1810s

Encyclopedia

The 1810s decade ran from January 1, 1810, to December 31, 1819.

and to besieged Cadiz

. Napoleon married Marie-Louise

, an Austrian Archduchess, with the aim of ensuring a more stable alliance with Austria and of providing the Emperor with an heir. As well as the French Empire, Napoleon controlled the Swiss Confederation, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Italy. Territories allied with the French included: the Kingdom of Spain, the Kingdom of Westphalia

, the Kingdom of Naples, the Principality

of Lucca and Piombino, and Napoleon's former enemies, Prussia and Austria. Denmark–Norway

also allied with France in opposition to Great Britain and Sweden in the Gunboat War

.

The French invasion of Russia

of 1812 was a turning point, which reduced the French

and allied invasion forces (the Grande Armée) to a tiny fraction of their initial strength and triggered a major shift in European politics, as it dramatically weakened the previously dominant French position on the continent. After the disastrous invasion of Russia, a coalition of Austria

, Prussia

, Russia

, Sweden, the United Kingdom

, and a number of German States

, and the rebels in Spain

and Portugal

united to battle France in the War of the Sixth Coalition

. Two-and-a-half million troops fought in the conflict and the total dead amounted to as many as two million. This era included the battles of Smolensk

, Borodino

, Lützen

, Bautzen

, and the Dresden

. It also included the epic Battle of Leipzig

in October, 1813 (also known as the Battle of Nations), which was the largest battle of the Napoleonic wars, which drove Napoleon out of Germany.

The final stage of the War of the Sixth Coalition, the defense of France in 1814, saw the French Emperor temporarily repulse the vastly superior armies in the Six Days Campaign

The final stage of the War of the Sixth Coalition, the defense of France in 1814, saw the French Emperor temporarily repulse the vastly superior armies in the Six Days Campaign

. Ultimately, the Allies occupied Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate and restoring the Bourbons

. Napoleon was exiled to Elba

. Also in 1814, Denmark–Norway was defeated by Great Britain and Sweden and had to cede the territory of mainland Norway to the King of Sweden at the Treaty of Kiel

.

Napoleon shortly returned from exile, landing in France on March 1, 1815, marking the War of the Seventh Coalition, heading toward Paris while the Congress of Vienna

was sitting. On March 13, seven days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw; four days later the United Kingdom

, Russia

, Austria

and Prussia

, members of the Seventh Coalition, bound themselves to put 150,000 men each into the field to end his rule. This set the stage for the last conflict in the Napoleonic Wars

, the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo

, the restoration of the French monarchy for the second time and the permanent exile of Napoleon to the distant island of Saint Helena

, where he died in May 1821.

" ensued, driven by an emergent Spanish nationalism

. Already in 1810, the Caracas

and Buenos Aires

juntas declared their independence from the Bonapartist government in Spain and sent ambassadors to the United Kingdom. The British blockade

against Spain had also moved most of the Latin American colonies out of the Spanish economic sphere and into the British sphere, with whom extensive trade relations were developed. The remaining Spanish colonies had operated with virtual independence from Madrid after their pronouncement against Joseph Bonaparte.

The Spanish government in exile (Cádiz Cortes

) created the first modern Spanish constitution

. Even so, agreements made at the Congress of Vienna

(where Spain was represented by Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador

) would cement international support for the old, absolutist

regime in Spain.

King Ferdinand VII, who assumed the throne after Napoleon was driven out of Spain, refused to agree to the liberal

Spanish Constitution of 1812

on his accession to the throne in 1814. The Spanish Empire

in the New World had largely supported the cause of Ferdinand VII over the Bonapartist pretender to the throne in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars

. When Ferdinand's rule was restored, these juntas were cautious of abandoning their autonomy, and an alliance between local elites, merchant interests, nationalists, and liberals opposed to the abrogation of the Constitution of 1812 rose up against the Spanish in the New World.

The arrival of Spanish forces in the American colonies began in 1814, and was briefly successful in restoring central control over large parts of the Empire. Simón Bolívar

The arrival of Spanish forces in the American colonies began in 1814, and was briefly successful in restoring central control over large parts of the Empire. Simón Bolívar

, the leader of revolutionary forces in New Granada

, was briefly forced into exile in British-controlled Jamaica

, and independent Haiti

. In 1816, however, Bolivar found enough popular support that he was able to return to South America, and in a daring march from Venezuela to New Granada (Colombia

), he defeated Spanish forces at the Battle of Boyacá

in 1819, ending Spanish rule in Colombia. Venezuela

was liberated June 24, 1821 when Bolivar destroyed the Spanish army on the fields of Carabobo on the Battle of Carabobo. Argentina

declared its independence in 1816 (though it had been operating with virtual independence as a British client since 1807 after successfully resisting a British invasion). Chile

was retaken by Spain in 1814, but lost permanently in 1817 when an army under José de San Martín

, for the first time in history, crossed the Andes Mountains from Argentina to Chile, and went on to defeat Spanish royalist forces at the Battle of Chacabuco

in 1817.

Spain would also lose Florida

to the United States during this decade. First, in 1810, the Republic of West Florida

declared its independence from Spain, and was quickly annexed by the United States. Later, in 1818, the United States invaded Florida, resulting in the Adams-Onís Treaty

, wherein Spain ceded the rest of Florida to the United States.

In 1820, Mexico

, Peru

, Ecuador

, and Central America

still remained under Spanish control. Although Mexico

had been in revolt in 1811 under Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, resistance to Spanish rule had largely been confined to small guerrilla

bands in the countryside. King Ferdinand was still dissatisfied with the loss of so much of the Empire and resolved to retake it. A large expedition was assembled in Cadiz

with the aim of reconquest. However, Ferdinand's plans would be disrupted by Liberal Revolution, and Ferdinand was eventually forced to give up all of the New World colonies, except for Cuba

and Puerto Rico

.

in the War of 1812

. The U.S. reasons for war included the humiliation in the "Chesapeake incident" of 1807

, continued British impressment

of American sailors into the Royal Navy

, restrictions on trade with France, and arming hostile American Indians in Ohio and the western territories. United States President James Madison

signed a declaration of war on June 18, 1812.

