledged all of Russia's debts, returned factories and plants to their owners, granted concessions to foreign investors, dispersed trade unions, persecuted Marxists, and disbanded the soviets. Kolchak's agrarian policy was directed toward restoring private land ownership. The former Tsarist laws were restored. There was brutal repression committed by Kolchak's regime: in Ekaterinburg alone the Great Soviet Encyclopedia alleges that more than 25,000 people were shot or tortured to death. In March 1919 Kolchak himself demanded one of his generals to "follow the example of the Japanese who, in the Amur region, had exterminated the local population."

Sovietskaya Rossiya, an "official organ" of Soviet Bureau

Soviet Bureau

The Russian Soviet Government Bureau , sometimes known as the "Soviet Bureau," was an unofficial diplomatic organization established by the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in the United States during the Russian Civil War. The Soviet Bureau primarily functioned as a trade and...

established by Ludwig Martens

Ludwig Martens

Ludwig Christian Alexander Karl Martens was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician and engineer.-Early years:...

, quoted a Menshevik

Menshevik

The Mensheviks were a faction of the Russian revolutionary movement that emerged in 1904 after a dispute between Vladimir Lenin and Julius Martov, both members of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party. The dispute originated at the Second Congress of that party, ostensibly over minor issues...

organ Vsegda Vperyod alleging that Kolchak's men used mass floggings and razed entire villages to the ground with artillery fire. 4,000 peasants allegedly became victims of field courts and punitive expeditions and that all dwellings of rebels were burned down.

An excerpt from the order of the government of Yenisei county in Irkutsk province, General. S. Rozanov said:

“Those villages whose population meets troops with arms, burn down the villages and shoot the adult males without exception.

If hostages are taken in cases of resistance to government troops, shoot the hostages without mercy."

There was prominent underground resistance in the regions controlled by Kolchak's government. These partisans were especially strong in the provinces of Altai

Altai Krai

Altai Krai is a federal subject of Russia . It borders with, clockwise from the south, Kazakhstan, Novosibirsk and Kemerovo Oblasts, and the Altai Republic. The krai's administrative center is the city of Barnaul...

and Yeniseysk

Yeniseysk

Yeniseysk is a town in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, located on the Yenisei River. Population: 20,000 .Yeniseysk was founded in 1619 as a stockaded town—the first town on the Yenisei River. It played an important role in Russian colonization of East Siberia in the 17th–18th centuries...

. In the summer of 1919 partisans of Altai Region united to form the Western Siberian Peasants' Red Army (25,000 men). The Taseev Soviet Partisan Republic was founded south-east of Yeniseysk in early 1919. By the fall of 1919, Kolchak's rear was completely disintegrating. About 100,000 Siberian Communists seized vast regions from Kolchak's regime even before the approach of the Red Army. In February 1920, some 20,000 partisans took control of the Amur region

Amur Oblast

Amur Oblast is a federal subject of Russia , situated about east of Moscow on the banks of the Amur and Zeya Rivers. It shares its border with the Sakha Republic in the north, Khabarovsk Krai and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in the east, People's Republic of China in the south, and Zabaykalsky...

.

British left-wing historian Edward Hallett Carr

Edward Hallett Carr

Edward Hallett "Ted" Carr CBE was a liberal and later Marxist British historian, journalist and international relations theorist, and an opponent of empiricism within historiography....

wrote,

On the contrary, a former Chief of Staff

Chief of Staff

The title, chief of staff, identifies the leader of a complex organization, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a Principal Staff Officer , who is the coordinator of the supporting staff or a primary aide to an important individual, such as a president.In general, a chief of...

to Admiral Kolchak wrote,

Supreme Governor of Russia

Initially the White forces under his command had some success. Kolchak was unfamiliar with combat on land and gave the majority of the strategic planning to D.A. Lebedev, Paul J. Bubnar, and his staff. The northern army under the Russian Anatoly PepelyayevAnatoly Pepelyayev

Anatoly Nikolayevich Pepelyayev was a White Russian general who led the Siberian armies of Admiral Kolchak during the Russian Civil War. His elder brother Viktor Pepelyayev served as Prime Minister in Kolchak's government.-Trans-Siberian march:...

and the Czech Rudolf Gajda

Radola Gajda

Radola Gajda, born as Rudolf Geidl, was a Czech/Montenegrin military commander and politician.- Early years :...

seized Perm

Perm

Perm is a city and the administrative center of Perm Krai, Russia, located on the banks of the Kama River, in the European part of Russia near the Ural Mountains. From 1940 to 1957 it was named Molotov ....

in late December 1918 and after a pause other forces spread out from this strategic base. The plan was for three main advances – Gajda to take Archangel

Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk , formerly known as Archangel in English, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina River near its exit into the White Sea in the north of European Russia. The city spreads for over along the banks of the river...

