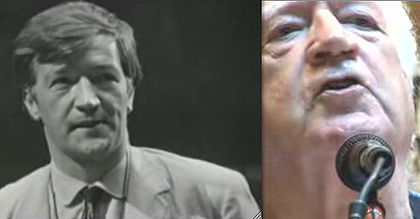

Adrian Mitchell

Encyclopedia

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

, he became a noted figure on the British anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism, which is defined as a "political doctrine advocating the principle of absolute rule: absolutism, autocracy, despotism, dictatorship, totalitarianism." Anti-authoritarians usually believe in full equality before the law and strong civil...

Left

Left-wing politics

In politics, Left, left-wing and leftist generally refer to support for social change to create a more egalitarian society...

. For almost half a century he was the foremost poet of the country's anti-Bomb movement. The critic Kenneth Tynan

Kenneth Tynan

Kenneth Peacock Tynan was an influential and often controversial English theatre critic and writer.-Early life:...

called him the British Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky was a Russian and Soviet poet and playwright, among the foremost representatives of early-20th century Russian Futurism.- Early life :...

.

Mitchell sought in his work to counteract the implications of his own assertion that, "Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people."

In a National Poetry Day poll in 2005 his poem "Human Beings" was voted the one most people would like to see launched into space. In 2002 he was nominated, semi-seriously, Britain's Shadow Poet Laureate

Poet Laureate

A poet laureate is a poet officially appointed by a government and is often expected to compose poems for state occasions and other government events...

. Mitchell was for some years poetry editor of the New Statesman

New Statesman

New Statesman is a British centre-left political and cultural magazine published weekly in London. Founded in 1913, and connected with leading members of the Fabian Society, the magazine reached a circulation peak in the late 1960s....

, and was the first to publish an interview with The Beatles

The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, active throughout the 1960s and one of the most commercially successful and critically acclaimed acts in the history of popular music. Formed in Liverpool, by 1962 the group consisted of John Lennon , Paul McCartney , George Harrison and Ringo Starr...

. His work for the Royal Shakespeare Company

Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs 700 staff and produces around 20 productions a year from its home in Stratford-upon-Avon and plays regularly in London, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and on tour across...

included Peter Brook

Peter Brook

Peter Stephen Paul Brook CH, CBE is an English theatre and film director and innovator, who has been based in France since the early 1970s.-Life:...

's US and the English version of Peter Weiss

Peter Weiss

Peter Ulrich Weiss was a German writer, painter, and artist of adopted Swedish nationality. He is particularly known for his plays Marat/Sade and The Investigation and his novel The Aesthetics of Resistance....

's Marat/Sade

Marat/Sade

The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade , almost invariably shortened to Marat/Sade, is a 1963 play by Peter Weiss...

.

Ever inspired by the example of his own favourite poet and precursor William Blake

William Blake

William Blake was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age...

, about whom he wrote the acclaimed Tyger for the National Theatre

Royal National Theatre

The Royal National Theatre in London is one of the United Kingdom's two most prominent publicly funded theatre companies, alongside the Royal Shakespeare Company...

, his often angry output swirled from anarchistic

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

anti-war

Anti-war

An anti-war movement is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conflicts. Many...

satire

Satire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

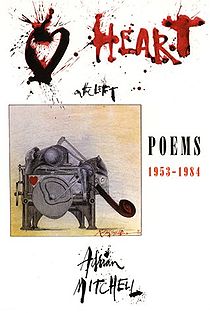

, through love poetry to, increasingly, stories and poems for children. He also wrote librettos. The Poetry Archive identified his creative yield as hugely prolific.

The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

said that Mitchell's had been a "forthright voice often laced with tenderness." His poems

Poetry

Poetry is a form of literary art in which language is used for its aesthetic and evocative qualities in addition to, or in lieu of, its apparent meaning...

on such topics as nuclear war, Vietnam

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

, prison

Prison

A prison is a place in which people are physically confined and, usually, deprived of a range of personal freedoms. Imprisonment or incarceration is a legal penalty that may be imposed by the state for the commission of a crime...

s and racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

had become "part of the folklore of the Left. His work was often read and sung at demonstrations and rallies

Demonstration (people)

A demonstration or street protest is action by a mass group or collection of groups of people in favor of a political or other cause; it normally consists of walking in a mass march formation and either beginning with or meeting at a designated endpoint, or rally, to hear speakers.Actions such as...

."

Early life and career

Adrian Mitchell was born near Hampstead HeathHampstead Heath

Hampstead Heath is a large, ancient London park, covering . This grassy public space sits astride a sandy ridge, one of the highest points in London, running from Hampstead to Highgate, which rests on a band of London clay...