The United States conducted two failed invasion attempts in 1812, first by General William Hull

across the Detroit River

into what is now Windsor, Ontario

, and a second offensive at the Niagara peninsula

. A major American success came in 1813, when the American Navy destroyed the British fleet on Lake Erie, and forced the British and their American Indian allies to retreat back toward Niagara. They were intercepted and destroyed by General William Henry Harrison

at the Battle of the Thames

in October 1813. Tecumseh

, the leader of the tribal confederation, was killed, and his Indian coalition disintegrated.

At sea, the powerful Royal Navy

blockaded much of the coastline, conducting frequent raids. The most famous episode was a series of British raids on the shores of Chesapeake Bay

, including an attack on Washington that resulted in the British burning of the White House

, the Capitol

, the Navy Yard

, and other public buildings, in the "Burning of Washington

" in 1814.

Once Napoleon was defeated in 1814, France and Britain became allies and Britain ended the trade restrictions and the impressment of American sailors. Running out of reasons for war and stuck in a military stalemate, the two countries signed the Treaty of Ghent

on December 24, 1814. News of the peace treaty took two months to reach the U.S., during which fighting continued. In this interim, the British made one last major invasion, attempting to capture New Orleans, but were decisively defeated with very heavy losses by General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans

in January 1815. The ending of the war opened a long era of peaceful relations between the United States and the British Empire.

and Imperial Russia, and was well underway at the beginning of the decade. In 1810, the Persians scaled up their efforts late in the war, declaring a holy war on Imperial Russia. However, Russia's superior technology and tactics ensured a series of strategic victories. Even when the French were in occupation of the Russian capital Moscow, Russian forces in the south were not recalled but continued their offensive against Persia, culminating in Pyotr Kotlyarevsky

's victories at Aslanduz

and Lenkoran, in 1812 and 1813 respectively. Upon the Persian surrender, the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan ceded the vast majority of the previously disputed territories to Imperial Russia. This led to the region's once-powerful khans

being decimated and forced to pay homage to Russia.

throughout much of the continent, resulting in many states adopting the Napoleonic code

. Largely as a reaction to the radicalism of the French Revolution

, the victorious powers of the Napoleonic Wars

resolved to suppress liberalism and nationalism

, and revert largely to the status quo

of Europe prior to 1789.

The result was the Concert of Europe

The result was the Concert of Europe

, also known as the "Congress System". It was the balance of power

that existed in Europe from 1815 until the early 20th century. Its founding members were the United Kingdom

, Austrian Empire

, Russian Empire

and Kingdom of Prussia

, the members of the Quadruple Alliance

responsible for the downfall of the First French Empire

; in time France became established as a fifth member of the concert. At first, the leading personalities of the system were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh

, Austrian chancellor Klemens Wenzel, Prince von Metternich and Tsar

Alexander I

of Russia.

The Kingdom of Prussia

, Austrian Empire

and Russian Empire

formed the Holy Alliance

with the expressed intent of preserving Christian

social values and traditional monarchism

. Every member of the coalition promptly joined the Alliance, save for the United Kingdom

.

Among the meetings of the Powers in the latter part of the 1810s were the Congresses of Vienna

(1814–1815), Aix-la-Chappelle

(1818), and Carlsbad

(1819).

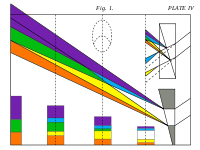

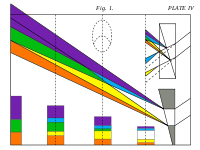

The 1810s continued a trend of increasing commercial viability of steamboat

The 1810s continued a trend of increasing commercial viability of steamboat

s in North America, following the early success of Robert Fulton

and others in the preceding years. In 1811 the first in a continuously operating line of river steamboats left the dock at Pittsburgh to steam down the Ohio River

to the Mississippi

and on to New Orleans. Inventor John Stevens

' boat, the Juliana, began operation as the first steam

-powered ferry

October 11, 1811, with service between New York

, and Hoboken, New Jersey

. John Molson

's PS Accommodation

was the first steamboat on the St. Lawrence and in Canada. Unlike Fulton, Molson did not show a profit. Molson had also two paddle steamboats "Swiftsure" of 1811 and "Malsham" of 1813 with engines by B&W. The experience of these vessels, especially that they could now offer a regular service, being independent of wind and weather, helped make the new system of propulsion commercially viable, and as a result its application to the more open waters of the Great Lakes

was next considered. That idea went on hiatus due to the War of 1812

.

In a 25-day trip in 1815, the Enterprise

further demonstrated the commercial potential of the steamboat with a 2,200-mile voyage from New Orleans to Pittsburgh. In 1817, a consortium in Sackets Harbor, New York

funded the construction of the first US steamboat, Ontario, to run on Lake Ontario

and the Great Lakes

, beginning the growth of lake commercial and passenger traffic.

The first commercially successful steamboat in Europe, Henry Bell's Comet

of 1812, started a rapid expansion of steam services on the Firth of Clyde

, and within four years a steamer service was in operation on the inland Loch Lomond

, a forerunner of the lake steamers still gracing Swiss lakes. On the Clyde itself, within ten years of Comet's start in 1812 there were nearly fifty steamers, and services had started across the Irish Sea

to Belfast

and on many British estuaries. P.S."Thames", ex "Argyle" was the first sea-going steamer in Europe, having steamed from Glasgow to London in May 1815. P.S."Tug", the first tugboat, was launched by the Woods Brothers, Port Glasgow, on November 5, 1817; in the summer of 1817 she was the first steamboat to travel round the North of Scotland to the East Coast.