, Khanzhin to capture Ufa

Ufa

-Demographics:Nationally, dominated by Russian , Bashkirs and Tatars . In addition, numerous are Ukrainians , Chuvash , Mari , Belarusians , Mordovians , Armenian , Germans , Jews , Azeris .-Government and administration:Local...

and the Cossack

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

s under Alexander Dutov

Alexander Dutov

Alexander Ilyich Dutov , one of the leaders of the Cossack counterrevolution in the Urals, Lieutenant General .Dutov was born in Kazalinsk...

to capture Samara

Samara, Russia

Samara , is the sixth largest city in Russia. It is situated in the southeastern part of European Russia at the confluence of the Volga and Samara Rivers. Samara is the administrative center of Samara Oblast. Population: . The metropolitan area of Samara-Tolyatti-Syzran within Samara Oblast...

and Saratov

Saratov

-Modern Saratov:The Saratov region is highly industrialized, due in part to the rich in natural and industrial resources of the area. The region is also one of the more important and largest cultural and scientific centres in Russia...

. Kolchak had put around 110,000 men into the field facing roughly 95,000 Bolshevik troops. Kolchak's good relations with General Alfred Knox meant that his forces were partly armed, munitioned and uniformed by the British (up to August 1919 the British spent an official $239 million aiding the Whites, although Churchill disputed this figure at the time as an "absurd exaggeration").

The White forces took Ufa

Ufa

-Demographics:Nationally, dominated by Russian , Bashkirs and Tatars . In addition, numerous are Ukrainians , Chuvash , Mari , Belarusians , Mordovians , Armenian , Germans , Jews , Azeris .-Government and administration:Local...

in March 1919 and pushed on from there to take Kazan

Kazan

Kazan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia. With a population of 1,143,546 , it is the eighth most populous city in Russia. Kazan lies at the confluence of the Volga and Kazanka Rivers in European Russia. In April 2009, the Russian Patent Office granted Kazan the...

and approach Samara on the Volga River

Volga River

The Volga is the largest river in Europe in terms of length, discharge, and watershed. It flows through central Russia, and is widely viewed as the national river of Russia. Out of the twenty largest cities of Russia, eleven, including the capital Moscow, are situated in the Volga's drainage...

. Anti-Communist risings in Simbirsk, Kazan

Kazan

Kazan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia. With a population of 1,143,546 , it is the eighth most populous city in Russia. Kazan lies at the confluence of the Volga and Kazanka Rivers in European Russia. In April 2009, the Russian Patent Office granted Kazan the...

, Viatka

Kirov, Kirov Oblast

Kirov , formerly known as Vyatka and Khlynov, is a city in northeastern European Russia, on the Vyatka River, and the administrative center of Kirov Oblast. Population: -History:...

, and Samara

Samara, Russia

Samara , is the sixth largest city in Russia. It is situated in the southeastern part of European Russia at the confluence of the Volga and Samara Rivers. Samara is the administrative center of Samara Oblast. Population: . The metropolitan area of Samara-Tolyatti-Syzran within Samara Oblast...

assisted their endeavours. The newly-formed Red Army proved unwilling to fight and retreated, allowing the Whites to advance to a line stretching from Glazov

Glazov

Glazov is a town located in the north of the Udmurt Republic, Russia along the Trans-Siberian Railway. Population: It was founded in the 16th century as a village; town status was granted to it in 1780. Olga Knipper, wife of the famous Russian writer Anton Chekhov, was born in Glazov. During the...

through Orenburg

Orenburg

Orenburg is a city on the Ural River and the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies southeast of Moscow, very close to the border with Kazakhstan. Population: 546,987 ; 549,361 ; Highest point: 154.4 m...

to Uralsk. Kolchak's territories covered over 300,000 km² and held around 7 million people. In April, the alarmed Bolshevik Central Executive Committee

All-Russian Central Executive Committee

All-Russian Central Executive Committee , was the highest legislative, administrative, and revising body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Although the All-Russian Congress of Soviets had supreme authority, in periods between its sessions its powers were passed to VTsIK...

made defeating Kolchak its top priority. But as the spring thaw arrived Kolchak's position degenerated – his armies had outrun their supply lines, they were exhausted, and the Red Army was pouring newly raised troops into the area.