, North London

North London

North London is the northern part of London, England. It is an imprecise description and the area it covers is defined differently for a range of purposes. Common to these definitions is that it includes districts located north of the River Thames and is used in comparison with South...

. His mother, Kathleen Fabian, was a Fröbel-trained nursery school

Nursery school

A nursery school is a school for children between the ages of one and five years, staffed by suitably qualified and other professionals who encourage and supervise educational play rather than simply providing childcare...

teacher and his father Jock Mitchell, a research chemist

Chemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

from Cupar

Cupar

Cupar is a town and former royal burgh in Fife, Scotland. The town is situated between Dundee and the New Town of Glenrothes.According to a recent population estimate , Cupar had a population around 8,980 making the town the ninth largest settlement in Fife.-History:The town is believed to have...

in Fife

Fife

Fife is a council area and former county of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries to Perth and Kinross and Clackmannanshire...

. He was educated at Monkton Combe School

Monkton Combe School

Monkton Combe School is an independent boarding and day school of the British public school tradition, near Bath, England. The Senior School is located in the village of Monkton Combe, while the Prep School, Pre-Prep and Nursery are in Combe Down on the southern outskirts of Bath...

, "a school full of bullies, whose playground he characterised as 'the killing ground'". He then went to Greenways at Ashton Gifford House

Ashton Gifford House

Ashton Gifford House is a Grade II listed building in the hamlet of Ashton Gifford, part of the civil parish of Codford in the English county of Wiltshire. The house was built during the early 19th century, following the precepts of Georgian architecture, and its estate eventually included all of...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire

Wiltshire is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. It contains the unitary authority of Swindon and covers...

, run at the time by a friend of his mother. This, said Mitchell, was "a school in Heaven

Heaven

Heaven, the Heavens or Seven Heavens, is a common religious cosmological or metaphysical term for the physical or transcendent place from which heavenly beings originate, are enthroned or inhabit...

, where my first play, The Animals' Brains Trust, was staged when I was nine to my great satisfaction."

His schooling was completed as a boarder at Dauntsey's School

Dauntsey's School

Dauntsey's School is a co-educational independent day and boarding school in the village of West Lavington, Wiltshire, England. The School was founded in 1542, in accordance with the will of William Dauntesey, a master of the Worshipful Company of Mercers....

, after which he did his National Service

National service

National service is a common name for mandatory government service programmes . The term became common British usage during and for some years following the Second World War. Many young people spent one or more years in such programmes...

in the RAF. He commented that this "confirmed (his) natural pacificism". He went on to study English at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church or house of Christ, and thus sometimes known as The House), is one of the largest constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England...

, where he was taught by J.R.R. Tolkien’s son. He became chairman of the university's poetry society and the literary editor of Isis magazine

Isis magazine

The Isis Magazine was established at Oxford University in 1892 . Traditionally a rival to the student newspaper Cherwell, it was finally acquired by the latter's publishing house, OSPL, in the late 1990s...

. On graduating Mitchell got a job as a reporter on the Oxford Mail

Oxford Mail

Oxford Mail is a daily tabloid newspaper in Oxford, England owned by Newsquest. It is published six days a week. It is a sister paper to the weekly tabloid The Oxford Times.-History:...

and, later, at the Evening Standard

Evening Standard

The Evening Standard, now styled the London Evening Standard, is a free local daily newspaper, published Monday–Friday in tabloid format in London. It is the dominant regional evening paper for London and the surrounding area, with coverage of national and international news and City of London...

in London.

"Inheriting enough money to live on for a year, I wrote my first novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

and my first TV play. Soon afterwards I became a freelance journalist, writing about pop music for the Daily Mail

Daily Mail

The Daily Mail is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust. First published in 1896 by Lord Northcliffe, it is the United Kingdom's second biggest-selling daily newspaper after The Sun. Its sister paper The Mail on Sunday was launched in 1982...

and TV for the pre-tabloid Sun

The Sun (newspaper)

The Sun is a daily national tabloid newspaper published in the United Kingdom and owned by News Corporation. Sister editions are published in Glasgow and Dublin...

and the Sunday Times. I quit journalism in the mid-Sixties and since then have been a free-falling poet, playwright and writer of stories."