The first steamship credited with crossing the Atlantic Ocean between North America and Europe was the American ship SS Savannah

The first steamship credited with crossing the Atlantic Ocean between North America and Europe was the American ship SS Savannah

, though she was actually a hybrid between a steamship and a sailing ship. The SS Savannah left the port of Savannah, Georgia

, on May 22, 1819, arriving in Liverpool

, England, on June 20, 1819; her steam engine having been in use for part of the time on 18 days (estimates vary from 8 to 80 hours).

, When We Two Parted, and So, we'll go no more a roving

, in addition to the narrative

poems Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

and Don Juan

.

Other events in literature:

Napoleonic Wars

In 1810, the French Empire reached its greatest extent. On the continent, the British and Portuguese remained restricted to the area around LisbonLisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

and to besieged Cadiz

Siege of Cádiz

The Siege of Cádiz was a siege of the large Spanish naval base of Cádiz by a French army from February 5, 1810 to August 24, 1812 during the Peninsular War. Following the occupation of Madrid on March 23, 1808, Cádiz became the Spanish seat of power, and was targeted by 60,000 French troops under...

. Napoleon married Marie-Louise

Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma

Marie Louise of Austria was the second wife of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French and later Duchess of Parma...

, an Austrian Archduchess, with the aim of ensuring a more stable alliance with Austria and of providing the Emperor with an heir. As well as the French Empire, Napoleon controlled the Swiss Confederation, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Italy. Territories allied with the French included: the Kingdom of Spain, the Kingdom of Westphalia

Kingdom of Westphalia

The Kingdom of Westphalia was a new country of 2.6 million Germans that existed from 1807-1813. It included of territory in Hesse and other parts of present-day Germany. While formally independent, it was a vassal state of the First French Empire, ruled by Napoleon's brother Jérôme Bonaparte...

, the Kingdom of Naples, the Principality

Principality

A principality is a monarchical feudatory or sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a monarch with the title of prince or princess, or by a monarch with another title within the generic use of the term prince....

of Lucca and Piombino, and Napoleon's former enemies, Prussia and Austria. Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway is the historiographical name for a former political entity consisting of the kingdoms of Denmark and Norway, including the originally Norwegian dependencies of Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands...

also allied with France in opposition to Great Britain and Sweden in the Gunboat War

Gunboat War

The Gunboat War was the naval conflict between Denmark–Norway and the British Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. The war's name is derived from the Danish tactic of employing small gunboats against the conventional Royal Navy...

.

The French invasion of Russia

French invasion of Russia

The French invasion of Russia of 1812 was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. It reduced the French and allied invasion forces to a tiny fraction of their initial strength and triggered a major shift in European politics as it dramatically weakened French hegemony in Europe...

of 1812 was a turning point, which reduced the French

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

and allied invasion forces (the Grande Armée) to a tiny fraction of their initial strength and triggered a major shift in European politics, as it dramatically weakened the previously dominant French position on the continent. After the disastrous invasion of Russia, a coalition of Austria

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

, Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, Sweden, the United Kingdom

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

, and a number of German States

Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederation of the Rhine was a confederation of client states of the First French Empire. It was formed initially from 16 German states by Napoleon after he defeated Austria's Francis II and Russia's Alexander I in the Battle of Austerlitz. The Treaty of Pressburg, in effect, led to the...

, and the rebels in Spain

Spain under the Restoration

The Restoration was the name given to the period that began on December 29, 1874 after the First Spanish Republic ended with the restoration of Alfonso XII to the throne after a coup d'état by Martinez Campos, and ended on April 14, 1931 with the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic.After...

and Portugal

Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal was Portugal's general designation under the monarchy. The kingdom was located in the west of the Iberian Peninsula, Europe and existed from 1139 to 1910...

united to battle France in the War of the Sixth Coalition

War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition , a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and a number of German States finally defeated France and drove Napoleon Bonaparte into exile on Elba. After Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, the continental powers...

. Two-and-a-half million troops fought in the conflict and the total dead amounted to as many as two million. This era included the battles of Smolensk

Battle of Smolensk (1812)

The Battle of Smolensk, the first major battle of the French invasion of Russia took place on August 16–18, 1812, between 175,000 men of the Grande Armée under Napoleon Bonaparte and 130,000 Russians under Barclay de Tolly, though only about 50,000 and 60,000 respectively were actually engaged...

, Borodino

Battle of Borodino

The Battle of Borodino , fought on September 7, 1812, was the largest and bloodiest single-day action of the French invasion of Russia and all Napoleonic Wars, involving more than 250,000 troops and resulting in at least 70,000 casualties...

, Lützen

Battle of Lützen (1813)

In the Battle of Lützen , Napoleon I of France lured a combined Prussian and Russian force into a trap, halting the advances of the Sixth Coalition after his devastating losses in Russia. The Russian commander, Prince Peter Wittgenstein, attempting to undo Napoleon's capture of Leipzig, attacked...

, Bautzen

Battle of Bautzen

In the Battle of Bautzen a combined Russian/Prussian army was pushed back by Napoleon, but escaped destruction, some sources claim, because Michel Ney failed to block their retreat...

, and the Dresden

Battle of Dresden

The Battle of Dresden was fought on 26–27 August 1813 around Dresden, Germany, resulting in a French victory under Napoleon I against forces of the Sixth Coalition of Austrians, Russians and Prussians under Field Marshal Schwartzenberg. However, Napoleon's victory was not as complete as it could...

. It also included the epic Battle of Leipzig

Battle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig or Battle of the Nations, on 16–19 October 1813, was fought by the coalition armies of Russia, Prussia, Austria and Sweden against the French army of Napoleon. Napoleon's army also contained Polish and Italian troops as well as Germans from the Confederation of the Rhine...

in October, 1813 (also known as the Battle of Nations), which was the largest battle of the Napoleonic wars, which drove Napoleon out of Germany.