Kolchak had also aroused the dislike of potential allies including the Czechoslovak Legion and the Polish 5th Rifle Division

Polish 5th Rifle Division

Polish 5th Siberian Rifle Division was a Polish military unit formed in 1919 in Russia during World War I. The division fought during the Polish-Bolshevik War, but as it was attached to the White Russian formations, it is considered to have fought more in the Russian Civil War...

. They withdrew from the conflict in October 1918 but remained a presence, their new leader Maurice Janin

Maurice Janin

Pierre-Thiébaut-Charles-Maurice Janin was a French general and military commander who was the chief of the French military mission in Siberia during the Russian civil war....

regarded Kolchak as an instrument of the British and was pro-SR. Kolchak could not count on Japanese aid either; the Japanese feared he would interfere with their occupation of Far Eastern Russia and refused him assistance, creating a 'buffer state

Buffer state

A buffer state is a country lying between two rival or potentially hostile greater powers, which by its sheer existence is thought to prevent conflict between them. Buffer states, when authentically independent, typically pursue a neutralist foreign policy, which distinguishes them from satellite...

' to the east of Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal is the world's oldest at 30 million years old and deepest lake with an average depth of 744.4 metres.Located in the south of the Russian region of Siberia, between Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Buryat Republic to the southeast, it is the most voluminous freshwater lake in the...

under Cossack control. The 7,000 or so American troops in Siberia were strictly neutral regarding "internal Russian affairs" and served only to maintain the operation of the Trans-Siberian railroad

Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway is a network of railways connecting Moscow with the Russian Far East and the Sea of Japan. It is the longest railway in the world...

in the Far East. The American commander, General William S. Graves

William S. Graves

Major General William Sidney Graves . The commander of American forces in Siberia during the Allied Intervention in Russia.-Biography:...

, personally disliked the Kolchak government, which he saw as Monarchist and autocratic, a view that was shared by the American President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

. As a result, both refused to grant him any aid.

Defeat and death

Chelyabinsk

Chelyabinsk is a city and the administrative center of Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, located in the northwestern side of the oblast, south of Yekaterinburg, just to the east of the Ural Mountains, on the Miass River. Population: -History:...

on July 25 and forcing the White forces to the north and south to fall back to avoid being isolated. The White forces re-established a line along the Tobol and the Ishim rivers to temporarily halt the Reds. They held that line until October, but the constant loss of men killed or wounded was beyond the White rate of replacement. Reinforced, the Reds broke through on the Tobol in mid-October and by November the White forces were falling back towards Omsk in a disorganised mass. The Reds were sufficiently confident to start redeploying some of their forces southwards to face Anton Denikin.

Kolchak also came under threat from other quarters: local opponents began to agitate and international support began to wane, with even the British turning more towards Denikin. Gajda

Radola Gajda

Radola Gajda, born as Rudolf Geidl, was a Czech/Montenegrin military commander and politician.- Early years :...

, dismissed from command of the northern army, staged an abortive coup in mid-November. Omsk was evacuated on November 14 and the Red Army took the city without any serious resistance, capturing large amounts of ammunition, almost 50,000 soldiers, and ten generals. As there was a continued flood of refugees eastwards, typhus

Typhus

Epidemic typhus is a form of typhus so named because the disease often causes epidemics following wars and natural disasters...

became a serious problem.

Kolchak had left Omsk on the 13th for Irkutsk

Irkutsk

Irkutsk is a city and the administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia, one of the largest cities in Siberia. Population: .-History:In 1652, Ivan Pokhabov built a zimovye near the site of Irkutsk for gold trading and for the collection of fur taxes from the Buryats. In 1661, Yakov Pokhabov...

along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Travelling a section of track controlled by the Czechoslovaks he was sidetracked and stopped; by December his train had only reached Nizhneudinsk. In late December Irkutsk fell under the control of a leftist group (including SRs) and formed the Political Centre

Political Centre (Russia)

Political Centre was an independent political group in Irkutsk during the Russian Civil War .Being established in November 1919, its leaning was leftist: SR and Menshevik. The target was to remove Aleksandr Kolchak from power. That's why the Political Centre members joined local Bolsheviks and on...

. One of their first actions was to dismiss Kolchak. When he heard of this on January 4, 1920, he announced his resignation, giving his office to Denikin and passing control of his remaining forces around Irkutsk to the ataman

Ataman

Ataman was a commander title of the Ukrainian People's Army, Cossack, and haidamak leaders, who were in essence the Cossacks...

, G. M. Semyonov. The transfer of power to Semyonov proved a particularly ill-considered move.