Career

Mitchell gave frequent public readings, particularly for left-wing causes. SatireSatire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

was his speciality. Commissioned to write a poem about Prince Charles

Charles, Prince of Wales

Prince Charles, Prince of Wales is the heir apparent and eldest son of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Since 1958 his major title has been His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales. In Scotland he is additionally known as The Duke of Rothesay...

and his special relationship (as Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (disambiguation)

Prince of Wales is the title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom. It originated as the title of independent princes of Wales in the 12th and 13th centuries.* It is currently used by Charles, Prince of Wales....

) with the people of Wales, his measured response was short and to the point: "Royalty

House of Windsor

The House of Windsor is the royal house of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded by King George V by royal proclamation on the 17 July 1917, when he changed the name of his family from the German Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the English Windsor, due to the anti-German sentiment in the United Kingdom...

is a neurosis

Neurosis

Neurosis is a class of functional mental disorders involving distress but neither delusions nor hallucinations, whereby behavior is not outside socially acceptable norms. It is also known as psychoneurosis or neurotic disorder, and thus those suffering from it are said to be neurotic...

. Get well soon."

- My brain socialist

- My heart anarchist

- My eyes pacifist

- My blood revolutionary

Mitchell was in the habit of stipulating in any preface to his collections: "None of the work in this book is to be used in connection with any examination whatsoever." His best-known poem, "To Whom It May Concern", was his bitterly sarcastic reaction to the televised horrors of the Vietnam War. The poem begins,

- I was run over by the truth one day.

- Ever since the accident I’ve walked this way

- So stick my legs in plaster

- Tell me lies about Vietnam

He first read it to thousands of nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament refers to both the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated....

protesters who, having marched through central London on CND's first new format one-day Easter March, finally crammed into Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square is a public space and tourist attraction in central London, England, United Kingdom. At its centre is Nelson's Column, which is guarded by four lion statues at its base. There are a number of statues and sculptures in the square, with one plinth displaying changing pieces of...

on the afternoon of Easter Day 1964. As Mitchell delivered his lines from the pavement above in front of the National Gallery, angry demonstrators in the square below scuffled with police.

He was later responsible for the well-respected stage adaptation

Adaptations of The Chronicles of Narnia

The Chronicles of Narnia is a series of seven fantasy novels for children written by C. S. Lewis. It is considered a classic of children's literature and is the author's best-known work, having sold over 100 million copies in 47 languages...

of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a fantasy novel for children by C. S. Lewis. Published in 1950 and set circa 1940, it is the first-published book of The Chronicles of Narnia and is the best known book of the series. Although it was written and published first, it is second in the series'...

, a production of the Royal Shakespeare Company

Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs 700 staff and produces around 20 productions a year from its home in Stratford-upon-Avon and plays regularly in London, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and on tour across...

that premiered in November 1998.

Over the years he updated the poem to take into account recent events.

"He never let up. Most calls—'Can you do this one, Adrian?'—were answered, 'Sure, I'll be there.' His reading of "Tell Me Lies" at a City Hall benefit just before the 2003 invasion of Iraq was electrifying. Of course, he couldn't stop that war, but he performed as if he could."

One Remembrance Sunday he laid the Peace Pledge Union

Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union is a British pacifist non-governmental organization. It is open to everyone who can sign the PPU pledge: "I renounce war, and am therefore determined not to support any kind of war...

's White Poppy

White Poppy

thumb|right|300px|Artificial poppies placed as [[Anzac Day]] tributes on a [[cenotaph]] in [[New Zealand]]; mostly [[red poppy#Symbol|red poppies]] marketed by the [[Royal New Zealand Returned and Services' Association]], with a lone [[White Poppy]]...

wreath on the Cenotaph

Cenotaph

A cenotaph is an "empty tomb" or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been interred elsewhere. The word derives from the Greek κενοτάφιον = kenotaphion...

in Whitehall. On one International Conscientious Objectors' Day he read a poem at the ceremony at the Conscientious Objectors' Commemorative Stone in Tavistock Square

Tavistock Square

Tavistock Square is a public square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden with a fine garden.-Public art:The centre-piece of the gardens is a statue of Mahatma Gandhi, which was installed in 1968....

in London.