Six Days Campaign

The Six Days Campaign was a final series of victories by the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte as the Sixth Coalition closed in on Paris....

. Ultimately, the Allies occupied Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate and restoring the Bourbons

Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration is the name given to the period following the successive events of the French Revolution , the end of the First Republic , and then the forcible end of the First French Empire under Napoleon – when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the...

. Napoleon was exiled to Elba

Elba

Elba is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino. The largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago, Elba is also part of the National Park of the Tuscan Archipelago and the third largest island in Italy after Sicily and Sardinia...

. Also in 1814, Denmark–Norway was defeated by Great Britain and Sweden and had to cede the territory of mainland Norway to the King of Sweden at the Treaty of Kiel

Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel or Peace of Kiel was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 in Kiel...

.

Napoleon shortly returned from exile, landing in France on March 1, 1815, marking the War of the Seventh Coalition, heading toward Paris while the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

was sitting. On March 13, seven days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw; four days later the United Kingdom

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

, Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, Austria

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

and Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, members of the Seventh Coalition, bound themselves to put 150,000 men each into the field to end his rule. This set the stage for the last conflict in the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

, the restoration of the French monarchy for the second time and the permanent exile of Napoleon to the distant island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena

Saint Helena , named after St Helena of Constantinople, is an island of volcanic origin in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha which also includes Ascension Island and the islands of Tristan da Cunha...

, where he died in May 1821.

Spanish American wars of independence

Spain in the 1810s was a country in turmoil. Occupied by Napoleon from 1808 to 1814, a massively destructive "war of independencePeninsular War

The Peninsular War was a war between France and the allied powers of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when French and Spanish armies crossed Spain and invaded Portugal in 1807. Then, in 1808, France turned on its...

" ensued, driven by an emergent Spanish nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

. Already in 1810, the Caracas

Caracas

Caracas , officially Santiago de León de Caracas, is the capital and largest city of Venezuela; natives or residents are known as Caraquenians in English . It is located in the northern part of the country, following the contours of the narrow Caracas Valley on the Venezuelan coastal mountain range...

and Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires is the capital and largest city of Argentina, and the second-largest metropolitan area in South America, after São Paulo. It is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the southeastern coast of the South American continent...

juntas declared their independence from the Bonapartist government in Spain and sent ambassadors to the United Kingdom. The British blockade

Blockade

A blockade is an effort to cut off food, supplies, war material or communications from a particular area by force, either in part or totally. A blockade should not be confused with an embargo or sanctions, which are legal barriers to trade, and is distinct from a siege in that a blockade is usually...

against Spain had also moved most of the Latin American colonies out of the Spanish economic sphere and into the British sphere, with whom extensive trade relations were developed. The remaining Spanish colonies had operated with virtual independence from Madrid after their pronouncement against Joseph Bonaparte.

The Spanish government in exile (Cádiz Cortes

Cádiz Cortes

The Cádiz Cortes were sessions of the national legislative body which met in the safe haven of Cádiz during the French occupation of Spain during the Napoleonic Wars...

) created the first modern Spanish constitution

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 was promulgated 19 March 1812 by the Cádiz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain, while in refuge from the Peninsular War...

. Even so, agreements made at the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

(where Spain was represented by Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador

Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador

Don Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador was a Spanish diplomat and nobleman who served as Spain's representative at the Congress of Vienna . Labrador did not successfully advance his country's diplomatic goals at the conference...

) would cement international support for the old, absolutist

Absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy is a monarchical form of government in which the monarch exercises ultimate governing authority as head of state and head of government, his or her power not being limited by a constitution or by the law. An absolute monarch thus wields unrestricted political power over the...

regime in Spain.

King Ferdinand VII, who assumed the throne after Napoleon was driven out of Spain, refused to agree to the liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

Spanish Constitution of 1812

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 was promulgated 19 March 1812 by the Cádiz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain, while in refuge from the Peninsular War...

on his accession to the throne in 1814. The Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

in the New World had largely supported the cause of Ferdinand VII over the Bonapartist pretender to the throne in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

. When Ferdinand's rule was restored, these juntas were cautious of abandoning their autonomy, and an alliance between local elites, merchant interests, nationalists, and liberals opposed to the abrogation of the Constitution of 1812 rose up against the Spanish in the New World.

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte y Yeiter, commonly known as Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military and political leader...

, the leader of revolutionary forces in New Granada

Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada was the name given on 27 May 1717, to a Spanish colonial jurisdiction in northern South America, corresponding mainly to modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela. The territory corresponding to Panama was incorporated later in 1739...

, was briefly forced into exile in British-controlled Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

, and independent Haiti

Haiti

Haiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

. In 1816, however, Bolivar found enough popular support that he was able to return to South America, and in a daring march from Venezuela to New Granada (Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

), he defeated Spanish forces at the Battle of Boyacá

Battle of Boyacá

The Battle of Boyacá in Colombia, then known as New Granada, was the battle in which Colombia acquired its definitive independence from Spanish Monarchy, although fighting with royalist forces would continue for years....

in 1819, ending Spanish rule in Colombia. Venezuela

Venezuela

Venezuela , officially called the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela , is a tropical country on the northern coast of South America. It borders Colombia to the west, Guyana to the east, and Brazil to the south...

was liberated June 24, 1821 when Bolivar destroyed the Spanish army on the fields of Carabobo on the Battle of Carabobo. Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

declared its independence in 1816 (though it had been operating with virtual independence as a British client since 1807 after successfully resisting a British invasion). Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

was retaken by Spain in 1814, but lost permanently in 1817 when an army under José de San Martín

José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín, known simply as Don José de San Martín , was an Argentine general and the prime leader of the southern part of South America's successful struggle for independence from Spain.Born in Yapeyú, Corrientes , he left his mother country at the...