Vladimir Kappel

Vladimir Oskarovich Kappel was a White Russian military leader.During the First World War he was a Chief of the 347th Infantry Regiment's Staff and an officer in the 1st Army's Staff...

rushed toward Irkutsk while Kolchak was "investigated" before a commission of five men from January 21 to February 6. Despite the arrival of a contrary order from Moscow, Admiral Kolchak was summarily sentenced to death along with his Prime Minister, Viktor Pepelyayev

Viktor Pepelyayev

Viktor Nikolayevich Pepelyayev was a Russian politician associated with the White movement. Brother of Anatoly Pepelyayev....

.

Both prisoners were brought before a firing squad in the early morning of 7 February 1920. According to eyewitnesses, Kolchak was entirely calm and unafraid, "like and Englishman." The Admiral asked the commander of the firing squad, "Would you be so good as to get a message sent to my wife in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

to say that I bless my son?" The commander responded, "I'll see what can be done, if I don't forget about it."

A priest of the Russian Orthodox Church

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

then gave the last rites

Last Rites

The Last Rites are the very last prayers and ministrations given to many Christians before death. The last rites go by various names and include different practices in different Christian traditions...

to both men. The squad fired and both men fell. The bodies were kicked and prodded down an escarpment and dumped under the ice of the frozen Angara River

Angara River

The Angara River is a long river in Irkutsk Oblast and Krasnoyarsk Krai, south-east Siberia, Russia. It is the only river flowing out of Lake Baikal, and is the headwater tributary of the Yenisei River....

. When the White Army learned about the executions, the decision was made to withdraw farther east. The Great Siberian Ice March

Great Siberian Ice March

The Great Siberian Ice march was the winter retreat of Vladimir Kappel's White Russian Army in the course of the Russian Civil War in January–February 1920....

followed. The Red Army did not enter Irkutsk until March 7, and only then was the news of Kolchak's death officially released.

Legacy

Admiral Kolchak was not successful from the time of his taking the position of Supreme Ruler until his death, though it must be borne in mind that he operated under very difficult circumstances. As a military commander he was unable to make successful strategic plans or to manage to coordinate with other White Army generals such as Yudenich or DenikinAnton Ivanovich Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin was Lieutenant General of the Imperial Russian Army and one of the foremost generals of the White movement in the Russian Civil War.- Childhood :...

.

Kolchak failed to convince the potentially friendly states of Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, or the Baltic states

Baltic states

The term Baltic states refers to the Baltic territories which gained independence from the Russian Empire in the wake of World War I: primarily the contiguous trio of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania ; Finland also fell within the scope of the term after initially gaining independence in the 1920s.The...

to join with him against the Bolsheviks. He was unable to win diplomatic recognition from any nation in the world, even Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

(though the British did support him to some degree). He alienated the Czechoslovak Legion, which for a time was a powerful organized military force and very strongly anti-Bolshevik. As was mentioned above, the American commander, General Graves

William S. Graves

Major General William Sidney Graves . The commander of American forces in Siberia during the Allied Intervention in Russia.-Biography:...

, disliked Kolchak and refused to lend him any military aid at all.

After decades of being vilified by the Soviet government, Kolchak is now a controversial historic figure in post-Soviet Russia. The "For Faith and Fatherland

For Faith and Fatherland

For Faith and Fatherland is a nationalist, monarchist organization headed by Orthodox hieromonk Nikon Belavenets.-Sources:*Valeria Korchagina and Andrei Zolotov Jr. The St. Petersburg Times. 6 Nov 2001.* Alexander Verkhovsky Panorama...

" movement has attempted to rehabilitate

Rehabilitation (Soviet)

Rehabilitation in the context of the former Soviet Union, and the Post-Soviet states, was the restoration of a person who was criminally prosecuted without due basis, to the state of acquittal...

his reputation. However, two rehabilitation requests have been denied, by a regional military court in 1999 and by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation

Supreme Court of the Russian Federation

The Supreme Court of the Russian Federation is the court of last resort in Russian administrative law, civil law and criminal law cases. It also supervises the work of lower courts. Its predecessor is the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union....

in 2001. In 2004, the Constitutional Court

Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation

The Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation is a high court which is empowered to rule on whether or not certain laws or presidential decrees are in fact contrary to the Constitution of Russia...

of Russia returned the Kolchak case to the military court for another hearing.

Monuments dedicated to Kolchak were built in Saint Petersburg in 2002 and in Irkutsk in 2004, despite objections from some former Communist and left-wing politicians and former Soviet army veterans. There is also a Kolchak Island

Kolchak Island

Kolchak Island or Kolchaka Island , is an island in the Kara Sea located NE of the Shturmanov Peninsula, in an area of skerries south of the Nordenskiöld Archipelago. Compared to other large islands in the area it has a quite regular shape....