Fellow writers could be effusive in their tributes. John Berger

John Berger

John Peter Berger is an English art critic, novelist, painter and author. His novel G. won the 1972 Booker Prize, and his essay on art criticism Ways of Seeing, written as an accompaniment to a BBC series, is often used as a university text.-Education:Born in Hackney, London, England, Berger was...

said that, "Against the present British state he opposes a kind of revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

ary populism

Populism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

, bawdiness, wit

Wit

Wit is a form of intellectual humour, and a wit is someone skilled in making witty remarks. Forms of wit include the quip and repartee.-Forms of wit:...

and the tenderness sometimes to be found between animals." Angela Carter

Angela Carter

Angela Carter was an English novelist and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism, and picaresque works...

once wrote that he was "a joyous, acrid and demotic tumbling lyricist Pied Piper, determinedly singing us away from catastrophe." Ted Hughes

Ted Hughes

Edward James Hughes OM , more commonly known as Ted Hughes, was an English poet and children's writer. Critics routinely rank him as one of the best poets of his generation. Hughes was British Poet Laureate from 1984 until his death.Hughes was married to American poet Sylvia Plath, from 1956 until...

: "In the world of verse for children, nobody has produced more surprising verse or more genuinely inspired fun than Adrian Mitchell."

Mitchell died at the age of 76 in a North London hospital from a suspected heart attack

Myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction , commonly known as a heart attack, results from the interruption of blood supply to a part of the heart, causing heart cells to die...

. For two months he had been suffering from pneumonia

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung—especially affecting the microscopic air sacs —associated with fever, chest symptoms, and a lack of air space on a chest X-ray. Pneumonia is typically caused by an infection but there are a number of other causes...

. Two days earlier he had completed what turned out to be his last poem, "My Literary Career So Far". He intended it as a Christmas

Christmas

Christmas or Christmas Day is an annual holiday generally celebrated on December 25 by billions of people around the world. It is a Christian feast that commemorates the birth of Jesus Christ, liturgically closing the Advent season and initiating the season of Christmastide, which lasts twelve days...

gift to "all the friends, family and animals he loved".

"Adrian", said fellow-poet Michael Rosen

Michael Rosen

Michael Wayne Rosen is a broadcaster, children's novelist and poet and the author of 140 books. He was appointed as the fifth Children's Laureate in June 2007, succeeding Jacqueline Wilson, and held this honour until 2009....

, "was a socialist and a pacifist who believed, like William Blake, that everything human was holy. That's to say he celebrated a love of life with the same fervour that he attacked those who crushed life. He did this through his poetry, his plays, his song lyrics and his own performances. Through this huge body of work, he was able to raise the spirits of his audiences, in turn exciting, inspiring, saddening and enthusing them ... He has sung, chanted, whispered and shouted his poems in every kind of place imaginable, urging us to love our lives, love our minds and bodies and to fight against tyranny, oppression

Oppression

Oppression is the exercise of authority or power in a burdensome, cruel, or unjust manner. It can also be defined as an act or instance of oppressing, the state of being oppressed, and the feeling of being heavily burdened, mentally or physically, by troubles, adverse conditions, and...

and exploitation

Exploitation

This article discusses the term exploitation in the meaning of using something in an unjust or cruel manner.- As unjust benefit :In political economy, economics, and sociology, exploitation involves a persistent social relationship in which certain persons are being mistreated or unfairly used for...

."

Family

Mitchell is survived by his wife, the actress Celia Hewitt, whose bookshop, Ripping Yarns, is in Highgate, and their two daughters Sasha and Beattie. He also has two sons and a daughter from his previous marriage to Maureen Bush: Briony, Alistair and Danny—. There are nine grandchildren: Robin, Arthur, Charlotte, Natasha, Zoe, Caitlin, Annie, Lola and Lilly.Awards

- 1961 Eric Gregory AwardEric Gregory AwardThe Eric Gregory Award is given by the Society of Authors to British poets under 30 on submission. The awards are up to a sum value of £24000 annually....

- 1966 PEN Translation PrizePEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation PrizeThe PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Prize is an annual award given to outstanding translations into the English language. It has been presented annually by PEN American Center and the Book of the Month Club since 1963....

- 1971 Tokyo Festival Television Film Award

- 2005 CLPE Poetry Award (shortlist) for Daft as a Doughnut

External links

- Adrian Mitchell's homepage

- The Poetry Archive

- The Argotist interview

- Adrian Mitchell's poem "Victor Jara," with music by Arlo Guthrie, performed by Guthrie and his band Shendandoah in 1978

Obituaries

- To the memory of Adrian Mitchell World Socialist web site

- The Independent obituary by Michael HorovitzMichael HorovitzMichael Horovitz is an English poet, artist and translator.-Life and career:Michael Horovitz was the youngest of ten children who were brought to England from Nazi Germany by their parents, both of whom were part of a network of European-rabbinical families...

- The Guardian obituary by Michael Kustow

- Daily Telegraph obituary

- Times obituary

- New York Times

- Camden New Journal

- Michael Rosen: Passionate poet unafraid of the big stuff