, for the first time in history, crossed the Andes Mountains from Argentina to Chile, and went on to defeat Spanish royalist forces at the Battle of Chacabuco

Battle of Chacabuco

The Battle of Chacabuco, fought during the Chilean War of Independence, occurred on February 12, 1817. The Army of the Andes of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata led by General Captain José de San Martín defeated the Spanish force led by Rafael Maroto...

in 1817.

Spain would also lose Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

to the United States during this decade. First, in 1810, the Republic of West Florida

West Florida

West Florida was a region on the north shore of the Gulf of Mexico, which underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. West Florida was first established in 1763 by the British government; as its name suggests it largely consisted of the western portion of the region...

declared its independence from Spain, and was quickly annexed by the United States. Later, in 1818, the United States invaded Florida, resulting in the Adams-Onís Treaty

Adams-Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty or the Purchase of Florida, was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that gave Florida to the U.S. and set out a boundary between the U.S. and New Spain . It settled a standing border dispute between the two...

, wherein Spain ceded the rest of Florida to the United States.

In 1820, Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

, Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

, and Central America

Central America

Central America is the central geographic region of the Americas. It is the southernmost, isthmian portion of the North American continent, which connects with South America on the southeast. When considered part of the unified continental model, it is considered a subcontinent...

still remained under Spanish control. Although Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

had been in revolt in 1811 under Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, resistance to Spanish rule had largely been confined to small guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

bands in the countryside. King Ferdinand was still dissatisfied with the loss of so much of the Empire and resolved to retake it. A large expedition was assembled in Cadiz

Cádiz

Cadiz is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the homonymous province, one of eight which make up the autonomous community of Andalusia....

with the aim of reconquest. However, Ferdinand's plans would be disrupted by Liberal Revolution, and Ferdinand was eventually forced to give up all of the New World colonies, except for Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

.

War of 1812

In 1812, the United States declared war on BritainUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

in the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

. The U.S. reasons for war included the humiliation in the "Chesapeake incident" of 1807

Chesapeake–Leopard Affair

The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair was a naval engagement which occurred off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia on June 22, 1807, between the British warship HMS Leopard and the American frigate, the USS Chesapeake, when the crew of the Leopard pursued, attacked and boarded the American frigate looking for...

, continued British impressment

Impressment

Impressment, colloquially, "the Press", was the act of taking men into a navy by force and without notice. It was used by the Royal Navy, beginning in 1664 and during the 18th and early 19th centuries, in wartime, as a means of crewing warships, although legal sanction for the practice goes back to...

of American sailors into the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

, restrictions on trade with France, and arming hostile American Indians in Ohio and the western territories. United States President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

signed a declaration of war on June 18, 1812.

The United States conducted two failed invasion attempts in 1812, first by General William Hull

William Hull

William Hull was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the American Revolution, was Governor of Michigan Territory, and was a general in the War of 1812, for which he is best remembered for surrendering Fort Detroit to the British.- Early life and Revolutionary War :He was born in...

across the Detroit River

Detroit River

The Detroit River is a strait in the Great Lakes system. The name comes from the French Rivière du Détroit, which translates literally as "River of the Strait". The Detroit River has served an important role in the history of Detroit and is one of the busiest waterways in the world. The river...

into what is now Windsor, Ontario

Windsor, Ontario

Windsor is the southernmost city in Canada and is located in Southwestern Ontario at the western end of the heavily populated Quebec City – Windsor Corridor. It is within Essex County, Ontario, although administratively separated from the county government. Separated by the Detroit River, Windsor...

, and a second offensive at the Niagara peninsula

Niagara Peninsula

The Niagara Peninsula is the portion of Southern Ontario, Canada lying between the south shore of Lake Ontario and the north shore of Lake Erie. It stretches from the Niagara River in the east to Hamilton, Ontario in the west. The population of the peninsula is roughly 1,000,000 people...

. A major American success came in 1813, when the American Navy destroyed the British fleet on Lake Erie, and forced the British and their American Indian allies to retreat back toward Niagara. They were intercepted and destroyed by General William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States , an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. He was 68 years, 23 days old when elected, the oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the...

at the Battle of the Thames

Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames, also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was a decisive American victory in the War of 1812. It took place on October 5, 1813, near present-day Chatham, Ontario in Upper Canada...

in October 1813. Tecumseh

Tecumseh

Tecumseh was a Native American leader of the Shawnee and a large tribal confederacy which opposed the United States during Tecumseh's War and the War of 1812...

, the leader of the tribal confederation, was killed, and his Indian coalition disintegrated.

At sea, the powerful Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

blockaded much of the coastline, conducting frequent raids. The most famous episode was a series of British raids on the shores of Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

, including an attack on Washington that resulted in the British burning of the White House

White House

The White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

, the Capitol

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol is the meeting place of the United States Congress, the legislature of the federal government of the United States. Located in Washington, D.C., it sits atop Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall...

, the Navy Yard

Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy...

, and other public buildings, in the "Burning of Washington

Burning of Washington

The Burning of Washington was an armed conflict during the War of 1812 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States of America. On August 24, 1814, led by General Robert Ross, a British force occupied Washington, D.C. and set fire to many public buildings following...

" in 1814.

Once Napoleon was defeated in 1814, France and Britain became allies and Britain ended the trade restrictions and the impressment of American sailors. Running out of reasons for war and stuck in a military stalemate, the two countries signed the Treaty of Ghent

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent , signed on 24 December 1814, in Ghent , was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

on December 24, 1814. News of the peace treaty took two months to reach the U.S., during which fighting continued. In this interim, the British made one last major invasion, attempting to capture New Orleans, but were decisively defeated with very heavy losses by General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans

Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans took place on January 8, 1815 and was the final major battle of the War of 1812. American forces, commanded by Major General Andrew Jackson, defeated an invading British Army intent on seizing New Orleans and the vast territory the United States had acquired with the...

in January 1815. The ending of the war opened a long era of peaceful relations between the United States and the British Empire.

1804–1813 Russo-Persian War

The 1804–1813 Russo-Persian War was one of the many wars between the Persian EmpireQajar dynasty

The Qajar dynasty was an Iranian royal family of Turkic descent who ruled Persia from 1785 to 1925....

and Imperial Russia, and was well underway at the beginning of the decade. In 1810, the Persians scaled up their efforts late in the war, declaring a holy war on Imperial Russia. However, Russia's superior technology and tactics ensured a series of strategic victories. Even when the French were in occupation of the Russian capital Moscow, Russian forces in the south were not recalled but continued their offensive against Persia, culminating in Pyotr Kotlyarevsky

Pyotr Kotlyarevsky

Pyotr Stepanovich Kotlyarevsky was a Russian military hero of the early 19th century.-Biography:He was born in the village of Olkhovatka near Kharkov into a cleric's family. Kotlyarevsky was brought up in an infantry regiment quartered near Mozdok...

's victories at Aslanduz

Battle of Aslanduz

The Battle of Aslanduz occurred on October 31, 1812, between Russia and Persia. The 10-times numerically superior Persians were led by Abbas Mirza. The Russians, led by the charismatic General Pyotr Kotlyarevsky, were victorious and stormed Lenkoran in the beginning of 1813, thus ending any Persian...

and Lenkoran, in 1812 and 1813 respectively. Upon the Persian surrender, the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan ceded the vast majority of the previously disputed territories to Imperial Russia. This led to the region's once-powerful khans

Khan (title)

Khan is an originally Altaic and subsequently Central Asian title for a sovereign or military ruler, widely used by medieval nomadic Turko-Mongol tribes living to the north of China. 'Khan' is also seen as a title in the Xianbei confederation for their chief between 283 and 289...

being decimated and forced to pay homage to Russia.

Concert of Europe

By 1815, Europe had been almost constantly at war. During this time, the military conquests of France had resulted in the spread of liberalismLiberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

throughout much of the continent, resulting in many states adopting the Napoleonic code

Napoleonic code

The Napoleonic Code — or Code Napoléon — is the French civil code, established under Napoléon I in 1804. The code forbade privileges based on birth, allowed freedom of religion, and specified that government jobs go to the most qualified...

. Largely as a reaction to the radicalism of the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

, the victorious powers of the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

resolved to suppress liberalism and nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, and revert largely to the status quo

Status quo

Statu quo, a commonly used form of the original Latin "statu quo" – literally "the state in which" – is a Latin term meaning the current or existing state of affairs. To maintain the status quo is to keep the things the way they presently are...

of Europe prior to 1789.

Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe , also known as the Congress System after the Congress of Vienna, was the balance of power that existed in Europe from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to the outbreak of World War I , albeit with major alterations after the revolutions of 1848...

, also known as the "Congress System". It was the balance of power

Balance of power in international relations

In international relations, a balance of power exists when there is parity or stability between competing forces. The concept describes a state of affairs in the international system and explains the behavior of states in that system...

that existed in Europe from 1815 until the early 20th century. Its founding members were the United Kingdom

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

, Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

, Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

and Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, the members of the Quadruple Alliance

Quadruple Alliance

The term "Quadruple Alliance" refers to several historical military alliances; none of which remain in effect.# The Quadruple Alliance of August 1673 was an alliance between the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Spain, Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine, and the United Provinces of the Netherlands, in...

responsible for the downfall of the First French Empire

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

; in time France became established as a fifth member of the concert. At first, the leading personalities of the system were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, KG, GCH, PC, PC , usually known as Lord CastlereaghThe name Castlereagh derives from the baronies of Castlereagh and Ards, in which the manors of Newtownards and Comber were located...

, Austrian chancellor Klemens Wenzel, Prince von Metternich and Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

Alexander I

Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I of Russia , served as Emperor of Russia from 23 March 1801 to 1 December 1825 and the first Russian King of Poland from 1815 to 1825. He was also the first Russian Grand Duke of Finland and Lithuania....

of Russia.

The Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

and Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

formed the Holy Alliance

Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance was a coalition of Russia, Austria and Prussia created in 1815 at the behest of Czar Alexander I of Russia, signed by the three powers in Paris on September 26, 1815, in the Congress of Vienna after the defeat of Napoleon.Ostensibly it was to instill the Christian values of...

with the expressed intent of preserving Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

social values and traditional monarchism

Monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the establishment, preservation, or restoration of a monarchy as a form of government in a nation. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government out of principle, independent from the person, the Monarch.In this system, the Monarch may be the...

. Every member of the coalition promptly joined the Alliance, save for the United Kingdom

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

.

Among the meetings of the Powers in the latter part of the 1810s were the Congresses of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

(1814–1815), Aix-la-Chappelle

Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818)

The Congress or Conference of Aix-la-Chapelle , held in the autumn of 1818, was primarily a meeting of the four allied powers Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia to decide the question of the withdrawal of the army of occupation from France and the nature of the modifications to be introduced in...

(1818), and Carlsbad

Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town of Carlsbad, Bohemia...

(1819).

Asia

- 1810: Ching ShihChing ShihChing Shih , also known as Zheng Yi Sao , was a prominent female pirate in middle Qing China.Ching Shih also known as Cheng I Sao terrorized the China Sea in the early 19th century. A brilliant cantonese female pirate, she commanded 1800 ships and more than 80,000 pirates — men, women, and even...

and Chang Pao surrender their pirate fleet to the Chinese government. - 1810: Russia acquires SukhumiSukhumiSukhumi is the capital of Abkhazia, a disputed region on the Black Sea coast. The city suffered heavily during the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict in the early 1990s.-Naming:...

through a treaty with the AbkhaziaAbkhaziaAbkhazia is a disputed political entity on the eastern coast of the Black Sea and the south-western flank of the Caucasus.Abkhazia considers itself an independent state, called the Republic of Abkhazia or Apsny...

n dukes, and declares a protectorateProtectorateIn history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

over the whole of AbkhaziaAbkhaziaAbkhazia is a disputed political entity on the eastern coast of the Black Sea and the south-western flank of the Caucasus.Abkhazia considers itself an independent state, called the Republic of Abkhazia or Apsny...

. - Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812)

- May 28, 1812 – Russian Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov signs the Treaty of BucharestTreaty of Bucharest, 1812The Treaty of Bucharest between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, was signed on 28 May 1812, in Bucharest, at the end of the Russo-Turkish War, 1806-1812....

, ending the Russo-Turkish War, 1806–1812 and making BessarabiaBessarabiaBessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

a part of Imperial Russia.

- May 28, 1812 – Russian Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov signs the Treaty of Bucharest

- October 31, 1817 – Emperor NinkōEmperor Ninkowas the 120th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Ninkō's reign spanned the years from 1817 through 1846.-Genealogy:Before Ninkō's ascension to the Chrysanthemum Throne, his personal name was ....

accedes to the throne of Japan. - 1818: The Third Anglo-Maratha WarThird Anglo-Maratha WarThe Third Anglo-Maratha War was the final and decisive conflict between the British East India Company and the Maratha Empire in India. The war left the Company in control of most of India. It began with an invasion of Maratha territory by 110,400 British East India Company troops, the largest...

is fought between the Marathas and the British East India CompanyBritish East India CompanyThe East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

troops resulting in the defeat of the PeshwaPeshwaA Peshwa is the titular equivalent of a modern Prime Minister. Emporer Shivaji created the Peshwa designation in order to more effectively delegate administrative duties during the growth of the Maratha Empire. Prior to 1749, Peshwas held office for 8-9 years and controlled the Maratha army...

, the breakup of the Maratha EmpireMaratha EmpireThe Maratha Empire or the Maratha Confederacy was an Indian imperial power that existed from 1674 to 1818. At its peak, the empire covered much of South Asia, encompassing a territory of over 2.8 million km²....

, and the loss of Maratha independence to the British as they annexed Central India. The last Peshwa is exiled to Bithur near Kanpur. His adopted son and heir Nana Saheb was one of the principal revolutionary commanders in the Indian Mutiny.

Europe

- August 21, 1810 – Jean-Baptiste BernadotteCharles XIV John of SwedenCharles XIV & III John, also Carl John, Swedish and Norwegian: Karl Johan was King of Sweden and King of Norway from 1818 until his death...

, Marshal of FranceMarshal of FranceThe Marshal of France is a military distinction in contemporary France, not a military rank. It is granted to generals for exceptional achievements...

, is elected Crown PrinceCrown PrinceA crown prince or crown princess is the heir or heiress apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The wife of a crown prince is also titled crown princess....

of Sweden by the Swedish Riksdag of the EstatesRiksdag of the EstatesThe Riksdag of the Estates , was the name used for the Estates of the Swedish realm when they were assembled. Until its dissolution in 1866, the institution was the highest authority in Sweden next to the King...

. - September 26, 1810 – A new Act of SuccessionSwedish Act of SuccessionThe Act of Succession is a part of the Swedish Constitution. It was adopted by the Riksdag of the Estates on September 26, 1810, and it regulates the right of members of the House of Bernadotte to accede to the Swedish throne...

is adopted by the Riksdag of the EstatesRiksdag of the EstatesThe Riksdag of the Estates , was the name used for the Estates of the Swedish realm when they were assembled. Until its dissolution in 1866, the institution was the highest authority in Sweden next to the King...

and Jean Baptiste Bernadotte becomes heir to the SwedishSwedenSweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

throne. - October 12, 1810 – First OktoberfestOktoberfestOktoberfest, or Wiesn, is a 16–18 day beer festival held annually in Munich, Bavaria, Germany, running from late September to the first weekend in October. It is one of the most famous events in Germany and is the world's largest fair, with more than 5 million people attending every year. The...

: The BavariaBavariaBavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

n royalty invites the citizens of MunichMunichMunich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

to join the celebration of the marriage of Crown Prince Ludwig of BavariaLudwig I of BavariaLudwig I was a German king of Bavaria from 1825 until the 1848 revolutions in the German states.-Crown prince:...

to PrincessPrincessPrincess is the feminine form of prince . Most often, the term has been used for the consort of a prince, or his daughters....

Therese of Saxe-HildburghausenTherese of Saxe-HildburghausenTherese Charlotte Luise of Saxony-Hildburghausen was a queen of Bavaria.She was a daughter of Frederick, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg, and Duchess Charlotte Georgine of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, eldest daughter of Charles II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.-Biography:In 1809, she was on the list of...

. - February 5, 1811 – British Regency: George, Prince of WalesGeorge IV of the United KingdomGeorge IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

becomes Prince RegentPrince RegentA prince regent is a prince who rules a monarchy as regent instead of a monarch, e.g., due to the Sovereign's incapacity or absence ....

because of the perceived insanity of his father, King George III of the United KingdomGeorge III of the United KingdomGeorge III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

. - September, 1811 – Nathan of BreslovNathan of BreslovNathan of Breslov , also known as Reb Noson, born Nathan Sternhartz, was the chief disciple and scribe of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, founder of the Breslov Hasidic dynasty. Reb Noson is credited with preserving, promoting and expanding the Breslov movement after the Rebbe's death...

leads the first annual Rosh Hashana kibbutzRosh Hashana kibbutz (Breslov)The Rosh Hashana kibbutz is a large prayer assemblage of Breslover Hasidim held on the Jewish New Year. It specifically refers to the pilgrimage of tens of thousands of Hasidim to the city of Uman, Ukraine, but also refers to sizable Rosh Hashana gatherings of Breslover Hasidim in other locales...

(pilgrimage) of BreslovBreslov (Hasidic dynasty)Breslov is a branch of Hasidic Judaism founded by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov a great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism...

Hasidim to the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov in Uman, Ukraine. - January 1, 1812 – The Allgemeines bürgerliches GesetzbuchAllgemeines bürgerliches GesetzbuchThe Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch is the Civil Code of Austria, which was enacted in 1811 after about 40 years of preparatory works. Karl Anton Freiherr von Martini and Franz von Zeiller were the leading drafters at the earlier and later stages of the draft. Comparable to the Napoleonic...

(the Austrian civil codeCivil codeA civil code is a systematic collection of laws designed to comprehensively deal with the core areas of private law. A jurisdiction that has a civil code generally also has a code of civil procedure...

) enters into force in the Austrian EmpireAustrian EmpireThe Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

. - May 11, 1812 – John BellinghamJohn BellinghamJohn Bellingham was the assassin of British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval. This murder was the only successful attempt on the life of a British Prime Minister...

assassinates BritishUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and IrelandThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

Prime MinisterPrime ministerA prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

Spencer PercevalSpencer PercevalSpencer Perceval, KC was a British statesman and First Lord of the Treasury, making him de facto Prime Minister. He is the only British Prime Minister to have been assassinated...

in the lobby of the British House of CommonsBritish House of CommonsThe House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

. - July 18, 1812 – Russia's Patriotic War, 1812 – Battle of KlyastitsyBattle of KlyastitsyThe Battle of Klyastitsy, also called battle of Yakubovo, refers to a series of military engagements, which took place in 1812 near the village of Klyastitsy on the road between Polotsk and Sebezh. In this battle the Russian corps under the command of Peter Wittgenstein, stood up to the French...

: Kulnev defeats Oudinot but sustains a mortal wound. - October 18–October 20, 1812 – Second Battle of PolotskSecond Battle of PolotskThe Second Battle of Polotsk took place during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. In this encounter the Russians under General Peter Wittgenstein attacked and defeated a Franco-Bavarian force under Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr. In the aftermath of this success, the Russians took Polotsk and dismantled...

– Russia - December 30, 1812 – Convention of TauroggenConvention of TauroggenThe Convention of Tauroggen was a truce signed 30 December 1812 at Tauroggen , between Generalleutnant Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg on behalf of his Prussian troops, and by General Hans Karl von Diebitsch of the Russian Army...

was signed. - 1812 – The capital of Finland is moved from TurkuTurkuTurku is a city situated on the southwest coast of Finland at the mouth of the Aura River. It is located in the region of Finland Proper. It is believed that Turku came into existence during the end of the 13th century which makes it the oldest city in Finland...

to HelsinkiHelsinkiHelsinki is the capital and largest city in Finland. It is in the region of Uusimaa, located in southern Finland, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, an arm of the Baltic Sea. The population of the city of Helsinki is , making it by far the most populous municipality in Finland. Helsinki is...

. - November 10, 1813 – A general electionUnited Kingdom general election, 1812The election to the 5th Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1812 was the fourth general election to be held after the Union of Great Britain and Ireland....

in the United Kingdom sees victory for the ToryToryToryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

Party under Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of LiverpoolRobert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of LiverpoolRobert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool KG PC was a British politician and the longest-serving Prime Minister of the United Kingdom since the Union with Ireland in 1801. He was 42 years old when he became premier in 1812 which made him younger than all of his successors to date...

. - 1813 – George Hamilton-Gordon serves as ambassador extraordinaire in ViennaViennaVienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

. - 1813 – Following the death of his father Wossen SegedWossen SegedWossen Seged was a Meridazmach of Shewa, an important Prince of Ethiopia. He was the elder son of Asfa Wossen, by a woman of the Solomonic dynasty. He was the first ruler of Shewa to claim a higher title than Meridazmach, calling himself Ras.It is during the reign of Wossen Seged that the...

, Sahle SelassieSahle SelassieSahle Selassie was a Meridazmach of Shewa , an important noble of Ethiopia. He was a younger son of Wossen Seged...

arrives at the capital Qundi before his other brothers, and is made Méridazmach of ShewaShewaShewa is a historical region of Ethiopia, formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire...

. - Norway in 1814Norway in 18141814 was a pivotal year in the history of Norway. It started with Norway in a union with the Kingdom of Denmark subject to a naval blockade being ceded to the king of Sweden. In May a constitutional convention declared Norway an independent kingdom. By the end of the year the Norwegian parliament...

- January 14, 1814 – Denmark cedes Norway to Sweden in exchange for west PomeraniaPomeraniaPomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

, as part of the Treaty of KielTreaty of KielThe Treaty of Kiel or Peace of Kiel was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 in Kiel...

. - February 11, 1814 – Norway's independence is proclaimed, marking the ultimate end of the Kalmar UnionKalmar UnionThe Kalmar Union is a historiographical term meaning a series of personal unions that united the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway , and Sweden under a single monarch, though intermittently and with a population...

. - April 12, 1814 – The Royal Norwegian NavyRoyal Norwegian NavyThe Royal Norwegian Navy is the branch of the Norwegian Defence Force responsible for naval operations. , the RNoN consists of approximately 3,700 personnel and 70 vessels, including 5 heavy frigates, 6 submarines, 14 patrol boats, 4 minesweepers, 4 minehunters, 1 mine detection vessel, 4 support...

is re-established. - May 17, 1814 – The Constitution of NorwayConstitution of NorwayThe Constitution of Norway was first adopted on May 16, 1814 by the Norwegian Constituent Assembly at Eidsvoll , then signed and dated May 17...

is signed and the DanishDenmarkDenmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

Crown PrinceCrown PrinceA crown prince or crown princess is the heir or heiress apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The wife of a crown prince is also titled crown princess....